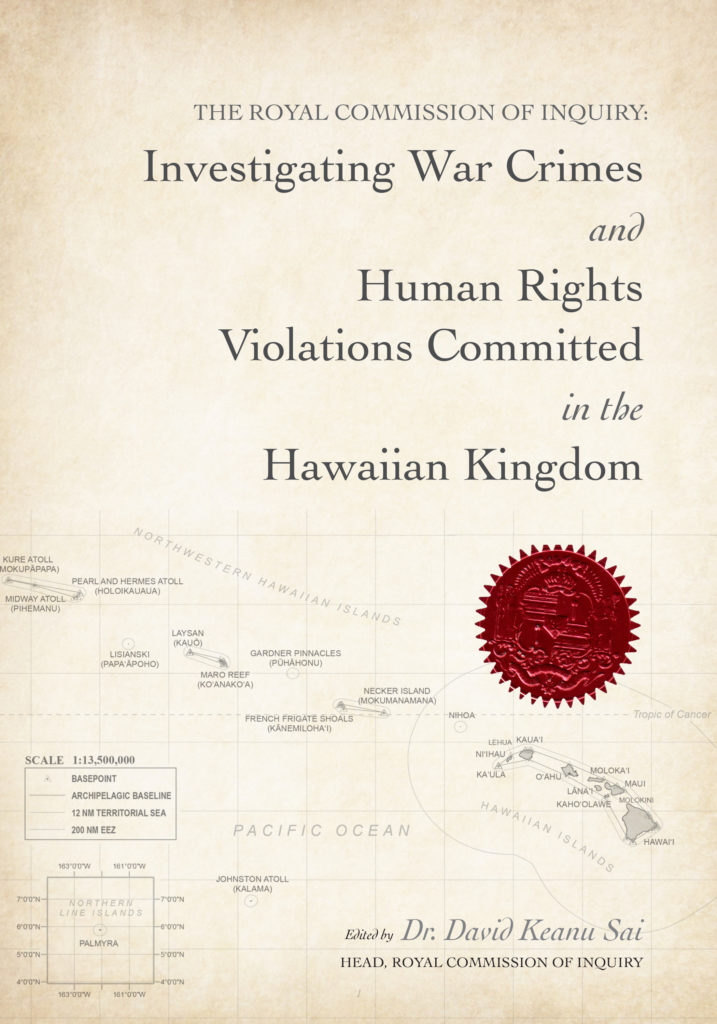

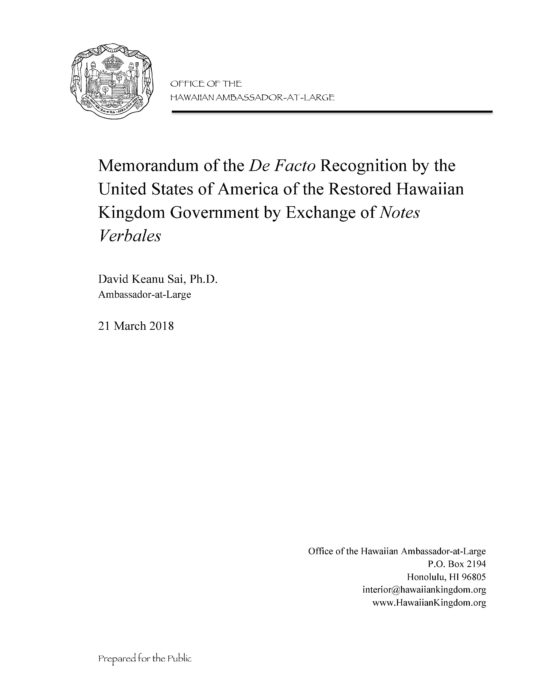

Explicit Recognition by the United States of America of the Continued Existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom and its government—the Council of Regency

HONOLULU, 5 April 2021 — On 15 March 2021, Dr. David Keanu Sai, Chairman of the Council of Regency, and Mrs. Kau‘i Sai-Dudoit, Minister of Finance, was notified that the “Securities Commission of the State of Hawaii is about to commence an enforcement action against [them] based upon the sale of unregistered Kingdom of Hawaii Exchequer Bonds, in violation of HRS § 485A-301.” In § 485A-201(2) of the statute it states that bonds issued “by a foreign government with which the United States maintains diplomatic relations” are exempt.

