#ProtectedPersonsHawaii

#WarCrimesHawaii

Monthly Archives: November 2018

National Holiday – Independence Day (November 28)

November 28th is the most important national holiday in the Hawaiian Kingdom. It is the day Great Britain and France formally recognized the Hawaiian Islands as an “independent state” in 1843, and has since been celebrated as “Independence Day,” which in the Hawaiian language is “La Ku‘oko‘a.” Here follows the story of this momentous event from the Hawaiian Kingdom Board of Education history textbook titled “A Brief History of the Hawaiian People” published in 1891.

**************************************

The First Embassy to Foreign Powers—In February, 1842, Sir George Simpson and Dr. McLaughlin, governors in the service of the Hudson Bay Company, arrived at Honolulu  on business, and became interested in the native people and their government. After a candid examination of the controversies existing between their own countrymen and the Hawaiian Government, they became convinced that the latter had been unjustly accused. Sir George offered to loan the government ten thousand pounds in cash, and advised the king to send commissioners to the United States and Europe with full power to negotiate new treaties, and to obtain a

on business, and became interested in the native people and their government. After a candid examination of the controversies existing between their own countrymen and the Hawaiian Government, they became convinced that the latter had been unjustly accused. Sir George offered to loan the government ten thousand pounds in cash, and advised the king to send commissioners to the United States and Europe with full power to negotiate new treaties, and to obtain a guarantee of the independence of the kingdom.

guarantee of the independence of the kingdom.

Accordingly Sir George Simpson, Haalilio, the king’s secretary, and Mr. Richards were appointed joint ministers-plenipotentiary to the three powers on the 8th of April, 1842.

Mr. Richards also received full power of attorney for the king. Sir George left for Alaska, whence he traveled through Siberia, arriving in England in November. Messrs. Richards and Haalilio sailed July 8th, 1842, in a chartered schooner for Mazatlan, on their way to the United States*

Mr. Richards also received full power of attorney for the king. Sir George left for Alaska, whence he traveled through Siberia, arriving in England in November. Messrs. Richards and Haalilio sailed July 8th, 1842, in a chartered schooner for Mazatlan, on their way to the United States*

*Their business was kept a profound secret at the time.

Proceedings of the British Consul—As soon as these facts became known, Mr. Charlton followed the embassy in order to defeat its object. He left suddenly on September 26th, 1842, for London via Mexico, sending back a threatening letter to the king, in which he informed him that he had appointed Mr. Alexander Simpson as acting-consul of Great Britain. As this individual, who was a relative of Sir George, was an avowed advocate of the annexation of the islands to Great Britain, and had insulted and threatened the governor of Oahu, the king declined to recognize him as British consul. Meanwhile Mr. Charlton laid his grievances before Lord George Paulet commanding the British frigate “Carysfort,” at Mazatlan, Mexico. Mr. Simpson also sent dispatches to the coast in November, representing that the property and persons of his countrymen were in danger, which introduced Rear-Admiral Thomas to order the “Carysfort” to Honolulu to inquire into the matter.

Recognition by the United States—Messres. Richards and Haalilio arrived in Washington early in December, and had several interviews with Daniel Webster, the Secretary of State, from whom they received an official letter December 19th, 1842, which recognized the independence of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and declared, “as the sense of the government of the United States, that the government of the Sandwich Islands ought to be respected; that no power ought to take possession of the islands, either as a conquest or for the purpose of the colonization; and that no power ought to seek for any undue control over the existing government, or any exclusive privileges or preferences in matters of commerce.” *

Secretary of State, from whom they received an official letter December 19th, 1842, which recognized the independence of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and declared, “as the sense of the government of the United States, that the government of the Sandwich Islands ought to be respected; that no power ought to take possession of the islands, either as a conquest or for the purpose of the colonization; and that no power ought to seek for any undue control over the existing government, or any exclusive privileges or preferences in matters of commerce.” *

*The same sentiments were expressed in President Tyler’s message to Congress of December 30th, and in the Report of the Committee on Foreign Relations, written by John Quincy Adams.

Success of the Embassy in Europe—The king’s envoys proceeded to London, where they had been preceded by the Sir George Simpson, and had an interview with the Earl of Aberdeen, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, on the 22d of February, 1843.

they had been preceded by the Sir George Simpson, and had an interview with the Earl of Aberdeen, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, on the 22d of February, 1843.

