On March 4, 2014, CNN covered a speech by U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry in Kiev, Ukraine. Kerry stated, “They would have you believe that ethnic Russians and Russian bases are threatened. They would have you believe the Kiev was trying to destabilize Crimea or that Russian actions were legal or legitimate because Crimean leaders invited intervention. And as everybody knows the soldiers in Crimea, at the instruction of their government, had stood their ground, had never fired a shot, never issued one provocation.”

On March 4, 2014, CNN covered a speech by U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry in Kiev, Ukraine. Kerry stated, “They would have you believe that ethnic Russians and Russian bases are threatened. They would have you believe the Kiev was trying to destabilize Crimea or that Russian actions were legal or legitimate because Crimean leaders invited intervention. And as everybody knows the soldiers in Crimea, at the instruction of their government, had stood their ground, had never fired a shot, never issued one provocation.”

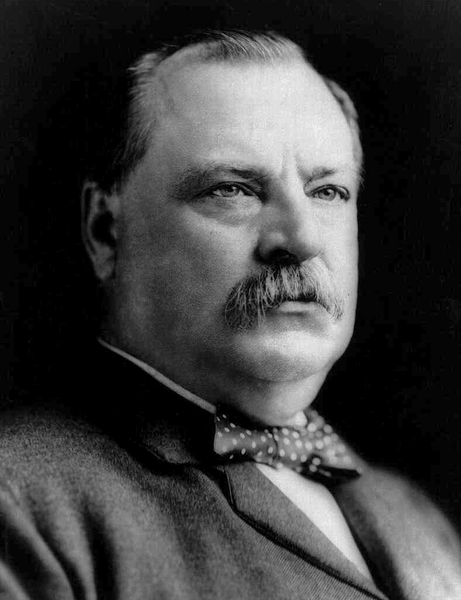

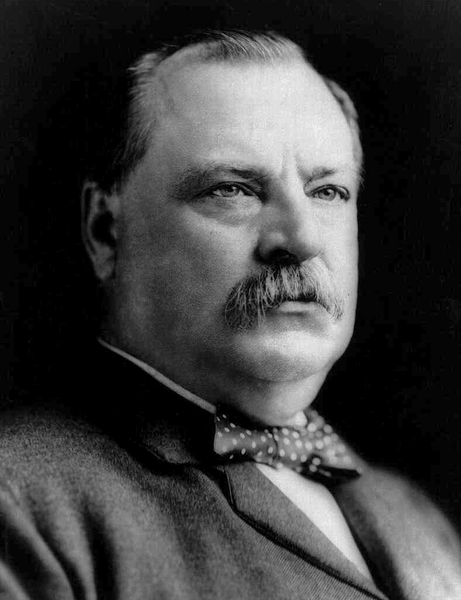

Kerry accused Russia of doing exactly what the United States did to the Hawaiian  Kingdom in January 1893. Unlike the Crimean dispute, however, the Hawaiian dispute was settled by U.S. President Grover Cleveland after he initiated an investigation into the overthrow of the Hawaiian government

