Incredible as it may sound, the United States committed an act of war of aggression against the Hawaiian Kingdom, being a neutral State, when it was at war with Spain in 1898, and that the United States has been in a war of aggression against Hawai‘i ever since. This war of aggression has lasted over 116 years, the longest ever since the Thirty Years War (1618-1648). According to Oppenheim’s International Law (7th ed.), p. 685, “hostilities against a neutral [State] on the part of either belligerent are acts of war, and not mere violations of neutrality. Thus the German attack on Belgium in 1914, to enable German troops to march through Belgian territory and attack France, created war between Germany and Belgium.”

The United States intent and purpose was to deliberately violate the neutrality of the Hawaiian Kingdom in order to fight Spain in its colonies of Guam and the Philippines, and after the war to use the Hawaiian Islands as a military outpost to protect the west coast of the United States as well as a base of operations for future wars. The action taken by the United States draws parallels to Germany’s occupation of neutral States during World War I and II, which at the time was thought of as unprecedented, but it wasn’t. The United States set the precedent in 1898.

On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded and occupied the neutral territories of Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg in order to fight France and Great Britain during World War II. The Nuremburg Tribunal concluded in its Nuremburg Judgment, that these invasions and subsequent occupations were unjustified acts of an aggressive war. The Tribunal stated:

“There is no evidence before the Tribunal to justify the contention that the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg were invaded by Germany because their occupation had been planned by England and France. British and French staffs had been operating in the Low Countries, but the purpose of this planning was to defend these countries in the event of a German attack.”

“The invasion of Belgium, Holland and Luxembourg was entirely without justification.”

“It was carried out in pursuance of policies long considered and prepared, and was plainly an act of aggressive war. The resolve to invade was made without any other consideration than the advancement of the aggressive policies of Germany.”

Of the three neutral States, the situation with Luxembourg bears the closest similarity to the Hawaiian Kingdom, whereby Germany also unilaterally annexed Luxembourg and initiated an aggressive campaign of “Germanization” and “Nazification” in the public schools. The United States also initiated an aggressive campaign of “Americanization” in the public schools that sought to obliterate the national character of the Hawaiian Kingdom and replace it with American patriotism.

Luxembourg was previously occupied by Germany for the same unjustified reasons from 1914-1918 during World War I.

The Hawaiian Kingdom also has Treaties of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation, with all three countries: Belgium (October 4, 1862), and the Netherlands and Luxembourg (October 16, 1862). William III, King of the Netherlands, who entered into the Dutch treaty, was also the Grand Duke of Luxembourg.

War, under international law, is considered an extension of a State’s sovereignty and therefore regulated by the laws of war as opposed to the laws of peace. International law separates the rights of belligerent States from the rights of neutral States. Laws of war—jus in bello, make up a part of customary international law until declared in law making treaties that began in the mid-nineteenth century. The first treaty was the 1856 Paris Declaration Respecting Maritime Law that abolished privateering, which later progressed to the 1899 and 1907 Hague Conventions, and the 1949 Geneva Conventions. In order for the laws of peace to return, war must come to an end. If not, then the laws of war—jus in bello, remain over the regions that are affected by the war itself. For the case of neutral States being illegally occupied during a war, being an act of war of aggression, its state of war with the belligerent occupant will continue until the occupying State ceases to occupy the neutral State, and the laws of war would still apply according to the 1907 Hague Convention, IV, and the 1949 Geneva Convention, IV.

