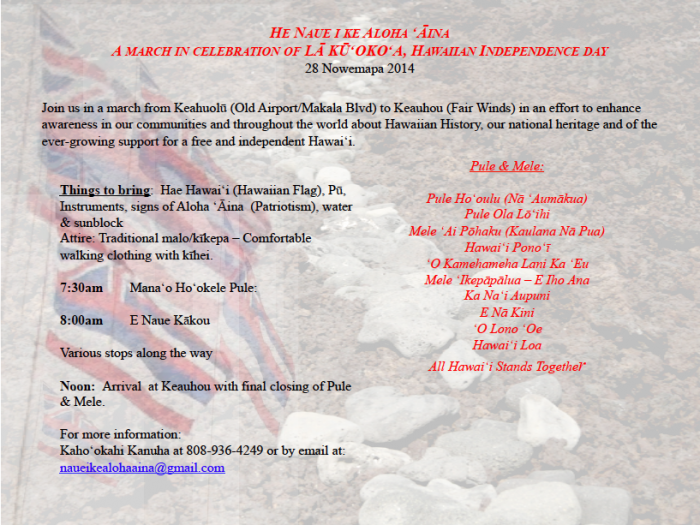

A March in Celebration of Lā Kūʻokoʻa, Hawaiian Independence Day

Hōlualoa, Kona, Hawaiʻi

For Immediate Release

November 12, 2014

NAUE I KE ALOHA ʻĀINA!

A march in celebration of Lā Kūʻokoʻa, Hawaiian Independence Day

November 28, 2014

8:00am

Old Airport to Keauhou Small Boat Harbor

Hawaiians and supporters across the islands will march on Lā Kūʻokoʻa (Hawaiian Independence Day) on Friday November 28, 2014 in an effort to enhance awareness in our communities and throughout the world about one of the longest standing National Holidays of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi. Marchers will gather at the Old Kona Airport across from Makala Blvd at 7:30am for opening thoughts and pule. The march will begin at 8:00am and will cover approximately eight miles starting from the Old Airport in the ahupuaʻa of Keahuolū and ending in the ahupuaʻa of Keauhou at the birth site of Kauikeaouli (Kamehameha III).

In Hawaiian, naue means to march. It also means to move, to shake, to tremble, to vibrate and to quake, as the earth. Aloha ʻāina means love of oneʻs land or of oneʻs country. It means patriot, a patriot who illustrates a deep love for the land. On this day of national independence, we hope that our lāhui will naue. That is, this march is meant to illustrate a true and deep love that will shake, vibrate, tremble and move our land and people towards our true patriotism.

“This is a march of aloha. This is a march of love for our land and love for our country. We march together as one with the hope that our claim to national independence may be seen and heard by our local communities and throughout the world. Aloha ʻ āina is alive and it will never die,” says Hawaiian medium preschool teacher and march organizer, Kahoʻokahi Kanuha.

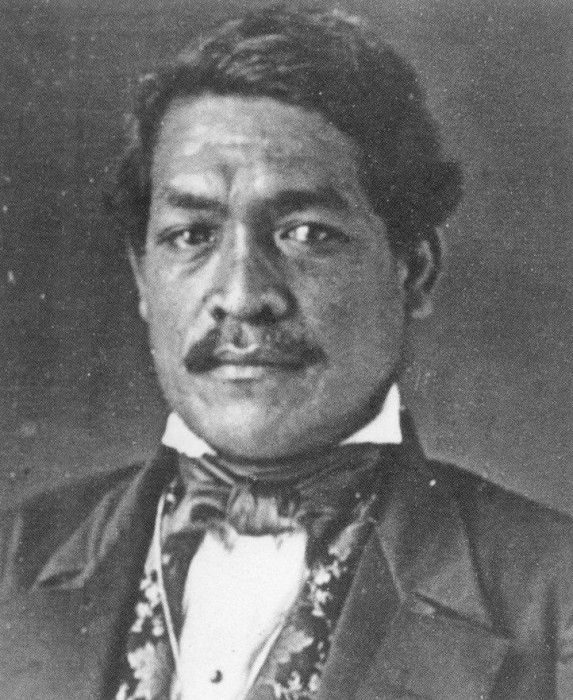

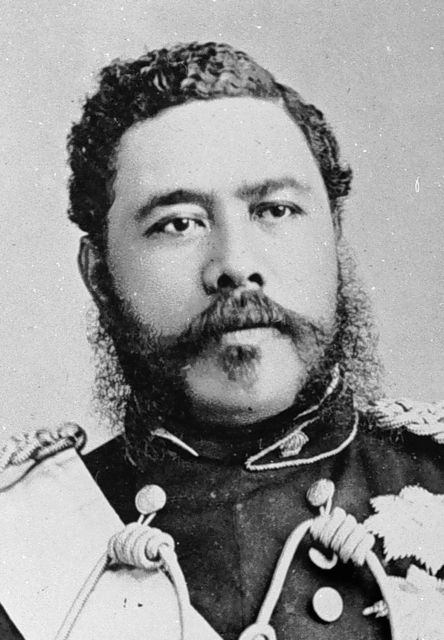

On July 8, 1842 King Kauikeaouli dispatched three delegates to America and Europe to ultimately secure recognition of Hawaiian independence by the major powers of the world. The Hawaiian Delegation, led by Timoteo Haʻalilio, was assured independence by the heads of state of the United States, Great Britain and France and on November 28, 1843 the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi was officially recognized as an independent country by Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland along with King Louis-Philippe of France through the signing of the Anglo-Franco proclamation at the Court of London, thereby making Hawaiʻi the first non-European nation in the world to be recognized as an independent country. Lā Kūʻokoʻa was celebrated throughout the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi from 1843 until 1893, when Queen Liliʻuokalani was illegally overthrown on January 17th with the assistance of the US Minister to Hawaiʻi, John L. Stevens.

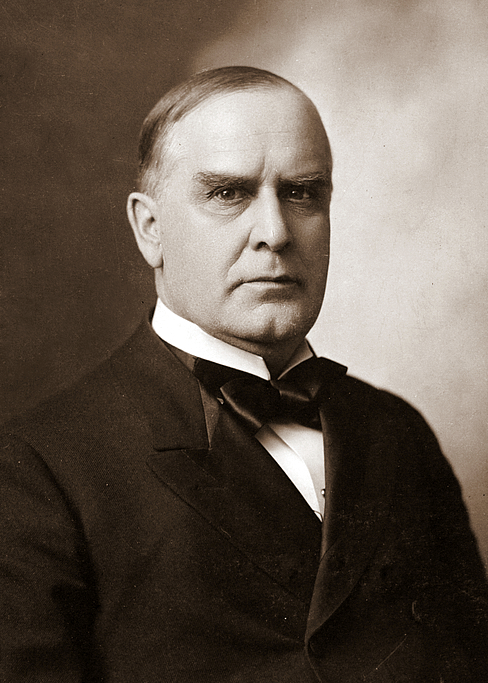

The United States of America’s only claim to acquiring Hawaiʻi is the Newland’s resolution, a joint resolution passed by Congress and signed by President McKinley on July 7, 1898. A joint resolution, though, is limited to United States territory, which Hawaiʻi obviously was not and is not a part of. Because a treaty was never ratified between the United States of America and the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi, Hawaiʻi has been and continues to be an independent country under an illegal and prolonged military occupation by the United States of America.

Building off of the momentum of the Department of Interior hearings held across the archipelago this summer, unity marches will also be held on the islands of Maui, Molokaʻi and Oʻahu to raise awareness in communities about Hawaiian history, our national heritage and of the ever-growing support for a free and independent Hawaiʻi.

###

For more information, please contact:

Kaho‘okahi Kanuha

Tel: 808-936-4249

Fax: 1-866-908-4619

naueikealohaaina@gmail.com

Twitter: @nauekealohaaina

#naueikealohaaina

#lakuokoa

#alohaainaoiaio

The Forgotten War of Aggression Against a Neutral State

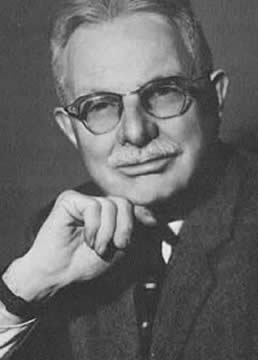

U.S. Representative Robert Hitt, Chairman of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, introduced the joint resolution of annexation of the Hawaiian Islands into the House of Representatives for debate on May 17, 1898. Hitt and other members of Congress attempt to justify the violation of international law, which ultimately passes the House of Representatives on June 15th and moves over to the Senate the following day.

U.S. Representative Robert Hitt, Chairman of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, introduced the joint resolution of annexation of the Hawaiian Islands into the House of Representatives for debate on May 17, 1898. Hitt and other members of Congress attempt to justify the violation of international law, which ultimately passes the House of Representatives on June 15th and moves over to the Senate the following day.

What these records reveal is that the act of war against the Hawaiian Kingdom, which stems from the United States admitted illegal overthrow of its government and deliberate failure to reinstate in 1893, was done with full knowledge and intent. The underlying purpose for the joint resolution was to take advantage of their puppet government that was installed by the United States Minister Stevens in 1893 calling itself in 1894 a so-called Republic, in order to seize the Hawaiian Islands during the Spanish-American War as a war measure. At the center of the plan was clearly the violation of Hawaiian neutrality under international law.

