The Preliminary Report on the Legal Status of Land Titles throughout the Realm of July 16, 2020, by the Royal Commission of Inquiry, is a comprehensive report as to why the majority of land titles today throughout Hawai‘i are defective. This includes properties claimed to be owned by billionaires such as Mark Zuckerberg’s claim to property on the island of Kaua‘i, and Larry Ellison’s claim to 98% of the island of Lana‘i. The Royal Commission of Inquiry also published a Supplemental Report on Title Insurance on October 20, 2020.

All titles to real estate throughout the Hawaiian Kingdom are subject to Hawaiian laws despite the unlawful overthrow of its government by the United States in 1893. As such, all titles that have since been alleged to have been conveyed after January 17, 1893, are void ab initio due to forged certificates of acknowledgment by individuals impersonating public officers. This includes all purported conveyances of Government or Crown lands after January 17, 1893, and any judicial proceedings regarding titles to land.

Hawaiian law, however, would have recognized these acts of the insurgents as being valid if Queen Lili‘uokalani was restored to office. The agreed upon conditions of restoration between the United States and the Hawaiian Kingdom provided, “a general amnesty to those concerned in setting up the provisional government and a recognition of all its bona fide acts and obligations.” Regarding the “bona fide acts and obligations,” the Queen stated in her letter dated December 18, 1893, to the U.S. Minister Albert Willis, who was negotiating on behalf of President Cleveland, “I further solemnly pledge myself and my Government, if restored, to assume all the obligations created by the Provisional Government, in the proper course of administration, including all expenditures for military or police services, it being my purpose, if restored, to assume the Government precisely as it existed on the day when it was unlawfully overthrown.”

By this agreement, the United States acknowledged the acts done by the insurgency were not “bona fide” until after the Queen was restored. The Queen was not restored and, therefore, the insurgency continued to unlawfully impersonate public officers of the Hawaiian Kingdom in the chain of title. These defects in title are covered risks in the owner’s and lender’s title insurance policies as:

- forgery, fraud, undue influence, duress, incompetency, incapacity, or impersonation;

- failure of any person or Entity to have authorized a transfer or conveyance;

- a document affecting Title not properly created, executed, witnessed, sealed, acknowledged, notarized, or delivered;

- a document executed under a falsified, expired, or otherwise invalid power of attorney;

- a document not properly filed, recorded, or indexed in the Public Records including failure to perform those acts by electronic means authorized by law;

- a defective judicial or administrative proceeding.

