A King’s Noble Vision: ‘Iolani Palace in an Age of Historical Recovery

1

There are certain standards that need to be met with regard to the terms “indigenous sovereignty” and “state sovereignty” and it begins with definitions. The former applies to indigenous peoples, while the latter applies to independent States. Current usage in Hawaiian discourse tends to conflate the two terms as if they are synonymous. This is a grave mistake that only adds to the already confusing discourse of sovereignty talk amongst Hawai‘i’s population. Instead of beginning with the definition of the terms and their difference, there is a tendency to argue native Hawaiians are an indigenous people as if it is a forgone conclusion.

Indigenous studies make a clear distinction between the terms. Corntassel and Primeau’s article “Indigenous ‘Sovereignty’ and International Law: Revised Strategies for Pursuing ‘Self-Determination,” Human Rights Quarterly 17.2 (1995) 343-365), refers to indigenous people as a “stateless group in the international system.” Defining a stateless group, Corntassel and Primeau cite Milton J. Esman’s article, “Ethnic Pluralism and International Relations,” Canadian Review of Studies in Nationalism 27 (1990): 88, where he defines non-state nations as ethnic groups that do not have a patron State of their own.

While the State has its origins that date back to 1648—Treaty of Westphalia, it wasn’t until 1982 that the United Nations officially recognized indigenous groups when it formed the UN Working Group on Indigenous Populations. That year the Working Group came up with its definition of indigenous populations. “Indigenous populations are composed of the existing descendants of the peoples who inhabited the present territory of a country wholly or partially at the time when persons of a different culture or ethnic origin arrived there from other parts of the world, overcame them, and, by conquest, settlement or other means reduced them to a non-dominant or colonial condition; who today live more in conformity with the particular social, economic and cultural customs and traditions that with the institutions of the country of which they now form part, under a State structure which incorporates mainly the national, social and cultural characteristics of other segments of the population which are predominant.”

According to Corntassel and Primeau the Working Group’s definition was so broad that “any non-state nation … could fit under the term ‘indigenous population (p. 347),’” which would go outside the Working Group’s focus on tribal populations. They argue that under such a broad definition any people that are non-States such as Basques, Kurds, Abkazians, Bretons, Chechens, Tibetans, Timorese, Puerto Ricans, Northern Irish, Welsh, Tamils, Madan Arabs, or Palestinians could identify themselves as “indigenous people (p. 348).”

Seven years later, in a move to limit the definition to tribes, the term “tribal peoples” was inserted in Article 1 of the 1989 Convention concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries, No. 169, adopted by the International Labor Organization. Article 1, provides: “(a) tribal peoples in independent countries [States] whose social, cultural and economic conditions distinguish them from other sections of the national community, and whose status is regulated wholly or partially by their own customs or traditions or by special laws or regulations; (b) peoples in independent countries [States] who are regarded as indigenous on account of their descent from the populations which inhabited the country, or a geographical region to which the country belongs, at the time of conquest or colonisation or the establishment of present state boundaries and who, irrespective of their legal status, retain some or all of their own social, economic, cultural and political institutions.”

An “independent country” is an independent State that is a self-governing entity possessing absolute and independent legal and political authority over its territory to the exclusion of other States. All members of the United Nations are independent States. The ILO was clearly distinguishing between indigenous tribal peoples and the States they reside in. The 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples also makes that distinction in Articles 5, 8(2), 11(2), 12(2), 13(2), 14(2) (3), 15(2), 16(2), 17(2), 19, 21(2), 22(2), 24(2), 26(3), 27, 29, 30(1) (2), 32(2) (3), 33(1), 36(2), 37(1), 38, 39, 40, 42, and 46(1).

The ILO Convention covered the “what” are indigenous populations, being “tribal peoples in independent countries [States],” but it did not satisfactorily determine the “who.” This was somewhat addressed by Jose R. Martinez Cobo, Special Rapporteur of the Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities, in his 1986 Report on the Study on the Problem of Discrimination against Indigenous Populations, which stated:

“Indigenous communities, peoples and nations are those which, having a historical continuity with pre-invasion and pre-colonial societies that developed on their territories, consider themselves distinct from other sectors of the societies now prevailing on those territories, or parts of them. They form at present non-dominant sectors of society and are determined to preserve, develop and transmit to future generations their ancestral territories, and their ethnic identity, as the basis of their continued existence as peoples, in accordance with their own cultural patterns, social institutions and legal system (paragraph 379).”

“This historical continuity may consist of the continuation, for an extended period reaching into the present of one or more of the following factors: (a) Occupation of ancestral lands, or at least of part of them; (b) Common ancestry with the original occupants of these lands; (c) Culture in general, or in specific manifestations (such as religion, living under a tribal system, membership of an indigenous community, dress, means of livelihood, lifestyle, etc.); (e) Language (whether used as the only language, as mother-tongue, as the habitual means of communication at home or in the family, or as the main, preferred, habitual, general or normal language); (f) Residence on certain parts of the country, or in certain regions of the world; (g) Other relevant factors (paragraph 380).”

“On an individual basis, an indigenous person is one who belongs to these indigenous populations through self-identification as indigenous (group consciousness) and is recognized and accepted by these populations as one of its members (acceptance by the group) (paragraph 381).”

Throughout his report, Cobo also distinguishes between indigenous populations and the States they reside. On this note, Cobo recommends:

“States should seek to gear their policies to the wish of indigenous populations to be considered different, as well as to the ethnic identity explicitly defined by such populations. In the view of the Special Rapporteur, this should be done within a context of socio-cultural and political pluralism which affords such populations the necessary degree of autonomy, self-determination and self-management commensurate with the concepts of ethnic development (paragraph 400).”

“Countries with indigenous populations should review periodically their administrative measures for the formulation and implementation of indigenous population policy, taking particular account of the changing needs of such communities, their points of view and the administrative approaches which have met with success in countries where similar situations obtain (paragraph 404).”

In the 1996 Report of the Working Group (paragraph 31), representatives of the indigenous populations stated, “We, the Indigenous Peoples present at the Indigenous Peoples Preparatory Meeting on Saturday, 27 July 1996, at the World Council of Churches, have reached a consensus on the issue of defining Indigenous Peoples and have unanimously endorsed Sub-Commission resolution 1995/32. We categorically reject any attempts that Governments define Indigenous Peoples. We further endorse the Martinez Cobo report (E/CN.4/Sub.2/1986/Add.4) in regard to the concept of “indigenous.” The 2007 Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples does not provide for a different definition of indigenous peoples, but rather declares their rights within the States they reside.

In 2001, the Permanent Court of Arbitration, in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, concluded, that “in the nineteenth century the Hawaiian Kingdom existed as an independent State recognized as such by the United States of America, the United Kingdom and various other States, including by exchanges of diplomatic or consular representatives and the conclusion of treaties.” There are no indigenous people in the Hawaiian Islands because the aboriginal Hawaiians formed the State themselves, comparable to other Polynesians who formed their own States such as Samoa in 1962, and Tonga in 1970. Both States are members of the United Nations. The only difference, however, was that Hawai‘i was the first of the Polynesians to be recognized as an independent State. Furthermore, Samoans and Tongans do not refer to themselves as an “indigenous people,” but rather the citizenry of two independent States.

This is why it is paradoxical to say that natives of Hawai‘i (kanaka) are an indigenous people because it would imply they do not have a State of their own. This labeling of Hawaiian natives as indigenous people is an American narrative that has no basis in historical facts or law other than people just saying it. Rather, natives are the majority of Hawaiian subjects, being the citizenry of the Hawaiian Kingdom that has been in an unjust war by the United States since 1893.

There has been some confusion as to who, in particular, determines whether a state of war exists for international law purposes. Is it a decision made by army commanders, international courts, or the heads of state? To answer this question we first need to understand the term war. By definition, war is a violent contention between two or more countries, called States, which is allowable under international law.

War as it is understood today is different from what it was understood in the nineteenth century when the Hawaiian Kingdom government was unlawfully overthrown by United States armed forces on January 17, 1893. According to Professor Brownlie, “The right of war, as an aspect of sovereignty, which existed in the period before 1914, subject to the doctrine that war was a means of last resort in the enforcement of legal rights, was very rarely asserted either by statesmen or works of authority without some stereotyped plea to a right of self-preservation, and of self-defence, or to necessity or protection of vital interests, or merely alleged injury to rights or national honour and dignity.” (Ian Brownlie, International Law and the Use of Force by States (1963) 41).