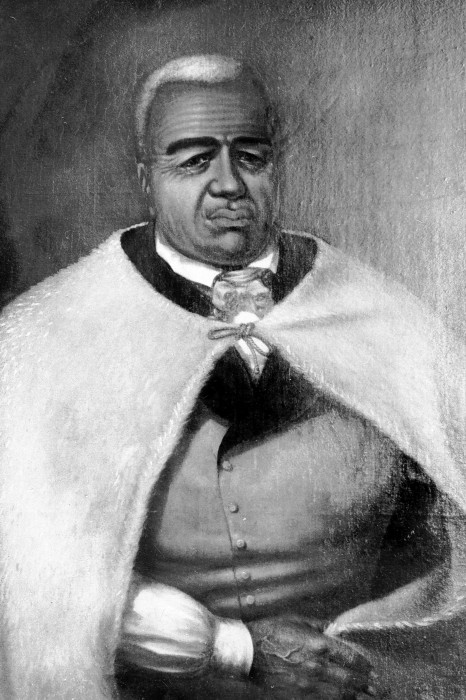

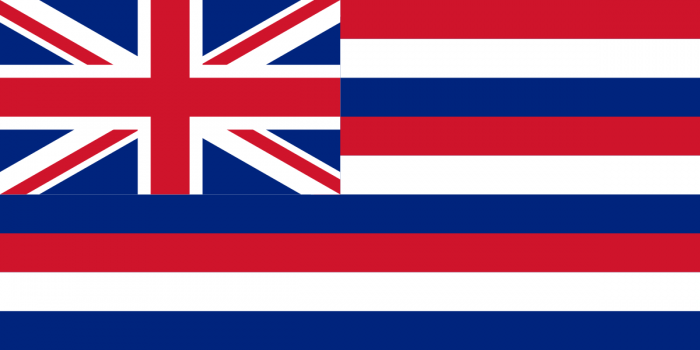

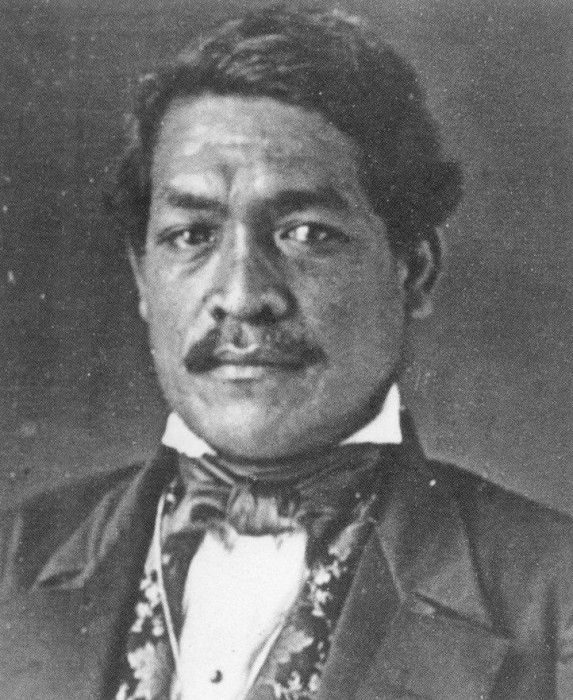

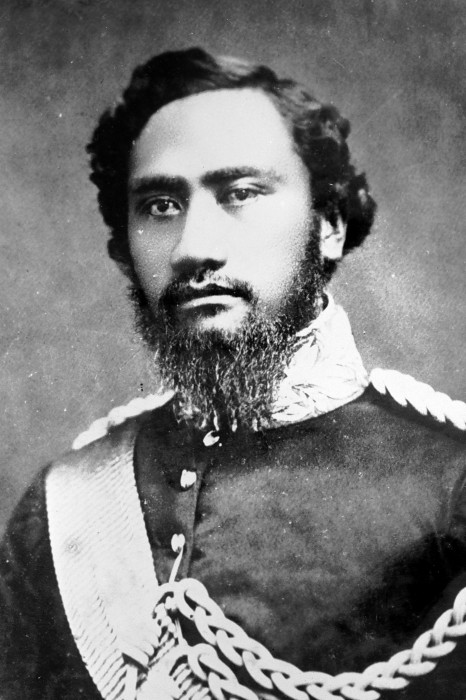

Hawaiian neutrality began with King Kamehameha III’s proclamation of neutrality during the Crimean War on May 16, 1854. Since then, the Hawaiian government worked with other Powers, to include the United States, to have Hawai‘i’s neutrality respected in all subsequent wars. Neutrality provisions were inserted in the treaties with Sweden/Norway, Spain, Germany, and Italy.

Hawaiian neutrality began with King Kamehameha III’s proclamation of neutrality during the Crimean War on May 16, 1854. Since then, the Hawaiian government worked with other Powers, to include the United States, to have Hawai‘i’s neutrality respected in all subsequent wars. Neutrality provisions were inserted in the treaties with Sweden/Norway, Spain, Germany, and Italy.

On April 7, 1855, His Majesty King Kamehameha IV opened the Legislative Assembly, and in his speech he reiterated the Kingdom’s neutrality.

“It is gratifying to me, on commencing my reign, to be able to inform you, that my relations with all the great Powers, between whom and myself exist treaties of amity, are of the most satisfactory nature. I have received from all of them, assurances that leave no room to doubt that my rights and sovereignty will be respected. My policy, as regards all foreign nations, being that of peace, impartiality and neutrality, in the spirit of the Proclamation by the late King, of the 16th May last, and of the Resolutions of the Privy Council of the 15th June and 17th July. I have given to the President of the United States, at his request, my solemn adhesion to the rule, and to the principles establishing the rights of neutrals during war, contained in the Convention between his Majesty the Emperor of all the Russias, and the United States, concluded in Washington on the 22nd July last.”

“It is gratifying to me, on commencing my reign, to be able to inform you, that my relations with all the great Powers, between whom and myself exist treaties of amity, are of the most satisfactory nature. I have received from all of them, assurances that leave no room to doubt that my rights and sovereignty will be respected. My policy, as regards all foreign nations, being that of peace, impartiality and neutrality, in the spirit of the Proclamation by the late King, of the 16th May last, and of the Resolutions of the Privy Council of the 15th June and 17th July. I have given to the President of the United States, at his request, my solemn adhesion to the rule, and to the principles establishing the rights of neutrals during war, contained in the Convention between his Majesty the Emperor of all the Russias, and the United States, concluded in Washington on the 22nd July last.”

The aforementioned Declarations and the 1854 Russian-American Convention represented the first recognition of the right of neutral States to conduct free trade without any hindrance from war. Stricter guidelines for neutrality were later established in the 1871 Treaty of Washington between the United States and Great Britain that was negotiated during the aftermath of the American Civil War, which also formed the basis of the Alabama claims arbitration in Geneva, Switzerland.

Without justification, the United States of America is directly responsible for the violation of the neutrality of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the occupation of its territory for military purposes during the 1898 Spanish-American War. Article XXVI of the Hawaiian-Spanish Treaty of October 29, 1863, provides, “All vessels bearing the flag of Spain, shall, in time of war, receive every possible protection, short of active hostility, within the ports and waters of the Hawaiian Islands, and Her Majesty the Queen of Spain engages to respect, in time of war the neutrality of the Hawaiian Islands, and to use her good offices with all the other powers having treaties with the same, to induce them to adopt the same policy toward the said Islands.”