The Congressional record is foretelling of what the Hawaiian Islands have become today with 118 military sites that cover 20% of the territory of Hawai‘i and is headquarters for the United States Pacific Command together with its component commands of the U.S. Pacific Fleet headquartered at Pearl Harbor, U.S. Army Pacific headquartered at Fort Shafter, U.S. Marine Forces Pacific headquartered at Kane‘ohe Bay, and U.S. Pacific Air Forces headquartered at Hickam Air Base. All five of the headquarters are located on the Island of O‘ahu.

Here follows a snippet of Hitt’s testimony on the floor of the House of Representatives on June 11, 1898, and his reliance on military authorities that advocate seizing the Hawaiian Islands as a military necessity who testified before the House Committee on Foreign Affairs (vol. 31, Congressional Record, p. 5771-5772):

*******************************************************

Mr. HITT. I accept the opinion of men like Admiral Walker and Captain Mahan and General Schofield, Admiral Belknap, General Alexander, and Admiral Dupont and Chief Engineer Melville. It is a long list of great sailors and soldiers, distinguished strategists and authorities. The striking fact is that there is no dissent among them. These men, who are authorities, have all concurred as to the great importance of the islands. On one of the islands is Pearl Harbor, now unimproved, a possible stronghold and a refuge for a fleet, which, if fortified by the expenditure of half a million dollars and garrisoned and aided by the militia of the island and its resources, can be made impregnable to any naval force, however large.

I speak of a naval force. To capture it there must be a land force also. The possession of all the islands was stated by these able men, who were before the committee, to be essential, as they would furnish a valuable militia to promptly cooperate with a garrison of one or two regiments of artillery until, in the short distance from our shore, we could reinforce them with abundant military strength to repel the assault of the disembarking troops, who must come many thousands of miles farther than our own.

This is not my mere assertion or opinion on so grave a technical question. I am merely giving some of the leading points made by those whose names command the respect of the military and naval professions throughout the world and who have said that the possession not only of Pearl Harbor but of all that little group of islands is to us a necessity. I will give some expressions used by these distinguished authorities. I might give many more.

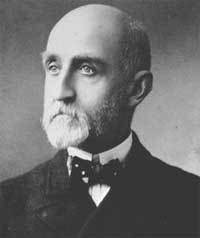

Captain Mahan, the most distinguished writer and authority of our time on the history of sea power, says:

Captain Mahan, the most distinguished writer and authority of our time on the history of sea power, says:

“It is obvious that if we do not hold the islands ourselves we cannot expect the neutrals in the war to prevent the other belligerent from occupying them; nor can the inhabitants themselves prevent such occupation. The commercial value is not great enough to provoke neutral interposition. In short, in war we should need a larger Navy to defend the Pacific coast, because we should have not only to defend our own coast, but to prevent, by naval force, an enemy from occupying the islands; whereas, if we preoccupied them, fortifications could preserve them to us. In my opinion it is not practicable for any trans-Pacific country to invade our Pacific coast without occupying Hawaii as a base.”

General Schofield, who spent three months on the islands and made a careful survey of Pearl River Harbor, stated to our committee:

General Schofield, who spent three months on the islands and made a careful survey of Pearl River Harbor, stated to our committee:

“Its secure anchorage for large fleets, its distance from the sea, beyond the reach of the guns of war ships, and the great ease with which the entrance to the harbor could be defended by batteries so as to make it a perfectly safe refuge for merchant shipping or naval cruisers, or even a fleet which might find it necessary under any circumstances to take refuge there; for coaling grounds, for navy-yard repair shops, storehouses, and everything of that kind.

The most important feature of all is that it economizes the naval force rather than increases it. It is capable of absolute defense by shore batteries; so that a naval fleet, after going there and replenishing its supplies and making what repairs are needed, can go away and leave the harbor perfectly safe under protection of the army. Then arises at once the question why this harbor will be of consequence to the United States. It has not been such subjects the study of a lifetime till now; but the conditions of the present war, it seems to me, ought to make it clear to everybody.

At this moment the Government is fitting out quite a large fleet of steamers at San Francisco to carry large detachments of troops and military supplies of all kinds to the Philippine Islands. Honolulu is almost in the direct route. That fleet, of course, will want very much to recoal at Honolulu, thus saving that amount of freight and tonnage for essential stores to be carried with it. Otherwise they would have to carry coal enough to carry them all the way from San Francisco to Manila and that would occupy a large amount of the carrying capacity of the fleet, and if they recoal at Honolulu all that will be saved. More than that, a fleet is liable at any time to meet with stress of weather, or perhaps a heavy storm, and there might be an accident to the machinery which will make it necessary to put into the nearest port possible for repairs and additional supplies. By the time it reaches there its coal supply may be well-nigh exhausted; it then has to replenish its coal supply to carry it to whatever port it could reach.

If I am not misinformed in regard to the laws of neutrality, the supply of coal that can be taken on board at neutral ports is only sufficient to bring it back to the nearest home port, and not enough to carry it across the ocean, so that if we had to regard Honolulu as a neutral port, we could only load up coal enough to bring us back to San Francisco. Now, let us suppose, on the other hand, that the Spanish navy in the Pacific as well as in the Atlantic, or both, were a little stronger than ours instead of being somewhat weaker. The first thing they would do would be to go and take possession of the Sandwich Islands and make them the base of naval operations against the Pacific coast.

You have only to consider to state of mind which exists all along the Atlantic coast under the erroneous apprehension that the Spanish fleet might possibly assail our coast to see what would be the case if the Spanish fleet were a good deal stronger than ours and took possession of Honolulu and made it a base of operations in attacking the points on the Pacific coast. We would be absolutely powerless, because we would have no fleet there to dispute the possession of the Sandwich Islands, whereas, if we held that place and fortified it so that a foreign navy could not take it, it could not operate against the Pacific coast at all, for it could not bring coal enough across the Pacific Ocean to sustain an attack on the Pacific coast. Then the Sandwich Islands would be a base for naval operations just as Puerto Rico is against the Atlantic coast. If Spain is strong enough to hold Puerto Rico, so that a squadron can replenish with supplies—coal, ammunition, and provisions—there, the whole Spanish fleet can raid our Atlantic coast at will.

It happens that in this war we have picked out the only nation in the world that is a little weaker than ourselves. The Spanish fleet on the Asiatic station was the only one of all the fleets we could have overcome as we did. Of course that can not again happen, for we will not be able to pick up so weak an enemy next time. We are liable at any time to get into a war with a nation which has a more powerful fleet than ours, and it is of vital importance, therefore, if we can, to hold the point from which they can conduct operations against our Pacific coast. Especially is that true until the Nicaragua Canal is finished, because we can not send a fleet from the Atlantic to the Pacific. We can no send them around Cape Horn and repel an attack there. If we had the canal finished, we would be much better off in that respect; but even then we would want the possession of a base very much.

We got a preemption title to those islands through the volunteer action of our American missionaries who went there and civilized and Christianized those people and established a Government that has no parallel in the history of the world, considering its age, and we made a preemption which nobody in the world thinks of disputing, provided we perfect out title. If we do not perfect it in due time, we have lost those islands. Any else can come in and undertake to get them.

So it seems to me the time is now ripe when this Government should do that which has been in contemplation from the beginning as a necessary consequence of the first action of our people in going there and settling those islands and establishing a good Government and education and the action of our Government from that time forward on every suitable occasion in claiming the right of American influence over those islands, absolutely excluding any other foreign power from any interference.”

The same eminent and experience soldier, when asked whether it would be sufficient to have Pearl Harbor without the islands, said we ought to have the islands to hold the harbor; that if left free and neutral complications would arise with foreign nations, who would take advantage of a weak little Republic with claims for damages enforced by war ships, as is frequently seen. If annexed, we would settle any dispute with a foreign nation; that we would be much stronger if we owned the islands as part of our territory, and would then also have the resources of the islands, which are so futile, for military supplies; that if we do not have the political control they may become Japanese; and we would be surrounded by a hostile people.

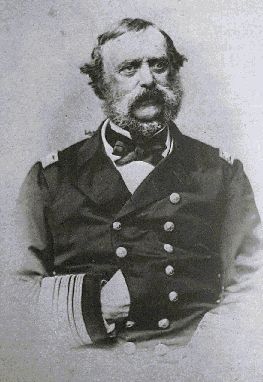

Admiral Walker, who has had long experience in the waters of the Hawaiian Islands, emphatically confirmed the views of General Schofield, especially that it would cost far less to protect the Pacific coast with the Hawaiian Islands than without them; that it would be taking a point of advantage instead of giving it to your enemy.

Admiral Dupont, in a report made as long ago as 1851, expressed his views in these words:

Admiral Dupont, in a report made as long ago as 1851, expressed his views in these words:

“It is impossible to estimate too highly the value and importance of the Sandwich Islands, whether in a commercial or military point of view. Should circumstances ever place them in our hands, they would prove the most important acquisition we could make in the whole Pacific Ocean—an acquisition intimately connected with our commercial and naval supremacy in those seas.”

An Act of War of Aggression: United States Invasion of the Hawaiian Kingdom on August 12, 1898

Incredible as it may sound, the United States committed an act of war of aggression against the Hawaiian Kingdom, being a neutral State, when it was at war with Spain in 1898, and that the United States has been in a war of aggression against Hawai‘i ever since. This war of aggression has lasted over 116 years, the longest ever since the Thirty Years War (1618-1648). According to Oppenheim’s International Law (7th ed.), p. 685, “hostilities against a neutral [State] on the part of either belligerent are acts of war, and not mere violations of neutrality. Thus the German attack on Belgium in 1914, to enable German troops to march through Belgian territory and attack France, created war between Germany and Belgium.”

