November 28th is the most important national holiday in the Hawaiian Kingdom. It is the day Great Britain and France formally recognized the Hawaiian Islands as an “independent state” in 1843, and has since been celebrated as “Independence Day,” which in the Hawaiian language is “La Ku‘oko‘a.” Here follows the story of this momentous event from the Hawaiian Kingdom Board of Education history textbook titled “A Brief History of the Hawaiian People” published in 1891.

**************************************

The First Embassy to Foreign Powers—In February, 1842, Sir George Simpson and Dr. McLaughlin, governors in the service of the Hudson Bay Company, arrived at Honolulu  on business, and became interested in the native people and their government. After a candid examination of the controversies existing between their own countrymen and the Hawaiian Government, they became convinced that the latter had been unjustly accused. Sir George offered to loan the government ten thousand pounds in cash, and advised the king to send commissioners to the United States and Europe with full power to negotiate new treaties, and to obtain a

on business, and became interested in the native people and their government. After a candid examination of the controversies existing between their own countrymen and the Hawaiian Government, they became convinced that the latter had been unjustly accused. Sir George offered to loan the government ten thousand pounds in cash, and advised the king to send commissioners to the United States and Europe with full power to negotiate new treaties, and to obtain a guarantee of the independence of the kingdom.

guarantee of the independence of the kingdom.

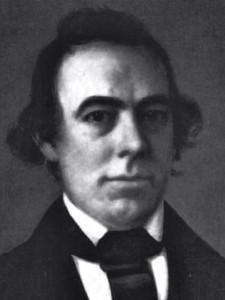

Accordingly Sir George Simpson, Haalilio, the king’s secretary, and Mr. Richards were appointed joint ministers-plenipotentiary to the three powers on the 8th of April, 1842.

Mr. Richards also received full power of attorney for the king. Sir George left for Alaska, whence he traveled through Siberia, arriving in England in November. Messrs. Richards and Haalilio sailed July 8th, 1842, in a chartered schooner for Mazatlan, on their way to the United States*

Mr. Richards also received full power of attorney for the king. Sir George left for Alaska, whence he traveled through Siberia, arriving in England in November. Messrs. Richards and Haalilio sailed July 8th, 1842, in a chartered schooner for Mazatlan, on their way to the United States*

*Their business was kept a profound secret at the time.

Proceedings of the British Consul—As soon as these facts became known, Mr. Charlton followed the embassy in order to defeat its object. He left suddenly on September 26th, 1842, for London via Mexico, sending back a threatening letter to the king, in which he informed him that he had appointed Mr. Alexander Simpson as acting-consul of Great Britain. As this individual, who was a relative of Sir George, was an avowed advocate of the annexation of the islands to Great Britain, and had insulted and threatened the governor of Oahu, the king declined to recognize him as British consul. Meanwhile Mr. Charlton laid his grievances before Lord George Paulet commanding the British frigate “Carysfort,” at Mazatlan, Mexico. Mr. Simpson also sent dispatches to the coast in November, representing that the property and persons of his countrymen were in danger, which introduced Rear-Admiral Thomas to order the “Carysfort” to Honolulu to inquire into the matter.

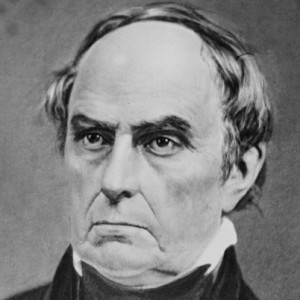

Recognition by the United States—Messres. Richards and Haalilio arrived in Washington early in December, and had several interviews with Daniel Webster, the Secretary of State, from whom they received an official letter December 19th, 1842, which recognized the independence of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and declared, “as the sense of the government of the United States, that the government of the Sandwich Islands ought to be respected; that no power ought to take possession of the islands, either as a conquest or for the purpose of the colonization; and that no power ought to seek for any undue control over the existing government, or any exclusive privileges or preferences in matters of commerce.” *

Secretary of State, from whom they received an official letter December 19th, 1842, which recognized the independence of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and declared, “as the sense of the government of the United States, that the government of the Sandwich Islands ought to be respected; that no power ought to take possession of the islands, either as a conquest or for the purpose of the colonization; and that no power ought to seek for any undue control over the existing government, or any exclusive privileges or preferences in matters of commerce.” *

*The same sentiments were expressed in President Tyler’s message to Congress of December 30th, and in the Report of the Committee on Foreign Relations, written by John Quincy Adams.

Success of the Embassy in Europe—The king’s envoys proceeded to London, where they had been preceded by the Sir George Simpson, and had an interview with the Earl of Aberdeen, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, on the 22d of February, 1843.

they had been preceded by the Sir George Simpson, and had an interview with the Earl of Aberdeen, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, on the 22d of February, 1843.

