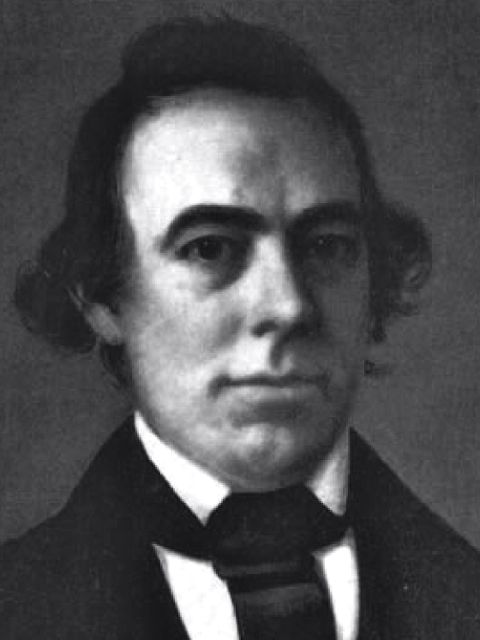

Below is a reprint of an article published in the Polynesian newspaper in 1845. The author is William Richards being one of the commissioners along with Timoteo Ha‘alilio and Sir George Simpson who were commissioned by King Kamehameha III with the purpose of securing the recognition of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State from Great Britain, France and the United States. Of the three, Ha‘alilio did not survive. He passed away on the ship The Montreal on his way home after departing Hawai‘i in 1842.

Below is a reprint of an article published in the Polynesian newspaper in 1845. The author is William Richards being one of the commissioners along with Timoteo Ha‘alilio and Sir George Simpson who were commissioned by King Kamehameha III with the purpose of securing the recognition of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State from Great Britain, France and the United States. Of the three, Ha‘alilio did not survive. He passed away on the ship The Montreal on his way home after departing Hawai‘i in 1842.

THE POLYNESIAN.

OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE HAWAIIAN GOVERNMENT.

HONOLULU, SATURDAY, MARCH 29, 1845.

The Montreal, from Boston, arrived off our harbor on Sunday last, at day break. Her ensign was noticed to be half-mast, and various conjectures began to circulate through the town, when William Richards, Esq., H.H.M.’s Commissioner to the U. States and Europe, whose arrival has been so long and anxiously awaited, landed and proceeded directly to the palace, where he immediately made known to their Majesties the melancholy news of the death of his fellow Commissioner, Mr. T. Haalilio, who died at sea on the 3d Dec. ult. The sad intelligence soon spread over the place; the flags of the men of war, merchant vessels, the consulates, batteries and other places, were immediately lowered to half-mast as a general expression of sympathy at the nation’s loss. Great hopes had been entertained both among Hawaiians and foreigners, of the good results that would ensue to the kingdom from the addition to its councils of one of so intelligent a mind, stored as it was with the fruits of observant travel, and the advantages derived from long and familiar intercourse in the best circles of Europe and the United States. A numerous band of personal friends to whom he had been endeared from his earliest intercourse by his sincerity of manners and peculiarly affectionate deportment, were earnestly looking to welcome him home. But above all, their Majesties, his intimate friends, the Governors, the other high chiefs and his widowed mother were awaiting his arrival with an earnestness of hope that the deepest affections of the heart can alone produce. The last tidings from him had been those of health. He was then soon to embark, and his speedy arrival to the shores and friends he loved so well, was anticipated without a doubt. So unexpected a termination of his existence, after having escaped the dangers of long and trying journe[y]s and voyagings, while as it were, on the very eve of again treading his native land, brings with it more than common anguish. It is not for us to life the veil and expose the scene which ensued at the palace upon the communication of the tidings. The whole court were there assembled. Those who had been suddenly deprived of their choicest hope when on the eve of its full indulgence, can alone estimate the bereavement.

