Under international humanitarian law, which includes the law of occupation and the protection afforded civilians who are not engaged in war, denationalization is not only a war crime but is synonymous with the term genocide. Since the occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom began during the Spanish-American War, the United States embarked on a deliberate campaign of forced denationalization in order to conceal the occupation and militarization of a neutral State. Denationalization, in its totality, is genocide.

Prior to World War I, violations of international law did not include war crimes, or, in other words, crimes where individuals, as separate and distinct from the State or country, could be prosecuted and where found guilty be punished, which included the death penalty. The Commission on the Responsibility of the Authors of the War and on Enforcement of Penalties (Commission on Responsibility) of the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 took up the matter of war crimes after World War I (1914-1918). The Commission identified 32 war crimes, one of which was “attempts to denationalize the inhabitants of occupied territory.”

Although the 1907 Hague Convention, IV, did not specify the term “denationalization” as a war crime, the Commission on Responsibility relied on the preamble of the 1899 Hague Convention, II, which states, “Until a more complete code of the laws of war is issued, the High Contracting Parties think it right to declare that in cases not included in the Regulations adopted by them, populations and belligerents remain under the protection and empire of the principles of international law, as they result from the usages established between civilized nations, from the laws of humanity and the requirements of the public conscience.” This preamble has been called the Martens clause, which was based on a declaration read by the Russian delegate, Professor von Martens, at the Hague Peace Conference in 1899.

In October of 1943, the United States, the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union established the United Nations War Crimes Commission (UNWCC). World War II had been waging since 1939, and atrocities committed by Germany, Italy and Japan drew the attention of the Allies to hold individuals responsible for the commission of war crimes. On December 2, 1943, the UNWCC adopted by resolution the list of war crimes that were drawn up by the Commission on Responsibility in 1919 with the addition of another war crime—indiscriminate mass arrests. The UNWCC was organized into three Committees: Committee I (facts and evidence), Committee II (enforcement), and Committee III (legal matters).

Committee III was asked to draft a report expanding on the war crime of “denationalization” and its criminalization under international law. Committee III did not rely solely on the Martens clause as the Commission on Responsibility did in 1919, but rather used it as an aid to interpret the articles of the 1907 Hague Convention, IV. It, therefore, concluded that “attempts to denationalize the inhabitants of occupied territory” violated Article 43, where the occupying State must respect the laws of the occupied State; Article 46, where family honor and rights and individual life must be respected; and Article 56, where the property of institutions dedicated to education is protected.

In 1944, Professor Raphael Lemkin first coined the term “genocide” in his publication Axis Rule in Occupied Europe (p. 79-95). The term is a combination of the Greek word genos (race or tribe) and the Latin word cide (killing). The 1919 Commission on Responsibility did list “murders and massacres; systematic terrorism” as war crimes, but Professor Lemkin’s definition of genocide was much broader and more encompassing.

According to Professor Lemkin, “Generally speaking, genocide does not necessarily mean the immediate destruction of a nation, except when accomplished by mass killings of all members of a nation. It is intended rather to signify a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves. The objectives of such a plan would be disintegration of the political and social institutions, of culture, language, national feelings, religion, and the economic existence of national groups, and the destruction of the personal security, liberty, health, dignity, and even the lives of the individuals belonging to such groups.”

According to Professor Lemkin, “Generally speaking, genocide does not necessarily mean the immediate destruction of a nation, except when accomplished by mass killings of all members of a nation. It is intended rather to signify a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves. The objectives of such a plan would be disintegration of the political and social institutions, of culture, language, national feelings, religion, and the economic existence of national groups, and the destruction of the personal security, liberty, health, dignity, and even the lives of the individuals belonging to such groups.”

“Genocide has two phases,” argued Professor Lemkin, “one, destruction of the national pattern of the oppressed group; the other, the imposition of the national pattern of the oppressor. This imposition, in turn, may be made upon the oppressed population which is allowed to remain, or upon the territory alone, after removal of the population and the colonization of the area by the oppressor’s own nationals. Denationalization was the word used in the past to describe the destruction of a national pattern.” Professor Lemkin believed that denationalization was inadequate and should be replaced with genocide.

