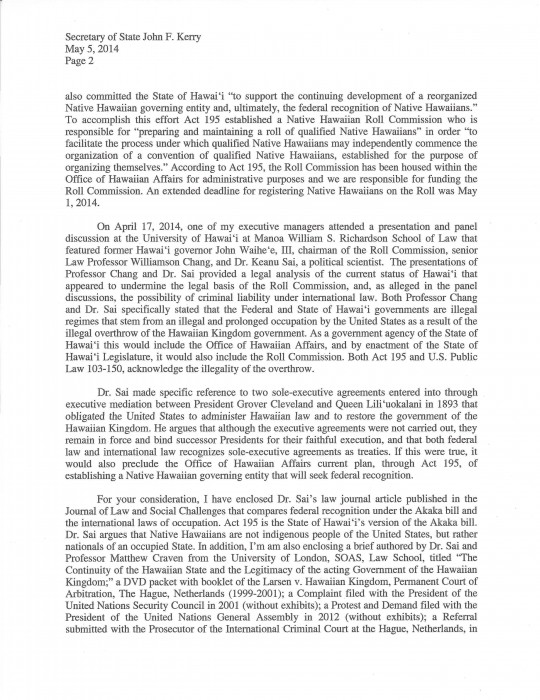

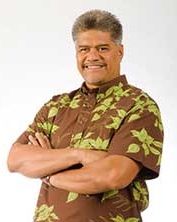

Here follows the letter Office of Hawaiian Affairs CEO Kamana‘opono Crabbe submitted to the Department of State dated May 5, 2014. What will be gleaned from the letter itself is that the CEO was well within his vested power to seek clarity on the question of the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

Category Archives: Treaties

What Have the Office of Hawaiian Affairs Trustees Done—It Doesn’t Make Sense or Does It?

After the Office of Hawaiian Affairs CEO Dr. Kamana‘opono Crabbe submitted a formal request to Secretary of State John Kerry seeking clarification on the legal status of Hawai‘i under international law, all nine OHA Trustees yesterday signed a letter to the Secretary of State, stating:

After the Office of Hawaiian Affairs CEO Dr. Kamana‘opono Crabbe submitted a formal request to Secretary of State John Kerry seeking clarification on the legal status of Hawai‘i under international law, all nine OHA Trustees yesterday signed a letter to the Secretary of State, stating:

“We understand that you received a letter from Office of Hawaiian Affairs Chief Executive Officer Kamana‘opono M. Crabbe, PhD dated May 5, 2014. The contents of that letter do not reflect the position of the Board of Trustees of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs or the position of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. That letter is hereby rescinded.”

Did the Trustees even read Dr. Crabbe’s letter? How do you rescind a letter that seeks clarification for risk management purposes. You can’t. The only person that can rescind the letter is the CEO himself, and only when the risks identified have been found to not be risks in the first place. Another word for this is fiduciary duty.

This morning’s front page article in the Star-Advertiser reported that Trustee Chairwoman Colette Machado said “Crabbe exceeded his authority as chief executive officer that requires him to consult the board on such matters.” Is Dr. Crabbe’s request for clarification a management issue or a board issue. Does the CEO need Board approval to ask questions? What is the position of the Board of Trustees of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs? We don’t want clarification? The so-called rescind letter is not only odd, but it is disingenuous and has nothing to do with Dr. Crabbe’s letter. It also raises the question of who is pulling the strings.

This morning’s front page article in the Star-Advertiser reported that Trustee Chairwoman Colette Machado said “Crabbe exceeded his authority as chief executive officer that requires him to consult the board on such matters.” Is Dr. Crabbe’s request for clarification a management issue or a board issue. Does the CEO need Board approval to ask questions? What is the position of the Board of Trustees of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs? We don’t want clarification? The so-called rescind letter is not only odd, but it is disingenuous and has nothing to do with Dr. Crabbe’s letter. It also raises the question of who is pulling the strings.

After carefully reviewing Dr. Crabbe’s letter, he did not state or even imply that he was taking any position on whether or not the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist. He merely sought clarification on a legal issue that the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel is more than capable of answering. If there is any position taken by Dr. Crabbe its responsible management and the well-recognized principle “risk management.” His letter begins with:

“As the chief executive officer and administrator for the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, being a governmental agency of the State of Hawai‘i, the law places on me, as a fiduciary, strict standards of diligence, responsibility and honesty. My executive staff, as public officials, carry out the policies and directives of the Trustees of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs in the service of the Native Hawaiian community. We are responsible to take care, through all lawful means, that we apply the best skills and diligence in the servicing of this community. It is in this capacity and in the interest of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs I am submitting this communication and formal request.”

The performance of risk assessment begins with identification of risks. Once the risk or risks have been determined the management can choose to avoid the risk, reduce the risk, share the risk or retain the risk. After the option is made, management then calls for a plan for contingencies, create safeguards, and, lastly, to monitor.

Dr. Crabbe has clearly taken the path to avoid the risk by seeking clarification from the State Department and the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel.

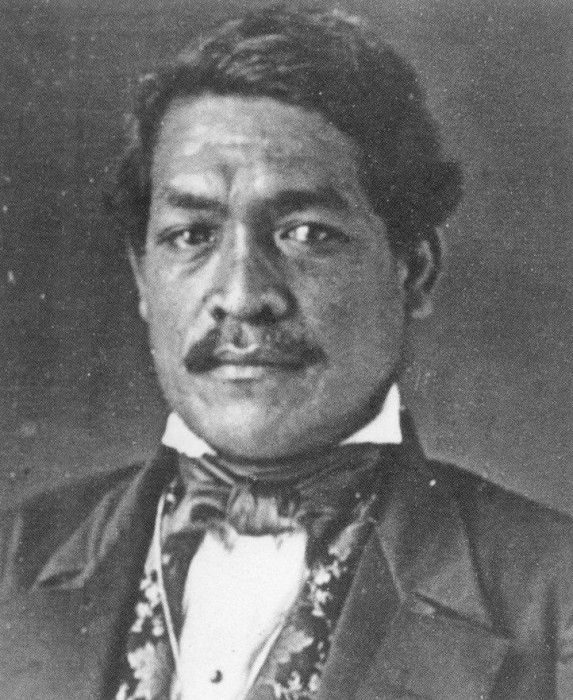

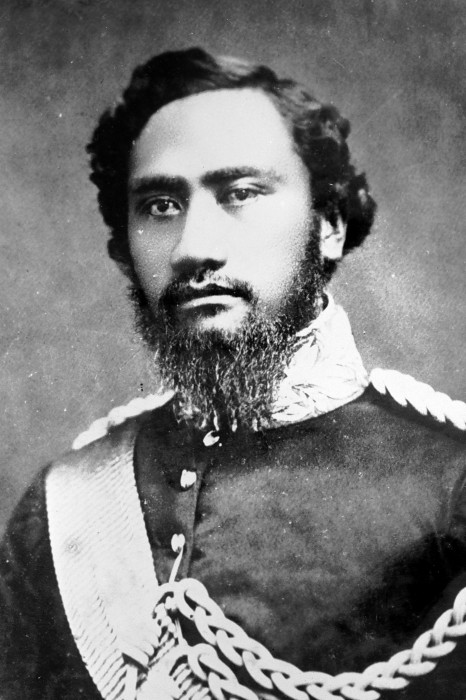

From his letter he specifically states the risks began to surface when one of his executive managers attended a presentation and panel discussion at the University of Hawai‘i Law School featuring former Hawai‘i governor John Waihe‘e, III, senior Law Professor Williamson Chang and political scientist Dr. Keanu Sai. The law student chapter of the American Constitutional Society sponsored the presentation. Dr. Crabbe provided Secretary of State Kerry an online link to view the video of the law school presentation.

https://vimeo.com/92655472

Crabbe wrote, “The presentations of Professor Chang and Dr. Sai provided a legal analysis of the current status of Hawai‘i that appeared to undermine the legal basis of the Roll Commission, and, as alleged in the panel discussions, the possibility of criminal liability under international law. Both Professor Chang and Dr. Sai specifically stated that the Federal and State of Hawai‘i governments are illegal regimes that stem from an illegal and prolonged occupation by the United States as a result of the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government. As a government agency of the State of Hawai‘i this would include the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, and by enactment of the State of Hawai‘i Legislature, it would also include the Roll Commission. Both Act 195 and U.S. Public Law 103-150, acknowledges the illegality of the overthrow.”

Here are some quotes from senior Law Professor Chang:

Here are some quotes from senior Law Professor Chang:

“The power of the United States, over the Hawaiian islands, and the jurisdiction of the United States in the State of Hawai’i, by its own admissions, by its own laws, doesn’t exist. And so that means that ever since the 1898 annexation of Hawai’i, by a Joint Resolution, they say, we have been living a myth.” (3:01 min/sec.)

“If you don’t have legal power over a territory, you’re governing without jurisdiction.” (4:20 min/sec.)

“…there’s no treaty between the United States and Hawai‘i by which Hawai‘i was acquired by the United States…” (4:41 min/sec.)

“A joint resolution, as an act of Congress, cannot acquire another country …If the United States could acquire Hawai‘i then the House of Nobles and the Legislative Assembly of Hawai‘i could acquire the United States.” (4:54 min/sec.)

“If two sovereigns are equal … one cannot acquire the other by its own laws.” (5:17 min/sec.)

“If Congress cannot, by Joint Resolution in 1898, acquire Hawai‘i unilaterally, it cannot do so in 1959.” (9:42 min/sec.)

“So in short, the United States by its own hands admits that it didn’t acquire the Hawaiian Islands, and all those Hawaiians, who have been saying the United States doesn’t have jurisdiction, have been right.” (11:25 min/sec.)