The United States intent and purpose was to deliberately violate the neutrality of the Hawaiian Kingdom in order to fight Spain in its colonies of Guam and the Philippines, and after the war to use the Hawaiian Islands as a military outpost to protect the west coast of the United States as well as a base of operations for future wars. The action taken by the United States draws parallels to Germany’s occupation of neutral States during World War I and II, which at the time was thought of as unprecedented, but it wasn’t. The United States set the precedent in 1898.

On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded and occupied the neutral territories of Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg in order to fight France and Great Britain during World War II. The Nuremburg Tribunal concluded in its Nuremburg Judgment, that these invasions and subsequent occupations were unjustified acts of an aggressive war. The Tribunal stated:

“There is no evidence before the Tribunal to justify the contention that the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg were invaded by Germany because their occupation had been planned by England and France. British and French staffs had been operating in the Low Countries, but the purpose of this planning was to defend these countries in the event of a German attack.”

“The invasion of Belgium, Holland and Luxembourg was entirely without justification.”

“It was carried out in pursuance of policies long considered and prepared, and was plainly an act of aggressive war. The resolve to invade was made without any other consideration than the advancement of the aggressive policies of Germany.”

Of the three neutral States, the situation with Luxembourg bears the closest similarity to the Hawaiian Kingdom, whereby Germany also unilaterally annexed Luxembourg and initiated an aggressive campaign of “Germanization” and “Nazification” in the public schools. The United States also initiated an aggressive campaign of “Americanization” in the public schools that sought to obliterate the national character of the Hawaiian Kingdom and replace it with American patriotism.

Luxembourg was previously occupied by Germany for the same unjustified reasons from 1914-1918 during World War I.

The Hawaiian Kingdom also has Treaties of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation, with all three countries: Belgium (October 4, 1862), and the Netherlands and Luxembourg (October 16, 1862). William III, King of the Netherlands, who entered into the Dutch treaty, was also the Grand Duke of Luxembourg.

War, under international law, is considered an extension of a State’s sovereignty and therefore regulated by the laws of war as opposed to the laws of peace. International law separates the rights of belligerent States from the rights of neutral States. Laws of war—jus in bello, make up a part of customary international law until declared in law making treaties that began in the mid-nineteenth century. The first treaty was the 1856 Paris Declaration Respecting Maritime Law that abolished privateering, which later progressed to the 1899 and 1907 Hague Conventions, and the 1949 Geneva Conventions. In order for the laws of peace to return, war must come to an end. If not, then the laws of war—jus in bello, remain over the regions that are affected by the war itself. For the case of neutral States being illegally occupied during a war, being an act of war of aggression, its state of war with the belligerent occupant will continue until the occupying State ceases to occupy the neutral State, and the laws of war would still apply according to the 1907 Hague Convention, IV, and the 1949 Geneva Convention, IV.

Hawaiian neutrality began with King Kamehameha III’s proclamation of neutrality during the Crimean War on May 16, 1854. Since then, the Hawaiian government worked with other Powers, to include the United States, to have Hawai‘i’s neutrality respected in all subsequent wars. Neutrality provisions were inserted in the treaties with Sweden/Norway, Spain, Germany, and Italy.

Hawaiian neutrality began with King Kamehameha III’s proclamation of neutrality during the Crimean War on May 16, 1854. Since then, the Hawaiian government worked with other Powers, to include the United States, to have Hawai‘i’s neutrality respected in all subsequent wars. Neutrality provisions were inserted in the treaties with Sweden/Norway, Spain, Germany, and Italy.

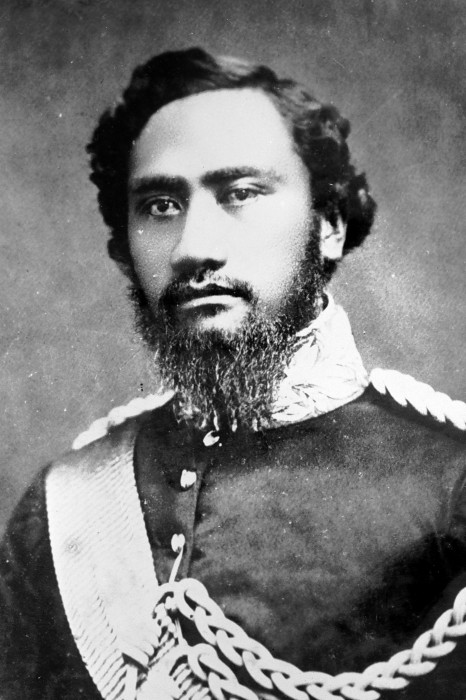

On April 7, 1855, His Majesty King Kamehameha IV opened the Legislative Assembly, and in his speech he reiterated the Kingdom’s neutrality.

“It is gratifying to me, on commencing my reign, to be able to inform you, that my relations with all the great Powers, between whom and myself exist treaties of amity, are of the most satisfactory nature. I have received from all of them, assurances that leave no room to doubt that my rights and sovereignty will be respected. My policy, as regards all foreign nations, being that of peace, impartiality and neutrality, in the spirit of the Proclamation by the late King, of the 16th May last, and of the Resolutions of the Privy Council of the 15th June and 17th July. I have given to the President of the United States, at his request, my solemn adhesion to the rule, and to the principles establishing the rights of neutrals during war, contained in the Convention between his Majesty the Emperor of all the Russias, and the United States, concluded in Washington on the 22nd July last.”

“It is gratifying to me, on commencing my reign, to be able to inform you, that my relations with all the great Powers, between whom and myself exist treaties of amity, are of the most satisfactory nature. I have received from all of them, assurances that leave no room to doubt that my rights and sovereignty will be respected. My policy, as regards all foreign nations, being that of peace, impartiality and neutrality, in the spirit of the Proclamation by the late King, of the 16th May last, and of the Resolutions of the Privy Council of the 15th June and 17th July. I have given to the President of the United States, at his request, my solemn adhesion to the rule, and to the principles establishing the rights of neutrals during war, contained in the Convention between his Majesty the Emperor of all the Russias, and the United States, concluded in Washington on the 22nd July last.”

The aforementioned Declarations and the 1854 Russian-American Convention represented the first recognition of the right of neutral States to conduct free trade without any hindrance from war. Stricter guidelines for neutrality were later established in the 1871 Treaty of Washington between the United States and Great Britain that was negotiated during the aftermath of the American Civil War, which also formed the basis of the Alabama claims arbitration in Geneva, Switzerland.

Without justification, the United States of America is directly responsible for the violation of the neutrality of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the occupation of its territory for military purposes during the 1898 Spanish-American War. Article XXVI of the Hawaiian-Spanish Treaty of October 29, 1863, provides, “All vessels bearing the flag of Spain, shall, in time of war, receive every possible protection, short of active hostility, within the ports and waters of the Hawaiian Islands, and Her Majesty the Queen of Spain engages to respect, in time of war the neutrality of the Hawaiian Islands, and to use her good offices with all the other powers having treaties with the same, to induce them to adopt the same policy toward the said Islands.”

According to the well-known American publicist on international law, Quincy Wright’s A Study of War, 2nd ed., p. 787, “The status of neutrality reached its climax in the nineteenth century with the especial support of Great Britain and the United States.” According to Wright, the rules of neutral status “were to a considerable extent codified in the American Neutrality act (1794), the British Foreign Enlistment Act (1819), the Declaration of Paris (1856), the rules of the Treaty of Washington (1871), the Hague Conventions (1907), and the Declaration of London (1909).”

According to the well-known American publicist on international law, Quincy Wright’s A Study of War, 2nd ed., p. 787, “The status of neutrality reached its climax in the nineteenth century with the especial support of Great Britain and the United States.” According to Wright, the rules of neutral status “were to a considerable extent codified in the American Neutrality act (1794), the British Foreign Enlistment Act (1819), the Declaration of Paris (1856), the rules of the Treaty of Washington (1871), the Hague Conventions (1907), and the Declaration of London (1909).”

Article VI of the 1871 Treaty of Paris between the United States and Great Britain declared that a neutral government is bound “Not to permit or suffer either belligerent to make use of its ports or waters as the base of naval operations against the other, or for the purpose of renewal or augmentation of military supplies or arms, or the recruitment of men.” The United States regarded this rule as declaratory of existing customary international law of the time. This rule was reproduced in Articles 1, 2 and 4 of the 1907 Hague Convention, V, which contained these provisions—“The territory of neutral Powers is inviolable” (Article 1); “Belligerents are forbidden to move troops or convoys, whether of munitions of war or of supplies, across the territory of a neutral Power” (Article 2); “Corps of combatants cannot be formed nor recruiting agencies opened on the territory of a neutral Power to assist the belligerents” (Article 4).

There is no doubt of the binding force of the 1863 Hawaiian-Spanish Treaty, the 1871 Treaty of Washington, and customary international law, as well as assurances by the United States through diplomatic notes since 1854, which guaranteed the neutrality of the Hawaiian Islands during the Spanish-American War.