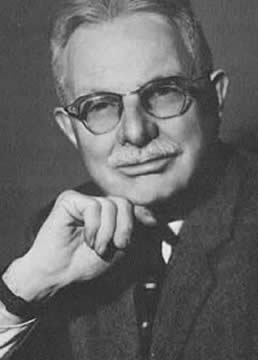

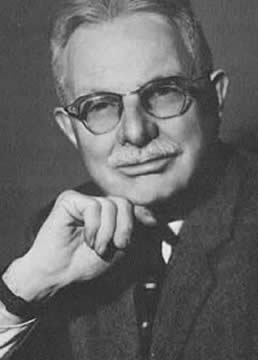

According to the well-known American publicist on international law, Quincy Wright’s A Study of War, 2nd ed., p. 787, “The status of neutrality reached its climax in the nineteenth century with the especial support of Great Britain and the United States.” According to Wright, the rules of neutral status “were to a considerable extent codified in the American Neutrality act (1794), the British Foreign Enlistment Act (1819), the Declaration of Paris (1856), the rules of the Treaty of Washington (1871), the Hague Conventions (1907), and the Declaration of London (1909).”

According to the well-known American publicist on international law, Quincy Wright’s A Study of War, 2nd ed., p. 787, “The status of neutrality reached its climax in the nineteenth century with the especial support of Great Britain and the United States.” According to Wright, the rules of neutral status “were to a considerable extent codified in the American Neutrality act (1794), the British Foreign Enlistment Act (1819), the Declaration of Paris (1856), the rules of the Treaty of Washington (1871), the Hague Conventions (1907), and the Declaration of London (1909).”

Article VI of the 1871 Treaty of Paris between the United States and Great Britain declared that a neutral government is bound “Not to permit or suffer either belligerent to make use of its ports or waters as the base of naval operations against the other, or for the purpose of renewal or augmentation of military supplies or arms, or the recruitment of men.” The United States regarded this rule as declaratory of existing customary international law of the time. This rule was reproduced in Articles 1, 2 and 4 of the 1907 Hague Convention, V, which contained these provisions—“The territory of neutral Powers is inviolable” (Article 1); “Belligerents are forbidden to move troops or convoys, whether of munitions of war or of supplies, across the territory of a neutral Power” (Article 2); “Corps of combatants cannot be formed nor recruiting agencies opened on the territory of a neutral Power to assist the belligerents” (Article 4).

There is no doubt of the binding force of the 1863 Hawaiian-Spanish Treaty, the 1871 Treaty of Washington, and customary international law, as well as assurances by the United States through diplomatic notes since 1854, which guaranteed the neutrality of the Hawaiian Islands during the Spanish-American War.

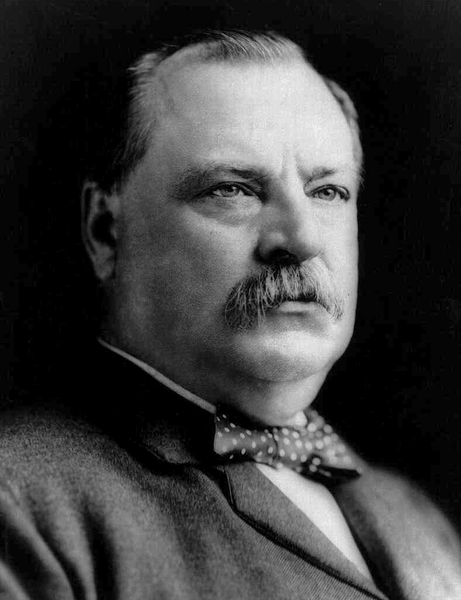

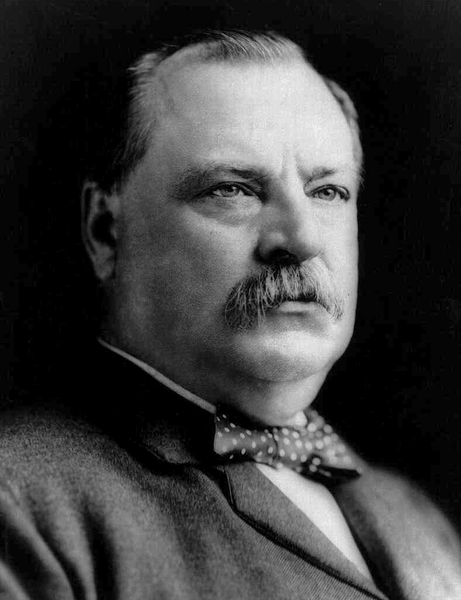

On December 18, 1893, an executive agreement was reached through exchange of diplomatic notes between United States President Grover Cleveland and the Hawaiian Kingdom’s Queen Lili‘uokalani, whereby the United States committed to the reinstatement of the constitutional government, and thereafter the Queen to grant a full pardon to a minority of insurgents who participated with the United States Legation in the unlawful overthrow of the Hawaiian government. Prior to the agreement, the United States initiated a presidential investigation on April 1, 1893 after ordering U.S. troops to return to the U.S.S. Boston that was anchored in Honolulu harbor. The investigation was concluded on October 18, 1893 and concluded that the United States was entirely responsible for the unlawful overthrow of the Hawaiian government by its military force.