Lord Aberdeen at first declined to receive them as ministers from an independent state, or to negotiate a treaty, alleging that the king did not govern, but that he was “exclusively under the influence of Americans to the detriment of British interests,” and would not admit that the government of the United States had yet fully recognized the independence of the islands.

Sir George and Mr. Richards did not, however, lose heart, but went on to Brussels March 8th, by a previous arrangement made with Mr. Brinsmade. While there, they had an interview with Leopold I., king of the Belgians, who received them with great courtesy, and promised to use his influence to obtain the recognition of Hawaiian independence. This influence was great, both from his eminent personal qualities and from his close relationship to the royal families of England and France.

Encouraged by this pledge, the envoys proceeded to Paris, where, on the 17th, M. Guizot, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, received them in the kindest manner, and at once engaged, in behalf of France, to recognize the independence of the islands. He made the same statement to Lord Cowley, the British ambassador, on the 19th, and thus cleared the way for the embassy in England.

They immediately returned to London, where Sir George had a long interview with Lord Aberdeen on the 25th, in which he explained the actual state of affairs at the islands, and received an assurance that Mr. Charlton would be removed. On the 1st of April, 1843, the Earl of Aberdeen formally replied to the king’s commissioners, declaring that “Her Majesty’s Government are willing and have determined to recognize the independence of the Sandwich Islands under their present sovereign,” but insisting on the perfect equality of all foreigners in the islands before the law, and adding that grave complaints had been received from British subjects of undue rigor exercised toward them, and improper partiality toward others in the administration of justice. Sir George Simpson left for Canada April 3d, 1843.

Recognition of the Independence of the Islands—Lord Aberdeen, on the 13th of June, assured the Hawaiian envoys that “Her Majesty’s government had no intention to retain possession of the Sandwich Islands,” and a similar declaration was made to the governments of France and the United States.

At length, on the 28th of November, 1843, the two governments of France and England united in a joint declaration to the effect that “Her Majesty, the queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and His Majesty, the king of the French, taking into consideration the existence in the Sandwich Islands of a government capable of providing for the regularity of its relations with foreign nations have thought it right to engage reciprocally to consider the Sandwich Islands as an independent state, and never to take possession, either directly or under the title of a protectorate, or under any other form, of any part of the territory of which they are composed…”

This was the final act by which the Hawaiian Kingdom was admitted within the pale of civilized nations. Finding that nothing more could be accomplished for the present in Paris, Messrs. Richards and Haalilio returned to the United States in the spring of 1844. On the 6th of July they received a dispatch from Mr. J.C. Calhoun, the Secretary of State, informing them that the President regarded the statement of Mr. Webster and the appointment of a commissioner “as a full recognition on the part of the United States of the independence of the Hawaiian Government.”

This was the final act by which the Hawaiian Kingdom was admitted within the pale of civilized nations. Finding that nothing more could be accomplished for the present in Paris, Messrs. Richards and Haalilio returned to the United States in the spring of 1844. On the 6th of July they received a dispatch from Mr. J.C. Calhoun, the Secretary of State, informing them that the President regarded the statement of Mr. Webster and the appointment of a commissioner “as a full recognition on the part of the United States of the independence of the Hawaiian Government.”

U.S. Federal Court Acknowledges the Continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom and U.S. Violations of International Law

When the United States Senate resumed its debate of senate bill no. 222 to provide a government for the Territory of Hawai‘i in 1900, there was an exchange between Senator William Allen of Nebraska and Senator John Spooner of Wisconsin that warrants special attention. Two years earlier, Senator Allen voted against the annexation of the Hawaiian Islands by congressional legislation.

During the debate on July 4, 1898, Senator Allen said, “The Constitution and the statutes are territorial in their operation; that is, they can not have any binding force or operation beyond the territorial limits of the government in which they are promulgated. In other words, the Constitution and statutes can not reach across the territorial boundaries of the United States into the territorial domain of another government and affect that government or persons or property therein (31 Cong. Rec. 6635).”