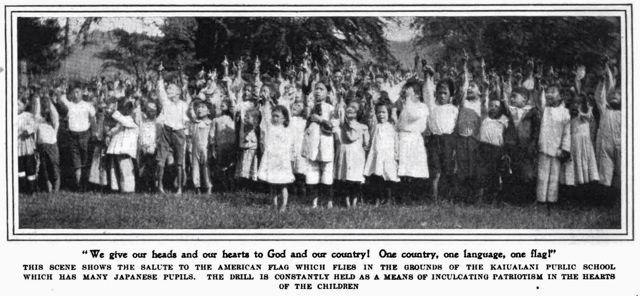

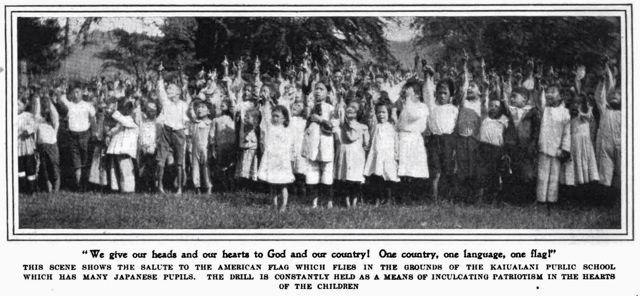

The term genocide, however, was not a war crime under international humanitarian law at the time, but it appears that Committee III was in agreement with Professor Lenkin that it should be a war crime. The problem that faced Committee III was how to categorize genocide as a war crime under the Hague Convention, IV. On September 27, 1945, Committee III argued that denationalization was not a single act of “depriving the inhabitants of the occupied territory of their national characteristics,” but rather a program that attempted to achieve this result through: “interference with the methods of education; compulsory education in the language of the occupant; … the ban on the using of the national language in schools, streets and public places; the ban on the national press and on the printing and distributing of books in the language of the occupied region; the removal of national symbols and names, both personal and geographical; [and] interference with religious services as far as they have a national peculiarity.”

Committee III also argued that denationalization included other activities such as: “compulsory or automatic granting of the citizenship of the occupying Power; imposing the duty to swearing the oath of allegiance to the occupant; the introduction of the administrative and judicial system of the occupying Power, the imposition of its financial, economic and labour administration, the occupation of administrative offices by nationals of the occupying Power; compulsion to join organizations and associations of the occupying Power; colonization of the occupied territory by nationals of the occupant, exploitation and pillage of economic resources, confiscation of economic enterprises, permeation of the economic life through the occupying State or individuals of the nationality of the occupant.”

Committee III also stated that these activities by the occupying State or its nationals would also “fall under other headings of the list of war crimes.”

There were apparent similarities between Professor Lemkin’s definition of genocide and the Committee III’s definition of denationalization. Professor Lemkin argued that genocide was more than just mass murder of a particular group of people, but “the specific losses of civilization in the form of the cultural contributions which can only be made by groups of people united through national, racial or cultural characteristics (Lemkin, Genocide as a Crime under International Law, 41 AJIL (1947) 145, at 147).” Similarly, Committee III argued that denationalization “kill[s] the soul of the nation,” and was “the counterpoint to the physical act of killing the body, which was ordinary murder (Preliminary Report of the Chairman of Committee III, C.148, 28 Sept. 1945, 6/34/PAG-3/1.1.0, at 2).”

In its October 4, 1945 report “Criminality of Attempts to Denationalise the Inhabitants of Occupied Territory,” Committee III renamed denationalization to be genocide.

On December 11, 1946, the General Assembly of the United Nations adopted a resolution that declared genocide a crime under the existing international law and recommended member States to sign a convention. After two years of study, the General Assembly adopted the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide on December 9, 1948. By the Convention, genocide has been recognized as a crime even when there is no war or the occupation of a State. Genocide became an international crime along with piracy, drug trafficking, arms trafficking, human trafficking, money laundering and smuggling of cultural artifacts. During war or the occupation of a State, genocide is synonymous with the war crime of denationalization.

In the Trial of Ulrich Greifelt and Others (October 10, 1947-March 10, 1948) at Nuremberg, the United States Military Tribunal asserted Committee III’s interpretation that genocide can be committed through the war crime of denationalization. In its decision, the Tribunal concluded that, “genocide…may be perpetuated through acts representing war crimes. Among these cases are those coming within the concept of forced denationalisation (p. 42).”