Lord Aberdeen at first declined to receive them as ministers from an independent state, or to negotiate a treaty, alleging that the king did not govern, but that he was “exclusively under the influence of Americans to the detriment of British interests,” and would not admit that the government of the United States had yet fully recognized the independence of the islands.

Sir George and Mr. Richards did not, however, lose heart, but went on to Brussels March 8th, by a previous arrangement made with Mr. Brinsmade. While there, they had an interview with Leopold I., king of the Belgians, who received them with great courtesy, and promised to use his influence to obtain the recognition of Hawaiian independence. This influence was great, both from his eminent personal qualities and from his close relationship to the royal families of England and France.

Encouraged by this pledge, the envoys proceeded to Paris, where, on the 17th, M. Guizot, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, received them in the kindest manner, and at once engaged, in behalf of France, to recognize the independence of the islands. He made the same statement to Lord Cowley, the British ambassador, on the 19th, and thus cleared the way for the embassy in England.

They immediately returned to London, where Sir George had a long interview with Lord Aberdeen on the 25th, in which he explained the actual state of affairs at the islands, and received an assurance that Mr. Charlton would be removed. On the 1st of April, 1843, the Earl of Aberdeen formally replied to the king’s commissioners, declaring that “Her Majesty’s Government are willing and have determined to recognize the independence of the Sandwich Islands under their present sovereign,” but insisting on the perfect equality of all foreigners in the islands before the law, and adding that grave complaints had been received from British subjects of undue rigor exercised toward them, and improper partiality toward others in the administration of justice. Sir George Simpson left for Canada April 3d, 1843.

Recognition of the Independence of the Islands—Lord Aberdeen, on the 13th of June, assured the Hawaiian envoys that “Her Majesty’s government had no intention to retain possession of the Sandwich Islands,” and a similar declaration was made to the governments of France and the United States.

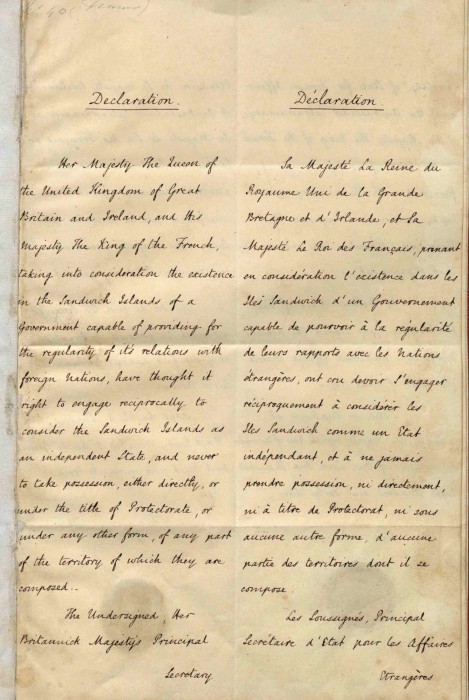

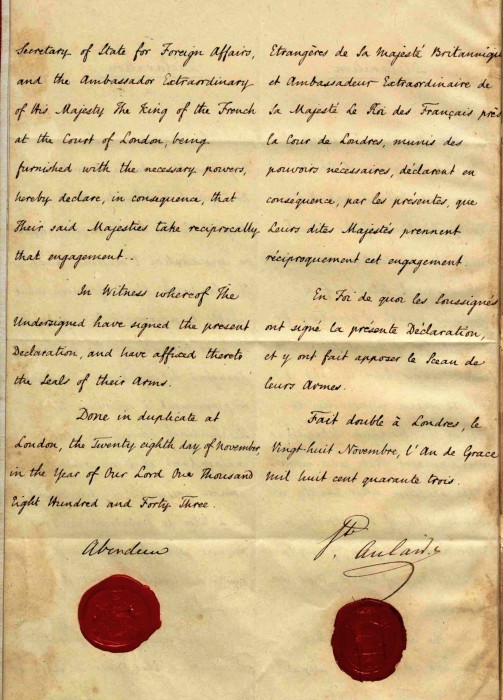

At length, on the 28th of November, 1843, the two governments of France and England united in a joint declaration to the effect that “Her Majesty, the queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and His Majesty, the king of the French, taking into consideration the existence in the Sandwich Islands of a government capable of providing for the regularity of its relations with foreign nations have thought it right to engage reciprocally to consider the Sandwich Islands as an independent state, and never to take possession, either directly or under the title of a protectorate, or under any other form, of any part of the territory of which they are composed…”

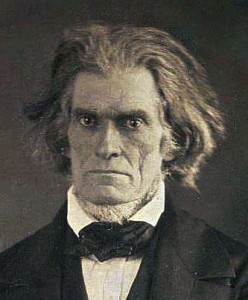

This was the final act by which the Hawaiian Kingdom was admitted within the pale of civilized nations. Finding that nothing more could be accomplished for the present in Paris, Messrs. Richards and Haalilio returned to the United States in the spring of 1844. On the 6th of July they received a dispatch from Mr. J.C. Calhoun, the Secretary of State, informing them that the President regarded the statement of Mr. Webster and the appointment of a commissioner “as a full recognition on the part of the United States of the independence of the Hawaiian Government.”

