In a blistering report by the Chinese Foreign Ministry on American imperialism, China acknowledges the United States unlawful annexation of Hawai‘i in 1898. The Foreign Ministry reported:

Since it gained independence in 1776, the United States has constantly sought expansion by force: it slaughtered Indians, invaded Canada, waged a war against Mexico, instigated the American-Spanish War, and annexed Hawai‘i.

After World War II, the wars either provoked or launched by the United State included the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Gulf War, the Kosovo War, the War in Afghanistan, the Iraq War, the Libyan War and the Syrian War, abusing its military hegemony to page the way for expansionist objectives.

In recent years, the U.S. average annual military budget has exceeded 700 billion U.S. dollars, accounting for 40 percent of the world’s total, more than the 15 countries behind it combined.

The United States has about 800 overseas military bases, with 173,000 troops deployed in 159 countries.

The Foreign Ministry also cited a Tufts University report that found the United States carried out almost 400 military interventions from 1776 to 2019.

When the attempt to acquire the Hawaiian Islands by a treaty of cession failed in 1898 because of protests by Queen Lili‘uokalani, Head of State of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and Hawaiian subjects and supporters, the breakout of the Spanish-American War prompted the United States to unilaterally annex Hawai‘i by enacting a congressional statute called a joint resolution of annexation. On May 31, 1898, the U.S. Senate went into secret session on the subject of unilaterally annexing the Hawaiian Islands as a military necessity. The senators knew that a joint resolution, as American municipal law, has no effect beyond the borders of the United States, but the President could exercise his war powers by signing the joint resolution into law. Senator Henry Cabot Lodge stated:

If I had been permitted to continue I could have been permitted to continue I could have finished in ten minutes. I have really made the argument which I desire to make. If it had not been that it would have precipitated a protracted debate, I should have argued then what has been argued ably since we came into secret legislative session, that at this moment the Administration was compelled to violate the neutrality of those [Hawaiian] islands, that protests from foreign representatives had already been received, and complications with other powers were threatened, that the annexation or some action in regard to those islands had become a military necessity.

The word “necessity” was used 21 times in the secret session, but no one would know what was discussed because secrecy prevented the public from seeing it until 1969.