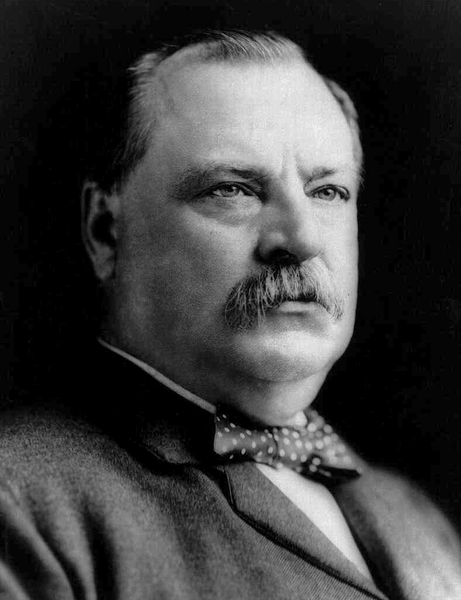

On December 18, 1893, an executive agreement was reached through exchange of diplomatic notes between United States President Grover Cleveland and the Hawaiian Kingdom’s Queen Lili‘uokalani, whereby the United States committed to the reinstatement of the constitutional government, and thereafter the Queen to grant a full pardon to a minority of insurgents who participated with the United States Legation in the unlawful overthrow of the Hawaiian government. Prior to the agreement, the United States initiated a presidential investigation on April 1, 1893 after ordering U.S. troops to return to the U.S.S. Boston that was anchored in Honolulu harbor. The investigation was concluded on October 18, 1893 and concluded that the United States was entirely responsible for the unlawful overthrow of the Hawaiian government by its military force.

On December 18, 1893, an executive agreement was reached through exchange of diplomatic notes between United States President Grover Cleveland and the Hawaiian Kingdom’s Queen Lili‘uokalani, whereby the United States committed to the reinstatement of the constitutional government, and thereafter the Queen to grant a full pardon to a minority of insurgents who participated with the United States Legation in the unlawful overthrow of the Hawaiian government. Prior to the agreement, the United States initiated a presidential investigation on April 1, 1893 after ordering U.S. troops to return to the U.S.S. Boston that was anchored in Honolulu harbor. The investigation was concluded on October 18, 1893 and concluded that the United States was entirely responsible for the unlawful overthrow of the Hawaiian government by its military force.

President Cleveland declared in his message to Congress on December 18, 1893, “And so it happened that on the 16th day of January, 1893, between four and five o’clock in the afternoon, a detachment of marines from the United States steamer Boston, with two pieces of artillery, landed at Honolulu. The men, upwards of 160 in all, were supplied with double cartridge belts filled with ammunition and with haversacks and canteens, and were accompanied by a hospital corps with stretchers and medical supplies. This military demonstration upon the soil of Honolulu was of itself an act of war, unless made either with the consent of the Government of Hawaii or for the bona fide purpose of protecting the imperiled lives and property of citizens of the United States. But there is no pretense of any such consent on the part of the Government of the Queen, which at that time was undisputed and was both the de facto and the de jure government.” Cleveland also concluded that the provisional government that seized control of the constitutional government with U.S. troops, “was neither a government de facto nor de jure,” but self-declared.

President Cleveland declared in his message to Congress on December 18, 1893, “And so it happened that on the 16th day of January, 1893, between four and five o’clock in the afternoon, a detachment of marines from the United States steamer Boston, with two pieces of artillery, landed at Honolulu. The men, upwards of 160 in all, were supplied with double cartridge belts filled with ammunition and with haversacks and canteens, and were accompanied by a hospital corps with stretchers and medical supplies. This military demonstration upon the soil of Honolulu was of itself an act of war, unless made either with the consent of the Government of Hawaii or for the bona fide purpose of protecting the imperiled lives and property of citizens of the United States. But there is no pretense of any such consent on the part of the Government of the Queen, which at that time was undisputed and was both the de facto and the de jure government.” Cleveland also concluded that the provisional government that seized control of the constitutional government with U.S. troops, “was neither a government de facto nor de jure,” but self-declared.

After President Cleveland submitted a request to Congress for authorization to use force in order to reinstate the constitutional government of the Queen, which had been usurped by the United States, the House of Representatives and the Senate each passed resolutions calling upon the President to not carry out the executive agreements and also issued warnings to foreign States to not intervene in the Hawaiian situation.

U.S. Senate resolution, May 31, 1894, 53 Cong., 2nd Sess., 5499 (1894):

“Resolved, That of right it belongs wholly to the people of the Hawaiian Islands to establish and maintain their own form of government and domestic polity; that the United States ought in nowise to interfere therewith, and that any intervention in the political affairs of these islands by any other government will be regarded as an act unfriendly to the United States.”

U.S. House resolution, February 7, 1894, 53 Cong., 2nd Sess., 2000 (1894):

“Resolved, First. That it is the sense of this House that the action of the United States minister in employing United States naval forces and illegally aiding in overthrowing the constitutional Government of the Hawaiian Islands in January, 1893, and in setting up in its place a Provisional Government not republican in form and in opposition to the will of a majority of the people, was contrary to the traditions of our Republic and the spirit of our Constitution, and should be condemned. Second. That we heartily approve the principle announced by the President of the United States that interference with the domestic affairs of an independent nation is contrary to the spirit of American institutions. And it is further the sense of this House that the annexation of the Hawaiian Islands to our country, or the assumption of a protectorate over them by our Government is uncalled for and inexpedient; that the people of that country should have their own line of policy, and that foreign intervention in the political affairs of the islands will not be regarded with indifference by the Government of the United States.”

Without Congressional support, the President could not deploy U.S. troops back to Hawai‘i in order to reinstate the constitutional government and the insurgents hired mercenaries from the United States to fill the vacuum left by the departure of U.S. troops. On July 4, 1894, the insurgency was renamed the Republic of Hawai‘i, which Congress over one hundred years later in its apology for the 1893 overthrow the Hawaiian Kingdom government, U.S. Public Law 103-150, admitted was “self-declared.”

The insurgents were desperately holding on to power until a new President entered office so that the original plan of annexation could be completed. On March 4, 1897, President William McKinley entered office and another attempt to annex by treaty failed as a result of protests by Queen Lili‘uokalani and by the people.

The insurgents were desperately holding on to power until a new President entered office so that the original plan of annexation could be completed. On March 4, 1897, President William McKinley entered office and another attempt to annex by treaty failed as a result of protests by Queen Lili‘uokalani and by the people.

On April 25, 1898, Congress declared war on Spain. Battles were fought in the Spanish colonies of Puerto Rico and Cuba, as well as the Spanish colonies of the Philippines and Guam. After Commodore Dewey defeated the Spanish Fleet in the Philippines on May 1, 1898, U.S. Representative Francis Newlands, submitted House joint resolution no. 259 for the annexation of the Hawaiian Islands to the House Committee on Foreign Affairs on May 4, 1898. Six days later, hearings were held on the Newlands resolution, and in testimony submitted to the committee, U.S. military leaders called for the immediate violation of Hawaiian neutrality and occupation of the Hawaiian Islands due to military necessity for both during the war with Spain and for any future wars that the United States would enter.

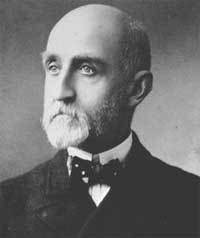

U.S. Naval Captain Alfred Mahan stated to the committee: “It is obvious that if we do not hold the islands ourselves we cannot expect the neutrals in the war to prevent the other  belligerent from occupying them; nor can the inhabitants themselves prevent such occupation. The commercial value is not great enough to provoke neutral interposition. In short, in war we should need a larger Navy to defend the Pacific coast, because we should have not only to defend our own coast, but to prevent, by naval force, an enemy from occupying the islands; whereas, if we preoccupied them, fortifications could preserve them to us. In my opinion it is not practicable for any trans-Pacific country to invade our Pacific coast without occupying Hawaii as a base.”

belligerent from occupying them; nor can the inhabitants themselves prevent such occupation. The commercial value is not great enough to provoke neutral interposition. In short, in war we should need a larger Navy to defend the Pacific coast, because we should have not only to defend our own coast, but to prevent, by naval force, an enemy from occupying the islands; whereas, if we preoccupied them, fortifications could preserve them to us. In my opinion it is not practicable for any trans-Pacific country to invade our Pacific coast without occupying Hawaii as a base.”

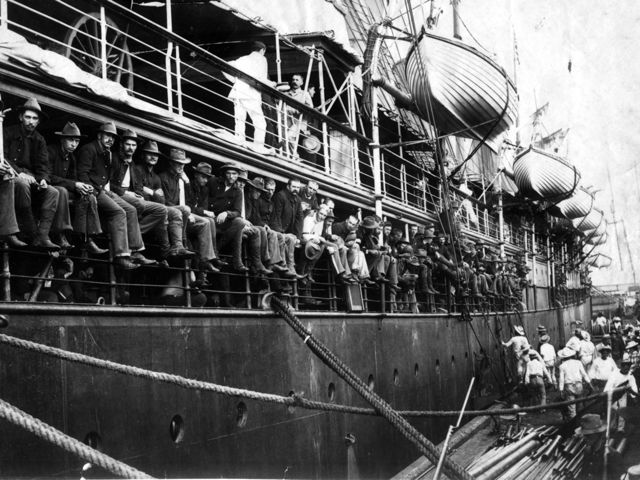

While the debates ensued in both the U.S. House and Senate, the U.S.S. Charleston, a protected cruiser, was ordered to lead a convoy of 2,500 troops to reinforce U.S. troops in the Philippines and Guam. These troops were boarded on the transport ships of the City of Peking, the City of Sidney and the Australia. In a deliberate violation of Hawaiian neutrality during the war as well as of international law, the convoy, on May 21, set a course to the Hawaiian Islands for re-coaling purposes. The convoy arrived in Honolulu on June 1, and took on 1,943 tons of coal before it left the islands on June 4.

