https://vimeo.com/107290353

Category Archives: War Crimes

ABC Radio Australia: Could the U.S. be Guilty of Committing War Crimes in Hawai‘i?

To hear the ABC news radio coverage click here.

ABC News Australia Covers War Crimes Reported to U.S. Attorney General

To go to ABC News Australia coverage click here.

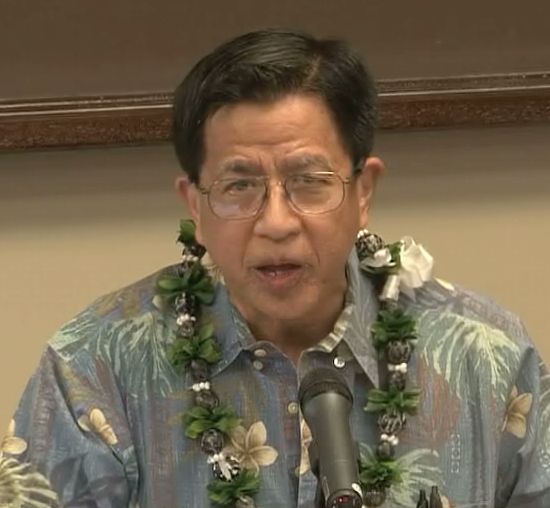

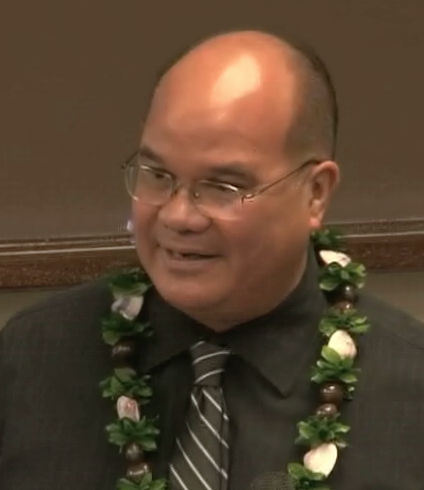

State of Hawai‘i Hawaiian Homes Commissioner “Uncle Joe” Tassil Calls for Moratorium on all Evictions in Hawaiian Homes because of War Crimes

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE:

HAWAIIAN HOMES COMMISSIONER “UNCLE JOE” TASSIL CALLS FOR MORATORIUM ON ALL EVICTIONS IN HAWAIIAN HOMES

9/22/2014

At Hawaiian Homes hearing at Paukukalo 10:00 a.m. this morning, “Uncle Joe” Tassil called for a moratorium of all evictions in Hawaiian Homes until the Justice Department responds to a letter authored by Dr. Chang, Professor of Law at UH which letter was premised upon a letter and memorandum drafted by Dr. Keanu Sai, Ph.D. regarding the current existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the unlawful occupation by the United States in Hawai’i. Attorney Dexter Kaiama testified on behalf of qualified Hawaiian Beneficiaries as to Department of Hawaiian Homelands, a state agency’s, lack of jurisdiction. Christopher Fishkin, a legal assistant to a law office in Wailuku, testified separately, to numerous violations of Federal law by DHHL and violations of the rights of qualified Hawaiian beneficiaries pursuant to the Federal law. Fishkin also encouraged the Commissioners to adopt Commissioner Tassil’s recommendation of a moratorium of evictions, to review and address the violations of Hawaiians’ rights in Hawaiian Homes which Fishkin asserted were being perpetuated against qualified Hawaiian beneficiaries under the color of state law.

At Hawaiian Homes hearing at Paukukalo 10:00 a.m. this morning, “Uncle Joe” Tassil called for a moratorium of all evictions in Hawaiian Homes until the Justice Department responds to a letter authored by Dr. Chang, Professor of Law at UH which letter was premised upon a letter and memorandum drafted by Dr. Keanu Sai, Ph.D. regarding the current existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the unlawful occupation by the United States in Hawai’i. Attorney Dexter Kaiama testified on behalf of qualified Hawaiian Beneficiaries as to Department of Hawaiian Homelands, a state agency’s, lack of jurisdiction. Christopher Fishkin, a legal assistant to a law office in Wailuku, testified separately, to numerous violations of Federal law by DHHL and violations of the rights of qualified Hawaiian beneficiaries pursuant to the Federal law. Fishkin also encouraged the Commissioners to adopt Commissioner Tassil’s recommendation of a moratorium of evictions, to review and address the violations of Hawaiians’ rights in Hawaiian Homes which Fishkin asserted were being perpetuated against qualified Hawaiian beneficiaries under the color of state law.

Representative of Habitat for Humanity and solar energy providers to Hawaiian Homes testified as to lengthy delays in their being able to provide services to Hawaiians in Hawaiian Homes and unclear contractual obligations in order to do so.

Contact Commissioner Joe Tassil for more info. 808-664-6901

Aloha ‘Aina Talk Story with Associate Professor Kaleikoa Ka‘eo

https://vimeo.com/106904451

A very provocative talk story session with Associate Professor Kaleikoa Kaeo of the University of Hawai‘i Maui College and Keala Kelly about Hawaiian Consciousness and being Enlightened. This is part 1 of 2.

Press Conference of Professor Williamson Chang at the University of Hawai‘i Law School

Click here to download Professor Chang’s prepared statement read at the press conference.

Kingdom Media Hawai‘i Live Stream of Professor Chang’s Press Conference

Kingdom Media Hawai‘i will be providing a live stream of Professor Chang’s press conference at the University of Hawai‘i William S. Richardson School of Law. The press conference will begin at 2:00 pm in front of the Law School’s administration building across from the Law Library.