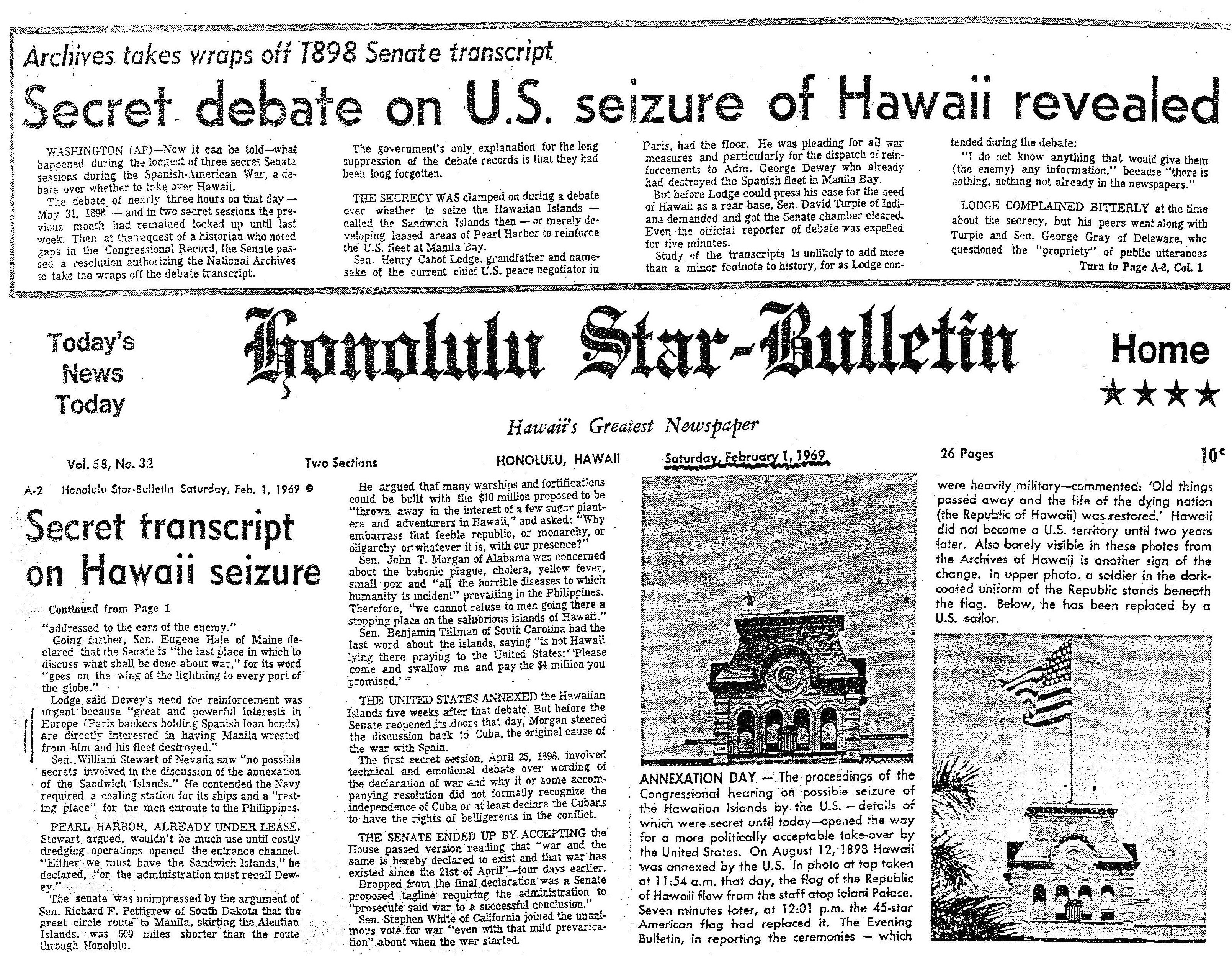

Honolulu Star-Bulletin, Saturday, February 1, 1969 reported:

WASHINGTON (AP) – Now it can be told—what happened during the longest of three Senate sessions during the Spanish-American War, a debate over whether to take over Hawaii.

The debate of nearly three hours on that day—May 31, 1898—and in two secret sessions the previous month had remained locked up until last week. Then at the request of a historian who noted gaps in the Congressional Record, the Senate passed a resolution authorizing the National Archives to take the wraps off the debate transcript.

The government’s only explanation for the long suppression of the debate records is that they had been long forgotten.

THE SECRECY WAS clamped on during a debate over whether to seize the Hawaiian Islands—called the Sandwich Islands then—or merely developing leased areas of Pearl Harbor to reinforce the U.S. fleet at Manila Bay.

Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge, grandfather and namesake of the current chief U.S. peace negotiator in Paris, had the floor. He was pleading for all war measures and particularly for the dispatch of reinforcements to Adm. George Dewey who already had destroyed the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay.

But before Lodge could press his case for the need of Hawaii as a rear base, Sen. David Turpie of Indiana demanded and got the Senate chamber cleared. Even the official reporter of debate was expelled for five minutes.

Study of the transcripts is unlikely to add more than a minor footnote to history, for as Lodge contended during the debate:

“I do not know anything that would give them (the enemy) any information,” because “there is nothing, nothing not already in the newspapers.”

LODGE COMPLAINED BITTERLY at the time about the secrecy, but his peers went along with Turpie and Sen. Georg Gray of Delaware, who questioned the “propriety” of public utterances “addressed to the ears of the enemy.”

Going further, Sen. Eugene Hale of Maine declared that the Senate is “the last place in which to discuss what shall be done about war,” for its word “goes on the wing of the lightning to every part of the globe.”

Lodge said Dewey’s need for reinforcement was urgent because “great and powerful interests in Europe (Paris bankers holding Spanish loan bonds) are directly interested in having Manila wrested from him and his fleet destroyed.”

Sen. William Stewart of Nevada saw “no possible secrets involved in the discussion of the annexation of the Sandwich Islands.” He contended the Navy required a coaling station for its ships and a “residing place” for the men enroute to the Philippines.

PEARL HARBOR, ALREADY UNDER LEASE, Stewart argued, wouldn’t be much use until costly dredging operations opened the entrance channel. “Either we must have the Sandwich Islands,” he declared, “or the administration must recall Dewey.”

The senate was unimpressed by the argument of Sen. Richard F. Pettigrew of South Dakota that the great circle route to Manila, skirting the Aleutian Islands, was 500 miles shorter than the route through Honolulu.

He argued that many warships and fortifications could be built with $10 million proposed to be “thrown away in the interest of a few sugar planters and adventures in Hawaii,” and asked: “Why embarrass that feeble republic, or monarchy, or oligarchy or whatever it is, with our presence?”

Sen. John T. Morgan of Alabama was concerned about the bubonic plague, cholera, yellow fever, small pox and “all the horrible diseases to which humanity is incident” prevailing in the Philippines. Therefore, “we cannot refuse to men going there a stopping place on the salubrious islands of Hawaii.”

Sen. Benjamin Tillman of South Carolina had the last word about the islands, saying “is not Hawaii lying there praying to the United States: ‘Please come and swallow me and pay the $4 million you promised.’”

THE UNITED STATES ANNEXED the Hawaiian Islands five weeks after the debate. But before the Senate reopened its doors that day, Morgan steered the discussion back to Cuba, the original cause of the war with Spain.

The first secret session, April 25, 1898, involved technical and emotional debate over wording of the declaration of war and why it or some accompanying resolution did not formally recognize the independence of Cuba or at least declare the Cubans to have the rights of belligerents in the conflict.

THE SENATE ENDED UP BY ACCEPTING the House passed version reading that “war and the same is hereby declared to exist and that war has existed since the 21st of April”—four days earlier.

Dropped from the final declaration was a Senate proposed tagline requiring the administration to “prosecute said war to a successful conclusion.”

Sen. Stephen White of California joined the unanimous vote for war “even with that mild prevarication” about when the war started.