On December 18, 1893, an executive agreement was reached through exchange of diplomatic notes between United States President Grover Cleveland and the Hawaiian Kingdom’s Queen Lili‘uokalani, whereby the United States committed to the reinstatement of the constitutional government, and thereafter the Queen to grant a full pardon to a minority of insurgents who participated with the United States Legation in the unlawful overthrow of the Hawaiian government. Prior to the agreement, the United States initiated a presidential investigation on April 1, 1893 after ordering U.S. troops to return to the U.S.S. Boston that was anchored in Honolulu harbor. The investigation was concluded on October 18, 1893 and concluded that the United States was entirely responsible for the unlawful overthrow of the Hawaiian government by its military force.

President Cleveland declared in his message to Congress on December 18, 1893, “And so it happened that on the 16th day of January, 1893, between four and five o’clock in the afternoon, a detachment of marines from the United States steamer Boston, with two pieces of artillery, landed at Honolulu. The men, upwards of 160 in all, were supplied with double cartridge belts filled with ammunition and with haversacks and canteens, and were accompanied by a hospital corps with stretchers and medical supplies. This military demonstration upon the soil of Honolulu was of itself an act of war, unless made either with the consent of the Government of Hawaii or for the bona fide purpose of protecting the imperiled lives and property of citizens of the United States. But there is no pretense of any such consent on the part of the Government of the Queen, which at that time was undisputed and was both the de facto and the de jure government.” Cleveland also concluded that the provisional government that seized control of the constitutional government with U.S. troops, “was neither a government de facto nor de jure,” but self-declared.

President Cleveland declared in his message to Congress on December 18, 1893, “And so it happened that on the 16th day of January, 1893, between four and five o’clock in the afternoon, a detachment of marines from the United States steamer Boston, with two pieces of artillery, landed at Honolulu. The men, upwards of 160 in all, were supplied with double cartridge belts filled with ammunition and with haversacks and canteens, and were accompanied by a hospital corps with stretchers and medical supplies. This military demonstration upon the soil of Honolulu was of itself an act of war, unless made either with the consent of the Government of Hawaii or for the bona fide purpose of protecting the imperiled lives and property of citizens of the United States. But there is no pretense of any such consent on the part of the Government of the Queen, which at that time was undisputed and was both the de facto and the de jure government.” Cleveland also concluded that the provisional government that seized control of the constitutional government with U.S. troops, “was neither a government de facto nor de jure,” but self-declared.

After President Cleveland submitted a request to Congress for authorization to use force in order to reinstate the constitutional government of the Queen, which had been usurped by the United States, the House of Representatives and the Senate each passed resolutions calling upon the President to not carry out the executive agreements and also issued warnings to foreign States to not intervene in the Hawaiian situation.

U.S. Senate resolution, May 31, 1894, 53 Cong., 2nd Sess., 5499 (1894):

“Resolved, That of right it belongs wholly to the people of the Hawaiian Islands to establish and maintain their own form of government and domestic polity; that the United States ought in nowise to interfere therewith, and that any intervention in the political affairs of these islands by any other government will be regarded as an act unfriendly to the United States.”

U.S. House resolution, February 7, 1894, 53 Cong., 2nd Sess., 2000 (1894):

“Resolved, First. That it is the sense of this House that the action of the United States minister in employing United States naval forces and illegally aiding in overthrowing the constitutional Government of the Hawaiian Islands in January, 1893, and in setting up in its place a Provisional Government not republican in form and in opposition to the will of a majority of the people, was contrary to the traditions of our Republic and the spirit of our Constitution, and should be condemned. Second. That we heartily approve the principle announced by the President of the United States that interference with the domestic affairs of an independent nation is contrary to the spirit of American institutions. And it is further the sense of this House that the annexation of the Hawaiian Islands to our country, or the assumption of a protectorate over them by our Government is uncalled for and inexpedient; that the people of that country should have their own line of policy, and that foreign intervention in the political affairs of the islands will not be regarded with indifference by the Government of the United States.”

Without Congressional support, the President could not deploy U.S. troops back to Hawai‘i in order to reinstate the constitutional government and the insurgents hired mercenaries from the United States to fill the vacuum left by the departure of U.S. troops. On July 4, 1894, the insurgency was renamed the Republic of Hawai‘i, which Congress over one hundred years later in its apology for the 1893 overthrow the Hawaiian Kingdom government, U.S. Public Law 103-150, admitted was “self-declared.”

