Because people “believe” that the Hawaiian Islands are a part of the United States as the 50th State of the American Union, it does not mean that it is true, especially from a “legal” standpoint. As Abraham Lincoln once asked, how many legs does a calf have if you call its tail a leg? Five, the questioner responded. Lincoln said no. Calling a calf’s tail a leg doesn’t make it a leg.

When the Hawaiian Kingdom filed its Notice of Appeal with the Clerk of the United States District Court for the District of Hawai‘i on April 24, 2022, it specifically stated that the Hawaiian Kingdom was appealing to a competent Court of Appeals to be hereafter established by the United States as an Occupying Power here in the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom. It was the Clerk that transferred the Notice of Appeal to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco, and not the Hawaiian Kingdom.

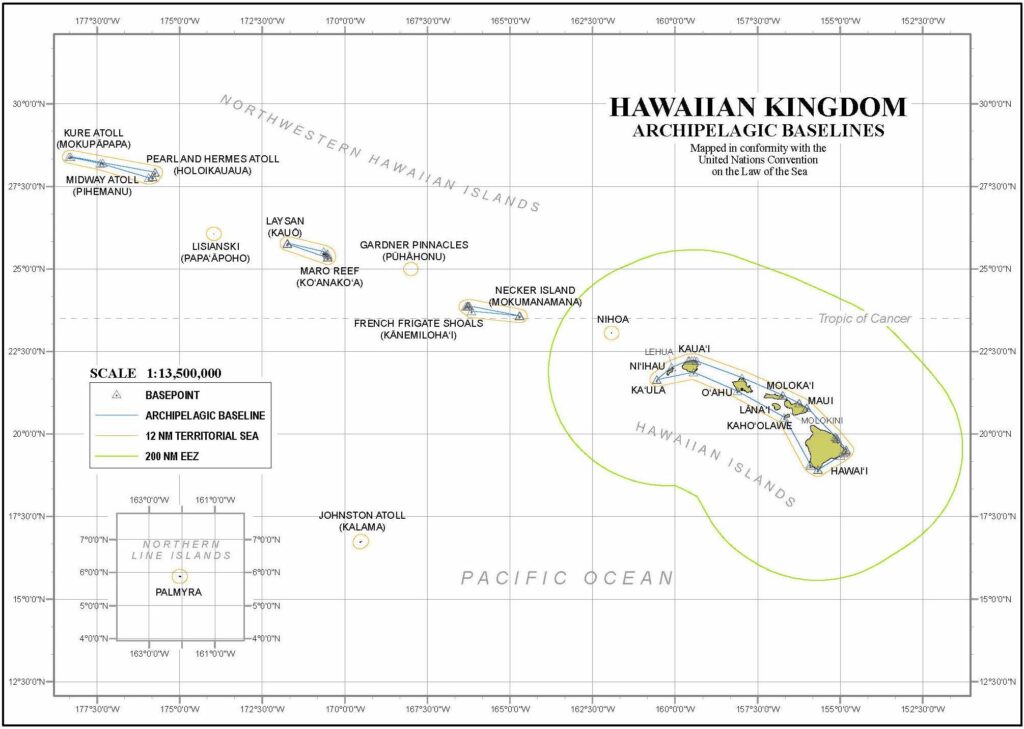

The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals can only hear appeals that come from one of the District Courts within its circuit. These District Courts are located within the United States. The District Court in Honolulu is not situated in the territory of the United States but rather in the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

