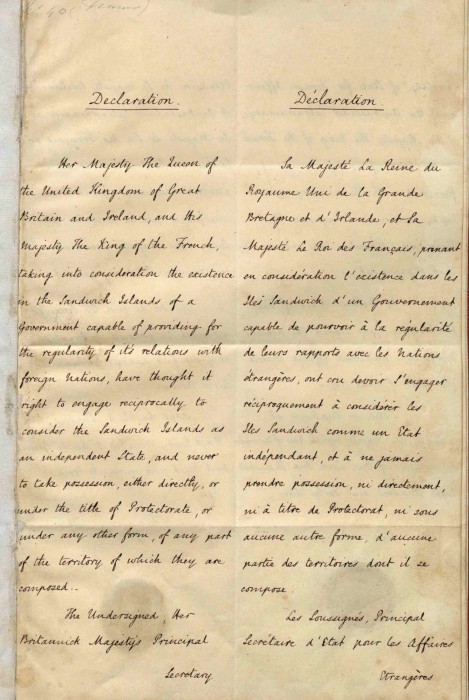

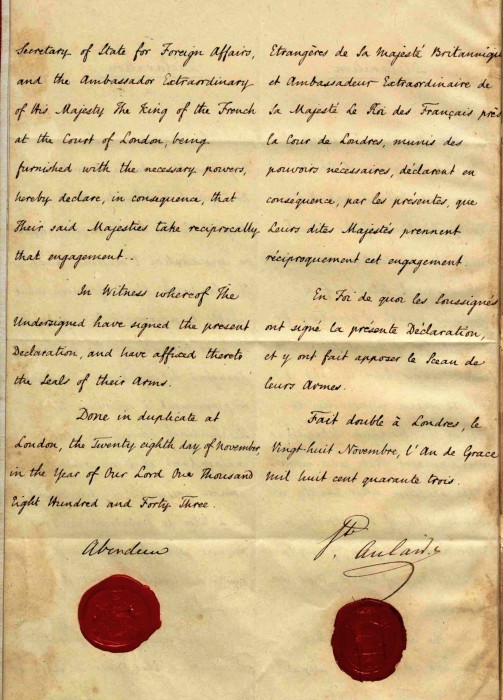

The Hawaiian Kingdom received the recognition of its independence and sovereignty by joint proclamation from the United Kingdom and France on November 28, 1843, and by the United States of America on July 6, 1844.

At the time of the recognition of Hawaiian independence, the Hawaiian Kingdom’s government was a constitutional monarchy that developed a complete system of laws, both civil and criminal, and have treaty relations of a most favored nation status with the major powers of the world, including the United States of America.

At the time of the recognition of Hawaiian independence, the Hawaiian Kingdom’s government was a constitutional monarchy that developed a complete system of laws, both civil and criminal, and have treaty relations of a most favored nation status with the major powers of the world, including the United States of America.

A. Permanent Population

According to Professor Crawford, The Creation of States in International Law, 2nd ed. (2006), p. 52, “If States are territorial entities, they are also aggregates of individuals. A permanent population is thus necessary for statehood, though, as in the case of territory, no minimum limit is apparently prescribed.” Professor Giorgetti, A Principled Approach to State Failure (2010), p. 55, explains “Once recognized, States continue to exist and be part of the international community even if their population changes. As such, changes in one of the fundamental requirements of statehood do not alter the identity of the State once recognized.”

