Category Archives: Education

Dr. Keanu Sai to Start Off United Church of Christ Workshops on Hawaiian Kingdom History on August 7, 2022

Come join the HCUCC Justice and Witness Missional Team for this exciting and informative exploration of Hawaiian History. Whether you are kamaʻāina or a relative newcomer to Hawaiʻi, you will hear history that you have not heard before.

Three eminent scholars, Dr. Keanu Sai, Dr. Ron Williams Jr., and Donovan Preza, will help us delve into historic documents and events that can inform us as we seek understanding and discernment regarding fulfilling our promise made in the UCC’s apology 30 years ago to the Hawaiian people to stand with them in seeking justice.

See and hear newly translated church documents from over a century. Learn about the Hawaiian Kingdomʻs founding and continuing legal status under International law. Learn about the Mahele and privatization of Hawaiian land under Hawaiian Kingdom law and why land issues will continue unless the UCC promise is fulfilled. Learn about churches who actively resisted the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and the white oligarchy who facilitated the illegal overthrow. If as brothers and sisters in Christ we desire reconciliation, we must first acknowledge the nature of the wrongs and their continuing effects on these islands, the Hawaiian people, and our Church.

This 12-week series will be presented through Zoom beginning on Sunday, August 7, 2022, at 4:00 p.m. HST and continues each Sunday, at the same time, through October 23, 2022. Each Zoom session will be one hour long consisting of a presentation followed by questions and discussion.

To attend any or all of the sessions, please register HERE.

PART I: The Kingdom

Presenter: Dr. Keanu Sai

ABOUT THE PRESENTER: I have a Ph.D. in Political Science specializing in Hawaiian Constitutionalism and International Relations, and a founding member of the Hawaiian Society of Law & Politics. I served as lead Agent for the Hawaiian Kingdom in arbitration proceedings before the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague, Netherlands, from November 1999-February 2001. I also served as Agent in a Complaint against the United States of America concerning the prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom, which was filed with the United Nations Security Council on July 5, 2001. Articles on the status of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent state, the arbitration case and the complaint filed with the United Nations Security Council have been published in the following journals: American Journal of International Law, vol. 95 (2001); Chinese Journal of International Law, vol. 2, issue 1, (2002), and the Hawaiian Journal of Law & Politics, vol. 1 (2004).

- AUGUST 7 Hōʻike ʻEkahi (Presentation 1) The importance of terminology. Is Hawaiian a nationality, which is multi-ethnic, or a native indigenous people that have been colonized by the United States?

- AUGUST 14 Hōʻike ʻElua (Presentation 2) The constitutional history of the Hawaiian Kingdom from King Kamehameha III to Queen Lili‘uokalani (1839-1893)

- AUGUST 21 Hōʻike ʻEkolu (Presentation 3) The illegal overthrow of the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State under international law

- AUGUST 28 Hōʻike ʻEhā (Presentation 4) The road to recovery of ending the American occupation. How to bring compliance to the rule of law in light of war crimes and human rights violations committed in the Hawaiian Kingdom since January 16, 1893

PART II: The Church

Presenter: Dr. Ronald Williams Jr.

ABOUT THE PRESENTER: Dr. Ronald Williams Jr. holds a doctorate in history from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa with a specialization in Hawaiʻi and Native-language resources. He is a former faculty member of the Hawaiʻinuiākea School of Hawaiian Knowledge, UH Mānoa and in 2017 was the founding director of the school’s Lāhui Hawaiʻi Research Center. Dr. Williams is also a past president of the 128-year old Hawaiian Historical Society. He currently works as an archivist at the Hawaiʻi State Archives and serves as Hoʻopaʻa Kūʻauhau (Historian) for the grassroots political organization Ka ʻAhahui Hawaiʻi Aloha ʻĀina. Dr. Williams was a contributing author to the 2019 Samuel Manaiākalani Kamakau Book of the Year award-winning publication, Hoʻoulu Hawaiʻi: The Kalākaua Era. He has published in a wide variety of academic and public history venues including the Oxford Encyclopedia of Religion in America, the Hawaiian Journal of History, and Hana Hou! Magazine.

- SEPTEMBER 04 Hōʻike ʻEkahi (Presentation 1) The Early Mission, 1820 -1863

- SEPTEMBER 11 Hōʻike ʻElua (Presentation 2) Hōʻeuʻeu Hou: Sons of the Mission and the Shaping of a New “Mission,” 1863-1888

- SEPTEMBER 18 Hōʻike ʻEkolu (Presentation 3) Poʻe Karitiano ʻOiaʻiʻo (True Christians)

- SEPTEMBER 25 Hōʻike ʻEhā (Presentation 4) “I ka Wā Mamua, ka Wā Mahope” (The Future is in the Past)

PART III: The Land

Presenter: Donovan Preza MORE INFO TO COME

- OCTOBER 2 Hōʻike ʻEkahi (Presentation 1)

- OCTOBER 9 Hōʻike ʻElua (Presentation 2)

- OCTOBER 16 Hōʻike ʻEkolu (Presentation 3)

- OCTOBER 23 Hōʻike ʻEhā (Presentation 4)

Land Titles Throughout the Hawaiian Islands are Defective – Filing A Claim Under Your Title Insurance Policy

The Preliminary Report on the Legal Status of Land Titles throughout the Realm of July 16, 2020, by the Royal Commission of Inquiry, is a comprehensive report as to why the majority of land titles today throughout Hawai‘i are defective. This includes properties claimed to be owned by billionaires such as Mark Zuckerberg’s claim to property on the island of Kaua‘i, and Larry Ellison’s claim to 98% of the island of Lana‘i. The Royal Commission of Inquiry also published a Supplemental Report on Title Insurance on October 20, 2020.

All titles to real estate throughout the Hawaiian Kingdom are subject to Hawaiian laws despite the unlawful overthrow of its government by the United States in 1893. As such, all titles that have since been alleged to have been conveyed after January 17, 1893, are void ab initio due to forged certificates of acknowledgment by individuals impersonating public officers. This includes all purported conveyances of Government or Crown lands after January 17, 1893, and any judicial proceedings regarding titles to land.

Hawaiian law, however, would have recognized these acts of the insurgents as being valid if Queen Lili‘uokalani was restored to office. The agreed upon conditions of restoration between the United States and the Hawaiian Kingdom provided, “a general amnesty to those concerned in setting up the provisional government and a recognition of all its bona fide acts and obligations.” Regarding the “bona fide acts and obligations,” the Queen stated in her letter dated December 18, 1893, to the U.S. Minister Albert Willis, who was negotiating on behalf of President Cleveland, “I further solemnly pledge myself and my Government, if restored, to assume all the obligations created by the Provisional Government, in the proper course of administration, including all expenditures for military or police services, it being my purpose, if restored, to assume the Government precisely as it existed on the day when it was unlawfully overthrown.”

By this agreement, the United States acknowledged the acts done by the insurgency were not “bona fide” until after the Queen was restored. The Queen was not restored and, therefore, the insurgency continued to unlawfully impersonate public officers of the Hawaiian Kingdom in the chain of title. These defects in title are covered risks in the owner’s and lender’s title insurance policies as:

- forgery, fraud, undue influence, duress, incompetency, incapacity, or impersonation;

- failure of any person or Entity to have authorized a transfer or conveyance;

- a document affecting Title not properly created, executed, witnessed, sealed, acknowledged, notarized, or delivered;

- a document executed under a falsified, expired, or otherwise invalid power of attorney;

- a document not properly filed, recorded, or indexed in the Public Records including failure to perform those acts by electronic means authorized by law;

- a defective judicial or administrative proceeding.