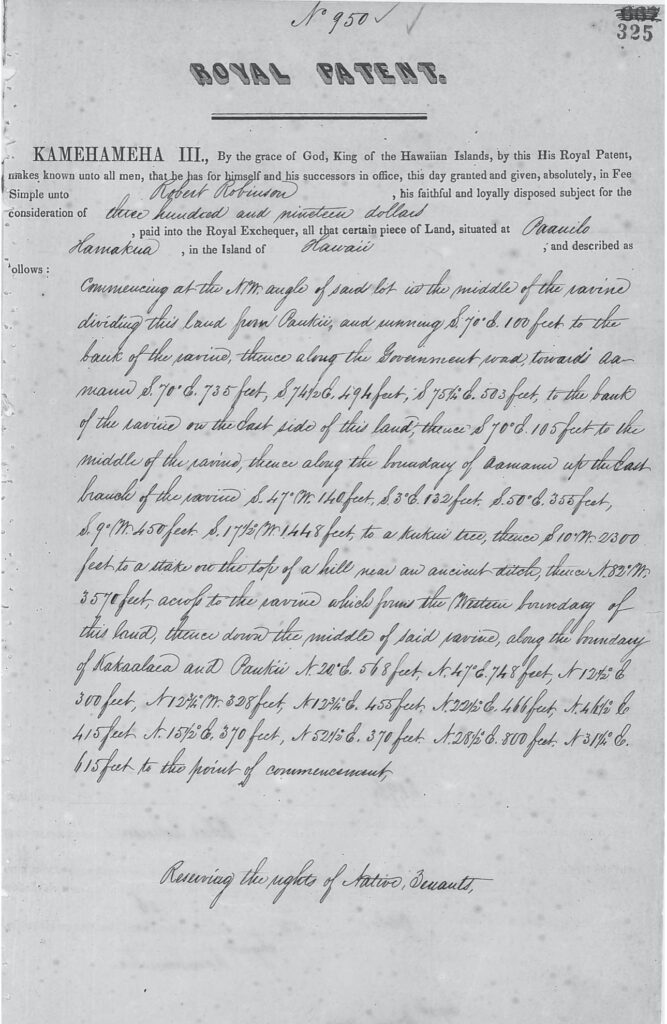

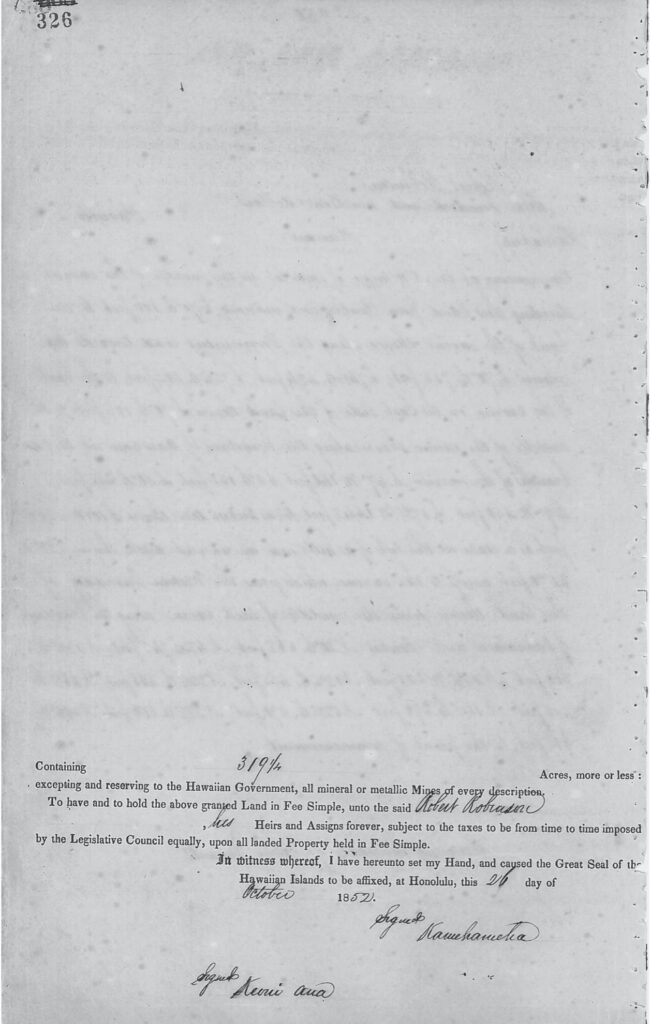

Here’s an example of a “bona fide” Royal Patent issued on October 26, 1852.