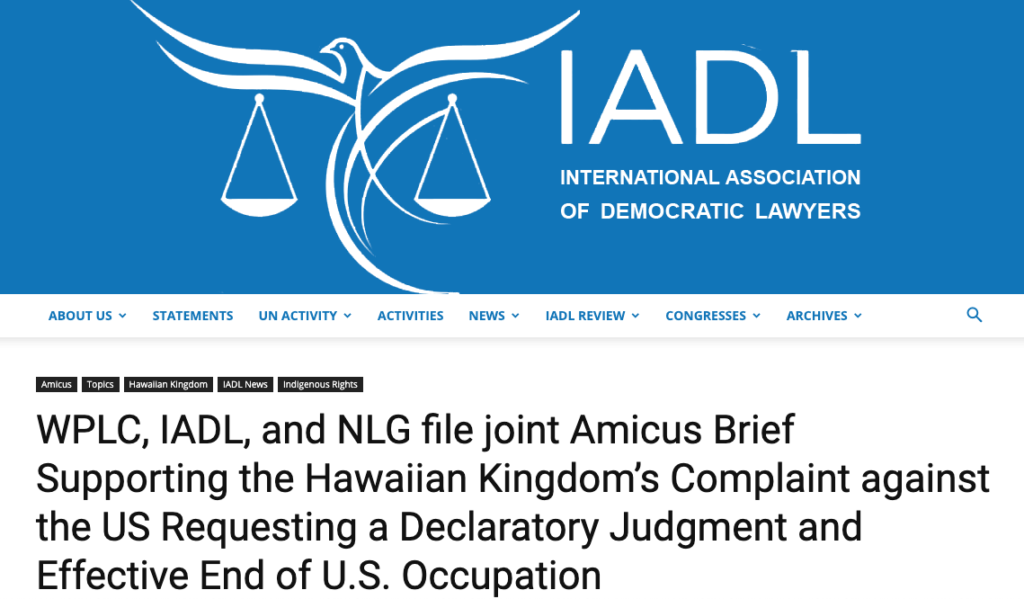

The Hawaiian Kingdom drew attention to the illegality of the District Court in its Amended Complaint that was filed on August 11, 2021, which led to an amicus brief filed on October 6, 2011, by the International Association of Democratic Lawyers, the National Lawyers Guild, and the Water Protectors Legal Collective as to why the District Court had to transform from an Article III Court to an Article II Occupation Court because it is in occupied territory of a foreign State—the Hawaiian Kingdom.

The Notice of Appeal was filed in response to District Court Judge Leslie Kobayashi’s ruling on a motion to dismiss from the Swedish Honorary Consul without first transforming into an Article II Occupation Court. Judge Kobayashi stated that she didn’t need to transform into an Article II Occupation Court because in seventeen previous cases that came before the District Court of Hawai‘i since 1993, the federal judges in these cases all ruled that the Hawaiian Kingdom does not exist as a State.

Her reasoning was flawed so the Hawaiian Kingdom requested Judge Kobayashi to reconsider her decision in light of international law, but she responded that the Hawaiian Kingdom just disagrees with her decision. This resulted in the filing of the Notice of Appeal to an Article II Occupation Appellate Court to be hereafter established by the United States as an Occupying State. The Hawaiian Kingdom filed the appeal so that the records of its case can be preserved for future proceedings. Kobayashi did not dismiss the case.

On May 3, 2022, the Clerk of the Ninth Circuit filed an Order that stated, “Within 21 days after the date of this order, appellant shall either move for voluntary dismissal of the appeal or show cause why it should not be dismissed for lack of jurisdiction.” In response to this Order, the Hawaiian Kingdom today, May 20th, filed a Motion to Dismiss for Forum Non Conveniens. Because the Ninth Circuit is a bona fide Appellate Court in the United States, it allows the Hawaiian Kingdom to file this type of a Motion to Dismiss and can fully argue its case. Normally defendants named in an appeal would file, if appropriate, a Motion to Dismiss for Forum Non Conveniens, and not the plaintiff in an appeal to dismiss its appeal. This case, however, is a truly unique situation.

This type of motion is filed when an appeals court in a foreign country should be hearing the appeal, and not, in this case, the Ninth Circuit. The appropriate court would be an Article II Occupation Appellate Court in the Hawaiian Kingdom, which hasn’t been established yet. In its Motion to Dismiss, the Hawaiian Kingdom explained:

Under international law there is a presumption that an established sovereign and independent State, being a subject of international law, continues to exist despite the overthrow of its government. See Professor Quincy Wright, “The Status of Germany and the Peace Proclamation,” 46, no. 2 American Journal of International Law 299, 307 (April 1952) (“[i]nternational law distinguishes between a government and the state it governs. This distinction makes it clear that the extinction of the Nazi Government and the temporary absence of any German Government did not necessarily mean that Germany as a state ceased to exist”); see also Professor Yejoon Rim, “State Continuity in the Absence of Government: The Underlying Rationale in International Law,” 20(20) European Journal of International Law 1, 4 (2021) (the State continues “to exist even in the factual absence of government so long as the people entitled to reconstruct the government remain”). According to Professor Ian Brownlie, Principles of Public International Law, 109 (4th ed., 1990):

“Thus after the defeat of Nazi Germany in the Second World War the four major Allied powers assumed supreme power in Germany. The legal competence of the German state did not, however, disappear. What occurred is akin to legal representation or agency of necessity. The German state continued to exist, and, indeed, the legal basis of the occupation depended on its continued existence.”