The Tribunal explained, “In the list of war crimes drawn up by the 1919 Commission on the Responsibility of the Authors of the War and on Enforcement of Penalties, there were included as constituting war crimes ‘attempts to denationalize the inhabitants of occupied territory.’ Attempts of this nature were recognized as a war crime in view of the German policy in territories annexed by Germany in 1914, such as in Alsace and Lorraine. At that time, as during the war of 1939-1945, inhabitants of an occupied territory were subjected to measures intended to deprive them of their national characteristics and to make the land and population affected a German province (p. 42).”

When the Hawaiian Kingdom was occupied during the Spanish-American War, the United States operated in complete disregard to the recognized principles of the law of occupation at the time. Instead of administering the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom, being the occupied State, the United States imposed its own laws, administration, judiciary and economic life throughout the Hawaiian Islands in violation of Hawaiian independence and sovereignty. According to Professor Limken, this action taken by the United States would be considered as “the imposition of the national pattern of the oppressor,” which is the second phase of genocide after the national pattern of the occupied State had been destroyed under the first phase.

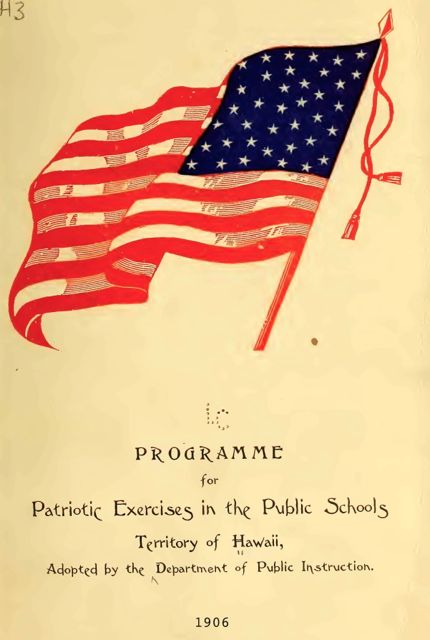

In other words, the actions taken by the United States was precisely what the Axis Powers did in occupied territories during World War I and II, which, according to Committee III, included “interference with the methods of education; compulsory education in the language of the occupant; … the ban on the using of the national language in schools, streets and public places; the ban on the national press and on the printing and distributing of books in the language of the occupied region; the removal of national symbols and names, both personal and geographical; [and] interference with religious services as far as they have a national peculiarity. [As well as] compulsory or automatic granting of the citizenship of the occupying Power; imposing the duty to swearing the oath of allegiance to the occupant; the introduction of the administrative and judicial system of the occupying Power, the imposition of its financial, economic and labour administration, the occupation of administrative offices by nationals of the occupying Power; compulsion to join organizations and associations of the occupying Power; colonization of the occupied territory by nationals of the occupant, exploitation and pillage of economic resources, confiscation of economic enterprises, permeation of the economic life through the occupying State or individuals of the nationality of the occupant.”

Under Hawaiian law, native (aboriginal ) Hawaiians had universal health care at no charge through the Queen’s Hospital, which received funding from the Hawaiian Kingdom legislature. Early into the occupation, however, American authorities stopped the funding in 1904, because they asserted that the collection of taxes used to benefit a particular ethnic group violated American law. In a legal opinion by the Territorial Government’s Deputy Attorney General E.C. Peters on January 7, 1904, to the President of the Board of Health, Peters stated, “I am consequently of the opinion that the appropriation of the sum of $30,000.00 for the Queen’s Hospital is not within the legitimate scope of legislative authority.”

Since 1904, aboriginal Hawaiians had to pay for their healthcare from an institution that was established specifically for them at no charge. According to the International Criminal Court’s (ICC) Elements of Crimes, one of the elements of the international crime of “Genocide by deliberately inflicting condition of life calculated to bring about physical destruction,” is that the “conditions of life were calculated to bring about the physical destruction of that group, in whole or in part.” The ICC recognizes the term “conditions of life” includes, “but is not necessarily restricted to, deliberate deprivation of resources indispensable for survival, such as food or medical services, or systematic expulsion from homes.”

As a result of the “deliberate deprivation of…medical services,” many aboriginal Hawaiians could not afford medical care in their own country, which has led to the following dire health statistics today.

- 13.4% of aboriginal Hawaiians who were surveyed in 2013 reported that they do not have any kind of health care coverage, which is the highest rate across all ethnic groups surveyed (Nguyen & Salvail, Hawaii Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, State of Hawai‘i Department of Health).

