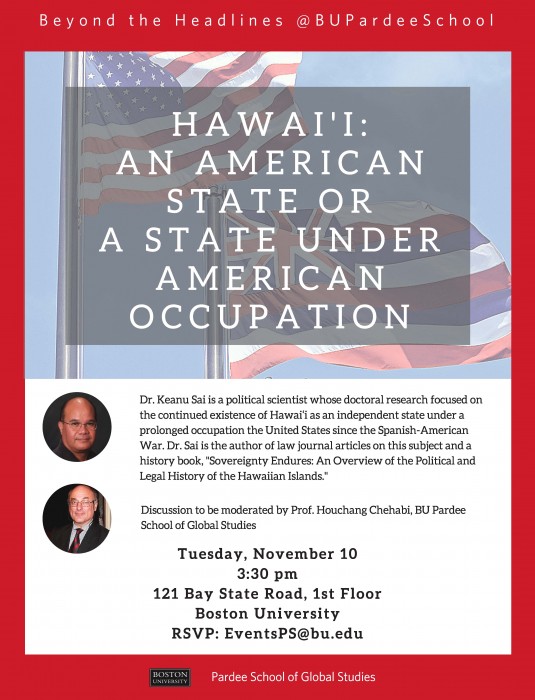

Professor Adil Najam, Dean of The Pardee School for Global Studies at Boston University, has a blog The Knowledge Economy. In its October 30, 2015 edition, the Hawaiian Kingdom Blog is listed under “World” affairs. Dr. Sai will also be lecturing at The Pardee School of Global Studies on November 10, 2015. His lecture is titled Hawai‘i: An American State or a State under American Occupation.

Category Archives: Education

Dr. Sai to Lecture at Boston University’s Pardee School of Global Studies

Lecture Series “Beyond the Headlines” Boston University Pardee School of Global Studies presents: “Hawai’i: An American State or a State Under American Occupation?”

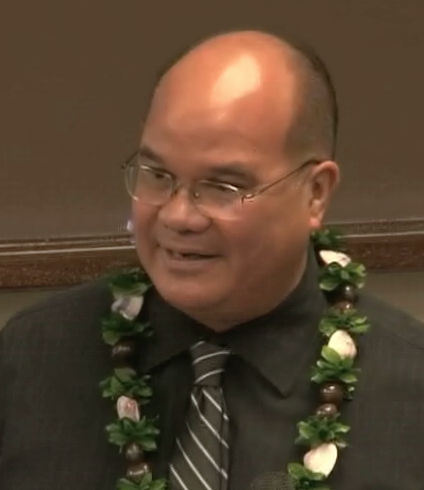

Big Island Video News: Keanu Sai on Na‘i Aupuni, OHA and Cambridge

Big Island Video News: Dr. Keanu Sai is a political scientist at the forefront of an emerging understanding of Hawaii as an existing Kingdom under U.S. occupation. In this lengthy interview, Sai talks about his recent trip to the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom where he was invited to present a paper on Hawaii as a non-European power. He also sets the record straight on his involvement with the Office of Hawaiian Affairs and the letter that was sent to U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry, and the controversial Na’i Aupuni election of delegates to an upcoming Hawaiian nation-building ‘aha.

The paper that Dr. Sai presented at Cambridge was Hawaiian Neutrality: From the Crimean Conflict through the Spanish-American War.

Na‘i Aupuni (Native Hawaiian Convention): What it Is and What it’s Not

An interview of Dr. Keanu Sai by Kale Gumapac, host of the show The Kanaka Express. The interview focuses on Na‘i Aupuni or the Native Hawaiian Convention from a political science, historical and academic standpoint.

https://vimeo.com/143056757

Academics Dispelling the Myths of the Hawaiian Kingdom through Research

An interview of Professor Niklaus Schweizer and Ph.D. candidate Lorenz Gonschor from the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa by Kale Gumapac, host of the show The Kanaka Express. The interview is focuses on dispelling the untruths of the Hawaiian Kingdom that is a part of the research and classroom instruction at the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa.

https://vimeo.com/143006284

The Hawaiian Kingdom as a Non-European Power

An interview of Dr. Keanu Sai and Ph.D. candidate Lorenz Gonschor by Dr. Lynette Cruz on Issues that Matter. The subject of the interview focused on the Hawaiian Kingdom as a non-European Power in the nineteenth century and its relationship with Japan.

https://vimeo.com/142326302

Fifteen Academic Scholars from around the World meet at Cambridge, UK

From September 10-12, 2015, fifteen academic scholars from around the world who were political scientists and historians came together to present papers on non-European powers at a conference/workshop held at the University of Cambridge, United Kingdom. Attendees of the conference were by invitation only and the papers presented at the conference are planned to be published in a volume with Oxford University Press.

From September 10-12, 2015, fifteen academic scholars from around the world who were political scientists and historians came together to present papers on non-European powers at a conference/workshop held at the University of Cambridge, United Kingdom. Attendees of the conference were by invitation only and the papers presented at the conference are planned to be published in a volume with Oxford University Press.

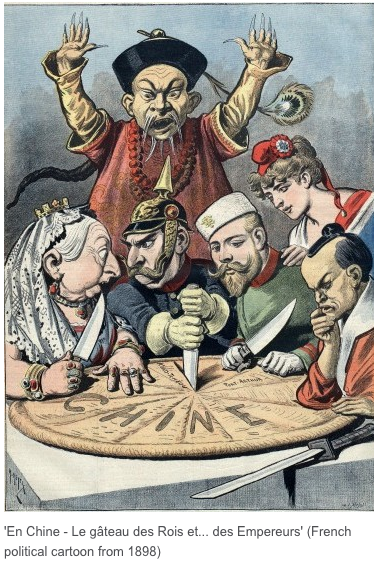

The theme of the conference was Non-European Powers in the Age of Empire. These non-European countries included Hawai‘i, Iran, Turkey, China, Ethiopia, Japan, Korea, Thailand, and Madagascar. Dr. Keanu Sai was one of the invited academic scholars and his paper is titled “Hawaiian Neutrality: From the Crimean Conflict through the Spanish-American War.”

Many of these scholars were unaware of the history of the Hawaiian Kingdom and its “full” membership in the family of nations as a sovereign and independent state. What stood out for them was the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom because it was only the government that was illegally overthrown by the United States and not the Hawaiian state, which is the international term for country. The belief that Hawai‘i lost its independence was dispelled and that its current status is a state under a prolonged American occupation since the Spanish-American War.

What was a surprise was that the Hawaiian Kingdom was the only non-European Power to have been a co-equal sovereign to European Powers throughout the 19th century. All other non-European Powers were not recognized as full sovereign states until the latter part of the 19th century and the turn of the 20th century. During this time European Powers imposed their laws within the territory of these countries under what has been termed “unequal treaties.”

Since 1858, Japan had been forced to recognize the extraterritoriality of American, British, French, Dutch and Russian law operating within Japanese territory. According to these treaties, citizens of these countries while in Japan could only be prosecuted under their country’s laws and by their country’s Consulates in Japan called “Consular Courts.” Under Article VI of the 1858 American-Japanese Treaty, it provided that “Americans committing offenses against Japanese shall be tried in American consular courts, and when guilty shall be punished according to American law.” The Hawaiian Kingdom’s 1871 treaty with Japan also had this provision, where it states under Article II that Hawaiian subjects in Japan shall enjoy “at all times the same privileges as may have been, or may hereafter be granted to the citizens or subjects of any other nation.” This was a sore point for Japanese authorities who felt Japan’s sovereignty should be fully recognized by these states.