This was the final act by which the Hawaiian Kingdom was admitted within the pale of civilized nations. Finding that nothing more could be accomplished for the present in Paris, Messrs. Richards and Haalilio returned to the United States in the spring of 1844. On the 6th of July they received a dispatch from Mr. J.C. Calhoun, the Secretary of State, informing them that the President regarded the statement of Mr. Webster and the appointment of a commissioner “as a full recognition on the part of the United States of the independence of the Hawaiian Government.”

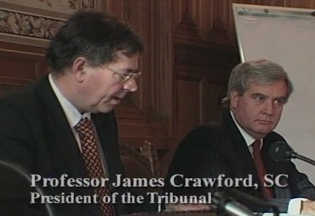

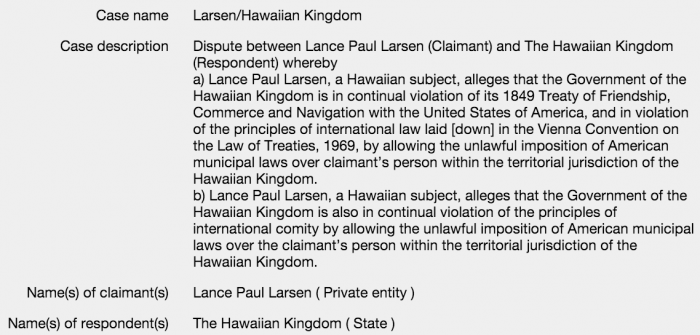

As part of the International Bureau’s due diligence into the status of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State under international law, the PCA’s Secretary General Van Den Hout made a formal recommendation to David Keanu Sai, Agent for the Hawaiian Government, to provide a formal invitation to the United States to join in the arbitration proceedings. This would have one of three outcomes—first, the United States would dispute the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State and the PCA would terminate the proceedings, second, it could join the arbitration in order to answer Larsen’s allegations of violating his rights that led to his incarceration, or, third, it could refuse to join in the arbitration, but allow it to go forward.

As part of the International Bureau’s due diligence into the status of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State under international law, the PCA’s Secretary General Van Den Hout made a formal recommendation to David Keanu Sai, Agent for the Hawaiian Government, to provide a formal invitation to the United States to join in the arbitration proceedings. This would have one of three outcomes—first, the United States would dispute the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State and the PCA would terminate the proceedings, second, it could join the arbitration in order to answer Larsen’s allegations of violating his rights that led to his incarceration, or, third, it could refuse to join in the arbitration, but allow it to go forward. In a conference call held in Washington, D.C., on March 3, 2000,

In a conference call held in Washington, D.C., on March 3, 2000,  between Mr. John Crook, United States Assistant Legal Adviser for United Nations Affairs, Ms. Parks and Mr. Sai, the United States was formally invited to join in the arbitration. It wasn’t until a couple of weeks later that the United States Embassy in The Hague notified the PCA that the United States will not join in the arbitration, but asked permission of the Hawaiian Government and Mr. Larsen’s attorney to have access to all pleadings, transcripts and records. The United States took the third option and did not deny the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State.

between Mr. John Crook, United States Assistant Legal Adviser for United Nations Affairs, Ms. Parks and Mr. Sai, the United States was formally invited to join in the arbitration. It wasn’t until a couple of weeks later that the United States Embassy in The Hague notified the PCA that the United States will not join in the arbitration, but asked permission of the Hawaiian Government and Mr. Larsen’s attorney to have access to all pleadings, transcripts and records. The United States took the third option and did not deny the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State.

After written pleadings were submitted, oral hearings were held at The Hague on December 7, 8, and 11, 2000, and the Arbitration Award was filed with the PCA on February 5, 2001. The court concluded that the United States was a necessary third party and without their participation in the arbitration proceedings, Mr. Larsen’s allegations of negligence against the Hawaiian Government could not move forward.

After written pleadings were submitted, oral hearings were held at The Hague on December 7, 8, and 11, 2000, and the Arbitration Award was filed with the PCA on February 5, 2001. The court concluded that the United States was a necessary third party and without their participation in the arbitration proceedings, Mr. Larsen’s allegations of negligence against the Hawaiian Government could not move forward.