As soon as it became apparent that the self-declared Republic of Hawai‘i, a puppet regime of the United States since 1893, had welcomed the U.S. naval convoys and assisted in re-coaling their ships, H. Renjes, Spanish Vice-Consul in Honolulu, lodged a formal protest on June 1, 1898. Minister Harold Sewall, from the U.S. Legation in Honolulu, notified Secretary of State William R. Day of the Spanish protest in a dispatch dated June 8. Renjes declared, “In my capacity as Vice Consul for Spain, I have the honor today to enter a formal protest with the Hawaiian Government against the constant violations of Neutrality in this harbor, while actual war exists between Spain and the United States of America.” A second convoy of troops bound for the Philippines, on the transport ships the China, Zelandia, Colon, and the Senator, arrived in Honolulu on June 23, and took on 1,667 tons of coal.

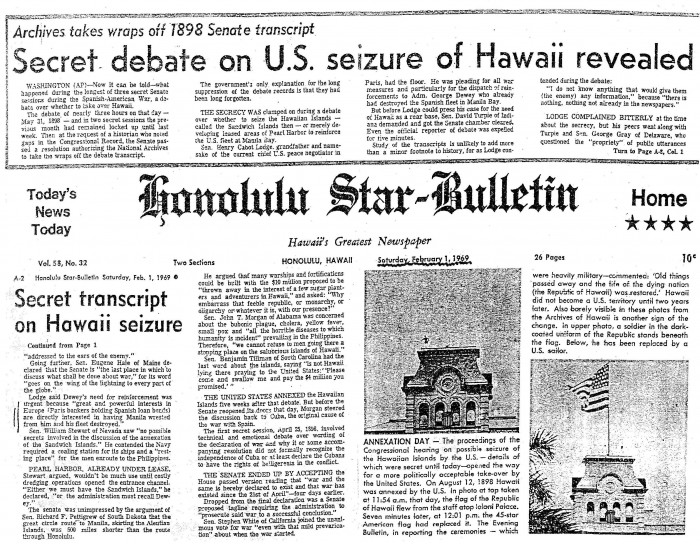

In a secret session of the U.S. Senate on May 31, 1898, Senator William Chandler warned of the consequences Alabama claims arbitration in Geneva, whereby Great Britain was found guilty of violating its neutrality during the American Civil War and compensated the United States with 15.5 million dollars in gold. Chandler cautioned, p. 278 of the secret session transcripts, “What I said was that if we destroyed the neutrality of Hawai‘i Spain would have a claim against Hawai‘i which she could enforce according to the principles of the Geneva Award and make Hawai‘i, if she were able to do it, pay for every dollar’s worth of damage done to the ships of property of Spain by the fleet that may go out of Hawai‘i.”

In a secret session of the U.S. Senate on May 31, 1898, Senator William Chandler warned of the consequences Alabama claims arbitration in Geneva, whereby Great Britain was found guilty of violating its neutrality during the American Civil War and compensated the United States with 15.5 million dollars in gold. Chandler cautioned, p. 278 of the secret session transcripts, “What I said was that if we destroyed the neutrality of Hawai‘i Spain would have a claim against Hawai‘i which she could enforce according to the principles of the Geneva Award and make Hawai‘i, if she were able to do it, pay for every dollar’s worth of damage done to the ships of property of Spain by the fleet that may go out of Hawai‘i.”

He later poignantly asked Senator Stephen White (p. 279), “whether he is willing to have the Navy and Army of the U.S. violate the neutrality of Hawai‘i?” White responded, “I am not, as everybody knows, a soldier, nor am I familiar with military affairs, but if I were conducting this Govt. and fighting Spain I would proceed so far as Spain was concerned just as I saw fit.”

Senator Henry Cabot Lodge answered Senator White’s question directly (p. 280). “I should have argued then what has been argued ably since we came into secret legislative session, that at this moment the Administration was compelled to violate the neutrality of those islands, that protests from foreign representatives had already been received and complications with other powers were threatened, that the annexation or some action in regard to those islands had become a military necessity.”

Senator Henry Cabot Lodge answered Senator White’s question directly (p. 280). “I should have argued then what has been argued ably since we came into secret legislative session, that at this moment the Administration was compelled to violate the neutrality of those islands, that protests from foreign representatives had already been received and complications with other powers were threatened, that the annexation or some action in regard to those islands had become a military necessity.”

The transcripts of the Senate’s secret session were not made public until 1969.

Commenting on the United States flagrant violation of Hawaiian neutrality, T.A. Bailey wrote in his article The United States and Hawaii During the Spanish-American War, “The position of the United States was all the more reprehensible in that she was compelling a weak nation to violate the international law that had to a large degree been formulated by her own stand on the Alabama claims. Furthermore, in line with the precedent established by the Geneva award, Hawai‘i would be liable for every cent of damage caused by her dereliction as a neutral, and for the United States to force her into this position was cowardly and ungrateful. At the end of the war, Spain or cooperating power would doubtless occupy Hawai‘i, indefinitely if not permanently, to insure payment of damages, with the consequent jeopardizing of the defenses of the Pacific Coast.”

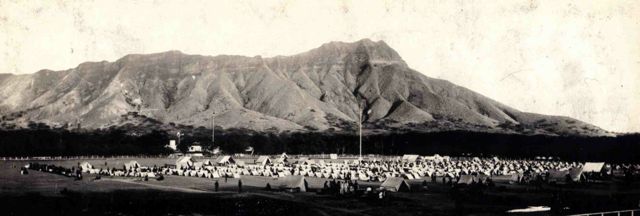

On July 6, the joint resolution passed both House and Senate, despite objections by Congressmen that annexation could only take place by a treaty and not by a domestic statute, and President McKinley signed the measure on July 7, 1898. On August 12, 1898, at 12 noon, the Hawaiian Kingdom was invaded by the United States with full military display on the grounds of the ‘Iolani Palace. The first military base was Camp McKinley established on August 16, 1898 at Kapi‘olani Park adjacent to the famous Waikiki beach and Diamond Head mountain.

Since the invasion, the Hawaiian Kingdom has served as a base of operations for United States troops during World War I and World War II. In 1947, the United States Pacific Command (USPACOM), being a unified combatant command, was established as an outgrowth of the World War II command structure, with its headquarters on the Island of O‘ahu. USPACOM has served as a base of operations during the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Gulf War, the Afghan War, the Iraq War, and the current war against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). There are currently 118 U.S. military sites throughout the Hawaiian Kingdom that comprise 230,929 acres (20%) of Hawaiian territory.

The United States Navy’s Pacific Fleet headquartered at Pearl Harbor on the Island of O‘ahu also hosts the Rim of the Pacific Exercise (RIMPAC) every other even numbered year, which is the largest international maritime warfare exercise. RIMPAC is a multinational, sea control and power projection exercise that collectively consists of activity by the U.S. Army, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Naval forces, as well as military forces from other foreign States. During the month long exercise, RIMPAC training events and live fire exercises occur in open-ocean and at the military training locations throughout the Hawaiian Islands. In 2014, Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Colombia, France, India, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, People’s Republic of China, Peru, Republic of Korea, Republic of the Philippines, Singapore, Tonga, and the United Kingdom participated in the RIMPAC exercises.

Since the belligerent occupation by the United States began on August 12, 1898 during the Spanish-American War, the Hawaiian Kingdom, as a neutral state, has been in a war of aggression for over a century. Although it is not a state of war in the technical sense that was produced by a declaration of war, it is, however, a war in the material sense that Yoram Dinstein’s War, Aggression and Self-Defense, 2nd ed., p. 16, says, is “generated by actual use of armed force, which must be comprehensive on the part of at least one party to the conflict.” The military action by the United States on August 12, 1898 against the Hawaiian Kingdom triggered the change from a state of peace into a state of war of aggression—jus in bello, where the laws of war would apply.

When neutral territory is occupied, however, the laws of war are not applied in its entirety. According to Sakuye Takahashi’s International Law applied to the Russo-Japanese War, p. 251, Japan limited its application of the Hague Convention to its occupation of Manchuria, being a province of a neutral China, in its war against Russia, to Article 42—on the elements and sphere of military occupation, Article 43—on the duty of the occupant to respect the laws in force in the country, Article 46—concerning family honour and rights, the lives of individuals and their private property as well as their religious conviction and the right of public worship, Article 47—on prohibiting pillage, Article 49—on collecting the taxes, Article 50—on collective penalty, pecuniary or otherwise, Article 51—on collecting contributions, Article 53—concerning properties belonging to the state or private individuals, which may be useful in military operations, Article 54—on material coming from neutral states, and Article 56—on the protection of establishments consecrated to religious, warship, charity, etc.

Hawai‘i’s invasion and occupation was anomalous and without precedent. The closest similarity to the Hawaiian situation would not take place until sixteen years later when Germany occupied the neutral States of Belgium and Luxembourg in its war against France from 1914-1918, and its second war against France where both States were occupied again from 1940-1945. The Allies considered Germany’s actions to be acts of aggression. According to James Wilford Garner’s International Law and the World War, vol. II, p. 251, the “immunity of a neutral State from occupation by a belligerent is not dependent upon special treaties, but is guaranteed by the Hague convention as well as the customary law of nations.”