“So the annexation, that we all admit that nothing can be achieved without the United States going along with it, that’s the 900 lbs. elephant in the room. But we have to come in with the best leverage we have, and the best leverage we have is a hundred years of being lied to, being misrepresented, being told that we were part of the United States, and that has been legally false.” (17:19 min/sec.)

“…we’re all in this boat together in this journey of knowledge, and when I talk about the state of emergency, being the United States, how it is able to govern us for a hundred years without putting guns to our heads, it’s us. We’re the problem, the law school is the problem. Why, because judges and lawyers have a duty of candor and truth. Judges, on their own, have to tell the courts, tell the attorneys that there is no jurisdiction. It’s a duty of zealous representation for attorneys to present the best defense, and isn’t it the best defense that there’s no jurisdiction.” (1:36:41 hr/min/sec.)

Here some quotes from political scientist Dr. Keanu Sai:

Here some quotes from political scientist Dr. Keanu Sai:

“Without a treaty, the United States has enacted “internal laws,” by its Congress, imposed in Hawai‘i…1898 Joint Resolution of Annexation, 1900 Territorial Act, 1959 Statehood Act, 1993 Joint Resolution of Apology for the 1893 Overthrow” (1:37:17 hr/min/sec.)

“Now the first and foremost restriction imposed by international law upon a State is that it may not exercise its power in any form in the territory of another State. In this sense jurisdiction is certainly territorial; it cannot be exercised by a State outside of its territory except by virtue of a permissive rule derived from international custom or from a convention.” (1:36:53 hr/min/sec.)

“military occupation confers upon the invading force the means of exercising control for the period of occupation. It does not transfer the sovereignty to the occupant, but simply the authority or power to exercise some of the rights of sovereignty.” (1:13:19 hr/min/sec.)

Even former governor and chairman of the Native Hawaiian Roll Commission Waihe‘e was in agreement with Dr. Sai’s analysis that Hawai‘i is not a part of the United States. Waihe‘e told the audience:

Even former governor and chairman of the Native Hawaiian Roll Commission Waihe‘e was in agreement with Dr. Sai’s analysis that Hawai‘i is not a part of the United States. Waihe‘e told the audience:

“I have absolutely no doubt that Hawai‘i is in an illegal occupation, I have absolutely no doubt. I mean, you’ve got to be illiterate not to finally get to that point.” (1:19:04 hr/min/sec.)

Can a CEO of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs take this lightly, especially when the Chairman of the Native Hawaiian Roll Commission himself stated he has no doubt that Hawai‘i is occupied and that you’ve got to be illiterate to not see it. Dr. Crabbe correctly states:

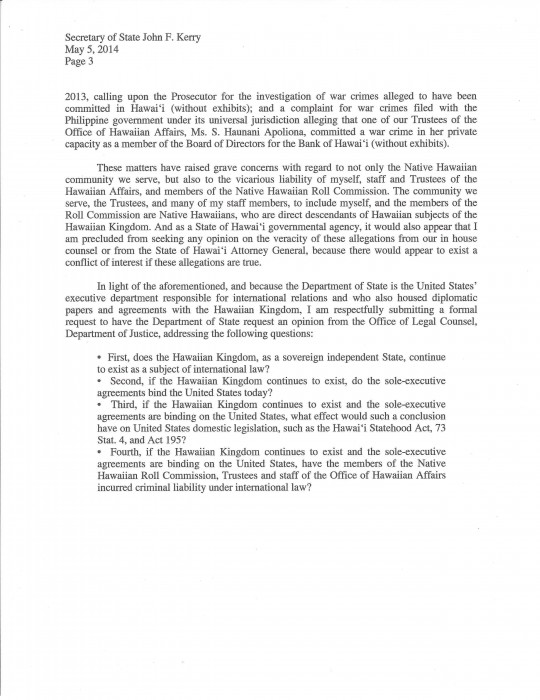

“These matters have raised grave concerns with regard to not only the Native Hawaiian community we serve, but also to the vicarious liability of myself, staff and Trustees of the Hawaiian Affairs, and members of the Native Hawaiian Roll Commission. The community we serve, the Trustees, and many of my staff members, to include myself, and the members of the Roll Commission are Native Hawaiians, who are direct descendants of Hawaiian subjects of the Hawaiian Kingdom. And as a State of Hawai‘i governmental agency, it would also appear that I am precluded from seeking any opinion on the veracity of these allegations from our in house counsel or from the State of Hawai‘i Attorney General, because there would appear to exist a conflict of interest if these allegations are true.”

Dr. Crabbe then provided the questions he’s seeking to be answered as part of the process of risk management.

• First, does the Hawaiian Kingdom, as a sovereign independent State, continue to exist as a subject of international law?

• Second, if the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist, do the sole-executive agreements bind the United States today?

• Third, if the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist and the sole-executive agreements are binding on the United States, what effect would such a conclusion have on United States domestic legislation, such as the Hawai‘i Statehood Act, 73 Stat. 4, and Act 195?

• Fourth, if the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist and the sole-executive agreements are binding on the United States, have the members of the Native Hawaiian Roll Commission, Trustees and staff of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs incurred criminal liability under international law?”

Dr. Crabbe’s conclusion in his letter clearly speaks to risk management and his determination to avoid the risk of criminal liability under international law. He stated, “While I await the opinion from the Office of Legal Counsel, I will be requesting approval from the Trustees of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs that we refrain from pursuing a Native Hawaiian governing entity until we can confirm that the Hawaiian Kingdom, as an independent sovereign State, does not continue to exist under international law and that we, as individuals, have not incurred any criminal liability in this pursuit.”

At no point has Dr. Crabbe taken a position for the Office of Hawaiian Affairs and nor has he taken a position of whether the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist. He’s seeking clarification from a federal agency who is more than capable of providing the answers. As chief executive officer, Dr. Crabbe is responsible for the protection of the staff at the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, which includes the Trustees, and to the Native Hawaiian community OHA serves. The Trustees’ so-called rescind letter is a blatant attempt to undermine the very duty Dr. Crabbe was appointed to do as the CEO of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. The Trustees’ do not manage the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, the CEO does.

The irony is that Dr. Crabbe’s request for clarification is to protect the Trustees, even from themselves.

Hawai‘i News Now – Letter seeking clarity on Hawaiian Kingdom status is rescinded

HONOLULU (HawaiiNewsNow) – Does the Kingdom of Hawai’i exist today — and are we all subject to its rules? Those questions have triggered an internal dispute within the Office of Hawaiian Affairs.

OHA’s Chief Executive Officer created a firestorm Friday when word spread he sent a letter to the Secretary of State asking for an official opinion on whether the Hawaiian Kingdom still exists as an independent sovereign state under international law. Problem is, it appears no one else at OHA knew about or agreed with the letter, stirring an internal controversy that has raised concerns the inquiry could derail or delay Kana’iolowalu nation-building efforts.

Officials confirm the letter was quietly sent out on Monday by OHA CEO Dr. Kamana’opono Crabbe, in which he requested a formal legal opinion from the Justice Department.

“I will be requesting approval from the Trustees of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs that we refrain from pursuing a Native Hawaiian governing entity until we can confirm that the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent sovereign State, does not continue to exist under international law and that we, as individuals, have no incurred any criminal liability in this pursuit,” Crabbe wrote.

OHA Chair Colette Machado tells Hawaii News Now she and fellow trustees only learned of the letter Friday afternoon.

“Our whole goal is to establish a Native Hawaiian governing entity and we are very close in achieving that. The Trustees fully support this, that’s why we’re quite surprised — how did our Chief Executive Officer not understand this by sending the letter to the state Department especially to the Secretary John Kerry? That’s why we had to respond quickly on a unanimous position to rescind that letter, because it is not an official position of OHA,” Machado said by phone from Washington, D.C., where she and Crabbe are attending a meeting about the upcoming World Conference on Indigenous Peoples at the invitation of the Department of State.

All nine trustees signed off on retracting the letter, which Machado confirms has already been sent to the Department of Justice.

“I want to assure the Hawaiian people that the Board of Trustees has not changed its position towards facilitating a process to reorganize a Native Hawaiian governing entity,” Machado said.

Native Hawaiian Roll Commission Chair, former Governor John Waihe’e, says he was also surprised by the letter.

“For all of us that know our history, there’s no doubt in our mind that the government of Queen Lili’uokalani was illegally overthrown and that the United States annexation of Hawaii was not done properly, was not done legally. In fact, this was admitted by the United States Congress when they passed the resolution — the apology resolution — in 1993. Any of us that know our history, know that we don’t need to ask anybody, know whether or not any of these things were proper — what we need to do is go about organizing ourselves and beginning to assert our own self governance. I don’t know what motivated Kamana’opono to do this, but personally I think it’s sort of disempowering. It’s a disempowering tactic to ask for permission to pursue your own destiny,” Waihe’e said.

More than 125,000 people have signed up for Kana’iolowalu to pursue a Native Hawaiian self-governing entity, an effort which OHA is financing.

“That’s more people than all the labor unions in Hawai’i combined,” said Waihe’e. “As far as we’re concerned, the Roll Commission is concerned, we’re still proceeding forward.”

Hawaii News Now was unable to reach Dr. Crabbe directly Friday. Officials confirm he scheduled a press conference for next week Monday to explain the inquiry, but now that the trustees have rescinded that letter it’s unclear if the press conference will still be happening.

To view Dr. Crabbe’s request letter, click here.

Washington Times: Agency seeks clarity on Hawaiian Kingdom status

HONOLULU (AP) – Office of Hawaiian Affairs CEO Kamanaopono Crabbe says he will seek approval from the agency’s trustees to refrain from pursuing a Native Hawaiian governing entity.

