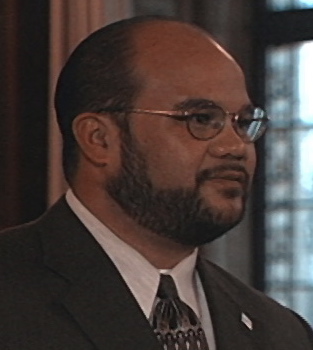

My name is Dr. David Keanu Sai and from 1999-2001, I served as Agent for the Hawaiian Kingdom in international arbitration proceedings under the auspices of the Permanent Court of Arbitration, The Hague, Netherlands. The case was Lance Paul Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom (Larsen case). I was responsible for the drafting of the pleadings as well as communication with the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s (PCA) International Bureau-Secretariat, headed by a Secretary General, regarding the case. So I am very well acquainted with the case as well as what was going on behind the formalities of the case and the confines of the published Award in the International Law Reports, vol. 119, p. 566.

My name is Dr. David Keanu Sai and from 1999-2001, I served as Agent for the Hawaiian Kingdom in international arbitration proceedings under the auspices of the Permanent Court of Arbitration, The Hague, Netherlands. The case was Lance Paul Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom (Larsen case). I was responsible for the drafting of the pleadings as well as communication with the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s (PCA) International Bureau-Secretariat, headed by a Secretary General, regarding the case. So I am very well acquainted with the case as well as what was going on behind the formalities of the case and the confines of the published Award in the International Law Reports, vol. 119, p. 566.

I am also a lecturer at the University of Hawai‘i with a M.A. and a Ph.D. in political science specializing in international relations and public law. My doctoral research and published law articles centers on the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State under a prolonged occupation by the United States of America (United States) since the Spanish-American War.

After reviewing the two Awards by the Tribunal in the South China Sea case, I perused the Philippines’ Memorial and transcripts of the proceedings to find any reference to the Larsen case that was cited in Tribunal’s Award on Jurisdiction and Admissibility (paragraph 181) as well as the Award on the Merits (paragraph 157, footnote 98). In the Memorial, which is called a pleading in international proceedings, the Philippines brought up the Larsen case in paragraphs 5.125 and 5.126. It was also mentioned by Professor Philippe Sands, QC, in his expert testimony to the Tribunal during a hearing on jurisdiction on July 8, 2015, and found on page 123 of the transcripts. On the Larsen case, the Philippine Memorial stated:

5.125 The Monetary Gold principle has also been followed once in arbitral proceedings. An arbitral tribunal applied it propio motu in Larsen v. the Hawaiian Kingdom. In that case, a resident of Hawaii sought redress from “the Hawaiian Kingdom” for its failure to protect him from the United States and the State of Hawaii. The parties, who had agreed to submit their dispute to arbitration by the PCA, hoped that the tribunal would address the question of the international legal status of Hawaii. Both parties initially argued that the Monetary Gold principle should be confined to ICJ proceedings. The tribunal rejected that argument, stating that international arbitral tribunals “operate[ ]within the general confines of public international law and, like the International Court, cannot exercise jurisdiction over a State which is not a party to its proceedings”.

5.126 The tribunal ultimately decided that it was precluded from addressing the merits because the United States, which was absent, was an indispensable party. Relying on Monetary Gold, the tribunal explained that the legal interests of the United States would form “the very subject-matter” of a decision on the merits because it could not rule on the lawfulness of the conduct of the respondent, the Kingdom of Hawaii, without necessarily evaluating the lawfulness of the conduct of the United States. It emphasized that “[t]he principle of consent in international law would be violated if this Tribunal were to make a decision at the core of which was a determination of the legality or illegality of the conduct of a non-party”.

There is much said in these two paragraphs that may escape the layman who may not be familiar with Hawai‘i’s legal history and its place in international law. By the Philippines own admission it recognized the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a party to the arbitration, and without the participation of the United States, as an indispensable third party, the Philippines stated the Larsen Tribunal “could not rule on the lawfulness of the conduct of the respondent, the Kingdom of Hawaii.”

Here at the University of Hawai‘i William S. Richardson School of Law, a few faculty members, namely Dr. Diane Desierto, Dr. David Cohen, and Carol Peterson, have gone so far as to call the Larsen case mere puffery. But can the Larsen case be an exaggeration of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s continued existence under international law and the role of the principle of indispensable third parties when it comes to the United States, as claimed by these faculty members who admitted, at a closed forum, they don’t know the legal history of Hawai‘i?