In the absence of a system of dispute resolution, such as today’s Permanent Court of Arbitration (est. 1899) or the International Court of Justice (est. 1945), war was seen as a form of judicial procedure, a litigation of sorts between nations that involved lethal punishment. It was a means by which one State could obtain redress for wrongs committed against it. War, however, was considered a course of last resort.

“It was generally thought that a state of war came into existence between two countries if, and only if, one of these countries made it clear that it regarded itself as being in a state of war,” says Judge Greenwood. (Christopher Greenwood, “Scope of Application of Humanitarian Law,” in Dieter Fleck (ed), The Handbook of the International Law of Military Operations (2nd ed., 2008) 45). Representatives of countries in international law are Heads of Governments, whether they are Presidents, Monarchs or Prime Ministers. Any political determination made by these Heads of States that their countries are in a state of war is conclusive. In the case of the United States it would be the President, and in the case of the Hawaiian Kingdom it would be the Monarch.

International law differentiates a “declaration of war” from a “state of war.” According to McNair and Watts, “the absence of a declaration…will not of itself render the ensuing conflict any less a war.” In other words, since a state of war is based upon concrete facts of military action there is no requirement for a formal declaration of war to be made. In 1946, a United States Federal Court had to determine whether a United States naval captain’s life insurance policy, which excluded coverage if death came about as a result of war, covered his death during the Japanese attack of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1945. The family of the captain was arguing that the United States was not a war at the time of his death because the Congress did not declare war against Japan until the following day. The Court denied the family’s claim and determined, “that the formal declaration by the Congress on December 8th was not an essential prerequisite to a political determination of the existence of a state of war commencing with the attack on Pearl Harbor.” (New York Life Ins. Co. v. Bennion, 158 F.2d 260 (C.C.A. 10th, 1946), 41 American Journal of International Law (1947), 682).

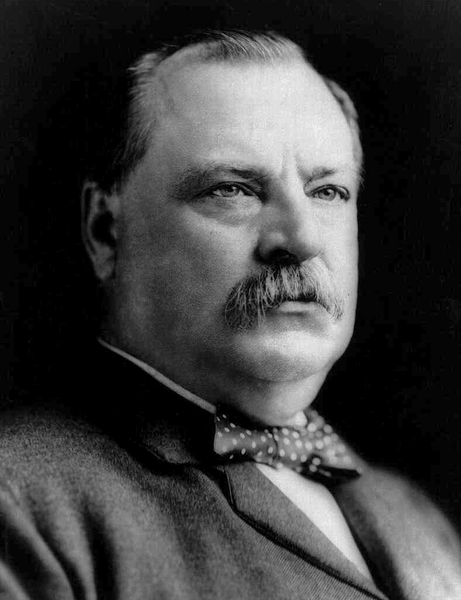

On the 100th anniversary of the United States unlawful overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government in 1893, the United States Congress enacted a joint resolution offering an apology. Of significance in the resolution was a particular “whereas” clause, which stated “Whereas, in a message to Congress on December 18, 1893, President Grover Cleveland reportedly fully and accurately on the illegal acts of the conspirators, described such acts as an ‘act of war, committed with the participation of a diplomatic representative of the United States and without authority of Congress, and acknowledged that by such acts the government of a peaceful and friendly people was overthrown.” (Annexure 2, Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, 119 International Law Reports (2001) 612).

At first read, it would appear that the “conspirators” were the subjects that committed the “act of war,” but this is misleading. First, under international law, only a country can commit an “act of war”, whether through its military and/or its diplomats; and, second, under municipal laws, which are the laws applicable to a particular country, conspirators within a country could only commit treason not “acts of war.” These two concepts are reflected in the terms coup de main and coup d’état. The former is a successful invasion by an outside military force, while the former is a successful internal revolt, which was also referred to in the nineteenth century as a revolution. According to the United States Department of Defense, a coup de main is an “offensive operation that capitalizes on surprise and simultaneous execution of supporting operations to achieve success in one swift stroke.” (U.S. Department of Defense, The Dictionary of Military Terms (2009)).

In a petition to President Cleveland on December 27, 1893, from the Hawaiian Patriotic League, its leadership, comprised of Hawaiian statesmen and lawyers, clearly articulated the difference between a “revolution” and a “coup de main,” and, as such, an international crime was committed. The petition read:

“Last January, a political crime was committed, not only against the legitimate Sovereign of the Hawaiian Kingdom, but also against the whole of the Hawaiian nation, a nation who, for the past sixty years, had enjoyed free and happy constitutional self-government. This was done by a coup de main of U.S. Minister Stevens, in collusion with a cabal of conspirators, mainly faithless sons of missionaries and local politicians angered by continuous political defeat, who, as revenge for being a hopeless minority in the country, resolved to ‘rule or ruin’ through foreign help. The facts of this ‘revolution,’ as it is improperly called, are now a matter of history.” (Petition of the Hawaiian Patriotic League to President Cleveland (Dec. 27, 1893), The Executive Documents of the House of Representatives (1895), 1295).

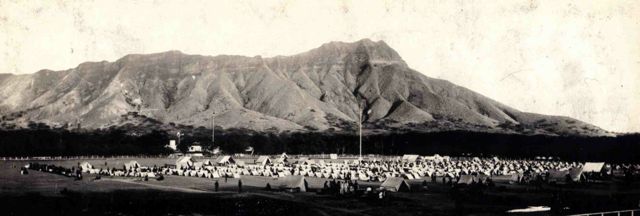

Whether by chance or design, the 1993 Congressional Apology Resolution did not accurately reflect what President Cleveland stated in his message to Congress on December 18, 1893. When Cleveland stated that the “military demonstration upon the soil of Honolulu was of itself an act of war,” he was referring to United States armed forces and not to any of the conspirators. Cleveland noted, “that on the 16th day of January, 1893, between four and five o’clock in the afternoon, a detachment of marines from the United States steamer Boston, with two pieces of artillery, landed at Honolulu. The men, upwards of 160 in all, were supplied with double cartridge belts filled with ammunition and with haversacks and canteens, and were accompanied by a hospital corps with stretchers and medical supplies.” Clearly the act of war was committed by the armed forces of the United States. The landing, however, was just the beginning stage of a coup de main with the ultimate goal of seizing control of the Hawaiian government.

As part of the plan, the U.S. diplomat, John Stevens, would prematurely recognize the small group of insurgents on January 17th as if they were a successful revolution thereby giving it de facto status. International law, however, provides the parameters by which a revolution is deemed to have been successful. Foreign States would acknowledge success when an insurgency has secured complete control of all governmental machinery, no opposition by the lawful government, and has the acquiescence of the national population. According to Professor Lauterpacht, “So long as the revolution has not been successful, and so long as the lawful government…remains within national territory and asserts its authority, it is presumed to represent the State as a whole.” (E. Lauterpacht, Recognition in International Law (1947) 93). With full knowledge of what constitutes a successful revolution, Cleveland provided a blistering indictment:

“When our Minister recognized the provisional government the only basis upon which it rested was the fact that the Committee of Safety…declared it to exist. It was neither a government de facto nor de jure. That it was not in such possession of the Government property and agencies as entitled it to recognition is conclusively proved by a note found in the files of the Legation at Honolulu, addressed by the declared head of the provisional government to Minister Stevens, dated January 17, 1893, in which he acknowledges with expressions of appreciation the Minister’s recognition of the provisional government, and states that it is not yet in the possession of the station house (the place where a large number of the Queen’s troops were quartered), though the same had been demanded of the Queen’s officers in charge.” (Annexure 1—President Cleveland’s message to the Senate and House of Representatives dated 18 December 1893, Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, 119 International Law Reports (2001) 605).

“Premature recognition is a tortious act against the lawful government,” explains Professor Lauterpacht, which “is a breach of international law.” (Ibid, 95). And according to Stowell, a “foreign state which intervenes in support of [insurgents] commits an act of war against the state to which it belongs, and steps outside the law of nations in time of peace.” (Ellery C. Stowell, Intervention in International Law (1921) 349, n. 75). Furthermore Stapleton states, “Of all the principles in the code of international law, the most important—the one which the independent existence of all weaker States must depend—is this: no State has a right FORCIBLY to interfere in the internal concerns of another State.” (Augustus Granville Stapleton, Intervention and Non-Intervention (1866) 6).