While King Kalakaua was visiting Japan in 1881, Emperor Meiji “asked for Hawai‘i to grant full recognition to Japan and thereby create a precedent for the Western powers to follow.” Kalakaua was unable to grant the Emperor’s request, but it was done by his successor Queen Lili‘uokalani. Hawaiian recognition of Japan’s full sovereignty and repeal of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s consular jurisdiction in Japan provided in the Hawaiian-Japanese Treaty of 1871, would take place in 1893 by executive agreement through exchange of notes.

While King Kalakaua was visiting Japan in 1881, Emperor Meiji “asked for Hawai‘i to grant full recognition to Japan and thereby create a precedent for the Western powers to follow.” Kalakaua was unable to grant the Emperor’s request, but it was done by his successor Queen Lili‘uokalani. Hawaiian recognition of Japan’s full sovereignty and repeal of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s consular jurisdiction in Japan provided in the Hawaiian-Japanese Treaty of 1871, would take place in 1893 by executive agreement through exchange of notes.

By direction of Her Majesty Queen Lili‘uokalani, R.W. Irwin, Hawaiian Minister to the Court of Japan in Tokyo sent a diplomatic note to Mutsu Munemitsu, Japanese Minister of Foreign Affairs on January 18, 1893 announcing the Hawaiian Kingdom’s abandonment of consular jurisdiction. Irwin stated:

By direction of Her Majesty Queen Lili‘uokalani, R.W. Irwin, Hawaiian Minister to the Court of Japan in Tokyo sent a diplomatic note to Mutsu Munemitsu, Japanese Minister of Foreign Affairs on January 18, 1893 announcing the Hawaiian Kingdom’s abandonment of consular jurisdiction. Irwin stated:

“Her Hawaiian Majesty’s Government reposing entire confidence in the laws of Japan and the administration of justice in the Empire, and desiring to testify anew their sentiments of cordial goodwill and friendship towards the Government of His Majesty the Emperor of Japan, have resolved to abandon the jurisdiction hitherto exercised by them in Japan.

It therefore becomes my agreeable duty to announce to your Excellency, in pursuance of instructions from Her Majesty’s Government, and I now have the honour formally to announce, that the Hawaiian Government do fully, completely, and finally abandon and relinquish the jurisdiction acquired by them in respect of Hawaiian subjects and property in Japan, under the Treaty of the 19th August, 1871.

There are at present from fifteen to twenty Hawaiian subjects residing in this Empire, and in addition about twenty-five subjects of Her Majesty visit Japan annually. Any information in my possession regarding these persons, or any of them, is at all times at your Excellency’s disposal.

While this action is taken spontaneously and without condition, as a measure demanded by the situation, I permit myself to express the confident hope entertained by Her Majesty’s Government that this step will remove the chief if not the only obstacle standing in the way of the free circulation of Her Majesty’s subjects throughout the Empire, for the purposes of business and pleasure in the same manner as is permitted to foreigners in other countries where Consular jurisdiction does not prevail. But in the accomplishment of this logical result of the extinction of Consular jurisdiction, whether by the conclusion of a new Treaty or otherwise, Her Majesty’s Government are most happy to consult the convenience and pleasure of His Imperial Majesty’s Government.”

On April 10, 1894, Foreign Minister Munemitsu, responded, “The sentiments of goodwill and friendship which inspired the act of abandonment are highly appreciated by the Imperial Government, but circumstances which it is now unnecessary to recapitulate have prevented an earlier acknowledgment of you Excellency’s note.”

This dispels the commonly held belief among historians that Great Britain was the first state to abandon its extraterritorial jurisdiction in Japan under the Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Commerce and Navigation, which was signed on July 16, 1894. The action taken by the Hawaiian Kingdom did serve as “precedent for the Western powers to follow.”

Dr. Sai encourages everyone to read his paper “Hawaiian Neutrality: From the Crimean Conflict through the Spanish-American War” that was presented at Cambridge, which covers Hawai‘i’s political history from the celebrated King Kamehameha I to the current state of affairs today, and the remedy to ultimately bring the prolonged occupation to an end.

Dr. Sai to Present at the University of Cambridge, UK

From September 10-12, 2015, the United Kingdom’s University of Cambridge’s Centre for Research in the Arts, Social Science and Humanities will be holding an academic conference “Sovereignty and Imperialism: Non-European Powers in the Age of Empire.” From the conference’s website:

“In the heyday of empire, most of the world was ruled, directly or indirectly, by the European powers. On the eve of the First World War, only a few non-European states had maintained their formal sovereignty: Abyssinia (Ethiopia), China, Japan, the Ottoman Empire, Persia (Iran), and Siam (Thailand). Some others kept their independence for a while, but then succumbed to imperial powers, such as Hawaii, Korea, Madagascar, and Morocco. Facing imperialist incursion, the political elites of these countries sought to overcome their political vulnerability by engaging with the European powers and seeking recognition as equals.

“In the heyday of empire, most of the world was ruled, directly or indirectly, by the European powers. On the eve of the First World War, only a few non-European states had maintained their formal sovereignty: Abyssinia (Ethiopia), China, Japan, the Ottoman Empire, Persia (Iran), and Siam (Thailand). Some others kept their independence for a while, but then succumbed to imperial powers, such as Hawaii, Korea, Madagascar, and Morocco. Facing imperialist incursion, the political elites of these countries sought to overcome their political vulnerability by engaging with the European powers and seeking recognition as equals.

The conference ‘Sovereignty and Imperialism: Non-European Powers in the Age of Empire’ will explore how diplomats, military officials, statesmen, and monarchs of the independent non-European states struggled to keep European imperialism at bay. It will address four major aspects of the relations of these countries with the Western imperial powers: armed conflict and military reform (Panel 1); capitulations, unequal treaties, and subsequent engagement with European legal codes (Panel 2); royalty and courts (Panel 3); and diplomatic encounters (Panel 4). Bringing together scholars from across the world, the conference will be the first attempt to provide comparative perspectives on the non-European powers’ engagement with the European empires in the era of high imperialism.”

Dr. David Keanu Sai was 1 of 15 scholars from across the world that was invited to present their research and expertise that centers on non-European States. Dr. Sai’s research focuses on the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent and sovereign state and its continuity to date under an illegal and prolonged occupation by the United States of America since the Spanish-American War. He will be presenting a paper titled “Hawaiian Neutrality: From the Crimean Conflict to the Spanish-American War.” The following is Dr. Sai’s abstract for his paper:

Dr. David Keanu Sai was 1 of 15 scholars from across the world that was invited to present their research and expertise that centers on non-European States. Dr. Sai’s research focuses on the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent and sovereign state and its continuity to date under an illegal and prolonged occupation by the United States of America since the Spanish-American War. He will be presenting a paper titled “Hawaiian Neutrality: From the Crimean Conflict to the Spanish-American War.” The following is Dr. Sai’s abstract for his paper:

“Only a decade since the Anglo-French proclamation of November 28, 1843 recognizing the Hawaiian Islands as an independent and sovereign State, the Hawaiian Kingdom would find itself being a participant State, during the Crimean conflict, in the abolishment of privateering and the formation of international rules protecting neutral goods. This set the stage for Hawaiian authorities to secure international recognition of its neutrality. Unlike States that were neutralized by agreement between third States, e.g. Luxembourg and Belgium, the Hawaiian Kingdom took a proactive approach to secure its neutrality through diplomacy and treaty provisions by making full use of its global location, which undoubtedly was double-edged. On the one hand, Hawai‘i was a beneficial asylum, being neutral territory, for all States at war in the Pacific Ocean, while on the other hand it was coveted by the United States for its military and strategic importance. This would eventually be revealed during the Spanish-American War when the United States deliberately violated the neutrality of the Hawaiian Islands and occupied its territory in order to conduct military campaigns in the Spanish colonies of Guam and Philippines, which was similar, in fashion, to Germany’s occupation of Luxembourg and the violation of its neutrality when it launched attacks into France during the First World War. The difference, however, is that Germany withdrew after four years of occupation, whereas the United States remained and implemented a policy of ‘denationalization’ in order to conceal the prolonged occupation of an independent and sovereign State. This paper challenges the commonly held belief that Hawai‘i lost its independence and was incorporated into the United States during the Spanish-American War. Rather, Hawai‘i remains a State by virtue of the same positive rules that preserved the independence of the occupied States of Europe during the First and Second World Wars.”