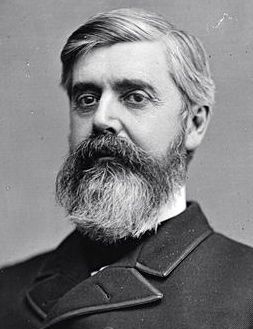

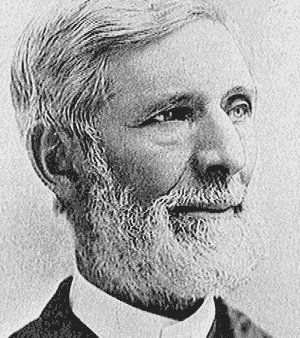

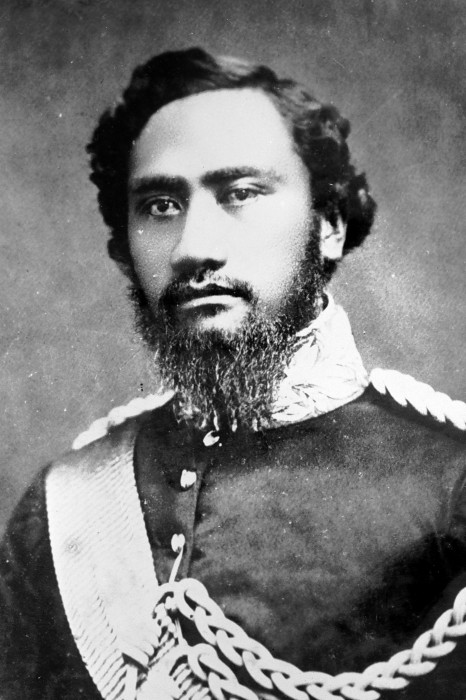

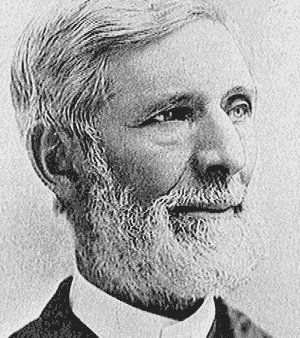

Kingdom in January 1893. Unlike the Crimean dispute, however, the Hawaiian dispute was settled by U.S. President Grover Cleveland after he initiated an investigation into the overthrow of the Hawaiian government at the request of Queen Lili‘uokalani, Hawaiian Head of State, in March 1893. At the center of the investigation were the actions taken by U.S. Minister Plenipotentiary John Stevens