Cleveland then explained to the Congress the egregious effects these acts of war had upon the Hawaiian government and its apprehension of a “cabal of conspirators” who committed high treason.

“Nevertheless, this wrongful recognition by our Minister placed the Government of the Queen in a position of most perilous perplexity. On the one hand she had possession of the palace, of the barracks, and of the police station, and had at her command at least five hundred fully armed men and several pieces of artillery. Indeed, the whole military force of her kingdom was on her side and at her disposal, while the Committee of Safety, by actual search, had discovered that there were but very few arms in Honolulu that were not in the service of the Government. In this state of things if the Queen could have dealt with the insurgents alone her course would have been plain and the result unmistakable. But the United States had allied itself with her enemies, had recognized them as the true Government of Hawaii, and had put her and her adherents in the position of opposition against lawful authority. She knew that she could not withstand the power of the United States, but she believed that she might safely trust to its justice. Accordingly, some hours after the recognition of the provisional government by the United States Minister, the palace, the barracks, and the police station, with all the military resources of the country, were delivered up by the Queen upon the representation made to her that her cause would thereafter be reviewed at Washington, and while protesting that she surrendered to the superior force of the United States, whose Minister had caused United States troops to be landed at Honolulu and declared that he would support the provisional government, and that she yielded her authority to prevent collision of armed forces and loss of life and only until such time as the United States, upon the facts being presented to it, should undo the action of its representative and reinstate her in the authority she claimed as the constitutional sovereign of the Hawaiian Islands.” (Annexure 1—President Cleveland’s message to the Senate and House of Representatives dated 18 December 1893, Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, 119 International Law Reports (2001) 606).

According to Professor Wright, “War begins when any state of the world manifests its intention to make war by some overt act, which may take the form of an act of war.” Quincy Wright, “Changes in the Concept of War,” 18 American Journal of International Law (1924) 758). In his review of customary international law in the nineteenth century, Professor Brownlie concluded, “that in so far a ‘state of war’ had any generally accepted meaning it was a situation regarded by one or both parties to a conflict as constituting a ‘state of war.’” (Brownlie, 38).

Cleveland concluded by an “act of war…the Government of a feeble but friendly and confiding people has been overthrown.”(Annexure 1—President Cleveland’s message to the Senate and House of Representatives dated 18 December 1893, Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, 119 International Law Reports (2001) 608). More importantly, Cleveland referred to the Hawaiian people as “friendly and confiding,” not “hostile.” This is a classic case of where the United States President admits an unjust war, but a state of war nevertheless. In the absence of a treaty or agreement to end the state of war that has ensued for over a century, international humanitarian law regulates the Hawaiian situation.

These are the very matters that will come before the International Commission of Inquiry: Incidents of War Crimes in the Hawaiian Islands—The Larsen Case.

As the Tribunal at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom pointed out in, “in the nineteenth century the Hawaiian Kingdom existed as an independent State recognized as such by the United States of America, the United Kingdom and various other States, including by exchanges of diplomatic or consular representatives and the conclusion of treaties.” (Award, Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, 119 International Law Reports (2001) 581). As an independent State, the Hawaiian Kingdom was a member of the Family of Nations along with other independent States including the United States. According to Westlake in 1894, they comprised, “First, all European States […] Secondly, all American States […] Thirdly, a few Christian States in other parts of the world, as the Hawaiian Islands, Liberia and the Orange Free State.” (John Westlake, Chapters on the Principles of International Law (1894) 81).

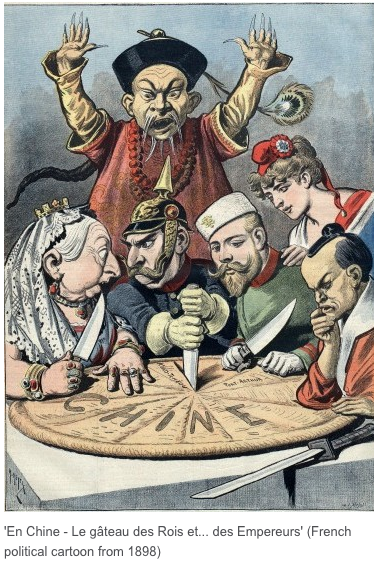

In 1893, there were 44 independent and sovereign States in the Family of Nations: Argentina, Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Bolivia, Brazil, Bulgaria, Chili, Colombia, Costa Rica, Denmark, Ecuador, France, Germany, Great Britain, Greece, Guatemala, Hawaiian Kingdom, Haiti, Honduras, Italy, Liberia, Lichtenstein, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Mexico, Monaco, Montenegro, Nicaragua, Orange Free State that was later annexed by Great Britain in 1900, Paraguay, Peru, Portugal, Romania, Russia, San Domingo, San Salvador, Serbia, Spain, Sweden-Norway, Switzerland, Turkey, United States of America, Uruguay, and Venezuela. In 1945, there were 45, and today there are 193.

From a State of Peace to a State of War—No Middle Ground

International law, which is law between nations, formed the protocol and relations between these member States. “Traditional international law was based upon a rigid distinction between the state of peace and the state of war,” states Judge Greenwood (Christopher Greenwood, “Scope of Application of Humanitarian Law,” in Dieter Fleck (ed), The Handbook of the International Law of Military Operations (2nd ed., 2008) 45). “Countries were either in a state of peace or a state of war; there was no intermediate state.” (Ibid.) This is also reflected by the fact that the renowned jurist of international law, Lassa Oppenheim, separates his treatise on International Law into two volumes, Vol. I—Peace, and Vol. II—War and Neutrality.

Throughout the nineteenth century, the Hawaiian Kingdom was not only independent and sovereign, but also a neutral State explicitly recognized by treaties with Germany, Spain and Sweden-Norway. The Hawaiian Kingdom enjoyed a state of peace with all States. This status of affairs, however, was interrupted by the United States when the state of peace was transformed to a state of war that began on January 16, 1893. On January 17, 1893, Queen Lili‘uokalani, the Executive Monarch of the Hawaiian Kingdom, made the following protest and a conditional yielding of her authority to the President of the United States in response to military action taken against the Hawaiian government by order of the U.S. resident diplomat John Stevens. The Queen’s protest stated:

“I, Liliuokalani, by the grace of God and under the constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Queen, do hereby solemnly protest against any and all acts done against myself and the constitutional Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom by certain persons claiming to have established a provisional government of and for this Kingdom. That I yield to the superior force of the United States of America, whose minister plenipotentiary, His Excellency John L. Stevens, has caused United States troops to be landed at Honolulu and declared that he would support the said provisional government. Now, to avoid any collision of armed forces and perhaps the loss of life, I do, under this protest, and impelled by said force, yield my authority until such time as the Government of the United States shall, upon the facts being presented to it, undo the action of its representatives and reinstate me in the authority which I claim as the constitutional sovereign of the Hawaiian Islands.” (Annexure 2, Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, 119 International Law Reports (2001) 612).

Under international law, the landing of American troops without the consent of the Hawaiian government was an act of war. But in order for an act of war to transform the status of affairs to a state of war, the act must be unlawful under international law. In other words, an act of war would not change the status of affairs to a state of war from that of peace if the action were legal under international law. According to Professor Wright, “An act of war is an invasion of territory…and so normally illegal. Such an act if not followed by war gives grounds for a claim which can be legally avoided only by proof of some special treaty or necessity justifying the act.” (Quincy Wright, “Changes in the Concept of War,” 18 American Journal of International Law (1924), 756).

Military action in a foreign State considered lawful under international law, includes proportionate reprisals in response to another State’s action just short of all out war, and military actions taken to protect its citizenry in the foreign State. Furthermore, the act of war must have been intentional—animo belligerendi, to overthrow the government of the invaded State. As international law is a law between States, which derives from agreements, the claim made by Queen Lili‘uokalani that United States troops unlawfully invaded the kingdom had to be acknowledged by the President of the United States as true. In her protest she called upon the President to investigate the facts and then “undo the action of its representatives and reinstate me in the authority which I claim as the constitutional sovereign of the Hawaiian Islands.” In international law, this is called restitutio in integrum.