During the debate on July 4, 1898, Senator Allen said, “The Constitution and the statutes are territorial in their operation; that is, they can not have any binding force or operation beyond the territorial limits of the government in which they are promulgated. In other words, the Constitution and statutes can not reach across the territorial boundaries of the United States into the territorial domain of another government and affect that government or persons or property therein (31 Cong. Rec. 6635).”

He continued to clarify, that the “power of acquiring additional territory, rests exclusively in the President and the Senate, that it is an executive power which in its very nature can not be exercised by the House of Representatives, and that the only method of exercising it is by treaty and not by joint resolution or act of Congress; and the case of Texas, when rightly understood, forms no exception to this rule; therefore an attempt to annex or acquire territory by act or joint resolution of Congress is in violation of the letter, spirit, and policy of the Constitution (id.).”

Consistent with his position in 1898, Senator Allen asserted on February 28, 1900, “I utterly  repudiate the power of Congress to annex the Hawaiian Islands by a joint resolution such as passed the Senate. It is ipso facto null and void (33 Cong. Rec. 2391).” If the annexation was null and void, then there would be no need to debate senate bill no. 222 that would establish an American government on Hawaiian territory. Senator Spooner response to Senator Allen was “that is a political question, not subject to review by the courts (id.).” He then reiterated, “The Hawaiian Islands were annexed to the United States by a joint resolution passed by Congress. I reassert…that that was a political question and it will never be reviewed by the Supreme Court or any other judicial tribunal (id.).”

repudiate the power of Congress to annex the Hawaiian Islands by a joint resolution such as passed the Senate. It is ipso facto null and void (33 Cong. Rec. 2391).” If the annexation was null and void, then there would be no need to debate senate bill no. 222 that would establish an American government on Hawaiian territory. Senator Spooner response to Senator Allen was “that is a political question, not subject to review by the courts (id.).” He then reiterated, “The Hawaiian Islands were annexed to the United States by a joint resolution passed by Congress. I reassert…that that was a political question and it will never be reviewed by the Supreme Court or any other judicial tribunal (id.).”

What did Senator Spooner mean that “it will never be reviewed by the Supreme Court or any other judicial tribunal.” He was referring to the “political question” doctrine. William Howard Taft acknowledged that Senator Spooner was “a great constitutional lawyer,” which is why he knew precisely what the political question doctrine was when he said it. Under this doctrine that was in use by American courts at the time, to include the United States Supreme Court, political questions were considered by the courts as factual determinations made by the executive and legislative branches. As such, these determinations, even if they were considered by the courts as unconstitutional, would bind the courts to accept them as conclusive. What Senator Spooner meant was no matter how illegal the annexation was, the American courts will have to accept it because Congress did it.

As an example, the U.S. Supreme Court in Williams v. Suffolk Ins. Co., 38 U.S. (13 Pet.) 415, 420 (1839) treated as binding on the court the executive’s determination that a given country was in control of foreign territory “whether the executive be right or wrong.” According to Nelson “an important branch of [the political question] doctrine operated to identify factual questions on which courts would accept the political branches’ determinations as binding.” See Caleb Nelson, Adjudication in the Political Branches, 107 Colum. L. Rev. 559, 592-93 (2007). Under this doctrine courts at the time did not question whether it had jurisdiction to resolve a political question “but rather enforced and applied the political branches’ determinations.” See Tara Leigh Grove, The Lost History of the Political Question Doctrine, 90 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1908, 1963 (Dec. 2015).

Senator Spooner’s statement is not only telling but malicious. The federal government knew that the illegal annexation of Hawai‘i would be locked within the American political system under the political question doctrine and never see the light of day. This shows an intent on the part of the United States government to conceal the fact that the annexation of Hawai‘i by a joint resolution, as Senator Allen stated, was “ipso facto null and void.” The political question doctrine, however, would later be revamped by the United States Supreme Court in Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962) that would ironically unlock the door in exposing the prolonged occupation of Hawai‘i and the violations of international law.

Moving away from the courts accepting the factual determinations of the political branches as binding, the Supreme Court would now assert a revised doctrine where the courts would deny it has jurisdiction to address a political question because that decision has to be addressed by either of the two political branches—the executive or legislative, not the judicial branch. The issue would no longer be the acceptance of the factual determinations made by the executive or legislative branches, but whether or not the courts have jurisdiction to hear the case. It would now become a question of whether a case was justiciable or non-justiciable. In other words, under the traditional doctrine where the courts did not dismiss as non-justiciable but rather enforced the political branches determinations whether they were “right or wrong,” the courts under the modern doctrine would dismiss as non-justiciable because there exists a political question.