Obviously, the Philippine Government did not think so, and nor did the Tribunal in the South China Sea arbitration. As a landmark case in international arbitration, the South China Sea arbitration has drawn attention to the Larsen case again, which gives me an opportunity to set the record straight in light of the detractors, but also for those who are just curious.

In the Larsen case, the Hawaiian Kingdom, which I served as Agent along with others on my legal team, was a “Defendant,” which in international proceedings is also called a “Respondent.” This means that the Hawaiian Kingdom was defending itself from the allegations made by Larsen, as the “Plaintiff,” which is also called a “Claimant,” that the Council of Regency was allowing the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws in the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom, which led to his unfair trial and subsequent incarceration.

By going to Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom at the PCA’s case repository, it identifies me as the Agent for the Hawaiian Kingdom, identifies the Hawaiian Kingdom as a “State,” and under the heading of “case description,” it provides the dispute as follows:

“Dispute between Lance Paul Larsen (Claimant) and The Hawaiian Kingdom (Respondent) whereby

- a) Lance Paul Larsen, a Hawaiian subject, alleges that the Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom is in continual violation of its 1849 Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation with the United States of America, and in violation of the principles of international law laid [down] in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 1969, by allowing the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws over claimant’s person within the territorial jurisdiction of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

- b) Lance Paul Larsen, a Hawaiian subject, alleges that the Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom is also in continual violation of the principles of international comity by allowing the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws over the claimant’s person within the territorial jurisdiction of the Hawaiian Kingdom.”

The Philippines’ Memorial also cites an article by Bederman and Hilbert on the Larsen case that was originally published in the American Journal of International (vol. 95, p. 928), and republished the article in the Hawaiian Journal of Law and Politics (vol. 1, p. 82) that the Philippines cited. According to Bederman and Hilbert, who succinctly stated the dispute, “At the center of the PCA proceeding was…that the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist and that the Hawaiian Council of Regency (representing the Hawaiian Kingdom) is legally responsible under international law for the protection of Hawaiian subjects, including the claimant. In other words, the Hawaiian Kingdom was legally obligated to protect Larsen from the United States’ ‘unlawful imposition [over him] of [its] municipal laws’ through its political subdivision, the State of Hawaii. As a result of this responsibility, Larsen submitted, the Hawaiian Council of Regency should be liable for any international law violations that the United States committed against him.”

Clearly, the Larsen case was not about whether the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist, but was based on the presumption that it does exist, and, as such, a dispute arose between a Hawaiian national and the Hawaiian Government that stemmed from an illegal and prolonged occupation by the United States. My responsibility, as the Agent, was to defend the Hawaiian Government from Larsen’s allegation of allowing the imposition of American municipal laws in the Hawaiian Islands.

I was also keenly aware that before the PCA could establish the Arbitral Tribunal to preside over the dispute between Larsen and the Hawaiian Kingdom, it had to first confirm that the Hawaiian Kingdom as a “State” continues to exist in order for the PCA to exercise its “institutional jurisdiction” (United Nations Dispute Settlement, Permanent Court of Arbitration, p. 15) so that it could facilitate the creation of an ad hoc tribunal. By extension, the PCA also had to confirm that Larsen’s nationality was a Hawaiian subject, and the Council of Regency was the Hawaiian Government.

As an intergovernmental organization established under the 1899 Hague Convention, I, and the 1907 Hague Convention, I, the PCA facilitates the creation of ad hoc arbitral tribunals to settle disputes between two or more States, i.e., the Philippines v. China, or between a State and a private entity, i.e., Romak, S.A. v. Uzbekistan. Romak, S.A. is a Swiss company that specializes in the sale of grain and cereal products. In both cases, the States have to exist in fact and not in theory in order for the PCA to have institutional jurisdiction. Disputes must be “international” and not “municipal,” which are disputes that go before national courts of States and not international courts or tribunals.

Since the arbitration agreement between Larsen and the Hawaiian Government was submitted to the PCA on November 8, 1999, the PCA was doing their due diligence as to whether the Hawaiian Kingdom currently exists as a State under international law. If the Hawaiian Kingdom does not exist then this fact would negate the existence of the nationality of Larsen as a Hawaiian subject and the existence of the Council of Regency as the Hawaiian government, and, therefore, the dispute.

After its due diligence, however, the PCA could not deny that the Hawaiian Kingdom did exist as an independent State, and, along with other treaties, the Hawaiian Kingdom had a treaty with the Netherlands, which houses the PCA itself. However, what faced the PCA is that it could not find any evidence that the Hawaiian Kingdom had ceased to exist under international law. Only by way of a “treaty of cession,” whereby the Hawaiian Kingdom agreed to merge itself into the territory of the United States, could the Hawaiian Kingdom have been extinguished under international law.