After ten months of investigating the overthrow, President Cleveland notified the Congress on December 18, 1893, that the “military demonstration upon the soil of Honolulu was of itself and act of war” that could not be justified under international law as “either with the consent of the Government of Hawaii or for the bona fide purpose of protecting the imperiled lives and property of citizens of the United States.” (Annexure 1—President Cleveland’s message to the Senate and House of Representatives dated 18 December 1893, Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, 119 International Law Reports (2001) 604).

The President then concluded, “By an act of war, committed with the participation of a diplomatic representative of the United States and without authority of Congress, the Government of a feeble but friendly and confiding people has been overthrown.” (Ibid, 608). He notified the Congress that he initiated negotiations with the Queen “to aid in the restoration of the status existing before the lawless landing of the United States forces at Honolulu on the 16th of January last, if such restoration could be effected upon terms providing for clemency as well as justice to all parties concerned.” (Ibid, 610). What Cleveland did not know at the time of his message to the Congress was that the Queen, on the very same day in Honolulu, accepted the conditions for settlement in an attempt to return to a state of peace. The executive mediation began on November 13, 1893 between the Queen and U.S. diplomat Albert Willis. The President was not aware of the agreement until January 12, 1894.

Despite being unaware of the agreement to settle, President Cleveland’s political determination was an acknowledgment that the United States was in a state of war with the Hawaiian Kingdom since the invasion occurred on January 16, 1893, as stated by the Queen in her protest on January 17, 1893. International law defines war as “a contention between States for the purpose of overpowering each other.” (L. Oppenheim, International Law, vol. II—War and Neutrality (3rd ed., 1921) 74).

Once a state of war ensued between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States, “the law of peace ceased to apply between them and their relations with one another became subject to the laws of war, while their relations with other states not party to the conflict became governed by the law of neutrality.” (Greenwood, 45). This outbreak of a state of war between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States would “lead to many rules of the ordinary law of peace being superseded…by rules of humanitarian law.” (Ibid, 46).

A state of war “automatically brings about the full operation of all the rules of war and neutrality.” (Myers S. McDougal, “The Initiation of Coercion: A Multi-temporal Analysis,” 52 American Journal of International Law (1948) 247). And according to Venturini, “If an armed conflict occurs, the law of armed conflict must be applied from the beginning until the end, when the law of peace resumes in full effect.” (Gabriella Venturini, “The Temporal Scope of Application of the Conventions,” in Andrew Clapham, Paola Gaeta, and Marco Sassòli (eds), The 1949 Geneva Conventions: A Commentary (2015), 52). Only by a treaty or agreement between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States could a state of peace be restored, without which a state of war ensues.

In order to transform the state of war to a state of peace an attempt was made by executive agreement entered into between President Cleveland, by his resident diplomat Albert Willis, and Queen Lili‘uokalani in Honolulu on December 18, 1893 (David Keanu Sai, “A Slippery Path Towards Hawaiian Indigeneity: An Analysis and Comparison between Hawaiian State Sovereignty and Hawaiian Indigeneity and Its Use and Practice Today,” 10 Journal of Law and Social Challenges (2008) 119-127). Cleveland, however, was unable to carry out his duties and obligations to restore the situation that existed before the unlawful landing of American troops due to political wrangling in the Congress. The state of war continued.

It is a common misconception that only through a declaration of war by the Congress could a state of war exist for the United States. A Federal court in 1946, however, dispensed with this theory in New York Life Ins. Co. v. Bennion. The Court stated, “it cannot be denied that the acts and conduct of the President, acting in furtherance of his constitutional authority and duty, would constitute a political determination of a state of war of which the courts would take judicial notice. We can discern no demonstrable difference in the supposition and the actual facts, and we therefore conclude that the formal declaration by the Congress on December 8th was not an essential prerequisite to a political determination of the existence of a state of war commencing with the attack on Pearl Harbor [on December 7th].” (New York Life Ins. Co. v. Bennion, 158 F.2d 260 (C.C.A. 10th, 1946), 41 American Journal of International Law (1947), 682).

Therefore, the conclusion reached by President Cleveland that an act of war had been committed by the United States was a “political determination of the existence of a state of war,” and that a formal declaration of war by the Congress was not essential. The “political determination” by President Cleveland regarding the actions taken by the military forces of the United States on January 16, 1893, was the same as the “political determination” by President Roosevelt regarding actions taken by the military forces of Japan on December 7, 1945. Both “political determinations,” being acts of war, created a state of war for the United States. A declaration of war by the Congress was not essential in both situations.

The Duty of Neutrality by Third States

When the President declared that a state of war existed by an act of war committed by the American military in his message to Congress, all of the other 42 States were under a duty of neutrality. “Since neutrality is an attitude of impartiality, it excludes such assistance and succour to one of the belligerents as is detrimental to the other, and, further such injuries to the one as benefit the other.” (L. Oppenheim, International Law, vol. II—War and Neutrality (3rd ed., 1921) 401).

The duty of a neutral State, not a party to the conflict, “obliges him, in the first instance, to prevent with the means at his disposal the belligerent concerned from committing such a violation,” e.g. to deny recognition of a puppet government unlawfully created by an act of war. (Ibid, 496). Twenty of these States violated their obligation of impartiality by recognizing the so-called Republic of Hawai‘i, a United States puppet government created by an act of war committed by the United States on January 17, 1893. These States include:

“If a neutral neglects this obligation, he himself thereby commits a violation of neutrality, for which he may be made responsible by a belligerent who has suffered through the violation of neutrality committed by the other belligerent and acquiesced in by him.” (Ibid, 497). The recognition of the so-called Republic of Hawai‘i did not create any legality or lawfulness on the part of the puppet regime, but rather is the indisputable evidence that these States’ violated their duty to be neutral. Diplomatic recognition of governments occurs during a state of peace and not during a state of war, unless providing recognition of belligerency status. The recognitions were not recognizing the Republic as a belligerent in a civil war with the Hawaiian Kingdom, but rather under the false pretense that the Republic succeeded in a revolution and therefore was the new government of Hawai‘i during a state of peace. As such, their relationship with the Hawaiian Kingdom has since been regulated by humanitarian law.

State of War—No Question

The state of war has ensued to date, only to be concealed by a false narrative promoted by the United States government that Hawai‘i was purportedly annexed in 1898 through American legislation (Sai, Slippery Path, 84-94), coupled with a formal policy of the war crime of denationalizing school children beginning in 1906. The purpose of the policy was to obliterate the national consciousness of the Hawaiian Kingdom in the minds of the children and replace it with American patriotism. Within three generations, the effect of the denationalization was nearly complete.

The Hawaiian Kingdom has been in a “legal” state of war with the United States for over a century and the application of the laws of occupation and applicable humanitarian law has not diminished. Without a treaty between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States to return the state of affairs back to a state of peace, the state of war continues. As Judge Greenwood stated, “Countries were either in a state of peace or a state of war; there was no intermediate state.”

This is the longest state of war ever to have taken place in the history of international relations, which has created a humanitarian crisis of unimaginable proportions. International humanitarian laws apply, which includes customary international law regarding war and neutrality, 1907 Hague Regulations and the 1949 Geneva Conventions.

November 28th is the most important national holiday in the Hawaiian Kingdom. It is the day Great Britain and France formally recognized the Hawaiian Islands as an “independent state” in 1843, and has since been celebrated as “Independence Day,” which in the Hawaiian language is “La Ku‘oko‘a.” Here follows the story of this momentous event from the Hawaiian Kingdom Board of Education history textbook titled “A Brief History of the Hawaiian People” published in 1891.

**************************************

The First Embassy to Foreign Powers—In February, 1842, Sir George Simpson and Dr. McLaughlin, governors in the service of the Hudson Bay Company, arrived at Honolulu  on business, and became interested in the native people and their government. After a candid examination of the controversies existing between their own countrymen and the Hawaiian Government, they became convinced that the latter had been unjustly accused. Sir George offered to loan the government ten thousand pounds in cash, and advised the king to send commissioners to the United States and Europe with full power to negotiate new treaties, and to obtain a

on business, and became interested in the native people and their government. After a candid examination of the controversies existing between their own countrymen and the Hawaiian Government, they became convinced that the latter had been unjustly accused. Sir George offered to loan the government ten thousand pounds in cash, and advised the king to send commissioners to the United States and Europe with full power to negotiate new treaties, and to obtain a guarantee of the independence of the kingdom.

guarantee of the independence of the kingdom.

Accordingly Sir George Simpson, Haalilio, the king’s secretary, and Mr. Richards were appointed joint ministers-plenipotentiary to the three powers on the 8th of April, 1842.

