By Jon Letman, Truthout

“You can’t spend what you ain’t got; you can’t lose what you ain’t never had.” – Muddy Waters

“You can’t spend what you ain’t got; you can’t lose what you ain’t never had.” – Muddy Waters

“How long do we have to stay in Bosnia, how long do we have to stay in South Korea, how long are we going to stay in Japan, how long are we going to stay in Germany? All of those: 50, 60 year period. No one complains.” – Sen. John McCain

Imagine if you grew up being told that you had been adopted, only to learn that you were, in fact, kidnapped. That might spur you to start searching for the adoption papers. Now imagine that you could find no papers and no one could produce any.

That’s how Dr. David Keanu Sai, a retired Army Captain with a PhD in political science and instructor at Kapiolani Community College in Hawaii, characterizes Hawaii’s international legal status. Since 1993, Sai has been researching the history of the Kingdom of Hawaii and its complicated relationship to the United States.

Over the last 17 years, Sai has lectured and testified publicly in Hawaii, New Zealand, Canada, across the US, at the United Nations and at the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague on Hawaiian land issues on Hawaii’s international status and how Hawaii came to be regarded as a US territory and, eventually, the 50th state.

To explain why he and others insist that Hawaii is not now and never has been lawfully part of the United States, Sai presents an overview of Hawaii’s feudal land system and its history as an independent, sovereign kingdom prior to the overthrow of Queen Liliuokalani on January 16, 1893.

Sai likens his lectures to a scene in the film The Matrix in which the character Morpheus tells Neo, “Remember, all I’m offering is the truth. Nothing more.”

“You guys are going to swallow the little red pill and will find that what you thought you knew may not be what actually was,” Sai warns his audiences. Like The Matrix, which is an assumption of a false reality, Hawaii’s history needs to be reexamined through a legal framework, he says. “What I’ve done is step aside from politics and power and look at Hawaii not through an ethnic or cultural lens, but through the rule of law.”

“A lot of sovereignty groups assume they don’t have it. Sovereignty never left. We just don’t have a government.” – Dr. David Keanu Sai