Crabbe says the agency would put nation building efforts on hold until officials are able to confirm the Hawaiian Kingdom doesn’t continue to exist under international law.

Crabbe outlined his proposal in a May 5 letter to Secretary of State John Kerry. The agency released a copy of the letter Friday.

The letter says an analysis from scholars alleging federal and state governments are illegal regimes has raised concerns. The analysis says OHA trustees and Native Hawaiian Roll Commission members may be criminally liable under international law.

Crabbe is asking the State Department to request an opinion from the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel.

Associated Press: Office of Hawaiian Affairs seeks clarity on status of Hawaiian Kingdom under international law

HONOLULU — Office of Hawaiian Affairs CEO Kamanaopono Crabbe says he will seek approval from the agency’s trustees to refrain from pursuing a Native Hawaiian governing entity.

Crabbe says the agency would put nation building efforts on hold until officials are able to confirm the Hawaiian Kingdom doesn’t continue to exist under international law.

Crabbe outlined his proposal in a May 5 letter to Secretary of State John Kerry. The agency released a copy of the letter Friday.

The letter says an analysis from scholars alleging federal and state governments are illegal regimes has raised concerns. The analysis says OHA trustees and Native Hawaiian Roll Commission members may be criminally liable under international law.

Crabbe is asking the State Department to request an opinion from the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel.

State of Hawai‘i Government Official Requests from U.S. State Department Legal Opinion on the Current Status of Hawai‘i under International Law

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

MAY 09, 2014

WASHINGTON, D.C. (May 9, 2014) – The Office of Hawaiian Affairs top executive submitted a formal request with the U.S. Department of State requesting a legal opinion from the U.S. Attorney General’s Office of Legal Counsel addressing the legal status of the Hawai‘i under international law.

WASHINGTON, D.C. (May 9, 2014) – The Office of Hawaiian Affairs top executive submitted a formal request with the U.S. Department of State requesting a legal opinion from the U.S. Attorney General’s Office of Legal Counsel addressing the legal status of the Hawai‘i under international law.

The Office of Legal Counsel drafts legal opinions of the U.S. Attorney General and also provides its own written opinions and oral advice in response to requests from the various agencies of the Executive Branch, which includes the Department of State.

Trustees and staff of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs are in Washington, D.C., at the invitation of the Department of State for a consultation with representatives of the federal government, federally recognized tribes and other indigenous peoples of the United States on May 9. The topic of the meeting is the World Conference on Indigenous Peoples, to be held at the United Nations, September 22-23, 2014. The meeting will take place at the U.S. Department of State, 23rd Street entrance, between C and D Streets, N.W., Washington, D.C.

In a letter addressed to Secretary of State John F. Kerry, OHA Chief Executive Officer Dr. Kamana‘opono Crabbe, described his request as a very important question that needs to be answered from an agency that is not only qualified but authorized to answer, saying that it is addressing very grave concerns of OHA’s activities in its efforts toward nation building.

In a letter addressed to Secretary of State John F. Kerry, OHA Chief Executive Officer Dr. Kamana‘opono Crabbe, described his request as a very important question that needs to be answered from an agency that is not only qualified but authorized to answer, saying that it is addressing very grave concerns of OHA’s activities in its efforts toward nation building.

“As the chief executive officer and administrator for the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, being a governmental agency of the State of Hawai‘i, the law places on me, as a fiduciary, strict standards of diligence, responsibility and honesty,” Crabbe said. “My executive staff, as public officials, carry out the policies and directives of the Trustees of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs in the service of the Native Hawaiian community. We are responsible to take care, through all lawful means, that we apply the best skills and diligence in the servicing of this community.”

Crabbe explained the action taken was prompted when one of his staff attended a presentation and panel discussion at the William S. Richardson School of Law on April 17, 2014 that featured former Hawai‘i Governor John Waihe‘e, III, Chairman of the Native Hawaiian Roll Commission, senior Law Professor Williamson Chang, and Dr. Keanu Sai, a political scientist. Click here to view a video of the Law School presentation and panel discussion.

“The presentations of Professor Chang and Dr. Sai provided a legal analysis of the current status of Hawai‘i that appeared to undermine the legal basis of the Roll Commission, and, as alleged in the panel discussions, the possibility of criminal liability under international law. Both Professor Chang and Dr. Sai specifically stated that the Federal and State of Hawai‘i governments are illegal regimes that stem from an illegal and prolonged occupation by the United States as a result of the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government.” Crabbe said. “As a government agency of the State of Hawai‘i this would include the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, and by enactment of the State of Hawai‘i Legislature, it would also include the Roll Commission. Both Act 195 and U.S. Public Law 103-150, acknowledges the illegality of the overthrow.”

According to Crabbe, “These matters have raised grave concerns with regard to not only the Native Hawaiian community we serve, but also to the vicarious liability of myself, staff and Trustees of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, and members of the Native Hawaiian Roll Commission. The community we serve, the Trustees, and many of my staff members, to include myself, and the members of the Roll Commission are Native Hawaiians, who are direct descendants of Hawaiian subjects of the Hawaiian Kingdom.”

Crabbe said he wanted to seek an opinion on the veracity of these allegations from its in house counsel or from the State of Hawai‘i Attorney General, but felt he was prevented because there would appear to be a conflict of interest if these allegations were true.

In his letter, Crabbe said, “because the Department of State is the United States’ executive department responsible for international relations and who also housed diplomatic papers and agreements with the Hawaiian Kingdom, I am respectfully submitting a formal request to have the Department of State request an opinion from the Office of Legal Counsel, Department of Justice, addressing the following questions:

• First, does the Hawaiian Kingdom, as a sovereign independent State, continue to exist as a subject of international law?

• Second, if the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist, do the sole-executive agreements bind the United States today?

• Third, if the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist and the sole-executive agreements are binding on the United States, what effect would such a conclusion have on United States domestic legislation, such as the Hawai‘i Statehood Act, 73 Stat. 4, and Act 195?

• Fourth, if the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist and the sole-executive agreements are binding on the United States, have the members of the Native Hawaiian Roll Commission, Trustees and staff of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs incurred criminal liability under international law?”

A press conference is scheduled for Monday, May 12, at 10:00 a.m. when OHA’s Chief Executive Officer Dr. Crabbe returns from Washington, D.C.

Click here to download the request letter.

IMPORTANT NOTE: Dr. Crabbe’s letter specifically states:

“For your consideration, I have enclosed Dr. Sai’s law journal article published in the Journal of Law and Social Challenges that compares federal recognition under the Akaka bill and the international laws of occupation. Act 195 is the State of Hawai‘i’s version of the Akaka bill. Dr. Sai argues that Native Hawaiians are not indigenous people of the United States, but rather nationals of an occupied State. In addition, I’m am also enclosing a brief authored by Dr. Sai and Professor Matthew Craven from the University of London, SOAS, Law School, titled “The Continuity of the Hawaiian State and the Legitimacy of the acting Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom;” a DVD packet with booklet of the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, Permanent Court of Arbitration, The Hague, Netherlands (1999-2001); a Complaint filed with the President of the United Nations Security Council in 2001 (without exhibits); a Protest and Demand filed with the President of the United Nations General Assembly in 2012 (without exhibits); a Referral submitted with the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court at the Hague, Netherlands, in 2013, calling upon the Prosecutor for the investigation of war crimes alleged to have been committed in Hawai‘i (without exhibits); and a complaint for war crimes filed with the Philippine government under its universal jurisdiction alleging that one of our Trustees of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, Ms. S. Haunani Apoliona, committed a war crime in her private capacity as a member of the Board of Directors for the Bank of Hawai‘i (without exhibits).”

“While I await the opinion from the Office of Legal Counsel, I will be requesting approval from the Trustees of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs that we refrain from pursuing a Native Hawaiian governing entity until we can confirm that the Hawaiian Kingdom, as an independent sovereign State, does not continue to exist under international law and that we, as individuals, have not incurred any criminal liability in this pursuit.”

# # #

Media Contact: Garett Kamemoto

Communications Manager

808-594-1982

garettk@oha.org

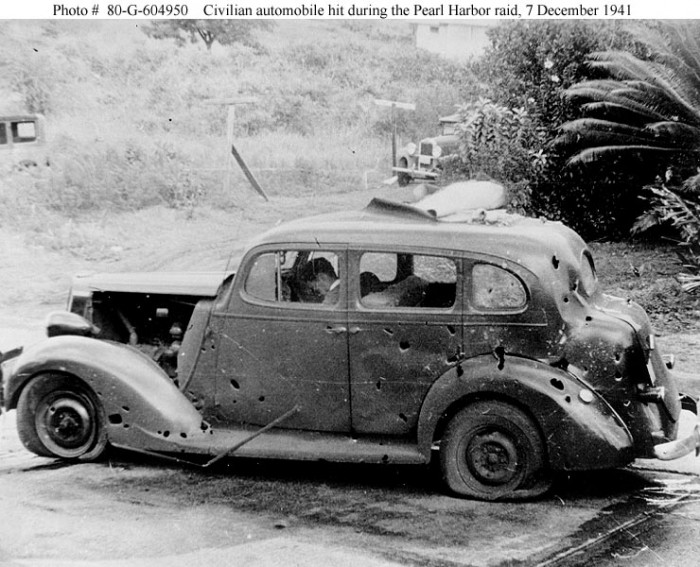

Swiss Foreign Ministry Meets With Hawaiian Envoy in Bern

Due to the war crimes that continue to be committed with impunity by the State of Hawai‘i, an illegal regime, against innocent civilians, the acting government of the Hawaiian Kingdom has temporarily refrained from pursuing its proceedings at the International Court of Justice and has decided to focus its attention to secure a Protecting Power pursuant to the Fourth Geneva Convention (GCIV) and the Additional Protocol I (API). A Protecting Power is a State that ensures compliance of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States to the provisions of the GCIV and API, with particular focus on the protection of civilians.