There was never a treaty, except for American municipal laws, enacted by the United States Congress, that treat Hawai‘i as if it were annexed. Municipal laws are not international laws, as between States, but are laws that are limited in scope and authority to the territory of the State that enacted them. In other words, an American municipal law could no more annex the Hawaiian Kingdom, than it could annex the Netherlands.

My legal team and Larsen’s attorney knew this and operated on the “presumption” that the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist until evidence shows otherwise. This was the  same conclusion that the PCA came to, which prompted a telephone conversation I had with the PCA’s Secretary General, Tjaco T. van den Hout, in February 2000. In that telephone conversation, he recommended that the Hawaiian Government along with Larsen’s Counsel, Ms. Ninia Parks, provide a formal invitation to the United States Government to join in the arbitration. I recall his specific words to me on this matter. He said that in order to maintain the integrity of this case, he recommended that the Hawaiian Government, with the consent of Larsen’s legal representative, provide a formal invitation to the United States to join in the current arbitration. He then requested that I provide evidence that the invitation was made so that it can be made a part of the record for the case.

same conclusion that the PCA came to, which prompted a telephone conversation I had with the PCA’s Secretary General, Tjaco T. van den Hout, in February 2000. In that telephone conversation, he recommended that the Hawaiian Government along with Larsen’s Counsel, Ms. Ninia Parks, provide a formal invitation to the United States Government to join in the arbitration. I recall his specific words to me on this matter. He said that in order to maintain the integrity of this case, he recommended that the Hawaiian Government, with the consent of Larsen’s legal representative, provide a formal invitation to the United States to join in the current arbitration. He then requested that I provide evidence that the invitation was made so that it can be made a part of the record for the case.

This invitation would elicit one of the three possible responses: first, the United States accepts the invitation, which recognizes the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom and its government and will have to answer to its unlawful imposition of American municipal laws that led to Larsen’s unfair trial and incarceration; second, the United States denies the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom because Hawai‘i is the so-called 50th State of the Federal Union and demands that the PCA cease and desist in entertaining the dispute; or, third, the United States denies the invitation to join in the arbitration but does not deny the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the dispute between a Hawaiian national and the government representing the Hawaiian Kingdom.

On March 3, 2000, a conference call meeting was held with John Crook from the United States State Department in Washington, D.C., together with myself representing the Hawaiian Government and Ms. Parks representing Larsen. After the meeting, I drafted a letter to Crook that covered what was discussed in the meeting regarding the invitation and a carbon copy was sent to Secretary General van den Hout, as he requested, so that it could be placed on the record that an invitation was made. A few days later the United States Embassy in The Hague notified the PCA that they denied the invitation to join in the  arbitration, but requested permission from the Hawaiian Government and Ms. Parks, on behalf of Larsen, to have access to all pleadings and transcripts of the case. Both Ms. Parks and I were individually contacted by telephone from the PCA’s Deputy Secretary General, Phyllis Hamilton, of the request made by the US Embassy, which we both consented to. It was also agreed that the records of the proceedings would be open to the public.

arbitration, but requested permission from the Hawaiian Government and Ms. Parks, on behalf of Larsen, to have access to all pleadings and transcripts of the case. Both Ms. Parks and I were individually contacted by telephone from the PCA’s Deputy Secretary General, Phyllis Hamilton, of the request made by the US Embassy, which we both consented to. It was also agreed that the records of the proceedings would be open to the public.

The United States took the third option and did not deny the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Thereafter, the PCA began to form the Arbitral Tribunal the following month in April of 2000. Memorials were filed with the Tribunal by Larsen on May 22, 2000, and the Hawaiian Government on May 25, 2000. The Hawaiian Government then filed its Counter-Memorial on June 22, 2000, and Larsen its Counter-Memorial on June 23, 2000.

After the pleadings were submitted, the Tribunal issued Procedural Order no. 3 on July 17, 2000. In the Procedural Order, the Tribunal articulated the dispute from the pleadings in the following statement.

“As further defined in the pleadings of the parties, especially the Counter-Memorials, the plaintiff has requested the Tribunal to adjudge and declare (1) that his rights as a Hawaiian subject are being violated under international law as a result of the prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Islands by the United States of America”, and (2) that the plaintiff “does have redress against the Respondent Government” in relation to these violations (Plaintiff’s Counter-Memorial, para. 3). The defendant “agrees that it was the actions of the United States that violated Claimant’s rights, however denies that it failed to intervene” (Defendant’s Counter-Memorial, para. 2). Accordingly the parties agree on the first of the two issues identified by the Claimant as in dispute, but disagree on the second. The second issue only arises once it is established, or validly agreed, that the first issue is to be decided in the affirmative.”

