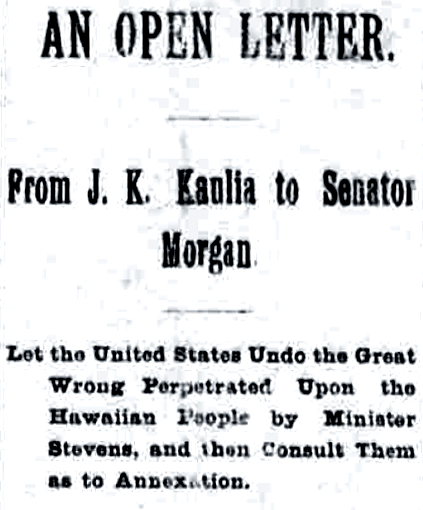

There is cause for congratulating ourselves, we who have yet faith in the justice and honor of the great United States, our greatest friend and nearest neighbor, at the presence in our midst of that noble representative of the Senate of the United States Hon. John T. Morgan, of Alabama. The Senator comes not hither unknown, unhonored or unsung, for thousands have heard his voice, only a few weeks ago in the Capital City of California, and tributes of esteem have met him at every turn. To those who have no knowledge of Senator Morgan’s character or position it was sufficient to say that the gentleman is Chairman of the Committee on Foreign Relations of the United States Senate, a Committee which will, in the near future, pass upon questions of grave importance to little Hawaii, and the result of which means an honorable life as an independent nation or the sending out of national existence the only representative nation in the Pacific. Senator Perkins, a long time friend of Senator Morgan, says: “if there is one that ever occupied the position of a Senator with a conscientious desire to do his duty faithfully to the whole people, it is the distinguished Senator from Alabama.” And the words that Senator Morgan given public voice to, before leaving the City of San Francisco, shows his mission hither; he says, “I am going as far as the Hawaiian Islands for the purpose of trying to understand the geographical, commercial and other situations which I conceive to be very important for the people and the Government of the United States and (mark) necessary to enable me to conscientiously discharge duties incumbent on me and my colleagues in the House and the Senate.”

There is cause for congratulating ourselves, we who have yet faith in the justice and honor of the great United States, our greatest friend and nearest neighbor, at the presence in our midst of that noble representative of the Senate of the United States Hon. John T. Morgan, of Alabama. The Senator comes not hither unknown, unhonored or unsung, for thousands have heard his voice, only a few weeks ago in the Capital City of California, and tributes of esteem have met him at every turn. To those who have no knowledge of Senator Morgan’s character or position it was sufficient to say that the gentleman is Chairman of the Committee on Foreign Relations of the United States Senate, a Committee which will, in the near future, pass upon questions of grave importance to little Hawaii, and the result of which means an honorable life as an independent nation or the sending out of national existence the only representative nation in the Pacific. Senator Perkins, a long time friend of Senator Morgan, says: “if there is one that ever occupied the position of a Senator with a conscientious desire to do his duty faithfully to the whole people, it is the distinguished Senator from Alabama.” And the words that Senator Morgan given public voice to, before leaving the City of San Francisco, shows his mission hither; he says, “I am going as far as the Hawaiian Islands for the purpose of trying to understand the geographical, commercial and other situations which I conceive to be very important for the people and the Government of the United States and (mark) necessary to enable me to conscientiously discharge duties incumbent on me and my colleagues in the House and the Senate.”

Again, later on, in the speech delivered by him in San Francisco on the evening of tho 6th of September, Senator Morgan gave expression to sentiments which do honor to his heart and head and enables one to place great confidence in this leading American Senator for he said: “I think that an American citizen who is an honest man faithful to his duties and who has a trust reposed in him by the voice of a constituency when he pursues that cause unfalteringly, honestly, impartially and justly is entitled to the encomium at least of ‘Well done thou good and faithful servant.’ When we come to the end of our earthly career, if a higher power shall say to each and all of us, ‘Well done thou good and faithful servant,’ we will feel that we have not insufficiently served the Master who can bestow on us benedictions like that.” To us here in Hawaii, who still love Hawaii and hope for the long-delayed but expected justice at the hands of the United States, Senator Morgan voicing such sentiments, would prove a good advocate when time and opportunity makes him familiar with the surroundings of the coup d’etat which caused Hawaii to be the petitioner to her great and good friend, “Uncle Sam,” to have right and justice done her.