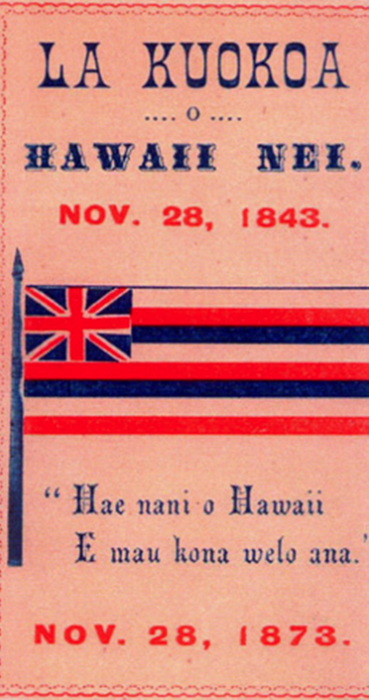

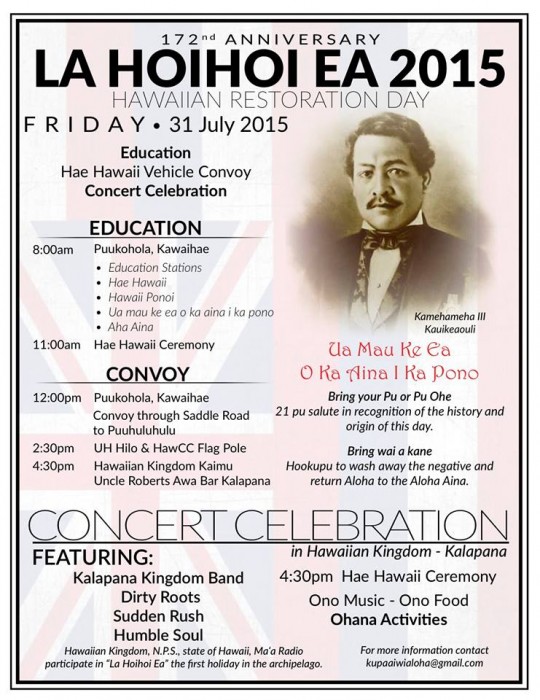

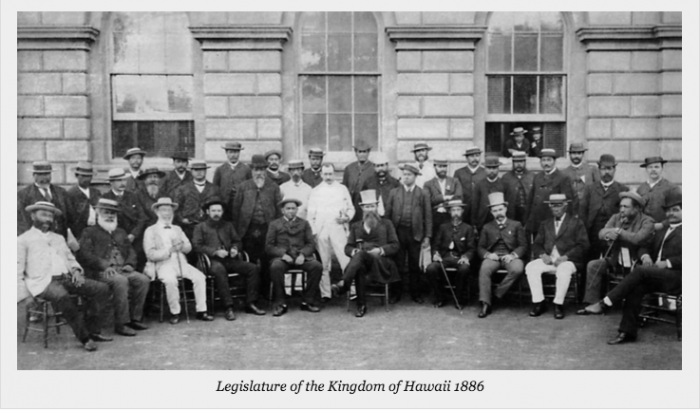

Sai’s lectures review history from 1842, when the Hawaiian Kingdom under King Kamehameha III sent envoys to France, Great Britain and the United States to secure recognition of Hawaii’s sovereignty. US President John Tyler recognized Hawaiian independence on December 19, 1842, with France and Great Britain following in November of 1843. November 28 became recognized as La Kuokoa (Independence Day).

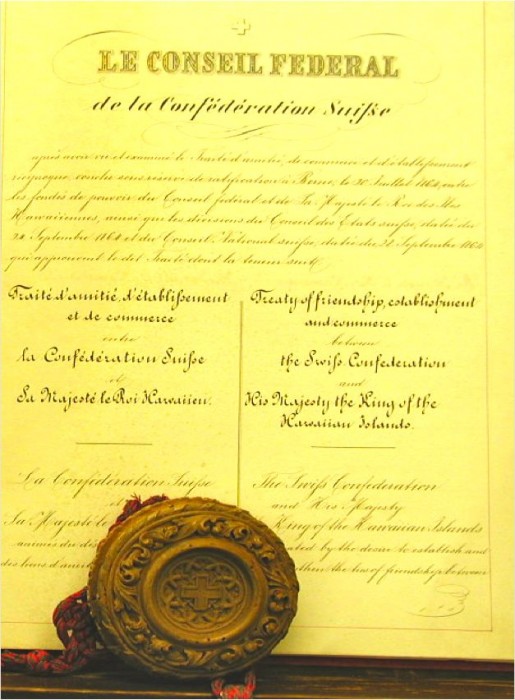

Over the next 44 years, Hawaiian independence was recognized by more than a dozen countries across Europe, Asia and the Pacific, with each establishing foreign embassies and consulates in Hawaii. By 1893, the Kingdom of Hawaii had opened 90 embassies and consulates around the world, including Washington, DC, with consul generals in San Francisco and New York. The United States opened its own embassy in Hawaii after entering into a treaty of friendship, commerce and navigation on December 20, 1849.

In 1854, in response to concerns about naval battles potentially being fought in the Pacific region during the Crimean war, King Kamehameha III declared Hawaii to be a neutral state, a “Switzerland of the Pacific.”

As recently as 2005, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals acknowledged that in 1866, “the Hawaiian Islands were still a sovereign kingdom”; prior to that, in 2004, the Court referred to Hawaii as a “co-equal sovereign alongside the United States.” Likewise, in 2001, the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague acknowledged in an arbitration award that “in the 19th century the Hawaiian Kingdom existed as an independent State recognized as such by the United States of America, the United Kingdom and various other States … .”

Hawaii’s fate changed forever on January 16, 1893 when, motivated by influential naval officer Alfred Thayer Mahan and the US Ambassador to Hawaii – with support from an expansionist US Congress wishing to extend its military presence into the Pacific – US troops landed on Oahu in violation of Hawaiian sovereignty and over the protest of both the Governor of Oahu and the Kingdom of Hawaii’s Minister of Foreign Affairs.

One day later, six ethnic European Hawaiian subjects, including Sanford Dole and seven foreign businessmen, under the name the “Citizen’s Committee of Public Safety,” with the protection of the US military, formally declared themselves to be the new provisional government of the Hawaiian Islands – effectively a bloodless coup.

This marriage of convenience between non-ethnic Hawaiian subjects who wished to operate their sugar cane businesses tariff-free in the American market and a US government and military seeking to advance its own position in the Pacific conspired to overthrow the government of a sovereign foreign nation, Sai tells his audiences.

One month later, members of a group claiming to be the new provisional government of Hawaii traveled to Washington, where they signed a “treaty of cession” which went from President Benjamin Harrison to the US Senate. Queen Liliuokalani’s protests to Harrison were ignored.

