To go to ABC News Australia coverage click here.

Author Archives: Hawaiian Kingdom

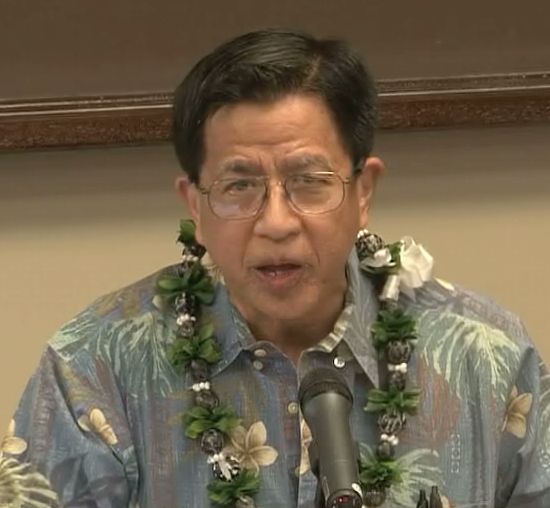

State of Hawai‘i Hawaiian Homes Commissioner “Uncle Joe” Tassil Calls for Moratorium on all Evictions in Hawaiian Homes because of War Crimes

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE:

HAWAIIAN HOMES COMMISSIONER “UNCLE JOE” TASSIL CALLS FOR MORATORIUM ON ALL EVICTIONS IN HAWAIIAN HOMES

9/22/2014

At Hawaiian Homes hearing at Paukukalo 10:00 a.m. this morning, “Uncle Joe” Tassil called for a moratorium of all evictions in Hawaiian Homes until the Justice Department responds to a letter authored by Dr. Chang, Professor of Law at UH which letter was premised upon a letter and memorandum drafted by Dr. Keanu Sai, Ph.D. regarding the current existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the unlawful occupation by the United States in Hawai’i. Attorney Dexter Kaiama testified on behalf of qualified Hawaiian Beneficiaries as to Department of Hawaiian Homelands, a state agency’s, lack of jurisdiction. Christopher Fishkin, a legal assistant to a law office in Wailuku, testified separately, to numerous violations of Federal law by DHHL and violations of the rights of qualified Hawaiian beneficiaries pursuant to the Federal law. Fishkin also encouraged the Commissioners to adopt Commissioner Tassil’s recommendation of a moratorium of evictions, to review and address the violations of Hawaiians’ rights in Hawaiian Homes which Fishkin asserted were being perpetuated against qualified Hawaiian beneficiaries under the color of state law.

At Hawaiian Homes hearing at Paukukalo 10:00 a.m. this morning, “Uncle Joe” Tassil called for a moratorium of all evictions in Hawaiian Homes until the Justice Department responds to a letter authored by Dr. Chang, Professor of Law at UH which letter was premised upon a letter and memorandum drafted by Dr. Keanu Sai, Ph.D. regarding the current existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the unlawful occupation by the United States in Hawai’i. Attorney Dexter Kaiama testified on behalf of qualified Hawaiian Beneficiaries as to Department of Hawaiian Homelands, a state agency’s, lack of jurisdiction. Christopher Fishkin, a legal assistant to a law office in Wailuku, testified separately, to numerous violations of Federal law by DHHL and violations of the rights of qualified Hawaiian beneficiaries pursuant to the Federal law. Fishkin also encouraged the Commissioners to adopt Commissioner Tassil’s recommendation of a moratorium of evictions, to review and address the violations of Hawaiians’ rights in Hawaiian Homes which Fishkin asserted were being perpetuated against qualified Hawaiian beneficiaries under the color of state law.

Representative of Habitat for Humanity and solar energy providers to Hawaiian Homes testified as to lengthy delays in their being able to provide services to Hawaiians in Hawaiian Homes and unclear contractual obligations in order to do so.

Contact Commissioner Joe Tassil for more info. 808-664-6901

Aloha ‘Aina Talk Story with Associate Professor Kaleikoa Ka‘eo

https://vimeo.com/106904451

A very provocative talk story session with Associate Professor Kaleikoa Kaeo of the University of Hawai‘i Maui College and Keala Kelly about Hawaiian Consciousness and being Enlightened. This is part 1 of 2.

