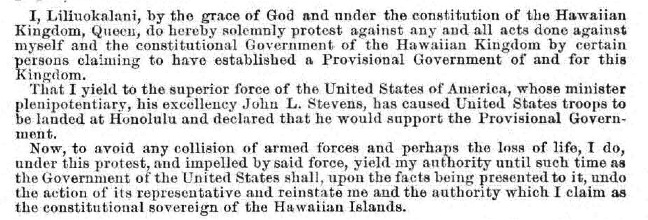

In 1995, the dominant view of sovereignty was centered on ethnicity—the aboriginal (native) Hawaiian, and, as a people, its endeavor was to achieve either sovereignty through independence or a limited sovereignty within the United States. In other words, sovereignty was not a reality vested in an already established independent State as we now understand the term, but rather it was perceived as a political aspiration of a native people seeking sovereignty, thus giving rise to a sovereignty movement where you have some groups advocating for independence from the United States, while other groups advocating for limited sovereignty under United States law. The United States 1993 Congressional Apology Resolution for the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government merely reinforced this view and portrayed native Hawaiians as a group similar to Native Americans. This was not an accurate portrayal of Hawai‘i’s political and legal history.

According to the government census in 1890, the majority of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s citizenry were aboriginal Hawaiians at 86% and the remaining 14% were non-aboriginal. The Hawaiian Kingdom was not based on ethnicity, but rather the rule of law, and the citizenry was also opened through naturallization and denization or through birth on Hawaiian territory – natural born. The international law of occupation, however, prevents the acquisition of the citizenship of the Hawaiian Kingdom through birth on Hawaiian territory, and limits the acquisition of Hawaiian citizenship to parentage. In other words, the citizenry of the Hawaiian Kingdom today is limited to people who are direct descendants of Hawaiian subjects, irrespective of their race, color or creed, that were Hawaiian subjects on August 12, 1898, which was the beginning of the prolonged occupation.

Already armed with the knowledge that the Hawaiian Kingdom was a recognized State under international law since November 28, 1843, and that the unlawful overthrow of the Hawaiian government on January 17, 1893 by the United States did not equate to an overthrow of Hawaiian State sovereignty, extraordinary steps were taken in order to establish an acting government through a process provided for by Hawaiian Kingdom law as it existed in 1893, and by the legal doctrine of necessity. On December 15, 1995, a general partnership was formed under the 1880 Act to Provide for the Registration of Co-partnership Firms with the specific purpose to serve as an acting government in the absence of the monarch who was the chief executive of Hawaiian law and administration of government. A plan was devised to activate a regent under  Article 33 of the Hawaiian Constitution to temporarily serve in the absence of a monarch, because to claim to be a monarch would be a direct violation of Hawaiian law. Since the death of Prince Kuhio Kalaniana‘ole in 1922, the last proclaimed heir to the throne prior to the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian government, only the Legislative Assembly has the authority under Article 22 of the Hawaiian Constitution to elect by ballot a new monarch—any other claimant would be self-proclaimed. Lunalilo was elected King by the Legislative Assembly under Article 22 of the Constitution on January 8, 1873 because King Kamehameha V was not able to confirm an heir under Hawaiian law, and the following year, David Kalakaua was elected King under Article 22 because King Lunalilo was not able to confirm an heir as well. A regency was the only legal option to reactivate the government.

Article 33 of the Hawaiian Constitution to temporarily serve in the absence of a monarch, because to claim to be a monarch would be a direct violation of Hawaiian law. Since the death of Prince Kuhio Kalaniana‘ole in 1922, the last proclaimed heir to the throne prior to the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian government, only the Legislative Assembly has the authority under Article 22 of the Hawaiian Constitution to elect by ballot a new monarch—any other claimant would be self-proclaimed. Lunalilo was elected King by the Legislative Assembly under Article 22 of the Constitution on January 8, 1873 because King Kamehameha V was not able to confirm an heir under Hawaiian law, and the following year, David Kalakaua was elected King under Article 22 because King Lunalilo was not able to confirm an heir as well. A regency was the only legal option to reactivate the government.