As a State Party to the GCIV and AP, article 5(1) of the API, states, “It is the duty of the Parties to a conflict from the beginning of that conflict to secure the supervision and implementation of the Conventions and of this Protocol by the application of the system of Protecting Powers, including inter alia the designation and acceptance of those Powers, in accordance with the following paragraphs.” And according to article 5(3) of the API, if a Protecting Power has not been designated, “the International Committee of the Red Cross…shall offer its good offices to the Parties to the conflict with a view to the designation without delay of a Protecting Power to which the Parties to the conflict consent.”

On December 18, 2013, at its headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) was formally requested to assist the Hawaiian Kingdom in securing a Protecting Power in accordance with the GCIV and API. In this pursuit, the acting government has been in the process of securing a meeting with the Swiss government in order to formally request that it be a Protecting Power and to work with the ICRC. The Swiss government has a long history of serving as a mediator to international conflicts and did serve as a protecting power in the past. A meeting was secured on March 26, 2014, and the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs’ Directorate of International Law in Bern, Switzerland, received the acting government’s Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary. Negotiations to secure Switzerland as a Protecting Power for the illegal and prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom have begun.

Hawai‘i and the Namibia Exception

According to international law, the United States Federal government and the United States’ State of Hawai‘i government operating within the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom are illegal regimes. Article 43 of the Hague Convention, IV, mandates that the occupying State, the United States, to administer the laws of the occupied State, the Hawaiian Kingdom. According to Professor Marco Sassoli, Article 43 of the Hague Regulations and Peace Operations in the Twenty-first Century, p. 5, “Article 43 does not confer on the occupying power any sovereignty over the occupied territory. The occupant may therefore not extend its own legislation over the occupied territory nor act as a sovereign legislator. It must, as a matter of principle, respect the laws in force in the occupied territory at the beginning of the occupation.”

These illegal regimes are and have been administering United States law and not Hawaiian law in an attempt to conceal the prolonged and illegal occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom. According to Dr. Yaël Ronen, Status of Settlers Implanted by Illegal Regimes under International Law (2008), p. 2, “Illegal regimes often transfer of their own populations or populations loyal to them in the territory, and subsequently grant these populations residence or nationality in the territory. This is done in order to change the demographic composition of the territory under dispute and thereby solidify the regime.”

When another country’s government is operating within the territory of another country without title or sovereignty, every official action taken by that regime is illegal and void except for its registration of births, marriages and deaths. This is called the “Namibia exception,” which is a decision by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in 1971 called the Legal Consequences for States of the Continued Presence of South Africa in Namibia (South West Africa) notwithstanding Security Council Resolution 276 (1970).

In 1966, the United Nations General Assembly passed resolution 2145 (XXI) that terminated South Africa’s administration of Namibia, formerly known as South West Africa, a former German colony. This resulted in Namibia coming under the administration of the United Nations, but South Africa refused to withdraw from Namibian territory and consequently the situation transformed into an illegal occupation. As a former German colony, Namibia became a mandate territory under the administration of South Africa after the close of the First World War.

Addressing the legal consequences arising for South Africa’s refusal to leave Namibia, the ICJ stated that by “occupying the Territory without title, South Africa incurs international responsibilities arising from a continuing violation of an international obligation,” and that all countries, whether a member of the United Nations or not were “under an obligation to recognize the illegality and invalidity of South Africa’s continued presence in Namibia and to refrain from lending any support or any form of assistance to South Africa with reference to its occupation of Namibia.” The ICJ, however, clarified that “non-recognition should not result in depriving the people of Namibia of any advantages derived from international cooperation.

The conduct of an illegal regime during occupation is limited and confined to the international laws of occupation and to the principle of ex injuria ius non oritur—where unlawful acts cannot be the source of lawful rights. According to Ronen, p. 39, “Opposite the principle of ex injuria jus non oritur operates the principle ex factis ius oritur. It mandates that acts of the illegal regime may have legal consequences despite the illegality and status of the regime that performed them.” Ronen explains, “In other words, the general invalidity of domestic acts carried out under an illegal regime is qualified where such invalidity would act to the detriment of the inhabitants of the territory. This is the Namibia exception.” The ICJ in the Namibia case explained, “the principle ex injuria jus non oritur dictates that acts which are contrary to international law cannot become a source of legal acts for the wrongdoer… To grant recognition to illegal acts or situation will tend to perpetuate it and be benefitial to the state which has acted illegally.”

The focus of the Namibia exception is to protect the interests of the nationals of the occupied State and not to entrench the authority of an illegal regime. The validity of any other official acts of an illegal regime other than the registration of births, marriages and deaths must not serve “to the detriment of the inhabitants of the territory” being occupied and must not be seen to further “entrench the authority of an illegal regime.”

Hawai‘i and the Crimean Conflict

Today on CNN’s coverage of the “Crisis in Ukraine” at 3:31pm (Eastern Time), news anchor Brooke Baldwin made a very interesting comment. Baldwin stated, “Ukrainian officials believe 30,000 Russian troops are now there in that small peninsula about the size of Hawai‘i.” This is a very interesting comparison by CNN to make reference to Hawai‘i with the Crimean conflict, especially when it would appear that CNN has no knowledge, or do they, of Hawai‘i’s direct link to Crimea regarding Hawaiian neutrality and the correlation between the argument of Russian intervention and United States intervention in the Hawaiian Kingdom. CNN also reported that Russia warns U.S. that threatened sanctions will “boomerang.”

Today on CNN’s coverage of the “Crisis in Ukraine” at 3:31pm (Eastern Time), news anchor Brooke Baldwin made a very interesting comment. Baldwin stated, “Ukrainian officials believe 30,000 Russian troops are now there in that small peninsula about the size of Hawai‘i.” This is a very interesting comparison by CNN to make reference to Hawai‘i with the Crimean conflict, especially when it would appear that CNN has no knowledge, or do they, of Hawai‘i’s direct link to Crimea regarding Hawaiian neutrality and the correlation between the argument of Russian intervention and United States intervention in the Hawaiian Kingdom. CNN also reported that Russia warns U.S. that threatened sanctions will “boomerang.”

What is at the center of the Ukrainian crisis is “intervention,” and whether or not international law has been violated. The United States says yes, but Russia says no. The international law on intervention is clearly prohibitive, but there are exceptions according to Oppenheim, International Law, vol. 1, (7th ed. 1948), p. 274. The two exceptions that appear to be in line with the Crimean conflict are, first, where restrictions on a treaty are not being complied with, and, second, the rights of citizens of the intervening State are being threatened.

Restrictive Treaty

The treaty that the United States consistently makes reference to as to why Russian actions in the Crimea is a violation of international law is the 1997 Friendship Treaty between Ukraine and Russia. At the ceremonies in Kiev, Russian President Boris Yeltsin, declared, “We respect and honor the territorial integrity of Ukraine.” A State’s territorial integrity, however, is protected by international law and not just by a treaty. International law provides that “the territorial integrity and political independence of the State are inviolable.” This treaty does not appear to be President Vladimir Putin’s justification for Russian action in the Crimea. Instead, Putin appears to refer to the treaty that centers on the Russian Naval Base at Sevastopol.

In the aftermath of the breakup of the Soviet Union, Russia negotiated the fate of its military bases that were located outside of Russian territory. Russia’s Naval Base at Sevastopol in Crimea dates back to 1783 when the Russian Prince Grigory Potemkin founded the port city. In 1997, Russia and Ukraine signed a Partition Treaty whereby Russia would maintain its naval base after purchasing 81.7% of Ukraine’s naval ships for $526.5 million dollars as reported by RT News. This treaty was ratified in 1999 by both governments. The treaty allows the Russian Black Sea Fleet to remain in Crimea until 2042. Russia claims that the new government in Kiev is not legitimate and its anti-Russian rhetoric a threat to its Naval Base at Sevastopol and the maintenance of the 1997 Partition Treaty. According to international law, this would be a justification for intervention and it would appear that Putin is correct in that Russia is complying with international law.

At this stage, Russia has not deployed its troops into Ukraine even though the Russian Parliament authorized Putin the authority to do so. What has taken place in Crimea is not an invasion, but rather actions taken by Russian troops that were already stationed in Crimea at its Naval Base in Sevastopol. The 1997 Partition Treaty allows for 25,000 Russian troops, 24 artillery systems with a caliber smaller than 100 mm, 132 armored vehicles, and 22 military planes on Crimean territory. It appears that Russia has used its military force in Crimea to ensure that its Naval Base will not be seized. Although, these troops did not have any Russian insignia in order to identify a chain of command, they are Russian citizens who wore military garb. Putin has stated that, “Russian forces in Crimea are only acting to protect Russian military assets. It is ‘citizens’ defense groups,’ not Russian forces, who have seized infrastructure and military facilities in Crimea.” If Putin ordered the Russian Forces in Crimea to seize Ukrainian infrastructure and military facilities, it would be intervention, but by stating they are citizens defense groups, it is a clever way to sidestep intervention. But intervention would be justified if Russia feels that its 1997 Partition Treaty is being threatened, which would allow Russia to preemptively neutralize Ukrainian military posts in Crimea before they can attack the naval base.

Protection of Citizens

As reported by Aljazeera, “Unhappy with the outcome of the protests in the capital and alarmed at the rise of Ukrainian nationalist groups in Kiev, many ethnic Russians in Crimea, who make up almost 60 percent of the population here, have been protesting and calling for Russia to come to their aid—with some even going as far as demanding their neighbor immediately absorb the territory.” International law does not allow for citizens to have the authority to call for intervention, but the intervening State may feel it has a duty to intervene and will unilaterally do so. It is, however, a point of contention as to the extent of the threat to ethnic Russians, or if there is any threat at all to warrant Russian intervention.