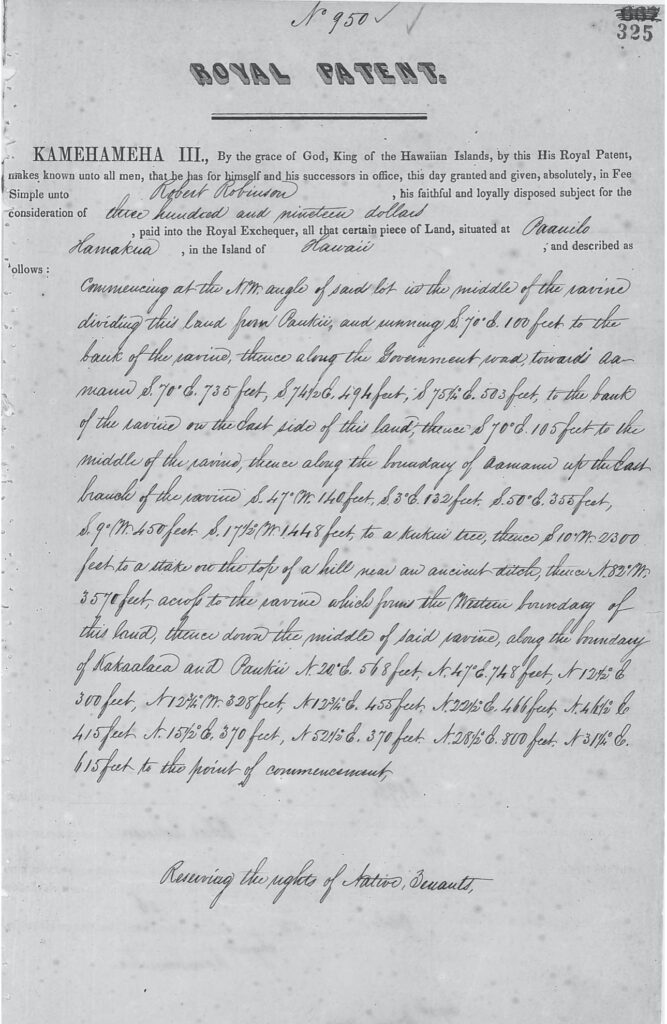

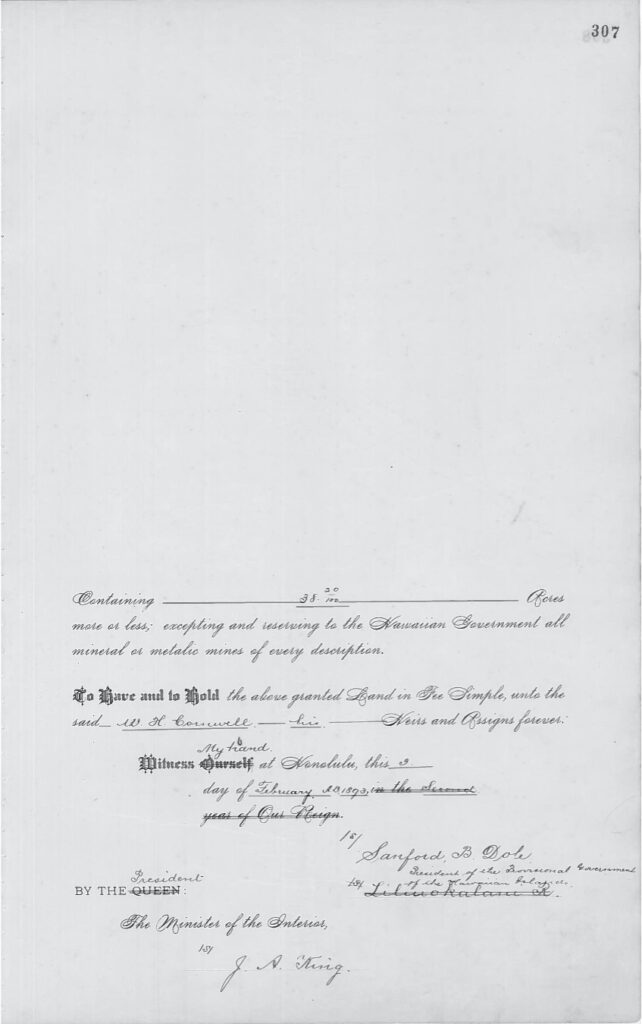

Here’s an example of a “bona fide” Royal Patent issued on October 26, 1852.

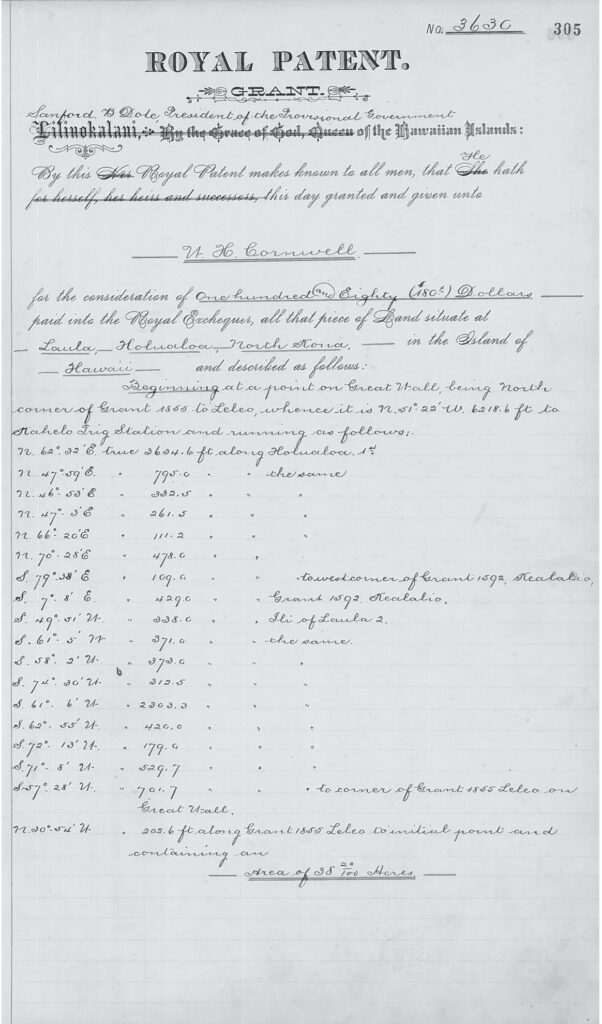

Here is an example of a “forged” Royal Patent issued just one month after the overthrow of the Hawaiian government by the United States dated February 3, 1893. This is an example of what President Cleveland sought to remedy as a “bona fide” act by the insurgents in his agreement of restoration with Queen Lili‘uokalani.

Any property today that derives from this forged Royal Patent is void, but the loss could be covered by an owner’s policy of title insurance. Hill, Steindorff and Widener, in their “Recent Developments in Title Insurance Law,” reported that in 2012, a California Federal District Court, in Gumapac v. Deutsche Bank National Trust, found that “a title report revealed a defect of title by virtue of an executive agreement between President Grover Cleveland and Queen Lili‘uokalani of the Hawaiian Kingdom that rendered any notary actions unlawful. Thus, the deed of conveyance to the homeowners was nullified.” In Hawai‘i, claimants under both an owner’s or lender’s title insurance policy have a duty to immediately notify their insurer of any title defects that affect title to the property or the mortgage that secures the repayment of a loan.

During this time of high prices at the gas pump added on to the high cost of living in the Hawaiian Islands, watching how you spend your money is critical to surviving during this inflation crisis brought upon the residents of Hawai‘i by the United States prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom since 1893. But there is some monetary light that many people in Hawai‘i can take advantage of, which is filing a claim with their title insurance company under an owner’s policy, and notifying your bank or lender to file a claim so that your debt owed to the lender is paid off.

When individuals want to borrow money from a bank or lender, they are told by the lender to first go to an escrow company to purchase a lender’s title insurance policy in the amount to be borrowed. Prior to the issuing of a title insurance policy, the escrow company does a title search on the property that the borrower intends to use as a security instrument, also called a mortgage, to ensure the repayment of the loan. A title insurance company that works with the escrow company will then insure the accuracy of the title search. Only when the borrower purchases the title insurance policy to protect the lender from any title defect that affects the mortgaged debt is when escrow comes to a close.

There is another type of title insurance policy that is issued by the escrow company and that is an owner’s policy that protects the owner and not the lender. An owner’s policy is normally purchased when an individual borrows money for the first time and has to go to an escrow company. Many people don’t even know that they may have purchased an owner’s policy unless they look at their closing papers from escrow. Unlike a lender’s policy that covers the debt owed to the lender, an owner’s policy covers the owner’s loss, which is the appraised value of the property at the time the policy is taken out.

Most people are unaware as to what title insurance is and how it works. Typical insurance policies, such as car insurance or flood insurance, insure against a future cause of damage, that may or may not occur. Title insurance, on the other hand, insures against a past cause of damage called defects in the chain of title that affect ownership of real property. According to Burke’s Law of Title Insurance, title insurance is an agreement to indemnify the insured for losses incurred “by either on-record and off-record defects that are found in the title or interest in an insured property to have existed on the date on which the policy is issued.” And Black’s Law Dictionary defines title insurance as a “policy issued by a title company after searching the title…and insuring the accuracy of its search against claims of title defects.” As the Florida Court of Appeals, in McDaniel v. Lawyers Title Guar. Fund, stated, “One of the reasonable expectations of a policyholder who purchases title insurance is to be protected against defects in his title which appear of record.”

Title insurance is a one-time paid premium agreement under both an owner’s policy, that protects the interests of the owner of the property, and a lender’s policy, that protects the lender’s interest—the debt owed—in the mortgaged lien on the property. The owner’s policy does not exceed the amount of coverage on the policy. The lender’s policy coverage reduces as the debt is being paid by the borrower, which will eventually expire once the final payment of the loan is made. Burke explains that coverage under an owner’s policy, however, “lasts for as long as the insured has some liability for title defect, whether as the present owner or possessor, or as a vendor [grantor] and warrantor of the state of the title upon some later sale. There is no such thing as term title insurance. Its policy might, potentially, last forever.” A grantor’s covenant is explicitly stated in its warranty deed where it states, “and that the Grantor will WARRANT AND DEFEND the same unto the Grantee against the lawful claims and demands of all persons.”