Mr. Richards also received full power of attorney for the king. Sir George left for Alaska, whence he traveled through Siberia, arriving in England in November. Messrs. Richards and Haalilio sailed July 8th, 1842, in a chartered schooner for Mazatlan, on their way to the United States*

Mr. Richards also received full power of attorney for the king. Sir George left for Alaska, whence he traveled through Siberia, arriving in England in November. Messrs. Richards and Haalilio sailed July 8th, 1842, in a chartered schooner for Mazatlan, on their way to the United States*

*Their business was kept a profound secret at the time.

Proceedings of the British Consul—As soon as these facts became known, Mr. Charlton followed the embassy in order to defeat its object. He left suddenly on September 26th, 1842, for London via Mexico, sending back a threatening letter to the king, in which he informed him that he had appointed Mr. Alexander Simpson as acting-consul of Great Britain. As this individual, who was a relative of Sir George, was an avowed advocate of the annexation of the islands to Great Britain, and had insulted and threatened the governor of Oahu, the king declined to recognize him as British consul. Meanwhile Mr. Charlton laid his grievances before Lord George Paulet commanding the British frigate “Carysfort,” at Mazatlan, Mexico. Mr. Simpson also sent dispatches to the coast in November, representing that the property and persons of his countrymen were in danger, which introduced Rear-Admiral Thomas to order the “Carysfort” to Honolulu to inquire into the matter.

Recognition by the United States—Messres. Richards and Haalilio arrived in Washington early in December, and had several interviews with Daniel Webster, the Secretary of State, from whom they received an official letter December 19th, 1842, which recognized the independence of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and declared, “as the sense of the government of the United States, that the government of the Sandwich Islands ought to be respected; that no power ought to take possession of the islands, either as a conquest or for the purpose of the colonization; and that no power ought to seek for any undue control over the existing government, or any exclusive privileges or preferences in matters of commerce.” *

Secretary of State, from whom they received an official letter December 19th, 1842, which recognized the independence of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and declared, “as the sense of the government of the United States, that the government of the Sandwich Islands ought to be respected; that no power ought to take possession of the islands, either as a conquest or for the purpose of the colonization; and that no power ought to seek for any undue control over the existing government, or any exclusive privileges or preferences in matters of commerce.” *

*The same sentiments were expressed in President Tyler’s message to Congress of December 30th, and in the Report of the Committee on Foreign Relations, written by John Quincy Adams.

Success of the Embassy in Europe—The king’s envoys proceeded to London, where they had been preceded by the Sir George Simpson, and had an interview with the Earl of Aberdeen, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, on the 22d of February, 1843.

they had been preceded by the Sir George Simpson, and had an interview with the Earl of Aberdeen, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, on the 22d of February, 1843.

Lord Aberdeen at first declined to receive them as ministers from an independent state, or to negotiate a treaty, alleging that the king did not govern, but that he was “exclusively under the influence of Americans to the detriment of British interests,” and would not admit that the government of the United States had yet fully recognized the independence of the islands.

Sir George and Mr. Richards did not, however, lose heart, but went on to Brussels March 8th, by a previous arrangement made with Mr. Brinsmade. While there, they had an interview with Leopold I., king of the Belgians, who received them with great courtesy, and promised to use his influence to obtain the recognition of Hawaiian independence. This influence was great, both from his eminent personal qualities and from his close relationship to the royal families of England and France.

Encouraged by this pledge, the envoys proceeded to Paris, where, on the 17th, M. Guizot, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, received them in the kindest manner, and at once engaged, in behalf of France, to recognize the independence of the islands. He made the same statement to Lord Cowley, the British ambassador, on the 19th, and thus cleared the way for the embassy in England.

They immediately returned to London, where Sir George had a long interview with Lord Aberdeen on the 25th, in which he explained the actual state of affairs at the islands, and received an assurance that Mr. Charlton would be removed. On the 1st of April, 1843, the Earl of Aberdeen formally replied to the king’s commissioners, declaring that “Her Majesty’s Government are willing and have determined to recognize the independence of the Sandwich Islands under their present sovereign,” but insisting on the perfect equality of all foreigners in the islands before the law, and adding that grave complaints had been received from British subjects of undue rigor exercised toward them, and improper partiality toward others in the administration of justice. Sir George Simpson left for Canada April 3d, 1843.

Recognition of the Independence of the Islands—Lord Aberdeen, on the 13th of June, assured the Hawaiian envoys that “Her Majesty’s government had no intention to retain possession of the Sandwich Islands,” and a similar declaration was made to the governments of France and the United States.

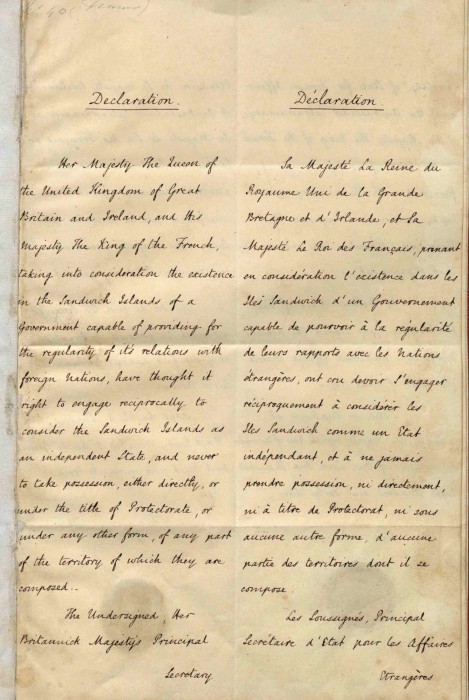

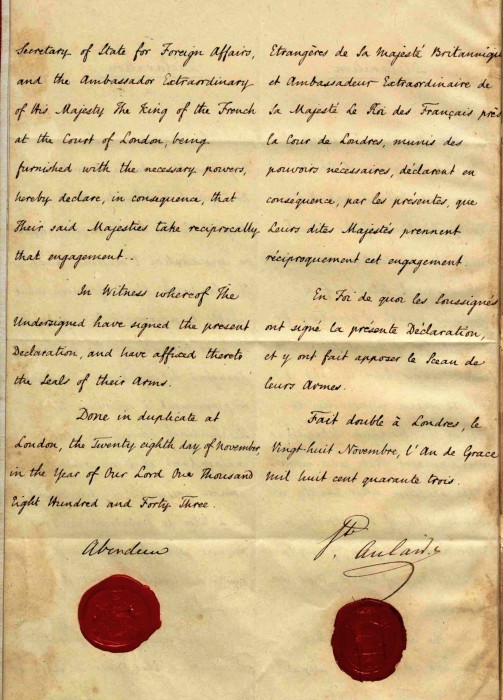

At length, on the 28th of November, 1843, the two governments of France and England united in a joint declaration to the effect that “Her Majesty, the queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and His Majesty, the king of the French, taking into consideration the existence in the Sandwich Islands of a government capable of providing for the regularity of its relations with foreign nations have thought it right to engage reciprocally to consider the Sandwich Islands as an independent state, and never to take possession, either directly or under the title of a protectorate, or under any other form, of any part of the territory of which they are composed…”

This was the final act by which the Hawaiian Kingdom was admitted within the pale of civilized nations. Finding that nothing more could be accomplished for the present in Paris, Messrs. Richards and Haalilio returned to the United States in the spring of 1844. On the 6th of July they received a dispatch from Mr. J.C. Calhoun, the Secretary of State, informing them that the President regarded the statement of Mr. Webster and the appointment of a commissioner “as a full recognition on the part of the United States of the independence of the Hawaiian Government.”

This was the final act by which the Hawaiian Kingdom was admitted within the pale of civilized nations. Finding that nothing more could be accomplished for the present in Paris, Messrs. Richards and Haalilio returned to the United States in the spring of 1844. On the 6th of July they received a dispatch from Mr. J.C. Calhoun, the Secretary of State, informing them that the President regarded the statement of Mr. Webster and the appointment of a commissioner “as a full recognition on the part of the United States of the independence of the Hawaiian Government.”