Today the invoking of the political question doctrine in cases that have been filed in federal courts come by way of a motion to dismiss under Rule 12(b)(1) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure or done by the court’s own volition called sua sponte. Rule 12(b)(1) addresses subject matter jurisdiction, which is whether the court has jurisdiction to hear the case before it. Where a motion to dismiss on subject matter jurisdiction grounds would be filed is in a situation where a prosecutor is attempting to prosecute someone for murder in traffic court. A traffic court does not have subject matter jurisdiction to prosecute a murder case, another type of court does. Applying the modern political question doctrine, the American courts would say the proper jurisdiction is either with executive or legislative branches of government and not the courts.

Therefore, the court’s dismissal of the case because of a political question only addresses the jurisdictional question of whether the court can preside over the case and not the merits of the case. In fact, under the modern doctrine, when a court dismisses a case as a political question under Rule 12(b)(1), the court accepts as true the factual allegations in the complaint.

In 2008, the federal district court in Washington, D.C., dismissed a case concerning Taiwan as a political question under Rule 12(b)(1) in Lin v. United States, 539 F. Supp. 2d 173 (D.D.S. 2008). The federal court in its order stated that it “must accept as true all factual allegations contained in the complaint when reviewing a motion to dismiss pursuant to Rule 12(b)(1).” When this case went on appeal, the D.C. Appellate Court underlined the modern doctrine of the political question, “We do not disagree with Appellants’ assertion that we could resolve this case through treaty analysis and statutory construction; we merely decline to do so as this case presents a political question which strips us of jurisdiction to undertake that otherwise familiar task.” See Lin v. United States, 561 F.3d 506 (2009).

In 2018, federal judge Tanya S. Chutkan presided over Sai v. Trump—Petition for Writ of Mandamus, which sought an order from the federal court to compel President Trump to comply with the 1907 Hague Convention, IV, and the 1949 Geneva Convention, IV, by administering the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an occupied State. The case was filed on June 25, 2018 with the United States District Court for the District of Columbia and assigned civil case no. 1:18-cv-01500.

The factual allegations of the complaint were stated in paragraphs 79 through 205 under the headings From a State of Peace to a State of War, The Duty of Neutrality by Third States, Obligation of the United States to Administer Hawaiian Kingdom laws, Denationalization through Americanization, The State of Hawai‘i is a Private Armed Force, The Restoration of the Hawaiian Kingdom Government, Recognition De Facto of the Restored Hawaiian Government, War Crimes: 1907 Hague Convention, IV, and War Crimes: 1949 Geneva Convention, IV.

On September 11, 2018, Judge Chutkan, on her own accord (sua sponte), issued an order dismissing the case as a political question. On the very same day the U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia filed a “Motion for Extension of Time to Answer in light of the order dismissing this action,” but it was denied by minute order. Judge Chutkan stated, “Because Sai’s claims involve a political question, this court is without jurisdiction to review his claims and the court will therefore DISMISS the Petition.” By dismissing the complaint, the Court accepted “as true all factual allegations contained in the complaint.”

Under the traditional political question doctrine, the Federal Court would have accepted as true the annexation of Hawai‘i even though it wasn’t, but under the modern doctrine it accepted as true the “illegality” of the annexation as well as the violations of international law since the American invasion of the Hawaiian Kingdom on January 16, 1893.

For the first time since President Grover Cleveland, in his message to the Congress on December 18, 1893, presented the facts of the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government, the United States government, through its federal court in Washington, D.C., accepted “as true” the facts of the prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the commission of war crimes.

The proper venue for resolving the violations of international law is not with the executive or legislative branches of the United States government, but rather international bodies, which will include the International Commission of Inquiry in Incidents of War Crimes in the Hawaiian Islands—The Larsen Case (Hawaiian Kingdom – Lance Paul Larsen) under the jurisdiction of the Permanent Court of Arbitration. These proceedings stemmed from the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom arbitration.

The United States has admitted to the violations of international law. Drawing from the Miranda warning, “Anything you say may be used against you in a court of law.”