UPDATE: Due to technical difficulties the live streaming was not able to take place. Kingdom Media Hawai‘i, however, did record the press conference and will be playing it on its website.

https://vimeo.com/107008784

Senior Law Professor Reports War Crimes to U.S. Attorney General

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Press Conference at William S. Richardson School of Law, University of Hawai‘i at Manoa, Monday, September 22, 2014, at 2:00 pm

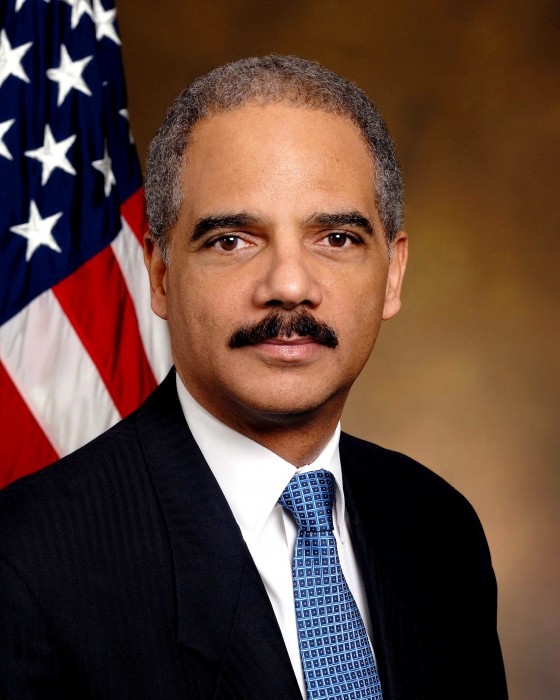

University of Hawai‘i’s senior law professor notifies U.S. Attorney General, Eric Holder, Jr., of war crimes committed in the Hawaiian Islands

HONOLULU (September 19, 2014) – Senior law professor Williamson B.C. Chang has reported to U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder, Jr. that war crimes have and continue to be committed in the Hawaiian Islands. Professor Chang is a faculty member of the University of Hawai‘i William S. Richardson School of Law and has been with the law school for the past thirty-eight years.

HONOLULU (September 19, 2014) – Senior law professor Williamson B.C. Chang has reported to U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder, Jr. that war crimes have and continue to be committed in the Hawaiian Islands. Professor Chang is a faculty member of the University of Hawai‘i William S. Richardson School of Law and has been with the law school for the past thirty-eight years.

The Office of Hawaiian Affairs’ (OHA) top executive, CEO Kamanaopono Crabbe, contracted political scientist, Dr. Keanu Sai, to draft a memorandum on the legal status of Hawai‘i under international law. Based on information Sai disclosed in what has become known as the OHA Memo, CEO Crabbe authored a letter to Secretary of State, John Kerry. Crabbe sought legal clarification on the status of Hawai‘i from Secretary Kerry primarily because Sai concluded that OHA is in possession of monies acquired from the “State of Hawai‘i’s” general fund through pillaging.

Pillaging is prohibited under article 33 of the 1949 Geneva Convention, IV, being a war crime under U.S. federal criminal law as well as a felony. According to 18 U.S.C. §2441 “Whoever, whether inside or outside the United States, commits a war crime…shall be fined under the this title or imprisoned for life or any number of years, or both, and if death results to the victim, shall also be subject to the penalty of death.”

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia has defined pillaging, which is the same as plunder, as “the fraudulent appropriation of public and private funds belonging to…the opposing party.” According to the OHA Memo, the State of Hawai‘i is not a legitimate government under international law and as a self-declared entity it has no authority to collect taxes from individuals throughout the Hawaiian Islands. This fraudulent collection of monies is a form of pillaging from public property that belongs to the Hawaiian Kingdom, not the United States.

In the letter addressed to Attorney General Holder, Professor Chang described his reporting of war crimes as being obligated under Federal criminal law and if he did not report the war crimes he could be fined or imprisoned for three years. “Pursuant to 18 U.S.C. §4—Misprision of felony, I am legally obligated to report to you the knowledge I have about multiple felonies that prima facie have been and continue to be committed here in the Hawaiian Islands,” Chang said. “I have been made aware of these felonies through the memorandum by political scientist David Keanu Sai, Ph.D., who was contracted by the State of Hawai‘i Office of Hawaiian Affairs, entitled Memorandum for Ka Pouhana, CEO of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs regarding Hawai‘i as an Independent State and the Impacts it has on the Office of Hawaiian Affairs.”

In the letter addressed to Attorney General Holder, Professor Chang described his reporting of war crimes as being obligated under Federal criminal law and if he did not report the war crimes he could be fined or imprisoned for three years. “Pursuant to 18 U.S.C. §4—Misprision of felony, I am legally obligated to report to you the knowledge I have about multiple felonies that prima facie have been and continue to be committed here in the Hawaiian Islands,” Chang said. “I have been made aware of these felonies through the memorandum by political scientist David Keanu Sai, Ph.D., who was contracted by the State of Hawai‘i Office of Hawaiian Affairs, entitled Memorandum for Ka Pouhana, CEO of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs regarding Hawai‘i as an Independent State and the Impacts it has on the Office of Hawaiian Affairs.”

Chang explained the action taken was not only prompted by a legal obligation, but also because he’s a State of Hawai‘i employee. “I and other State officials and employees receive State monies that have been implicated as being gained through the commission of felonies, namely the war crime of pillaging, and we could also face prosecution under 18 U.S.C. §3—Accessory after the fact,” Chang said. “I am deeply concerned about this matter that affects all State of Hawai‘i officials and employees, including myself personally.”

Due to the urgency of the matter Chang’s letter asks for a response from the Department of Justice within two weeks. If the Department of Justice’s “response in two weeks is able to refute the evidence provided for in the Memo, then assuredly the felonies—war crimes—have not been committed,” Chang said. The letter goes on to say, “But if your office is not able to refute the evidence, then this is a matter for the U.S. Pacific Command, being the occupying power, and all State of Hawai‘i officials and employees, as well as I, are compelled to comply with Hawaiian Kingdom law and the law of occupation.”