Hawai‘i’s History, International Law and Global Support with Aloha

On August 5, 2015, a panel was on Hawai‘i’s history and international law was held at the Wailuku Civic Center, Island of Maui. The panel was moderated by Kale Gumapac and the panelist included Professor Kaleikoa Ka‘eo, University of Hawai‘i Maui College, Dr. Keanu Sai, University of Hawai‘i Windward Community College, Kaho‘okahi Kanuha, teacher at Punanaleo o Kona, and Dexter Ka‘iama, attorney at law. The organizer of the event was Ku‘uipo Naone.

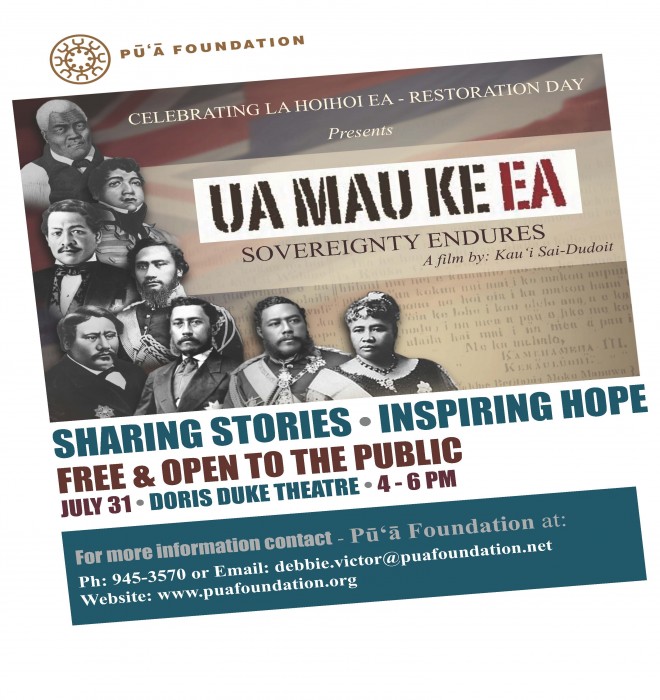

Ua Mau Ke Ea – Sovereignty Endures Film at Doris Duke Theater in Honolulu

Here’s the trailer of Ua Mau Ke Ea – Sovereignty Endures:

New Zealand News: United States Occupation of Hawai‘i

Te Karere New Zealand Television (NZTV) covers the illegal occupation of Hawai‘i by the United States. For the past week Dr. Keanu Sai has been meeting with tribal and political leaders in an act to raise awareness and gain support from Māori and New Zealanders on the illegal occupation of Hawai’i by the United States of America.

During his visit to New Zealand, Dr. Sai has met with Members of Parliament, a Cabinet Minister of the New Zealand government, Political Party Officials, Academics, and Tribal Leaders regarding the prolonged occupation of Hawai‘i by the United States. Dr. Sai brought to their attention the recent decision by the Swiss Federal Criminal Court specifically naming the State of Hawai‘i Governor Neal Abercrombie, Lt. Governor Shan Tsustui, the director of the Department of Taxation Frederik Pablo and his deputy Joshua Wisch, and the CEO of Deutsche Bank, Josef Ackermann.

In these meetings, Dr. Sai explained:

As my fellow countrymen and women are awakening to the stark reality that we’ve been under an illegal and prolonged occupation by the United States since the Spanish-American War, 1898, there are profound economic, legal and political ramifications that transcend Hawai‘i. My country was seized by the United States for military interests, and the belligerent occupation was disguised through lies and effected through a program of denationalization—Americanization—in the schools at the turn of the 19th century.

This revelation is reconnecting Hawai‘i to the international community and its treaty partners regarding the violations of rights and war crimes committed against the citizens and subjects of foreign states who have visited, resided or have done business in the Hawaiian Islands. My country’s treaty partners include Austria, Hungary, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Russia, Spain, Switzerland, Sweden, Norway, the United States, and the United Kingdom, to include Antigua and Barbuda, Australia, The Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Canada, Grenada, Jamaica, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Solomon Islands, and Tuvalu, as member states of the Commonwealth Realm.

The State of Hawai‘i has evaded a precise definition of standing in international law because it has pretended to be a government within the territorial borders of the United States, when in fact it is a private organization operating outside of the United States. The U.S. Congress created the State of Hawai‘i in 1959 by a Congressional Act, but since Congress has no extra-territorial effect it could not vest the State of Hawai‘i with governmental powers outside of its territory in an occupied state. According to the laws and customs of war, the State of Hawai‘i is defined as an Armed Force of the United States, which pretends to be a government.

As an Armed Force, the State of Hawai‘i is presently operating from a position of no lawful authority, and everything that it has done and that it will do is unlawful. From the creation and registration of commercial entities, the collection of tax revenues, the conveyance of real estate, to judicial proceedings, the State of Hawai‘i cannot claim to be a government de jure. This has the potential of generating catastrophic economic, legal and political ramifications in foreign countries, and the mandate for some of these countries, which includes New Zealand (International Crimes and International Criminal Court Act 2000), is to prosecute war crimes committed in the Hawaiian Islands under universal jurisdiction.

Her British Majesty Queen Victoria was the first to recognize Hawaiian independence in a joint proclamation with the French on November 28, 1843, and subsequently entered into a Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation on July 10, 1851. In 1893, my country maintained a Legation in London, and two Consulates in the cities of Auckland and Dunedin, and the United Kingdom maintained a Legation and a Consulate in Honolulu. These Consulates were established in accordance with Article XII of the 1851 Hawaiian-British Treaty, which provides:

“It shall be free for each of the two contracting parties to appoint consuls for the protection of trade, to reside in the territories of the other party; but before any consul shall act as such, he shall, in the usual form, be approved and admitted by the Government to which he is sent; and either of the contracting parties may except from the residence of consuls such particular places as either of them may judge fit to be excepted. The diplomatic agents and consuls of the Hawaiian Islands, in the dominions of Her Britannic Majesty, shall enjoy whatever privileges, exemptions and immunities are, or shall be granted there to agents of the same rank belonging to the most favored nation; and, in like manner, the diplomatic agents and consuls of Her Britannic Majesty in the Hawaiian Islands shall enjoy whatever, privileges, exemptions, and immunities are or may be granted there to the diplomatic agents and consuls of the same rank belonging to the most favored nation.”

The New Zealand Government’s recent creation of the New Zealand Consulate General in Honolulu was established by virtue of Article 16 of the 1794 Treaty of Amity, Commerce and Navigation between Great Britain and the United States, also called the “Jay Treaty,” and not the Hawaiian-British Treaty. Therefore, the New Zealand Consulate in Honolulu stands in direct violation of the Hawaiian-British Treaty, and therefore is unlawful. This year, the Swiss authorities were faced with the same circumstances. In a decision by the Swiss Federal Criminal Court Objections Chamber this year, the Court concluded that the 1864 Hawaiian-Swiss Treaty was not cancelled and that the Swiss Consulate in Honolulu is unlawful. These decisions stemmed from war crime complaints filed with Swiss authorities by a Swiss expatriate residing in Hawai‘i and a Hawaiian subject. I represent both men in these proceedings.