To ask for bread and receive but a stone would hardly be provocative of obtaining the praise and blessing of the Just One so aptly alluded to by Senator Morgan. And, Senator Morgan coming here, as he does, on an honest survey, 2,100 miles across the blue Pacific, shut off for several weeks from his people, came not alone but in company of other distinguished members of the Congress of the United States. But why should those distinguished people come so far? when, as Senator Morgan truly says, “The United States Government, great, majestic, powerful and splendid as it is, is still in its formative period. We are not yet a complete Government.” True, Senator, such has been said before and will be again, and as you yourself say, Mr. Senator, “Look at Alaska, that vast body of land which is developing more wealth, both in the supply of human food from the sea and gold from the land, and timber. Look at it. It has not yet a Governor. It has no Legislature; it has a mere form of a judicial system. New Mexico and Arizona are yet under a territorial Government.” But, is it because the goods are of better quality in Hawaii and practically unprotected that the desire for attainment becomes so prominent to-day. The destiny of Hawaii, situated in the Mid-Pacific as she is, should be that of an independent nation and so she would be were it not for the policy of greed which pervades the American Legislators and the spirit of cowardice which is in the breasts of those who first consummated the theft of Hawaiian prestige.

But from Senator Morgan, we hope for bettor results than might be expected when he already has mapped out that the boundary line, The “outside boundary of the United States is to begin at the island of Pioka, 600 miles west of Honolulu, in the Aleutian Peninsula, and swooping from there to the Hawaiian group, then to the land 12 miles below San Diego on the Mexican border.” But “man proposes and God disposes,” and the Senator, who was a sturdy champion of the cause of succession when it threatened to disrupt that great country of his which he now speaks of so fervently, the Senator knows that the ways of Providence are inscrutable and God defends the right.

Again it seems as though it were a great waste of time and labor for Senator Morgan to leave the shores of California when there is so much there to be done in throttling the gigantic steals which are, as he states he has knowledge of, being perpetrated on the United States Government and the people of California. The Senator states that there is now an attempt being made to steal $25,000,000, and that there is “need for the people of California to take immediate action.” In the next few words the Senator tells those same people, American citizens, and members of that “majestic and splendid Government,” that this great wrong that he speaks of is about being carried out in his own grand country (to which he seeks to annex yet virtuous little Hawaii), this monstrous steal of which the honorable gentleman facetiously remarks that 25,000,000 was taken “for pocket lining,” this wrong is being consummated, and will be consummated, and before Congress meets in next December, * * * we will then have presented to us the judgment of a court upon a great case, and you and I, sir, will be asked to swallow it,” and the Senator plainly tells them that they, the people, are practically helpless in a matter of this kind.”

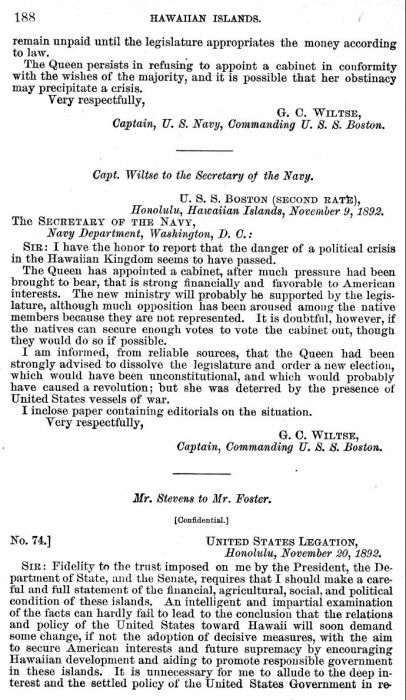

But let us here in Hawaii aid the Senator in his excursion of some 6000 miles for knowledge on a question which he pleads lack of information although it seems that the name of the Senator has become attached to at least one official brochure which loomed with thoughts upon Hawaii and the annexation to the United States of America. The logical way to debate this question, Mr. Senator Morgan, would be, first, to prove that the United States has a right to annex these islands, for if the coveted territory were a gold mine of inestimable value, if annexation be an unjust act, the United States should positively refuse to add the Hawaiian Islands to her territory, and Senator Morgan, an honorable representative of that great Government, anxious to do his duty conscientiously, with the seeming love for God in his heart and the desire for the approbation of being “a good and faithful servant” on his lips, should be last man to aid, over so little, in the consummation of a wrong. Then let us reason together, Mr. Senator, on the justice of the question. It cannot be foreign to your knowledge, sir, that, in dispatch numbered 74 of ex-American Minister Stevens, that gentleman previous to the so-called revolution of January 16, 1893, published the fact that he was engaged with certain American citizens to overthrow the Hawaiian Government. In this dispatch sent to Washington some fifty days before the revolution, the then American Minister asks for “wise and bold action” to overthrow the monarchy and rescue the property owners.