Press Conference of Professor Williamson Chang at the University of Hawai‘i Law School

Click here to download Professor Chang’s prepared statement read at the press conference.

Kingdom Media Hawai‘i Live Stream of Professor Chang’s Press Conference

Kingdom Media Hawai‘i will be providing a live stream of Professor Chang’s press conference at the University of Hawai‘i William S. Richardson School of Law. The press conference will begin at 2:00 pm in front of the Law School’s administration building across from the Law Library.

UPDATE: Due to technical difficulties the live streaming was not able to take place. Kingdom Media Hawai‘i, however, did record the press conference and will be playing it on its website.

https://vimeo.com/107008784

Senior Law Professor Reports War Crimes to U.S. Attorney General

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Press Conference at William S. Richardson School of Law, University of Hawai‘i at Manoa, Monday, September 22, 2014, at 2:00 pm

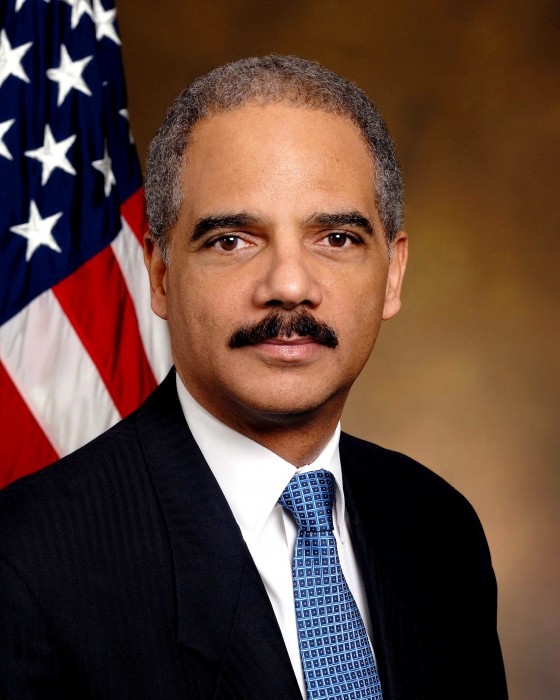

University of Hawai‘i’s senior law professor notifies U.S. Attorney General, Eric Holder, Jr., of war crimes committed in the Hawaiian Islands

HONOLULU (September 19, 2014) – Senior law professor Williamson B.C. Chang has reported to U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder, Jr. that war crimes have and continue to be committed in the Hawaiian Islands. Professor Chang is a faculty member of the University of Hawai‘i William S. Richardson School of Law and has been with the law school for the past thirty-eight years.

HONOLULU (September 19, 2014) – Senior law professor Williamson B.C. Chang has reported to U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder, Jr. that war crimes have and continue to be committed in the Hawaiian Islands. Professor Chang is a faculty member of the University of Hawai‘i William S. Richardson School of Law and has been with the law school for the past thirty-eight years.

The Office of Hawaiian Affairs’ (OHA) top executive, CEO Kamanaopono Crabbe, contracted political scientist, Dr. Keanu Sai, to draft a memorandum on the legal status of Hawai‘i under international law. Based on information Sai disclosed in what has become known as the OHA Memo, CEO Crabbe authored a letter to Secretary of State, John Kerry. Crabbe sought legal clarification on the status of Hawai‘i from Secretary Kerry primarily because Sai concluded that OHA is in possession of monies acquired from the “State of Hawai‘i’s” general fund through pillaging.

Pillaging is prohibited under article 33 of the 1949 Geneva Convention, IV, being a war crime under U.S. federal criminal law as well as a felony. According to 18 U.S.C. §2441 “Whoever, whether inside or outside the United States, commits a war crime…shall be fined under the this title or imprisoned for life or any number of years, or both, and if death results to the victim, shall also be subject to the penalty of death.”