The Court specifically named the CEO of Deutsche Bank and high officials of the State of Hawai‘i as alleged war criminals for committing the war crime of pillaging. Allegations of war crimes can only arise if there is an international armed conflict, and the evidence acquired by the Swiss Attorney General that was provided to the Court clearly established that an international armed conflict does exist between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States. According to customary international law, an international armed conflict is not limited to states engaged in hostilities, but also the military occupation of a state’s territory even if it occurred without armed resistance, i.e, Common Article 2, Geneva Conventions.

Report of the U.S. House Committee on Foreign Affairs – Annexation of Hawai‘i

ANNEXATION OF THE HAWAIIAN ISLANDS

(House Committee on Foreign Affairs Report to accompany H. Res. 259, May 17, 1898 (House Report no. 1355, 55th Congress, 2d session)

May 17, 1898.—Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the state of the Union and ordered to be printed.

Mr. Hitt, from the U.S. Congress House Committee on Foreign Affairs, submitted the following

REPORT.

[To accompany H. Res. 259.]

The joint resolution (H. Res. 259) provides for the annexation of the Hawaiian Islands to the United States. The proposition is not new either to the Government of the little Commonwealth in the Pacific, to the United States, or to other nations. It has been apparent for more than fifty years that so small and feeble a Government could not maintain its independence, and that it must ultimately be merged into a greater power. It has been repeatedly seized and Honolulu occupied, and has repeatedly made overtures to the United States to be united with us. In 1829 the French commander, Laplace, seized Honolulu and held it for awhile, after forcing upon the government a harsh treaty. In 1843 it was seized by the British commander, Lord Pawlet, but subsequently released by Great Britain upon the remonstrances of other powers. It was again seized by the French in 1849 and held for a considerable time, but was evacuated after diplomatic pressure from England and the United States.

In 1851 the King, pressed by his perplexities with France and England, delivered to our commissioner a deed of cession of the islands to the United States, to be held until a satisfactory adjustment had been reached with France, and failing that, permanently. In 1854 our Secretary of State, Mr. Marcy, authorized the negotiation of an annexation treaty. The King made a draft satisfactory to him and modifying the one proposed, but before the conclusion was reached he died. In 1893 a treaty was negotiated between our government and that of the Hawaiian Islands for the annexation of the islands to the United States. No word of protest was uttered by any other government. This treaty, while pending before the Senate, was withdrawn by the President, a change of administration having taken place. Again, June 16, 1897, a treaty of annexation, similar in provisions to the joint resolution now proposed, was agreed to by the government of Hawaii and duly ratified by their Senate.

There is, therefore, no undue pressure on the part of the United States as a greater power; no surprise of any one; no possibility of objections by other governments. It is simply the obvious result of the natural course of events through a long period of years thus completed with the cordial consent of the sovereign powers of both Governments. The only question involved is whether the proposed possession of the Hawaiian Islands would be advantageous to the United States.

THEIR STRATEGIC IMPORTANCE.

Recent events In the existing war with Spain have called public attention to what has long been discussed by military and naval authorities—the inestimable importance to the United States of possessing the Hawaiian Islands in case of war with any strong naval power. They lie facing our Pacific coast. Their strategic importance is vastly increased by the fact that they are separated by thousands of miles from any other and more distant group in the northern Pacific Ocean and are the only group facing our coast. In the possession of an enemy they would serve as a secure base for attacking any and all of our Pacific coast cities. In our possession they would deprive the enemy s fleet of all facilities for coaling, supplies, or repairs, and speedily paralyze all his naval operations. The first object of an enemy attacking us on that side of the Republic would be to secure these islands, and in their present condition their possession would fall to the stronger naval power.

The leading nations—England, France, Germany, Japan, Spain, and the United States—have each a Pacific Squadron. Every one of these squadrons is stronger than ours save that of Spain, which is the weakest. Had the war in which we are now engaged been with any of the other powers they might have worsted our fleet and seized the Hawaiian Islands, which are not now defended by any fortification or cannon, thus exactly reversing our recent good fortune at Manila. They would then have had a convenient base for supplies, coal, and repairs, from which to actively harry and devastate our coast. But were we in complete possession of the Hawaiian Islands and they properly prepared for defense (which eminent officers of the Army and Navy stated to the committee could be done at a cost of $500,000), our fleet, even if pressed by a greatly superior sea power, would have an impregnable refuge at Pearl Harbor, backed by a friendly population and militia, with all the resources of the large city of Honolulu and a small but fruitful country. Holding this all important strategic point, the enemy could not remain in that part of the Pacific, thousands of miles from any base, without running out of coal sufficient to get back to their own possessions. The islands would secure both our fleet and our coast.

GENERAL SCHOFIELD’S VIEW.

As General Schofield stated to the committee—

“The most important feature of all is that it economizes the naval force rather than increases it. It is capable of absolute defense by shore batteries, so that a naval fleet, after going there and replenishing its supplies and making what repairs are needed, can go away and leave the harbor perfectly safe to the protection of the army. * * * The Spanish fleet on the Asiatic station was the only one of all the fleets we could have overcome as we did. Of course, that cannot again happen, for we will not be able to pick up so weak a fellow next time. We are liable at any time to get into a war with a nation which has a more powerful fleet than ours, and it is of vital importance, therefore, if we can, to hold the point from which they can conduct operations against our Pacific coast. Especially is that true until the Nicaragua Canal is finished, because we can not send a fleet around from the Atlantic to the Pacific.”

The same eminent and experienced soldier, when asked whether it would be sufficient to have Pearl Harbor without the islands, said we ought to have the islands to hold the harbor; that if left free and neutral complications would arise with foreign nations, who would take advantage of a weak little republic with claims for damages enforced by warships, as is frequently seen. If annexed we would settle any dispute with a foreign nation; that we would be much stronger if we owned the islands as part of our territory, and would then also have the resources of the islands, which are so fertile, for military

supplies; that if we do not have the political control they may become Japanese, and we would be surrounded by a hostile people.

Admiral Walker, who has had long experience in the waters of the Hawaiian Islands, emphatically confirmed the views of General Schofield, especially that it would cost far less to protect the Pacific coast with the Hawaiian Islands than without them; that it would be taking a point of vantage instead of giving it to your enemy.

RISK OF DELAY.

We must face the future in dealing with this proposed annexation. It is impossible for the Republic of Hawaii to maintain a permanent existence preserving in force the influences which are now in the ascendant there and which are cordial and friendly to the United States. Of its mixed population of 109,000 a powerful element is Japanese—24,407—of whom 19,212 are males, almost all of them grown men, for they are not divided as ordinary populations are in the usual proportions of men, women, and children. They are a far stronger element of physical force than the native race, which has diminished until there are now only thirty-odd thousand, of whom, by the usual proportions of population, there are not over 8,000 grown men. The native Hawaiian race cannot in any contingency control the island. It must fall to some foreign people.

The Japanese are intensely Japanese, retaining their allegiance to their Empire and responding to suggestions from the Japanese officials. Very many of them served in the recent war with China. The Japanese Government not long ago demanded of the Hawaiian Government, under their construction of a treaty made in 1871, that the Japanese in the Hawaiian Islands should have equal privileges with all other persons, which would include voting and holding office. This claim was made when a flood of Japanese subjects, under the supervision of the Government of that country, of from 1,000 to 2,000 per month, were being poured into the Hawaiian Islands, threatening a speedy change of the Government into Japanese hands, and ultimately to a Japanese possession. The demand was resisted by the little Republic and a treaty of annexation with the United States arrested it for a time.

Japan protested earnestly to our government against that treaty, but our Secretary of State refused to consider their protest; yet the Japanese government has not withdrawn its demand on the Hawaiian Government, and is waiting to renew and press it with more energy and success if annexation to the United States s rejected by this Congress. It could then in a few months throw many thousands of Japanese subjects into the Hawaiian Islands, completely overwhelming all other influences.