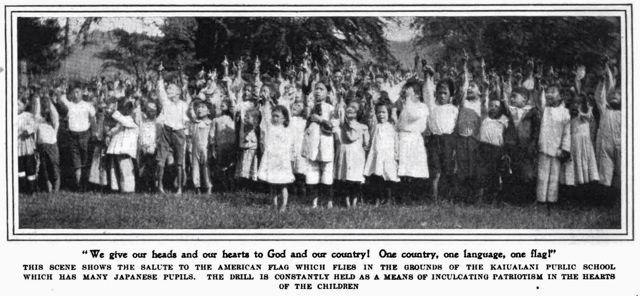

In his report to U.S. Secretary of State Walter Gresham, Special Commissioner James Blount reported on June 1, 1893, “The population of the Hawaiian Islands can but be studied by one unfamiliar with the native tongue from its several census reports. A census is taken every six years. The last report is for the year 1890. From this it appears that the whole population numbers 89,990. This number includes natives, or, to use another designation, Kanakas, half-castes (persons containing an admixture of other than native blood in any proportion with it), Hawaiian-born foreigners of all races or nationalities other than natives, Americans, British, Germans, French, Portuguese, Norwegians, Chinese, Polynesians, and other nationalities. Americans numbered 1,928; natives and half-castes, 40,612; Chinese, 15,301; Japanese, 12,360; Portuguese, 8,602; British, 1,344; Germans, 1,034; French, 70; Norwegians, 227; Polynesians, 588; and other foreigners 419. It is well at this point to say that of the 7,495 Hawaiian-born foreigners 4,117 are Portuguese, 1,701 Chinese and Japanese, 1,617 other white foreigners, and 60 of other nationalities.”

In his report to U.S. Secretary of State Walter Gresham, Special Commissioner James Blount reported on June 1, 1893, “The population of the Hawaiian Islands can but be studied by one unfamiliar with the native tongue from its several census reports. A census is taken every six years. The last report is for the year 1890. From this it appears that the whole population numbers 89,990. This number includes natives, or, to use another designation, Kanakas, half-castes (persons containing an admixture of other than native blood in any proportion with it), Hawaiian-born foreigners of all races or nationalities other than natives, Americans, British, Germans, French, Portuguese, Norwegians, Chinese, Polynesians, and other nationalities. Americans numbered 1,928; natives and half-castes, 40,612; Chinese, 15,301; Japanese, 12,360; Portuguese, 8,602; British, 1,344; Germans, 1,034; French, 70; Norwegians, 227; Polynesians, 588; and other foreigners 419. It is well at this point to say that of the 7,495 Hawaiian-born foreigners 4,117 are Portuguese, 1,701 Chinese and Japanese, 1,617 other white foreigners, and 60 of other nationalities.”

The permanent population has exceedingly increased since the 1890 census and according to the last census in 2011 by the United States that number was at 1,374,810. International law, however, protects the status quo of the national population of an occupied State during occupation. According to Professor von Glahn, The Occupation of Enemy Territory: A Commentary on the Law and Practice of Belligerent Occupation (1957), p. 60, “the nationality of the inhabitants of occupied areas does not ordinarily change through the mere fact that temporary rule of a foreign government has been instituted, inasmuch as military occupation does not confer de jure sovereignty upon an occupant. Thus under the laws of most countries, children born in territory under enemy occupation possess the nationality of their parents, that is, that of the legitimate sovereign of the occupied area.” Any individual today who is a direct descendent of a person who lawfully acquired Hawaiian citizenship prior to the U.S. occupation that began at noon on August 12, 1898, is a Hawaiian subject. Hawaiian law recognizes all others who possess the nationality of their parents as part of the alien population.

B. Defined Territory

According to Judge Huber, in the Island of Palmas arbitration case, “Territorial sovereignty…involves the exclusive right to display the activities of a State.” Crawford, p. 56, also states, “Territorial sovereignty is not ownership of but governing power with respect to territory.”

§6 of the Compiled Laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom states, “The laws are obligatory upon all persons, whether subjects of this kingdom, or citizens or subjects of any foreign State, while within the limits of this kingdom, except so far as exception is made by the laws of nations in respect to Ambassadors or others. The property of all such persons, while such property is within the territorial jurisdiction of this kingdom, is also subject to the laws.”

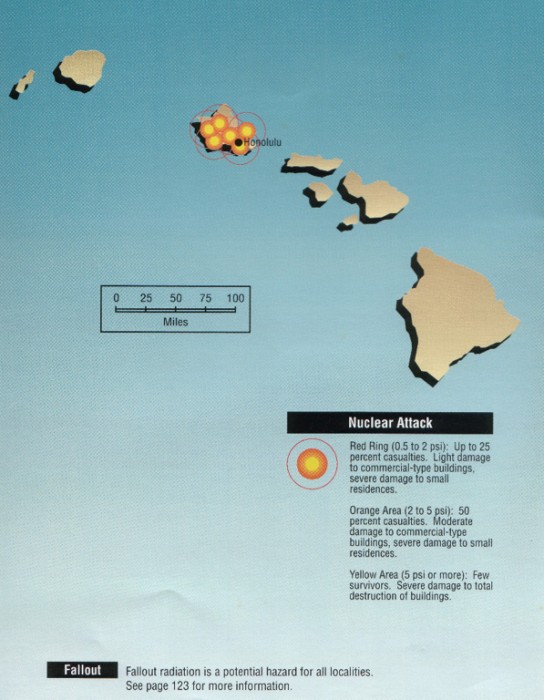

The Islands constituting the defined territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom on January 17, 1893, together with its territorial seas whereby the channels between adjacent Islands are contiguous, its exclusive economic zone of two hundred miles, and its air space, include:

Island: Location: Square Miles/Acreage:

Hawai‘i 19º 30′ N 155º 30′ W 4,028.2 / 2,578,048

Maui 20º 45′ N 156º 20′ W 727.3 / 465,472

O‘ahu 21º 30′ N 158º 00′ W 597.1 / 382,144

Kaua‘i 22º 03′ N 159º 30′ W 552.3 / 353,472

Molokai 21º 08′ N 157º 00′ W 260.0 / 166,400

Lana‘i 20º 50′ N 156º 55′ W 140.6 / 89,984

Ni‘ihau 21º 55′ N 160º 10′ W 69.5 / 44,480

Kaho‘olawe 20º 33′ N 156º 35′ W 44.6 / 28,544

Nihoa 23º 06′ N 161º 58′ W 0.3 / 192

Molokini 20º 38′ N 156º 30′ W 0.04 / 25.6

Lehua 22º 01′ N 160º 06′ W 0.4 / 256

Ka‘ula 21º 40′ N 160º 32′ W 0.2 / 128

Laysan 25º 50′ N 171º 50′ W 1.6 / 1,024

Lisiansky 26º 02′ N 174º 00′ W 0.6 / 384

Palmyra 05º 52′ N 162º 05′ W 4.6 / 2,944

Ocean 28º 25′ N 178º 25′ W 0.4 / 256

TOTAL: 6,427.74 (square miles) / 4,113,753.6 (acres)

C. Government

According to Crawford, p. 56, “Governmental authority is the basis for normal inter-State relations; what is an act of a State is defined primarily by reference to its organs of government, legislative, executive or judicial.” Since 1864, the Hawaiian Kingdom fully adopted the separation of powers doctrine in its constitution, being the cornerstone of constitutional governance.

Article 20, Hawaiian Constitution. The Supreme Power of the Kingdom in its exercise, is divided into the Executive, Legislative, and Judicial; these shall always be preserved distinct, and no Judge of a Court of Record shall ever be a member of the Legislative Assembly.

Article 31, Hawaiian Constitution. To the King belongs the executive power.

Article 45, Hawaiian Constitution. The Legislative power of the Three Estates of this Kingdom is vested in the King, and the Legislative Assembly; which Assembly shall consist of the Nobles appointed by the King, and of the Representatives of the People, sitting together.

Article 66, Hawaiian Constitution. The Judicial Power shall be divided among the Supreme Court and the several Inferior Courts of the Kingdom, in such manner as the Legislature may, from time to time, prescribe, and the tenure of office in the Inferior Courts of the Kingdom shall be such as may be defined by the law creating them.

1. Power to Declare and Wage War & to Conclude Peace

The power to declare war and to conclude peace is constitutionally vested in the office of the Monarch pursuant to Article 26, Hawaiian Constitution, “The King is the Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy, and for all other Military Forces of the Kingdom, by sea and land; and has full power by himself, or by any officer or officers he may judge best for the defense and safety of the Kingdom. But he shall never proclaim war without the consent of the Legislative Assembly.”

2. To Maintain Diplomatic Ties with Other Sovereigns

Maintaining diplomatic ties with other States is vested in the office of the Monarch pursuant to Article 30, Hawaiian Constitution, “It is the King’s Prerogative to receive and acknowledge Public Ministers…” The officer responsible for maintaining diplomatic ties with other States is the Minister of Foreign Affairs whose duty is “to conduct the correspondence of [the Hawaiian] Government, with the diplomatic and consular agents of all foreign nations, accredited to this Government, and with the public ministers, consuls, and other agents of the Hawaiian Islands, in foreign countries, in conformity with the law of nations, and as the King shall from time to time, order and instruct.” §437, Compiled Laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom. The Minister of Foreign Affairs shall also “have the custody of all public treaties concluded and ratified by the Government; and it shall be his duty to promulgate the same by publication in the government newspaper. When so promulgated, all officers of this government shall be presumed to have knowledge of the same.” §441, Compiled Laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

3. To Acquire Territory by Discovery or Occupation

Between 1822 and 1886, the Hawaiian Kingdom exercised the power of discovery and occupation that added five additional islands to the Hawaiian Domain. By direction of Ka‘ahumanu in 1822, Captain William Sumner took possession of the Island of Nihoa. On May 1, 1857; Laysan Island was taken possession by Captain John Paty for the Hawaiian Kingdom; on May 10, 1857 Captain Paty also took possession of Lysiansky Island; Palmyra Island was taken possession of by Captain Zenas Bent on April 15, 1862; and Ocean Island was acquired September 20, 1886, by proclamation of Colonel J.H. Boyd.