Chang’s letter was also carbon copied to the Commander of the U.S. Pacific Command headquartered at Camp Smith, Island of O‘ahu, and to the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court in The Hague, Netherlands.

The press conference will be located in front of the Administration building across from the Law Library. Parking is provided in the parking structure behind the law school at $5.00.

Joining Professor Chang at Monday’s press conference will be some of the 17 State of Hawaii employees from the University of Hawaii, the Department of Human Services, the Department of Public Safety, the Maui Fire Department, and the Department of Hawaiian Homelands, who endorsed the letter. Dr. Sai will also be at the press conference.

Click here to download Professor Chang’s letter.

Click here to download the OHA Memo.

Star-Advertiser Front Page: Memo implies nation effort leads to war crimes

In today’s Honolulu Star-Advertiser newspaper, reporter Rob Perez centers his story on a 44-page memorandum authored by Dr. David Keanu Sai, political scientist, under contract by the CEO of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs (OHA), Dr. Kamana‘opono Crabbe. Perez reports, “The state Office of Hawaiian Affairs administrator paid a controversial political scientist $25,000 to write a memo that calls into question the validity of OHA’s nation-building effort, even raising the question of whether the office’s trustees are committing war crimes by pursuing it.”

In today’s Honolulu Star-Advertiser newspaper, reporter Rob Perez centers his story on a 44-page memorandum authored by Dr. David Keanu Sai, political scientist, under contract by the CEO of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs (OHA), Dr. Kamana‘opono Crabbe. Perez reports, “The state Office of Hawaiian Affairs administrator paid a controversial political scientist $25,000 to write a memo that calls into question the validity of OHA’s nation-building effort, even raising the question of whether the office’s trustees are committing war crimes by pursuing it.”

The article draws attention to the memo, but it may give the impression that Dr. Crabbe was not authorized to contract the services of Dr. Sai without OHA Trustees approval as stated by Trustee Peter Apo. Perez, however, correctly stated, if you keep reading, “Crabbe, OHA’s chief executive since January 2012, has the authority to spend up to $25,000 without getting prior board approval.” Perez reported: “It was part of a follow-up due diligence effort so I could protect trustees and OHA leadership of any risks that might be incurred,” Crabbe wrote. “I also provided Dr. Sai’s memo to trustees so they could use it in their deliberations. I believe we should consider all points of view, even controversial ones, to fully understand this complex issue.”

The article draws attention to the memo, but it may give the impression that Dr. Crabbe was not authorized to contract the services of Dr. Sai without OHA Trustees approval as stated by Trustee Peter Apo. Perez, however, correctly stated, if you keep reading, “Crabbe, OHA’s chief executive since January 2012, has the authority to spend up to $25,000 without getting prior board approval.” Perez reported: “It was part of a follow-up due diligence effort so I could protect trustees and OHA leadership of any risks that might be incurred,” Crabbe wrote. “I also provided Dr. Sai’s memo to trustees so they could use it in their deliberations. I believe we should consider all points of view, even controversial ones, to fully understand this complex issue.”

Dr. Crabbe was seeking to have the Trustees, after receiving a copy of the memo, to meet with Dr. Sai in a Board meeting to ask questions regarding the memo, but he was unsuccessful. Instead, you get uninformed opinions made by Chair Trustee Collette Machado and Apo attempting to paint the picture that there was some collusion going on between Dr. Crabbe and Dr. Sai. This was clearly not the case as Perez reported.

Perez also mentions another contract Dr. Sai has with OHA entered in 2009 for $70,000.00 to complete a book on land titles to be academically published by the University of Hawai‘i Press. Perez reported, “OHA recently agreed to an extension allowing him more time to work on the manuscript and has withheld a final payment of $5,000 until the book is published. Sai’s initial research led him in the 1990s to co-found Perfect Title Co., which cited Hawaiian kingdom law to contend that existing land titles in Hawaii were defective. Sai said his book will detail how the title problem can be fixed.” This book contract with OHA occurred before Dr. Crabbe was at OHA.

The article also mentions that Dr. Sai was convicted of a felony, attempted theft, but failed to explain what the subject of the theft was, therefore implying Dr. Sai was convicted of stealing money from clients of Perfect Title Company. The crime Dr. Sai was alleged to have committed was not the attempted theft of money, but rather the attempted theft of land by doing title reports and providing the remedy to the defect in title under Hawaiian law. When applying the larceny (theft) law it can only apply to personal property, which is moveable property, as opposed to real property (real estate), which is immovable. This distinction is clearly stated in the definition of larceny where the property has to be “carried away” or “attempted to carried away.”

According to the United States Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), larceny-theft is “the unlawful taking, carrying, leading, or riding away of property from the possession or constructive possession of another. Examples are thefts of bicycles, motor vehicle parts and accessories, shoplifting, pocket-picking, or the stealing of any property or article that is not taken by force and violence or by fraud. Attempted larcenies are included.” A home, being real property, cannot be carried away by doing a title search. Dr. Sai and two clients of Perfect Title Company are the only individuals in the world to have been convicted of attempting to steal a home through a title report, which is not theft. If there was to be any allegation of a crime, it should have been conspiracy and/or fraud. That was not the case because the title report by Perfect Title Company was irrefutable.

As egregious as it sounds, it is not only used in an attempt to disparage the reputation of Dr. Sai, but it is also a war crime by depriving Dr. Sai a fair and regular trial, especially on a manufactured charge of a crime that doesn’t legally exist. This was the subject of a federal lawsuit Dr. Sai filed in a United States District Court in Washington, D.C., Sai v. Clinton, et. al., in 2010. The Federal judge dismissed the case stating it was a political question, which is an option U.S. judges can use to say it belongs to the executive or legislative branches of government and not the judicial branch. The complaint was not dismissed because it was a frivolous claim.

