ANNEXATION OF THE HAWAIIAN ISLANDS

(House Committee on Foreign Affairs Report to accompany H. Res. 259, May 17, 1898 (House Report no. 1355, 55th Congress, 2d session)

May 17, 1898.—Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the state of the Union and ordered to be printed.

Mr. Hitt, from the U.S. Congress House Committee on Foreign Affairs, submitted the following

REPORT.

[To accompany H. Res. 259.]

The joint resolution (H. Res. 259) provides for the annexation of the Hawaiian Islands to the United States. The proposition is not new either to the Government of the little Commonwealth in the Pacific, to the United States, or to other nations. It has been apparent for more than fifty years that so small and feeble a Government could not maintain its independence, and that it must ultimately be merged into a greater power. It has been repeatedly seized and Honolulu occupied, and has repeatedly made overtures to the United States to be united with us. In 1829 the French commander, Laplace, seized Honolulu and held it for awhile, after forcing upon the government a harsh treaty. In 1843 it was seized by the British commander, Lord Pawlet, but subsequently released by Great Britain upon the remonstrances of other powers. It was again seized by the French in 1849 and held for a considerable time, but was evacuated after diplomatic pressure from England and the United States.

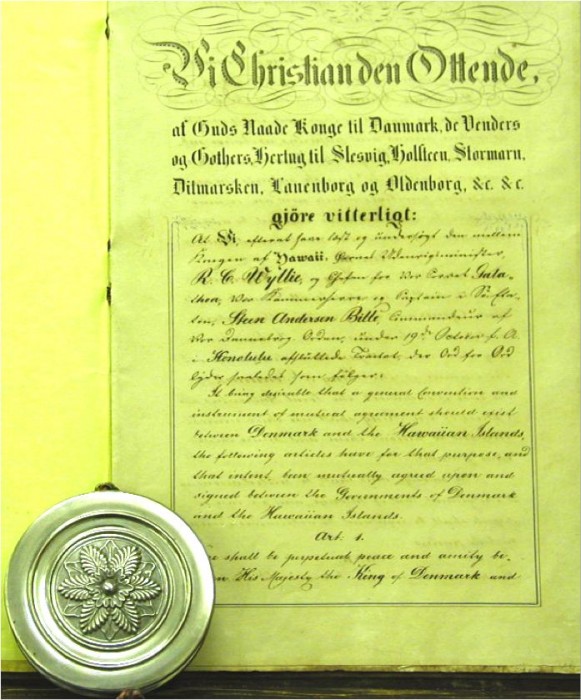

In 1851 the King, pressed by his perplexities with France and England, delivered to our commissioner a deed of cession of the islands to the United States, to be held until a satisfactory adjustment had been reached with France, and failing that, permanently. In 1854 our Secretary of State, Mr. Marcy, authorized the negotiation of an annexation treaty. The King made a draft satisfactory to him and modifying the one proposed, but before the conclusion was reached he died. In 1893 a treaty was negotiated between our government and that of the Hawaiian Islands for the annexation of the islands to the United States. No word of protest was uttered by any other government. This treaty, while pending before the Senate, was withdrawn by the President, a change of administration having taken place. Again, June 16, 1897, a treaty of annexation, similar in provisions to the joint resolution now proposed, was agreed to by the government of Hawaii and duly ratified by their Senate.

There is, therefore, no undue pressure on the part of the United States as a greater power; no surprise of any one; no possibility of objections by other governments. It is simply the obvious result of the natural course of events through a long period of years thus completed with the cordial consent of the sovereign powers of both Governments. The only question involved is whether the proposed possession of the Hawaiian Islands would be advantageous to the United States.

THEIR STRATEGIC IMPORTANCE.

Recent events In the existing war with Spain have called public attention to what has long been discussed by military and naval authorities—the inestimable importance to the United States of possessing the Hawaiian Islands in case of war with any strong naval power. They lie facing our Pacific coast. Their strategic importance is vastly increased by the fact that they are separated by thousands of miles from any other and more distant group in the northern Pacific Ocean and are the only group facing our coast. In the possession of an enemy they would serve as a secure base for attacking any and all of our Pacific coast cities. In our possession they would deprive the enemy s fleet of all facilities for coaling, supplies, or repairs, and speedily paralyze all his naval operations. The first object of an enemy attacking us on that side of the Republic would be to secure these islands, and in their present condition their possession would fall to the stronger naval power.