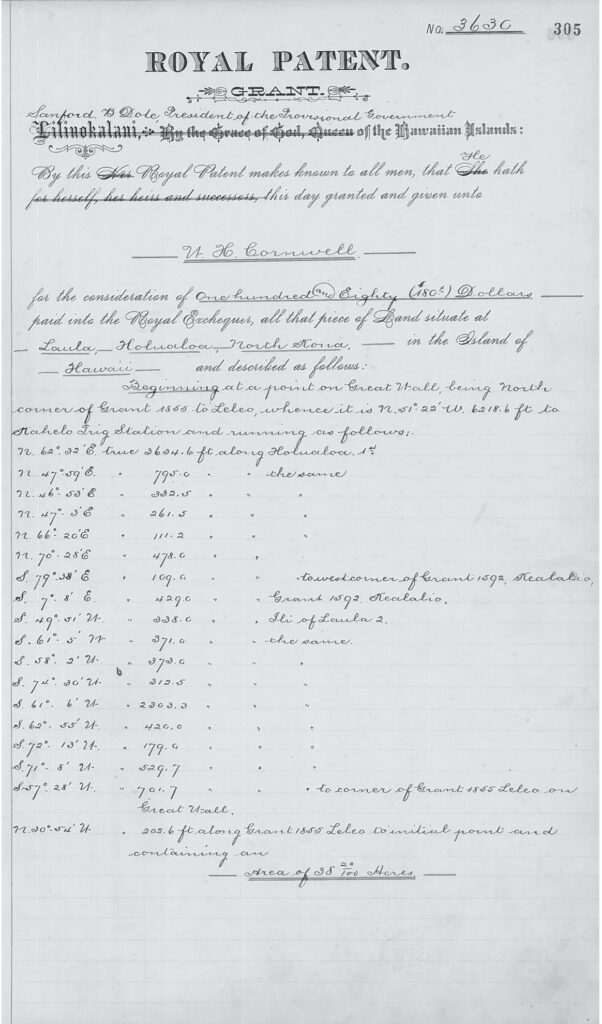

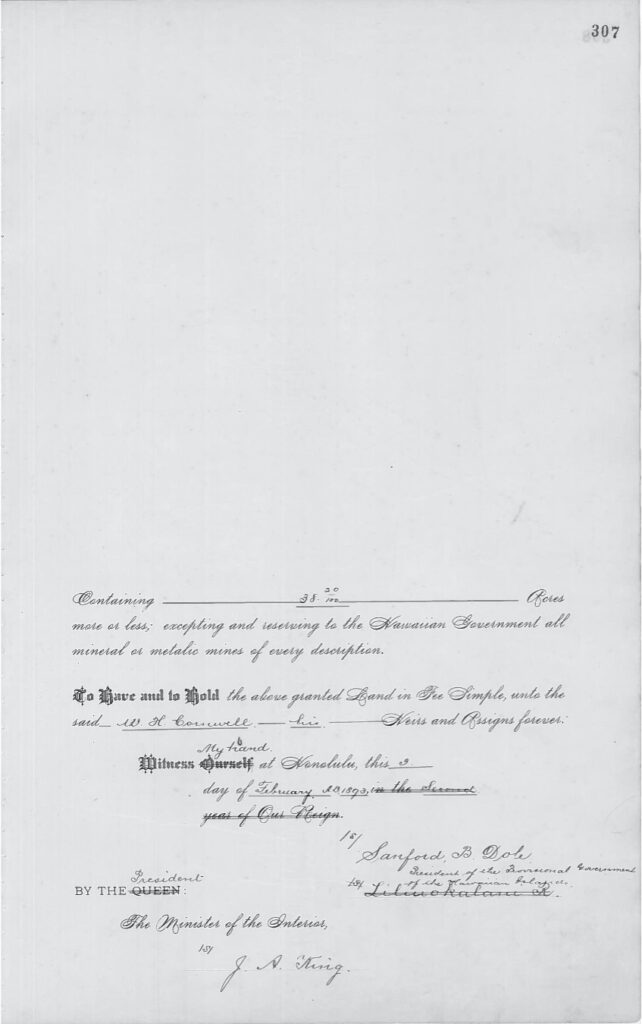

Here is an example of a “forged” Royal Patent issued just one month after the overthrow of the Hawaiian government by the United States dated February 3, 1893. This is an example of what President Cleveland sought to remedy as a “bona fide” act by the insurgents in his agreement of restoration with Queen Lili‘uokalani.

Any property today that derives from this forged Royal Patent is void, but the loss could be covered by an owner’s policy of title insurance. Hill, Steindorff and Widener, in their “Recent Developments in Title Insurance Law,” reported that in 2012, a California Federal District Court, in Gumapac v. Deutsche Bank National Trust, found that “a title report revealed a defect of title by virtue of an executive agreement between President Grover Cleveland and Queen Lili‘uokalani of the Hawaiian Kingdom that rendered any notary actions unlawful. Thus, the deed of conveyance to the homeowners was nullified.” In Hawai‘i, claimants under both an owner’s or lender’s title insurance policy have a duty to immediately notify their insurer of any title defects that affect title to the property or the mortgage that secures the repayment of a loan.

During this time of high prices at the gas pump added on to the high cost of living in the Hawaiian Islands, watching how you spend your money is critical to surviving during this inflation crisis brought upon the residents of Hawai‘i by the United States prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom since 1893. But there is some monetary light that many people in Hawai‘i can take advantage of, which is filing a claim with their title insurance company under an owner’s policy, and notifying your bank or lender to file a claim so that your debt owed to the lender is paid off.

When individuals want to borrow money from a bank or lender, they are told by the lender to first go to an escrow company to purchase a lender’s title insurance policy in the amount to be borrowed. Prior to the issuing of a title insurance policy, the escrow company does a title search on the property that the borrower intends to use as a security instrument, also called a mortgage, to ensure the repayment of the loan. A title insurance company that works with the escrow company will then insure the accuracy of the title search. Only when the borrower purchases the title insurance policy to protect the lender from any title defect that affects the mortgaged debt is when escrow comes to a close.