The Montreal, from Boston, arrived off our harbor on Sunday last, at day break. Her ensign was noticed to be half-mast, and various conjectures began to circulate through the town, when William Richards, Esq., H.H.M.’s Commissioner to the U. States and Europe, whose arrival has been so long and anxiously awaited, landed and proceeded directly to the palace, where he immediately made known to their Majesties the melancholy news of the death of his fellow Commissioner, Mr. T. Haalilio, who died at sea on the 3d Dec. ult. The sad intelligence soon spread over the place; the flags of the men of war, merchant vessels, the consulates, batteries and other places, were immediately lowered to half-mast as a general expression of sympathy at the nation’s loss. Great hopes had been entertained both among Hawaiians and foreigners, of the good results that would ensue to the kingdom from the addition to its councils of one of so intelligent a mind, stored as it was with the fruits of observant travel, and the advantages derived from long and familiar intercourse in the best circles of Europe and the United States. A numerous band of personal friends to whom he had been endeared from his earliest intercourse by his sincerity of manners and peculiarly affectionate deportment, were earnestly looking to welcome him home. But above all, their Majesties, his intimate friends, the Governors, the other high chiefs and his widowed mother were awaiting his arrival with an earnestness of hope that the deepest affections of the heart can alone produce. The last tidings from him had been those of health. He was then soon to embark, and his speedy arrival to the shores and friends he loved so well, was anticipated without a doubt. So unexpected a termination of his existence, after having escaped the dangers of long and trying journe[y]s and voyagings, while as it were, on the very eve of again treading his native land, brings with it more than common anguish. It is not for us to life the veil and expose the scene which ensued at the palace upon the communication of the tidings. The whole court were there assembled. Those who had been suddenly deprived of their choicest hope when on the eve of its full indulgence, can alone estimate the bereavement.

It is satisfactory to know that every attention affection or sympathy could suggest, was afforded the deceased. Previous to our own departure from the United States, we were a witness to the deep interest and respect which Mr. Haalilio received in the refined society of Boston. But our already crowded columns will not allow us further to dilate. From Mr. Richards he received in all stages of his journey the most unremitting care, and towards the close of his life he was ever at his bed-side. Our readers will be able to glean from the brief memoir which follows this, prepared by Mr. R. some further insight into his life and untimely end. We say untimely, but man seeeth not as god seeeth.

Haalilio was born in 1808, at Koolau; Oahu. His parents were of respectable rank, and much esteemed. His father died while he was quite young, and his widowed mother subsequently married the Governor of Molokai, an island depend[e]nt on the Governor of Maui. After this death, she retained the authority of the island, and acted as Governess for the period of some fifteen years.

At the age of about eight years, Haalilio removed to Hilo on Hawaii, where he was adopted in the family, and became one of the playmates, of the young prince, now King of the Islands. He traveled round to different parts of the Islands with the prince, conforming to the various heathenish rites which were then in vogue. From that period he remained one of the most intimate companions and associates of the King.

At the age of about thirteen, he commenced learning to read, and was a pleasant pupil and made great proficiency. There were then no regularly established schools, and he was a private pupil of Mrs. Bingham. He learned to read English as well as Hawaiian, though at that period he did not understand what he read. He was taught arithmetic and penmanship by Mr. Bingham, and was early employed by the King to do his writing–not as an official secretary, but as an amanuensis or clerk. As be advanced in years he had various duties and employments assigned him, requiring skill and responsibility. Being associated with the King, he was always received into society with him, and thus enjoyed various advantages which he prized very much and improved in the best manner. He thus became acquainted with the usages of good society which he never failed to adopt as fast as he became acquainted with them.

To him also the King committed the charge of his private purse, which he held till the time of his embarkation. It thus became his duty to make most of the purchases required by the King, and he thereby had opportunity to become acquainted with the detail of mercantile business, of which he acquired a very commendable knowledge. His habits of business were many of them worthy of imitation even by the most enlightened. He was in a good degree systematic, and was extremely careful of every thing committed to this charge.

Besides acquaintance with mercantile transactions, he also acquired a very full knowledge of the political relations of the country. He was a strenuous advocate for a constitutional and representative government, and aided not a little in effecting those changes by which the rights of the lower classes have been secured. He was well acquainted with the practical influence of the former system of government, and considered a change necessary to the welfare of the nation.

The King and Chiefs could not fail to see the real value of such a man, and they therefore promoted him to offices to which his birth would not, according to the old system, have entitled him. He was properly the Lieutenant-Governor of the Island of Oahu, and regularly acted as Governor during the absence of the incumbent. It was expected also that he would succeed the present Governor in his office, had he outlived him. He was also elected a member of the council of Nobles, and materially aided that body in their deliberations. At the last meeting of the Legislature previous to his leaving the country, he was chosen President of the Treasury Board, and thus in a considerable degree he had control of the finances of the nation.