In his interview with Perez, Dr. Sai brought to his attention that $25,000.00 to do a memorandum needs to be kept in context. A prior memo contracted by OHA with an attorney that centered on strategies toward federal recognition cost $75,000.00. Dr. Sai also told Perez that Norma Wong, a consultant to Kana‘iolowalu, and close confidant and advisor to former Governor John Waihe‘e, III, Chair of the Roll Commission, was paid two increments of $250,000.00 a year for a total of $500,000.00. Chair Waihe‘e also contracted Dennis Dwyer for a total of $1.3 million dollars to be Kana‘iolowalu’s federal lobbyist in Washington, D.C. Dwyer was also contracted by the Honolulu Rail Project’s HART to be its federal lobbyist and was paid $1.43 million dollars from 2007 to 2013. Dr. Sai also told Perez that Clyde Namuo, who was also the former CEO for OHA before Dr. Crabbe, was simultaneously collecting a full-time salary as Kana‘iolowalu’s Executive Director while he was also collecting a full-time salary as director for the Polynesian Voyaging Society.

We have provided a link to Dr. Sai’s memorandum in order to provide the public with access to the information that was at the center of the story. The public can now read what the Trustees have in their possession and be informed by the diligent research of a political scientist and not a politician. In the memo, Dr. Sai did not solely focus on federal recognition, but also recommended that OHA continue its services to the Native (aboriginal) Hawaiian community, under the doctrine of necessity, so long as it does not conflict with Hawaiian Kingdom law and the international laws of occupation.

Trustees Apo and Machado would be better served by focusing on the existence or non existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a country under international law first and whether or not war crimes have been committed. To render Dr. Sai’s memorandum moot, the Trustees should focus on the Department of Justice, Office of Legal Counsel, to rebut the analysis and provide evidence that the Hawaiian Kingdom was extinguished under international law, which was the subject of Dr. Crabbe’s letter to Secretary of State Kerry. If the Hawaiian Kingdom does not exist under international law and Hawai‘i is the 50th State of the American Union, then the U.S. Department of Justice should have no hesitation providing the evidence in a timely manner. The problem, however, is it hasn’t, which only reinforces the presumption of continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

This is a very serious issue and this subject should not be taken lightly.

State of Hawai‘i Judge Says He Received Summons from the International Criminal Court

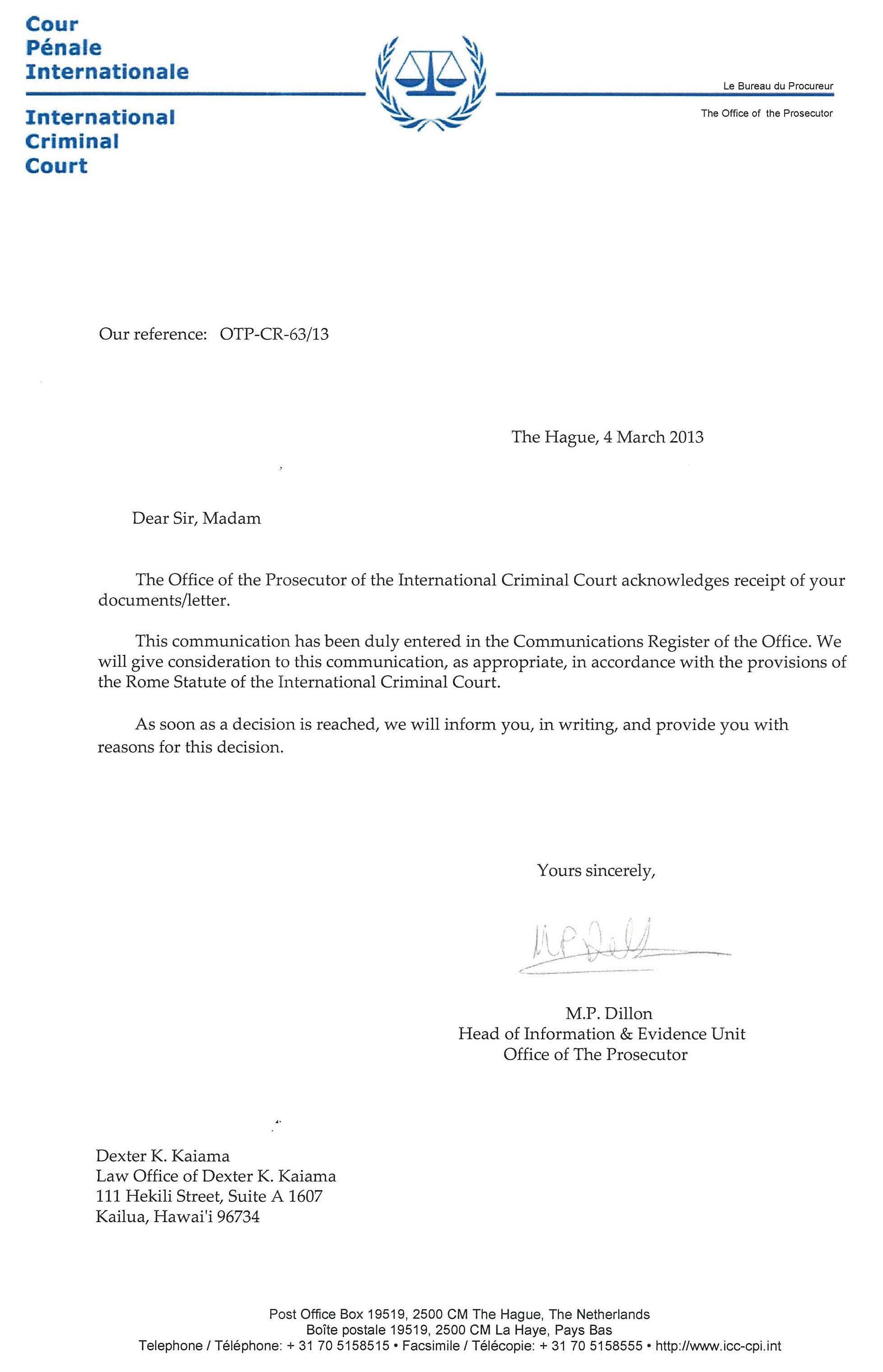

Dexter Kaiama, an attorney that represents war crime victims, was told by another attorney that Judge Harry Freitas admitted to him and the Prosecutor for Hawai‘i County in a conference call that he received a warrant from the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague, Netherlands, to appear before the Court. Freitas is a District Court Judge for the Third Circuit in the city of Hilo, Island of Hawai‘i.