The Tribunal further stated in the Procedural Order that it “is concerned whether the first issue does in fact raise a dispute between the parties, or, rather, a dispute between each of the parties and the United States over the treatment of the plaintiff by the United States. If it is the latter, that would appear to be a dispute which the Tribunal cannot determine, inter alia because the United States is not a party to the agreement to arbitrate.” The Tribunal, therefore, stated that it could not get to the merits of the case regarding “redress against the Respondent Government” as the second issue, until it address the first issue that Larsen’s “rights as a Hawaiian subject are being violated…by the United States of America.” This first issue that the Tribunal was asked to determine is what caused the Tribunal to raise the principle of an “indispensable third party” that stemmed from the Monetary Gold case. In other words, could the Tribunal proceed to rule on the lawfulness of the conduct of the Hawaiian Government when its judgment would imply an evaluation of the lawfulness of the conduct of the United States, which is not a party to the case.

The Tribunal scheduled oral hearings to be held at the PCA on December 7, 8 and 11, 2000.

https://vimeo.com/17007826

A day before the oral hearings were to begin on December 7, the three arbitrators met with myself and legal team and Ms. Parks in the PCA to go over the schedule and what we can expect. What they also provided to us were booklets of the decisions by the International Court of Justice, namely the Monetary Gold Removed from Rome in 1943 (Italy v. the United Kingdom, France and the United States), Case Concerning Certain Phosphate Land in Nauru (Nauru v. Australia), and Case Concerning East Timor (Portugal v. Australia).

All three cases centered on the indispensable third party principle and that we should be prepared to respond as to how this case can proceed without the participation of the United States. In the Monetary Gold case it was on the non-participation of Albania; the Nauru Case was the non-participation of New Zealand and the United Kingdom; and the East Timor case was the non-participation of Indonesia. Of the three cases, only the Nauru case could proceed because the ICJ concluded that New Zealand and the United Kingdom were not indispensable third parties.

After two days of hearings, it was evident that the Tribunal would not be able to adjudge and declare, according to Procedural Order no. 3, that Larsen’s “rights as a Hawaiian subject are being violated…by the United States of America,” because the United States was not a party to the proceedings. Without a decision by the Tribunal that finds Larsen’s rights are being violated, he would be unable to get to the second issue of having the Tribunal declare and adjudge that he “does have ‘redress against the Respondent Government’ in relation to these violations.” In light of this, I knew that Larsen would not prevail in these proceedings without the participation of the United States. On the final day of the hearings, December 11, I decided to ask the Tribunal to make a determination on a topic that I felt would not violate the indispensable third party principle that was at the center of these proceedings.

The Hawaiian Government needed a pronouncement by the Tribunal as to the legal status of the Hawaiian Kingdom under international law that would deny the lawfulness of American municipal laws within Hawaiian territory. In other words, the Hawaiian Government needed a pronouncement of international law that could be cited as a bar to American municipal laws from being applied in Hawaiian territory. This fundamental bar of one State’s municipal laws to be applied within the territory of another State centers on the legal meaning of “independence.”

In international arbitration between the Netherlands and the United States at the PCA (Island of Palmas case), the arbitrator explained what the term independence means in  international law. In the Award (p. 8), Judge Max Huber stated, “Sovereignty in the relations between States signifies independence. Independence in regard to a portion of the globe is the right to exercise therein, to the exclusion of any other State, the functions of a State. The development of the national organization of State during the last few centuries and, as a corollary, the development of international law, have established this principle of the exclusive competence of the State in regard to its own territory.”

international law. In the Award (p. 8), Judge Max Huber stated, “Sovereignty in the relations between States signifies independence. Independence in regard to a portion of the globe is the right to exercise therein, to the exclusion of any other State, the functions of a State. The development of the national organization of State during the last few centuries and, as a corollary, the development of international law, have established this principle of the exclusive competence of the State in regard to its own territory.”

Oppenheim, International Law, Vol. 1, p. 177-8 (2nd ed. 1912), explains: “Sovereignty as supreme authority, which is independent of any other earthly authority, may be said to have different aspects. As excluding dependence from any other authority, and in especial from the authority of the another State, sovereignty is independence. It is external independence with regard to the liberty of action outside its borders in the intercourse with other States which a State enjoys. It is internal independence with regard to the liberty of action of a State inside its borders. As comprising the power of a State to exercise supreme authority over all persons and things within its territory, sovereignty is territorial supremacy. As comprising the power of a State to exercise supreme authority over its citizens at home and abroad, sovereignty is personal supremacy. For these reasons a State as an International Person possesses independence and territorial and personal supremacy.”