Being that title insurance is an indemnity agreement, Burke states that the insurer can also act as a surety, which “is a person agreeing to be answerable for the actions of another.” According to Burke, when there is a breach of covenant and warranty of title by a grantor, the “title insurer might agree to remedy a breach of the covenant for further assurances by bringing the litigation required to cure a title, instead of letting the [grantor] do it.” The right to remedy, as a surety, is provided under Condition no. 5 of both the owner and lender policies that states the insurer “shall have the right, in addition to the options contained in Section 7 of these Conditions, at its own cost, to institute and prosecute any action or proceeding or to any other act that in its opinion may be necessary or desirable to establish the Title, as insured, or to prevent or reduce loss or damage to the Insured.” According to Hill, Steindorff and Widener, an Illinois Appellate Court concluded “that although the title company did not have an ownership interest in the property, the company had issued a title insurance policy and could have redeemed the taxes on the subject property on behalf of the prior owner, to whom it had issued a title policy.”

When the title insurance company is given the evidence of proof of loss of title in a claim letter by the insured, the company has thirty-days to either initiate proceedings to remedy the defect of the title or make a payment to the insured covered in the insurance policy. According to the federal court in Davis v. Stewart Title Guaranty Co., “In law, a title is either good or bad.” The Missouri Supreme Court, in Kent & Obear v. Allen, stated, “the validity of the title arising, the question must be determined whether it is good or bad. We cannot object to the title of the respondent that it is doubtful or unmarketable.” The Davis court also concluded that the “liability of the insurer was definitely fixed under the terms of the policy,” to either remedy the defect or the “payment of loss was due, under the policy, ‘within 30 days thereafter.’”

To determine “on-record defects in title,” a title insurer relies on a competent title search. According to Baker, Miceli, Sirmans, and Turnbull’s article, “Optimal Title Search,” in the Journal of Legal Studies, “Some states have no set length but instead require that the entire title history of a parcel of land be searched back to the state’s date of patent,” which include Alaska, Arizona, California, Florida, Idaho, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, North and South Dakota, Oregon, Texas and Washington. At the highest number of years for a title search are Colorado, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, North and South Dakota, and Wyoming at 187 years. At the low end of a 30-year search are New Mexico, Oklahoma and Tennessee. In a study of optimal title searches, Hawai‘i, Illinois and Indiana were excluded from the analysis because they provided “indeterminate search lengths.”

In one particular preliminary report by Title Guaranty of Hawai‘i, its title search only went back one conveyance. This lack of a full title search by Title Guaranty, who serves as an agent for title insurance companies, back to the original patent, called Royal Patents, only amplifies the purpose of title insurance as an indemnity agreement. It is not a guaranty of the state of the title. According to the Pennsylvania court, in Hicks v. Saboe, “The purpose of title insurance is to protect the insured…from loss arising from defects in the title which he acquires.” The federal court, in Omega Healthcare Investors, Inc. v. First Am. Title Ins. Co., stated, “Because title insurance [is] a contract of indemnity, the insurer does not guarantee the state of the title, but agrees to pay for any loss resulting from a defective title.” The Maryland Appeals Court, in Stewart Title Guar. Co. v. West, explained that a title insurer does not have a duty to advise “on the state of title to the property, but to insure against…loss resulting from any defects.” Therefore, “the title insurer does not ‘guarantee’ the status of the grantor’s title. As an indemnity agreement, the insurer agrees to reimburse the insured for loss or damage sustained as a result of title problems, as long as the coverage for the damages incurred is not excluded from the policy.”

Since 1994, the State of Hawai‘i courts have applied, whenever the issue of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s continued existence as a State arose in court proceedings, the State of Hawai‘i v. Lorenzo case at the Intermediate Court of Appeals (ICA), which has come to be known as the Lorenzo doctrine in the federal courts. For 28 years, both the State of Hawai‘i courts and the federal courts have been applying the Lorenzo doctrine wrong. Under international law, which the ICA acknowledged may affect its rationale of placing the burden on the defendant to prove the Hawaiian Kingdom “exists as a State,” shifts the burden on the party opposing the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom that it “does not exist as a State.” In international arbitration proceedings at the Permanent Court of Arbitration from 1999-2001, in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, PCA case no. 1999-01, the PCA acknowledged the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist as a State and the Council of Regency as its government. Because the Hawaiian Kingdom still exists, so do the laws that apply to real property.

In a denial letter to a title insurance claimant, Michael J. Moss, Senior Claims Counsel for Chicago Title Insurance Company, specifically referenced the Lorenzo doctrine applied in two State of Hawai‘i court cases and one federal court case as a basis to decline the insurance claim under an owner’s title insurance policy in the amount of $178,000.00. Moss stated:

The Hawaiian Courts have consistently found that the Kingdom of Hawai‘i is no longer recognized as a sovereign state by either the federal government or by the State of Hawai‘i. See State v. Lorenzo, 77 Hawai‘i 219, 221, 883 P.2d 641, 643 (Haw.App.1994); accord State v. French, 77 Hawai‘i 222, 228, 883 P.2d 644, 649 (Haw.App.1994); Baker v. Stehua, CIV 09-00615 ACK-BMK, 2010 WL 3528987 (D. Haw. Sept. 8, 2010).

Like the courts of the State of Hawai‘i and the federal courts, the Senior Claims Counsel incorrectly applied the Lorenzo doctrine, which should have been in favor of the title insurance claimant. The title insurance claim was that the “Owner’s deed was not lawfully executed according to Hawaiian Kingdom law [because] the notaries public and the Bureau of Conveyance weren’t part of the Hawaii[an] Kingdom, that the documents in [the claimant’s] chain of title were not lawfully executed.” In other words, the Lorenzo doctrine, when applying international law correctly, would compel the title insurance company to pay the claimant his $178,000.00 covered under the owner’s title insurance policy he had purchased to protect him in case there was a defect in the title.

To find out if you have an owner’s policy check your closing papers from escrow to see if you purchased a policy. Or you can call your escrow company or companies that you went to in the past. If you have a mortgage you did purchase a title insurance policy to protect the lender. To file a claim under your owner’s policy download this MSWord document and fill in the necessary information after you have your owner’s policy in hand. To send a letter to your lender to file an insurance claim under the lender’s policy you purchased download this MSWord document and fill in the necessary information.

Submitting an insurance claim is a private matter that is subject to the terms of your contract or policy. Under the terms of the policy you and the lender are obligated to notify the insurance company if you have been made aware that there are defects in your title. It is suggested that you carefully read over your title insurance policy before you send your claim to the insurance company by certified mail. The lender, not the borrower, has a copy of the lender’s policy that was purchased by the borrower. Once the claim, whether by the owner or the lender, is received by the insurance company you will receive a letter acknowledging your claim and assigning it a claim number. This letter by the insurance company will begin the thirty-day window to either remedy the defect in the title or pay the amount covered under the policy.

The Far Reach of the Lorenzo Doctrine—The Title Insurance Industry

The Lorenzo doctrine was adopted by the federal courts in the Ninth Circuit for jurisdictional purposes but it has been used in the land title insurance industry for denying insurance claims.

In 1994, the State of Hawai‘i Intermediate Court of Appeals (“ICA”) heard an appeal where the defendant-appellant, Anthony Lorenzo, was seeking an appeal that the trial court committed an error when his motion to dismiss his indictment was denied, which led to his conviction. Lorenzo argued that the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist because the overthrow of the Hawaiian government on January 17, 1893, was illegal. And since he was a citizen of the kingdom, the trial court did not have any jurisdiction over him. The case was State of Hawai‘i v. Lorenzo.

For the first time ever regarding the United States overthrow, the ICA distinguished the government from a sovereign State—the Hawaiian Kingdom, or at least tried to. In the past, these two terms were interchangeable. In its decision, the ICA cited a 1991 appeals case that was heard by the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, Klinghoffer v. S.N.C. Achille Lauro, 937 F.2d 44, 47 (2d Cir. 1991) that quoted another case in the Second Circuit, National Petro-chemical Co. v. M/T Stolt Sheaf, 860 F.2d 551, 553 (2d Cir. 1988), as well as quoting from §201 from the Restatement (Third) of the Foreign Relations Law of the United States (1987). The Second Circuit Court stated:

The [Palestine Liberation Organization] PLO first argues that it is a sovereign state and therefore immune from suit under the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (the “FSIA”), 28 U.S.C. § 1602 et seq. (1988). As support for this argument, it relies on its “political and governmental character and structure, its commitment to and practice of its own statehood, and its unlisted and indeterminable membership.” Brief for Appellant at 7. However, this Court has limited the definition of “state” to “‘entit[ies] that ha[ve] a defined territory and a permanent population, [that are] under the control of [their] own government, and that engage[] in, or ha[ve] the capacity to engage in, formal relations with other such entities.’” [citations omitted]. It is quite clear that the PLO meets none of those requirements.

The definition of a State includes a government and not that the government is synonymous with a State. Palestine has yet to be recognized by the United States as a sovereign and independent State, which prevented the PLO from claiming that Palestine is a State in U.S. federal courts. Therefore, whenever the issue of Palestine arises in federal court proceedings, the court itself or one of the parties to the lawsuit would invoke the “political question doctrine” and the case would be dismissed. Only until the United States recognizes Palestine as a State will the federal courts acknowledge Palestinian Statehood.