When the new US president Grover Cleveland assumed power, he was promptly presented with the Queen’s protest demanding an investigation of their diplomat and US troops, as well as of the coup. Cleveland, after withdrawing the treaty before it could be ratified by the Senate, initiated an investigation called the Blount Report. The investigation found that both the US military and the US Ambassador to Hawaii had violated international law and that the US was obliged to restore the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom to its pre-overthrow status.

In November of 1893, President Cleveland negotiated an agreement to fully restore the government of Queen Liliuokalani under the condition she grant amnesty to all involved in her overthrow. A formal declaration accepting Cleveland’s terms of restoration came from the queen in December 1893.

This executive agreement between President Grover Cleveland and Queen Liliuokalani, Sai says, is binding under both international and US federal law and precludes any other legal actions under the doctrine of estoppel. Yet the US Congress obstructed President Cleveland’s efforts to fulfill his agreement with the queen, just as a self-proclaimed provisional government named itself the “Republic of Hawaii.”

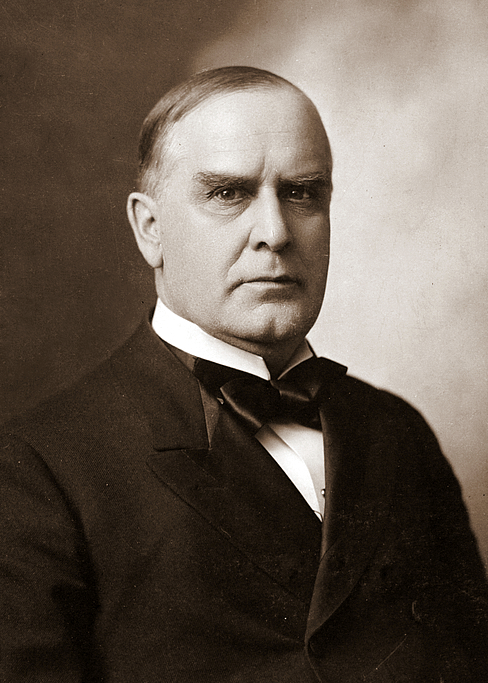

By the spring of 1897 Cleveland had left office, succeeded by President William McKinley. Soon after, representatives of the “Republic of Hawaii” attempted to fully cede all public, government and crown lands to the United States, even as Liliuokalani continued protesting to the US State Department.

In support of the queen and fighting attempts to cede Hawaii, some 38,000 Hawaiian subjects signed petitions against annexation, and by March of 1898, a second attempt to annex Hawaii failed.

Here things accelerate, Sai explains. With the outbreak of war with Spain in April 1898, the drive to expand US naval power into the Pacific to counter Spanish influence in the Philippines and Guam reached a new urgency.

Two weeks after declaring war on Spain, US Rep. Francis Newlands (D-Nevada) submitted a resolution calling for the annexation of Hawaii by the United States. Influential military figures like Rear Admiral Alfred T. Mahan and General John Schofield testified that the possession of Hawaii by the United States was of “paramount importance.” It was in this atmosphere that the Newlands Resolution moved from the House to the Senate and became a joint resolution which President McKinley signed, claiming to have successfully annexed the Hawaiian Islands.

On August 12, 1898, the Hawaiian flag was lowered, the American flag raised, and the Territory of Hawaii formally declared.

But Sai points out that a Congressional joint resolution is American legislation restricted to the boundaries of the United States. The key to Hawaii’s legal status, he says, remains with the 1893 executive agreement between two heads of state: President Grover Cleveland and Queen Liliuokalani.

Unlike other land acquisitions made by cession and voluntary treaties with the French, Spanish, British, Russia and the 1848 Guadalupe Hidalgo Treaty that ended the Mexican-American war, Sai notes there is no treaty of cession, and thus no ceded lands, by then-acting head of state Queen Liliuokalani.

Today, one hundred and seventeen years after US Marines landed on Oahu and helped coup leaders overthrow the Hawaiian Kingdom, what Sai calls “the myth of Hawaiian statehood” is perpetuated, indeed celebrated, on the third Friday of each August, as Statehood Day.

“America today can no more annex Iraq through a joint resolution than it could acquire Hawaii by joint resolution in 1898. Saddam Hussein’s government, the Baathist party … was annihilated by the United States. But by overthrowing the government, that did not also mean Iraq was overthrown as a sovereign state. Iraq still existed, but it did not have a government,” says Sai.