According to the Co-partnership Act, Hawaiian Kingdom law required partnership agreements to be recorded in the Bureau of Conveyances as part of the registration process with the Minister of Interior. Today, the Bureau of Conveyances still exists and you will find partnership agreements that have been registered since 1880 to 1893. In fact, the State of Hawai‘i governmental infrastructure is the governmental infrastructure of the Hawaiian Kingdom. All that was changed since 1893 were the titles and additional departments, i.e. Monarch to Governor, Governors to Mayors, Department of Interior to Department of Land and Natural Resources, Department of Finance to Department of Accounting and General Services, Department of Education remained, Attorney General remained, Judicial Circuits remained, etc.

In its co-partnership agreement establishing the Hawaiian Kingdom Trust Company, which was recorded in the Bureau of Conveyances and assigned document no. 96-000263, the partnership agreement specifically states the “company will serve in the capacity of acting for and on behalf the Hawaiian Kingdom government.” It also provided that the “company has adopted the Hawaiian constitution of 1864 and the laws lawfully established in the administration of the same.” The Hawaiian Kingdom Trust Company was specifically established to regulate and ensure that Perfect Title Company, another co-partnership established on December 10, 1995, comply with the Co-partnership Act and Hawaiian Kingdom law.

The acting government was not established by virtue of Hawaiian Kingdom law, but rather by virtue of the legal doctrine of necessity though the use and application of Hawaiian Kingdom law. As in any constitutional government, there is an organizational infrastructure established under the constitution and laws that provides for its effective administration. Within this infrastructure, co-partnerships come under the direct supervision of the office of the Minister of the Interior; the Minister of the Interior sits on the Cabinet Council comprised of the Minister of Finance, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, and the Attorney General; and the Cabinet Council serves as a Council of Regency who serves in the absence of a monarch according to Article 33 of the Hawaiian constitution.

In the absence of individuals occupying these offices established by Hawaiian law since January 17, 1893, the Trustees of the Hawaiian Kingdom Trust Company took the necessary steps, under extraordinary circumstances and under the doctrine of necessity, to assume the offices directly in line from a co-partnership through the Minister of the Interior to the Council of Regency. This is analogous to a soldier with the rank of Private assuming the chain of command to Lieutenant, because everyone within the chain of command from Corporal to Sergeant to Staff Sergeant to Lieutenant were killed in action. Under Army regulations the most senior Private is obligated to assume the chain of command and is called acting Lieutenant in order to maintain the command structure. He remains the acting Lieutenant until a properly commissioned officer relieves him and then he returns to his original position as Private.

For a private company to assume the role of government is revolutionary, but in order for this action to not be considered treason, the doctrine of necessity can be used to justify the assumption of government. According to Professor de Smith in his book Constitutional and Administrative Law, deviations from a State’s constitutional order “can be justified on grounds of necessity.” He argues, “State necessity has been judicially accepted in recent years as a legal justification for ostensibly unconstitutional action to fill a vacuum arising within the constitutional order [and to] this extent it has been recognized as an implied exception to the letter of the constitution.” In 1986, the Court of Appeals of Grenada in Mitchell v. Director of Public Prosecutions, addressed the doctrine of necessity and provided the following conditions that would justify an action to assume the role of government.

- An imperative necessity must arise because of the existence of exceptional circumstances not provided for in the Constitution, for immediate action to be taken to protect or preserve some vital function of the State;

- There must be no other course of action reasonably available;

- Any such action must be reasonably necessary in the interest of peace, order, and good government; but it must not do more than is necessary or legislate beyond that;

- It must not impair the just rights of citizens under the Constitution; and,

- It must not be one the sole effect and intention of which is to consolidate or strengthen the revolution as such.

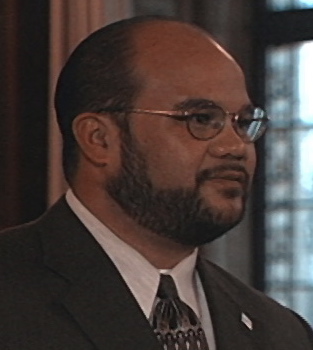

On March 1, 1996, the Trustees appointed David Keanu Sai, who later received his Ph.D. in 2008, to serve in the capacity as acting Regent to head the government. Dr. Sai is also the maternal great grandson of William Kuakini Simerson and the paternal great great grandson of Julia Kapapakuialii Kalaninuipoaimoku, both of whom who was confirmed by the Hawaiian Board of Genealogists of Hawaiian Chiefs to be “native chiefs” in conformity with the 1880 Act to Perpetuate the Genealogy of the Chiefs of Hawai‘i. The purpose of enacting the statute was provided in its preamble, which states:

- Whereas, it is provided by the 22d article of the Constitution that the Kings of Hawai‘i shall be chosen from the native chiefs of the Kingdom;

- And Whereas, at the present day it is difficult to ascertain who are the chiefs, as contemplated by said article of the Constitution, and it is proper that such genealogies of the Kingdom be perpetuated, and also the history of the chiefs and kings from ancient times down to the present day, which would also be a guide to the King in the appointment of Nobles in the Legislative Assembly

The Board of Genealogy of Hawaiian Chiefs was established by law to “collect from genealogical books, and from the knowledge of old people the history and genealogy of  the Hawaiian chiefs, and shall publish a book.” As a result of the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian government, however, the Board published the genealogies of native chiefs living at the time between April 20 and November 30, 1896 in the newspaper publication Ka Maka‘ainana.

the Hawaiian chiefs, and shall publish a book.” As a result of the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian government, however, the Board published the genealogies of native chiefs living at the time between April 20 and November 30, 1896 in the newspaper publication Ka Maka‘ainana.

After assuming the role of government, the acting Regency had to display some form of legal effects, which is a crucial element of legitimacy. In order for a government to be legitimate, it has to be effective both within its territory to enforce its laws and outside of its territory to enforce international law. An exception to the principle of effectiveness is the occupation by another State’s forces. According to Professor Marek in her book Identity and Continuity of States in Public International Law, “the legal order of the occupant (State) is…strictly subject to the principle of effectiveness, while the legal order of the occupied State continues to exist [despite] the absence of effectiveness. It can produce legal effects outside the occupied territory and may develop and expand, not by reason of its effectiveness, but solely on the basis of the positive international rule safeguarding its continuity.”

The first instance of exhibiting legal effects outside the occupied territory occurred when the acting government entered into an arbitration agreement with Lance Larsen, a Hawaiian national, to submit their dispute to the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague, Netherlands. In 2001, the American Journal of International Law reported:

- “At the center of the PCA proceeding was the argument that Hawaiians never directly relinquished to the United States their claim of inherent sovereignty either as a people or over their national lands, and accordingly that the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist and that the Hawaiian Council of Regency (representing the Hawaiian Kingdom) is legally responsible under international law for the protection of Hawaiian subjects, including the claimant. In other words, the Hawaiian Kingdom was legally obligated to protect Larsen from the United States’ ‘unlawful imposition [over him] of [its] municipal laws’ through its political subdivision, the State of Hawaii. As a result of this responsibility, Larsen submitted, the Hawaiian Council of Regency should be liable for any international law violations that the United States committed against him.”

The arbitral proceedings led to the United States de facto recognition of the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State, and the acting government as officers de facto of the Hawaiian Kingdom. In February 2000, the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s Secretary General Tjaco T. van den Hout recommended that the acting government provide a formal invitation to the United States to join in the arbitration. In order to carry out this request by the Secretary General, Dr. Sai was sent to Washington, D.C. Ms. Ninia Parks, attorney for the Claimant Lance Larsen, accompanied Dr. Sai.

The arbitral proceedings led to the United States de facto recognition of the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State, and the acting government as officers de facto of the Hawaiian Kingdom. In February 2000, the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s Secretary General Tjaco T. van den Hout recommended that the acting government provide a formal invitation to the United States to join in the arbitration. In order to carry out this request by the Secretary General, Dr. Sai was sent to Washington, D.C. Ms. Ninia Parks, attorney for the Claimant Lance Larsen, accompanied Dr. Sai.  On March 3, 2000, a telephone meeting with John R. Crook, Assistant Legal Adviser for United Nations Affairs section of the US Department of State, was held. It was stated to Mr. Crook that the “visit was to provide these documents to the Legal Department of the U.S. Department of State in order for the U.S. Government to be apprised of the arbitral proceedings already in train and that the Hawaiian Kingdom, by consent of the Claimant, extends an opportunity for the United States to join in the arbitration as a party.”

On March 3, 2000, a telephone meeting with John R. Crook, Assistant Legal Adviser for United Nations Affairs section of the US Department of State, was held. It was stated to Mr. Crook that the “visit was to provide these documents to the Legal Department of the U.S. Department of State in order for the U.S. Government to be apprised of the arbitral proceedings already in train and that the Hawaiian Kingdom, by consent of the Claimant, extends an opportunity for the United States to join in the arbitration as a party.”