In the month of April, 1842, he was appointed a joint Commissioner with Mr. Richards, to the Courts of the U.S.A, England and France. He embarked on the 18th of July following on board the sch. Shaw, and arrived at Mazatlan Sept. 1st. While on the passage he often talked of home and friends with a tenderness and emotion that showed a high degree of sensibility and refinement. On his arrival at port, he was received with great hospitality. In crossing Mexico, he was deeply interested in noticing the peculiarities of the scenery, the character of the people, and the natural history of the country. Nothing escaped his observation; and the correctness and good sense of his remarks, rendered him not merely a pleasant but a profitable companion. After spending a fortnight at Vera Cruz, he was by the politeness of Capt. Newton received on board the U.S. steamer Missouri, about to sail to the mouth of the Mississippi. On board that vessel he had the company of Mr. Mayer, the U.S. Sec. of Legation at Mexico; and Mr. Southall, Bearer of Despatches, with whom he proceeded to New Orleans, and then by the mail route to Washington, where he arrived on the 3d of Dec. The results of his embassy there, are already before the public. After spending a month at Washington, and having accomplished the main objects of embassy there, he proceeded to the north, making a short stay of only two days in New York; but on his arrival in the western part of Massachusetts, was attacked by a severe cold, brought on by the inclemencies of the weather, followed by a change in the thermometer of about sixty degrees in twenty-four hours. Here was probably laid the foundation of that disease by which his short but eventful life has been so afflictingly closed.

He however so far recovered that he embarked for England in the steamer Caledonia, on the 2d of Feb. 1843, and arrived in London on the 18th of the same month, and was apparently at that time in perfect health. He immediately entered on the business of his embassy, and before six weeks had expired, had the happiness to receive from the Earl of Aberdeen, the official and solemn declaration that “Her Majesty’s Government are willing and have determined to recognize the independence of the Sandwich Islands under their present Sovereign.” He was also received and treated with high consideration by all persons of distinction to whom he was introduced. The Hon. Mr. Ellis; Sir Henry Pelly; the Earl of Selkirk; the Duke and Duchess of Sommerset; Sir Augustus d’Este, cousin of the Queen; the Lord Chamberlain; and the Mayor of London, were among the number of those from whom he received special attentions. While in Europe, as well as in the U.S.A., he made it a special business to visit and examine all objects of public interest which claim the attention of the traveller. The various manufacturing establishments, the museums, the hospitals, the prisons, the great works of architecture, the ancient palaces and cathedrals, the bridges, dockyards, and mausoleums of the dead,–the public schools and institutions of charity, and various religious establishments; all received his attention, and produced an influence on his mind which it was most interesting to witness.

After accomplishing the object of his embassy to England, he proceeded to France, where he was received in the same respectful manner as in England, and after carious delays, finally succeeded in obtaining from the French Government, not only a recognition of independence, but also a mutual guarantee from England and France that that independence should be respected. In Belgium he was honored with an interview with the King Leopold, and received the same recognition of independence as had been obtained from the other nations. The persons from whom he received special attentions in France, were M. Guizot; Count and Countess Gasparin; the Lafayette family; Count de la Bonde; Duke de Caze; Admiral Baudin; Duke de Broglie; the Baron Champloies; Count Pellet; Count Salvandy; M. de Toqueville; Lady Elgin, and others. In all the society he visited, he never failed to secure entire respect.

After spending about fifteen months in Europe, he returned to the U. S. A. in the Britannia, and reached Boston on the 18th of May ult. It should have been mentioned however, that while in Paris in June 1843, he was affected by a cold, rheumatic pains and coughs, which soon yielded to medical treatment, and his health again became good. But in Jan. last he was more seriously afflicted, being confined to his room, and mostly to his bed, for a period of more than four weeks. At this time his cough was very severe, the soreness of his breast great, and his symptoms in many respects threatening. He soon recovered, however, and on his arrival in the U.S.A. was in good health. He spent most of the summer in traveling. He visited Washington again, and proceeded to Wheeling, Va.; thence to Pittsburg, and on to Cleveland, Ohio, and down the lake to Buffalo, and Niagara Falls; thence through lake Ontario to Syracuse, Albany, and down the Hudson to New York.

He subsequently returned to Albany, and thence on through White-Hall and lake Champlain to Montreal in Canada. He returned through the interior of Vermont and New Hampshire to Boston, where he spent a few weeks, visiting the various places of importance in that vicinity; Cambridge, Charleston, Roxbury, Plymouth, Quincey, Newburyport, Andover, Lowell, and other places. It is impossible to describe the interest that he took in these visits, or the profit he appeared to derive from them.