The Hawaiian Kingdom is different from the Palestinian situation in that the United States already recognized the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State in its treaties. In other words, the Hawaiian Kingdom did “ha[ve] a defined territory and a permanent population, [that are] under the control of [their] own government, and that engage[] in, or ha[ve] the capacity to engage in, formal relations with other such entities.” In fact, the Hawaiian Kingdom had an embassy in Washington, D.C., and the United States had an embassy in Honolulu.

The question that came before the ICA in the Lorenzo appeal is whether the State continues to exist despite the overthrow of its government by the United States on January 17, 1893. The ICA stated, “The essence of the lower court’s decision is that even if, as Lorenzo contends, the 1893 overthrow of the Kingdom was illegal, that would not affect the court’s jurisdiction in this case. Although the court’s rationale is open to question in light of international law, the record indicates that the decision was correct because Lorenzo did not meet his burden of proving his lack of jurisdiction.” Here, the ICA would appear to have conflated the Hawaiian State with the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom when it stated, “the 1893 overthrow of the Kingdom was illegal.”

This distinction between the State and the government was explained in the Restatement (Third) of the Foreign Relations Law of the United States that the ICA cited. In §202 is states:

Recognition of state and government distinguished. Recognition of a state is a formal acknowledgment that the entity possesses the qualifications of statehood, and implies a commitment to treat the entity as a state. Recognition of a government is formal acknowledgment that a particular regime is the effective government of a state and implies a commitment to treaty that regime as the government of that state. Ordinarily, that occurs when a state is incorporated into another state, as when Montenegro in 1919 became a part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (later Yugoslavia).

According to Professor Oppenheim, once recognition of a State is granted, it “is incapable of withdrawal” by the recognizing State, and Professor Schwarzenberger explains that “recognition estops the State which has recognized the title from contesting its validity an any future time.” §202 goes on to say that the “duty to treat a qualified entity as a state also implies that so long as the entity continues to meet those qualifications its statehood may not be ‘derecognized.’ If the entity ceases to meet those requirements, it ceases to be a state and derecognition is not necessary.”

So because the Hawaiian State cannot be “derecognized,” it would continue to exist despite the overthrow of the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom on January 17, 1893. Evidence of “when a state is incorporated into another state” would be an international treaty, particularly a peace treaty, whereby the Hawaiian Kingdom would have ceded its territory and sovereignty to the United States. Examples of foreign States ceding sovereign territory to the United States by a peace treaty include the 1848 Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits, and Settlement with the Republic of Mexico that ended the Mexican-American war, and the 1898 Treaty of Peace between the United States of America and the Kingdom of Spain that ended the Spanish-American War.

The 1898 Joint Resolution To provide for annexing the Hawaiian Islands to the United States, is a municipal law of the United States without extraterritorial effect. It is not an international treaty. Under international law, to annex territory of another State is a unilateral act, as opposed to cession, which is a bilateral act between States.

In 2002, the federal court in Honolulu, in United States v. Goo, referred to the State of Hawai‘i v. Lorenzo and the Lorenzo doctrine. For 28 years both the State of Hawai‘i courts and the federal courts have been applying the Lorenzo doctrine wrong. Under international law, which the ICA in Lorenzo acknowledged may affect the rationale of the ICA in placing the burden on the defendant to prove the Hawaiian Kingdom “exists as a State,” shifts the burden on the party opposing the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom that it “does not exist as a State.”

When the ICA acknowledged that Lorenzo did state in his motion to dismiss the indictment that the Hawaiian Kingdom “was recognized as an independent sovereign nation by the United States in numerous bilateral treaties,” it set the presumption to be the Hawaiian Kingdom’s existence as a State under international law and not the existence of the State of Hawai‘i as a political subdivision of the United States.

Under international law, it was not the burden of the defendant to provide evidence that the Hawaiian Kingdom “exists as a State” when the Lorenzo Court already acknowledged its existence and recognition by the United States. Rather, it was the burden of the prosecution to provide evidence that the Hawaiian Kingdom “does not exist as a State.” As a result, the Lorenzo Court’s ruling was wrong and all decisions that followed in State of Hawai‘i courts and federal courts applying the Lorenzo doctrine also were wrong.

The Lorenzo doctrine also has been used by the title insurance industry. In a denial letter to a title insurance claimant, Michael J. Moss, Senior Claims Counsel for Chicago Title Insurance Company, specifically referenced the Lorenzo doctrine applied in two State of Hawai‘i court cases and one federal court case as a basis to decline the insurance claim under an owner’s title insurance policy in the amount of $178,000.00. Moss stated:

The Hawaiian Courts have consistently found that the Kingdom of Hawai‘i is no longer recognized as a sovereign state by either the federal government or by the State of Hawai‘i. See State v. Lorenzo, 77 Hawai‘i 219, 221, 883 P.2d 641, 643 (Haw.App.1994); accord State v. French, 77 Hawai‘i 222, 228, 883 P.2d 644, 649 (Haw.App.1994); Baker v. Stehua, CIV 09-00615 ACK-BMK, 2010 WL 3528987 (D. Haw. Sept. 8, 2010).

Like the courts of the State of Hawai‘i and the federal courts, the Senior Claims Counsel incorrectly applied the Lorenzo doctrine, which should have been in favor of the title insurance claimant. The title insurance claim was that the “Owner’s deed was not lawfully executed according to Hawaiian Kingdom law [because] the notaries public and the Bureau of Conveyance weren’t part of the Hawaii[an] Kingdom, that the documents in [the claimant’s] chain of title were not lawfully executed.”

In other words, the Lorenzo doctrine, when applying international law correctly, would force the title insurance company to pay the claimant his $178,000.00 covered under the owner’s title insurance policy he had purchased to protect him in case there was a defect in the title.

All titles to property that were conveyed after January 17, 1893, are defective because the deeds were “not lawfully executed according Hawaiian Kingdom law [because] the notaries public and the Bureau fo Conveyances weren’t part of the Hawaii[an] Kingdom, [and] that the documents in [the claimant’s] chain of title were not lawfully executed.”

Defective titles to land in Hawai‘i also renders all mortgages tied to the land to be void and that title insurance also pays off the balance of the loan to the bank under the Lender’s Policy. For more information on this topic, download the Royal Commission of Inquiry’s Preliminary Report on Land Titles Throughout the Realm and its Supplemental Report on Title Insurance.

Setting the Record Straight on Descendants of Kamehameha I and Heirs to the Hawaiian Crown

There is a common misunderstanding that if you are a direct descendent of Kamehameha I today you are an heir to the throne as well as an heir to the Crown Lands. This is incorrect.

It is true that Kamehameha I had many wives. According to the second revised edition of the book Kamehameha’s Children Today by Charles Ahlo, Rubellite Kawena Kinney Johson, and Jerry Walker, Kamehameha I had 30 wives, 18 of whom had 35 children. The other 12 did not have any children. Of the 18 was Keōpūolani who gave birth to Liholiho, who later succeeded to the throne as Kamehameha II in 1819, Kauikeaouli, who succeeded to the throne as Kamehameha III in 1824, and a daughter, Nahiʻenaʻena who died in 1836 while her brother Kamehameha III was King. Of all the wives, she had the highest chiefly rank and she was acknowledged as such by Kamehameha’s Chiefs.

The Kamehameha extended family was not the leadership of the kingdom. Rather, the leadership of the Island of Kingdom of Hawai‘i was comprised of Kamehameha as its Ali‘i Nui (King) and his most trusted Chiefs, which included Kalaʻimamahu, Chief of Hāmākua, Ke‘eaumoku, Chief of Kona, Ka‘iana, Chief of Puna, and Kame‘eiamoku, Chief of Kohala. After defeating the Maui Kingdom of Kalanikupule in 1795 and acquiring the Kaua‘i Kingdom from Kaumuali‘i in 1810, the leadership of Chiefs increased due to the acquisition of additional islands of his expanded domain. These Chiefs extended from Kamehameha’s Chiefs, while the Kamehameha Dynasty extended from the children of Keōpūolani and not from the other 17 wives who had children. The decision of which wife’s children were to be the heirs to the throne was not the decision for Kamehameha I to make on his own. It had to be sanctioned by his Council of Chiefs. Without the support of his Chiefs, Kamehameha’s kingdom would be fractured after his death.

As Kuykendal wrote, “The desertion of Kaʻiana [in 1795], the revolt of Nāmākēhā [in 1796], and Kaumuialiʻi’s dalliance with the Russians [in 1817] were overt acts showing clearly how unwillingly some of the chiefs submitted to his authority.” The Russian explorer, Lieutenant Otto von Kotzebue, who arrived in the islands in 1816 and 1817, was made aware of Kamehameha’s concerns of the longevity of his kingdom. In his 1821 book, Voyage of Discovery, Kotzebue states of a proposed division of the kingdom with Kalanimoku having O‘ahu, Ke‘eaumoku having Maui, Kaumuali‘i retaining Kaua‘i, and Liholiho, Kamehameha’s heir, having Hawai‘i island. Kamehameha took the necessary steps to prevent such breakup from happening. According to Kamakau, Kamehameha sought to strengthen the British alliance because he believed the British supported his dynasty. He was correct.