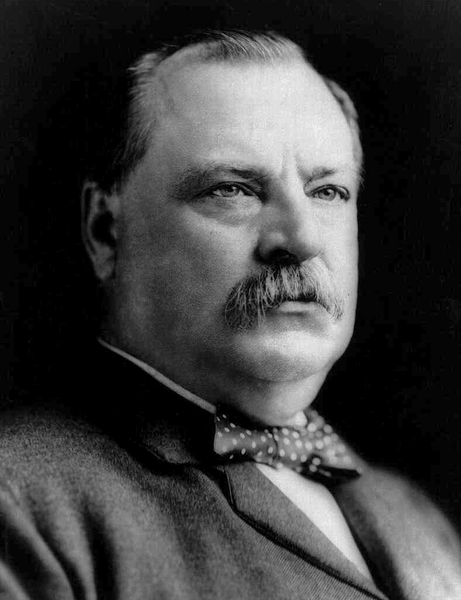

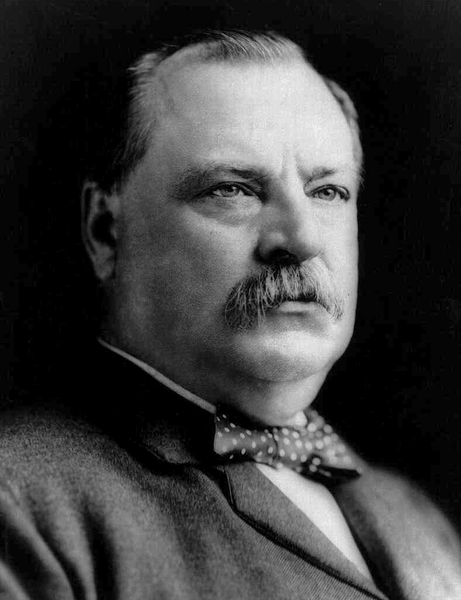

What is lacking in the Crimean conflict is an impartial investigation into the crisis where legally relevant facts could be gathered and conclusions made in accordance with international law. For the Hawaiian crisis in 1893, President Benjamin Harrison refused to do an investigation that was called for by Queen Lili‘uokalani, because he was intent on annexing the Hawaiian Kingdom for military purposes. It was his successor in office, Grover Cleveland, that did the investigation in accordance with international law. In his message to Congress, Cleveland stated,

“The law of nations is founded upon reason and justice, and the rules of conduct governing individual relations between citizens or subjects of a civilized state are equally applicable as between enlightened nations. The considerations that international law is without a court for its enforcement, and that obedience to its commands practically depends upon good faith, instead of upon the mandate of a superior tribunal, only give additional sanction to the law itself and brand any deliberate infraction of it not merely as a wrong but as a disgrace. A man of true honor protects the unwritten word which binds his conscience more scrupulously, if possible, than he does the bond a breach of which subjects him to legal liabilities; and the United States in aiming to maintain itself as one of the most enlightened of nations would do its citizens gross injustice if it applied to its international relations any other than a high standard of honor and morality. On that ground the United States can not properly be put in the position of countenancing a wrong after its commission any more than in that of consenting to it in advance. On that ground it can not allow itself to refuse to redress an injury inflicted through an abuse of power by officers clothed with its authority and wearing its uniform; and on the same ground, if a feeble but friendly state is in danger of being robbed of its independence and its sovereignty by a misuse of the name and power of the United States, the United States can not fail to vindicate its honor and its sense of justice by an earnest effort to make all possible reparation.”

“The law of nations is founded upon reason and justice, and the rules of conduct governing individual relations between citizens or subjects of a civilized state are equally applicable as between enlightened nations. The considerations that international law is without a court for its enforcement, and that obedience to its commands practically depends upon good faith, instead of upon the mandate of a superior tribunal, only give additional sanction to the law itself and brand any deliberate infraction of it not merely as a wrong but as a disgrace. A man of true honor protects the unwritten word which binds his conscience more scrupulously, if possible, than he does the bond a breach of which subjects him to legal liabilities; and the United States in aiming to maintain itself as one of the most enlightened of nations would do its citizens gross injustice if it applied to its international relations any other than a high standard of honor and morality. On that ground the United States can not properly be put in the position of countenancing a wrong after its commission any more than in that of consenting to it in advance. On that ground it can not allow itself to refuse to redress an injury inflicted through an abuse of power by officers clothed with its authority and wearing its uniform; and on the same ground, if a feeble but friendly state is in danger of being robbed of its independence and its sovereignty by a misuse of the name and power of the United States, the United States can not fail to vindicate its honor and its sense of justice by an earnest effort to make all possible reparation.”

“These principles apply to the present case with irresistible force when the special conditions of the Queen’s surrender of her sovereignty are recalled. She surrendered not to the provisional government, but to the United States. She surrendered not absolutely and permanently, but temporarily and conditionally until such time as the facts could be considered by the United States. Furthermore, the provisional government acquiesced in her surrender in that manner and on those terms, not only by tacit consent, but through the positive acts of some members of that government who urged her peaceable submission, not merely to avoid bloodshed, but because she could place implicit reliance upon the justice of the United States, and that the whole subject would be finally considered at Washington.”

According to international law there is a recognized legal maxim, ex injuria jus non oritur, whereby a State cannot claim valid legal results from an illegal act committed against another State. The International Court of Justice, in its Advisory Opinion on Namibia (June 21, 1971), explained, “the principle ex injuria jus non oritur dictates that acts which are contrary to international law cannot become a source of legal acts for the wrongdoer… To grant recognition to illegal acts or situation will tend to perpetuate it and be benefitial to the state which has acted illegally.”

United States Intervention in Hawai‘i and the Russian Intervention in Crimea

On March 4, 2014, CNN covered a speech by U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry in Kiev, Ukraine. Kerry stated, “They would have you believe that ethnic Russians and Russian bases are threatened. They would have you believe the Kiev was trying to destabilize Crimea or that Russian actions were legal or legitimate because Crimean leaders invited intervention. And as everybody knows the soldiers in Crimea, at the instruction of their government, had stood their ground, had never fired a shot, never issued one provocation.”

On March 4, 2014, CNN covered a speech by U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry in Kiev, Ukraine. Kerry stated, “They would have you believe that ethnic Russians and Russian bases are threatened. They would have you believe the Kiev was trying to destabilize Crimea or that Russian actions were legal or legitimate because Crimean leaders invited intervention. And as everybody knows the soldiers in Crimea, at the instruction of their government, had stood their ground, had never fired a shot, never issued one provocation.”

Kerry accused Russia of doing exactly what the United States did to the Hawaiian  Kingdom in January 1893. Unlike the Crimean dispute, however, the Hawaiian dispute was settled by U.S. President Grover Cleveland after he initiated an investigation into the overthrow of the Hawaiian government

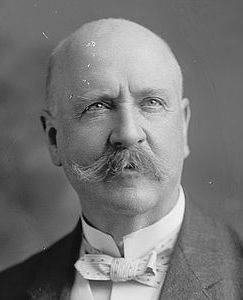

Kingdom in January 1893. Unlike the Crimean dispute, however, the Hawaiian dispute was settled by U.S. President Grover Cleveland after he initiated an investigation into the overthrow of the Hawaiian government at the request of Queen Lili‘uokalani, Hawaiian Head of State, in March 1893. At the center of the investigation were the actions taken by U.S. Minister Plenipotentiary John Stevens

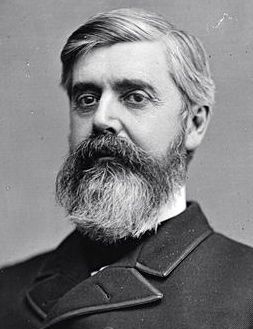

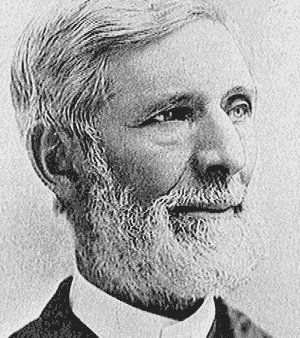

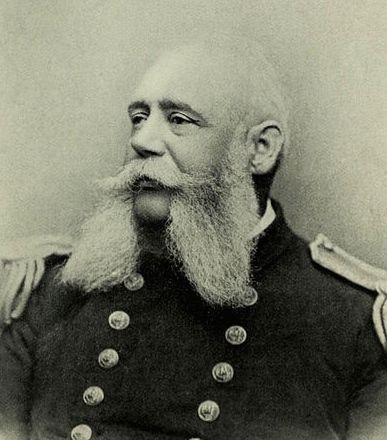

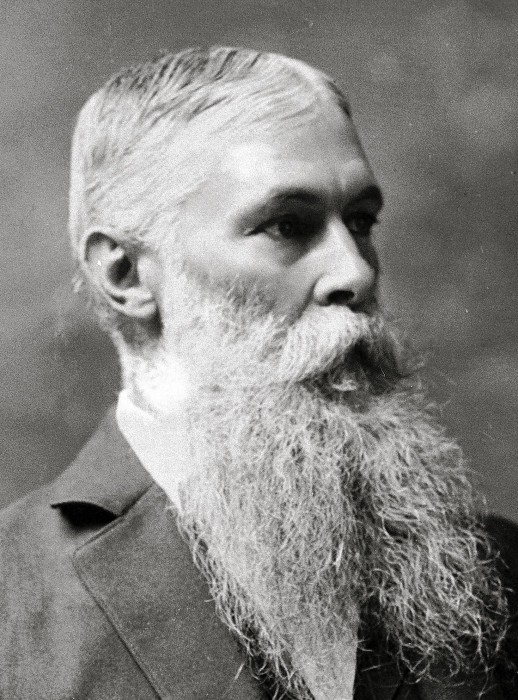

at the request of Queen Lili‘uokalani, Hawaiian Head of State, in March 1893. At the center of the investigation were the actions taken by U.S. Minister Plenipotentiary John Stevens  and the commander of U.S. troops aboard the U.S.S. Boston anchored in Honolulu Harbor, Captain Gilbert Wiltse. The intervention occurred during President Benjamin Harrison’s administration. The President appointed James Blount as Special Commissioner who submitted reports between April and July 1893 to U.S. Secretary of State Walter Gresham. The investigation was concluded by Gresham on October 18, 1893. President Cleveland notified the Congress of the conclusion of the investigation by presidential message on December 18, 1893, while negotiations were still taking place with the Queen in Honolulu.