But it is now time to revert to another trait in his character; I mean his religious views and affections.

But a few days after we embarked from the Islands, as he opened his trunk, I noticed the Hawaiian Bible lying in it, which he took and began to read. This was the commencement of a practice which he followed till his frame was too weak to follow it longer. Few if any days passed except when actually traveling or employed in important business, in which he was not seen reading that precious book. A few days previous to his death he told me he had read it twice through in course since he left the Islands, beside all his incidental reading. Besides the Scriptures, he read much in other books of a religious character, though his reading was by no means confined to nor was it principally religious books. After exhausting his Hawaiian library, he read considerable in English.

To show his feelings on the subject of prayer, I will mention, that after traveling in Mexico for a number of successive days, and every night being in the midst of company and bustle, without a possibility of retirement, we at last arrived at the hospitable dwelling of an E[n]glish gentlemen, who at bed time conducted us to a retired and pleasant chamber. Our host had scarcely left us when Haalilio turned his eyes and surveying the room for a moment said with an expressive countenance, “We have at last found a place where we can pray.” He showed that he was not a stranger to prayer. The apparent humility with which he made confession of sins, the fervency with which he asked Divine aid in the business of our embassy, and the tenderness with which he implored the blessing of Heaven on his friends and countrymen, early led me to feel that prayer with him was not a mere empty form. From that time down to the last sad hour of his life, I had evidence that in a good degree he kept the commandment.—”Be instant in prayer.” Many and many a night when he supposed me to be asleep, have I heard his voice or rather whisper, laying open his heart before his Maker.

By the deep interest which he manifested in a faithful observance of the Sabbath, he showed that he was not regardless of the Divine requisitions. While in France and Belgium, never a Sabbath passed in which he did not express his astonishment at the public, open, and constant violation of God’s holy day. On the contrary, while in England and the U. S. A. he as often expressed his admiration as he witnessed the stillness of the streets and the multitudes of those who thronged the house of God.

The illness which terminated his life commenced on the 13th of Sept. last, while in Brooklyn, New York. At first he merely complained of slight rheumatic pain, and indisposition to exercise. At the end of a week it suddenly increased and exhibited the usual marks of a cold. Medicine was promptly administered, and after keeping his room for a week, he was so much better as to leave it and take exercise in open air. But as he recovered from his rheumatism, I noticed an increase of cough, especially in the morning. To this I called the attention of the physician. He considered the cough as merely symptomatic, and giving a common cough mixture, predicted its early removal. On the 16th of Oct. he removed to Boston, and the first physicians of the city were immediately called. They pronounced his lungs sound, and his disease to be a slow fever. On the third day however, their opinion changed, and they thought his lungs affected, but not seriously. At their advice, and the advice of numerous other friends, he was removed to the Massachusetts Hospital, where every thing was done which science could prescribe, or medicine effect. But his disease made rapid strides, and his flesh wasted fast.

During the whole period of his illness he took a rational and correct view of his own case. He early discovered the danger of his symptoms, yet never appeared alarmed, nor renounced the hope of recovery, until a few days previous to his death. And in all circumstances he appeared calm and resigned, saying, “Father, not my will but thine be done.” While at the Hospital, I heard him whisper this in prayer, at the still hour of midnight, while he supposed I was asleep. On one occasion, I noticed him wiping the tear from his cheek, and went to his bedside to sympathi[z]e and comfort him. He immediately said, “I was not weeping for myself, but for you.” I inquired if he was not anxious to live and reach the Islands. He replied, “Not on my own account. I [s]hould indeed be glad to tell the chiefs and people what I have seen, and in their presence dedicate myself to God; but respecting myself I do not feel anxious.” The great subjects of those prayers which I overheard were confessions of sin, pleading for relief from suffering, imploring blessings on his mother, on the King and on his countrymen. He prayed also that he might live to reach the Islands; but this prayer was usually conditional, and ended with “Aia no ia oe”–it is with thee, or, they will be done. Before he came on board, he dictated a few affecting sentences to the King and Chiefs.–The second Sabbath we were at sea, he became convinced that he could not live, and gave farther charge to be delivered to the King and Chiefs. He expressed also a wish to be bapti[z]ed. On the evening of that Sabbath, while speaking of his pain and sufferings and immediate prospect of death, he added, “But this is the happiest day of my life. My work is done. I am ready to go.” He continued in the same general state of mind to the time of his departure. During the last few hours of his life he prayed several times, but I only understood one important sentence, which was nearly like this: “My Father, thou hast not granted my desire, once more to see the land of my birth, and my friends there, but do not, I entreat thee, refuse my request to see they kingdom, and my friends who are dwelling with thee.” At about four o’clock he slapped his arms about my neck, pulled my face down to his, and kissed me, then said, “Heaha ke koe?” What further remains? I replied, “Eternal life in Heaven, if you believe in Jesus. He will be your King, and angels will be your associates; there will be no groans there, no parting, no weakness, no anguish or pain, and no sin.” He replied, “That is plain; I understand it well; but I have no painful anxiety on that subject, and it was not to that that my question related. What further have I to do here?” I replied, “It is with the Lord; I know not: all your charges to me I have put down in writing, and shall faithfully deliver them according to your directions.” A little while after, he reached out his hand, took hold of mine and shook it with a smile, and then let go. At a quarter before seven, I perceived his again in prayer; but his voice soon died away, and I perceived that his end was near; and at seven, his spirit took its flight.