The leading nations—England, France, Germany, Japan, Spain, and the United States—have each a Pacific Squadron. Every one of these squadrons is stronger than ours save that of Spain, which is the weakest. Had the war in which we are now engaged been with any of the other powers they might have worsted our fleet and seized the Hawaiian Islands, which are not now defended by any fortification or cannon, thus exactly reversing our recent good fortune at Manila. They would then have had a convenient base for supplies, coal, and repairs, from which to actively harry and devastate our coast. But were we in complete possession of the Hawaiian Islands and they properly prepared for defense (which eminent officers of the Army and Navy stated to the committee could be done at a cost of $500,000), our fleet, even if pressed by a greatly superior sea power, would have an impregnable refuge at Pearl Harbor, backed by a friendly population and militia, with all the resources of the large city of Honolulu and a small but fruitful country. Holding this all important strategic point, the enemy could not remain in that part of the Pacific, thousands of miles from any base, without running out of coal sufficient to get back to their own possessions. The islands would secure both our fleet and our coast.

GENERAL SCHOFIELD’S VIEW.

As General Schofield stated to the committee—

“The most important feature of all is that it economizes the naval force rather than increases it. It is capable of absolute defense by shore batteries, so that a naval fleet, after going there and replenishing its supplies and making what repairs are needed, can go away and leave the harbor perfectly safe to the protection of the army. * * * The Spanish fleet on the Asiatic station was the only one of all the fleets we could have overcome as we did. Of course, that cannot again happen, for we will not be able to pick up so weak a fellow next time. We are liable at any time to get into a war with a nation which has a more powerful fleet than ours, and it is of vital importance, therefore, if we can, to hold the point from which they can conduct operations against our Pacific coast. Especially is that true until the Nicaragua Canal is finished, because we can not send a fleet around from the Atlantic to the Pacific.”

The same eminent and experienced soldier, when asked whether it would be sufficient to have Pearl Harbor without the islands, said we ought to have the islands to hold the harbor; that if left free and neutral complications would arise with foreign nations, who would take advantage of a weak little republic with claims for damages enforced by warships, as is frequently seen. If annexed we would settle any dispute with a foreign nation; that we would be much stronger if we owned the islands as part of our territory, and would then also have the resources of the islands, which are so fertile, for military

supplies; that if we do not have the political control they may become Japanese, and we would be surrounded by a hostile people.

Admiral Walker, who has had long experience in the waters of the Hawaiian Islands, emphatically confirmed the views of General Schofield, especially that it would cost far less to protect the Pacific coast with the Hawaiian Islands than without them; that it would be taking a point of vantage instead of giving it to your enemy.

RISK OF DELAY.

We must face the future in dealing with this proposed annexation. It is impossible for the Republic of Hawaii to maintain a permanent existence preserving in force the influences which are now in the ascendant there and which are cordial and friendly to the United States. Of its mixed population of 109,000 a powerful element is Japanese—24,407—of whom 19,212 are males, almost all of them grown men, for they are not divided as ordinary populations are in the usual proportions of men, women, and children. They are a far stronger element of physical force than the native race, which has diminished until there are now only thirty-odd thousand, of whom, by the usual proportions of population, there are not over 8,000 grown men. The native Hawaiian race cannot in any contingency control the island. It must fall to some foreign people.

The Japanese are intensely Japanese, retaining their allegiance to their Empire and responding to suggestions from the Japanese officials. Very many of them served in the recent war with China. The Japanese Government not long ago demanded of the Hawaiian Government, under their construction of a treaty made in 1871, that the Japanese in the Hawaiian Islands should have equal privileges with all other persons, which would include voting and holding office. This claim was made when a flood of Japanese subjects, under the supervision of the Government of that country, of from 1,000 to 2,000 per month, were being poured into the Hawaiian Islands, threatening a speedy change of the Government into Japanese hands, and ultimately to a Japanese possession. The demand was resisted by the little Republic and a treaty of annexation with the United States arrested it for a time.

Japan protested earnestly to our government against that treaty, but our Secretary of State refused to consider their protest; yet the Japanese government has not withdrawn its demand on the Hawaiian Government, and is waiting to renew and press it with more energy and success if annexation to the United States s rejected by this Congress. It could then in a few months throw many thousands of Japanese subjects into the Hawaiian Islands, completely overwhelming all other influences.