The State of Hawai‘i has taken the dubious position that the Council of Regency is not a government and that the Hawaiian Kingdom does not exist. This position, however, runs counter to the United States explicit recognition of the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom, as a State, and its government—the Council of Regency, when arbitral proceedings were instituted at the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) on 8 November 1999 in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom. This explicit recognition by the United States has serious consequences for the State of Hawai‘i because it triggered the Supremacy Clause under federal law, where “all treaties made, or which shall be made, under the authority of the United States, shall be the supreme law of the land; and the judges in every state shall be bound thereby, anything in the Constitution or laws of any State to the contrary notwithstanding.”

The United States Supreme Court, in United States v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp., stated that the rule of the Supremacy Clause holds “in the case of international compacts and agreements [when it forms] the very fact that complete power over international affairs is in the National Government and is not and cannot be subject to any curtailment or interference on the part of the several States.”

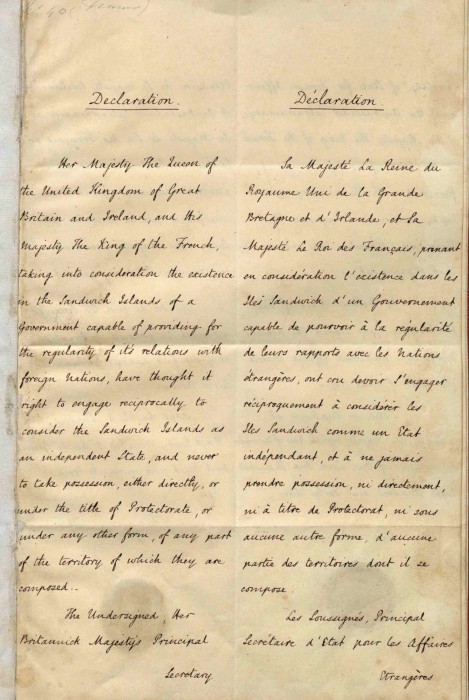

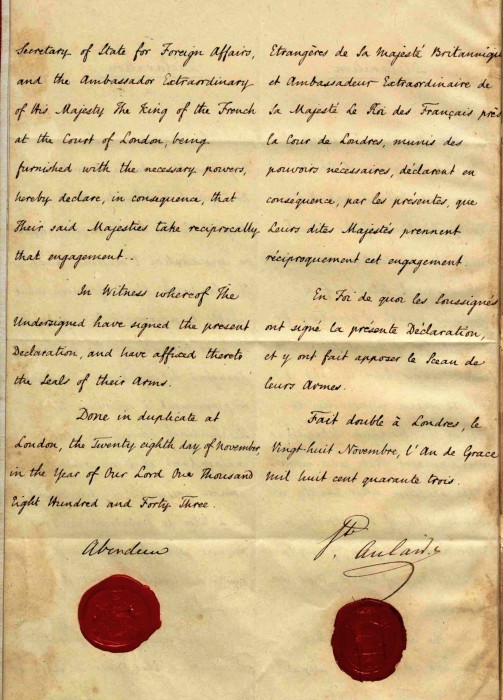

Attached to this press release is a Preliminary Report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry that explains not only the United States explicit recognition of the Council of Regency and the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom, but also by the explicit recognition by the other treaty partners of the Hawaiian Kingdom, which includes Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Great Britain, Hungary, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Russia, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland.

The Supremacy Clause has rendered the State of Hawai‘i incapacitated because under international law, congressional acts, which includes the 1959 Statehood Act, have no effect in the territory of a foreign State unless it has the consent by the government of that State. There is no consent from the Hawaiian government since 1893 that would allow American municipal laws to have any effect within the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom. This was precisely the dispute between Larsen and the Council of Regency. As the PCA stated:

Lance Paul Larsen, a resident of Hawaii, brought a claim against the Hawaiian Kingdom by its Council of Regency (“Hawaiian Kingdom”) on the grounds that the Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom is in continual violation of: (a) its 1849 Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation with the United States of America, as well as the principles of international law laid down in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 1969 and (b) the principles of international comity, for allowing the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws over the claimant’s person within the territorial jurisdiction of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

American municipal laws include the constitution and laws of the State of Hawai‘i. Under international criminal law, the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws within the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom constitutes the war crime of usurpation of sovereignty. War crimes have no statute of limitation and a person who commits a war crime can be prosecuted even after 50 years from the time the war crime was committed. Under international law, war criminals are subjected to be prosecuted by all States when they enter the State’s territory even though the crimes were committed outside of their territories. Finland and Switzerland are currently prosecuting war criminals for crimes committed in Liberia.