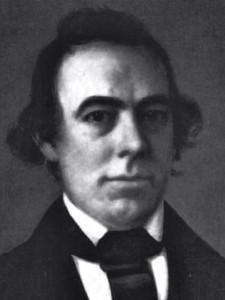

Below is a reprint of an article published in the Polynesian newspaper in 1845. The author is William Richards being one of the commissioners along with Timoteo Ha‘alilio and Sir George Simpson who were commissioned by King Kamehameha III with the purpose of securing the recognition of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State from Great Britain, France and the United States. Of the three, Ha‘alilio did not survive. He passed away on the ship The Montreal on his way home after departing Hawai‘i in 1842.

Below is a reprint of an article published in the Polynesian newspaper in 1845. The author is William Richards being one of the commissioners along with Timoteo Ha‘alilio and Sir George Simpson who were commissioned by King Kamehameha III with the purpose of securing the recognition of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State from Great Britain, France and the United States. Of the three, Ha‘alilio did not survive. He passed away on the ship The Montreal on his way home after departing Hawai‘i in 1842.

THE POLYNESIAN.

OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE HAWAIIAN GOVERNMENT.

HONOLULU, SATURDAY, MARCH 29, 1845.

The Montreal, from Boston, arrived off our harbor on Sunday last, at day break. Her ensign was noticed to be half-mast, and various conjectures began to circulate through the town, when William Richards, Esq., H.H.M.’s Commissioner to the U. States and Europe, whose arrival has been so long and anxiously awaited, landed and proceeded directly to the palace, where he immediately made known to their Majesties the melancholy news of the death of his fellow Commissioner, Mr. T. Haalilio, who died at sea on the 3d Dec. ult. The sad intelligence soon spread over the place; the flags of the men of war, merchant vessels, the consulates, batteries and other places, were immediately lowered to half-mast as a general expression of sympathy at the nation’s loss. Great hopes had been entertained both among Hawaiians and foreigners, of the good results that would ensue to the kingdom from the addition to its councils of one of so intelligent a mind, stored as it was with the fruits of observant travel, and the advantages derived from long and familiar intercourse in the best circles of Europe and the United States. A numerous band of personal friends to whom he had been endeared from his earliest intercourse by his sincerity of manners and peculiarly affectionate deportment, were earnestly looking to welcome him home. But above all, their Majesties, his intimate friends, the Governors, the other high chiefs and his widowed mother were awaiting his arrival with an earnestness of hope that the deepest affections of the heart can alone produce. The last tidings from him had been those of health. He was then soon to embark, and his speedy arrival to the shores and friends he loved so well, was anticipated without a doubt. So unexpected a termination of his existence, after having escaped the dangers of long and trying journe[y]s and voyagings, while as it were, on the very eve of again treading his native land, brings with it more than common anguish. It is not for us to life the veil and expose the scene which ensued at the palace upon the communication of the tidings. The whole court were there assembled. Those who had been suddenly deprived of their choicest hope when on the eve of its full indulgence, can alone estimate the bereavement.

The Montreal, from Boston, arrived off our harbor on Sunday last, at day break. Her ensign was noticed to be half-mast, and various conjectures began to circulate through the town, when William Richards, Esq., H.H.M.’s Commissioner to the U. States and Europe, whose arrival has been so long and anxiously awaited, landed and proceeded directly to the palace, where he immediately made known to their Majesties the melancholy news of the death of his fellow Commissioner, Mr. T. Haalilio, who died at sea on the 3d Dec. ult. The sad intelligence soon spread over the place; the flags of the men of war, merchant vessels, the consulates, batteries and other places, were immediately lowered to half-mast as a general expression of sympathy at the nation’s loss. Great hopes had been entertained both among Hawaiians and foreigners, of the good results that would ensue to the kingdom from the addition to its councils of one of so intelligent a mind, stored as it was with the fruits of observant travel, and the advantages derived from long and familiar intercourse in the best circles of Europe and the United States. A numerous band of personal friends to whom he had been endeared from his earliest intercourse by his sincerity of manners and peculiarly affectionate deportment, were earnestly looking to welcome him home. But above all, their Majesties, his intimate friends, the Governors, the other high chiefs and his widowed mother were awaiting his arrival with an earnestness of hope that the deepest affections of the heart can alone produce. The last tidings from him had been those of health. He was then soon to embark, and his speedy arrival to the shores and friends he loved so well, was anticipated without a doubt. So unexpected a termination of his existence, after having escaped the dangers of long and trying journe[y]s and voyagings, while as it were, on the very eve of again treading his native land, brings with it more than common anguish. It is not for us to life the veil and expose the scene which ensued at the palace upon the communication of the tidings. The whole court were there assembled. Those who had been suddenly deprived of their choicest hope when on the eve of its full indulgence, can alone estimate the bereavement.

It is satisfactory to know that every attention affection or sympathy could suggest, was afforded the deceased. Previous to our own departure from the United States, we were a witness to the deep interest and respect which Mr. Haalilio received in the refined society of Boston. But our already crowded columns will not allow us further to dilate. From Mr. Richards he received in all stages of his journey the most unremitting care, and towards the close of his life he was ever at his bed-side. Our readers will be able to glean from the brief memoir which follows this, prepared by Mr. R. some further insight into his life and untimely end. We say untimely, but man seeeth not as god seeeth.

Haalilio was born in 1808, at Koolau; Oahu. His parents were of respectable rank, and much esteemed. His father died while he was quite young, and his widowed mother subsequently married the Governor of Molokai, an island depend[e]nt on the Governor of Maui. After this death, she retained the authority of the island, and acted as Governess for the period of some fifteen years.

At the age of about eight years, Haalilio removed to Hilo on Hawaii, where he was adopted in the family, and became one of the playmates, of the young prince, now King of the Islands. He traveled round to different parts of the Islands with the prince, conforming to the various heathenish rites which were then in vogue. From that period he remained one of the most intimate companions and associates of the King.

At the age of about thirteen, he commenced learning to read, and was a pleasant pupil and made great proficiency. There were then no regularly established schools, and he was a private pupil of Mrs. Bingham. He learned to read English as well as Hawaiian, though at that period he did not understand what he read. He was taught arithmetic and penmanship by Mr. Bingham, and was early employed by the King to do his writing–not as an official secretary, but as an amanuensis or clerk. As be advanced in years he had various duties and employments assigned him, requiring skill and responsibility. Being associated with the King, he was always received into society with him, and thus enjoyed various advantages which he prized very much and improved in the best manner. He thus became acquainted with the usages of good society which he never failed to adopt as fast as he became acquainted with them.

To him also the King committed the charge of his private purse, which he held till the time of his embarkation. It thus became his duty to make most of the purchases required by the King, and he thereby had opportunity to become acquainted with the detail of mercantile business, of which he acquired a very commendable knowledge. His habits of business were many of them worthy of imitation even by the most enlightened. He was in a good degree systematic, and was extremely careful of every thing committed to this charge.

Besides acquaintance with mercantile transactions, he also acquired a very full knowledge of the political relations of the country. He was a strenuous advocate for a constitutional and representative government, and aided not a little in effecting those changes by which the rights of the lower classes have been secured. He was well acquainted with the practical influence of the former system of government, and considered a change necessary to the welfare of the nation.

The King and Chiefs could not fail to see the real value of such a man, and they therefore promoted him to offices to which his birth would not, according to the old system, have entitled him. He was properly the Lieutenant-Governor of the Island of Oahu, and regularly acted as Governor during the absence of the incumbent. It was expected also that he would succeed the present Governor in his office, had he outlived him. He was also elected a member of the council of Nobles, and materially aided that body in their deliberations. At the last meeting of the Legislature previous to his leaving the country, he was chosen President of the Treasury Board, and thus in a considerable degree he had control of the finances of the nation.

In the month of April, 1842, he was appointed a joint Commissioner with Mr. Richards, to the Courts of the U.S.A, England and France. He embarked on the 18th of July following on board the sch. Shaw, and arrived at Mazatlan Sept. 1st. While on the passage he often talked of home and friends with a tenderness and emotion that showed a high degree of sensibility and refinement. On his arrival at port, he was received with great hospitality. In crossing Mexico, he was deeply interested in noticing the peculiarities of the scenery, the character of the people, and the natural history of the country. Nothing escaped his observation; and the correctness and good sense of his remarks, rendered him not merely a pleasant but a profitable companion. After spending a fortnight at Vera Cruz, he was by the politeness of Capt. Newton received on board the U.S. steamer Missouri, about to sail to the mouth of the Mississippi. On board that vessel he had the company of Mr. Mayer, the U.S. Sec. of Legation at Mexico; and Mr. Southall, Bearer of Despatches, with whom he proceeded to New Orleans, and then by the mail route to Washington, where he arrived on the 3d of Dec. The results of his embassy there, are already before the public. After spending a month at Washington, and having accomplished the main objects of embassy there, he proceeded to the north, making a short stay of only two days in New York; but on his arrival in the western part of Massachusetts, was attacked by a severe cold, brought on by the inclemencies of the weather, followed by a change in the thermometer of about sixty degrees in twenty-four hours. Here was probably laid the foundation of that disease by which his short but eventful life has been so afflictingly closed.