On May 18, 1824, Kamehameha II arrived in London with the Hawaiian royal retinue that included Mataio Kekūanāo‘a husband to Kamehameha II’s sister, Kīnaʻu. Before the King could meet with King George IV he and his wife Queen Kalama died of measles. High Chief Boki was the highest ranking Chief and he and the royal retinue met with King George IV. According Kekuanao‘a:

The King then asked Boki what was the business on which you and your King came to this country?

Then Boki declared to him the reason of our sailing to Great Britain We have come to confirm the words which Kamehameha I gave in charge to Vancouver thus—“Go back and tell King George to watch over me and my whole Kingdom. I acknowledge him as my landlord and myself as tenant (or him as superior and I inferior). Should the foreigners of any other nation come to take possesion of my lands, then let him help me.”

And when King George had heard he thus said to Boki, “I have heard these words, I will attend to the evils from without. The evils within your Kingdom it is not for me to regard; they are with yourselves. Return and say to the King, to Kaahumanu and to Kalaimoku, I will watch over your country, I will not take possession of it for mine, but I will watch over it, lest evils should come from others to the Kingdom. I therefore will watch over him agreeably to those ancient words.”

Kamehameha II’s body arrived in Lahaina on May 4, 1825. After the funeral and time of mourning had passed, the Council of Chiefs met on June 6, 1824, in Honolulu with Lord Byron and the British Consul. It was confirmed that Liholiho’s brother, Kauikeaouli, was to be Kamehameha III, but since he was only eleven years old, Ka‘ahumanu would continue to serve as Regent and Kalanimōkū as Premier. Kalanimōkū addressed the Council “setting forth the defects of many of their laws and customs, particularly the reversion of lands” to a new King for redistribution and assignment. The chiefs collectively agreed to forgo this ancient custom, and the lands were maintained in the hands of the original tenants in chief and their successors, subject to reversion only in times of treason. Lord Byron was invited to address the Council, and without violating his specific orders of non-intervention in the political affairs of the kingdom, he prepared eight recommendations on paper and presented it to the chiefs for their consideration.

1. That the king be head of the people.

2. That all the chiefs swear allegiance.

3. That the lands descend in hereditary succession.

4. That taxes be established to support the king.

5. That no man’s life be taken except by consent of the king or regent and twelve chiefs.

6. That the king or regent grant pardons at all times.

7. That all the people be free and not bound to one chief.

8. That a port duty be laid on all foreign vessels.

Lord Byron introduced the fundamental principles of British governance to the chiefs and set them on a course of national consolidation and uniformity. His suggestions referred “to the form of government, and the respective and relative rights of the king, chiefs, and people, and to the tenure of lands,” but not to a uniform code of laws. Since the death of Kamehameha in 1819, the Hawaiian Kingdom, as a feudal autocracy, had no uniform system of laws systematically applied throughout the islands. Rather it fell on each of the tenants in chief and their designated vassals to be both lawmaker and arbiter over their own particular tenants living on the granted lands from the King.

When the Hawaiian Kingdom was transformed into a constitutional monarchy, written laws became the legal foundation for the kingdom. Confirming that only the children of Keōpūolani were the heirs to the Throne, the 1840 Constitution stated:

The origin of the present government, and system of polity, is as follows: KAMEHAMEHA I, was the founder of the kingdom, and to him belonged all the land from one end of the Islands to the other, though it was not his own private property. It belonged to the chiefs and people in common, of whom Kamehameha I was the head, and had the management of the landed property. Wherefore, there was not formerly, and is not now any person who could or can convey away the smallest portion of land without consent of the one who had, or has the direction of the kingdom.

These are the persons who have had the direction of it from that time down, Kamehameha II, Kaahumanu I, and at the present time Kamehameha III. These persons have had the direction of the kingdom down to the present time, and all documents written by them, and no others are the documents of the kingdom.

The kingdom is permanently confirmed to Kamehameha III, and his heirs, and his heir shall be the person whom he and the chiefs shall appoint, during his life time, but should there be no appointment, then the decision shall rest with the chiefs and house of Representatives.

In the 1852 Constitution, Article 25 states:

The crown is hereby permanently confirmed to His Majesty Kamehameha III during his life, and to his successor. The successor shall be the person whom the King and the House of Nobles shall appoint and publicly proclaim as such, during the King’s life; but should there be no such appointment and proclamation, then the successor shall be chosen by the House of Nobles and the House of Representatives in joint ballot.

In the 1864 Constitution, Article 22 states:

The Crown is hereby permanently confirmed to His Majesty Kamehameha V, and to the Heirs of His body lawfully begotten, and to their lawful Descendants in a direct line; failing whom, the Crown shall descend to Her Royal Highness the Princess Victoria Kamamalu Kaahumanu, and their heirs of her body, lawfully begotten, and their lawful descendants in a direct line. The Succession shall be to the senior male child, and to the heirs of his body; failing a male child, the succession shall be to the senior female child, and the heirs of her body. In case there is no heir as above provided, then the successor shall be the person whom the Sovereign shall appoint with the consent of the Nobles, and publicly proclaim as such during the King’s life; but should there be no appointment and proclamation, and the Throne should become vacant, then the Cabinet Council, immediately after the occurring of such vacancy, shall cause a meeting of the Legislative Assembly, who shall elect by ballot some native Aliʻi of the Kingdom as Successor to the Throne; and the Successor so elected shall become a new Stirps for a Royal Family; and the succession from the Sovereign thus elected, shall be regulated by the same law as the present Royal Family.

According to this constitutional provision, the Kamehameha Dynasty would continue if Kamehameha V had “Heirs of His body lawfully begotten.” The term “lawfully begotten” is a child born in wedlock. A child born out of wedlock was called a bastard child. Kamehameha was not married, and he had no children. In that case, his sister Princess Victoria Kamamalu Kaahumanu would be the successor to the Throne should Kamehameha V not “appoint [a successor to the throne] with the consent of the Nobles, and publicly proclaim as such during the King’s life.” She never married before her death on May 29, 1866, leaving the successor to the Throne to be decided by Kamehameha V. The are some who claim that the Princess had a child. Whether this is true or not, it does not matter because the Constitution states that a child shall be “lawfully begotten,” which can only happen if the child is born in wedlock. The Princess was never married.

When Kamehameha V died on December 11, 1872, he did not appoint a successor and receive confirmation by the Nobles. This was precisely why the Cabinet of Kamehameha V, serving as a Council of Regency, stated to the Legislative Assembly on January 8, 1873, when it was convened in extraordinary session to elect a successor to the throne:

His Majesty left no Heirs.

Her late Royal Highness the Princess Victoria Kamamalu Kaahumanu, to whom in the event of the death of His late Majesty without heirs, the Constitution declared that the Throne should descend, died, also without heirs, on the twenty-ninth day of May, in the year of Our Lord One Thousand Eight Hundred and Sixty-six.

His late Majesty did not appoint any successor in the mode set forth in the Constitution, with the consent of the Nobles or make a Proclamation thereof during his life. There having been no such appointment or Proclamation, the Throne became vacant, and the Cabinet Council immediately thereupon considered the form of the Constitution in such case made and provided.

There is no doubt that there are descendants of Kamehameha I from his 17 wives, other than Keōpūolani. Ahlo, Johnson and Walkerʻs book Kamehameha’s Children Today reveals that. There is no dispute.

These descendants, however, which include Ahlo, Johnson and Walker, are not a part of the Kamehameha Dynasty that headed the government from 1791, after the death of High Chief Keōua, until the death of Kamehameha V in 1872. Those children and grandchildren that headed the Hawaiian government as an absolute monarchy to a constitutional monarchy were Kamehameha II, Kamehameha III, Kamehameha IV and Kamehameha V. The Kamehameha Dynasty was succeeded by the Lunalilo Dynasty in 1873, and the Kalākaua Dynasty replaced the Lunalilo Dynasty in 1874. In 1922, the Kalākaua Dynasty ended with the passing of Prince Jonah Kuhio Kalaniana‘ole.

The Lunalilo and Kalākaua Dynasties descended from Kamehameha Iʻs Chiefs, which are part of the nobility class of the Hawaiian Kingdom. The genealogies published throughout 1896 in the Maka‘anana newspapers reveal the families of the nobility class. To access these genealogies go to The Three Estates of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

Kanaka Express 2022: Understanding the Hawaiian Kingdom v. Biden Federal Lawsuit

Presently the Hawaiian Crown is Not Inheritable but Rather Subject to an Election by the Legislative Assembly after the U.S. Occupation Comes to an End

During this time of the rising of the national consciousness of the Hawaiian Kingdom after over a century of the war crime of denationalization through Americanization, it is important for Hawaiian subjects to understand the laws of the country as they existed prior to the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government on January 17, 1893. Especially the laws that apply to the Hawaiian Crown.

There is a common misunderstanding that the Hawaiian Crown is hereditary. This is not an accurate understanding of Hawaiian constitutional law. Hereditary descent is a part of Hawaiian law, but it works in tandem and within the limits of Hawaiian constitutional law.