By a clause in our reciprocity treaty with the Hawaiian Islands we have right to establish and maintain a coaling and repair station in Pearl Harbor, which is about 8 miles from the city of Honolulu, and capable of being made one of the best harbors in the world, easily fortified to make it impregnable from the sea. It is the only harbor of such a character in the whole group. We have thus far done nothing toward taking possession, fortifying, or opening the channel into the harbor, so that it is at present utterly useless, but capable of infinite possibilities.

The grant of this harbor to our Government is a part of a reciprocity treaty. After that treaty had been ratified, but before the ratification had been exchanged, the Hawaiian minister and the Secretary of State of the United States exchanged notes which declared that our rights in Pearl Harbor would cease whenever the reciprocity treaty was terminated. That treaty may be terminated upon one year’s notice by either party. It grants advantages in our markets to Hawaiian trade, and concedes to us not only the use of Pearl Harbor, but excludes any other nation from leasing a port or landing, or having any special privilege in the Hawaiian Islands, without the consent of the United States.

With the Japanese element in the ascendant and the Government under Japanese control the treaty would be promptly terminated, and with it our special rights. This would be the first step taken by that active and powerful Government toward the complete incorporation of the islands into the Japanese Empire, and their possession as a strategic point in the northern Pacific from which her strong and increasing fleet would operate. The Japanese Government is now friendly, but that would be the manifest dictate of enlightened self-interest to a wise Japanese statesman.

Annexation, and that alone, will securely maintain American control in Hawaii. Resolutions of Congress declaring our policy, or even a protectorate, will not secure it. The question of a protectorate has been successively considered by Presidents Pierce, Harrison, and McKinley in 1854, 1893, and 1897, and each time rejected because a protectorate imposes responsibility without control. Annexation imposes responsibility, but will give full power of ownership and absolute control.

AMERICAN COMMERCIAL INTERESTS.

The commercial interests of the United States, according to the declarations of our most eminent public men, would be promoted and secured by the union of the two countries. In those islands is an American colony numbering over 3,000 persons, who own practically three-fourths of all the property in the country, and, under the fostering Influence of the reciprocity treaty, trade with the United States has so increased that we now consume almost all Hawaiian exports. The people of the islands purchase from us three-fourths of all their imports, and American ships carry three-fourths of all the foreign trade of the island. American influence is ascendant in the Government, and the character of the American statesmen there in power was forcibly described by Mr. Willis, our minister to Hawaii, who was sent there by Mr. Cleveland in a spirit of hostility to them, but who was a truthful, honorable man, in these words: “They are acknowledged on all sides to be men of the highest integrity and public spirit.”

Hawaiians of American origin are energetic, intelligent, and patriotic, and are holding that outpost of Americanism against Asiatic invasion. If annexation be rejected and foreign influence gets control of the islands, our interests and commerce will fall away. The American in Hawaii looks to the United States to make purchases and there he desires to send what he exports. The Japanese merchant very naturally buys all he can in Japan, and will turn all trade there that is in his power. Our trade with the Hawaiian Islands last year amounted to $18,385,000, and with annexation practically the whole trade with the Hawaiian Islands would come to the United States, and would rapidly increase.

We have now the larger part of the shipping business, 247 American ships being employed in carrying Hawaiian trade in 1896, which would be promoted and increased by annexation. Its past prosperity has depended upon the reciprocity treaty, and if that were abrogated by a party adverse to American interests gaining control this business, like all other American interests, would fall off.

ANNEXATION WOULD END FOREIGN COMPLICATIONS.

In the struggling interests that have recently come into play in the Pacific the separate existence of the Hawaiian Government is liable at any time to raise complications with foreign governments, as in the case mentioned above of the recent interposition of Japan. An independent feeble government is a constant temptation to powerful nations, in the stress of contending interests, to intermeddle and disturb the peace. Once incorporated into the territory of the United States, all this is done away.

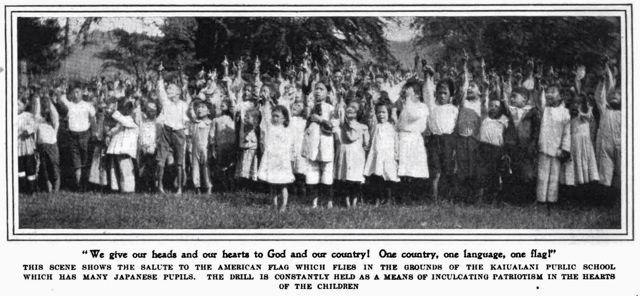

CHARACTER OF THE POPULATION.