Therefore, the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State is presumed to continue to exist despite its government being unlawfully overthrown by the Defendant Appellee UNITED STATES OF AMERICA’s military on January 17, 1893. As such, the District Court of Hawai‘i is not a properly constituted court in accordance with international humanitarian law, and, therefore, had to transform itself into an Article II Occupation Court.

If the U.S. District Court of Hawai‘i did not have jurisdiction or authority to rule in the case, the Ninth Circuit, as an appeals court, wouldn’t have authority as well. This is because the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist as a State despite the unlawful overthrow of its government by the United States military on January 17, 1893. This is not the State of Hawai‘i.

According to Judge James Crawford from the International Court of Justice, “there is a presumption that the State continues to exist, with its rights and obligations despite a period in which there is no effective government.” He also stated that “belligerent occupation does not affect the continuity of the State, even where there exists no government claiming to represent the occupied State.”

“If one were to speak about a presumption of continuity,” explains Professor Matthew Craven, “one would suppose that an obligation would lie upon the party opposing that continuity to establish the facts substantiating its rebuttal. The continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom, in other words, may be refuted only by reference to a valid demonstration of legal title, or sovereignty, on the part of the United States, absent of which the presumption remains.”

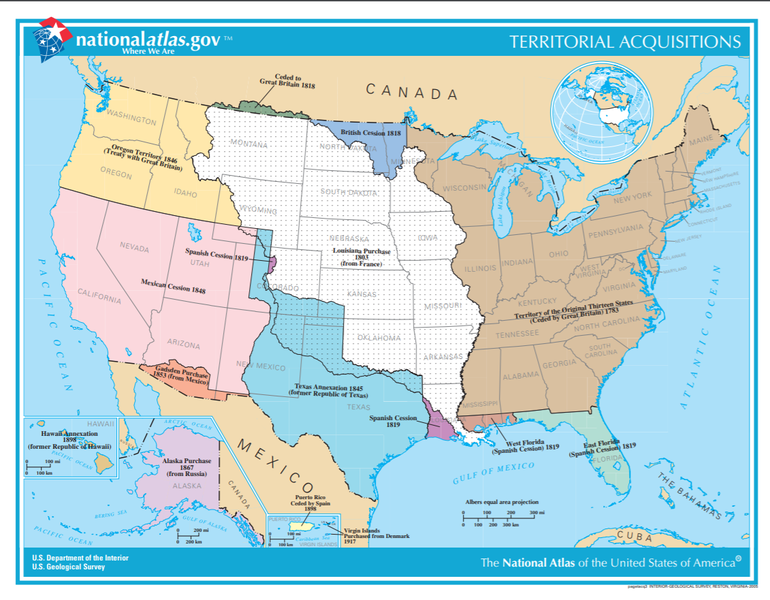

A legal title under international law would be a treaty between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States where the Hawaiian State would merge with the State of the United States called a treaty of cession. In other words, the question is not whether the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist, but rather can “the party opposing that continuity” establish factual evidence, i.e., treaty cession, that it “does not exist.” In the absence of the evidence that it “does not exist,” the Hawaiian Kingdom “continues to exist” as a State under international law.

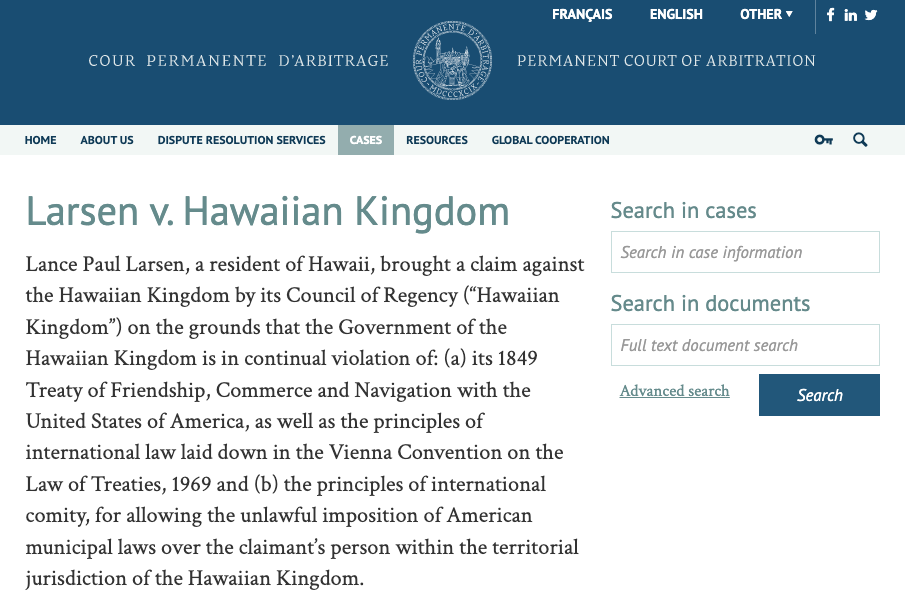

This is precisely why the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA), in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, acknowledged the presumption of the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State when the proceedings were initiated on November 8, 1999. The PCA could find no evidence under international law that the Hawaiian Kingdom “does not exist,” therefore, it continues to exist.