on business, and became interested in the native people and their government. After a candid examination of the controversies existing between their own countrymen and the Hawaiian Government, they became convinced that the latter had been unjustly accused. Sir George offered to loan the government ten thousand pounds in cash, and advised the king to send commissioners to the United States and Europe with full power to negotiate new treaties, and to obtain a

on business, and became interested in the native people and their government. After a candid examination of the controversies existing between their own countrymen and the Hawaiian Government, they became convinced that the latter had been unjustly accused. Sir George offered to loan the government ten thousand pounds in cash, and advised the king to send commissioners to the United States and Europe with full power to negotiate new treaties, and to obtain a guarantee of the independence of the kingdom.

guarantee of the independence of the kingdom. Mr. Richards also received full power of attorney for the king. Sir George left for Alaska, whence he traveled through Siberia, arriving in England in November. Messrs. Richards and Haalilio sailed July 8th, 1842, in a chartered schooner for Mazatlan, on their way to the United States*

Mr. Richards also received full power of attorney for the king. Sir George left for Alaska, whence he traveled through Siberia, arriving in England in November. Messrs. Richards and Haalilio sailed July 8th, 1842, in a chartered schooner for Mazatlan, on their way to the United States* Secretary of State, from whom they received an official letter December 19th, 1842, which recognized the independence of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and declared, “as the sense of the government of the United States, that the government of the Sandwich Islands ought to be respected; that no power ought to take possession of the islands, either as a conquest or for the purpose of the colonization; and that no power ought to seek for any undue control over the existing government, or any exclusive privileges or preferences in matters of commerce.” *

Secretary of State, from whom they received an official letter December 19th, 1842, which recognized the independence of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and declared, “as the sense of the government of the United States, that the government of the Sandwich Islands ought to be respected; that no power ought to take possession of the islands, either as a conquest or for the purpose of the colonization; and that no power ought to seek for any undue control over the existing government, or any exclusive privileges or preferences in matters of commerce.” * they had been preceded by the Sir George Simpson, and had an interview with the Earl of Aberdeen, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, on the 22d of February, 1843.

they had been preceded by the Sir George Simpson, and had an interview with the Earl of Aberdeen, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, on the 22d of February, 1843. This was the final act by which the Hawaiian Kingdom was admitted within the pale of civilized nations. Finding that nothing more could be accomplished for the present in Paris, Messrs. Richards and Haalilio returned to the United States in the spring of 1844. On the 6th of July they received a dispatch from Mr. J.C. Calhoun, the Secretary of State, informing them that the President regarded the statement of Mr. Webster and the appointment of a commissioner “as a full recognition on the part of the United States of the independence of the Hawaiian Government.”

This was the final act by which the Hawaiian Kingdom was admitted within the pale of civilized nations. Finding that nothing more could be accomplished for the present in Paris, Messrs. Richards and Haalilio returned to the United States in the spring of 1844. On the 6th of July they received a dispatch from Mr. J.C. Calhoun, the Secretary of State, informing them that the President regarded the statement of Mr. Webster and the appointment of a commissioner “as a full recognition on the part of the United States of the independence of the Hawaiian Government.”