- Aboriginal Hawaiians are dying at younger ages amongst all other ethnicities, with rates 40% higher when compared to Caucasians (Panapasa, Mau, Williams & McNally, Mortality patters of Native Hawaiians across their lifespan: 1990-2000, 100(11) American Journal of Public Health 2304-10 (2010); and Ka‘opua, Braun, Browne, Mokuau & Park, Why are Native Hawaiians underrepresented in Hawai‘i’s older adult population? Exploring social and behavioral factors of longevity, Journal of Aging Research (2011).

- Aboriginal Hawaiians have the highest rate of diabetes in the Hawaiian Islands (Crabbe, Eshima, Fox, & Chan (2011), Native Hawaiian Health Fact Sheet 2011, Office of Hawaiian Affairs, Demography Section, Research Division).

- 5% of aboriginal Hawaiians are overweight, which is higher than any other ethnic group in the Hawaiian Islands (Nguyen & Salvail, 2013).

- 7% of aboriginal Hawaiians have high blood pressure, being second only to Japanese at 39.7% (Nguyen & Salvail, 2013).

- Aboriginal Hawaiians are more likely to have chronic diseases than non-aboriginal Hawaiians (Nguyen & Salvail, 2013).

- 48% of the deaths of aboriginal Hawaiian children occur during the perinatal period (Crabbe et al., 2011).

- 7% of aboriginal Hawaiian adults report being diagnosed with a depressive disorder (Nguyen & Salvail, 2013).

Professor Lemkin would view these statistics as connoting “the destruction of the biological structure” of aboriginal Hawaiians, which is the outcome of the second phase of genocide where the imposition of the national pattern of the oppressor has been established. In addition to these statistics are added the deaths of aboriginal Hawaiians who died in the wars of the United States after forced conscription into the Armed Forces and their compulsion to swear allegiance. These wars included World War I, World War II, the Korean War and the Vietnam War.