There is another type of title insurance policy that is issued by the escrow company and that is an owner’s policy that protects the owner and not the lender. An owner’s policy is normally purchased when an individual borrows money for the first time and has to go to an escrow company. Many people don’t even know that they may have purchased an owner’s policy unless they look at their closing papers from escrow. Unlike a lender’s policy that covers the debt owed to the lender, an owner’s policy covers the owner’s loss, which is the appraised value of the property at the time the policy is taken out.

Most people are unaware as to what title insurance is and how it works. Typical insurance policies, such as car insurance or flood insurance, insure against a future cause of damage, that may or may not occur. Title insurance, on the other hand, insures against a past cause of damage called defects in the chain of title that affect ownership of real property. According to Burke’s Law of Title Insurance, title insurance is an agreement to indemnify the insured for losses incurred “by either on-record and off-record defects that are found in the title or interest in an insured property to have existed on the date on which the policy is issued.” And Black’s Law Dictionary defines title insurance as a “policy issued by a title company after searching the title…and insuring the accuracy of its search against claims of title defects.” As the Florida Court of Appeals, in McDaniel v. Lawyers Title Guar. Fund, stated, “One of the reasonable expectations of a policyholder who purchases title insurance is to be protected against defects in his title which appear of record.”

Title insurance is a one-time paid premium agreement under both an owner’s policy, that protects the interests of the owner of the property, and a lender’s policy, that protects the lender’s interest—the debt owed—in the mortgaged lien on the property. The owner’s policy does not exceed the amount of coverage on the policy. The lender’s policy coverage reduces as the debt is being paid by the borrower, which will eventually expire once the final payment of the loan is made. Burke explains that coverage under an owner’s policy, however, “lasts for as long as the insured has some liability for title defect, whether as the present owner or possessor, or as a vendor [grantor] and warrantor of the state of the title upon some later sale. There is no such thing as term title insurance. Its policy might, potentially, last forever.” A grantor’s covenant is explicitly stated in its warranty deed where it states, “and that the Grantor will WARRANT AND DEFEND the same unto the Grantee against the lawful claims and demands of all persons.”

Being that title insurance is an indemnity agreement, Burke states that the insurer can also act as a surety, which “is a person agreeing to be answerable for the actions of another.” According to Burke, when there is a breach of covenant and warranty of title by a grantor, the “title insurer might agree to remedy a breach of the covenant for further assurances by bringing the litigation required to cure a title, instead of letting the [grantor] do it.” The right to remedy, as a surety, is provided under Condition no. 5 of both the owner and lender policies that states the insurer “shall have the right, in addition to the options contained in Section 7 of these Conditions, at its own cost, to institute and prosecute any action or proceeding or to any other act that in its opinion may be necessary or desirable to establish the Title, as insured, or to prevent or reduce loss or damage to the Insured.” According to Hill, Steindorff and Widener, an Illinois Appellate Court concluded “that although the title company did not have an ownership interest in the property, the company had issued a title insurance policy and could have redeemed the taxes on the subject property on behalf of the prior owner, to whom it had issued a title policy.”

When the title insurance company is given the evidence of proof of loss of title in a claim letter by the insured, the company has thirty-days to either initiate proceedings to remedy the defect of the title or make a payment to the insured covered in the insurance policy. According to the federal court in Davis v. Stewart Title Guaranty Co., “In law, a title is either good or bad.” The Missouri Supreme Court, in Kent & Obear v. Allen, stated, “the validity of the title arising, the question must be determined whether it is good or bad. We cannot object to the title of the respondent that it is doubtful or unmarketable.” The Davis court also concluded that the “liability of the insurer was definitely fixed under the terms of the policy,” to either remedy the defect or the “payment of loss was due, under the policy, ‘within 30 days thereafter.’”

To determine “on-record defects in title,” a title insurer relies on a competent title search. According to Baker, Miceli, Sirmans, and Turnbull’s article, “Optimal Title Search,” in the Journal of Legal Studies, “Some states have no set length but instead require that the entire title history of a parcel of land be searched back to the state’s date of patent,” which include Alaska, Arizona, California, Florida, Idaho, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, North and South Dakota, Oregon, Texas and Washington. At the highest number of years for a title search are Colorado, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, North and South Dakota, and Wyoming at 187 years. At the low end of a 30-year search are New Mexico, Oklahoma and Tennessee. In a study of optimal title searches, Hawai‘i, Illinois and Indiana were excluded from the analysis because they provided “indeterminate search lengths.”