In his doctoral dissertation, Sai successfully argued that to date, under international laws, Hawaii is in fact not a legal territory of the Unites States, but instead a sovereign kingdom, albeit one lacking its own acting government.

The entity that overthrows a government, Sai says, bears the responsibility to administer the laws of the occupied state.

Sai says that despite what people have been led to believe, the Congressional joint resolution and US failed attempts to annex Hawaii are American laws limited to American territory. He stresses that the executive agreement of 1893 between President Cleveland and Hawaii’s Queen continues to take precedence over any other subsequent actions.

Sai says this all has the potential to completely alter any claims on public or private land ownership, all State of Hawaii government bodies and the presence and activities of the US military in Hawaii, specifically the US Pacific Command (PACOM), the preeminent military authority overseeing operations in the Pacific, Oceania and East Asia.

Among the potential impacts of Sai’s argument is the possibility that the United States’ oldest and arguably most important strategic power center (PACOM’s headquarters are at Camp Smith, near Pearl Harbor) is now facing a legal challenge and occupies territory of questionable legal status.

Sai has presented this information not only in arbitration proceedings at the Permanent Court of Arbitration at the World Court at the Hague and in a complaint filed with the UN Security Council, but in 2001, at the invitation of Lieutenant General James Dubik, before the officer’s corps of the 25th Infantry Division at Schoefield Barracks on Oahu.

After Sai’s presentation before some one hundred officers and their spouses, he says, “You could hear a pin drop. They knew what I was talking about — I didn’t have to say ‘war crimes.'” Sai cited the regulations on the occupation of neutral countries in Hague Convention No. 6.

University of Hawaii Press, which reviewed and approved Sai’s dissertation for publication, indicates Sai’s arguments have “profound legal ramifications.” Sai himself says the case calls into question the legal authority of Senator Daniel Inouye, President Obama and others. After all, both Daniel Inouye and Barack Obama were born in Hawaii which, Sai points out, is not a legal US territory.

On June 1, 2010, Sai advanced his case and filed a lawsuit with the US District Court for the District of Columbia naming Barack H. Obama, Hillary D. R. Clinton, Robert M. Gates, (now former) Governor Linda Lingle and Admiral Robert F. Willard of the US Pacific Command as defendants.

Sai cites the Liliuokalani assignment of executive power as a binding legal agreement which extends from President Cleveland to all successors, including President Obama and his administration, to administer Hawaiian Kingdom law prior to restoring the government.

In the suit, Sai seeks a judgment by the court to declare the 1898 Joint Resolution to provide for annexing the Hawaiian Islands to the United States to be in violation of Hawaiian sovereignty and unconstitutional under US law.

In November, Sai sought to add to the suit as defendants the ambassadors of 35 countries which he says unlawfully maintain consulates in Hawaii in violation of Hawaiian Kingdom law and treaties. These countries include China, India, Russia, Brazil, Australia, Japan and smaller nations like Kiribati, Palau and the tiny enclave of San Marino.

With such a bold case that challenges the very top tier of the United States government and military, it isn’t surprising that not everyone supports Sai’s approach. Some Hawaiian activists privately say Sai’s efforts have the potential to adversely impact other forms of federal recognition such as the Akaka Bill, while others express concerns that such a lawsuit could be at best ineffective and, at worst, result in bad laws.

“In the creation of a society, it’s not only historical justification upon which we need to build Hawaiian sovereignty. We need to bring about better quality of life after independence returns.” – Poka Laenui

Poka Laenui, chairman of the Native Hawaiian Convention, an international delegation of Hawaiians which examines the issues of Hawaiian sovereignty and self-governance, says he does not dispute Sai’s historical claims, nor does he disagree that the US occupies the Hawaiian Islands in violation of international law. He says Sai has made a “very positive contribution.”

He does, however, suggest that Sai’s efforts toward deoccupation could go further or be more inclusive. “I believe what should also be included is decolonization. Along with [Sai’s] analysis, there are many more approaches that are legitimate.”

“Decolonization is a very viable position as well. I’m saying occupation and colonization are on the same spectrum, but colonization goes far deeper. It affects economics, education and value systems like we have in Hawaii today.”

“Hawaii has been squarely named as a country that needs to be decolonized and the US has not followed the appropriate, very clear procedures already set out.” Laenui points out that the United States listed Hawaii as a territory to be decolonized in 1946 in the UN General Assembly Resolution 66 (1).

“We need not only to look at the historical, legal approach, but beyond that … we need to change the deep culture of Hawaii to build a better quality of life,” Laenui says.