While the character of the comparatively small population of the Hawaiian Commonwealth is a minor consideration as compared with the transcendent importance of the possession of that strategic point in the Pacific, it may be briefly considered. It is a mixed population, 24,407 Japanese and 21,616 Chinese, or together nearly one-half of the entire 109,020 on the island; but after annexation the Asiatic element would be reduced. The contract system would be terminated, and United States restriction laws as to immigration would be applied. The Hawaiian penal code (paragraph 1571) would gradually send back the Chinese laborers. This annexation joint resolution forbids further Chinese immigration, and under it those now in Hawaii can not come to other parts of the United States. Our recent treaty with Japan, to go into effect next year enables the United States to regulate the immigration of Japanese laborers. The supply being cut off, the number of Asiatics remaining in Hawaii would be very rapidly reduced by natural causes, which are plainly shown by the movements of the Asiatic population in past years; for since 1893, though the flood of Japanese coming in has been strong, the departures each year have been half as many as the arrivals. Like the Chinese, when they have accumulated a moderate competence, the craving for home takes them back. The enormous excess of men coming shows on its face that they do not come to Hawaii to establish homes. The Hawaiian laws exclude them from homestead rights.

These constant and powerful causes operating, if annexation were carried out the Asiatic proportion of the population would rapidly diminish. There is a large element of what are called Portuguese—15,191—but of these, who are a quiet, laborious population, over 7,000 have been born there, educated in the public schools, and speak English as readily as the average American child. They are a useful, orderly people, and rapidly assimilate the American ideas and institutions which now prevail on the islands.

The British element, 2,250, the German, 1,432, and others of European origin, probably 1,000, are elements with which we are perfectly familiar in our own country, which readily sympathize and blend with our own people. They will naturally adhere and cooperate as against Asiatic influence. The native Hawaiian race is decreasing from year to year by some mysterious law which has been in operation for a century. It is reasonable to suppose that within ten years after annexation the inconsiderable population of these islands will not differ widely in character from that of many parts of the United States.

Some effort has been made to that our beet-sugar Industry would be retarded by the admission of Hawaii and the free admission of its sugar product. Raw Hawaiian sugar is now admitted free of duty under the reciprocity treaty. There is so little of it, altogether amounting to not one-tenth of our consumption, that it can not affect the general price of sugar one-tenth of a cent a pound. There are but 80,000 acres of natural sugar-cane lands In Hawaii, and they are all under cultivation, unless it be possibly some that might e irrigated by pumping water from 150 to 600 feet.

There would be one difference after annexation as to the restriction upon Hawaiian sugar. At present, under the reciprocity treaty, all unrefined Hawaiian sugar is admitted free of duty, but not refined sugar. After annexation both refined and unrefined would be admitted free and sugar-refining interests in this country may object to annexation.

It has been objected that the constitution does not confer upon Congress the power to admit “territory,” but only “States.” The same objection was raised to the acquisition of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, because there was nothing in the Constitution expressly authorizing such admission by treaty, and Jefferson himself, who made the purchase, shared the doubt. But we have made eleven such acquisitions of territory, and the courts have sustained such action in all cases. Texas was annexed by a joint resolution of Congress similar to the one proposed now. The island of Navassa, in the Caribbean Sea, and many others have been made territory of the United States under the act of August 18, 1856, authorizing American citizens to take possession of unoccupied guano islands. They are United States territory, subject to our laws. So Midway island in the Pacific, 1,000 miles beyond Hawaii, was occupied, and Congress appropriated $50,000, which was expended trying to create a naval station there. The principle is that the power to acquire territory is an incident of national sovereignty.

The acquisition of these islands does not contravene our national policy or traditions. It carries out the Monroe doctrine, which excludes European powers from interfering in the American continent and outlying islands, but does not limit the United States; and this doctrine has been long applied to these very islands by our Government. As Secretary Blaine said, in 1881—

“The situation of the Hawaiian Islands, giving them strategic control of the north Pacific, brings their possession within range of questions of purely American policy.”

The annexation of these islands does not launch us upon a new policy or depart from our time-honored traditions of caring first and foremost for the safety and prosperity of the United States.

The committee recommend the adoption of the resolutions.

Marama Davidson, member of Maori women’s political advocacy group Te Whare Pora Hou states, “Protectors of Mauna a Wakea have been occupying the sacred ancestral mountain on the island of Hawai‘i for over 120 days now, to prevent the construction of this telescope. We stand in solidarity with the protectors in efforts to stop this destruction. This is a direct attack on the physical, spiritual and cultural integrity of the maunga, and the wellbeing of both the environment and people.”