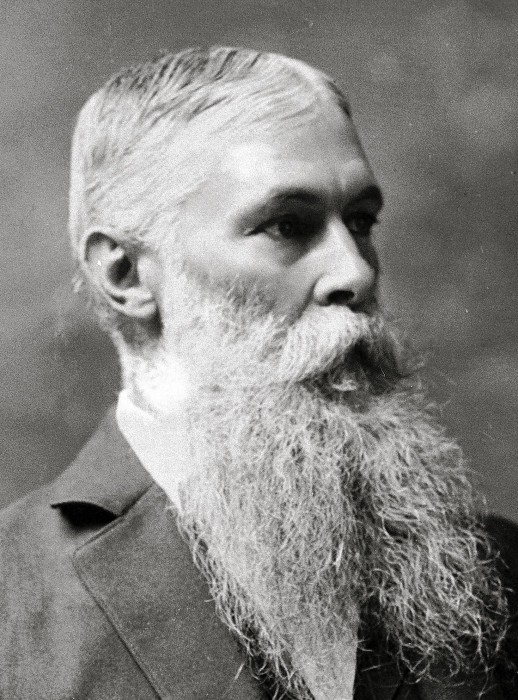

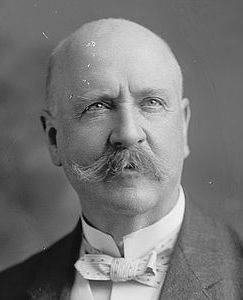

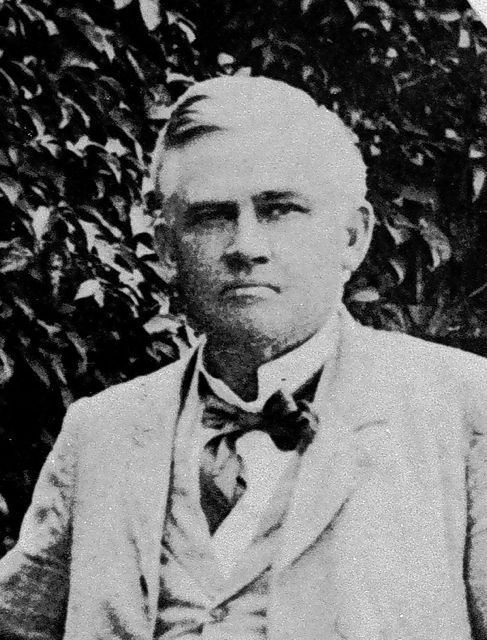

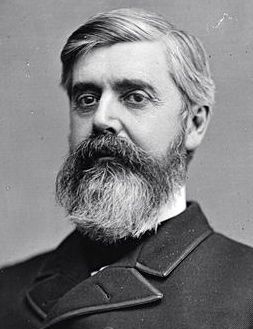

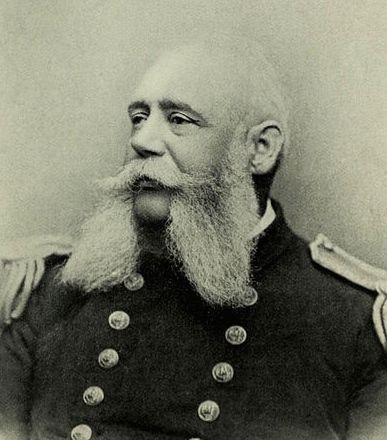

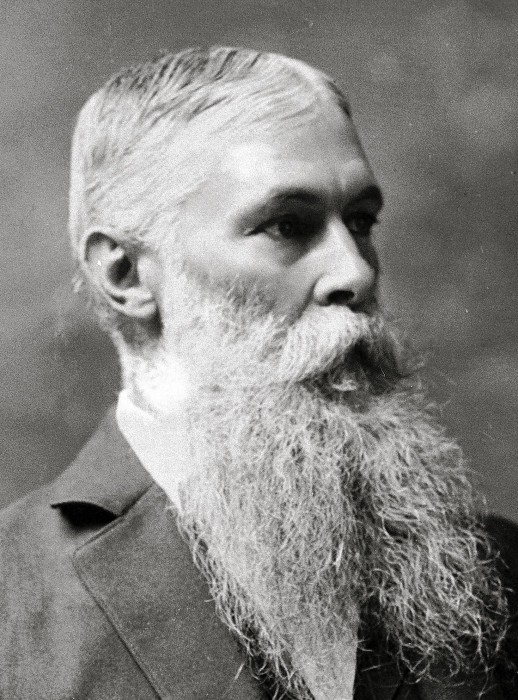

at the request of Queen Lili‘uokalani, Hawaiian Head of State, in March 1893. At the center of the investigation were the actions taken by U.S. Minister Plenipotentiary John Stevens  and the commander of U.S. troops aboard the U.S.S. Boston anchored in Honolulu Harbor, Captain Gilbert Wiltse. The intervention occurred during President Benjamin Harrison’s administration. The President appointed James Blount as Special Commissioner who submitted reports between April and July 1893 to U.S. Secretary of State Walter Gresham. The investigation was concluded by Gresham on October 18, 1893. President Cleveland notified the Congress of the conclusion of the investigation by presidential message on December 18, 1893, while negotiations were still taking place with the Queen in Honolulu.

and the commander of U.S. troops aboard the U.S.S. Boston anchored in Honolulu Harbor, Captain Gilbert Wiltse. The intervention occurred during President Benjamin Harrison’s administration. The President appointed James Blount as Special Commissioner who submitted reports between April and July 1893 to U.S. Secretary of State Walter Gresham. The investigation was concluded by Gresham on October 18, 1893. President Cleveland notified the Congress of the conclusion of the investigation by presidential message on December 18, 1893, while negotiations were still taking place with the Queen in Honolulu.

The investigation determined that the United States unlawfully intervened in the internal affairs of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and that its diplomat and troops were directly responsible for the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian government. Gresham recommended to President Cleveland that the Hawaiian government must be restored and compensation must be provided. This prompted executive mediation between President Cleveland and Queen Lili‘uokalani to settle the dispute and by exchange of notes an executive agreement, called the “Agreement of Restoration,” was concluded whereby the President committed to the restoration of the Hawaiian government and the Queen, thereafter, to grant amnesty to the insurgents. The President did not carry out the international agreement because of political wrangling in the Congress, and President Cleveland’s successor, William McKinley, unilaterally seized the Hawaiian Islands during the Spanish-American War on August 12, 1898. Hawai‘i has been under an illegal and prolonged occupation ever since.

Here follows Gresham’s report to President Cleveland regarding U.S. intervention in Hawai‘i that took place under President Benjamin Harrison’s administration.

Here follows Gresham’s report to President Cleveland regarding U.S. intervention in Hawai‘i that took place under President Benjamin Harrison’s administration.

Department of State,

Washington, October 18, 1893

The President:

The full and impartial reports submitted by the Hon. James H. Blount, your special commissioner to the Hawaiian Islands, established the following facts:

Queen Liliuokalani announced her intention on Saturday, January 14, 1893, to proclaim a new constitution, but the opposition of her ministers and other induced her to speedily change her purpose and make public announcement of that fact.

At a meeting in Honolulu, late on the afternoon of that day, a so-called committee of public safety, consisting of thirteen men, being all or nearly all who were present, was appointed “to consider the situation and devise ways and means for the maintenance of the public peace and the protection of life and property,” and at a meeting of this committee on the 15th, or the forenoon of the 16th of January, it was resolved amongst other things that a provisional government be created “to exist until terms of union with the United States of America have been negotiated and agreed upon.” At a mass meeting which assembled at 2 p.m. on the last named day, the Queen and her supporters were condemned and denounced, and the committee was continued and all its act approved.