Can the United States in consistency with past principles annex these islands until she has made herself right before the world by undoing everything that this Minister has done? Can the United States afford to have annexation of the Hawaiian Islands go down into history as having been previously worked up by the United States Minister and American citizens? And let us see fully the hand that the American Minister had in the overthrow of a friendly sovereign. After the Queen had withdrawn the proposed Constitution after an official proclamation had been issued congratulatory on the peace and order which had prevailed, when the usual routine of business and pleasure was again at work, and the Hawaiians had settled down again to their usual quiet life, when no riot had occurred nor no life been lost, Mr. Stevens, the American Minister, writes to Captain Wiltze, commanding the U. S. S. Boston, then in Honolulu Harbor:

“Sir.—In view of the existing critical circumstances in Honolulu, including an inadequate legal force I request you to land marines and sailors from the ship under your command for the protection of the United States Legation and the United States Consulate, and to secure the safety of American life and property.”

Now, Mr. Senator Morgan, where, think you, were the “critical circumstances?” Not in the Government, nor among the Hawaiians. No. The “critical circumstances” were a little knot of foreigners (Americans) trying to overthrow the Constitutional Government so that they could offer the Hawaiian Islands to the United States for annexation, and at the time they did not have a single soldier in arms. It was “critical circumstances” indeed. The Queen with her one thousand or more determined men could have destroyed the conspiracy quickly, but Mr, Stevens, the American Minister, landed the United States troops and held the Queen and the army at bay until the conspirators had organized to overthrow the Government. When the then United States representative (Mr. Blount) arrived here some thirty days after the Provisional Government, which was offering itself and its stolen property to the United States, was still under the protection of Mr. Stevens and the army and navy of America. And Mr. Senator Morgan let me draw your attention to the fact that the Queen did not surrender to the Provisional Government but to the United States and declared in a published statement that, “I yield to the superior force of the United States.” En passant it may be worthy your attention that the protest of Her Majesty to her great and good friend Uncle Sam yet remains unanswered.

Now, Mr. Senator, let us place this state of things as happening in America and at a time, Mr. Senator when you had knowledge from personal experience, of the surrounding circumstances. Let us suppose that at the time the people of the South were working up their great conspiracy to divide the Union that a large Union army was in readiness to squelch the conspiracy. Suppose at this time England with a much larger and stronger army had landed and marched between the forces of the North and South and had held the people of the North at bay until the South had so organized their forces as to be enabled to overthrow the Government! England would have been just as guilty and responsible as if she had taken the American Capital by storm. Do you not think so, Mr. Senator?

But let us consider the position of the United States if this proposed scheme of annexation is consummated. By such act the established policy of the United States is at once broken and the change of national policy is a grave proceeding, it involves the fate of the nation that changes it. The complex territorial interests both at home and abroad of the European powers has forced upon those powers relations of a most intricate character. Territory is the bone of their contention. Intervention is the policy of European nations but it is not the policy of the United States. Instead of being surrounded by rivals, America lives in a sphere essentially her own. No armies or navies are needed to preserve a “Balance of Power,” for there is none to preserve. She is so far distant from the complications of the other great nations that to her it matters not whether the star ascendant of Europe be that of England, France, Germany, Russia or Austria. Her territorial isolation has enabled her to pursue an isolated policy, a policy of “Friendship with all nations and entangling alliances with none” has been the motto of all administrations from Washington on.

The American people delivered from the desire and fear of war sentiments, from standing armies and great navies have been free to take the leading place in this world’s industrial development. But a change of conditions must bring a change of policy. The ocean territories are largely in the possession of other powers; an extension of American domain into the same regions means an identification of American foreign interests with other powers and the consequent entanglement and complications which American policy has always sought to avoid. And why this greed for the Hawaiian Islands? Is it a naval station that is needed? For that it would seem that American home ports are much in need of such protection. Is it a coaling station that is desired? That is obtainable by treaty. Or is it the islands’ wealth that America desires? If so, then America will desire to annex the earth. The shore lines of American policy once crossed is crossed for ever and one acquisition leads but to another. And Mr. Senator, let me say in closing that, annexation or no annexation “Fiat justitia ruat cœlum;” there is a preferred charged of wrong-doing and justice against the United States, let there not be another and graver one of direct subjugation. Ask for the voice of Hawaii on this subject Mr. Senator, and you will hear it with no uncertain tones ring out from Niihau to Hawaii—”Independence now and forever.”