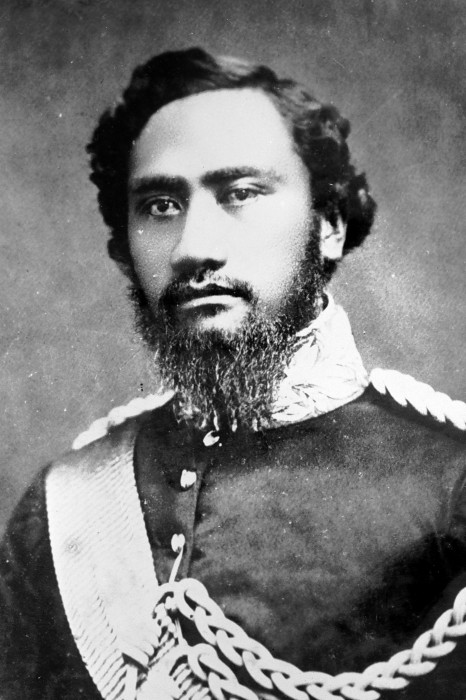

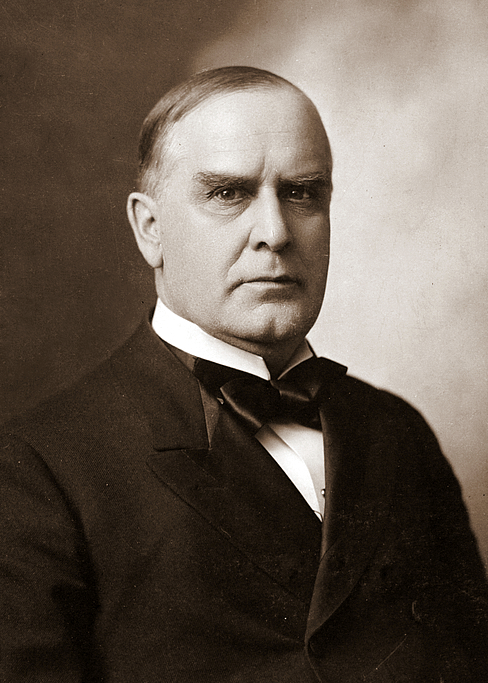

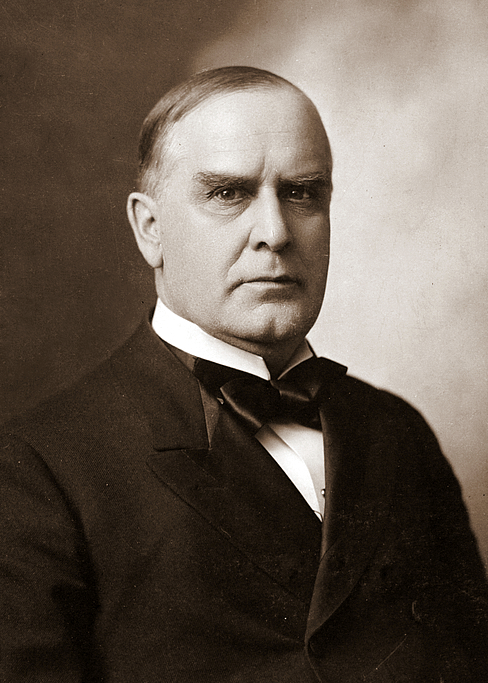

The insurgents were desperately holding on to power until a new President entered office so that the original plan of annexation could be completed. On March 4, 1897, President William McKinley entered office and another attempt to annex by treaty failed as a result of protests by Queen Lili‘uokalani and by the people.

The insurgents were desperately holding on to power until a new President entered office so that the original plan of annexation could be completed. On March 4, 1897, President William McKinley entered office and another attempt to annex by treaty failed as a result of protests by Queen Lili‘uokalani and by the people.

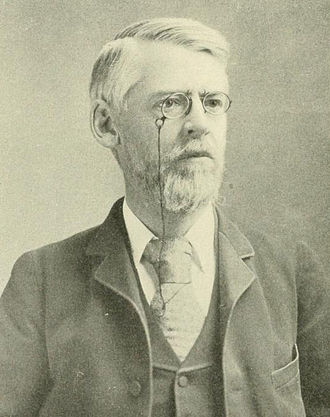

On April 25, 1898, Congress declared war on Spain. Battles were fought in the Spanish colonies of Puerto Rico and Cuba, as well as the Spanish colonies of the Philippines and Guam. After Commodore Dewey defeated the Spanish Fleet in the Philippines on May 1, 1898, U.S. Representative Francis Newlands, submitted House joint resolution no. 259 for the annexation of the Hawaiian Islands to the House Committee on Foreign Affairs on May 4, 1898. Six days later, hearings were held on the Newlands resolution, and in testimony submitted to the committee, U.S. military leaders called for the immediate violation of Hawaiian neutrality and occupation of the Hawaiian Islands due to military necessity for both during the war with Spain and for any future wars that the United States would enter.

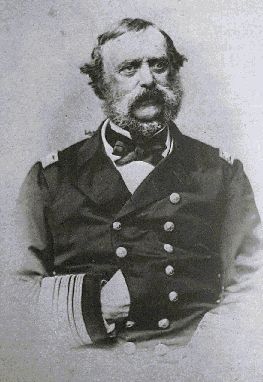

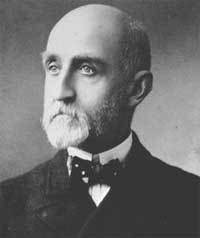

U.S. Naval Captain Alfred Mahan stated to the committee: “It is obvious that if we do not hold the islands ourselves we cannot expect the neutrals in the war to prevent the other  belligerent from occupying them; nor can the inhabitants themselves prevent such occupation. The commercial value is not great enough to provoke neutral interposition. In short, in war we should need a larger Navy to defend the Pacific coast, because we should have not only to defend our own coast, but to prevent, by naval force, an enemy from occupying the islands; whereas, if we preoccupied them, fortifications could preserve them to us. In my opinion it is not practicable for any trans-Pacific country to invade our Pacific coast without occupying Hawaii as a base.”

belligerent from occupying them; nor can the inhabitants themselves prevent such occupation. The commercial value is not great enough to provoke neutral interposition. In short, in war we should need a larger Navy to defend the Pacific coast, because we should have not only to defend our own coast, but to prevent, by naval force, an enemy from occupying the islands; whereas, if we preoccupied them, fortifications could preserve them to us. In my opinion it is not practicable for any trans-Pacific country to invade our Pacific coast without occupying Hawaii as a base.”