Individuals claiming Hawaiian Titles of Nobility, which include Abigail Kawananakoa, Owana Salazar, Mahealani Ahsing, Windy Lorenzo, Ruth Bolomet, just to name a few, are not who they claim. There is a distinction between Titles of Nobility and noble lineage. The former derives from a sitting Monarch, while the latter is a status by virtue of chiefly genealogy called mo‘o ku‘auhau. This is not to say that these individuals are not of noble lineage. Rather the titles they claim are self-declared that have no basis under Hawaiian constitutional law.

Only a sitting Monarch can nominate an heir apparent to the Throne, which will then require confirmation by the Nobles in the Legislative Assembly. The history of Hawaiian Monarchs began with the Kamehameha Dynasty that ended in 1873, followed by the Lunalilo Dynasty that ended in 1874, and then finally the Kalākaua Dynasty that ended in 1922.

In the latter part of the eighteenth century, the northern archipelago of islands consisted of four distinct kingdoms: Hawai‘i Island under Kamehameha I; Maui Island with its dependent islands of Lāna‘i and Kaho‘olawe under Kahekili; Kaua‘i Islalnd and its dependent island of Ni‘ihau under Kā‘eo; and O‘ahu Island with its dependent island of Molokaʻi under Kahahana. Kamehameha, King of Hawai‘i Island, consolidated the four kingdoms establishing the Kingdom of the Sandwich Islands in 1810, which later became the Kingdom of the Hawaiian Islands. In 1829, the Kingdom of the Sandwich Islands came to be known as the Kingdom of the Hawaiian Islands. By 1840, the Kingdom of the Hawaiian Islands came to be known as the Hawaiian Kingdom, a constitutional monarchy.

The Kamehameha Dynasty

Kamehameha I governed his kingdom according to ancient tradition and strict religious protocol. In 1794, after voluntarily ceding the island Kingdom of Hawai‘i to Great Britain, Kamehameha and his chiefs considered themselves British subjects and recognized King George III as emperor. The cession to Great Britain did not radically change traditional governance, but principles of English governance and titles were instituted.

In 1795, Kamehameha conquered the Maui Kingdom, and in 1810 the Kaua‘i Kingdom became a vassal under Kamehameha through voluntary cession by its King, Kaumuali‘i. By 1840 all the Island Kingdoms were consolidated under the Hawaiian Kingdom. According to the 1840 Constitution:

The origin of the present government, and system of polity, is as follows: KAMEHAMEHA I, was the founder of the kingdom, and to him belonged all the land from one end of the Islands to the other, though it was not his own private property. It belonged to the chiefs and people in common, of whom Kamehameha I was the head, and had the management of the landed property. Wherefore, there was not formerly, and is not now any person who could or can convey away the smallest portion of land without consent of the one who had, or has the direction of the kingdom.

These are the persons who have had the direction of it from that time down, Kamehameha II, Kaahumanu I, and at the present time Kamehameha III. These persons have had the direction of the kingdom down to the present time, and all documents written by them, and no others are the documents of the kingdom.

The kingdom is permanently confirmed to Kamehameha III, and his heirs, and his heir shall be the person whom he and the chiefs shall appoint, during his life time, but should there be no appointment, then the decision shall rest with the chiefs and house of Representatives.

On June 14, 1852, a new Constitution was granted by Kamehameha III confirming the successorship of the Crown. Article 25 provides:

The crown is hereby permanently confirmed to His Majesty Kamehameha III during his life, and to his successor. The successor shall be the person whom the King and the House of Nobles shall appoint and publicly proclaim as such, during the King’s life; but should there be no such appointment and proclamation, then the successor shall be chosen by the House of Nobles and the House of Representatives in joint ballot.

Article 25 is tempered by Article 26 that states, “No person shall ever sit upon the throne who has been convicted of an infamous crime, or who is insane or an idiot. No person shall ever succeed to the crown, unless he be a descendant of the aboriginal stock of Aliʻis.” It would appear that Kamehameha III was aware of King George III’s insanity while the Hawaiian Kingdom was a British Protectorate and it no doubt informed Hawaiian governance.

Alexander Liholiho, the adopted son of the King, was confirmed by the House of Nobles as successor on April 6, 1853, in accordance with Article 25 of the 1852 Constitution. In 1854, after the death of the King, he succeeded to the throne as Kamehameha IV. Kamehameha IV was the biological son of Mataio Kekuūanaoʻa and Kīnaʻu, who was the half-sister to Kamehameha III. The confirmation process ensured that Alexander Liholiho was not “convicted of an infamous crime, or who is insane or an idiot.”

On November 30, 1863, Kamehameha IV died unexpectedly, and left the Kingdom without a successor. On the same day, the Kuhina Nui—Premier, Victoria Kamāmalu, in Privy Council, proclaimed Lot Kapuaiwa to be the successor to the throne in accordance with Article 25 of the Constitution of 1852, and the Nobles confirmed him. Lot Kapuaiwa was thereafter called Kamehameha V. Victoria Kamāmalu, as Kuhina Nui, provided continuity for the office of the Crown pending the appointment and confirmation of Lot Kapuaiwa.

Article 47, of the 1852 Constitution provided that “whenever the throne shall become vacant by reason of the King’s death the Kuhina Nui shall perform all the duties incumbent on the King, and shall have and exercise all the powers, which by this Constitution are vested in the King.” This provision prevented the House of Nobles and the House of Representives to choose a successor by joint ballot.

On August 20, 1864, Kamehameha V proclaimed the 1864 Constitution. The office of Kuhina Nui—Premier was removed and replaced by the Cabinet Council. Article 22 provided the successorship of the Hawaiian Crown:

The Crown is hereby permanently confirmed to His Majesty Kamehameha V, and to the Heirs of His body lawfully begotten, and to their lawful Descendants in a direct line; failing whom, the Crown shall descend to Her Royal Highness the Princess Victoria Kamamalu Kaahumanu, and their heirs of her body, lawfully begotten, and their lawful descendants in a direct line. The Succession shall be to the senior male child, and to the heirs of his body; failing a male child, the succession shall be to the senior female child, and the heirs of her body. In case there is no heir as above provided, then the successor shall be the person whom the Sovereign shall appoint wiht the consent of the Nobles, and publicly proclaim as such during the King’s life; but should there be no appointment and proclamation, and the Throne should become vacant, then the Cabinet Council, immediately after the occurring of such vacancy, shall cause a meeting of the Legislative Assembly, who shall elect by ballot some native Aliʻi of the Kingdom as Successor to the Throne; and the Successor so elected shall become a new Stirps for a Royal Family; and the succession from the Sovereign thus elected, shall be regulated by the same law as the present Royal Family.

The constraints upon the Crown was reiterated in Article 25, which stated, “No person shall ever sit upon the Throne, who has been convicted of any infamous crime, or who is insane, or an idiot.”

On December 11, 1872, Kamehameha V died without naming a successor to the throne. This caused the Cabinet Council to serve temporarily as a Council of Regency that serves in the absence of a Monarch. According to Article 22 of the 1864 Constitution, “the Cabinet Council, immediately after the occurring of such vacancy, shall cause a meeting of the Legislative Assembly, who shall elect by ballot some native Aliʻi of the Kingdom as Successor to the Throne.” Article 33 also provides that “the Cabinet Council at the time of such decease shall be a Council of Regency, until the Legislative Assembly, which shall be called immediately, may be assembled.”

The Lunalilo Dynasty

On January 8, 1873, the Cabinet serving as a Council of Regency convened the Legislative Assembly into Extraordinary Session. In its address to the Legislature, the Cabinet stated:

Documents delivered to your President, contain official evidence of the decease of His late Majesty Kamehameha V. His earthly existence terminated at Iolani Palace, in Honolulu, in the Island of Oahu, upon the forty-second anniversary of his birth, being the eleventh day of December, in the year of Our Lord One Thousand Eight Hundred and Seventy-two.

His Majesty left no Heirs.

Her late Royal Highness the Princess Victoria Kamamalu Kaahumanu, to whom in the event of the death of His late Majesty without heirs, the Constitution declared that the Throne should descend, died, also without heirs, on the twenty-ninth day of May, in the year of Our Lord One Thousand Eight Hundred and Sixty-six.

His late Majesty did not appoint any successor in the mode set forth in the Constitution, with the consent of the Nobles or make a Proclamation thereof during his life. There having been no such appointment or Proclamation, the Throne became vacant, and the Cabinet Council immediately thereupon considered the form of the Constitution in such case made and provided, and

Ordered—That a meeting of the Legislative Assembly be caused to be holden at the Court House in Honolulu, on Wednesday which will be the eighth day of January, A.D. 1873, at 12 o’clock noon; and of this order all Members of the Legislative Assembly will take notice and govern themselves accordingly.

By virtue of this Order you have been assembled, to elect by ballot, some native Aliʻi of this Kingdom as Successor to the Throne. Your present authority is limited to this duty, but the newly elected Sovereign may require your services after his accession.

The Members of the Cabinet Council devoutly ask the blessings of Heaven upon your deliberations and public acts. They have appreciated the responsibility resting upon them, and have striven to maintain tranquility and order, and, especially, to guard your proceedings against improper interference.