With this in mind, I made the following statement and request to the Tribunal that is provided in the transcripts of the final day of the hearings on December 11.

“Really what needs to be addressed is what came before the occupation, whether the statehood or whether the legality or illegality of the Hawaiian Kingdom, not the illegality or legality of the United States as an occupier, but rather the Hawaiian Kingdom, has it met those particulars of international law that would warrant its continued existence, irrespective of any action taken by a third party upon that sovereignty. I believe that the principle of international law is really the equality of states and that, as the equality of states comes into being, I believe that the United States cannot be construed to have an equal right within another state’s territory, but rather they are equal within their own territorial jurisdictions which affords the international relations that come either through trade agreements or actually war – but at least the war is somehow regulated.”

The issue before the Tribunal was whether Larsen could hold to account the Hawaiian Government for allowing the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws within Hawaiian territory that led to his unfair trial and subsequent incarceration. My request of the Tribunal on the last day of the oral hearings was to have the Tribunal acknowledge and pronounce the legal status of Hawai‘i under international law as an “independent State,” which, as a co-equal, the United States could not impose its municipal laws within Hawaiian territory without violating international law.

My intent, was to move beyond the dispute with Larsen and address the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws across the entire territory of Hawai‘i and everyone affected by it, not just Larsen. I understood that my request of the Tribunal would not violate the indispensable third party principle, because for the Tribunal to make this pronouncement there would be no need to address the lawfulness or unlawfulness of the conduct of the United States, but merely to acknowledge historical facts.

My request of the Tribunal was similar to the Philippines request of the South China Sea Tribunal to determine whether or not the landmasses in the South China Sea are islands or rocks. The Philippines argued that since it is merely a determination of facts, the Tribunal would not be getting into the lawfulness or unlawfulness of the conduct of States regarding the sovereignty over these islands. The sovereign claims over these land masses would be whether the land masses are islands as defined under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea that establish a maritime zone, or are they rocks that would not establish the maritime zones. According to Article 121(3) of the Convention, an island must “sustain human habitation or economic life of [its] own” in order to generate maritime zones, i.e., the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of 200 miles from its coast. This is how the Philippines successfully argued why the principle of indispensable third parties would not apply.

On February 5, 2001, the Tribunal issued the Award on Jurisdiction, and concluded that the United States was an indispensable third party. In paragraph 12.5, the Tribunal explained, “It follows that the Tribunal cannot determine whether the [Hawaiian Kingdom] has failed to discharge its obligation towards [Lance Larsen] without ruling on the legality of the acts of the United States of America. Yet that is precisely what the Monetary Gold principle precludes the Tribunal from doing. As the International Court of Justice explained in the East Timor case, ‘the Court could not rule on the lawfulness of the conduct of a State when its judgment would imply an evaluation of the lawfulness of the conduct of another State which is not a party to the case.’”

The Tribunal, however, did answer my request, which is provided in paragraph 7.4 of the Award. The Tribunal stated, “A perusal of the material discloses that in the nineteenth century the Hawaiian Kingdom existed as an independent State recognised as such by the United States of America, the United Kingdom and various other States, including by exchanges of diplomatic or consular representatives and the conclusion of treaties.” By using the phrase, “a perusal of the material,” the Tribunal made it clear that its conclusion that the United States recognized the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State was drawn from the facts of the case.

By declaring that the United States recognized “the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State,” is another way of stating that the United States recognized that only Hawaiian laws could be applied in Hawaiian territory and not the municipal laws of the United States. Through these international proceedings, the Hawaiian Government was able to broaden the impact of an unlawful occupation beyond the Larsen case to now include all persons that have been victimized by the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws within the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

The Award of the South China Sea arbitration’s reference of the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom is recognition of the integrity of the Larsen case itself and why it is now a precedent case regarding the principle of indispensable third parties along with the Monetary Gold case and the East Timor case. It is also an acknowledgment of the caliber of those individuals who served as arbitrators, two of which are now serving as Judges on the International Court of Justice, namely Judge Christopher Greenwood and Judge James Crawford, who served as President of the Tribunal.