Lynette Hiilani Cruz is president of the Ka Lei Maile Alii Hawaiian Civic Club and an assistant professor of anthropology at Hawaii Pacific University. She supports Sai’s efforts and says he provides a “dependable legal basis” for challenging the legality of US claims on Hawaii.

But she also points out there are native Hawaiians who, in spite of the history, are reluctant to associate themselves with the kind of legal challenge Sai is pursuing.

And while some would rather forget historical events, Cruz says, “It is our history, whether you like it or not.” Cruz suggests people visit Sai’s website <hawaiiankingdom.org> and study the original historical documents in order to better understand the basis for Sai’s legal claims.

Dr. Kawika Liu, an inactive attorney with a PhD in politics and a practicing physician, says, “I support many canoes going to the same destination. I’m just a little leery of potentially ending up in a Supreme Court that is extremely hostile to indigenous claims. From my perspective, having litigated a number of native Hawaiian rights cases, I am not sure Sai will make it past procedural matters.”

Liu believes Sai’s characterization of historical and political events is accurate, but says, “You can be very correct in the way you characterize history and still be shot down because of issues of jurisdiction.”

“We’re operating in the courts of the colonizer … and they have their own agenda, which is, to me, reinforcing US hegemony.”

Liu sees the greatest benefit of Sai’s work as raising awareness of the issue. “I think the more awareness that’s raised – eventually the change is going to come.”

One academic who thinks Sai is on the right track is Dr. Jon Kamakawiwoole Osorio, professor of Hawaiian studies at the University of Hawaii. Osorio specializes in the politics of identity in the Hawaiian Kingdom and the colonization of the Pacific and served on Sai’s dissertation committee.

He says Sai knows international law and the laws of occupation as they pertain to Hawaii as well as any academic in Hawaii today.

Yet he recognizes Sai has detractors – those who feel that any kind of interpretation which exalts Western law does a disservice to native people and institutions which thrived without those laws for millennia. Osorio also says that while arguing that Hawaii has a solid international case sounds really good, it doesn’t go very far if the US government simply refuses to acknowledge that case or respond in any way.

So does Osorio think Sai’s efforts are counterproductive or a waste of time?

“I don’t think that’s the case,” Osorio says. “I think most people believe Keanu Sai has really added a tremendous new perspective of the kingdom, lawmaking and the creation of constitutional law in Hawaii.”

He also believes Sai’s argument that sovereignty, once conferred, doesn’t disappear just because it is occupied by another country.

What Sai may be pursuing, Osorio suggests, is to push for a definitive stance by the US government which may take the form of a denial that Hawaiians can claim sovereignty.

“I think Sai’s attempt to push the US, to corner it and force it to acknowledge that it holds Hawaii only by raw power … is an important revelation that would have really important political ramifications.”

“Sai says our sovereignty is still intact. That has been a tremendous gift for the Hawaiian movement because it keeps many of us pursuing independence from the United States instead of simply settling for some other kind of status (such as the Akaka Bill) because we feel like we aren’t legally entitled to it,” Osorio says.

“The violence done against the Hawaiian kingdom at the end of the [19th] century was no less violent just because not a lot of people were killed,” Osorio says. “It violated our laws, it violated our trust, it violated the relationship between our people and our rulers and it continues to this day to stand between any kind of friendly relations between Hawaiians who know this history and the United States.

“Sai’s analysis helped many of us to understand more completely that we don’t have to think of ourselves as Americans — ever.”

Keokani Marciel is a lifelong aloha ʻāina (Hawaiian patriot) and kanaka ʻōiwi (aboriginal Hawaiian) who holds a B.S. in Nutrition Science from the University of California at Davis, and an M.S. in Exercise Science from California University of Pennsylvania. In 2008, Keokani made a career change to mathematics education, and is now beginning an actuarial career. With his background, he brings a quantitative and scientific outlook to the discourse regarding the legal status of Hawaiʻi as an occupied nation-state.

Keokani Marciel is a lifelong aloha ʻāina (Hawaiian patriot) and kanaka ʻōiwi (aboriginal Hawaiian) who holds a B.S. in Nutrition Science from the University of California at Davis, and an M.S. in Exercise Science from California University of Pennsylvania. In 2008, Keokani made a career change to mathematics education, and is now beginning an actuarial career. With his background, he brings a quantitative and scientific outlook to the discourse regarding the legal status of Hawaiʻi as an occupied nation-state.