In one particular preliminary report by Title Guaranty of Hawai‘i, its title search only went back one conveyance. This lack of a full title search by Title Guaranty, who serves as an agent for title insurance companies, back to the original patent, called Royal Patents, only amplifies the purpose of title insurance as an indemnity agreement. It is not a guaranty of the state of the title. According to the Pennsylvania court, in Hicks v. Saboe, “The purpose of title insurance is to protect the insured…from loss arising from defects in the title which he acquires.” The federal court, in Omega Healthcare Investors, Inc. v. First Am. Title Ins. Co., stated, “Because title insurance [is] a contract of indemnity, the insurer does not guarantee the state of the title, but agrees to pay for any loss resulting from a defective title.” The Maryland Appeals Court, in Stewart Title Guar. Co. v. West, explained that a title insurer does not have a duty to advise “on the state of title to the property, but to insure against…loss resulting from any defects.” Therefore, “the title insurer does not ‘guarantee’ the status of the grantor’s title. As an indemnity agreement, the insurer agrees to reimburse the insured for loss or damage sustained as a result of title problems, as long as the coverage for the damages incurred is not excluded from the policy.”

Since 1994, the State of Hawai‘i courts have applied, whenever the issue of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s continued existence as a State arose in court proceedings, the State of Hawai‘i v. Lorenzo case at the Intermediate Court of Appeals (ICA), which has come to be known as the Lorenzo doctrine in the federal courts. For 28 years, both the State of Hawai‘i courts and the federal courts have been applying the Lorenzo doctrine wrong. Under international law, which the ICA acknowledged may affect its rationale of placing the burden on the defendant to prove the Hawaiian Kingdom “exists as a State,” shifts the burden on the party opposing the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom that it “does not exist as a State.” In international arbitration proceedings at the Permanent Court of Arbitration from 1999-2001, in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, PCA case no. 1999-01, the PCA acknowledged the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist as a State and the Council of Regency as its government. Because the Hawaiian Kingdom still exists, so do the laws that apply to real property.

In a denial letter to a title insurance claimant, Michael J. Moss, Senior Claims Counsel for Chicago Title Insurance Company, specifically referenced the Lorenzo doctrine applied in two State of Hawai‘i court cases and one federal court case as a basis to decline the insurance claim under an owner’s title insurance policy in the amount of $178,000.00. Moss stated:

The Hawaiian Courts have consistently found that the Kingdom of Hawai‘i is no longer recognized as a sovereign state by either the federal government or by the State of Hawai‘i. See State v. Lorenzo, 77 Hawai‘i 219, 221, 883 P.2d 641, 643 (Haw.App.1994); accord State v. French, 77 Hawai‘i 222, 228, 883 P.2d 644, 649 (Haw.App.1994); Baker v. Stehua, CIV 09-00615 ACK-BMK, 2010 WL 3528987 (D. Haw. Sept. 8, 2010).

Like the courts of the State of Hawai‘i and the federal courts, the Senior Claims Counsel incorrectly applied the Lorenzo doctrine, which should have been in favor of the title insurance claimant. The title insurance claim was that the “Owner’s deed was not lawfully executed according to Hawaiian Kingdom law [because] the notaries public and the Bureau of Conveyance weren’t part of the Hawaii[an] Kingdom, that the documents in [the claimant’s] chain of title were not lawfully executed.” In other words, the Lorenzo doctrine, when applying international law correctly, would compel the title insurance company to pay the claimant his $178,000.00 covered under the owner’s title insurance policy he had purchased to protect him in case there was a defect in the title.

To find out if you have an owner’s policy check your closing papers from escrow to see if you purchased a policy. Or you can call your escrow company or companies that you went to in the past. If you have a mortgage you did purchase a title insurance policy to protect the lender. To file a claim under your owner’s policy download this MSWord document and fill in the necessary information after you have your owner’s policy in hand. To send a letter to your lender to file an insurance claim under the lender’s policy you purchased download this MSWord document and fill in the necessary information.

Submitting an insurance claim is a private matter that is subject to the terms of your contract or policy. Under the terms of the policy you and the lender are obligated to notify the insurance company if you have been made aware that there are defects in your title. It is suggested that you carefully read over your title insurance policy before you send your claim to the insurance company by certified mail. The lender, not the borrower, has a copy of the lender’s policy that was purchased by the borrower. Once the claim, whether by the owner or the lender, is received by the insurance company you will receive a letter acknowledging your claim and assigning it a claim number. This letter by the insurance company will begin the thirty-day window to either remedy the defect in the title or pay the amount covered under the policy.