By a clause in our reciprocity treaty with the Hawaiian Islands we have right to establish and maintain a coaling and repair station in Pearl Harbor, which is about 8 miles from the city of Honolulu, and capable of being made one of the best harbors in the world, easily fortified to make it impregnable from the sea. It is the only harbor of such a character in the whole group. We have thus far done nothing toward taking possession, fortifying, or opening the channel into the harbor, so that it is at present utterly useless, but capable of infinite possibilities.

The grant of this harbor to our Government is a part of a reciprocity treaty. After that treaty had been ratified, but before the ratification had been exchanged, the Hawaiian minister and the Secretary of State of the United States exchanged notes which declared that our rights in Pearl Harbor would cease whenever the reciprocity treaty was terminated. That treaty may be terminated upon one year’s notice by either party. It grants advantages in our markets to Hawaiian trade, and concedes to us not only the use of Pearl Harbor, but excludes any other nation from leasing a port or landing, or having any special privilege in the Hawaiian Islands, without the consent of the United States.

With the Japanese element in the ascendant and the Government under Japanese control the treaty would be promptly terminated, and with it our special rights. This would be the first step taken by that active and powerful Government toward the complete incorporation of the islands into the Japanese Empire, and their possession as a strategic point in the northern Pacific from which her strong and increasing fleet would operate. The Japanese Government is now friendly, but that would be the manifest dictate of enlightened self-interest to a wise Japanese statesman.

Annexation, and that alone, will securely maintain American control in Hawaii. Resolutions of Congress declaring our policy, or even a protectorate, will not secure it. The question of a protectorate has been successively considered by Presidents Pierce, Harrison, and McKinley in 1854, 1893, and 1897, and each time rejected because a protectorate imposes responsibility without control. Annexation imposes responsibility, but will give full power of ownership and absolute control.

AMERICAN COMMERCIAL INTERESTS.

The commercial interests of the United States, according to the declarations of our most eminent public men, would be promoted and secured by the union of the two countries. In those islands is an American colony numbering over 3,000 persons, who own practically three-fourths of all the property in the country, and, under the fostering Influence of the reciprocity treaty, trade with the United States has so increased that we now consume almost all Hawaiian exports. The people of the islands purchase from us three-fourths of all their imports, and American ships carry three-fourths of all the foreign trade of the island. American influence is ascendant in the Government, and the character of the American statesmen there in power was forcibly described by Mr. Willis, our minister to Hawaii, who was sent there by Mr. Cleveland in a spirit of hostility to them, but who was a truthful, honorable man, in these words: “They are acknowledged on all sides to be men of the highest integrity and public spirit.”

Hawaiians of American origin are energetic, intelligent, and patriotic, and are holding that outpost of Americanism against Asiatic invasion. If annexation be rejected and foreign influence gets control of the islands, our interests and commerce will fall away. The American in Hawaii looks to the United States to make purchases and there he desires to send what he exports. The Japanese merchant very naturally buys all he can in Japan, and will turn all trade there that is in his power. Our trade with the Hawaiian Islands last year amounted to $18,385,000, and with annexation practically the whole trade with the Hawaiian Islands would come to the United States, and would rapidly increase.

We have now the larger part of the shipping business, 247 American ships being employed in carrying Hawaiian trade in 1896, which would be promoted and increased by annexation. Its past prosperity has depended upon the reciprocity treaty, and if that were abrogated by a party adverse to American interests gaining control this business, like all other American interests, would fall off.

ANNEXATION WOULD END FOREIGN COMPLICATIONS.

In the struggling interests that have recently come into play in the Pacific the separate existence of the Hawaiian Government is liable at any time to raise complications with foreign governments, as in the case mentioned above of the recent interposition of Japan. An independent feeble government is a constant temptation to powerful nations, in the stress of contending interests, to intermeddle and disturb the peace. Once incorporated into the territory of the United States, all this is done away.

CHARACTER OF THE POPULATION.

While the character of the comparatively small population of the Hawaiian Commonwealth is a minor consideration as compared with the transcendent importance of the possession of that strategic point in the Pacific, it may be briefly considered. It is a mixed population, 24,407 Japanese and 21,616 Chinese, or together nearly one-half of the entire 109,020 on the island; but after annexation the Asiatic element would be reduced. The contract system would be terminated, and United States restriction laws as to immigration would be applied. The Hawaiian penal code (paragraph 1571) would gradually send back the Chinese laborers. This annexation joint resolution forbids further Chinese immigration, and under it those now in Hawaii can not come to other parts of the United States. Our recent treaty with Japan, to go into effect next year enables the United States to regulate the immigration of Japanese laborers. The supply being cut off, the number of Asiatics remaining in Hawaii would be very rapidly reduced by natural causes, which are plainly shown by the movements of the Asiatic population in past years; for since 1893, though the flood of Japanese coming in has been strong, the departures each year have been half as many as the arrivals. Like the Chinese, when they have accumulated a moderate competence, the craving for home takes them back. The enormous excess of men coming shows on its face that they do not come to Hawaii to establish homes. The Hawaiian laws exclude them from homestead rights.

These constant and powerful causes operating, if annexation were carried out the Asiatic proportion of the population would rapidly diminish. There is a large element of what are called Portuguese—15,191—but of these, who are a quiet, laborious population, over 7,000 have been born there, educated in the public schools, and speak English as readily as the average American child. They are a useful, orderly people, and rapidly assimilate the American ideas and institutions which now prevail on the islands.

The British element, 2,250, the German, 1,432, and others of European origin, probably 1,000, are elements with which we are perfectly familiar in our own country, which readily sympathize and blend with our own people. They will naturally adhere and cooperate as against Asiatic influence. The native Hawaiian race is decreasing from year to year by some mysterious law which has been in operation for a century. It is reasonable to suppose that within ten years after annexation the inconsiderable population of these islands will not differ widely in character from that of many parts of the United States.

Some effort has been made to that our beet-sugar Industry would be retarded by the admission of Hawaii and the free admission of its sugar product. Raw Hawaiian sugar is now admitted free of duty under the reciprocity treaty. There is so little of it, altogether amounting to not one-tenth of our consumption, that it can not affect the general price of sugar one-tenth of a cent a pound. There are but 80,000 acres of natural sugar-cane lands In Hawaii, and they are all under cultivation, unless it be possibly some that might e irrigated by pumping water from 150 to 600 feet.

There would be one difference after annexation as to the restriction upon Hawaiian sugar. At present, under the reciprocity treaty, all unrefined Hawaiian sugar is admitted free of duty, but not refined sugar. After annexation both refined and unrefined would be admitted free and sugar-refining interests in this country may object to annexation.

It has been objected that the constitution does not confer upon Congress the power to admit “territory,” but only “States.” The same objection was raised to the acquisition of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, because there was nothing in the Constitution expressly authorizing such admission by treaty, and Jefferson himself, who made the purchase, shared the doubt. But we have made eleven such acquisitions of territory, and the courts have sustained such action in all cases. Texas was annexed by a joint resolution of Congress similar to the one proposed now. The island of Navassa, in the Caribbean Sea, and many others have been made territory of the United States under the act of August 18, 1856, authorizing American citizens to take possession of unoccupied guano islands. They are United States territory, subject to our laws. So Midway island in the Pacific, 1,000 miles beyond Hawaii, was occupied, and Congress appropriated $50,000, which was expended trying to create a naval station there. The principle is that the power to acquire territory is an incident of national sovereignty.