Below is a reprint of an article published in the Polynesian newspaper in 1845. The author is William Richards being one of the commissioners along with Timoteo Ha‘alilio and Sir George Simpson who were commissioned by King Kamehameha III with the purpose of securing the recognition of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State from Great Britain, France and the United States. Of the three, Ha‘alilio did not survive. He passed away on the ship The Montreal on his way home after departing Hawai‘i in 1842.

Below is a reprint of an article published in the Polynesian newspaper in 1845. The author is William Richards being one of the commissioners along with Timoteo Ha‘alilio and Sir George Simpson who were commissioned by King Kamehameha III with the purpose of securing the recognition of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State from Great Britain, France and the United States. Of the three, Ha‘alilio did not survive. He passed away on the ship The Montreal on his way home after departing Hawai‘i in 1842. The Montreal, from Boston, arrived off our harbor on Sunday last, at day break. Her ensign was noticed to be half-mast, and various conjectures began to circulate through the town, when William Richards, Esq., H.H.M.’s Commissioner to the U. States and Europe, whose arrival has been so long and anxiously awaited, landed and proceeded directly to the palace, where he immediately made known to their Majesties the melancholy news of the death of his fellow Commissioner, Mr. T. Haalilio, who died at sea on the 3d Dec. ult. The sad intelligence soon spread over the place; the flags of the men of war, merchant vessels, the consulates, batteries and other places, were immediately lowered to half-mast as a general expression of sympathy at the nation’s loss. Great hopes had been entertained both among Hawaiians and foreigners, of the good results that would ensue to the kingdom from the addition to its councils of one of so intelligent a mind, stored as it was with the fruits of observant travel, and the advantages derived from long and familiar intercourse in the best circles of Europe and the United States. A numerous band of personal friends to whom he had been endeared from his earliest intercourse by his sincerity of manners and peculiarly affectionate deportment, were earnestly looking to welcome him home. But above all, their Majesties, his intimate friends, the Governors, the other high chiefs and his widowed mother were awaiting his arrival with an earnestness of hope that the deepest affections of the heart can alone produce. The last tidings from him had been those of health. He was then soon to embark, and his speedy arrival to the shores and friends he loved so well, was anticipated without a doubt. So unexpected a termination of his existence, after having escaped the dangers of long and trying journe[y]s and voyagings, while as it were, on the very eve of again treading his native land, brings with it more than common anguish. It is not for us to life the veil and expose the scene which ensued at the palace upon the communication of the tidings. The whole court were there assembled. Those who had been suddenly deprived of their choicest hope when on the eve of its full indulgence, can alone estimate the bereavement.

The Montreal, from Boston, arrived off our harbor on Sunday last, at day break. Her ensign was noticed to be half-mast, and various conjectures began to circulate through the town, when William Richards, Esq., H.H.M.’s Commissioner to the U. States and Europe, whose arrival has been so long and anxiously awaited, landed and proceeded directly to the palace, where he immediately made known to their Majesties the melancholy news of the death of his fellow Commissioner, Mr. T. Haalilio, who died at sea on the 3d Dec. ult. The sad intelligence soon spread over the place; the flags of the men of war, merchant vessels, the consulates, batteries and other places, were immediately lowered to half-mast as a general expression of sympathy at the nation’s loss. Great hopes had been entertained both among Hawaiians and foreigners, of the good results that would ensue to the kingdom from the addition to its councils of one of so intelligent a mind, stored as it was with the fruits of observant travel, and the advantages derived from long and familiar intercourse in the best circles of Europe and the United States. A numerous band of personal friends to whom he had been endeared from his earliest intercourse by his sincerity of manners and peculiarly affectionate deportment, were earnestly looking to welcome him home. But above all, their Majesties, his intimate friends, the Governors, the other high chiefs and his widowed mother were awaiting his arrival with an earnestness of hope that the deepest affections of the heart can alone produce. The last tidings from him had been those of health. He was then soon to embark, and his speedy arrival to the shores and friends he loved so well, was anticipated without a doubt. So unexpected a termination of his existence, after having escaped the dangers of long and trying journe[y]s and voyagings, while as it were, on the very eve of again treading his native land, brings with it more than common anguish. It is not for us to life the veil and expose the scene which ensued at the palace upon the communication of the tidings. The whole court were there assembled. Those who had been suddenly deprived of their choicest hope when on the eve of its full indulgence, can alone estimate the bereavement.