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia has defined pillaging, which is the same as plunder, as “the fraudulent appropriation of public and private funds belonging to…the opposing party.” According to the OHA Memo, the State of Hawai‘i is not a legitimate government under international law and as a self-declared entity it has no authority to collect taxes from individuals throughout the Hawaiian Islands. This fraudulent collection of monies is a form of pillaging from public property that belongs to the Hawaiian Kingdom, not the United States.

In the letter addressed to Attorney General Holder, Professor Chang described his reporting of war crimes as being obligated under Federal criminal law and if he did not report the war crimes he could be fined or imprisoned for three years. “Pursuant to 18 U.S.C. §4—Misprision of felony, I am legally obligated to report to you the knowledge I have about multiple felonies that prima facie have been and continue to be committed here in the Hawaiian Islands,” Chang said. “I have been made aware of these felonies through the memorandum by political scientist David Keanu Sai, Ph.D., who was contracted by the State of Hawai‘i Office of Hawaiian Affairs, entitled Memorandum for Ka Pouhana, CEO of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs regarding Hawai‘i as an Independent State and the Impacts it has on the Office of Hawaiian Affairs.”

In the letter addressed to Attorney General Holder, Professor Chang described his reporting of war crimes as being obligated under Federal criminal law and if he did not report the war crimes he could be fined or imprisoned for three years. “Pursuant to 18 U.S.C. §4—Misprision of felony, I am legally obligated to report to you the knowledge I have about multiple felonies that prima facie have been and continue to be committed here in the Hawaiian Islands,” Chang said. “I have been made aware of these felonies through the memorandum by political scientist David Keanu Sai, Ph.D., who was contracted by the State of Hawai‘i Office of Hawaiian Affairs, entitled Memorandum for Ka Pouhana, CEO of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs regarding Hawai‘i as an Independent State and the Impacts it has on the Office of Hawaiian Affairs.”

Chang explained the action taken was not only prompted by a legal obligation, but also because he’s a State of Hawai‘i employee. “I and other State officials and employees receive State monies that have been implicated as being gained through the commission of felonies, namely the war crime of pillaging, and we could also face prosecution under 18 U.S.C. §3—Accessory after the fact,” Chang said. “I am deeply concerned about this matter that affects all State of Hawai‘i officials and employees, including myself personally.”

Due to the urgency of the matter Chang’s letter asks for a response from the Department of Justice within two weeks. If the Department of Justice’s “response in two weeks is able to refute the evidence provided for in the Memo, then assuredly the felonies—war crimes—have not been committed,” Chang said. The letter goes on to say, “But if your office is not able to refute the evidence, then this is a matter for the U.S. Pacific Command, being the occupying power, and all State of Hawai‘i officials and employees, as well as I, are compelled to comply with Hawaiian Kingdom law and the law of occupation.”

Chang’s letter was also carbon copied to the Commander of the U.S. Pacific Command headquartered at Camp Smith, Island of O‘ahu, and to the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court in The Hague, Netherlands.

The press conference will be located in front of the Administration building across from the Law Library. Parking is provided in the parking structure behind the law school at $5.00.

Joining Professor Chang at Monday’s press conference will be some of the 17 State of Hawaii employees from the University of Hawaii, the Department of Human Services, the Department of Public Safety, the Maui Fire Department, and the Department of Hawaiian Homelands, who endorsed the letter. Dr. Sai will also be at the press conference.

Click here to download Professor Chang’s letter.

Click here to download the OHA Memo.

Hawaiian Gazette Reports Americanization Program for Schools in Hawai‘i

On April 3, 1906, the Hawaiian Gazette reported on page 6:

“As a means of inculcating patriotism in the schools, the Board of Education has agreed upon a plan of patriotic observance to be followed in the celebration of notable days in American history, this plan being a composite drawn from the several submitted by teachers in the department for the consideration of the Board. It will be remembered that at the time of the celebration of the birthday of Benjamin Franklin, an agitation was begun looking to a better observance of these notable national holidays in the schools, as tending to inculcate patriotism in a school population that needed that kind of teaching, perhaps, more than the mainland children do–although patriotism is inculcated in the schools there, also.

The matter was taken up by the school department, at once, and the teachers were asked to submit their views upon it. The result is embodied in the “patriotic program” printed herewith, which represents the best educational thought of the Territory. The program follows, and will be sent out officially in pamphlet form as a guide to teachers in the observance of national days in the schools.”