The acquisition of these islands does not contravene our national policy or traditions. It carries out the Monroe doctrine, which excludes European powers from interfering in the American continent and outlying islands, but does not limit the United States; and this doctrine has been long applied to these very islands by our Government. As Secretary Blaine said, in 1881—

“The situation of the Hawaiian Islands, giving them strategic control of the north Pacific, brings their possession within range of questions of purely American policy.”

The annexation of these islands does not launch us upon a new policy or depart from our time-honored traditions of caring first and foremost for the safety and prosperity of the United States.

The committee recommend the adoption of the resolutions.

Truthout: Hawai‘i’s Legal Case Against the United States

By Jon Letman, Truthout

“You can’t spend what you ain’t got; you can’t lose what you ain’t never had.” – Muddy Waters

“You can’t spend what you ain’t got; you can’t lose what you ain’t never had.” – Muddy Waters

“How long do we have to stay in Bosnia, how long do we have to stay in South Korea, how long are we going to stay in Japan, how long are we going to stay in Germany? All of those: 50, 60 year period. No one complains.” – Sen. John McCain

Imagine if you grew up being told that you had been adopted, only to learn that you were, in fact, kidnapped. That might spur you to start searching for the adoption papers. Now imagine that you could find no papers and no one could produce any.

That’s how Dr. David Keanu Sai, a retired Army Captain with a PhD in political science and instructor at Kapiolani Community College in Hawaii, characterizes Hawaii’s international legal status. Since 1993, Sai has been researching the history of the Kingdom of Hawaii and its complicated relationship to the United States.

Over the last 17 years, Sai has lectured and testified publicly in Hawaii, New Zealand, Canada, across the US, at the United Nations and at the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague on Hawaiian land issues on Hawaii’s international status and how Hawaii came to be regarded as a US territory and, eventually, the 50th state.

To explain why he and others insist that Hawaii is not now and never has been lawfully part of the United States, Sai presents an overview of Hawaii’s feudal land system and its history as an independent, sovereign kingdom prior to the overthrow of Queen Liliuokalani on January 16, 1893.

Sai likens his lectures to a scene in the film The Matrix in which the character Morpheus tells Neo, “Remember, all I’m offering is the truth. Nothing more.”

“You guys are going to swallow the little red pill and will find that what you thought you knew may not be what actually was,” Sai warns his audiences. Like The Matrix, which is an assumption of a false reality, Hawaii’s history needs to be reexamined through a legal framework, he says. “What I’ve done is step aside from politics and power and look at Hawaii not through an ethnic or cultural lens, but through the rule of law.”

“A lot of sovereignty groups assume they don’t have it. Sovereignty never left. We just don’t have a government.” – Dr. David Keanu Sai

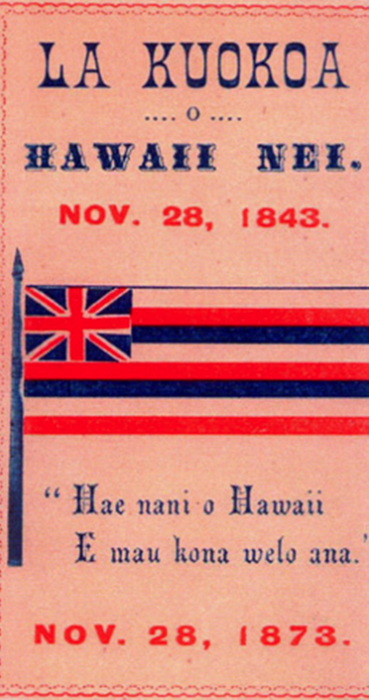

Sai’s lectures review history from 1842, when the Hawaiian Kingdom under King Kamehameha III sent envoys to France, Great Britain and the United States to secure recognition of Hawaii’s sovereignty. US President John Tyler recognized Hawaiian independence on December 19, 1842, with France and Great Britain following in November of 1843. November 28 became recognized as La Kuokoa (Independence Day).

Over the next 44 years, Hawaiian independence was recognized by more than a dozen countries across Europe, Asia and the Pacific, with each establishing foreign embassies and consulates in Hawaii. By 1893, the Kingdom of Hawaii had opened 90 embassies and consulates around the world, including Washington, DC, with consul generals in San Francisco and New York. The United States opened its own embassy in Hawaii after entering into a treaty of friendship, commerce and navigation on December 20, 1849.

In 1854, in response to concerns about naval battles potentially being fought in the Pacific region during the Crimean war, King Kamehameha III declared Hawaii to be a neutral state, a “Switzerland of the Pacific.”

As recently as 2005, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals acknowledged that in 1866, “the Hawaiian Islands were still a sovereign kingdom”; prior to that, in 2004, the Court referred to Hawaii as a “co-equal sovereign alongside the United States.” Likewise, in 2001, the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague acknowledged in an arbitration award that “in the 19th century the Hawaiian Kingdom existed as an independent State recognized as such by the United States of America, the United Kingdom and various other States … .”

Hawaii’s fate changed forever on January 16, 1893 when, motivated by influential naval officer Alfred Thayer Mahan and the US Ambassador to Hawaii – with support from an expansionist US Congress wishing to extend its military presence into the Pacific – US troops landed on Oahu in violation of Hawaiian sovereignty and over the protest of both the Governor of Oahu and the Kingdom of Hawaii’s Minister of Foreign Affairs.

One day later, six ethnic European Hawaiian subjects, including Sanford Dole and seven foreign businessmen, under the name the “Citizen’s Committee of Public Safety,” with the protection of the US military, formally declared themselves to be the new provisional government of the Hawaiian Islands – effectively a bloodless coup.

This marriage of convenience between non-ethnic Hawaiian subjects who wished to operate their sugar cane businesses tariff-free in the American market and a US government and military seeking to advance its own position in the Pacific conspired to overthrow the government of a sovereign foreign nation, Sai tells his audiences.

One month later, members of a group claiming to be the new provisional government of Hawaii traveled to Washington, where they signed a “treaty of cession” which went from President Benjamin Harrison to the US Senate. Queen Liliuokalani’s protests to Harrison were ignored.

When the new US president Grover Cleveland assumed power, he was promptly presented with the Queen’s protest demanding an investigation of their diplomat and US troops, as well as of the coup. Cleveland, after withdrawing the treaty before it could be ratified by the Senate, initiated an investigation called the Blount Report. The investigation found that both the US military and the US Ambassador to Hawaii had violated international law and that the US was obliged to restore the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom to its pre-overthrow status.

In November of 1893, President Cleveland negotiated an agreement to fully restore the government of Queen Liliuokalani under the condition she grant amnesty to all involved in her overthrow. A formal declaration accepting Cleveland’s terms of restoration came from the queen in December 1893.

This executive agreement between President Grover Cleveland and Queen Liliuokalani, Sai says, is binding under both international and US federal law and precludes any other legal actions under the doctrine of estoppel. Yet the US Congress obstructed President Cleveland’s efforts to fulfill his agreement with the queen, just as a self-proclaimed provisional government named itself the “Republic of Hawaii.”

By the spring of 1897 Cleveland had left office, succeeded by President William McKinley. Soon after, representatives of the “Republic of Hawaii” attempted to fully cede all public, government and crown lands to the United States, even as Liliuokalani continued protesting to the US State Department.

In support of the queen and fighting attempts to cede Hawaii, some 38,000 Hawaiian subjects signed petitions against annexation, and by March of 1898, a second attempt to annex Hawaii failed.

Here things accelerate, Sai explains. With the outbreak of war with Spain in April 1898, the drive to expand US naval power into the Pacific to counter Spanish influence in the Philippines and Guam reached a new urgency.

Two weeks after declaring war on Spain, US Rep. Francis Newlands (D-Nevada) submitted a resolution calling for the annexation of Hawaii by the United States. Influential military figures like Rear Admiral Alfred T. Mahan and General John Schofield testified that the possession of Hawaii by the United States was of “paramount importance.” It was in this atmosphere that the Newlands Resolution moved from the House to the Senate and became a joint resolution which President McKinley signed, claiming to have successfully annexed the Hawaiian Islands.