Acknowledging the obligation to preserve all the rights, honors and dignities appertaining to the Throne, and to transmit them unimpaired to a new Sovereign, it will become their duty, upon his accession, to surrender to him the authority conferred upon them by his late lamented predecessor.

The Legislative Assembly, empowered to elect a new monarch under the 1864 Constitution, elected William Charles Lunalilo on January 8, 1873. Lunalilo was not a descendant of Kamehameha I but his mother, Kekāuluohi, was the Queen Consort to Kamehameha I and Kamehameha II. His father was High Chief Charles Kana‘ina.

The Kalākaua Dynasty

The Hawaiian Kingdom’s first elected King died a year later without a named successor, and the Legislature was again convened by Lunaliloʻs Cabinet Council and elected David Kalākaua as King on February 12, 1874. On February 14, 1874, King Kalākaua appointed his younger brother, Prince William Pitt Leleiōhoku, his successor, and was confirmed by the Nobles. On April 10, 1877, Leleiōhoku died. The next day Kalākaua appointed his sister, Princess Lili‘uokalani, as heir-apparent and received confirmation from the Nobles.

When Kalākaua was elected, a new royal lineage replaced the Kamehameha and Lunalilo Dynasty. Kalākaua declared royal titles upon: Princess Lili‘uokalani, Queen Kapiʻolani, Princess Virginia Kapoʻoloku Poʻomaikelani, Princess Kinoiki, Princess Victoria Kawekiu Kaiʻulani Lunalilo Kalaninuiahilapalapa, Prince David Kawānanakoa, Prince Edward Abner Keliʻiahonui, and Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole comprised the new royal lineage. Everyone with the exception of Princess Lili‘uokalani, as heir-apparent, were heirs to the Hawaiian Throne. To move from an heir to heir-apparent is when the Monarch nominates you as successor among the other heirs, and the nominee receives confirmation from the Nobles.

When Kalākaua embarked on his world tour on January 20, 1881, Princess Lili‘uokalani served as Regent, together with the Cabinet Council. Her second time to serve as Regent with the Cabinet Council occurred when Kalākaua departed for San Francisco on November 25, 1890. Kalākaua died in San Francisco on January 20, 1891, and his body returned to Honolulu on the 29th. That day Princess Liliʻuokalani succeeded to the Throne.

The legislative and judicial branches of government had been compromised by the revolt in 1887. The Nobles became an elected body of men whose allegiance was to the foreign population, and three of the justices of the Supreme Court, including the Chief Justice, participated in the revolt by drafting the 1887 constitution. The Queen was prevented from legally confirming her niece, Victoria Kawekiu Kaiʻulani Lunalilo Kalaninuiahilapalapa, as heir-apparent, because the Nobles had not been in the Legislative Assembly since 1887. Ka‘iulani died at the age of 23 on March 6, 1899.

Up to her death on November 11, 1917, Lili‘uokalani was prevented from naming a successor to the Throne and receiving confirmation by the Nobles. The last of the Kalākaua Dynasty to die was Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole on January 7, 1922, which ended the Kalākaua Dynasty. Royal titles are not inheriteable.

The Kamehameha, Lunalilo and Kalākaua Dynasties came to a close. There are no heirs to the Throne, and the Legislative Assembly will have to be reconvened, by the Council of Regency, after the occupation comes to an end to “elect by ballot some native Aliʻi of the Kingdom as Successor to the Throne.” A “native Aliʻi” will be drawn from those who are a direct descendant of the genealogies provided by the Board of Genealogists that were published in 1896 in the Ka Maka‘ainana newspaper. To access these genealogies go to The Three Estates of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

Direct descendants of these genealogies comprise the Nobility class of the Hawaiian Kingdom and would be qualified to be elected by the Legislative Assembly after the Nobles determine that the candidate has not “been convicted of any infamous crime, or who is insane, or an idiot.”

Until such time the Council of Regency serves in the absence of the Monarch.

Reaping the Fruits of Labor – Strategic Plan of the Council of Regency

The Council of Regency, serving as the provisional government of the Hawaiian Kingdom, was established within Hawaiian territory—in situ, and not in exile. The Hawaiian government was established in accordance with the Hawaiian constitution and the doctrine of necessity to serve in the absence of the office of Executive Monarch. Queen Lili‘uokalani was the last Executive Monarch from 1891-1917.

By virtue of this process the Hawaiian government is comprised of officers de facto. According to U.S. constitutional scholar Thomas Cooley:

A provisional government is supposed to be a government de facto for the time being; a government that in some emergency is set up to preserve order; to continue the relations of the people it acts for with foreign nations until there shall be time and opportunity for the creation of a permanent government. It is not in general supposed to have any authority beyond that of a mere temporary nature resulting from some great necessity, and its authority is limited to the necessity.

During the Second World War, like other governments formed during foreign occupations of their territory, the Hawaiian government did not receive its mandate from the Hawaiian legislature, but rather by virtue of Hawaiian constitutional law as it applies to the Cabinet Council, which is comprised of the constitutional offices of the Minister of Interior, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Minister of Finance and the Attorney General.

Although Article 33 of the 1864 Constitution, as amended, provides that the Cabinet Council “shall be a Council of Regency, until the Legislative Assembly, which shall be called immediately [and] shall proceed to choose by ballot, a Regent or Council of Regency, who shall administer the Government in the name of the King, and exercise all the Powers which are constitutionally vested in the King,” the convening of the Legislative Assembly was not possible in light of the prolonged occupation. The impossibility of convening the Legislative Assembly during the occupation did not prevent the Cabinet from becoming the Council of Regency because of the operative words “shall be a Council of Regency, until…,” but only prevents, for the time being of occupation, the Legislature from electing a Regency or Regency. That election will take place when the occupation comes to an end.

Therefore, the Council was established in similar fashion to the Belgian Council of Regency after King Leopold was captured by the Germans during the Second World War. As the Belgian Council was established under Article 82 of its 1821 Constitution, as amended, in exile, the Hawaiian Council was established under Article 33 of its 1864 Constitution, as amended, not in exile but rather in situ. As Professor Oppenheim explained:

As far as Belgium is concerned, the capture of the king did not create any serious constitutional problems. According to Article 82 of the Constitution of February 7, 1821, as amended, the cabinet of ministers have to assume supreme executive power if the King is unable to govern. True, the ministers are bound to convene the House of Representatives and the Senate and to leave it to the decision of the united legislative chambers to provide for a regency; but in view of the belligerent occupation it is impossible for the two houses to function. While this emergency obtains, the powers of the King are vested in the Belgian Prime Minister and the other members of the cabinet.

The existence of the restored government in situ was not dependent upon diplomatic recognition by foreign States, but rather operated on the presumption of recognition these foreign States already afforded to the Hawaiian government as of 1893.

The recognition of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State on November 28, 1843, was also the recognition of its government—a constitutional monarchy, as its agent. Successors in office to King Kamehameha III, who at the time of international recognition was King of the Hawaiian Kingdom, did not require diplomatic recognition. These successors included King Kamehameha IV in 1854, King Kamehameha V in 1863, King Lunalilo in 1873, King Kalākaua in 1874, and Queen Lili‘uokalani in 1891. The legal doctrines of recognition of new governments only arise “with extra-legal changes in government” of an existing State. Successors to King Kamehameha III were not established through “extra-legal changes,” but rather under the constitution and laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom. According to Professor Peterson:

A government succeeding to power according to the constitution, basic law, or established domestic custom is assumed to succeed as well to its predecessor’s status as international agent of the state. Only if there is legal discontinuity at the domestic level because a new government comes to power in some other way, as by coup d’état or revolution, is its status as an international agent of the state open to question.

The Hawaiian Council of Regency is a government restored in accordance with the constitutional laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom as they existed prior to the unlawful overthrow of the previous administration of Queen Lili‘uokalani. It was not established through “extra-legal changes,” and, therefore, did not require diplomatic recognition to give itself validity as a government. It was a successor in office to Queen Lili‘uokalani as the Executive Monarch.

According to Professor Lenzerini in his legal opinion, based on the doctrine of necessity, “the Council of Regency possesses the constitutional authority to temporarily exercise the Royal powers of the Hawaiian Kingdom.” He also concluded that the Regency “has the authority to represent the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State, which has been under a belligerent occupation by the United States of America since 17 January 1893, both at the domestic and international level.”

After all four offices of the Cabinet Council were filled on September 26, 1999, a strategic plan was adopted based on its policy: first, exposure of the prolonged occupation; second, ensure that the United States complies with international humanitarian law; and, third, prepare for an effective transition to a completely functioning government when the occupation comes to end. The Council of Regency’s strategic plan has three phases to carry out its policy.

Phase I: Verification of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State and subject of International Law

Phase II: Exposure of Hawaiian Statehood within the framework of international law and the laws of occupation as it affects the realm of politics and economics at both the international and domestic levels.

Phase III: Restoration of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State and a subject of International Law, which is when the occupation comes to an end.