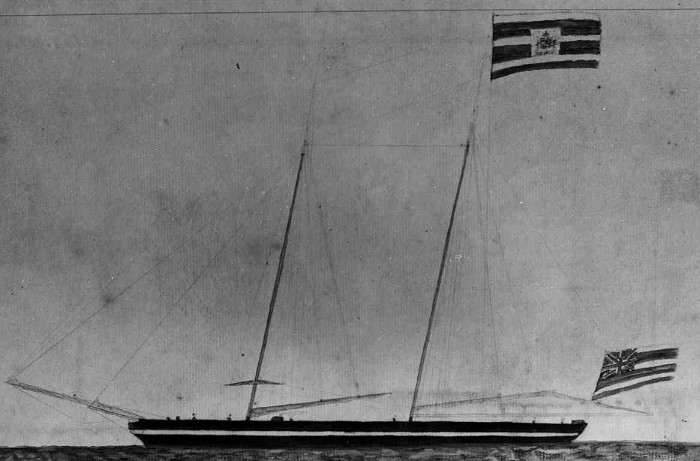

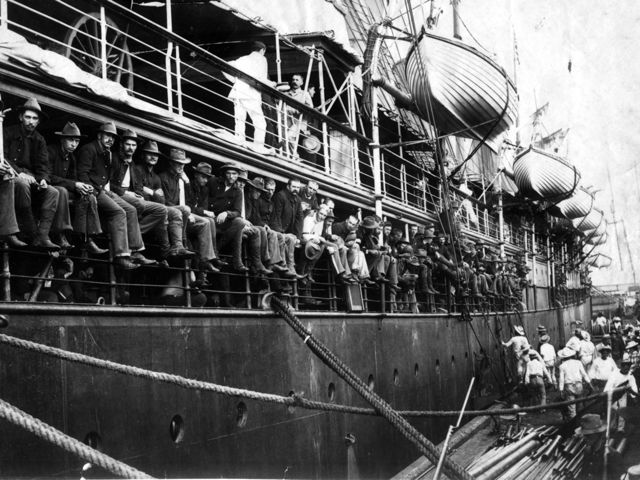

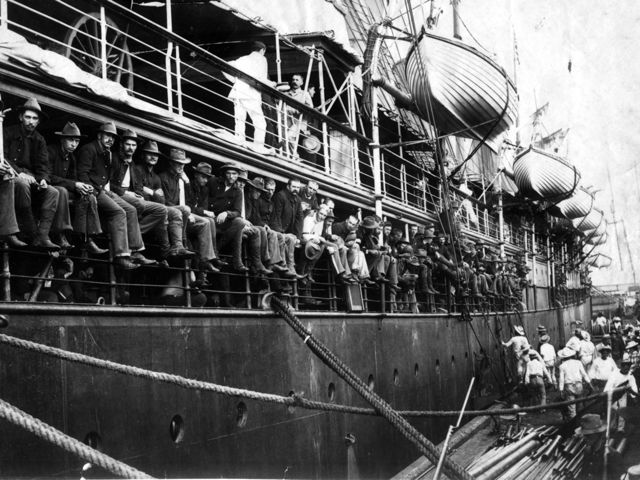

While the debates ensued in both the U.S. House and Senate, the U.S.S. Charleston, a protected cruiser, was ordered to lead a convoy of 2,500 troops to reinforce U.S. troops in the Philippines and Guam. These troops were boarded on the transport ships of the City of Peking, the City of Sidney and the Australia. In a deliberate violation of Hawaiian neutrality during the war as well as of international law, the convoy, on May 21, set a course to the Hawaiian Islands for re-coaling purposes. The convoy arrived in Honolulu on June 1, and took on 1,943 tons of coal before it left the islands on June 4.

As soon as it became apparent that the self-declared Republic of Hawai‘i, a puppet regime of the United States since 1893, had welcomed the U.S. naval convoys and assisted in re-coaling their ships, H. Renjes, Spanish Vice-Consul in Honolulu, lodged a formal protest on June 1, 1898. Minister Harold Sewall, from the U.S. Legation in Honolulu, notified Secretary of State William R. Day of the Spanish protest in a dispatch dated June 8. Renjes declared, “In my capacity as Vice Consul for Spain, I have the honor today to enter a formal protest with the Hawaiian Government against the constant violations of Neutrality in this harbor, while actual war exists between Spain and the United States of America.” A second convoy of troops bound for the Philippines, on the transport ships the China, Zelandia, Colon, and the Senator, arrived in Honolulu on June 23, and took on 1,667 tons of coal.