and the commander of U.S. troops aboard the U.S.S. Boston anchored in Honolulu Harbor, Captain Gilbert Wiltse. The intervention occurred during President Benjamin Harrison’s administration. The President appointed James Blount as Special Commissioner who submitted reports between April and July 1893 to U.S. Secretary of State Walter Gresham. The investigation was concluded by Gresham on October 18, 1893. President Cleveland notified the Congress of the conclusion of the investigation by presidential message on December 18, 1893, while negotiations were still taking place with the Queen in Honolulu.

The investigation determined that the United States unlawfully intervened in the internal affairs of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and that its diplomat and troops were directly responsible for the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian government. Gresham recommended to President Cleveland that the Hawaiian government must be restored and compensation must be provided. This prompted executive mediation between President Cleveland and Queen Lili‘uokalani to settle the dispute and by exchange of notes an executive agreement, called the “Agreement of Restoration,” was concluded whereby the President committed to the restoration of the Hawaiian government and the Queen, thereafter, to grant amnesty to the insurgents. The President did not carry out the international agreement because of political wrangling in the Congress, and President Cleveland’s successor, William McKinley, unilaterally seized the Hawaiian Islands during the Spanish-American War on August 12, 1898. Hawai‘i has been under an illegal and prolonged occupation ever since.

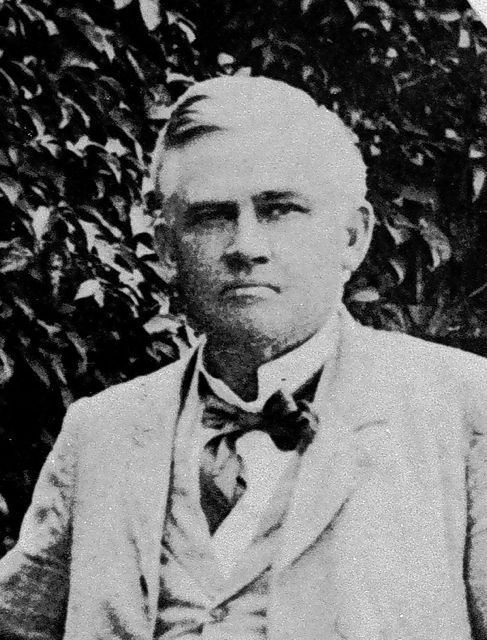

Here follows Gresham’s report to President Cleveland regarding U.S. intervention in Hawai‘i that took place under President Benjamin Harrison’s administration.

Here follows Gresham’s report to President Cleveland regarding U.S. intervention in Hawai‘i that took place under President Benjamin Harrison’s administration.

Department of State,

Washington, October 18, 1893

The President:

The full and impartial reports submitted by the Hon. James H. Blount, your special commissioner to the Hawaiian Islands, established the following facts:

Queen Liliuokalani announced her intention on Saturday, January 14, 1893, to proclaim a new constitution, but the opposition of her ministers and other induced her to speedily change her purpose and make public announcement of that fact.

At a meeting in Honolulu, late on the afternoon of that day, a so-called committee of public safety, consisting of thirteen men, being all or nearly all who were present, was appointed “to consider the situation and devise ways and means for the maintenance of the public peace and the protection of life and property,” and at a meeting of this committee on the 15th, or the forenoon of the 16th of January, it was resolved amongst other things that a provisional government be created “to exist until terms of union with the United States of America have been negotiated and agreed upon.” At a mass meeting which assembled at 2 p.m. on the last named day, the Queen and her supporters were condemned and denounced, and the committee was continued and all its act approved.

Later the same afternoon the committee addressed a letter to John L. Stevens, the American minister at Honolulu, stating that the lives and property of the people were in peril and appealing to him and the United States forces at his command for assistance. This communication concluded “we are unable to protect ourselves without aid, and therefore hope for the protection of the United States forces.” On receipt of this letter Mr. Stevens requested

American minister at Honolulu, stating that the lives and property of the people were in peril and appealing to him and the United States forces at his command for assistance. This communication concluded “we are unable to protect ourselves without aid, and therefore hope for the protection of the United States forces.” On receipt of this letter Mr. Stevens requested  Capt. Wiltse, commander of the U.S.S. Boston, to land a force “for the protection of the United States legation, United States consulate, and to secure the safety of American life and property.” The well armed troops, accompanied by two gatling guns, were promptly landed and marched through the quiet streets of Honolulu to a public hall, previously secured by Mr. Stevens for their accommodation. This hall was just across the street form the government building, and in plain view of the Queen’s palace. The reason for thus locating the military will presently appear. The governor of the Island immediately addressed to Mr. Stevens a communication protesting against the act as an unwarranted invasion of Hawaiian soil and reminding him that the proper authorities had never denied permission to the naval forces of the United States to land for drill or any other proper purpose.

Capt. Wiltse, commander of the U.S.S. Boston, to land a force “for the protection of the United States legation, United States consulate, and to secure the safety of American life and property.” The well armed troops, accompanied by two gatling guns, were promptly landed and marched through the quiet streets of Honolulu to a public hall, previously secured by Mr. Stevens for their accommodation. This hall was just across the street form the government building, and in plain view of the Queen’s palace. The reason for thus locating the military will presently appear. The governor of the Island immediately addressed to Mr. Stevens a communication protesting against the act as an unwarranted invasion of Hawaiian soil and reminding him that the proper authorities had never denied permission to the naval forces of the United States to land for drill or any other proper purpose.

About the same time the Queen’s minister of foreign affairs sent a note to Mr. Stevens asking why the troops had been landed and informing him that the proper authorities were able and willing to afford full protection to the American legation and all American interests in Honolulu. Only evasive replies were sent to these communications.

While there were no manifestations of excitement or alarm in the city, and the people were ignorant of the contemplated movements, the committee entered the Government building, after first ascertaining that it was unguarded, and read a proclamation declaring that the existing Government was overthrown and a Provisional Government established in its place, “to exist until terms of union with the United States of America have been negotiated and agreed upon.” No audience was present when the proclamation was read, but during the reading 40 to 50 men, some of them indifferently armed, entered the room. The executive and advisory councils mentioned in the proclamation at once addressed a communication to Mr. Stevens, informing him that the monarchy had been abrogated and a provisional government established. This communication concluded:

Such Provisional Government has been proclaimed, is now in possession of the Government departmental buildings, the archives, and the treasury, and is in control of the city. We hereby request that you will, on behalf of the United States, recognize it as the existing de facto Government of the Hawaiian Islands and afford to it the moral support of your Government, and, if necessary, the support of American troops to assist in preserving the public peace.

On receipt of this communication, Mr. Stevens immediately recognized the new Government, and, in a letter addressed to Sanford B. Dole, its President, informed him that he had done so. Mr. Dole replied:

On receipt of this communication, Mr. Stevens immediately recognized the new Government, and, in a letter addressed to Sanford B. Dole, its President, informed him that he had done so. Mr. Dole replied:

Government Building,

Honolulu, January 17, 1893

Sir: I acknowledge receipt of your valued communication of this day, recognizing the Hawaiian Provisional Government, and express deep appreciation of the same.

We have conferred with the ministers of the late Government, and have made demand upon the marshal to surrender the station house. We are not actually yet in possession of the station house, but as night is approaching and our forces may be insufficient to maintain order, we request the immediate support of the United States forces, and would request that the commander of the United States forces take command of our military forces, so that they may act together for the protection of the city.

Respectfully, yours,

Sanford B. Dole,

Chaiman Executive Council.

His Excellency John L. Stevens,

United States Minister Resident.

Note of Mr. Stevens at the end of the above communication.

“The above request not complied with.”

Stevens.

The station house was occupied by a well armed force, under the command of a resolute capable, officer. The same afternoon the Queen, her ministers, representatives of the Provisional Government, and other held a conference at the palace. Refusing to recognize the new authority or surrender to it, she was informed that the Provisional Government had the support of the American minister, and, if necessary, would be maintained by the military force of the United States then present; that any demonstration on her part would precipitate a conflict with that force; that she could not, with hope of success, engage in war with the United States, and that resistance would result in a useless sacrifice of life. Mr. Damon, one of the chief leader of the movement, and afterwards vice-president of the Provisional Government, informed the Queen that she could surrender under protest and her case would be considered later at Washington. Believing that, under the circumstances, submission was a duty, and that her case would be fairly considered by the President of the United States, the Queen finally yielded and sent to the Provisional Government the paper, which reads:

“I, Lili‘uokalani, by the grace of God and under the constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Queen, do hereby solemnly protest against any and all acts done against myself and the constitutional Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom by certain persons claiming to have established a provisional government of and for this Kingdom.