Later the same afternoon the committee addressed a letter to John L. Stevens, the American minister at Honolulu, stating that the lives and property of the people were in peril and appealing to him and the United States forces at his command for assistance. This communication concluded “we are unable to protect ourselves without aid, and therefore hope for the protection of the United States forces.” On receipt of this letter Mr. Stevens requested

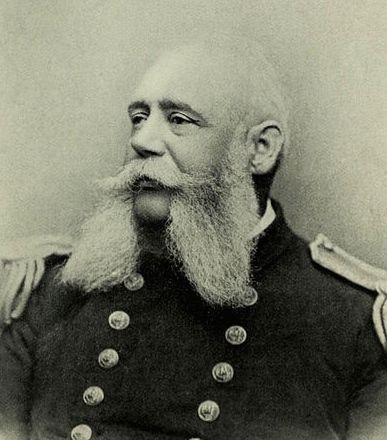

American minister at Honolulu, stating that the lives and property of the people were in peril and appealing to him and the United States forces at his command for assistance. This communication concluded “we are unable to protect ourselves without aid, and therefore hope for the protection of the United States forces.” On receipt of this letter Mr. Stevens requested  Capt. Wiltse, commander of the U.S.S. Boston, to land a force “for the protection of the United States legation, United States consulate, and to secure the safety of American life and property.” The well armed troops, accompanied by two gatling guns, were promptly landed and marched through the quiet streets of Honolulu to a public hall, previously secured by Mr. Stevens for their accommodation. This hall was just across the street form the government building, and in plain view of the Queen’s palace. The reason for thus locating the military will presently appear. The governor of the Island immediately addressed to Mr. Stevens a communication protesting against the act as an unwarranted invasion of Hawaiian soil and reminding him that the proper authorities had never denied permission to the naval forces of the United States to land for drill or any other proper purpose.

Capt. Wiltse, commander of the U.S.S. Boston, to land a force “for the protection of the United States legation, United States consulate, and to secure the safety of American life and property.” The well armed troops, accompanied by two gatling guns, were promptly landed and marched through the quiet streets of Honolulu to a public hall, previously secured by Mr. Stevens for their accommodation. This hall was just across the street form the government building, and in plain view of the Queen’s palace. The reason for thus locating the military will presently appear. The governor of the Island immediately addressed to Mr. Stevens a communication protesting against the act as an unwarranted invasion of Hawaiian soil and reminding him that the proper authorities had never denied permission to the naval forces of the United States to land for drill or any other proper purpose.

About the same time the Queen’s minister of foreign affairs sent a note to Mr. Stevens asking why the troops had been landed and informing him that the proper authorities were able and willing to afford full protection to the American legation and all American interests in Honolulu. Only evasive replies were sent to these communications.

While there were no manifestations of excitement or alarm in the city, and the people were ignorant of the contemplated movements, the committee entered the Government building, after first ascertaining that it was unguarded, and read a proclamation declaring that the existing Government was overthrown and a Provisional Government established in its place, “to exist until terms of union with the United States of America have been negotiated and agreed upon.” No audience was present when the proclamation was read, but during the reading 40 to 50 men, some of them indifferently armed, entered the room. The executive and advisory councils mentioned in the proclamation at once addressed a communication to Mr. Stevens, informing him that the monarchy had been abrogated and a provisional government established. This communication concluded:

Such Provisional Government has been proclaimed, is now in possession of the Government departmental buildings, the archives, and the treasury, and is in control of the city. We hereby request that you will, on behalf of the United States, recognize it as the existing de facto Government of the Hawaiian Islands and afford to it the moral support of your Government, and, if necessary, the support of American troops to assist in preserving the public peace.

On receipt of this communication, Mr. Stevens immediately recognized the new Government, and, in a letter addressed to Sanford B. Dole, its President, informed him that he had done so. Mr. Dole replied:

On receipt of this communication, Mr. Stevens immediately recognized the new Government, and, in a letter addressed to Sanford B. Dole, its President, informed him that he had done so. Mr. Dole replied:

Government Building,

Honolulu, January 17, 1893

Sir: I acknowledge receipt of your valued communication of this day, recognizing the Hawaiian Provisional Government, and express deep appreciation of the same.

We have conferred with the ministers of the late Government, and have made demand upon the marshal to surrender the station house. We are not actually yet in possession of the station house, but as night is approaching and our forces may be insufficient to maintain order, we request the immediate support of the United States forces, and would request that the commander of the United States forces take command of our military forces, so that they may act together for the protection of the city.