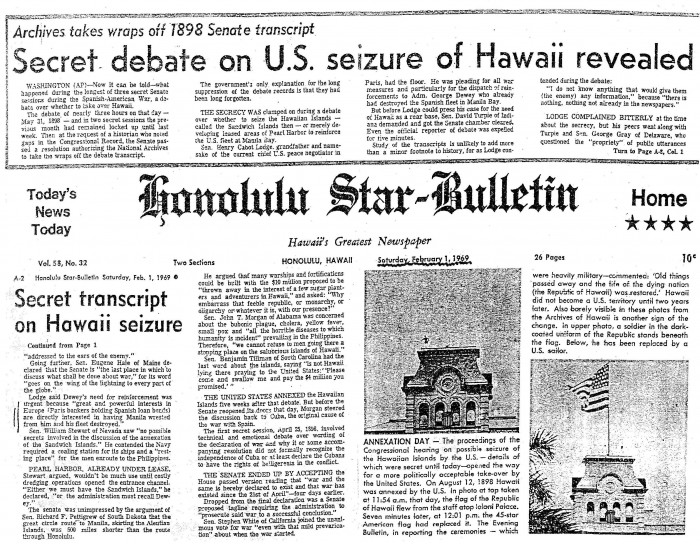

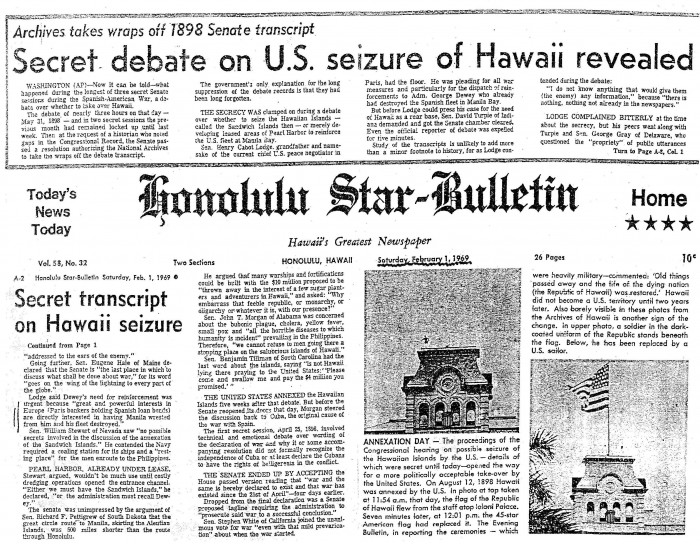

In a secret session of the U.S. Senate on May 31, 1898, Senator William Chandler warned of the consequences Alabama claims arbitration in Geneva, whereby Great Britain was found guilty of violating its neutrality during the American Civil War and compensated the United States with 15.5 million dollars in gold. Chandler cautioned, p. 278 of the secret session transcripts, “What I said was that if we destroyed the neutrality of Hawai‘i Spain would have a claim against Hawai‘i which she could enforce according to the principles of the Geneva Award and make Hawai‘i, if she were able to do it, pay for every dollar’s worth of damage done to the ships of property of Spain by the fleet that may go out of Hawai‘i.”

In a secret session of the U.S. Senate on May 31, 1898, Senator William Chandler warned of the consequences Alabama claims arbitration in Geneva, whereby Great Britain was found guilty of violating its neutrality during the American Civil War and compensated the United States with 15.5 million dollars in gold. Chandler cautioned, p. 278 of the secret session transcripts, “What I said was that if we destroyed the neutrality of Hawai‘i Spain would have a claim against Hawai‘i which she could enforce according to the principles of the Geneva Award and make Hawai‘i, if she were able to do it, pay for every dollar’s worth of damage done to the ships of property of Spain by the fleet that may go out of Hawai‘i.”

He later poignantly asked Senator Stephen White (p. 279), “whether he is willing to have the Navy and Army of the U.S. violate the neutrality of Hawai‘i?” White responded, “I am not, as everybody knows, a soldier, nor am I familiar with military affairs, but if I were conducting this Govt. and fighting Spain I would proceed so far as Spain was concerned just as I saw fit.”

Senator Henry Cabot Lodge answered Senator White’s question directly (p. 280). “I should have argued then what has been argued ably since we came into secret legislative session, that at this moment the Administration was compelled to violate the neutrality of those islands, that protests from foreign representatives had already been received and complications with other powers were threatened, that the annexation or some action in regard to those islands had become a military necessity.”

Senator Henry Cabot Lodge answered Senator White’s question directly (p. 280). “I should have argued then what has been argued ably since we came into secret legislative session, that at this moment the Administration was compelled to violate the neutrality of those islands, that protests from foreign representatives had already been received and complications with other powers were threatened, that the annexation or some action in regard to those islands had become a military necessity.”

The transcripts of the Senate’s secret session were not made public until 1969.

Commenting on the United States flagrant violation of Hawaiian neutrality, T.A. Bailey wrote in his article The United States and Hawaii During the Spanish-American War, “The position of the United States was all the more reprehensible in that she was compelling a weak nation to violate the international law that had to a large degree been formulated by her own stand on the Alabama claims. Furthermore, in line with the precedent established by the Geneva award, Hawai‘i would be liable for every cent of damage caused by her dereliction as a neutral, and for the United States to force her into this position was cowardly and ungrateful. At the end of the war, Spain or cooperating power would doubtless occupy Hawai‘i, indefinitely if not permanently, to insure payment of damages, with the consequent jeopardizing of the defenses of the Pacific Coast.”