The only way for the State of Hawai‘i and its Counties to continue to govern is in accordance with international humanitarian law and the law of occupation. From a domestic standpoint, the Supremacy Clause renders the existence of the State of Hawai‘i unconstitutional and void because its existence is in conflict with treaties that the United States has ratified, which includes the 1849 Hawaiian-American Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation. To continue to govern would be to transform themselves into an occupying government within the limits and what is allowed under international law.

In a letter of correspondence from Dr. Sai, as Head of the Royal Commission of Inquiry (RCI), to State of Hawai‘i Attorney General Clare E. Connors, dated 2 June 2020, the Attorney General was notified that:

I am not aware whether you were informed of three meetings I had in 2015 with Mike McCartney, former chief of staff for Governor David Ige, at his office in the Executive Chambers regarding the subject of war crimes and the American occupation. This prompted a report I submitted to him that summarized what we discussed in those three meetings and how the State of Hawai‘i has a duty, under international humanitarian law, to transform itself into a Military government by virtue of Article V, section 5 of the Constitution of the State of Hawai‘i. United States practice for Military government is covered in United States Army and Navy FM 27-5, and occupation of an occupied State is covered in FM 27-10. The Adjutant General, MG Kenneth Hara, should be aware of these regulations and the function of a Military government.

…

These are not normal times but you are the legal advisor to the Governor, and due to the severity of the situation under international criminal law and the material elements of mens rea and actus reus, I respectfully implore you to carefully review the information I have provided you and to advise the office of the Governor accordingly. Under international humanitarian law, decisions on this matter are not with the federal government nor is it with its military here in the islands, but solely on the shoulders of the State of Hawai‘i as it is the entity in effective control of Hawaiian territory thereby triggering the law of occupation. I should also note that the governmental infrastructure of the State of Hawai‘i is that of the Hawaiian Kingdom. The only change was in name, e.g. the Department of Land and Natural Resources is the Ministry of the Interior. All that was changed in 1893 was the Queen and her cabinet, and the top law enforcement of the kingdom, being forcibly replaced by insurgents calling themselves the Executive and Advisory Councils.

Both the National Lawyers Guild (NLG) and the International Association of Democratic Lawyers (IADL) have called upon the State of Hawai‘i to transform itself into an occupying government. In its letter to Governor David Ige of 10 November 2020, the NLG stated:

We urge you, Governor Ige, to proclaim the transformation of the State of Hawai‘i and its Counties into an occupying government pursuant to the Council of Regency’s proclamation of June 3, 2019, in order to administer the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom. This would include carrying into effect the Council of Regency’s proclamation of October 10, 2014 that bring the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom in the nineteenth century up to date. We further urge you and other officials of the State of Hawai‘i and its Counties to familiarize yourselves with the contents of the recent eBook published by the RCI and its reports that comprehensively explains the current situation of the Hawaiian Islands and the impact that international humanitarian law and human rights law have on the State of Hawai‘i and its inhabitants.”

In its resolution of 7 February 2021, the “IADL fully supports the NLG’s November 10, 2020 letter to State of Hawai‘i Governor David Ige urging him to ‘proclaim the transformation of the State of Hawai‘i and its Counties into an occupying government pursuant to the Council of Regency’s proclamation of June 3, 2019, in order to administer the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom. This would include carrying into effect the Council of Regency’s proclamation of October 10, 2104 that bring the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom in the nineteenth century up to date.”

The NLG letter and the IADL resolution are attached to this press release.

The actions taken by the State of Hawai‘i against government officials of the Hawaiian Kingdom also constitutes a violation of Article 54 of the Fourth Geneva Convention, which states, “The Occupying Power may not alter the status of public officials…in the occupied territories, or in any way apply sanctions to or take any measures of coercion or discrimination against the them.” The Fourth Geneva Convention was ratified by the United States Senate on 6 July 1955 and came into force on 2 February 1956. As such, the Fourth Geneva Convention comes under the Supremacy Clause.

In light of the awareness of the occupation by the leadership of the State of Hawai‘i, these allegations against the Hawaiian government officials constitute malicious intent. As pointed out by Professor Lenzerini, under the rules of international law, “the working relationship between the Regency and the administration of the occupying State would have the form of a cooperative relationship aimed at guaranteeing the realization of the rights and interests of the civilian population and the correct administration of the occupied territory.” This unwarranted attack is a violation of the law of occupation, and as a proxy for the United States, it also constitutes an international wrongful act.

###