Dexter Kaiama, an attorney that represents war crime victims, was told by another attorney that Judge Harry Freitas admitted to him and the Prosecutor for Hawai‘i County in a conference call that he received a warrant from the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague, Netherlands, to appear before the Court. Freitas is a District Court Judge for the Third Circuit in the city of Hilo, Island of Hawai‘i.

In February 2013, Kaiama submitted the following complaint on behalf of his client with the Prosecutor of the ICC alleging Judge Harry P. Freitas committed a war crime by willfully depriving his client of a fair and regular trial prescribed by the Fourth Geneva Convention, and that Federal National Mortgage Association, and attorneys Blue Kaanehe, Charles Prather, and Peter Keegan were complicit in these proceedings and therefore committed a war crime as accessories.

In February 2013, Kaiama submitted the following complaint on behalf of his client with the Prosecutor of the ICC alleging Judge Harry P. Freitas committed a war crime by willfully depriving his client of a fair and regular trial prescribed by the Fourth Geneva Convention, and that Federal National Mortgage Association, and attorneys Blue Kaanehe, Charles Prather, and Peter Keegan were complicit in these proceedings and therefore committed a war crime as accessories.

On March 4, 2013, the Office of the Prosecutor’s Information and Evidence Unit acknowledged receipt of the complaint and assigned it case no. OTP-CR-63/13.

The International Criminal Court’s Pre-Trial Chamber (PTC) issues both arrest warrants and summons at the request of the Prosecutor. It is unlikely that Freitas received a “warrant,” but rather a “summons” to appear before the Court. “Warrants” are orders directed to governments for the arrest and apprehension of war crime suspects to ensure appearance before the Court, while “summons” are sent to war crime suspects themselves so they could voluntarily appear before the Court.

The PTC would issue a summons if there are reasonable grounds to believe that the person has committed the alleged crimes, and that the summons is sufficient to ensure appearance before the Court on a specific day and time. Both warrants and summons can be sealed by the Court, which makes them only accessible to persons authorized by the Court. And once it can be ensured that victims and witnesses can be adequately protected, the Prosecutor could apply to the Court to unseal the warrants or summons in an effort to garner international attention and support for the arrests or summons.

It appears that the proceedings and summons are under seal because there is no mention of it on the website of the ICC. In the ICC case The Prosecutor v. Bosco Ntaganda, an arrest warrant was under seal for two years. In other cases the warrants or summons were unsealed within a month. Freitas, however, appears to have been confident enough to disclose the matter to both the attorney and the Prosecutor for the County of Hawai‘i in a conference call because he did state to both that he may be traveling to Europe soon.

When Freitas disclosed to two officers of the State of Hawai‘i court that he received a summons from the ICC it should draw international attention because if Hawai‘i was a part of the territory of the United States the ICC would not have issued the summons in the first place. The United States has not agreed to the jurisdiction of the ICC and therefore the Court would have been precluded from sending a summons if Freitas was a judge within the territory of the United States of America. The acting Government acceded to the jurisdiction of the ICC, which provided the basis for the ICC to exercise jurisdiction over the Hawaiian Islands. Hawai‘i is not a part of the United States and has been under an illegal and prolonged occupation since 1898 in direct violation of international law and the law of occupation.

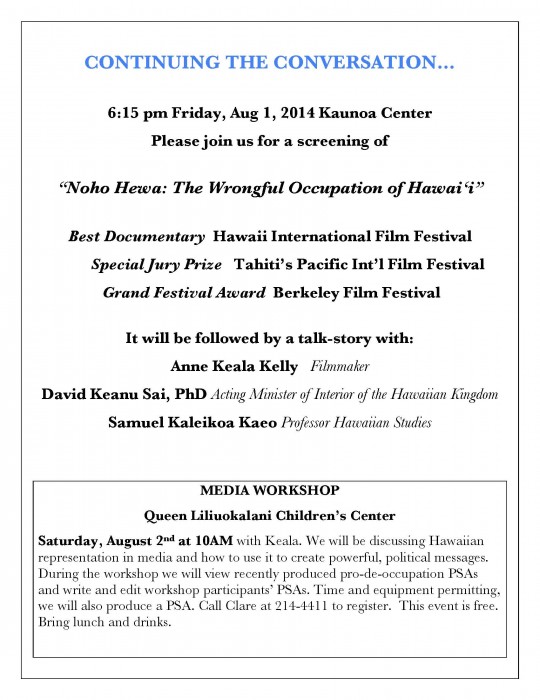

Continuing the Conversation: The Wrongful Occupation of Hawai‘i

Big Island Video News: Case Against Kale Gumapac Dismissed

HILO, Hawaii – Illegal trespassing charges against Kale Gumapac were dropped by prosecutors last week.

In an interview conducted outside the Hilo Courthouse on Friday, Gumapac and his attorney Dexter Kaiama said they had planned to go to trial that same day before hearing word that the case was dismissed without prejudice.

Gumapac made headlines last year when his refusal to pay his mortgage on his Hawaiian Paradise Park home resulted in his forceful eviction. Gumapac said he was simply following the terms of his contract, and according to he and his lawyer Dexter Kaiama, there is an inherent defect in all land title in Hawaii thanks to the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Big Island Video News covered the case in a five part series called “Defected: Testing Hawaiian Sovereignty” (video below)

While producing the series, Big Island Video News contacted Deutsche Bank, the trustee of the mortgage, who informed us the servicer of the mortgage (the entity in charge of the foreclosure activity and the post-maintenance, sale and disposition of the property) was another company called Ocwen Loan Servicing. The very same day we gleaned that information, Big Island Video News also received – apparently by coincidence – a media release from the Office of Hawaii’s Attorney General detailing a $2.1 billion joint state-federal settlement with Ocwen for servicing misconduct.