He however so far recovered that he embarked for England in the steamer Caledonia, on the 2d of Feb. 1843, and arrived in London on the 18th of the same month, and was apparently at that time in perfect health. He immediately entered on the business of his embassy, and before six weeks had expired, had the happiness to receive from the Earl of Aberdeen, the official and solemn declaration that “Her Majesty’s Government are willing and have determined to recognize the independence of the Sandwich Islands under their present Sovereign.” He was also received and treated with high consideration by all persons of distinction to whom he was introduced. The Hon. Mr. Ellis; Sir Henry Pelly; the Earl of Selkirk; the Duke and Duchess of Sommerset; Sir Augustus d’Este, cousin of the Queen; the Lord Chamberlain; and the Mayor of London, were among the number of those from whom he received special attentions. While in Europe, as well as in the U.S.A., he made it a special business to visit and examine all objects of public interest which claim the attention of the traveller. The various manufacturing establishments, the museums, the hospitals, the prisons, the great works of architecture, the ancient palaces and cathedrals, the bridges, dockyards, and mausoleums of the dead,–the public schools and institutions of charity, and various religious establishments; all received his attention, and produced an influence on his mind which it was most interesting to witness.

After accomplishing the object of his embassy to England, he proceeded to France, where he was received in the same respectful manner as in England, and after carious delays, finally succeeded in obtaining from the French Government, not only a recognition of independence, but also a mutual guarantee from England and France that that independence should be respected. In Belgium he was honored with an interview with the King Leopold, and received the same recognition of independence as had been obtained from the other nations. The persons from whom he received special attentions in France, were M. Guizot; Count and Countess Gasparin; the Lafayette family; Count de la Bonde; Duke de Caze; Admiral Baudin; Duke de Broglie; the Baron Champloies; Count Pellet; Count Salvandy; M. de Toqueville; Lady Elgin, and others. In all the society he visited, he never failed to secure entire respect.

After spending about fifteen months in Europe, he returned to the U. S. A. in the Britannia, and reached Boston on the 18th of May ult. It should have been mentioned however, that while in Paris in June 1843, he was affected by a cold, rheumatic pains and coughs, which soon yielded to medical treatment, and his health again became good. But in Jan. last he was more seriously afflicted, being confined to his room, and mostly to his bed, for a period of more than four weeks. At this time his cough was very severe, the soreness of his breast great, and his symptoms in many respects threatening. He soon recovered, however, and on his arrival in the U.S.A. was in good health. He spent most of the summer in traveling. He visited Washington again, and proceeded to Wheeling, Va.; thence to Pittsburg, and on to Cleveland, Ohio, and down the lake to Buffalo, and Niagara Falls; thence through lake Ontario to Syracuse, Albany, and down the Hudson to New York.

He subsequently returned to Albany, and thence on through White-Hall and lake Champlain to Montreal in Canada. He returned through the interior of Vermont and New Hampshire to Boston, where he spent a few weeks, visiting the various places of importance in that vicinity; Cambridge, Charleston, Roxbury, Plymouth, Quincey, Newburyport, Andover, Lowell, and other places. It is impossible to describe the interest that he took in these visits, or the profit he appeared to derive from them.

But it is now time to revert to another trait in his character; I mean his religious views and affections.

But a few days after we embarked from the Islands, as he opened his trunk, I noticed the Hawaiian Bible lying in it, which he took and began to read. This was the commencement of a practice which he followed till his frame was too weak to follow it longer. Few if any days passed except when actually traveling or employed in important business, in which he was not seen reading that precious book. A few days previous to his death he told me he had read it twice through in course since he left the Islands, beside all his incidental reading. Besides the Scriptures, he read much in other books of a religious character, though his reading was by no means confined to nor was it principally religious books. After exhausting his Hawaiian library, he read considerable in English.

To show his feelings on the subject of prayer, I will mention, that after traveling in Mexico for a number of successive days, and every night being in the midst of company and bustle, without a possibility of retirement, we at last arrived at the hospitable dwelling of an E[n]glish gentlemen, who at bed time conducted us to a retired and pleasant chamber. Our host had scarcely left us when Haalilio turned his eyes and surveying the room for a moment said with an expressive countenance, “We have at last found a place where we can pray.” He showed that he was not a stranger to prayer. The apparent humility with which he made confession of sins, the fervency with which he asked Divine aid in the business of our embassy, and the tenderness with which he implored the blessing of Heaven on his friends and countrymen, early led me to feel that prayer with him was not a mere empty form. From that time down to the last sad hour of his life, I had evidence that in a good degree he kept the commandment.—”Be instant in prayer.” Many and many a night when he supposed me to be asleep, have I heard his voice or rather whisper, laying open his heart before his Maker.

By the deep interest which he manifested in a faithful observance of the Sabbath, he showed that he was not regardless of the Divine requisitions. While in France and Belgium, never a Sabbath passed in which he did not express his astonishment at the public, open, and constant violation of God’s holy day. On the contrary, while in England and the U. S. A. he as often expressed his admiration as he witnessed the stillness of the streets and the multitudes of those who thronged the house of God.

The illness which terminated his life commenced on the 13th of Sept. last, while in Brooklyn, New York. At first he merely complained of slight rheumatic pain, and indisposition to exercise. At the end of a week it suddenly increased and exhibited the usual marks of a cold. Medicine was promptly administered, and after keeping his room for a week, he was so much better as to leave it and take exercise in open air. But as he recovered from his rheumatism, I noticed an increase of cough, especially in the morning. To this I called the attention of the physician. He considered the cough as merely symptomatic, and giving a common cough mixture, predicted its early removal. On the 16th of Oct. he removed to Boston, and the first physicians of the city were immediately called. They pronounced his lungs sound, and his disease to be a slow fever. On the third day however, their opinion changed, and they thought his lungs affected, but not seriously. At their advice, and the advice of numerous other friends, he was removed to the Massachusetts Hospital, where every thing was done which science could prescribe, or medicine effect. But his disease made rapid strides, and his flesh wasted fast.

During the whole period of his illness he took a rational and correct view of his own case. He early discovered the danger of his symptoms, yet never appeared alarmed, nor renounced the hope of recovery, until a few days previous to his death. And in all circumstances he appeared calm and resigned, saying, “Father, not my will but thine be done.” While at the Hospital, I heard him whisper this in prayer, at the still hour of midnight, while he supposed I was asleep. On one occasion, I noticed him wiping the tear from his cheek, and went to his bedside to sympathi[z]e and comfort him. He immediately said, “I was not weeping for myself, but for you.” I inquired if he was not anxious to live and reach the Islands. He replied, “Not on my own account. I [s]hould indeed be glad to tell the chiefs and people what I have seen, and in their presence dedicate myself to God; but respecting myself I do not feel anxious.” The great subjects of those prayers which I overheard were confessions of sin, pleading for relief from suffering, imploring blessings on his mother, on the King and on his countrymen. He prayed also that he might live to reach the Islands; but this prayer was usually conditional, and ended with “Aia no ia oe”–it is with thee, or, they will be done. Before he came on board, he dictated a few affecting sentences to the King and Chiefs.–The second Sabbath we were at sea, he became convinced that he could not live, and gave farther charge to be delivered to the King and Chiefs. He expressed also a wish to be bapti[z]ed. On the evening of that Sabbath, while speaking of his pain and sufferings and immediate prospect of death, he added, “But this is the happiest day of my life. My work is done. I am ready to go.” He continued in the same general state of mind to the time of his departure. During the last few hours of his life he prayed several times, but I only understood one important sentence, which was nearly like this: “My Father, thou hast not granted my desire, once more to see the land of my birth, and my friends there, but do not, I entreat thee, refuse my request to see they kingdom, and my friends who are dwelling with thee.” At about four o’clock he slapped his arms about my neck, pulled my face down to his, and kissed me, then said, “Heaha ke koe?” What further remains? I replied, “Eternal life in Heaven, if you believe in Jesus. He will be your King, and angels will be your associates; there will be no groans there, no parting, no weakness, no anguish or pain, and no sin.” He replied, “That is plain; I understand it well; but I have no painful anxiety on that subject, and it was not to that that my question related. What further have I to do here?” I replied, “It is with the Lord; I know not: all your charges to me I have put down in writing, and shall faithfully deliver them according to your directions.” A little while after, he reached out his hand, took hold of mine and shook it with a smile, and then let go. At a quarter before seven, I perceived his again in prayer; but his voice soon died away, and I perceived that his end was near; and at seven, his spirit took its flight.