This Grand Strategy of the Council of Regency is long term, not short term, and can be compared to China’s Grand Strategy, which is also long term. As Professors Flynt Leverett and Wu Bingbing explain in their article The New Silk Road and China’s Evolving Grand Strategy:

What is grand strategy, and what does it mean for China? In broad terms, grand strategy is the culturally shaped intellectual architecture that structures a nation’s foreign policy over time. It is, in Barry Posen’s aphoristic rendering, “a state’s theory of how it can best ‘cause’ security for itself.” Put more functionally, grand strategy is a given political order’s template for marshalling all elements of national power to achieve its self-defined long-term goals. Diplomacy—a state’s capacity to increase the number of states ready to cooperate with it and to decrease its actual and potential adversaries—is as essential to grand strategy as raw military might. So too is economic power. For any state, the most basic goal of grand strategy is to protect that state’s territorial and political integrity. Beyond this, the grand strategies of important states typically aim to improve their relative positions by enhancing their ability to shape strategic outcomes, maximize their influence, and bolster their long-term economic prospect.

Phase I was completed when the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) acknowledged the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State for the purposes of its institutional jurisdiction under Article 47 of the 1907 Hague Convention, I, for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes prior to forming the arbitration tribunal on June 9, 2000. This acknowledgment of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State can be found at its case repository for Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom and on its website. The non-participation of the United States in the arbitration proceedings occurred “after” the PCA already acknowledged the continued existence of Hawaiian Kingdom Statehood.

On the day when the arbitration tribunal was formed, Phase II was initiated—exposure. Phase II would be guided by Section 495—Remedies of Injured Belligerent, United States Army FM 27-10, which states, “In the event of violation of the law of war, the injured party may legally resort to remedial action of…Publication of the facts, with a view to influencing public opinion against the offending belligerent.” The exposure began with the filings of the Hawaiian Kingdom in the arbitration proceedings and its oral arguments on December 8 and 11, 2000, at the PCA, in The Hague, Netherlands, which can be seen in this mini-documentary of the proceedings.

After the last day of the Larsen hearings were held at the PCA on December 11, 2000, the Council was called to an urgent meeting by Dr. Jacques Bihozagara, Ambassador for the Republic of Rwanda assigned to Belgium. Ambassador Bihozagara had been attending a hearing before the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on December 8, Democratic Republic of the Congo v. Belgium, where he became aware of the Hawaiian arbitration case taking place in the hearing room of the PCA across the hall of the Peace Palace. Both the PCA and the ICJ are housed in the same building.

The following day, the Council, which included David Keanu Sai, acting Minister of Interior and Chairman of the Council of Regency, as Agent, and two Deputy Agents, Peter Umialiloa Sai, acting Minister of Foreign Affairs, and Mrs. Kau‘i P. Sai-Dudoit, formerly known as Kau‘i P. Goodhue, acting Minister of Finance, met with Ambassador Bihozagara in Brussels. In that meeting, the Ambassador explained that since he accessed the pleadings and records of the Larsen case on December 8 from the PCA’s Secretariat, he had been in communication with his government in Kigali. This prompted our meeting where the Ambassador conveyed to the Council that his government was prepared to bring to the attention of the United Nations General Assembly the prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom by the United States and to place our situation on the agenda. The Council requested a short break from the meeting to discuss this offer.

After careful deliberation, the Council of Regency decided that it could not, in good conscience, accept this offer. The Council felt that the timing was premature because Hawai‘i’s population remained ignorant of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s profound legal position due to institutionalized denationalization through Americanization by the United States for over a century. The Council graciously thanked the Ambassador for his government’s offer but stated that the Council first needed to address over a century of denationalization. After exchanging salutations, the meeting ended, and the Council returned that afternoon to The Hague. The meeting also constituted recognition of the restored government.

Since the Council of Regency returned home from the Netherlands, it was agreed that David Keanu Sai would enter the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa to pursue a Masters Degree in Political Science, specializing in international relations and law, and then a Ph.D. Degree in Political Science with particular focus on the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State. Dr. Sai is currently a Lecturer in Political Science and Hawaiian Studies at the University of Hawai‘i Windward Community College and Affiliate Faculty of the Graduate Division of the University of Hawai‘i College of Education.

Kau‘i Sai-Dudoit would work for the Hawaiian newspaper project and she is currently Programs Director for Awaiaulu, Inc. Awaiaulu is dedicated to developing resources and resource people that can bridge Hawaiian knowledge from the past to the present and the future. Historical resources are made accessible so as to build the knowledge base of both Hawaiian and English-speaking audiences, and young scholars are trained to understand and interpret those resources for modern audiences today and tomorrow.

Since Phase II of Exposure began:

- Multiple Master’s theses, Ph.D. dissertations, published articles and books address different subjects in the Hawaiian Kingdom as an occupied State.

- Classes are now being taught here and abroad on the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom and its prolonged occupation by the United States.

- On July 12, 2002, Professor Matthew Craven author’s Legal Opinion on the Continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State under International Law.

- 2011, Dr. Keanu Sai author’s book Ua Mau Ke Ea – Sovereignty Endures: An Overview of the Political and Legal History of the Hawaiian Islands.

- The Hawai‘i State Teachers Association, representing public school teachers throughout Hawai‘i, introduced a resolution at the National Education Association’s (NEA) annual assembly in Boston, Massachusetts, which passed on July 4, 2017, that called upon the NEA to publish articles on the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Monarchy in 1893, the prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom by the United States, and the harmful affects the occupation has had on the Hawaiian people and the resources of the land.

- On April 2, 2018, the NEA published the online article The Illegal Overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom Government.

- On October 1, 2018, the NEA published the online article The U.S. Occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

- On October 13, 2018, the NEA published the online article The Impact of the U.S. Occupation on the Hawaiian People.

- Attorneys continue to make legal arguments on the Hawaiian Kingdom’s existence in criminal and civil proceedings in State of Hawai‘i Courts.

- On February 25, 2018, Dr. Alfred deZayas, as the United Nations Independent Expert for the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva, Switzerland, sent a letter of communication to the State of Hawai‘i Judiciary regarding the prolonged occupation.

- On June 25, 2018, the Hawaiian Kingdom filed a Petition for Writ of Mandamus against President Donald Trump in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia in Washington, D.C.

- On July 25, 2019, Professor William Schabas author’s a Legal Opinion on War Crimes Related to the United States Occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom since 17 January 1893.

- On October 4, 2019, Professor Federico Lenzerini author’s Legal Opinion—International Human Rights Law and Self-Determination of Peoples Related to the United States Occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom since 17 January 1893.

- After the National Lawyers Guild’s (NLG) membership passed a resolution in December of 2019, the National Office took an official position on January 13, 2020, Calling Upon US to Immediately Comply with International Humanitarian Law in its Illegal Occupation of the Hawaiian Islands.

- 2020 Dr. Keanu Sai (ed.) author’s Royal Commission of Inquiry: Investigating War Crimes and Human Rights Violations in the Hawaiian Kingdom, with contributing authors: Professor Matthew Craven, Professor William Schabas and Professor Federico Lenzerini.

- On November 10, 2020, the NLG sent a letter of communication to State of Hawai‘i Governor urging him to comply with international humanitarian law by transforming the State of Hawai‘i into an occupying government in order to administer Hawaiian Kingdom law and the law of occupation.

- On May 24, 2020, Professor Federico Lenzerini author’s a Legal Opinion on the Authority of the Council of Regency of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

- On February 7, 2021, the International Association of Democratic Lawyers (IADL) passed a resolution calling upon the United States to begin to comply with international humanitarian law in its prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

- On May 20, 2021, the Hawaiian Kingdom filed a Complaint against President Biden and other officials of the Federal Government and the State of Hawai‘i, which included 30 foreign Consulates operating in the Hawaiian Islands, Hawaiian Kingdom v. Biden et al., in the United States District Court for the District of Hawai‘i.

- On July 18, 2021, the General Synod of the United Church of Christ passed a resolution submitted by the Association of Hawaiian Evangelical Churches (AHEC), Encouraging to End 128 years of of War between the United States of America and the Hawaiian Kingdom.

- On August 11, 2021, the Hawaiian Kingdom filed an Amended Complaint in the United States District Court for the District of Hawai‘i by removing the Counties of the State of Hawai‘i as Defendants.

- After receiving permission from the Court in Hawaiian Kingdom v. Biden, on September 30, 2021, the IADL, the NLG and the Water Protector Legal Collective filed an Amicus Brief on the status of the Court as an Article II Occupation Court on October 6, 2021.

- On February 16, 2022, the IADL and the American Association of Jurists—Asociación Americana de Juristas (AAJ), both of whom have consultative status with the United Nations Human Rights Council, sent a joint letter to all United Nations Ambassadors calling for enforcement of international law regarding the prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

- The NLG, the IADL, the AAJ and AHEC support the Council of Regency and its strategy to bring the United States and the State of Hawai‘i and its Counties in compliance with international humanitarian law and the law of occupation.

- On February 23, 2022, AHEC sent a letter of communication to State of Hawai‘i Governor supporting the letter sent by the NLG on November 10, 2020, calling upon the State of Hawai‘i to transform into an Occupying Government.