Gumapac says he was able to submit a claim and received a cash payment under the settlement. Gumapac was prepared to present the payment as evidence in his trial.

Gumapac and Kaiama were also prepared to call Dr. Keanu Sai and Professor Williamson Chang as expert witnesses. The work of both men was recently cited in a highly publicized letter to Secretary of State John Kerry written by Office of Hawaiian Affairs CEO Kamana’opono Crabbe (later rescinded by the OHA Board of Trustees) asking for clarification – among other things – on the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

By What Authority is the U.S. Department of Interior In Hawai‘i?

The U.S. Department of Interior (DOI) will be in the Hawaiian Kingdom holding public meetings throughout the Islands from June 23 to August 8, 2014 to get responses from the Native Hawaiian community to consider reestablishing a government-to-government relationship between the United States and the Native Hawaiian community. Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell who visited the country last year heads the DOI.

The U.S. Department of Interior (DOI) will be in the Hawaiian Kingdom holding public meetings throughout the Islands from June 23 to August 8, 2014 to get responses from the Native Hawaiian community to consider reestablishing a government-to-government relationship between the United States and the Native Hawaiian community. Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell who visited the country last year heads the DOI.

In a press release of June 18, 2014, the DOI stated, “The purpose of such a relationship would be to more effectively implement the special political and trust relationship that currently exists between the Federal government and the Native Hawaiian community. Today’s action, known as an Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPRM), provides for an extensive series of public meetings and consultations in Hawaii and Indian Country to solicit comments that could help determine whether the Department develops a formal, administrative procedure for reestablishing an official government-to-government relationship with the Native Hawaiian community and if so, what that procedure should be.”

“When I met with members of the Native Hawaiian community last year during my visit to the state, I learned first-hand about Hawaii’s unique history and the importance of the special trust relationship that exists between the Federal government and the Native Hawaiian community,” said Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell. “Through this step, the Department is responding to requests from not only the Native Hawaiian community but also state and local leaders and interested parties who recognize that we need to begin a conversation of diverse voices to help determine the best path forward for honoring the trust relationship that Congress has created specifically to benefit Native Hawaiians.”

At the center of the public meetings are five “threshold questions” for the community to respond to:

- Should the Secretary propose an administrative rule that would facilitate the reestablishment of a government-to-government relationship with the Native Hawaiian community?

- Should the Secretary assist the Native Hawaiian community in reorganizing its government, with which the United States could reestablish a government-to-government relationship?

- If so, what process should be established for drafting and ratifying a reorganized Native Hawaiian government’s constitution or other governing document?

- Should the Secretary instead rely on the reorganization of a Native Hawaiian government through a process established by the Native Hawaiian community and facilitated by the State of Hawaii, to the extent such a process is consistent with Federal law?

- If so, what conditions should the Secretary establish as prerequisites to Federal acknowledgment of a government-to-government relationship with the reorganized Native Hawaiian government?

The DOI stated, “Over many decades, Congress has enacted more than 150 statutes that specifically recognize and implement this trust relationship with the Native Hawaiian community, including the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act, the Native Hawaiian Education Act, and the Native Hawaiian Health Care Act. The Native Hawaiian community, however, has not had a formal governing entity since the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii in 1893. In 1993, Congress enacted the Apology Resolution which offered an apology to Native Hawaiians on behalf of the United States for its role in the overthrow and committed the U.S. government to a process of reconciliation. In 2000, the Department of the Interior and the Department of Justice jointly issued a report on the reconciliation process that identified self-determination for Native Hawaiians under Federal law as their leading recommendation.”

A careful review of the joint report by the DOI and the Department of Justice, the report acknowledges that the Hawaiian Kingdom was a recognized sovereign and independent State. “The United States clearly viewed the Kingdom of Hawai‘i as an independent nation as evidenced by the negotiation and signing of several treaties (p. 22).” The report also acknowledges President Cleveland’s withdrawal of the first treaty of annexation entered into with the so-called provisional government and President Harrison’s administration; the subsequent investigation, which concluded the provisional government was self-proclaimed and that the United States was responsible for the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian government; and the executive agreement between the Queen and the President whereby the U.S. would restore the government and the Queen to grant amnesty. “President Cleveland did not desire, nor did he have the support of Congress, to engage United States military forces to declare war against the American citizens who controlled the Provisional Government (p. 28).” This was an act of non-compliance to the agreement of restoration, which allowed the insurgents to maintain unlawful control.

The report also acknowledges the failure of the second treaty of annexation entered into between the insurgency, calling themselves the Republic of Hawai‘i, and President McKinley, which resulted in Congress passing a joint resolution instead. The reported stated:

“With the election of President McKinley in 1896, the pro-annexation forces gained strength. The Republic of Hawai‘i continued to push for annexation although many Native Hawaiians were opposed. In September 1897, the “Petition against the Annexation of Hawaii Submitted to the U.S. Senate in 1897 by the Hawaiian Patriotic League of the Hawaiian Islands”, expressed the views of Native Hawaiians. The petition, signed by 21,169 people (more than half of the Native Hawaiian population) from Kaua‘i, Maui, Hawai‘i, Moloka‘i, O‘ahu, Lana‘i, and Kaho‘olawe provides evidence that Native Hawaiians were against annexation and wanted independence under a Monarchy (p. 29).”