4. To Make International Agreements and Treaties and Maintain Diplomatic Relations with other States

Article 29, Hawaiian Constitution, provides, “The King has the power to make Treaties. Treaties involving changes in the Tariff or in any law of the Kingdom shall be referred for approval to the Legislative Assembly.” As a result of the United States of America’s recognition of Hawaiian independence, the Hawaiian Kingdom entered into a Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation, Dec. 20, 1849; Treaty of Commercial Reciprocity, Jan. 13, 1875; Postal Convention Concerning Money Orders, Sep. 11, 1883; and a Supplementary Convention to the 1875 Treaty of Commercial Reciprocity, Dec. 6, 1884.

The Hawaiian Kingdom also entered into treaties with Austria-Hungary (now separate States), June 18, 1875; Belgium, October 4, 1862; Denmark, October 19, 1846; France, September 8, 1858; Germany, March 25, 1879; the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, March 26, 1846; Italy, July 22, 1863; Japan, August 19, 1871, January 28, 1886; Netherlands, October 16, 1862; Portugal, May 5, 1882; Russia, June 19, 1869; Spain, October 9, 1863; Sweden-Norway (now separate States), April 5, 1855; and Switzerland, July 20, 1864.

Foreign Legations accredited to the Court of the Hawaiian Kingdom in the city of Honolulu included the United States of America, Portugal, Great Britain, France and Japan.

Foreign Consulates in the Hawaiian Kingdom included the United States of America, Italy, Chile, Germany, Sweden-Norway, Denmark, Peru, Belgium, Netherlands, Spain, Austria-Hungary, Russia, Great Britain, Mexico and China.

Hawaiian Legations accredited to foreign States included the United States of America in the city of Washington, D.C.; Great Britain in the city of London; France in the city of Paris, Russia in the city of Saint Petersburg; Peru in the city of Lima; and Chile in the city of Valparaiso.

Hawaiian Consulates in foreign States included the United States of America in the cities of New York, San Francisco, Philadelphia, San Diego, Boston, Portland, Port Townsend and Seattle; Mexico in Mexico city and the city of Manzanillo; Guatemala; Peru in the city of Callao; Chile in the city of Valparaiso; Uruguay in the city of Monte Video; Philippines (former Spanish territory) in the city of Iloilo and Manila; Great Britain in the cities of London, Bristol, Hull, Newcastle on Tyne, Falmouth, Dover, Cardiff and Swansea, Edinburgh and Leith, Glasgow, Dundee, Queenstown, and Belfast; Ireland, in the cities of Liverpool, and Dublin; Canada (former British territory) in the cities of Toronto, Montreal, Bellville, Kingston Rimouski, St. John’s, Varmouth, Victoria, and Vancouver; Australia in the cities of Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Hobart, and Launceston; New Zealand (former British territory) in the cities of Auckland and Dunedin; China in the cities of Hong Kong and Shanghai; France in the cities of Paris, Marseilles, Bordeaux, Dijon, Libourne and Papeete; Germany in the cities of Bremen, Hamburg, Frankfort, Dresden and Karlsruhe; Austria in the city of Vienna; Spain in the cities of Barcelona, Cadiz, Valencia Malaga, Cartegena, Las Palmas, Santa Cruz and Arrecife de Lanzarote; Portugal in the cities of Lisbon, Oporto Madeira, and St. Michaels; Cape Verde (former Portuguese territory) in the city of St. Vincent; Italy in the cities of Rome, Genoa, and Palermo; Netherland in the cities of Amsterdam and Dordrecht; Belgium in the cities of Antwerp, Ghent, Liege and Bruges; Sweden in the cities of Stockholm, Lyskil, and Gothemburg; Norway in the city of Oslo (formerly known as Kristiania); Denmark in the city of Copenhagen; and Japan in the city of Tokyo.