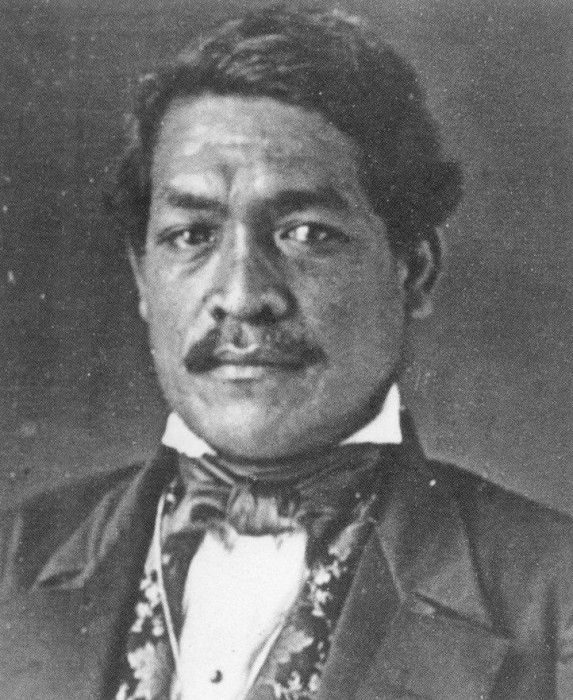

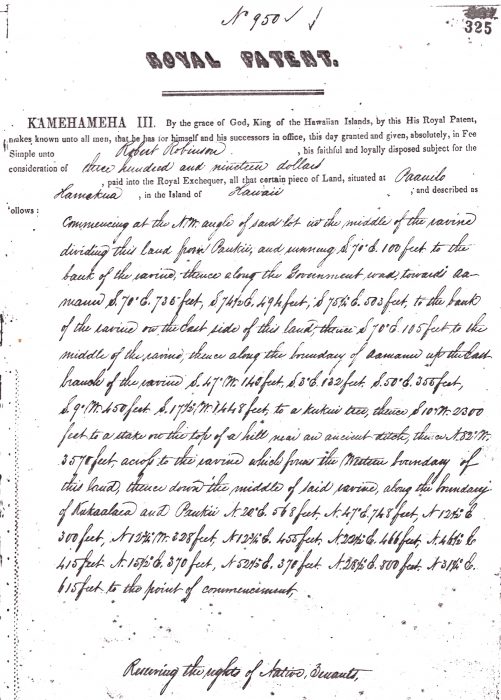

In 1839, King Kamehameha III proclaimed, by Declaration, the protection for both person and property in the kingdom by stating, “Protection is hereby secured to the persons of all the people; together with their lands, their building lots, and all their property, while they conform to the laws of the kingdom, and nothing whatever shall be taken from any individual except by express provision of the laws.” The Hawaiian Legislature, by resolution passed on October 26, 1846, acknowledged that the 1839 Declaration of Rights recognized “three classes of persons having vested rights in the lands,—1st, the government, 2nd, the landlord [Chiefs and Konohikis], and 3d, the tenant [natives] (Principles adopted by the Board of Commissioners to Quiet Land Titles, in their Adjudication of Claims Presented to Them, Resolution of the Legislative Council, Oct. 26, 1846).” Furthermore, the Legislature also recognized that the Declaration of 1839 “particularly recognizes [these] three classes of persons as having rights in the sale,” or revenue derived from the land as well.

In 1839, King Kamehameha III proclaimed, by Declaration, the protection for both person and property in the kingdom by stating, “Protection is hereby secured to the persons of all the people; together with their lands, their building lots, and all their property, while they conform to the laws of the kingdom, and nothing whatever shall be taken from any individual except by express provision of the laws.” The Hawaiian Legislature, by resolution passed on October 26, 1846, acknowledged that the 1839 Declaration of Rights recognized “three classes of persons having vested rights in the lands,—1st, the government, 2nd, the landlord [Chiefs and Konohikis], and 3d, the tenant [natives] (Principles adopted by the Board of Commissioners to Quiet Land Titles, in their Adjudication of Claims Presented to Them, Resolution of the Legislative Council, Oct. 26, 1846).” Furthermore, the Legislature also recognized that the Declaration of 1839 “particularly recognizes [these] three classes of persons as having rights in the sale,” or revenue derived from the land as well. By definition, a

By definition, a

In December 2014,

In December 2014,  Before the re-filing, Dr. Sai met with Governor David Ige’s

Before the re-filing, Dr. Sai met with Governor David Ige’s

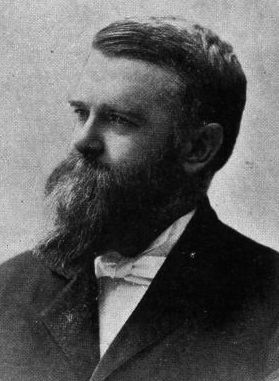

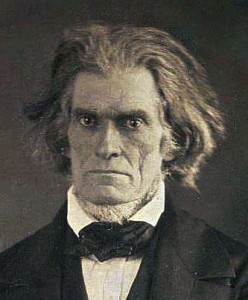

Senator Augustus Bacon, stated, “The proposition which I propose to discuss is that a measure which provides for the annexation of foreign territory is necessarily, essentially, the subject matter of a treaty, and that the assumption of the House of Representatives in the passage of the bill and the proposition on the part of the Foreign Relations Committee that the Senate shall pass the bill, is utterly without warrant in the Constitution [31 Cong. Rec. 6145 (June 20, 1898)].”

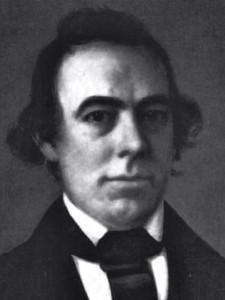

Senator Augustus Bacon, stated, “The proposition which I propose to discuss is that a measure which provides for the annexation of foreign territory is necessarily, essentially, the subject matter of a treaty, and that the assumption of the House of Representatives in the passage of the bill and the proposition on the part of the Foreign Relations Committee that the Senate shall pass the bill, is utterly without warrant in the Constitution [31 Cong. Rec. 6145 (June 20, 1898)].” Senator William Allen stated, “A Joint Resolution if passed becomes a statute law. It has no other or greater force. It is the same as if it would be if it were entitled ‘an act’ instead of ‘A Joint Resolution.’ That is its legal classification. It is therefore impossible for the Government of the United States to reach across its boundary into the dominion of another government and annex that government or persons or property therein. But the United States may do so under the treaty making power [31 Cong. Rec. 6636 (July 4, 1898)].”