When I entered the University of Hawai‘i Political Science Department to get my M.A. and Ph.D. I also planned to address the misinformation regarding Hawai‘i as the 50th State of the American Union and the categorization of native Hawaiians as indigenous people as defined under United Nations documents. This is a false narrative that has already been rebuked by the mere fact of the Larsen case, which has now become a precedent case in international law. This information about the Hawaiian Kingdom has made people very uncomfortable, but that’s what happens when you’re faced with the truth.

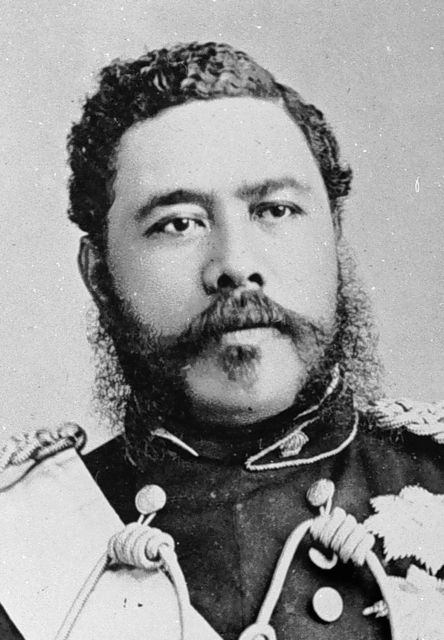

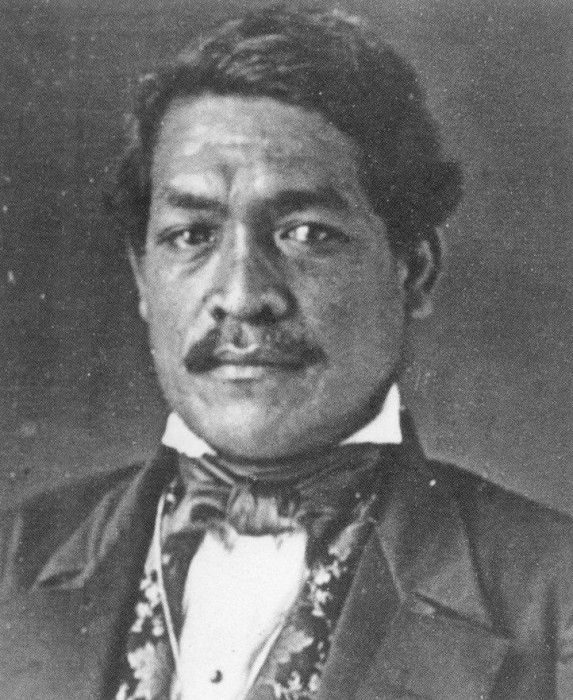

In the summer of 1842, Kamehameha III moved forward to secure the position of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a recognized independent state under international law. He sought the formal recognition of Hawaiian independence from the three naval powers of the world at the time—Great Britain, France, and the United States. To accomplish this, Kamehameha III commissioned three envoys, Timoteo Ha‘alilio, William Richards, who at the time was still an American Citizen, and Sir George Simpson, a British subject. Of all three powers, it was the British that had a legal claim over the Hawaiian Islands through cession by Kamehameha I, but for political reasons the British could not openly exert its claim over the other two naval powers. Due to the islands prime economic and strategic location in the middle of the north Pacific, the political interest of all three powers was to ensure that none would have a greater interest than the other. This caused Kamehameha III “considerable embarrassment in managing his foreign relations, and…awakened the very strong desire that his Kingdom shall be formally acknowledged by the civilized nations of the world as a sovereign and independent State.”

In the summer of 1842, Kamehameha III moved forward to secure the position of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a recognized independent state under international law. He sought the formal recognition of Hawaiian independence from the three naval powers of the world at the time—Great Britain, France, and the United States. To accomplish this, Kamehameha III commissioned three envoys, Timoteo Ha‘alilio, William Richards, who at the time was still an American Citizen, and Sir George Simpson, a British subject. Of all three powers, it was the British that had a legal claim over the Hawaiian Islands through cession by Kamehameha I, but for political reasons the British could not openly exert its claim over the other two naval powers. Due to the islands prime economic and strategic location in the middle of the north Pacific, the political interest of all three powers was to ensure that none would have a greater interest than the other. This caused Kamehameha III “considerable embarrassment in managing his foreign relations, and…awakened the very strong desire that his Kingdom shall be formally acknowledged by the civilized nations of the world as a sovereign and independent State.” While the envoys were on their diplomatic mission, a British Naval ship, HBMS Carysfort, under the command of Lord Paulet, entered Honolulu harbor on February 10, 1843, making outrageous demands on the Hawaiian government. Basing his actions on complaints made to him in letters from the British Consul, Richard Charlton, who was absent from the kingdom at the time, Paulet eventually seized control of the Hawaiian government on February 25, 1843, after threatening to level Honolulu with cannon fire. Kamehameha III was forced to surrender the kingdom, but did so under written protest and pending the outcome of the mission of his diplomats in Europe. News