Now that this information is coming to light after a century of indoctrination through “Americanization,” the entire world is being transformed by the harsh reality that Hawai‘i has been in a region of war since 1898. Stemming from this reality is the ongoing commission of war crimes, as well as defects in real property ownership that affect investments, such as mortgage-backed securities. The subprime mortgage crisis took place as a result of mortgages in these securities going into foreclosures, but a new crisis on the horizon is that these mortgages that originated in the Hawaiian Islands were never valid in the first place. Hawaiian Kingdom law was not complied with in the transfer of real property and the securing of mortgages since January 17, 1893.

In light of this severity, the acting Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom has developed a comprehensive plan through the decree of provisional laws to address this problem head on that is based on international law and precedents. The acting government is in the process of implementation according to the laws of war.

Weblog Etiquette

The acting government would like to extend a sincere gratitude and appreciation to all those who have visited this weblog and those that have provided commentary to the blog entries. Our intention is to inform the general public both domestic and abroad of the prolonged and illegal occupation of our country, the Hawaiian Kingdom. This blog is not run as a typical weblog with a webmaster that moderates the commentary. Comments are encouraged, but when commentaries are disrespectful and uses profanity, this weblog reserves the right to prevent the commentary from being posted. This blog has received many comments that were distasteful, disrespectful, and tattered with profanity.

As we are dealing with over a century of Americanization here in the islands, this blog has to maintain a standard of integrity when disseminating information regarding our country, the Hawaiian Kingdom, international laws, and the laws of occupation.

The weblog has also come under a very high volume of brute force cyber attacks that have attempted to penetrate the website and therefore this weblog has to maintain a high standard of security. Previously, the weblog installed a plugin where individuals logging into this blog could readily view the visitors, domain names and their geographic locations on google map, but after a short test run it was decided to remove the plugin because it opened the weblog to an outside link that we could not confirm to be safe. In other words, it could have opened a back door to cyber attacks.

Again the acting government extends its appreciation and is humbled by such a high volume of visitors from Hawai‘i and the international community and we will continue to provide information that we feel can serve to counter over a century of denationalization and to reinstate a Hawaiian national consciousness that was nearly obliterated through an institutional program of Americanization.

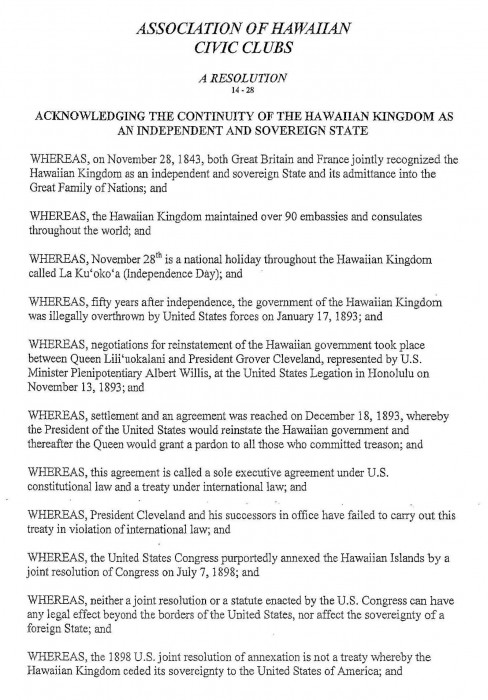

Association of Hawaiian Civic Clubs Acknowledges the Continued Existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom

The first Hawaiian Civic Club was established in 1918 by Prince Kuhio Kalaniana‘ole. The Association of Hawaiian Civic Clubs (AHCC) is a confederacy of 67 clubs that advocates “for improved welfare of native Hawaiians in culture, health, economic development, education, social welfare, and nationhood,” that was established in 1959. According to Dot Uchima, Recording Secretary, the AHCC “has established a reputation of serious consideration on community issues and mana‘o of the membership as it convenes annually at locations where clubs are represented,” and that “many resolutions adopted by the Association’s delegation at convention have served as the basis for proposed state and federal legislation.”

The first Hawaiian Civic Club was established in 1918 by Prince Kuhio Kalaniana‘ole. The Association of Hawaiian Civic Clubs (AHCC) is a confederacy of 67 clubs that advocates “for improved welfare of native Hawaiians in culture, health, economic development, education, social welfare, and nationhood,” that was established in 1959. According to Dot Uchima, Recording Secretary, the AHCC “has established a reputation of serious consideration on community issues and mana‘o of the membership as it convenes annually at locations where clubs are represented,” and that “many resolutions adopted by the Association’s delegation at convention have served as the basis for proposed state and federal legislation.”

The AHCC is a very influential civic body that is comprised of many leaders in the community, business community and government. All resolutions adopted by the Association are also given to the Governor of Hawai‘i, State Senate President, State Speaker of the House, State Senate Committee on Hawaiian Affairs, State House Committee on Hawaiian Affairs, Office of Hawaiian Affairs Chair of the Board of Trustees, and all County Mayors. The President of the AHCC is Soulee L. K. O. Stroud.

The AHCC is a very influential civic body that is comprised of many leaders in the community, business community and government. All resolutions adopted by the Association are also given to the Governor of Hawai‘i, State Senate President, State Speaker of the House, State Senate Committee on Hawaiian Affairs, State House Committee on Hawaiian Affairs, Office of Hawaiian Affairs Chair of the Board of Trustees, and all County Mayors. The President of the AHCC is Soulee L. K. O. Stroud.

From October 26 through November 2, 2014, Hawaiian Civic Clubs from across the Hawaiian Islands and the United States met at its annual convention held at the Waikoloa Beach Resort Marriot hotel on the Island of Hawai‘i. Ka Lei Maile Ali‘i Hawaiian Civic Club introduced resolution 14-28, acknowledging the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom. After a lively debate by the delegates of the many clubs in its plenary session, the resolution was passed on November 1, 2014.

ACKNOWLEDGING THE CONTINUITY OF THE HAWAIIAN KINGDOM AS AN INDEPENDENT AND SOVEREIGN STATE

WHEREAS, on November 28, 1843, both Great Britain and France jointly recognized the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent and sovereign State and admittance into the Great Family of Nations; and

WHEREAS, the Hawaiian Kingdom maintained over 90 embassies and consulates throughout the world; and

WHEREAS, November 28th is a national holiday throughout the country called La Ku‘oko‘a (independence day); and

WHEREAS, fifty years after independence, the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom was illegally overthrown by United States forces on January 17, 1893; and

WHEREAS, negotiations for reinstatement of the Hawaiian government took place between Queen Lili‘uokalani and President Grover Cleveland, represented by U.S. Minister Plenipotentiary Albert Willis, at the United States Legation in Honolulu on November 13, 1893; and

WHEREAS, settlement and an agreement was reached on December 18, 1893, whereby the President would reinstate the Hawaiian government and thereafter the Queen would grant a pardon to all those who committed treason; and

WHEREAS, this agreement is called a sole executive agreement under U.S. constitutional law and a treaty under international law; and

WHEREAS, President Cleveland and his successor in office have not carried out this treaty in violation of international law; and

WHEREAS, the United States Congress purportedly annexed the Hawaiian Islands by a joint resolution of Congress on July 7, 1898; and

WHEREAS, neither a joint resolution or a statute enacted by the Congress can have any legal effect beyond the borders of the United States and affect the sovereignty of a foreign State; and

WHEREAS, the 1898 joint resolution of annexation is not a treaty whereby the Hawaiian Kingdom ceded its sovereignty to the United States of America; and

WHEREAS, on August 12, 1898 at 12 noon, during the Spanish-American War, the United States began the illegal and prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom; and

WHEREAS, in 2001, the Permanent Court of Arbitration, in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, acknowledged in its arbitral award that “in the nineteenth century the Hawaiian Kingdom existed as an independent State recognized as such by the United States of America, the United Kingdom and various other States, including by exchanges of diplomatic or consular representatives and the conclusion of treaties”; and

WHEREAS, under international law all States have sovereign equality, and have equal rights and duties as co-equal members of the international community regardless of their economic, social and political differences; and

WHEREAS, according to international law there is a legal presumption that occupation does not affect the continuity of the State even when there is no government claiming to represent the occupied State.

NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED, by the Association of Hawaiian Civic Clubs at its 55th annual convention at Waikoloa, Hawai‘i, this 1st day of November, 2014, that it acknowledges the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent and sovereign State.

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED that a certified copy of this resolution be given to the Governor of Hawaii, State Senate President, State Speaker of the House, State Senate Committee on Hawaiian Affairs, State House Committee on Hawaiian Affairs, Office of Hawaiian Affairs Chair of the Board of Trustees, and all County Mayors.

On November 1, 2014 at the AHCC Convention Annelle Amaral was elected to succeed Stroud as President.

On November 1, 2014 at the AHCC Convention Annelle Amaral was elected to succeed Stroud as President.

Circle Hawai‘i Island Convoy – La Ku‘oko‘a (Independence Day)

U.S. Congressman Clark Says Annexation Against the Will of the Hawaiian People

After the defeat of the Spanish Pacific Squadron in the Philippines on May 1, 1898, just one month into the Spanish-American War, Congressman Francis Newlands (D-Nevada), submitted House resolution no. 259 for the annexation of the Hawaiian Islands to the

After the defeat of the Spanish Pacific Squadron in the Philippines on May 1, 1898, just one month into the Spanish-American War, Congressman Francis Newlands (D-Nevada), submitted House resolution no. 259 for the annexation of the Hawaiian Islands to the House Committee on Foreign Affairs on May 4, 1898. Six days later, hearings were held on the Newlands resolution, and on May 17, 1898, Chairman Robert Hitt (R-Illinois) reported the Newlands resolution out of the Committee of Foreign Affairs, and debates ensued in the House of Representatives until the resolution was passed on June 15, 1898.