Mr. Crook was made fully aware of the United States occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the establishment of the acting government. This direct challenge to US sovereignty over the Hawaiian Islands should have prompted the United States to protest the action taken by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in accepting the Hawaiian arbitration case and call upon the Secretary General to cease and desist because this action constitutes a violation of US sovereignty. The United States did neither. Instead, Deputy Secretary General Phyllis Hamilton notified the acting government that the United States notified the Court that it will not join in the arbitration, but did request from the acting government permission to access all pleadings and transcripts of the case. Both the acting government and Larsen’s attorney consented. By this action, the United States directly acknowledged the circumstances of the proceedings and the acting government as the legitimate representation of the Hawaiian Kingdom before an international tribunal.

On December 12, 2000, the day after oral hearings were held at the Permanent Court of Arbitration, a meeting took place in Brussels between Dr. Jacques Bihozagara, Ambassador for the Republic of Rwanda assigned to Belgium, and the acting government. The meeting was prompted by Ambassador Bihozagara who called the acting government at its hotel in The Hague, after the Ambassador was apprised of the arbitration proceedings while he was attending a hearing at the International Court of Justice on December 8, 2000, Democratic Republic of the Congo v. Belgium. At the meeting in Brussels, the Rwandan government directly acknowledged the acting government and offered their assistance in reporting to the United Nations General Assembly the prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom. In that meeting, the acting government decided it could not, in good conscience, accept the offer and place Rwanda in a position of reintroducing Hawaiian State continuity before the United Nations, when Hawai‘i’s community, itself, remained ignorant of Hawai‘i’s profound legal position as a result of institutionalized indoctrination. Although the Rwandan government took no action before the United Nations General Assembly, the offer itself, exhibited Rwanda’s de facto recognition of the acting government and the continuity of the Hawaiian State.

On December 12, 2000, the day after oral hearings were held at the Permanent Court of Arbitration, a meeting took place in Brussels between Dr. Jacques Bihozagara, Ambassador for the Republic of Rwanda assigned to Belgium, and the acting government. The meeting was prompted by Ambassador Bihozagara who called the acting government at its hotel in The Hague, after the Ambassador was apprised of the arbitration proceedings while he was attending a hearing at the International Court of Justice on December 8, 2000, Democratic Republic of the Congo v. Belgium. At the meeting in Brussels, the Rwandan government directly acknowledged the acting government and offered their assistance in reporting to the United Nations General Assembly the prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom. In that meeting, the acting government decided it could not, in good conscience, accept the offer and place Rwanda in a position of reintroducing Hawaiian State continuity before the United Nations, when Hawai‘i’s community, itself, remained ignorant of Hawai‘i’s profound legal position as a result of institutionalized indoctrination. Although the Rwandan government took no action before the United Nations General Assembly, the offer itself, exhibited Rwanda’s de facto recognition of the acting government and the continuity of the Hawaiian State.

Other examples of creating legal effects on the international plane include:

- China, as President of the UN Security Council, accepted a complaint by the acting government against the United States of America on July 5, 2001 under Article 35(2) of the United Nations Charter, which provides that States who are not members of the United Nations can file a dispute with the Security Council or General Assembly. By accepting the complaint, China recognized the acting government and the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom;

- Qatar, as President of the UN General Assembly accepted a Protest and Demand by the acting government against 173 member States of the United Nations on August 10, 2012 under Article 35(2) of the UN Charter. By accepting the complaint, Qatar, recognized the acting government and the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom;

- The International Criminal Court, by the Secretary General of the United Nations accepted the acting government accession to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court on December 10, 2012;

- Switzerland, by its Foreign Ministry, accepted the acting government’s instrument of accession acceding to the Fourth Geneva Convention on January 14, 2013.

- The International Court of Justice, by its Registrar, acknowledged receipt of the acting government’s Application Instituting Proceedings against 45 States on September 27, 2013.

The acting government, as nationals of an occupied State, took the necessary and extraordinary steps, by necessity and according to the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom and international law, to reestablish the Hawaiian government in an acting capacity in order to exercise our country’s preeminent right to “self-preservation” that was deprived through fraud and deceit; and for the past 13 years the acting government has acquired a customary right under international law in representing the Hawaiian State during this prolonged and illegal occupation.

For a detailed legal brief download “The Continuity of the Hawaiian State and the Legitimacy of the acting Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom.”