…

“Consistent with the wishes expressed by Native Hawaiians, the Treaty of Annexation failed to pass the United States Senate by a two-thirds majority vote. However, by 1898, with the outbreak of the Spanish-American War in both the Pacific and Caribbean, the Newlands Joint Resolution of Annexation (Annexation Resolution) was offered by the pro-annexation forces and passed by a simple majority of the United States Senate and House of Representatives, thus becoming the instrument used to effect the annexation of the Republic of Hawai‘i. The constitutionality of the use of a Joint Resolution in lieu of a Treaty to annex Hawai‘i was a contentious issue at the time (p. 30).”

From this point the report continues a narrative of historical events to the present day that “assumes” the joint resolution of annexation extinguished the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent and sovereign State. To support this erroneous position, the report restates a section of the 1993 Apology resolution, “Whereas the Newlands [Annexation] Resolution effected the transaction between the Republic of Hawai‘i and the United States Government (p. 30).” This resolution is problematic on two points: first, as an act of Congress the resolution has no effect beyond United States territory; and, second, the Republic of Hawai‘i was not a government, but self-declared, which the Apology resolution admitted.

What the report conveniently omits is the conclusion of the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel opinion on the “Newlands [Annexation] Resolution” in its 1988 Opinion “Legal Issues Raised by Proposed Presidential Proclamation To Extend the Territorial Sea.” Douglas Kmiec, Acting Assistant Attorney General, authored the memorandum for Abraham D. Sofaer, legal advisor to the U.S. State Department. The Opinion states that the “clearest source of constitutional power to acquire territory is the treaty making power (p. 247).” When it came to Hawai‘i, however, Kmiec had a difficult time explaining how the Congress could acquire territory by a joint resolution. Kmiec referenced a U.S. constitutional scholar, Professor Willoughby, who stated:

“The constitutionality of the annexation of Hawaii, by a simple legislative act, was strenuously contested at the time both in Congress and by the press. The right to annex by treaty was not denied, but is was denied that this might be done by a simple legislative act… Only by means of treaties, it was asserted, can the relations between States be governed, for a legislative act is necessarily without extraterritorial force—confined in its operation to the territory of the State by whose legislature it is enacted (p. 252).”

After covering the limitation of Congressional authority and the objections made by members of the Congress, Kmiec concluded, “It is therefore unclear which constitutional power Congress exercised when it acquired Hawaii by joint resolution. Accordingly, it is doubtful that the acquisition of Hawaii can serve as an appropriate precedent for a congressional assertion of sovereignty over an extended territorial sea (p. 252).” There has been no followup opinion from the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel since 1988 that qualified how Congressional legislation could annex foreign territory. If the Department of Justice was unclear as to which constitutional power Congress exercised in 1898 when it purported to have annexed Hawaiian territory by joint resolution, it should still be unclear as to how Congress “has enacted more than 150 statutes that specifically recognize and implement this trust relationship with the Native Hawaiian community, including the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act, the Native Hawaiian Education Act, and the Native Hawaiian Health Care Act” stated in its press release.

It is clear that the Department of Justice had this information since 1988, but for obvious reasons did not cite that opinion in its joint report with the DOI that covered the portion on annexation (p. 26-30). To do so, would have completely undermined all the statutes the Congress has enacted for Hawai‘i, which would also include the lawful authority of the State of Hawai‘i government itself since it was created by an Act of Congress in 1959.

This was precisely the significance of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs CEO Dr. Kamana‘opono Crabbe’s questions to Secretary of State John Kerry. Without any evidence that the United States extinguished the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent and sovereign State under international law, the Hawaiian Kingdom is presumed to still be in existence and therefore under an illegal and prolonged occupation.

So before the “five threshold questions that will be the subject of the forthcoming public meetings regarding whether the Federal Government should reestablish a government-to-government relationship with the Native Hawaiian community” can be answered by the community, the only question that should be posed to the DOI at the public meetings is:

“Since the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel did not respond with evidence to the Office of Hawaiian Affairs CEO Dr. Kamana‘opono’s questions dated May 5, 2014 that the Hawaiian Kingdom does not exist as an independent and sovereign State under international law, I have to presume the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist. Therefore, my question to you is by what authority is the Department of Interior claiming to be here in Hawai‘i, being a foreign sovereign and independent State, since the Department of Justice has already concluded that Congress could not have annexed the Hawaiian Islands by a joint resolution?”

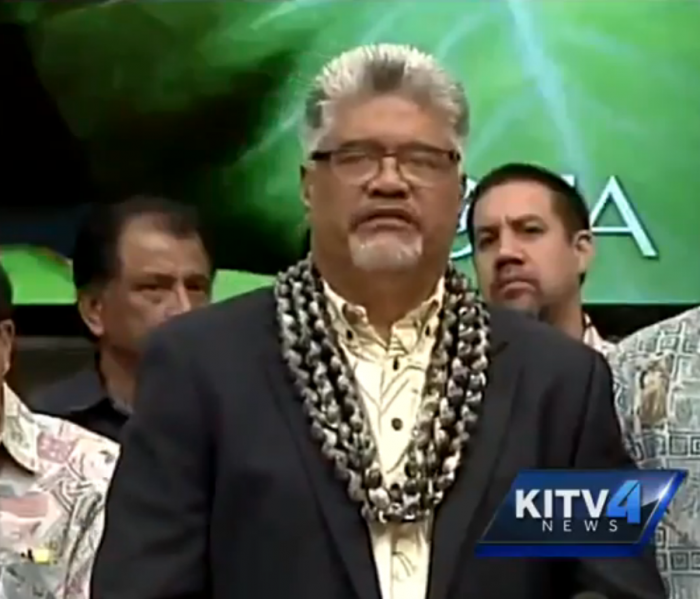

KITV News: Hawaii community responds to feds considering Native Hawaiian recognition

To view KITV news video of the story click here.

HONOLULU —There’s excitement, applause and also some words of caution after the federal government took the first steps toward possibly establishing a government-to-government relationship between the United States and Native Hawaiians.