Big Island Video News (BIVN): Ruggles Puts Hawaii Officials On Notice For Pillaging (Nov. 20, 2018)

#ProtectedPersonsHawaii

#WarCrimesHawaii

Council Member Ruggles Places the State of Hawai‘i on Notice for Pillaging Protected Persons

Council member Jen Ruggles released a letter today that she had sent to Governor Ige, every mayor, and every county taxation department in the State of Hawai‘i regarding “War crimes of pillaging committed against Protected Persons by the State of Hawai‘i and its Four Counties.”

Council member Jen Ruggles released a letter today that she had sent to Governor Ige, every mayor, and every county taxation department in the State of Hawai‘i regarding “War crimes of pillaging committed against Protected Persons by the State of Hawai‘i and its Four Counties.”

The letter begins by stating, “To my dismay, I have become aware of Hawai‘i’s status as a nation-state, under international law, which has been under an illegal occupation by the United States since it, by its own admission, illegally overthrew the Hawaiian Kingdom government on January 17, 1893.” Referring to President Cleveland’s 1893 address to the U.S. Congress where he declared U.S. had committed “an act of war” against the Hawaiian Kingdom, she writes, “these acts of war created a state of war between itself and the Hawaiian Kingdom…International law bound, and still binds, the United States to adhere to the law of occupation.”

Ruggles also referred to the United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, Dr. Alfred de Zayas’ memorandum sent to Hawaii State judges this past February which stated Hawai‘i was “under a strange form of occupation by the United States resulting from an illegal military occupation and a fraudulent annexation.”

“After reading Dr. de Zayas’s memorandum,” Ruggles wrote, “I attempted to verify his claim of ‘a fraudulent annexation.’ It became apparent to me that there is no clear U.S. constitutional basis for the enforcement of United States law on Hawaiian Kingdom territory…As a Council member, I have come to understand that legislation is limited to the territorial jurisdiction of the law-making body. The U.S. Congress has no constitutional authority, nor any authority under international law, to unilaterally annex a foreign country by a joint resolution.”

Ruggles also noted that according to international law definitions, what is called the “State of Hawai‘i” is, in fact, an “organized armed force.” “The State of Hawai‘i cannot, therefore claim to be a lawful government because its only claim to authority derives from U.S. congressional legislation that has no extraterritorial effect,” Ruggles wrote, “The ‘State of Hawai‘i’ meets the jus in bello—the laws of war definition of an organized armed group acting for and on behalf of the United States within the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom.”

According to Ruggles, because there is no evidence that Hawaii was ever legally made apart of the United States, the laws of occupation apply. These laws would include the Hague and Geneva Conventions, which are U.S. ratified treaties. According to Title 18, section 2441 of the United States Code, any breach to these treaties constitute “war crimes.”

Article 64 of the 1949 Geneva Convention mandates that the laws of the occupied territory must remain in force. Ruggles says these laws include the 1882 Hawaiian Kingdom Act To Consolidate and Amend the Law Relating to Internal Taxes which consists of poll, school, dog, horse, mule, road, and real and personal property taxes. Ruggles asserts that the State of Hawaii and the four counties collection of money from protected persons is a form of pillaging.

Black’s Law dictionary defines plunder as to “pillage or loot. To take property from persons or places by open force, and this may be in course of war…The term is also used to express the idea of taking property from a person or place, without just right.” The U.S. ratified Hague and Geneva Conventions specifically prohibit pillaging.

“This letter serves to give you both knowledge, and ‘awareness of the factual circumstances that established the existence of an armed conflict’ between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States, the application of the HCIV and GCIV, and the protection afforded aboriginal Hawaiians as protected persons,” Ruggles wrote, “Therefore, you must cease and desist from committing these war crimes unless the State of Hawai‘i transforms itself into a Military Government recognizable under international law”

Council member Ruggles concluded the letter with an excerpt from a report Dr. Keanu Sai had provided Governor Ige’s Chief of Staff, Mike McCartney in 2015 titled “Report on Military Government.” According to the report, the State of Hawaii is obligated to comply with U.S. Army Field Manual FM 27-5 and establish a military government to work with the acting Hawaiian Kingdom Government to provisionally serve as the administrator of the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

During Ruggles’ October Town Hall she explained how she is doing her job “as mandated by her oath to uphold the U.S. Constitution that says treaties are the supreme law of the land through putting every agent of the United States in Hawaii concerning the rights of protected persons on notice for violations of the Hague and Geneva Conventions.”