On August 12, 1898, the Hawaiian flag was lowered, the American flag raised, and the Territory of Hawaii formally declared.

But Sai points out that a Congressional joint resolution is American legislation restricted to the boundaries of the United States. The key to Hawaii’s legal status, he says, remains with the 1893 executive agreement between two heads of state: President Grover Cleveland and Queen Liliuokalani.

Unlike other land acquisitions made by cession and voluntary treaties with the French, Spanish, British, Russia and the 1848 Guadalupe Hidalgo Treaty that ended the Mexican-American war, Sai notes there is no treaty of cession, and thus no ceded lands, by then-acting head of state Queen Liliuokalani.

Today, one hundred and seventeen years after US Marines landed on Oahu and helped coup leaders overthrow the Hawaiian Kingdom, what Sai calls “the myth of Hawaiian statehood” is perpetuated, indeed celebrated, on the third Friday of each August, as Statehood Day.

“America today can no more annex Iraq through a joint resolution than it could acquire Hawaii by joint resolution in 1898. Saddam Hussein’s government, the Baathist party … was annihilated by the United States. But by overthrowing the government, that did not also mean Iraq was overthrown as a sovereign state. Iraq still existed, but it did not have a government,” says Sai.

In his doctoral dissertation, Sai successfully argued that to date, under international laws, Hawaii is in fact not a legal territory of the Unites States, but instead a sovereign kingdom, albeit one lacking its own acting government.

The entity that overthrows a government, Sai says, bears the responsibility to administer the laws of the occupied state.

Sai says that despite what people have been led to believe, the Congressional joint resolution and US failed attempts to annex Hawaii are American laws limited to American territory. He stresses that the executive agreement of 1893 between President Cleveland and Hawaii’s Queen continues to take precedence over any other subsequent actions.

Sai says this all has the potential to completely alter any claims on public or private land ownership, all State of Hawaii government bodies and the presence and activities of the US military in Hawaii, specifically the US Pacific Command (PACOM), the preeminent military authority overseeing operations in the Pacific, Oceania and East Asia.

Among the potential impacts of Sai’s argument is the possibility that the United States’ oldest and arguably most important strategic power center (PACOM’s headquarters are at Camp Smith, near Pearl Harbor) is now facing a legal challenge and occupies territory of questionable legal status.

Sai has presented this information not only in arbitration proceedings at the Permanent Court of Arbitration at the World Court at the Hague and in a complaint filed with the UN Security Council, but in 2001, at the invitation of Lieutenant General James Dubik, before the officer’s corps of the 25th Infantry Division at Schoefield Barracks on Oahu.

After Sai’s presentation before some one hundred officers and their spouses, he says, “You could hear a pin drop. They knew what I was talking about — I didn’t have to say ‘war crimes.'” Sai cited the regulations on the occupation of neutral countries in Hague Convention No. 6.

University of Hawaii Press, which reviewed and approved Sai’s dissertation for publication, indicates Sai’s arguments have “profound legal ramifications.” Sai himself says the case calls into question the legal authority of Senator Daniel Inouye, President Obama and others. After all, both Daniel Inouye and Barack Obama were born in Hawaii which, Sai points out, is not a legal US territory.

On June 1, 2010, Sai advanced his case and filed a lawsuit with the US District Court for the District of Columbia naming Barack H. Obama, Hillary D. R. Clinton, Robert M. Gates, (now former) Governor Linda Lingle and Admiral Robert F. Willard of the US Pacific Command as defendants.

Sai cites the Liliuokalani assignment of executive power as a binding legal agreement which extends from President Cleveland to all successors, including President Obama and his administration, to administer Hawaiian Kingdom law prior to restoring the government.

In the suit, Sai seeks a judgment by the court to declare the 1898 Joint Resolution to provide for annexing the Hawaiian Islands to the United States to be in violation of Hawaiian sovereignty and unconstitutional under US law.

In November, Sai sought to add to the suit as defendants the ambassadors of 35 countries which he says unlawfully maintain consulates in Hawaii in violation of Hawaiian Kingdom law and treaties. These countries include China, India, Russia, Brazil, Australia, Japan and smaller nations like Kiribati, Palau and the tiny enclave of San Marino.

With such a bold case that challenges the very top tier of the United States government and military, it isn’t surprising that not everyone supports Sai’s approach. Some Hawaiian activists privately say Sai’s efforts have the potential to adversely impact other forms of federal recognition such as the Akaka Bill, while others express concerns that such a lawsuit could be at best ineffective and, at worst, result in bad laws.

“In the creation of a society, it’s not only historical justification upon which we need to build Hawaiian sovereignty. We need to bring about better quality of life after independence returns.” – Poka Laenui

Poka Laenui, chairman of the Native Hawaiian Convention, an international delegation of Hawaiians which examines the issues of Hawaiian sovereignty and self-governance, says he does not dispute Sai’s historical claims, nor does he disagree that the US occupies the Hawaiian Islands in violation of international law. He says Sai has made a “very positive contribution.”

He does, however, suggest that Sai’s efforts toward deoccupation could go further or be more inclusive. “I believe what should also be included is decolonization. Along with [Sai’s] analysis, there are many more approaches that are legitimate.”

“Decolonization is a very viable position as well. I’m saying occupation and colonization are on the same spectrum, but colonization goes far deeper. It affects economics, education and value systems like we have in Hawaii today.”

“Hawaii has been squarely named as a country that needs to be decolonized and the US has not followed the appropriate, very clear procedures already set out.” Laenui points out that the United States listed Hawaii as a territory to be decolonized in 1946 in the UN General Assembly Resolution 66 (1).

“We need not only to look at the historical, legal approach, but beyond that … we need to change the deep culture of Hawaii to build a better quality of life,” Laenui says.

Lynette Hiilani Cruz is president of the Ka Lei Maile Alii Hawaiian Civic Club and an assistant professor of anthropology at Hawaii Pacific University. She supports Sai’s efforts and says he provides a “dependable legal basis” for challenging the legality of US claims on Hawaii.

But she also points out there are native Hawaiians who, in spite of the history, are reluctant to associate themselves with the kind of legal challenge Sai is pursuing.

And while some would rather forget historical events, Cruz says, “It is our history, whether you like it or not.” Cruz suggests people visit Sai’s website <hawaiiankingdom.org> and study the original historical documents in order to better understand the basis for Sai’s legal claims.

Dr. Kawika Liu, an inactive attorney with a PhD in politics and a practicing physician, says, “I support many canoes going to the same destination. I’m just a little leery of potentially ending up in a Supreme Court that is extremely hostile to indigenous claims. From my perspective, having litigated a number of native Hawaiian rights cases, I am not sure Sai will make it past procedural matters.”

Liu believes Sai’s characterization of historical and political events is accurate, but says, “You can be very correct in the way you characterize history and still be shot down because of issues of jurisdiction.”

“We’re operating in the courts of the colonizer … and they have their own agenda, which is, to me, reinforcing US hegemony.”

Liu sees the greatest benefit of Sai’s work as raising awareness of the issue. “I think the more awareness that’s raised – eventually the change is going to come.”

One academic who thinks Sai is on the right track is Dr. Jon Kamakawiwoole Osorio, professor of Hawaiian studies at the University of Hawaii. Osorio specializes in the politics of identity in the Hawaiian Kingdom and the colonization of the Pacific and served on Sai’s dissertation committee.

He says Sai knows international law and the laws of occupation as they pertain to Hawaii as well as any academic in Hawaii today.