House Committee on Foreign Affairs on May 4, 1898. Six days later, hearings were held on the Newlands resolution, and on May 17, 1898, Chairman Robert Hitt (R-Illinois) reported the Newlands resolution out of the Committee of Foreign Affairs, and debates ensued in the House of Representatives until the resolution was passed on June 15, 1898.

On June 11, 1898, Congressman Hitt began the debate by giving a lengthy testimony calling for the annexation of the Hawaiian Islands as a military necessity. One of the opponents to the scheme of annexation was Congressman Charles Nelson Clark (R-Missouri). He too gave a lengthy testimony on the floor of the House during the debate and one of his key points centered on the lack of support the so-called Republic of Hawai‘i had from the people of the Hawaiian Islands. He was making specific reference to the signature petition against the treaty of annexation by the Hawaiian Patriotic League that was submitted by Senator George Hoar (R-Massachusetts) after meeting with the officers of the league in Washington, D.C. This signature petition was a major reason why the Senate failed to acquire the necessary two-thirds vote to ratify a treaty of annexation that was signed by the McKinley administration and the so-called Republic of Hawai‘i. The treaty failed.

On June 11, 1898, Congressman Hitt began the debate by giving a lengthy testimony calling for the annexation of the Hawaiian Islands as a military necessity. One of the opponents to the scheme of annexation was Congressman Charles Nelson Clark (R-Missouri). He too gave a lengthy testimony on the floor of the House during the debate and one of his key points centered on the lack of support the so-called Republic of Hawai‘i had from the people of the Hawaiian Islands. He was making specific reference to the signature petition against the treaty of annexation by the Hawaiian Patriotic League that was submitted by Senator George Hoar (R-Massachusetts) after meeting with the officers of the league in Washington, D.C. This signature petition was a major reason why the Senate failed to acquire the necessary two-thirds vote to ratify a treaty of annexation that was signed by the McKinley administration and the so-called Republic of Hawai‘i. The treaty failed.

Here follows Congressman Clark’s testimony during the debate on June 11, 1898 (vol. 31, Congressional Record, p. 5793):

*******************************************************

AGAINST THE WILL OF THE HAWAIIAN PEOPLE

The cornerstone of this Republic is the proposition enunciated by Thomas Jefferson, the chief priest, apostle, and prophet of constitutional liberty—“Governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

If that proposition is not true, then the American Revolution was a monstrous crime; Washington, Warren, Montgomery, Greene, Marion, and all that band of heroes were turbulent traitors to King George III; John Hancock, Old John Adams, Patrick Henry, Richard Henry Lee, and their Congressional compeers pestilent disturbers of the peace; and all the blood shed in our two wars with Great Britain was wanton and wicked waste. If that proposition is not true, William McKinley is this day exercising functions usurped from Victoria Guelph, and this body is composed of mouthy brawlers doing unlawfully those things which the English House of Commons has the sole right to do.

If that proposition is not true, you, Mr. Speaker, are not Speaker de jure, but only Speaker de facto, interfering pro tanto with the prerogatives of the speaker of the English House of Commons, Mr. Gully, who is the grandson of a professional pugilist. [Laughter and applause.]

This annexation scheme is in flagrant violation of that basic principle of our Republic, for many thousand Hawaiians—more than the entire male adult population—have solemnly protested against the sale and delivery of their country to us by a little gang of adventurers who, claiming to be the whole thing, are offering to us a property of which they have robbed the rightful owners. And now America, which has been solemnly declared by the Supreme Court to be a Christian land, is to be made the receiver of these stolen Hawaiian goods.

If an ordinary citizen receives stolen goods, he commits a penitentiary offense. Wherein, I beg leave to inquire, is the difference of principle between in stealing ordinary property and in stealing an island or a group of islands, or in receiving them after they are stolen? The only justification lies in the thievish theory that if the theft is big enough, it ceases to be a crime and takes on the character and complexion of a virtue, and the perpetrators thereof, instead of being consigned to the striped uniforms, cramped quarters, meager diet, and hard labor of felons, are to be hailed as statesmen and rewarded with the plaudits of a grateful people—a theory which, I regret to say, is growing in this country.

But the jingoes tell us that this protest of the Hawaiians is all bogus, gotten up by designing knaves, and that the Hawaiians are falling over each other in their eagerness for annexation. If this is true, why not submit this annexation scheme to a popular vote in Hawaii, as was done in the case of Texas, and which was provided for in the treaty once negotiated with Santo Domingo, but which happily was never ratified, or have a plebiscite, as Napoleon III was in the habit of doing whenever he felt like it or wished to cure himself of ennui produced by wearing his uncle’s heavy crown, which was too large for him? That would be fair and would remove one difficulty. Certainly Mr. Sanford B. Dole could guarantee that every vote in favor of annexation would be counted at least once.

Does he or do his sponsors here shrink from the test of Hawaiian manhood suffrage on that proposition?

If a fair election on that proposition can not be had, what assurance have we that fair elections can be had hereafter, if we annex these islands? If the Hawaiians are not fit to vote on a proposition of vital interest to themselves, who will have the effrontery to say that they are fit to vote for all coming time on propositions of vital interest to us and to our posterity?

If governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed, how does it happen that the Hawaiians are to have no voice in a performance which transforms their country from an independent nation into a mere outpost of this Republic?

Let him answer who can.

This submission to a vote of the Hawaiian male adults of a proposition decisive of their destiny ought to be insisted on by Congress as a condition precedent to even considering annexation.

This is the American method of procedure—a method bottomed on the eternal principles of wisdom, justice, and liberty.

We should demand a free ballot and a fair count for the Hawaiians, whose patrimony has been appropriated by President Dole and his partners in the oligarchy.

The annexation shouters claim that the Hawaiian names appended to the remonstrance are largely fictitious, and chiefly secured as signers under false pretenses. We deny it. Issue is squarely joined on an important matter of fact. It can be settled by a vote of the Hawaiian males over 21 years of age. Who can deny that that is a fair test?

All the machinery of elections is in the hands of the little coterie of oligarchists. They are able, resolute, ambitious men. They can be relied upon to see to it that every annexation voter votes and that his vote is counted. They can also be relied on to see to it that not an unlawful vote is cast against the scheme of annexation, for their fortunes depend upon annexation. Can anything be more clearly just? Is President Dole afraid of the verdict of his own people? I pause for a reply.

None of his friends answer, so I will answer myself. He can not be induced to submit this scheme to a popular manhood suffrage vote, for the very good reason that he knows that he and his friends hold office through usurpation and that the vast majority of the Hawaiian people are bitterly opposed to him and all his works. He the friend of liberty, is he? How does it happen, then, that while under the monarchy 14,000 persons were permitted to vote, only 2,800 are given the elective franchise under the oligarchy?

Let it be remembered also that a large percentage of these 2,800 voters have been colonized in Hawaii by Dole & Co. since they have been conducting the Government. What a misleading misnomer is it to dignify this little handful of close-corporation oligarchists with the name of a republic! What a burlesque upon truth, what a travesty upon justice, what an affront to intelligence to assert that Dole and his gang have any claims upon us or upon any other friends of representative government and human freedom!

Oh, yes, but we are told that all male citizens of the Sandwich Islands can vote who will swear that they will support the present Republic and the present constitution of Hawaii. Now, at first blush that seems perfectly fair; but it is a delusion and a snare, as will readily appear from this fact: The constitution, which the Hawaiian people never had any hand in adopting, provides for this very scheme of annexation, which the Hawaiian people detest. That condition for voting is a very skillful contrivance. It exhausted human ingenuity to invent it as is worthy of Machiavelli himself. In order to vote at all a citizen of the Sandwich Islands must solemnly swear to support a constitution which deprives his country of its nationality. What man who has any reputation to lose indorses such a swindle on a feeble people? Under it only about 2,800 persons to vote, and that is about the number in favor of annexation.

Canadian Television Airs Episode – Hawai‘i

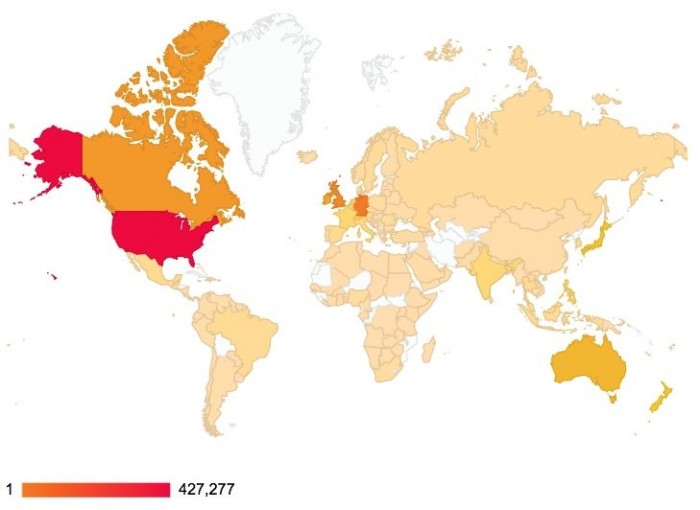

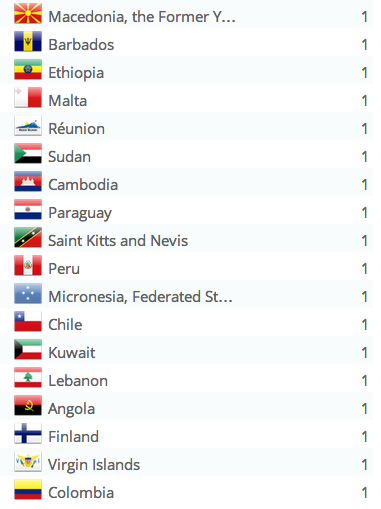

176 Countries Visiting Hawaiian Kingdom Blog

Since the Hawaiian Kingdom blog was launched in August 2012 there has been nearly half a million hits from 176 countries, which includes non-self-governing territories, e.g. French Polynesia, Guam, American Samoa, Macao, Hong Kong and the Northern Mariana Islands. The largest number of visits come from the United States at 427,227, followed by Germany at 1,932, and the United Kingdom at 1,255.