While the envoys were on their diplomatic mission, a British Naval ship, HBMS Carysfort, under the command of Lord Paulet, entered Honolulu harbor on February 10, 1843, making outrageous demands on the Hawaiian government. Basing his actions on complaints made to him in letters from the British Consul, Richard Charlton, who was absent from the kingdom at the time, Paulet eventually seized control of the Hawaiian government on February 25, 1843, after threatening to level Honolulu with cannon fire. Kamehameha III was forced to surrender the kingdom, but did so under written protest and pending the outcome of the mission of his diplomats in Europe. News  of Paulet’s action reached Admiral Richard Thomas of the British Admiralty, and he sailed from the Chilean port of Valparaiso and arrived in the islands on July 25, 1843. After a meeting with Kamehameha III, Admiral Thomas determined that Charlton’s complaints did not warrant a British takeover and ordered the restoration of the Hawaiian government, which took place in a grand ceremony on July 31, 1843. At a thanksgiving service after the ceremony, Kamehameha III proclaimed before a large crowd, ua mau ke ea o ka ‘aina i ka pono (the life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness). The King’s statement became the national motto.

of Paulet’s action reached Admiral Richard Thomas of the British Admiralty, and he sailed from the Chilean port of Valparaiso and arrived in the islands on July 25, 1843. After a meeting with Kamehameha III, Admiral Thomas determined that Charlton’s complaints did not warrant a British takeover and ordered the restoration of the Hawaiian government, which took place in a grand ceremony on July 31, 1843. At a thanksgiving service after the ceremony, Kamehameha III proclaimed before a large crowd, ua mau ke ea o ka ‘aina i ka pono (the life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness). The King’s statement became the national motto.

My name is Dr. David Keanu Sai and from 1999-2001, I served as Agent for the Hawaiian Kingdom in international arbitration proceedings under the auspices of the

My name is Dr. David Keanu Sai and from 1999-2001, I served as Agent for the Hawaiian Kingdom in international arbitration proceedings under the auspices of the

arbitration, but requested permission from the Hawaiian Government and Ms. Parks, on behalf of Larsen, to have access to all pleadings and transcripts of the case. Both Ms. Parks and I were individually contacted by telephone from the PCA’s Deputy Secretary General, Phyllis Hamilton, of the request made by the US Embassy, which we both consented to. It was also agreed that the records of the proceedings would be open to the public.

arbitration, but requested permission from the Hawaiian Government and Ms. Parks, on behalf of Larsen, to have access to all pleadings and transcripts of the case. Both Ms. Parks and I were individually contacted by telephone from the PCA’s Deputy Secretary General, Phyllis Hamilton, of the request made by the US Embassy, which we both consented to. It was also agreed that the records of the proceedings would be open to the public.

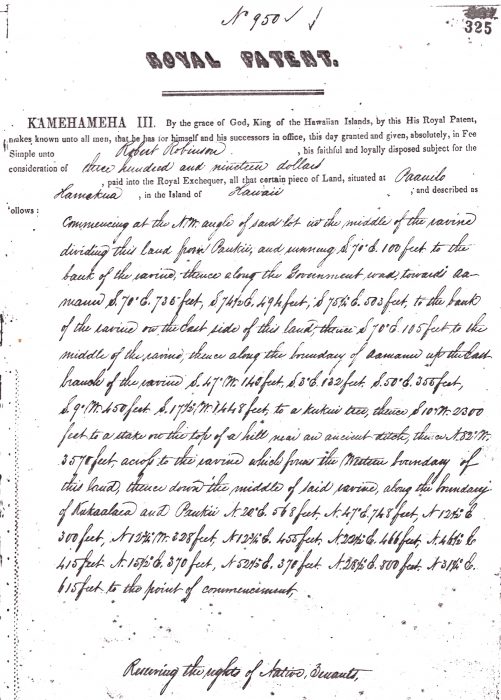

In 1839, King Kamehameha III proclaimed, by Declaration, the protection for both person and property in the kingdom by stating, “Protection is hereby secured to the persons of all the people; together with their lands, their building lots, and all their property, while they conform to the laws of the kingdom, and nothing whatever shall be taken from any individual except by express provision of the laws.” The Hawaiian Legislature, by resolution passed on October 26, 1846, acknowledged that the 1839 Declaration of Rights recognized “three classes of persons having vested rights in the lands,—1st, the government, 2nd, the landlord [Chiefs and Konohikis], and 3d, the tenant [natives] (Principles adopted by the Board of Commissioners to Quiet Land Titles, in their Adjudication of Claims Presented to Them, Resolution of the Legislative Council, Oct. 26, 1846).” Furthermore, the Legislature also recognized that the Declaration of 1839 “particularly recognizes [these] three classes of persons as having rights in the sale,” or revenue derived from the land as well.