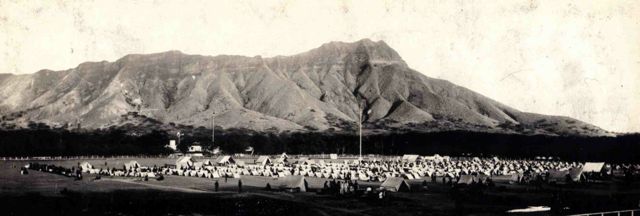

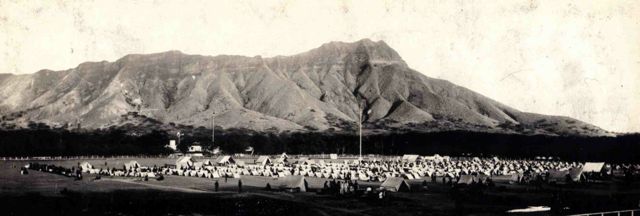

On July 6, the joint resolution passed both House and Senate, despite objections by Congressmen that annexation could only take place by a treaty and not by a domestic statute, and President McKinley signed the measure on July 7, 1898. On August 12, 1898, at 12 noon, the Hawaiian Kingdom was invaded by the United States with full military display on the grounds of the ‘Iolani Palace. The first military base was Camp McKinley established on August 16, 1898 at Kapi‘olani Park adjacent to the famous Waikiki beach and Diamond Head mountain.

Since the invasion, the Hawaiian Kingdom has served as a base of operations for United States troops during World War I and World War II. In 1947, the United States Pacific Command (USPACOM), being a unified combatant command, was established as an outgrowth of the World War II command structure, with its headquarters on the Island of O‘ahu. USPACOM has served as a base of operations during the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Gulf War, the Afghan War, the Iraq War, and the current war against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). There are currently 118 U.S. military sites throughout the Hawaiian Kingdom that comprise 230,929 acres (20%) of Hawaiian territory.

The United States Navy’s Pacific Fleet headquartered at Pearl Harbor on the Island of O‘ahu also hosts the Rim of the Pacific Exercise (RIMPAC) every other even numbered year, which is the largest international maritime warfare exercise. RIMPAC is a multinational, sea control and power projection exercise that collectively consists of activity by the U.S. Army, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Naval forces, as well as military forces from other foreign States. During the month long exercise, RIMPAC training events and live fire exercises occur in open-ocean and at the military training locations throughout the Hawaiian Islands. In 2014, Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Colombia, France, India, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, People’s Republic of China, Peru, Republic of Korea, Republic of the Philippines, Singapore, Tonga, and the United Kingdom participated in the RIMPAC exercises.

Since the belligerent occupation by the United States began on August 12, 1898 during the Spanish-American War, the Hawaiian Kingdom, as a neutral state, has been in a war of aggression for over a century. Although it is not a state of war in the technical sense that was produced by a declaration of war, it is, however, a war in the material sense that Yoram Dinstein’s War, Aggression and Self-Defense, 2nd ed., p. 16, says, is “generated by actual use of armed force, which must be comprehensive on the part of at least one party to the conflict.” The military action by the United States on August 12, 1898 against the Hawaiian Kingdom triggered the change from a state of peace into a state of war of aggression—jus in bello, where the laws of war would apply.

When neutral territory is occupied, however, the laws of war are not applied in its entirety. According to Sakuye Takahashi’s International Law applied to the Russo-Japanese War, p. 251, Japan limited its application of the Hague Convention to its occupation of Manchuria, being a province of a neutral China, in its war against Russia, to Article 42—on the elements and sphere of military occupation, Article 43—on the duty of the occupant to respect the laws in force in the country, Article 46—concerning family honour and rights, the lives of individuals and their private property as well as their religious conviction and the right of public worship, Article 47—on prohibiting pillage, Article 49—on collecting the taxes, Article 50—on collective penalty, pecuniary or otherwise, Article 51—on collecting contributions, Article 53—concerning properties belonging to the state or private individuals, which may be useful in military operations, Article 54—on material coming from neutral states, and Article 56—on the protection of establishments consecrated to religious, warship, charity, etc.

Hawai‘i’s invasion and occupation was anomalous and without precedent. The closest similarity to the Hawaiian situation would not take place until sixteen years later when Germany occupied the neutral States of Belgium and Luxembourg in its war against France from 1914-1918, and its second war against France where both States were occupied again from 1940-1945. The Allies considered Germany’s actions to be acts of aggression. According to James Wilford Garner’s International Law and the World War, vol. II, p. 251, the “immunity of a neutral State from occupation by a belligerent is not dependent upon special treaties, but is guaranteed by the Hague convention as well as the customary law of nations.”

Now that this information is coming to light after a century of indoctrination through “Americanization,” the entire world is being transformed by the harsh reality that Hawai‘i has been in a region of war since 1898. Stemming from this reality is the ongoing commission of war crimes, as well as defects in real property ownership that affect investments, such as mortgage-backed securities. The subprime mortgage crisis took place as a result of mortgages in these securities going into foreclosures, but a new crisis on the horizon is that these mortgages that originated in the Hawaiian Islands were never valid in the first place. Hawaiian Kingdom law was not complied with in the transfer of real property and the securing of mortgages since January 17, 1893.

In light of this severity, the acting Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom has developed a comprehensive plan through the decree of provisional laws to address this problem head on that is based on international law and precedents. The acting government is in the process of implementation according to the laws of war.