The highest number of visits on a single day was 5,709 on May 11, 2014, and the blog has averaged 2,500 visits per day. For the past 30 days there has been a total of 57,776 visits from the following countries.

Comprehensive Plan to Transition from Illegal Regime to Military Government

The United States has had its footprint in the Hawaiian Kingdom since U.S. troops unlawfully landed on Hawaiian territory on January 16, 1893, in order to secure protection for a puppet government, calling themselves the Committee of Safety. The puppet government was created by the U.S. diplomat John Stevens. The following day, Stevens extended de facto recognition to this small group of roughly 30 individuals calling themselves the provisional government and ordered the U.S. troops to protect them from arrest by the Hawaiian police force for treason. Their stated purpose was to seek annexation to the United States.

A treaty of annexation was signed in Washington, D.C. between the insurgency and President Benjamin Harrison on February 14, 1893 and submitted to the U.S. Senate for ratification. On March 4th, President Grover Cleveland replaced Harrison and after receiving a diplomatic protest from Queen Lili’uokalani on the 9th he removed the treaty from the Senate and initiated a presidential investigation into the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government. His investigator, James Blount, who was the former Chairman of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, reported “The American minister and the revolutionary leaders had determined on annexation to the United States, and had agreed on the part each was to act to the very end.” The investigation was completed on December 18, 1893 and determined the United States was responsible for the unlawful overthrow of a friendly government.

Negotiations took place between the Queen and the President’s diplomat, Albert Willis, in Honolulu beginning on November 13, 1893, and an agreement was reached on December 18th that obligated the United States to reinstate the Queen in her constitutional authority and thereafter the Queen to grant a pardon to the insurgents. This agreement, which under international law is a treaty, was not carried out. This allowed the illegal regime to hire American mercenaries in order continue to intimidate and coerce government officials in the executive and judicial branches of the Hawaiian government to sign oaths of allegiance. This illegal regime changed its name to the so-called Republic of Hawai‘i on July 4, 1894.

On August 12, 1898, the United States disguised the military occupation during the Spanish-American War as if Hawai‘i ceded its territory and sovereignty by a treaty. There is no treaty. According to Marek’s Identity and Continuity of States in Public International Law, p. 110, “a disguised annexation aimed at destroying the independence of the occupied State, represents a clear violation of the rule preserving the continuity of the occupied State.”

The regime’s name has since been changed to the Territory of Hawai‘i in 1900 and then to the State of Hawai‘i in 1959. For the past 121 years the United States footprint has never left the islands and because of its deliberate failure to administer the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom through its illegal regimes since 1893 it has created a state of emergency that called for a comprehensive plan for transition from an illegal regime to a military government before the occupation can come to an end.

When a State is illegally occupying territory and has established an illegal regime, all official acts of the occupying State are null and void except for the registration of births, marriages and deaths. This is referred to as the Namibia exception, which was formulated by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) during the existence of an illegal regime established by South Africa when it unlawfully occupied Namibia. Examples of official acts include, but are not limited to, the function of notaries, registration of land titles, decisions by judicial and administrative courts, enactment of laws, licensing, etc. In his comment on the Namibia exception, the United Nations Secretary General noted that the determination of any legal validity of South Africa’s illegal presence would be the prerogative of the Namibian Legislative Assembly.

When a country’s territory is occupied by a foreign State, acts of a political nature are suspended throughout the duration of the occupation, which includes the right to vote. And when neutral territory is occupied by a belligerent State, the 1907 Hague Convention IV is not applied in its entirety. According Takahashi’s International Law Applied to the Russo-Japanese War, p. 251, and acknowledged by the U.S. Army Judge Advocate General (JAG) School’s Text no. 11, Law of Belligerent Occupation, p. 4, the only sections of the Hague Convention IV that apply to neutral territory under occupation by a belligerent State are:

Article 42—on the elements and sphere of military occupation;

Article 43—on the duty of the occupant to respect the laws in force in the country;

Article 46—concerning family honour and rights, the lives of individuals and their private property as well as their religious convictions and the right of public worship;

Article 47—on prohibiting pillage;

Article 49—on collecting the taxes;

Article 50—on collective penalty, pecuniary or otherwise;

Article 51—on collecting contributions;

Article 53—concerning properties belonging to the state or private individuals, which may be useful in military operations;

Article 54—on material coming from neutral states; and

Article 56—on the protection of establishments consecrated to religious, warship, charity, etc.

The occupant State’s “authority may be exercised in every field of government activity, executive, administrative, legislative and judicial,” as stated in the JAG’s Law of Belligerent Occupation, p. 38. “The occupant’s laws and regulations which find justification in military necessity or in his duty to maintain law and safety are legitimate under international law. Conversely, the acts of the occupant which have no reasonable relation to military necessity or the maintenance of order and safety are illegitimate.”

The United States use of illegal regimes to further entrench the disguised occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom is a direct violation of the laws of occupation and general international law. As such, it has drawn to the forefront the Namibia exception with regard to these violations, which renders every executive, administrative, legislative and judicial acts done by these regimes since January 17, 1893 to be invalid and void except for the registration of births, marriages and deaths. As the national and international communities are becoming aware of the profound legal and economic ramifications of the United States’ failure to abide by international law, the situation in the Hawaiian Kingdom is cataclysmic.

In response to a course heading to unrivaled calamity for the country and the world at large, the acting Council of Regency could find no other recourse but to decree provisional laws for the Hawaiian Kingdom on October 10, 2014 in light of the United States’ violation of international law and the law of occupation for the past 121 years. Included in the decree of provisional laws are those laws having emanated from the Hawaiian legislatures that were convened under the so-called Bayonet Constitution of July 6, 1887, which was the beginning of the insurgency. This so-called constitution was not proclaimed in accordance with Hawaiian constitutional law.

For a detailed analysis of the formation of the acting Council of Regency under the doctrine of necessity download “The Continuity of the Hawaiian State and the Legitimacy of the acting Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom.”

As a result of an effective American occupation, the acting Council of Regency does not have the capacity or the ability to enforce the provisional laws proclaimed under the doctrine of necessity. It is the United States that must carry this out. Failure to do so would only lead to economic ruination for not only the United States, but also for the Hawaiian Kingdom and its citizenry, being the victims of these egregious and criminal violations.

This is analogous to the United States having stepped on a land mine called Hawai‘i’s sovereignty on January 16, 1893. That foot has not moved since then, and for the United States to remove its foot from this land mine and begin to comply with the international laws of occupation would consequently admit to the illegality of 121 years and the land mine would blow up legally and economically. That explosion would not only severely injure the United States, but it could also do the same to the Hawaiian Kingdom and everyone residing in these Islands to include those who are legally and economically tied to these islands who live abroad. What’s needed is a means by which the weight of the United States as a government could be replaced by an equal weight so that the land mine can be disarmed. Only a government could do such a thing, and in this case it could only be done by the acting Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom, which itself was established in 1997 by the doctrine of necessity. The decree of provisional laws is this equal weight needed in order for the United States to remove its foot and begin to administer the laws of the occupied State according to the 1907 Hague Convention IV and the 1949 Geneva Convention IV.

The decree of provisional laws is a practical and comprehensive plan for transition from an illegal regime to a military government that relies on international law, which includes treaties, international customs, general principles of law recognized around the world, the decisions of international courts, scholarly writing, and the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom. It is not intended to end the occupation, but rather to bring compliance to the laws of occupation. It is the responsibility of the acting government to ensure implementation of these provisional laws by any and all lawful means.

A State of War Between Hawai‘i and the United States Now at 121 years

Under international law, war does not only apply to belligerent States, but also applies to neutral States whose territories have been invaded and occupied by one of the belligerents in its course of war with the other belligerent. According to Oppenheim’s International Law (7th ed.), p. 685, “hostilities against a neutral [State] on the part of either belligerent are acts of war, and not mere violations of neutrality. Thus the German attack on Belgium in 1914, to enable German troops to march through Belgian territory and attack France, created war between Germany and Belgium.” While Belgium was occupied by Germany from 1914-1918, Belgium was, for the purposes of international law, also at war with Germany during the occupation.

By the 1839 Treaty of London, Great Britain, Austria, France, the German Confederation, Russia, and the Netherlands recognized Belgium as an independent and perpetual neutral State. Under international law, a neutral State cannot wage war but is limited to the defense of its territory. During World War I, Belgium’s neutrality was violated by Germany in its war against France.