That I yield to the superior force of the United States of America whose Minister Plenipotentiary, His Excellency John L. Stevens, has caused United States troops to be landed at Honolulu and declared that he would support the provisional government.

Now to avoid any collision of armed forces, and perhaps the loss of life, I do this under protest and impelled by said force yield my authority until such time as the Government of the United States shall, upon facts being presented to it, undo the action of its representatives and reinstate me in the authority which I claim as the Constitutional Sovereign of the Hawaiian Islands.”

When this paper was prepared at the conclusion of the conference, and signed by the Queen and her ministers, a number of persons, including one or more representatives of the Provisional Government, who were still present and understood its contents, by their silence, at least, acquiesced in its statements, and, when it was carried to President Dole, he indorsed upon it, “Received from the hands of the late cabinet this 17th day of January, 1893,” without challenging the truth of any of its assertions. Indeed, it was not claimed on the 17th day of January, or for some time thereafter, by any of the designated officers of the Provisional Government or any annexationist that the Queen surrendered otherwise than as stated in her protest.

In his dispatch to Mr. Foster of January 18, describing the so-called revolution, Mr. Stevens says:

The committee of public safety forthwith took possession of the Government building, archives, and treasury, and installed the Provisional Government at the head of the respective departments. This being an accomplished fact, I promptly recognized the Provisional Government as the de facto government of the Hawaiian Islands.

In Secretary Foster’s communication of February 15 to the President, laying before him the treaty of annexation, with the view to obtaining the advice and consent of the Senate thereto, he says:

At the time the Provisional Government took possession of the Government building no troops or officers of the United States were present or took any part whatever in the proceedings. No public recognition was accorded to the Provisional Government by the United States minister until after the Queen’s abdication, and when they were in effective possession of the Government building, the archives, the treasury, the barracks, the police station, and all the potential machinery of the Government.

Similar language is found in an official letter addressed to Secretary Foster on February 3 by the special commissioners sent to Washington by the Provisional Government to negotiate a treaty of annexation.

These statements are utterly at variance with the evidence, documentary and oral, contained in Mr. Blount’s reports. They are contradicted by declarations and letters of President Dole and other annexationists and by Mr. Stevens’s own verbal admissions to Mr. Blount. The Provisional Government was recognized when it had little other than a paper existence, and when the legitimate government was in full possession and control of the palace, the barracks, and the police station. Mr. Stevens’s well known hostility and the threatening presence of the force landed from the Boston was all that could then have excited serious apprehension in the minds of the Queen, her officers, and loyal supporters.

It is fair to say that Secretary Foster’s statements were based upon information which he had received from Mr. Stevens and the special commissioners, but I am unable to see that they were deceived. The troops were landed, not to protect American life and property, but to aid in overthrowing the existing government. Their very presence implied coercive measures against it.

In a statement given to Mr. Blount, by Admiral Skerret, the ranking naval officer at Honolulu, he says:

“If the troops were landed simply to protect American citizens and interests, they were badly stationed in Arion Hall, but if the intention was to aid the Provisional Government they were wisely stationed.”

This hall was so situated that the troops in it easily commanded the Government building, and the proclamation was real under the protection of American guns. At an early stage of the movement, if not at the beginning, Mr. Stevens promised the annexationists that as soon as they obtained possession of the Government building and there read a proclamation of the character above referred to, he would at once recognize them as a de facto government, and support them by landing a force from our war ship then in the harbor, and he kept that promise. This assurance was the inspiration on the movement, and without it the annexationists would not have exposed themselves to the consequences of failure. They relied upon no military force of their own, for they had none worthy of the name. The Provisional Government was established by the action of the American minister and the presence of the troops landed from the Boston, and its continued existence is due to the belief of the Hawaiians that if they made an effort to overthrow it, they would encounter the armed forces of the United States.

The earnest appeals to the American minister for military protection by the officers of that Government, after it had been recognized, show the utter absurdity of the claim that it was established by a successful revolution of the people of the Islands. Those appeals were a confession by the men who made them of their weakness and timidity. Courageous men, conscious of their strength and the justice of their cause, do not thus act. It is not now claimed that a majority of the people, having the right to vote under the constitution of 1887, ever favored the existing authority or annexation to this or any other country. They earnestly desire that the government of their choice shall be restored and its independence respected.

Mr. Blount states that while at Honolulu he did not meet a single annexationist who expressed willingness to submit the question to a vote of the people, nor did he talk with one on that subject who did not insist that if the Islands were annexed suffrage should be so restricted as to give complete control to foreigners or whites. Representative annexationists have repeatedly made similar statements to the undersigned.

The Government of Hawaii surrendered its authority under a threat of war, until such time only as the Government of the United States, upon the facts being presented to it, should reinstate the constitutional sovereign, and the Provisional Government was created “to exist until terms of union with the United States of America have been negotiated and agreed upon.” A careful consideration of the fact will, I think, convince you that the treaty which was withdrawn from the Senate for further consideration should not be resubmitted for its action thereon.

Should not the great wrong done to a feeble but independent State by an abuse of the authority of the United States be undone by restoring the legitimate government? Anything short of that will not, I respectfully submit, satisfy the demands of justice.

Can the United States consistently insist that other nations shall respect the independence of Hawaii while not respecting it themselves? Our Government was the first to recognize the independence of the Islands and it should be the last to acquire sovereignty over them by force and fraud.

Respectfully submitted.

W.Q. Gresham.

Hawaiian Neutrality and the Crimean Conflict

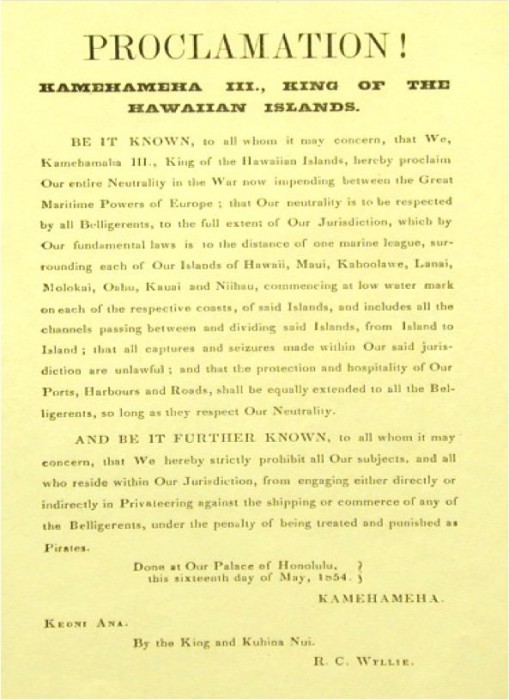

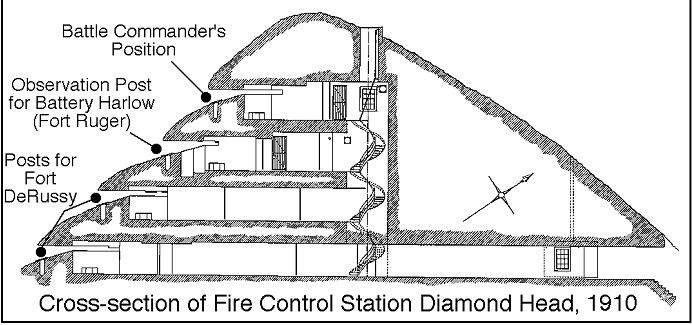

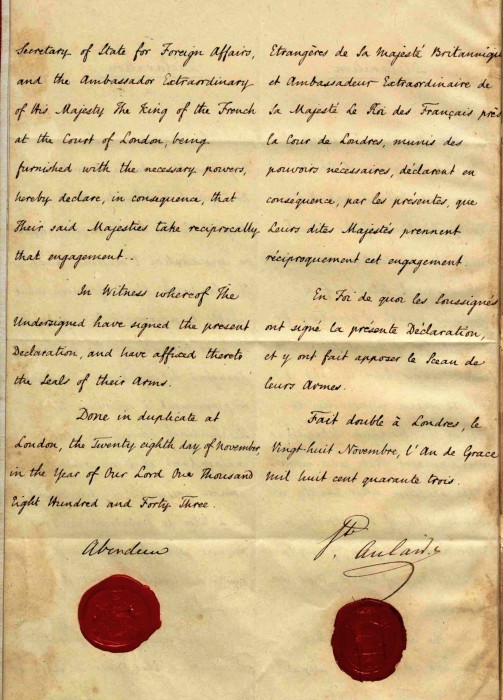

With the world’s attention on Russia and the Crimean Peninsula, people may not know that the Hawaiian Kingdom’s neutrality was prompted by hostilities that erupted between Russia and the European Powers during the Crimean War (1854-56). The Hawaiian Kingdom was also an active participant during the war in the development of the international laws on neutrality.

Russia’s Black Sea Naval Fleet is based at Sevastopol Naval Base in Crimea, which gives Russian naval vessels access to the Mediterranean and Aegean Seas, and further to the Atlantic Ocean. The two waterways that provide access from the Black Sea are Turkey’s Bosporus Straits and the Strait of the Dardanelles. Sevastopol Naval Base was also at the center of a war between Russia and the Ottoman Empire in 1853 over this access after Russia insisted that the Ottoman Turks recognize Russia’s right in the Middle East in order to protect Russian Orthodox in the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman’s refused and war broke out. On March 28, 1854, France and Great Britain joined the war on the side of the Ottoman Turks in order to prevent Russia’s increase in power over the region.

Naval battles between Russia and the French and British also spilled over to the Pacific Ocean where all three countries had naval and merchant ships. Battles were not confined to Crimea and the Caucasus, but were also fought in the Japan Seas, the Okhotsk Seas and in the North Pacific Ocean, and there was concern in Hawai‘i that it could reach the Hawaiian Islands. Just eleven years since Great Britain and France recognized the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State, King Kamehameha III, in Privy Council, declared the Hawaiian Kingdom to be a neutral State on May 16, 1854.