Then Mr. Senator, let The Great Republic of America undo the wrong that has been done to the Hawaiian Nation by its Representatives, and when you come to the end of your earthly career a High Power will say “Well done thou good and faithful Servant.”

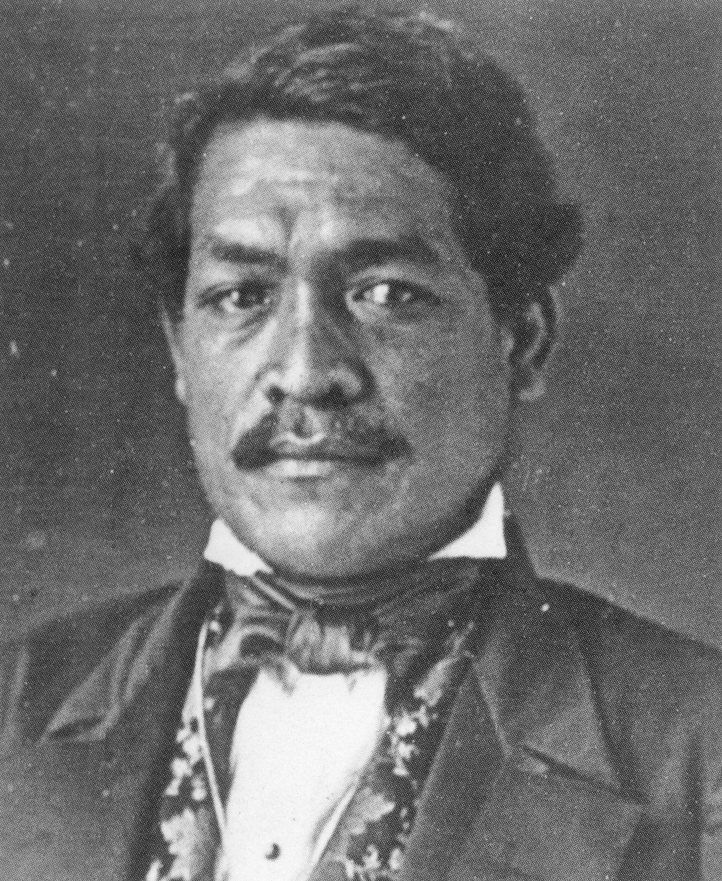

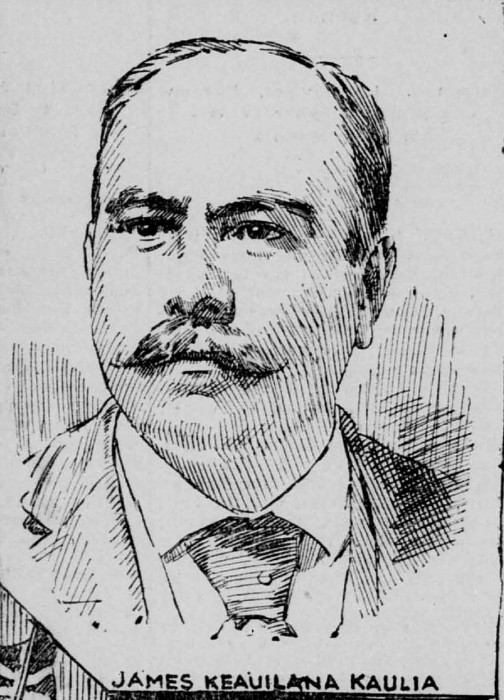

James Keauiluna Kaulia.

Honolulu, Oct. 11, 1897.

Professor Williamson Chang was born and raised in Honolulu, Hawai‘i. He graduated from Princeton University with degrees in Asian Studies and from the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. Thereafter, he attended the University of California, Berkeley [Boalt Hall] where he was an editor of both the California Law Review and the Ecology Law Quarterly. He clerked for U.S. District Court Judge Dick Yin Wong in Honolulu and began teaching at the University of Hawai`i the following year.

Professor Williamson Chang was born and raised in Honolulu, Hawai‘i. He graduated from Princeton University with degrees in Asian Studies and from the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. Thereafter, he attended the University of California, Berkeley [Boalt Hall] where he was an editor of both the California Law Review and the Ecology Law Quarterly. He clerked for U.S. District Court Judge Dick Yin Wong in Honolulu and began teaching at the University of Hawai`i the following year.