The “presumption of the continuity of a State” is similar to the “presumption of innocence.” A person on trial does not have the burden to prove their innocence. Rather, the prosecutor has to prove beyond all reasonable doubt that the person “is not” innocent. Without proof of guilt, the person remains innocent. In international law, a recognized sovereign and independent State does not have the burden to prove it continues be a State after its government was overthrown and subjected to being belligerently occupied for over a century. Rather, the party opposing the presumption has to prove with evidence under international law that the State was extinguished. Absent the evidence, the State continues to exist.

When the seventeen federal cases that ruled the Hawaiian Kingdom doesn’t exist as a State, it cited a precedent case in 1994 that was heard by the State of Hawai‘i Intermediate Court of Appeals called State of Hawai‘i v. Lorenzo. In the federal courts it is known as the “Lorenzo principle.” As the District Court in 2002 stated, in United States v. Goo:

Since the Intermediate Court of Appeals for the State of Hawaii’s decision in Hawaii v. Lorenzo, the courts in Hawaii have consistently adhered to the Lorenzo court’s statements that the Kingdom of Hawaii is not recognized as a sovereign state by either the United States or the State of Hawaii. See Lorenzo, 77 Haw. 219, 883 P.2d 641, 643 (Haw. App. 1994); see also State of Hawaii v. French, 77 Haw. 222, 883 P.2d 644, 649 (Haw. App. 1994) (stating that “presently there is no factual (or legal) basis for concluding that the [Hawaiian] Kingdom exists as a state in accordance with recognizing attributes of a state’s sovereign nature”) (quoting Lorenzo, 883 P.2d at 643). This court sees no reason why it should not adhere to the Lorenzo principle.

According to the Lorenzo principle, the burden of proof was on the defendants in the seventeen cases, and that these defendants did not provide evidence of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s existence as a State. In the 1994 Lorenzo decision, however, the Appellate Court did acknowledge that its “rationale is open to question in light of international law.” The federal judges in the seventeen cases were not correctly applying the Lorenzo principle with international law.

Because the presumption of State continuity is a rule of international law, the Lorenzo principle turns it into a rule of evidence that shifts the burden of proof away from the defendants to prove the Hawaiian Kingdom “exists” as a State, to those opposing the presumption of Hawaiian State continuity to prove that the Hawaiian Kingdom “does not exist” as a State under international law. The only evidence to show that the Hawaiian Kingdom “does not exist” is that there must be a treaty of cession where the Hawaiian Kingdom ceded itself to the United States. There exists no such treaty!

This is a radical shift of the burden of proof and not only were the seventeen federal cases wrongly decided, but every case that came before the federal courts in Hawai‘i since 1900 are all void because the United States did not extinguish the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State under international law before it created, by Congressional legislation, the so-called Territory of Hawai‘i in 1900 and the so-called State of Hawai‘i in 1959. This is why in the Lorenzo decision, the Appellate Court stated that the “illegal overthrow leaves open the question whether the present governance system should be recognized” under international law. This is not just federal court decisions since 1900, Territory of Hawai‘i court decisions since 1900, and State of Hawai‘i court decisions since 1959, but all decisions made by an illegal American government that span from unlawful taxation, business regulations to land titles.

In its Motion to Dismiss, the Hawaiian Kingdom is setting the stage for the United States, as a defendant in this case, to provide evidence that the Hawaiian Kingdom was extinguished as a State under international law. To do this, the Hawaiian Kingdom is invoking the Lorenzo principle, by applying international law, in order for the Ninth Circuit Court to schedule an evidentiary hearing that will compel the United States to provide the evidence of a treaty of cession and prove that the seventeen cases using the Lorenzo principle were “not in error.”

But here is the catch, for the United States to provide evidence is to directly acknowledge the presumption that the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist and that the United States federal government and the State of Hawai‘i are unlawful. This rule of international law was triggered on January 17, 1893.

As Sir Walter Scott wrote, “Oh what a tangled web we weave/When first we practice to deceive.”