The term “inculcate” is defined as “to cause something to be learned by someone by repeating it again and again.” This is another word for “indoctrination” that is defined as “the process of inculcating ideas, attitudes, cognitive strategies or a professional methodology (see doctrine). It is often distinguished from education by the fact that the indoctrinated person is expected not to question or critically examine the doctrine they have learned.”

To download the full article click here.

To download the Patriotic Program pamphlet click here.

According to the U.S. Library of Congress’ “Chronicling America“:

“The Hawaiian Gazette was a fervent advocate of the sugar industry and other American economic interests in Hawai‘i. Early on, these interests were in line with those of the Hawaiian monarchy; as such, the Hawaiian Gazette became the official newspaper of the Kingdom in 1865 under King Kamehameha V and was published by James H. Black and the Hawaiian government until 1873. In the mid-1870s, the paper turned decidedly anti-monarchy when the views of King Kalākaua and those of the local oligarchy–a powerful contingent of pro-American, pro-annexation sugar interests–began to diverge. The Hawaiian Gazette attacked Kalākaua’s government for what it regarded as wasteful spending on the King’s coronation ceremony and efforts to revive public performances of Hawaiian chanting and hula. It avidly supported the call for a new government, which was achieved in 1887 when the Bayonet Constitution effectively stripped the king of his power and secured the oligarchy’s political authority. At that time, the Hawaiian Gazette resumed its place as one of the government’s biggest advocates; indeed, several high-ranking members of the oligarchy, including William R. Castle and Sanford B. Dole, would oversee the newspaper in years to come. In January 1893, the paper was among several that refused to print Queen Liliu‘okalani’s protest against the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy and painted her efforts to reestablish the Kingdom’s authority as illegal and counterrevolutionary. Following the Queen’s overthrow on January 17, 1893, the Hawaiian Gazette published the proclamation and orders of the new Provisional Government and began referring to Liliu‘okalani as Hawai‘i’s ‘ex-Queen.’ Two weeks later, the paper asserted that it, together with the Pacific Commercial Advertiser , “contained the only true and extended account of the late revolution”and encouraged readers to sign the Provisional Government’s loyalty oath.”