***UPDATE. Lorenz Gonschor successfully defended his dissertation. He will be graduating in May 2016 with a Ph.D. in political science. His committee members were comprised of Associate Professor Noelani Goodyear–Ka‘ōpua, Committee Chair, Professor John Wilson, Associate Professor Ehito Kimura, Assistant Professor Colin Moore, Professor Niklaus Schweizer, and Assistant Professor Kamana Beamer.

According to the Office of Graduate Education at the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa, all doctoral dissertation defenses are open to the public.

Kale Gumapac, host of Kanaka Express, interviews Dr. Niklaus Schweizer on history of the Hawaiian Kingdom and its impact today. Dr. Schweizer is a professor at the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa and has published books and articles on the history of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Dr. Schweizer also served as the Honorary Consul for the Swiss Confederation and is currently consul emeritus of the Consular Corps of Hawai‘i.

https://vimeo.com/150326365

https://vimeo.com/150326366

As the Hawaiian Kingdom approaches the celebration of its most important national holiday Lā Ku‘oko‘a (Independence Day) on November 28—Saturday, it is important to understand just what the term “independence” really means. Common misunderstandings are statements such as “independence advocates” or “people who want Hawaiian independence.” These statements assume Hawai‘i is not independent, where independence is a political aspiration and not a legal reality. It is also evidence of denationalization through Americanization that has nearly obliterated the national consciousness of the Hawaiian Kingdom in the minds of the people.

In international relations and law, independence reflects the status of a State whereby the international community recognizes that only the laws of that particular State apply over its territory “independent” of other laws over other States and their territories. Only independent States are subjects of international law or members or the Family of Nations. In other words you can be a State, but not be independent, such as the State of New York, which once was an independent State but is no longer today.

After the American Revolution, the State of New York became an independent State along with the other former twelve British colonies, who were all member States of a political union called the United Stated States of America, which was a confederation since 1777. A confederation is a political union of independent States, such as today’s European Union, which is a commercial union of independent States.

Article 1 of the 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the American Revolution, specifically states, “His Brittanic Majesty acknowledges the said United States, viz., New Hampshire, Massachusetts Bay, Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia, to be free sovereign and Independent States.” For the next six years, the international community recognized that only New York law applied over the territory of New York to the exclusion of any foreign States’ laws, such as the laws of Great Britain and France.

In 1789, New York would lose its independence of its laws when it chose to join an American Federation whereby all thirteen American independent States would relinquish their independence to a Federal government thereby creating the United States of America as the world knows it today. This is when the United States of America replaced the former thirteen independent States as the single independent State under international law. No longer being an independent State, New York has two separate laws that apply with equal force within its territory—United States Federal law and State of New York law.

When Great Britain and France jointly proclaimed on November 28, 1843 that both States recognized the Hawaiian Kingdom as an Independent State, it meant that only Hawaiian law would apply over Hawaiian territory, which signified Hawaiian independence. Even more surprising was that the Hawaiian Kingdom was the only non-European Power admitted into the Family of Nations with full recognition of its independence of Hawaiian law over Hawaiian territory.

Other non-European Powers such as Japan were not admitted as independent States into the Family of Nations until 1899, and since 1858, Japan had unequal treaties whereby independent States, such as the United States of America, applied their own laws within Japanese territory over their citizenry. Under the 1858 American-Japanese unequal treaty, American citizens could only be prosecuted in Japan under American law and tried by the American Consulate serving as the Court. The Hawaiian Kingdom also had an unequal treaty with Japan. Under the 1871 Hawaiian-Japanese Treaty, Hawaiian subjects in Japan could only be prosecuted under Hawaiian law by the Hawaiian Consulate in Tokyo.

Since the American occupation began, Hawaiian independence is at the core of the law of occupation. This means only Hawaiian law must be temporarily administered by the occupying State. No other law can be administered in an occupied State because it is independent. The laws of occupation would not apply if Hawai‘i was not an independent State.

In international arbitration between the Netherlands and the United States at the Permanent Court of Arbitration (Island of Palmas case) from 1925-1928, the arbitrator explained independence. Judge Huber stated, “Sovereignty in the relations between States signifies independence. Independence in regard to a portion of the globe is the right to exercise therein, to the exclusion of any other State, the functions of a State.”

Independence refers to “political” independence and not “physical” independence from another State. Oppenheim, International Law, Vol. 1, 177-8 (2nd ed. 1912), explains: “Sovereignty as supreme authority, which is independent of any other earthly authority, may be said to have different aspects. As excluding dependence from any other authority, and in especial from the authority of the another State, sovereignty is independence. It is external independence with regard to the liberty of action outside its borders in the intercourse with other States which a State enjoys. It is internal independence with regard to the liberty of action of a State inside its borders. As comprising the power of a State to exercise supreme authority over all persons and things within its territory, sovereignty is territorial supremacy. As comprising the power of a State to exercise supreme authority over its citizens at home and abroad, sovereignty is personal supremacy. For these reasons a State as an International Person possesses independence and territorial and personal supremacy.”

Occupation does not extinguish independence/sovereignty, but rather it is protected and maintained under international law. U.S. Army FM-27-10, The Law of Land Warfare, acknowledges this. Chapter 6 covers occupation. Section 358 states, “Being an incident of war, military occupation confers upon the invading force the means of exercising control for the period of occupation. It does not transfer the sovereignty to the occupant, but simply the authority or power to exercise some of the rights of sovereignty. The exercise of these rights results from the established power of the occupant and from the necessity of maintaining law and order, indispensable both to the inhabitants and to the occupying force. It is therefore unlawful for a belligerent occupant to annex occupied territory or to create a new State therein while hostilities are still in progress.”

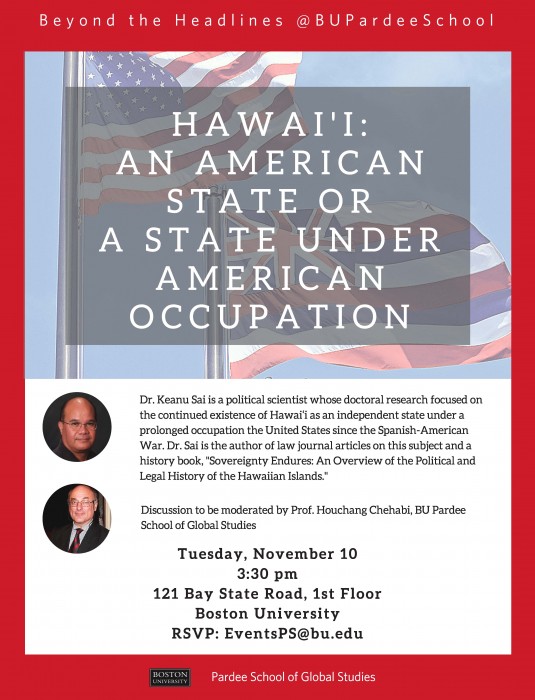

Lecture Series “Beyond the Headlines” Boston University Pardee School of Global Studies presents: “Hawai’i: An American State or a State Under American Occupation?”

An interview of Professor Niklaus Schweizer and Ph.D. candidate Lorenz Gonschor from the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa by Kale Gumapac, host of the show The Kanaka Express. The interview is focuses on dispelling the untruths of the Hawaiian Kingdom that is a part of the research and classroom instruction at the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa.

https://vimeo.com/143006284

An interview of Dr. Keanu Sai and Ph.D. candidate Lorenz Gonschor by Dr. Lynette Cruz on Issues that Matter. The subject of the interview focused on the Hawaiian Kingdom as a non-European Power in the nineteenth century and its relationship with Japan.

https://vimeo.com/142326302