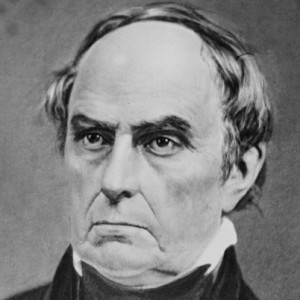

Senator William Allen stated, “A Joint Resolution if passed becomes a statute law. It has no other or greater force. It is the same as if it would be if it were entitled ‘an act’ instead of ‘A Joint Resolution.’ That is its legal classification. It is therefore impossible for the Government of the United States to reach across its boundary into the dominion of another government and annex that government or persons or property therein. But the United States may do so under the treaty making power [31 Cong. Rec. 6636 (July 4, 1898)].” Senator Thomas Turley stated, “The Joint Resolution itself, it is admitted, amounts to nothing so far as carrying any effective force is concerned. It does not bring that country within our boundaries. It does not consummate itself [31 Cong. Rec. 6339 (June 25, 1898)].”

Senator Thomas Turley stated, “The Joint Resolution itself, it is admitted, amounts to nothing so far as carrying any effective force is concerned. It does not bring that country within our boundaries. It does not consummate itself [31 Cong. Rec. 6339 (June 25, 1898)].” speak to me of a ‘treaty’ when we are confronted with a mere proposition negotiated between the plenipotentiaries of two

speak to me of a ‘treaty’ when we are confronted with a mere proposition negotiated between the plenipotentiaries of two The Hawaiian government selected Professor

The Hawaiian government selected Professor

Ms. Ninia Parks, counsel for Lance Larsen, selected

Ms. Ninia Parks, counsel for Lance Larsen, selected  Once Mr. Agard was able to confirm the selections with the PCA, these two arbitrators would recommend a person to be the president of the tribunal. Both Greenwood and Griffith nominated Professor

Once Mr. Agard was able to confirm the selections with the PCA, these two arbitrators would recommend a person to be the president of the tribunal. Both Greenwood and Griffith nominated Professor

As part of the International Bureau’s due diligence into the status of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State under international law, the PCA’s Secretary General Van Den Hout made a formal recommendation to David Keanu Sai, Agent for the Hawaiian Government, to provide a formal invitation to the United States to join in the arbitration proceedings. This would have one of three outcomes—first, the United States would dispute the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State and the PCA would terminate the proceedings, second, it could join the arbitration in order to answer Larsen’s allegations of violating his rights that led to his incarceration, or, third, it could refuse to join in the arbitration, but allow it to go forward.

As part of the International Bureau’s due diligence into the status of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State under international law, the PCA’s Secretary General Van Den Hout made a formal recommendation to David Keanu Sai, Agent for the Hawaiian Government, to provide a formal invitation to the United States to join in the arbitration proceedings. This would have one of three outcomes—first, the United States would dispute the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State and the PCA would terminate the proceedings, second, it could join the arbitration in order to answer Larsen’s allegations of violating his rights that led to his incarceration, or, third, it could refuse to join in the arbitration, but allow it to go forward. In a conference call held in Washington, D.C., on March 3, 2000,

In a conference call held in Washington, D.C., on March 3, 2000,  between Mr. John Crook, United States Assistant Legal Adviser for United Nations Affairs, Ms. Parks and Mr. Sai, the United States was formally invited to join in the arbitration. It wasn’t until a couple of weeks later that the United States Embassy in The Hague notified the PCA that the United States will not join in the arbitration, but asked permission of the Hawaiian Government and Mr. Larsen’s attorney to have access to all pleadings, transcripts and records. The United States took the third option and did not deny the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State.

between Mr. John Crook, United States Assistant Legal Adviser for United Nations Affairs, Ms. Parks and Mr. Sai, the United States was formally invited to join in the arbitration. It wasn’t until a couple of weeks later that the United States Embassy in The Hague notified the PCA that the United States will not join in the arbitration, but asked permission of the Hawaiian Government and Mr. Larsen’s attorney to have access to all pleadings, transcripts and records. The United States took the third option and did not deny the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State.

After written pleadings were submitted, oral hearings were held at The Hague on December 7, 8, and 11, 2000, and the Arbitration Award was filed with the PCA on February 5, 2001. The court concluded that the United States was a necessary third party and without their participation in the arbitration proceedings, Mr. Larsen’s allegations of negligence against the Hawaiian Government could not move forward.

After written pleadings were submitted, oral hearings were held at The Hague on December 7, 8, and 11, 2000, and the Arbitration Award was filed with the PCA on February 5, 2001. The court concluded that the United States was a necessary third party and without their participation in the arbitration proceedings, Mr. Larsen’s allegations of negligence against the Hawaiian Government could not move forward.