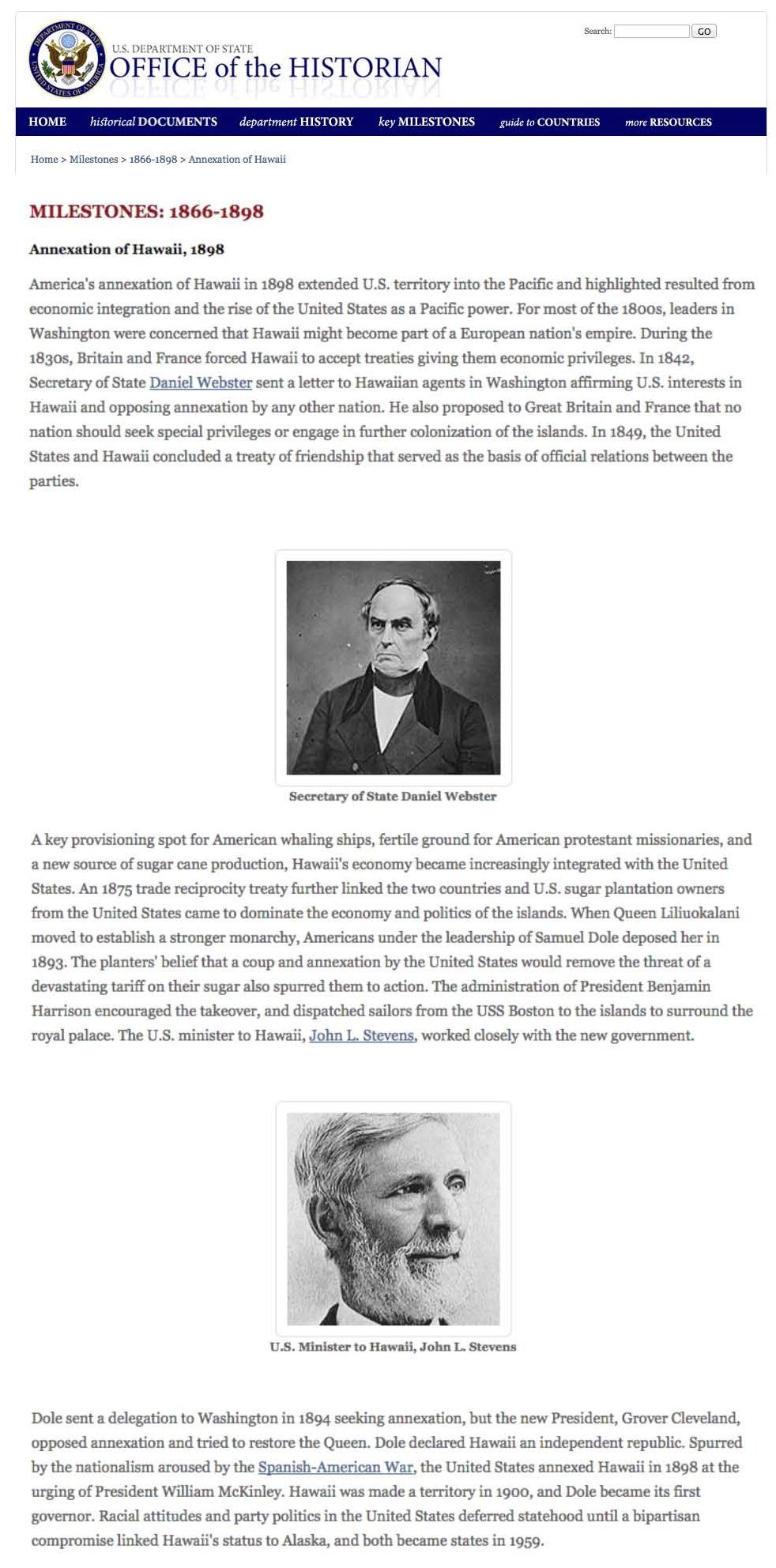

U.S. Department of State’s Website: Article on Hawaiian Annexation Removed

In an interesting move by the Office of the Historian on the U.S. Department of State, the article Annexation of Hawai‘i, 1898, was “removed pending review to ensure it meets our standards for accuracy and clarity.”

Below is the article that was removed.

Aloha ‘Aina Talk Story with Professor Chang

https://vimeo.com/105856766

To download Professor Chang’s testimony to the Department of Interior when they held public hearings throughout the Hawaiian Islands click here.

Aloha ‘Aina Talk Story with Professor Chang

https://vimeo.com/105883715

A follow up to the September 2nd Panel Discussion Hosted by The American Constitutional Society with Professor Williamson Chang and Anne Keala Kelly. This is a part 1 of 2 episodes and will surely keep you intrigued…

Life in the Law – Interview with Professor Williamson Chang and Dr. Keanu Sai

Host of Life in the Law, Kenneth Lawson, interviews law Professor Williamson Chang and political scientist Dr. Keanu Sai on the legal issues surrounding the occupation of the Hawaiian Islands. Lawson is faculty at the University of Hawai‘i William S. Richardson School of Law and teaches criminal law.

Resistance Radio – Interview with Film Maker Anne Keala Kelly

Anne Keala Kelly is an award winning, Native Hawaiian filmmaker and journalist whose works focus primarily on the early 21st century Hawaiian sovereignty movement. Her feature length documentary, Noho Hewa, has been screened and broadcast internationally and is widely taught in university courses that focus on indigenous peoples, the Pacific, and colonization.

Anne Keala Kelly is an award winning, Native Hawaiian filmmaker and journalist whose works focus primarily on the early 21st century Hawaiian sovereignty movement. Her feature length documentary, Noho Hewa, has been screened and broadcast internationally and is widely taught in university courses that focus on indigenous peoples, the Pacific, and colonization.

AKAKU presents: A talk with Dr. Keanu Sai from the island of Molokai – August 20th, 2014

https://vimeo.com/105051916