In 1839, King Kamehameha III proclaimed, by Declaration, the protection for both person and property in the kingdom by stating, “Protection is hereby secured to the persons of all the people; together with their lands, their building lots, and all their property, while they conform to the laws of the kingdom, and nothing whatever shall be taken from any individual except by express provision of the laws.” The Hawaiian Legislature, by resolution passed on October 26, 1846, acknowledged that the 1839 Declaration of Rights recognized “three classes of persons having vested rights in the lands,—1st, the government, 2nd, the landlord [Chiefs and Konohikis], and 3d, the tenant [natives] (Principles adopted by the Board of Commissioners to Quiet Land Titles, in their Adjudication of Claims Presented to Them, Resolution of the Legislative Council, Oct. 26, 1846).” Furthermore, the Legislature also recognized that the Declaration of 1839 “particularly recognizes [these] three classes of persons as having rights in the sale,” or revenue derived from the land as well. By definition, a

By definition, a

Senator Augustus Bacon, stated, “The proposition which I propose to discuss is that a measure which provides for the annexation of foreign territory is necessarily, essentially, the subject matter of a treaty, and that the assumption of the House of Representatives in the passage of the bill and the proposition on the part of the Foreign Relations Committee that the Senate shall pass the bill, is utterly without warrant in the Constitution [31 Cong. Rec. 6145 (June 20, 1898)].”

Senator Augustus Bacon, stated, “The proposition which I propose to discuss is that a measure which provides for the annexation of foreign territory is necessarily, essentially, the subject matter of a treaty, and that the assumption of the House of Representatives in the passage of the bill and the proposition on the part of the Foreign Relations Committee that the Senate shall pass the bill, is utterly without warrant in the Constitution [31 Cong. Rec. 6145 (June 20, 1898)].” Senator William Allen stated, “A Joint Resolution if passed becomes a statute law. It has no other or greater force. It is the same as if it would be if it were entitled ‘an act’ instead of ‘A Joint Resolution.’ That is its legal classification. It is therefore impossible for the Government of the United States to reach across its boundary into the dominion of another government and annex that government or persons or property therein. But the United States may do so under the treaty making power [31 Cong. Rec. 6636 (July 4, 1898)].”

Senator William Allen stated, “A Joint Resolution if passed becomes a statute law. It has no other or greater force. It is the same as if it would be if it were entitled ‘an act’ instead of ‘A Joint Resolution.’ That is its legal classification. It is therefore impossible for the Government of the United States to reach across its boundary into the dominion of another government and annex that government or persons or property therein. But the United States may do so under the treaty making power [31 Cong. Rec. 6636 (July 4, 1898)].” Senator Thomas Turley stated, “The Joint Resolution itself, it is admitted, amounts to nothing so far as carrying any effective force is concerned. It does not bring that country within our boundaries. It does not consummate itself [31 Cong. Rec. 6339 (June 25, 1898)].”

Senator Thomas Turley stated, “The Joint Resolution itself, it is admitted, amounts to nothing so far as carrying any effective force is concerned. It does not bring that country within our boundaries. It does not consummate itself [31 Cong. Rec. 6339 (June 25, 1898)].” speak to me of a ‘treaty’ when we are confronted with a mere proposition negotiated between the plenipotentiaries of two

speak to me of a ‘treaty’ when we are confronted with a mere proposition negotiated between the plenipotentiaries of two The Hawaiian government selected Professor

The Hawaiian government selected Professor

Ms. Ninia Parks, counsel for Lance Larsen, selected

Ms. Ninia Parks, counsel for Lance Larsen, selected  Once Mr. Agard was able to confirm the selections with the PCA, these two arbitrators would recommend a person to be the president of the tribunal. Both Greenwood and Griffith nominated Professor

Once Mr. Agard was able to confirm the selections with the PCA, these two arbitrators would recommend a person to be the president of the tribunal. Both Greenwood and Griffith nominated Professor