Marama Davidson, member of Maori women’s political advocacy group Te Whare Pora Hou states, “Protectors of Mauna a Wakea have been occupying the sacred ancestral mountain on the island of Hawai‘i for over 120 days now, to prevent the construction of this telescope. We stand in solidarity with the protectors in efforts to stop this destruction. This is a direct attack on the physical, spiritual and cultural integrity of the maunga, and the wellbeing of both the environment and people.”

On November 20, 1892, U.S. Diplomat John Stevens assigned to Hawai‘i stated in a confidential

On November 20, 1892, U.S. Diplomat John Stevens assigned to Hawai‘i stated in a confidential

The

The

Legal Counsel was befuddled by Congress’s annexation of the Hawaiian Islands by a joint resolution. In a 1988 legal opinion, the Office of Legal Counsel addressed the

Legal Counsel was befuddled by Congress’s annexation of the Hawaiian Islands by a joint resolution. In a 1988 legal opinion, the Office of Legal Counsel addressed the  On May 4, 1898, Congressman Francis Newlands submitted a joint resolution for the annexing of the Hawaiian Islands to the U.S. House Committee on Foreign Affairs after Commodore Dewey defeated the Spanish fleet at Manila Bay, Philippines, on May 1. On May 17, the joint resolution was reported out of the committee without amendment and headed to the floor of the House of Representatives. The joint resolution’s accompanying Report justified the congressional action to seize the Hawaiian Islands as a matter of military interest. The

On May 4, 1898, Congressman Francis Newlands submitted a joint resolution for the annexing of the Hawaiian Islands to the U.S. House Committee on Foreign Affairs after Commodore Dewey defeated the Spanish fleet at Manila Bay, Philippines, on May 1. On May 17, the joint resolution was reported out of the committee without amendment and headed to the floor of the House of Representatives. The joint resolution’s accompanying Report justified the congressional action to seize the Hawaiian Islands as a matter of military interest. The