The federal government says it’s taking its first step toward re-establishing a government-to-government relationship with Native Hawaiians.

The Department of the Interior announced a month long series of meetings with Hawaii residents and they start Monday.

“I think it’s a sign of panic and desperation on the part of the federal government and the Department of Interior,” said Williamson Chang, University of Hawaii law professor.

Under current rules, this can only be done with residents in the lower 48 states. So, the department would first have to change those rules.

Chang says he sees this as being spurred on by the recent letter by Office of Hawaiian Affairs CEO Kamana’o Crabbe to U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry. The letter asked for a legal opinion about Hawaii’s political status under international law.

“So, I think that’s changed the ball game completely. OHA is asking, ‘Are we still a nation?’ And that I think scared them that if there is, this is what’s going on in Hawaii and we have something to worry about,” said Chang.

“Why not go for the sure thing where Hawaiians become like a federally recognized Indian tribe. We know how to deal with them. They’re not going to embarrass us internationally if we do that,” Chang continued.

Chang says they may also be under pressure to do something before President Obama leaves office.

Hawaii’s entire congressional delegation as well as the Governor and OHA’s trustee chair Colette Machado released statements commending the Obama Administration for its commitment to engaging Native Hawaiians in open dialogue.

“… we see this as only one option for consideration. The decision of whether to walk through the federal door or another will be made by delegates to a Native Hawaiian ‘aha and ultimately by our people. We are committed to keeping all doors open so our people can have a full breadth of options from which to choose what is best for themselves and everyone in Hawai’i.”

Public Meetings in Hawaii – June 23 through July 8

Oahu

Monday, June 23 — Honolulu – 9:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m.

Hawaii State Capitol Auditorium

Monday, June 23 — Waimanalo – 6:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m.

Waimanalo Elementary and Intermediate School

Tuesday, June 24 — Waianae Coast – 6:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m.

Nanaikapono Elementary School

Wednesday, June 25 — Kaneohe – 6:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m.

Heeia Elementary School

Thursday, June 26 — Kapolei – 6:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m.

Makakilo Elementary School

Lanai

Friday, June 27 – Lanai City – 6:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m.

Lanai Senior Center

Molokai

Saturday, June 28 – Kaunakakai – 1:00 p.m. to 4:00 p.m.

Kaunakakai Elementary School

Kauai

Monday, June 30 – Waimea – 6:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m.

Waimea Neighborhood Center

Tuesday, July 1 — Kapaa – 6:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m.

Kapaa Elementary School

Hawaii Island

Wednesday, July 2 — Hilo – 6:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m.

Keaukaha Elementary School

Thursday, July 3 — Waimea – 10:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m.

Waimea Community Center

Thursday, July 3 — Kona – 6:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m.

Kealakehe High School

Maui

Saturday, July 5 — Hana – 1:00 p.m. to 4:00 p.m.

Hana High and Elementary School

Monday, July 7 — Lahaina – 6:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m.

King Kamehameha III Elementary School

Tuesday, July 8 — Kahului – 6:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m.

Pomaikai Elementary School

Washington Post: Feds take step toward Native Hawaiian recognition

The Associate Press Reported in the Washington Post.

HONOLULU — The federal government announced Wednesday it will take a first step toward recognizing and working with a Native Hawaiian government at a time when a growing number of Hawaiians are questioning the legality of the U.S. annexation of Hawaii.

The U.S. Department of the Interior will host a series of public meetings during the next 60 days with Native Hawaiians, other members of the public and Native American tribes in the continental U.S. to discuss the complex issue, Rhea Suh, assistant secretary for policy, management and budget for the department, said during a conference call with reporters.

“This does not mean we are proposing an actual formal policy,” Suh said. “We are simply announcing that we’ll begin to have conversations with all relevant parties to help determine whether we should move forward with this process and if so, how we should do it.”

Native Hawaiians have been taking steps to form their own government, but the possibility of federal recognition and a growing sense that many Hawaiians want to pursue independence led some observers to call for a delay in the nation-building process. Kamanaopono Crabbe, the CEO of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, suggested a delay of at least six months after questions were raised about whether the Hawaiian kingdom still exists in the eyes of the United States.

“While a rulemaking process proposed by the DOI is designed to open the door to a government-to-government relationship between the United States and our people, we see this as only one option for consideration,” Crabbe said in a statement. “The decision of whether to walk through the federal door or another will be made by delegates to a Native Hawaiian ‘aha (convention) and ultimately by our people. We are committed to keeping all doors open so our people can have a full breadth of options from which to choose what is best for themselves and everyone in Hawaii.”

Two potential steps — creating a government and seeking federal recognition — can happen at the same time, said Jessica Kershaw, a spokeswoman for the Interior Department.

Critics have said the path the federal government is pursuing is inappropriate because it appears the end goal is to incorrectly recognize Native Hawaiians as a Native American tribe. However, the federal government’s process leaves it up to Hawaiians to define themselves, and there would be discussions about whether it makes sense for Hawaiians to pursue a similar tribal designation, Suh said.

“There is nothing in this process that speaks to how the native community should be defined,” Suh said. “This process only pertains to the relationship between the U.S. government and the native Hawaiian community.”

The community meetings would start next week in Honolulu and would continue on neighboring islands.

Williamson Chang, a law professor at the University of Hawaii, believes the legal questions raised recently about whether the Kingdom of Hawaii still exists pushed the federal government into action.

“I consider Hawaii to be occupied or under a state of emergency,” Chang said. “The one thing I’m sure of is the United States does not have jurisdiction.”

A federal recognition that is similar to a tribal designation would be a step backward in the eyes of many Hawaiians, because the U.S. previously recognized the Hawaiian government as equal, not beneath, the U.S., Chang said.

“One solution could be complete independence, but I don’t think the United States would stand for that,” Chang said. “The Big Island could be spun off and become an independent nation, where Hawaiians could say they have a homeland.”