Naval battles between Russia and the French and British also spilled over to the Pacific Ocean where all three countries had naval and merchant ships. Battles were not confined to Crimea and the Caucasus, but were also fought in the Japan Seas, the Okhotsk Seas and in the North Pacific Ocean, and there was concern in Hawai‘i that it could reach the Hawaiian Islands. Just eleven years since Great Britain and France recognized the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State, King Kamehameha III, in Privy Council, declared the Hawaiian Kingdom to be a neutral State on May 16, 1854.

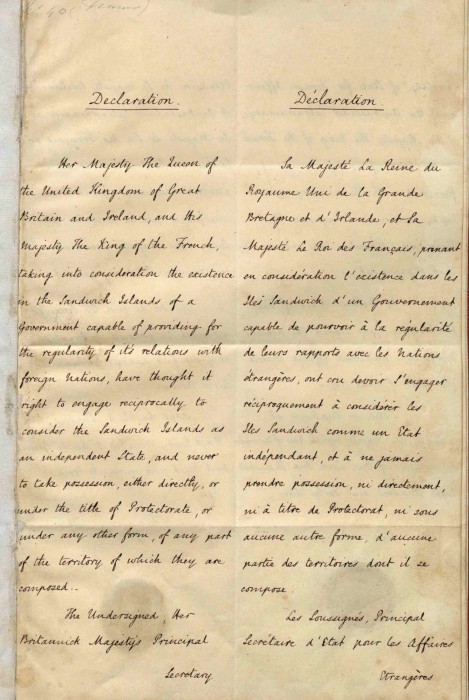

Prior to their impending involvement in the Crimean War, Great Britain and France each issued formal Declarations on March 28, 1854, and March 29, 1854, that declared neutral ships and goods would not be captured. Prior to this, international law did not afford protection for neutral ships carrying goods headed for the ports of countries who were at war. Under international law, these ships could be seized by either country’s naval vessels or by private ships that were commissioned by a country at war, which is called “privateering” and the goods seized were called “prizes.” The British and French diplomats that were posted in the Hawaiian Kingdom delivered both Declarations to the Hawaiian government.

On June 15, 1854, the Hawaiian Committee on the National Rights in regards to prizes had delivered its report during a meeting of the Privy Council in Honolulu. Robert C. Wyllie, Hawaiian Minister of Foreign Affairs, presented the committee report and the following resolution was passed and later made known to the countries engaged in the Crimean War.

On June 15, 1854, the Hawaiian Committee on the National Rights in regards to prizes had delivered its report during a meeting of the Privy Council in Honolulu. Robert C. Wyllie, Hawaiian Minister of Foreign Affairs, presented the committee report and the following resolution was passed and later made known to the countries engaged in the Crimean War.

“Resolved: That in the Ports of this neutral Kingdom, the privilege of Asylum is extended equally and impartially to the armed national vessels and prizes made by such vessels of all the belligerents, but no authority can be delegated by any of the Belligerents to try and declare lawful and transfer the property of such prizes within the King’s Jurisdiction; nor can the King’s Tribunals exercise any such jurisdiction, except in cases where His Majesty’s Neutral Jurisdiction and Sovereignty may have been violated by the Captain of any vessel within the bounds of that Jurisdiction.”

To broaden the international law of neutrality, the United States sought to get countries to agree thereby creating customary international law. On December 6, 1854, the U.S. diplomat assigned to the Hawaiian Kingdom, David L. Gregg, sent the following dispatch to the Hawaiian government regarding the recognition of neutral rights. The correspondence stated,

“I have the honor to transmit to you a project of a declaration in relation to neutral rights which my Government has instructed me to submit to the consideration of the Government of Hawaii, and respectfully to request its approval and adoption. As you will perceive it affirms the principles that free ships make free goods, and that the property of neutrals, not contraband of war, found on board of Enemies ships, is not confiscable. These two principles have been adopted by Great Britain and France as rules of conduct towards all neutrals in the present European war; and it is pronounced that neither nation will refuse to recognize them as rules of international law, and to conform to them in all time to come. The Emperor of Russia has lately concluded a convention with the United States, embracing these principles as permanent, and immutable, and to be scrupulously observed towards all powers which accede to the same.”

On January 12, 1855, the U.S. diplomat also sent another dispatch to the Hawaiian government that contained a copy of the July 22, 1854 Convention between the United States of America and Russia embracing certain principles in regard to neutral rights. After careful review of the U.S. President’s request, King Kamehameha IV in Privy Council, passed the following resolution on March 26, 1855.

On January 12, 1855, the U.S. diplomat also sent another dispatch to the Hawaiian government that contained a copy of the July 22, 1854 Convention between the United States of America and Russia embracing certain principles in regard to neutral rights. After careful review of the U.S. President’s request, King Kamehameha IV in Privy Council, passed the following resolution on March 26, 1855.

“Resolved: That the Declaration of accession to the principles of neutrality to which the President of the United States invites the King, is approved, and Mr. Wyllie is authorized to sign and seal the same and pass it officially to the Commissioner of the United States in reply to his dispatches of the 6th December and 12th January last.”

Following the Privy Council meeting on the same day, Robert C. Wyllie signed the Declaration of Accession to the Principles of Neutrality as requested by the United States President and delivered it to the U.S. diplomat David L. Gregg. The Declaration provided,

“And whereas His Majesty the King of the Hawaiian Islands, having considered the aforesaid invitation of the President of the United States, and the Rules established in the foregoing convention respecting the rights of neutrals during war, and having found such rules consistent with those proclaimed by Her Britannic Majesty in Her Declaration of the 28th March 1854, and by His Majesty the Emperor of the French in the Declaration of the 29th of the same month and year, as well as with Her Britannic Majesty’s order in Council of the 15th April same year, and with the peaceful and strictly neutral policy of this Kingdom as proclaimed by His late Majesty King Kamehameha III on the 11th May 1854, amplified and explained by Resolutions of His Privy Council of State of the 15th June and 17th July same year, His Majesty, by and with the advice of His Cabinet and Privy Council, has authorized the undersigned to declare in His name, as the undersigned now does declare that His Majesty accedes to the humane principles of the foregoing convention, in the sense of its III Article.”

On April 7, 1855, King Kamehameha IV opened the Legislative Assembly. In his speech he reiterated the Kingdom’s neutrality by stating:

“It is gratifying to me, on commencing my reign, to be able to inform you, that my relations with all the great Powers, between whom and myself exist treaties of amity, are of the most satisfactory nature. I have received from all of them, assurances that leave no room to doubt that my rights and sovereignty will be respected. My policy, as regards all foreign nations, being that of peace, impartiality and neutrality, in the spirit of the Proclamation by the late King, of the 16th May last, and of the Resolutions of the Privy Council of the 15th June and 17th July. I have given to the President of the United States, at his request, my solemn adhesion to the rule, and to the principles establishing the rights of neutrals during war, contained in the Convention between his Majesty the Emperor of all the Russias, and the United States, concluded in Washington on the 22nd July last.”

The actions taken by the governments of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Great Britain, France, Russia, and the United States of America relating to the development of the principles of international law on neutrality provided the necessary pretext for the leading European maritime powers to meet in Paris, after the Crimean War, and enter into a joint declaration that provided the following four principles: first, privateering is, and remains, abolished; second, the neutral flag covers enemy’s goods, with the exception of contraband of war; third, neutral goods, with the exception of contraband of war, are not liable to capture under the enemy’s flag; and, fourth, blockades, in order to be binding, must be effective, that is to say, maintained by a force sufficient really to prevent access to the coast of the enemy.

The Declarations and the 1854 Russo-American Convention represented the first recognition of the right of neutral States to conduct free trade without any hindrance from war. Stricter guidelines for neutrality were later established in the 1871 Anglo-American Treaty made during the wake of the American Civil War, whereby both States agreed to the following rules.

“First, to use due diligence to prevent the fitting out, arming, or equipping, within its jurisdiction, of any vessel which it has reasonable ground to believe is intended to cruise or to carry on war against a power with which it is at peace; and also to use like diligence to prevent the departure from its jurisdiction of any vessel intended to cruise or carry on war as above, such vessel having been specially adapted, in whole or in part, within such jurisdiction, to warlike use.

Second, not to permit or suffer either belligerent to make use of its ports or waters as the base of naval operations against the other, or for the purpose of the renewal or augmentation of military supplies or arms, or the recruitment of men.

Thirdly, to exercise due diligence in its own ports and waters, and, as to all persons within its jurisdiction, to prevent any violation of the foregoing obligations and duties.”

Newer and stricter rules for the conduct of neutral States were expounded upon in the 1874 Brussels Conference, and later these principles were codified in the Fifth and Thirteenth Hague Conventions of 1907, governing the rights and duties of neutral States in Land and Maritime warfare.

Hawaiian neutrality was also stated in its treaties with Sweden/Norway (1852, Article XV), Spain (1863, Article XXVI), Germany (1879, Article VIII) and Italy (1869, Additional Article). Article XV of the Hawaiian Treaty with Sweden/Norway states,

“All vessels bearing the flag of Sweden and Norway in time of war shall receive every possible protection, short of actual hostility, within the ports and waters of His Majesty the King of the Hawaiian Islands; and His Majesty the King of Sweden and Norway engages to respect in time of war the neutral rights of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and to use his good offices with all other powers, having treaties with His Majesty the King of the Hawaiian Islands, to induce them to adopt the same policy towards the Hawaiian Kingdom.”

Why the Hawaiian Kingdom, as an independent State, Continues to Exist