Ruggles confirmed Governor Ige, Mayor Kim, Mayor Arakawa, Mayor Caldwell, Mayor Carvalho, Linda Chu Takayama, Lisa Miura, Mark Walker, Nelson H. Koyanagi, Jr., and Ken Shimonishi all received her letter on November 19th, 2018.

#ProtectedPersonsHawaii

#WarCrimesHawaii

Kamehameha Schools Midkiff Learning Center: Hawai‘i Sovereignty Symposium

NEA Teachers Union Published Third and Final Article on the American Occupation of Hawai‘i

As part of a three part series the National Education Association (NEA) has published the third and final article on the American occupation of Hawai‘i. The NEA is the largest labor union in the United States comprised of public school teachers, administrators, and faculty and administrators of universities. This third and final article is titled “The Impact of the U.S. Occupation on the Hawaiian People.”

The NEA’s article stems from a resolution that was passed by its delegates who met at their annual convention in 2017 in Boston, Massachusetts.

The resolution was introduced by the delegates of the Hawai‘i State Teachers Association, which is an affiliate labor union of the NEA, and it passed on July 4, 2017. The resolution was referred to as New Business Item 37, which stated:

“The NEA will publish an article that documents the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Monarchy in 1893, the prolonged occupation of the United States in the Hawaiian Kingdom and the harmful effects that this occupation has had on the Hawaiian people and resources of the land.”

#ProtectedPersonsHawaii

#WarCrimesHawaii

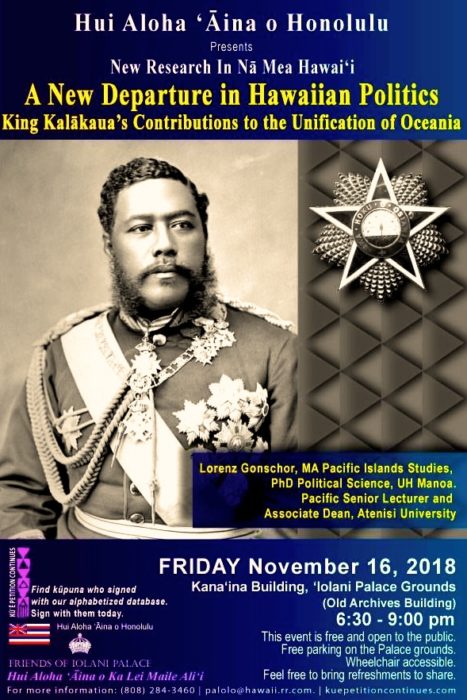

King Kalakaua’s Contribution to the Unification of Oceania

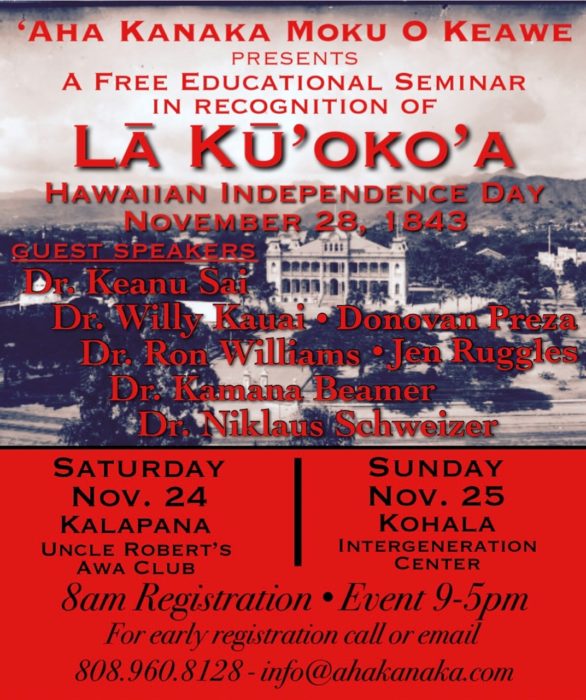

La Ku‘oko‘a (Independence Day) on Hawai‘i Island

Unfit for a Queen: Eugenics and Hawaiian Education in Territorial Hawai‘i