Yet he recognizes Sai has detractors – those who feel that any kind of interpretation which exalts Western law does a disservice to native people and institutions which thrived without those laws for millennia. Osorio also says that while arguing that Hawaii has a solid international case sounds really good, it doesn’t go very far if the US government simply refuses to acknowledge that case or respond in any way.

So does Osorio think Sai’s efforts are counterproductive or a waste of time?

“I don’t think that’s the case,” Osorio says. “I think most people believe Keanu Sai has really added a tremendous new perspective of the kingdom, lawmaking and the creation of constitutional law in Hawaii.”

He also believes Sai’s argument that sovereignty, once conferred, doesn’t disappear just because it is occupied by another country.

What Sai may be pursuing, Osorio suggests, is to push for a definitive stance by the US government which may take the form of a denial that Hawaiians can claim sovereignty.

“I think Sai’s attempt to push the US, to corner it and force it to acknowledge that it holds Hawaii only by raw power … is an important revelation that would have really important political ramifications.”

“Sai says our sovereignty is still intact. That has been a tremendous gift for the Hawaiian movement because it keeps many of us pursuing independence from the United States instead of simply settling for some other kind of status (such as the Akaka Bill) because we feel like we aren’t legally entitled to it,” Osorio says.

“The violence done against the Hawaiian kingdom at the end of the [19th] century was no less violent just because not a lot of people were killed,” Osorio says. “It violated our laws, it violated our trust, it violated the relationship between our people and our rulers and it continues to this day to stand between any kind of friendly relations between Hawaiians who know this history and the United States.

“Sai’s analysis helped many of us to understand more completely that we don’t have to think of ourselves as Americans — ever.”

Ho‘i I Ka Piko: Island Wide Solstice Prayer for Mauna Kea

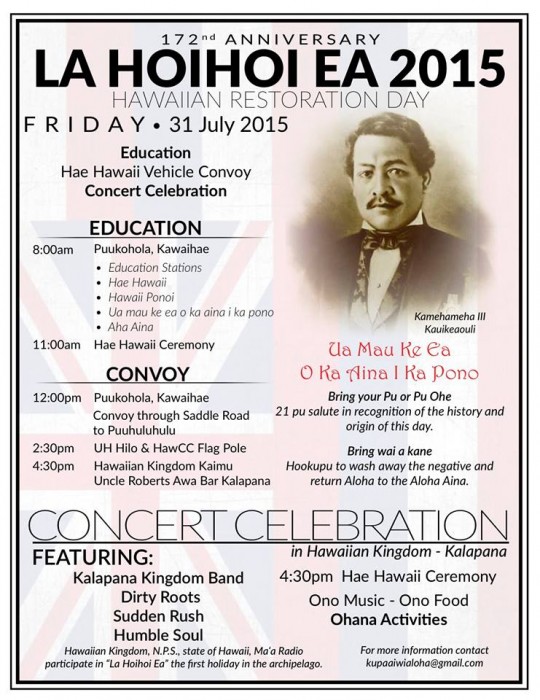

Hawai‘i Island: La Ho‘iho‘i Ea (Restoration Day) Celebration

In the summer of 1842, Kamehameha III moved forward to secure the position of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a recognized independent state under international law. He sought the formal recognition of Hawaiian independence from the three naval powers of the world at the time—Great Britain, France, and the United States. To accomplish this, Kamehameha III commissioned three envoys, Timoteo Ha‘alilio, William Richards, who at the time was still an American Citizen, and Sir George Simpson, a British subject. Of all three powers, it was the British that had a legal claim over the Hawaiian Islands through cession by Kamehameha I, but for political reasons the British could not openly exert its claim over the other two naval powers. Due to the islands prime economic and strategic location in the middle of the north Pacific, the political interest of all three powers was to ensure that none would have a greater interest than the other. This caused Kamehameha III “considerable embarrassment in managing his foreign relations, and…awakened the very strong desire that his Kingdom shall be formally acknowledged by the civilized nations of the world as a sovereign and independent State.”

In the summer of 1842, Kamehameha III moved forward to secure the position of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a recognized independent state under international law. He sought the formal recognition of Hawaiian independence from the three naval powers of the world at the time—Great Britain, France, and the United States. To accomplish this, Kamehameha III commissioned three envoys, Timoteo Ha‘alilio, William Richards, who at the time was still an American Citizen, and Sir George Simpson, a British subject. Of all three powers, it was the British that had a legal claim over the Hawaiian Islands through cession by Kamehameha I, but for political reasons the British could not openly exert its claim over the other two naval powers. Due to the islands prime economic and strategic location in the middle of the north Pacific, the political interest of all three powers was to ensure that none would have a greater interest than the other. This caused Kamehameha III “considerable embarrassment in managing his foreign relations, and…awakened the very strong desire that his Kingdom shall be formally acknowledged by the civilized nations of the world as a sovereign and independent State.”

While the envoys were on their diplomatic mission, a British Naval ship, HBMS Carysfort, under the command of Lord Paulet, entered Honolulu harbor on February 10, 1843, making outrageous demands on the Hawaiian government. Basing his actions on complaints made to him in letters from the British Consul, Richard Charlton, who was absent from the kingdom at the time, Paulet eventually seized control of the Hawaiian government on February 25, 1843, after threatening to level Honolulu with cannon fire. Kamehameha III was forced to surrender the kingdom, but did so under written protest and pending the outcome of the mission of his diplomats in Europe. News

While the envoys were on their diplomatic mission, a British Naval ship, HBMS Carysfort, under the command of Lord Paulet, entered Honolulu harbor on February 10, 1843, making outrageous demands on the Hawaiian government. Basing his actions on complaints made to him in letters from the British Consul, Richard Charlton, who was absent from the kingdom at the time, Paulet eventually seized control of the Hawaiian government on February 25, 1843, after threatening to level Honolulu with cannon fire. Kamehameha III was forced to surrender the kingdom, but did so under written protest and pending the outcome of the mission of his diplomats in Europe. News  of Paulet’s action reached Admiral Richard Thomas of the British Admiralty, and he sailed from the Chilean port of Valparaiso and arrived in the islands on July 25, 1843. After a meeting with Kamehameha III, Admiral Thomas determined that Charlton’s complaints did not warrant a British takeover and ordered the restoration of the Hawaiian government, which took place in a grand ceremony on July 31, 1843. At a thanksgiving service after the ceremony, Kamehameha III proclaimed before a large crowd, ua mau ke ea o ka ‘aina i ka pono (the life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness). The King’s statement became the national motto.

of Paulet’s action reached Admiral Richard Thomas of the British Admiralty, and he sailed from the Chilean port of Valparaiso and arrived in the islands on July 25, 1843. After a meeting with Kamehameha III, Admiral Thomas determined that Charlton’s complaints did not warrant a British takeover and ordered the restoration of the Hawaiian government, which took place in a grand ceremony on July 31, 1843. At a thanksgiving service after the ceremony, Kamehameha III proclaimed before a large crowd, ua mau ke ea o ka ‘aina i ka pono (the life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness). The King’s statement became the national motto.

The envoys eventually succeeded in getting formal international recognition of the Hawaiian Islands “as a sovereign and independent State.” Great Britain and France formally recognized Hawaiian sovereignty on November 28, 1843 by joint proclamation at the Court of London, and the United States followed on July 6, 1844 by a letter of Secretary of State John C. Calhoun. The Hawaiian Islands became the first Polynesian nation to be recognized as an independent and sovereign State.

The ceremony that took place on July 31 occurred at a place we know today as “Thomas Square” park, which honors Admiral Thomas, and the roads that run along Thomas Square today are “Beretania,” which is Hawaiian for “Britain,” and “Victoria,” in honor of Queen Victoria who was the reigning British Monarch at the time the restoration of the government and recognition of Hawaiian independence took place.