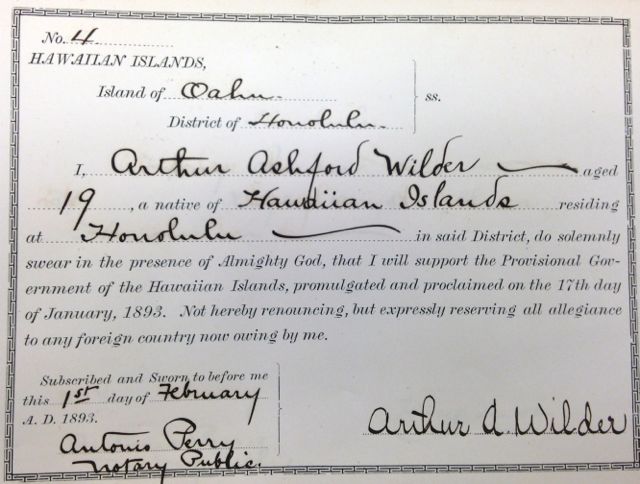

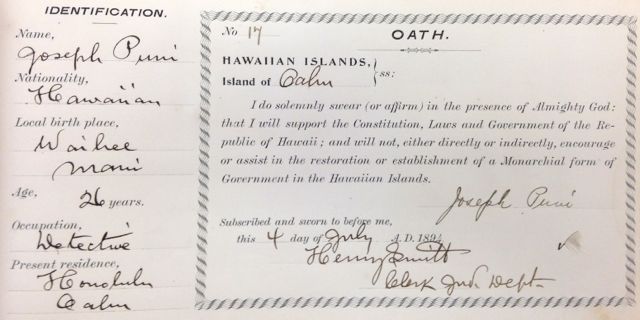

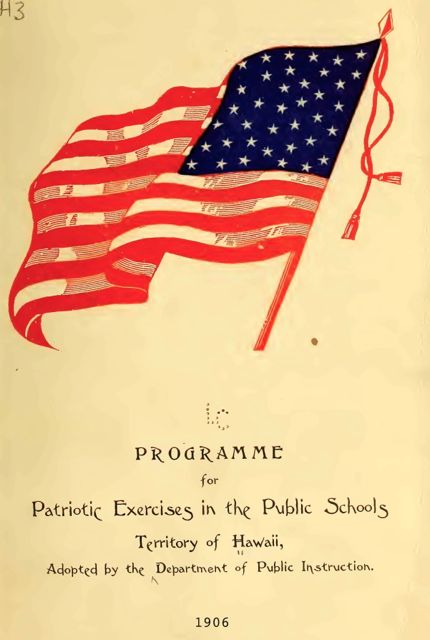

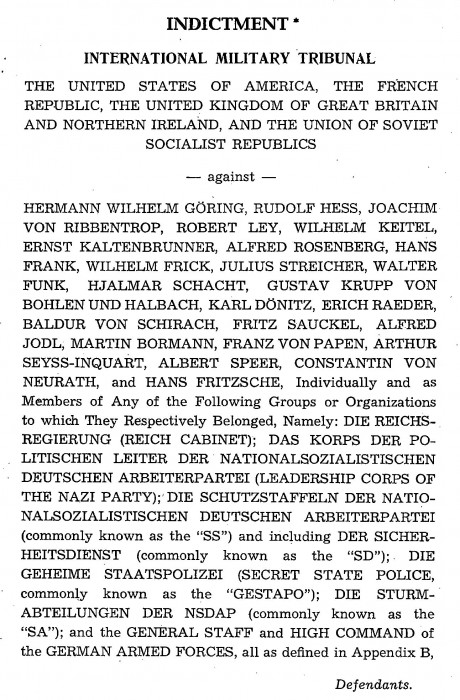

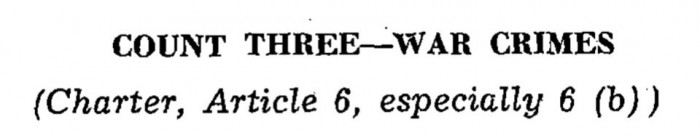

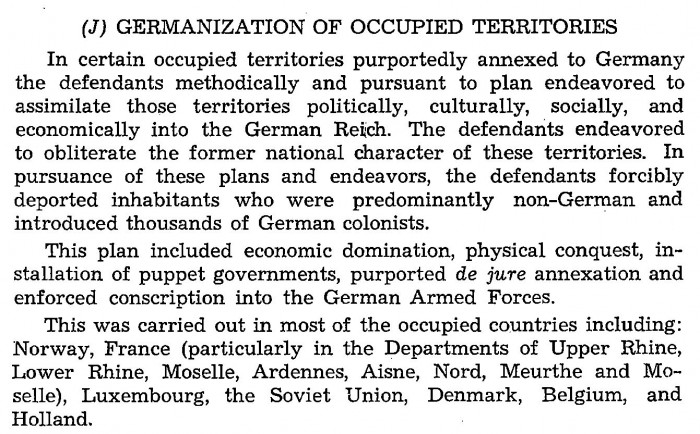

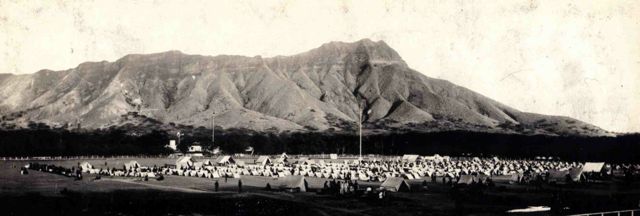

Despite objections by Senators and Representatives that foreign territory can only be acquired by treaty and not through a congressional statute, President McKinley signs the joint resolution into law on July 7, 1898, and the occupation of the Hawaiian Islands began on August 12. The war with Spain did not come to an end until April 11, 1899, after documents of ratifications of the Treaty of Paris were exchanged. Customary international law mandated the United States, as the occupying state, to establish a Military Government in order to provisionally administer the laws of the occupied state, being the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom that stood prior to the regime change on January 17, 1893. Instead of establishing a Military Government, the U.S. authorities allowed the insurgents to maintain control until the Congress could reorganize the so-called Republic of Hawai‘i.

Despite objections by Senators and Representatives that foreign territory can only be acquired by treaty and not through a congressional statute, President McKinley signs the joint resolution into law on July 7, 1898, and the occupation of the Hawaiian Islands began on August 12. The war with Spain did not come to an end until April 11, 1899, after documents of ratifications of the Treaty of Paris were exchanged. Customary international law mandated the United States, as the occupying state, to establish a Military Government in order to provisionally administer the laws of the occupied state, being the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom that stood prior to the regime change on January 17, 1893. Instead of establishing a Military Government, the U.S. authorities allowed the insurgents to maintain control until the Congress could reorganize the so-called Republic of Hawai‘i.

In 2001, the

In 2001, the