Respectfully, yours,

Sanford B. Dole,

Chaiman Executive Council.

His Excellency John L. Stevens,

United States Minister Resident.

Note of Mr. Stevens at the end of the above communication.

“The above request not complied with.”

Stevens.

The station house was occupied by a well armed force, under the command of a resolute capable, officer. The same afternoon the Queen, her ministers, representatives of the Provisional Government, and other held a conference at the palace. Refusing to recognize the new authority or surrender to it, she was informed that the Provisional Government had the support of the American minister, and, if necessary, would be maintained by the military force of the United States then present; that any demonstration on her part would precipitate a conflict with that force; that she could not, with hope of success, engage in war with the United States, and that resistance would result in a useless sacrifice of life. Mr. Damon, one of the chief leader of the movement, and afterwards vice-president of the Provisional Government, informed the Queen that she could surrender under protest and her case would be considered later at Washington. Believing that, under the circumstances, submission was a duty, and that her case would be fairly considered by the President of the United States, the Queen finally yielded and sent to the Provisional Government the paper, which reads:

“I, Lili‘uokalani, by the grace of God and under the constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Queen, do hereby solemnly protest against any and all acts done against myself and the constitutional Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom by certain persons claiming to have established a provisional government of and for this Kingdom.

That I yield to the superior force of the United States of America whose Minister Plenipotentiary, His Excellency John L. Stevens, has caused United States troops to be landed at Honolulu and declared that he would support the provisional government.

Now to avoid any collision of armed forces, and perhaps the loss of life, I do this under protest and impelled by said force yield my authority until such time as the Government of the United States shall, upon facts being presented to it, undo the action of its representatives and reinstate me in the authority which I claim as the Constitutional Sovereign of the Hawaiian Islands.”

When this paper was prepared at the conclusion of the conference, and signed by the Queen and her ministers, a number of persons, including one or more representatives of the Provisional Government, who were still present and understood its contents, by their silence, at least, acquiesced in its statements, and, when it was carried to President Dole, he indorsed upon it, “Received from the hands of the late cabinet this 17th day of January, 1893,” without challenging the truth of any of its assertions. Indeed, it was not claimed on the 17th day of January, or for some time thereafter, by any of the designated officers of the Provisional Government or any annexationist that the Queen surrendered otherwise than as stated in her protest.

In his dispatch to Mr. Foster of January 18, describing the so-called revolution, Mr. Stevens says:

The committee of public safety forthwith took possession of the Government building, archives, and treasury, and installed the Provisional Government at the head of the respective departments. This being an accomplished fact, I promptly recognized the Provisional Government as the de facto government of the Hawaiian Islands.

In Secretary Foster’s communication of February 15 to the President, laying before him the treaty of annexation, with the view to obtaining the advice and consent of the Senate thereto, he says:

At the time the Provisional Government took possession of the Government building no troops or officers of the United States were present or took any part whatever in the proceedings. No public recognition was accorded to the Provisional Government by the United States minister until after the Queen’s abdication, and when they were in effective possession of the Government building, the archives, the treasury, the barracks, the police station, and all the potential machinery of the Government.

Similar language is found in an official letter addressed to Secretary Foster on February 3 by the special commissioners sent to Washington by the Provisional Government to negotiate a treaty of annexation.

These statements are utterly at variance with the evidence, documentary and oral, contained in Mr. Blount’s reports. They are contradicted by declarations and letters of President Dole and other annexationists and by Mr. Stevens’s own verbal admissions to Mr. Blount. The Provisional Government was recognized when it had little other than a paper existence, and when the legitimate government was in full possession and control of the palace, the barracks, and the police station. Mr. Stevens’s well known hostility and the threatening presence of the force landed from the Boston was all that could then have excited serious apprehension in the minds of the Queen, her officers, and loyal supporters.

It is fair to say that Secretary Foster’s statements were based upon information which he had received from Mr. Stevens and the special commissioners, but I am unable to see that they were deceived. The troops were landed, not to protect American life and property, but to aid in overthrowing the existing government. Their very presence implied coercive measures against it.

In a statement given to Mr. Blount, by Admiral Skerret, the ranking naval officer at Honolulu, he says:

“If the troops were landed simply to protect American citizens and interests, they were badly stationed in Arion Hall, but if the intention was to aid the Provisional Government they were wisely stationed.”

This hall was so situated that the troops in it easily commanded the Government building, and the proclamation was real under the protection of American guns. At an early stage of the movement, if not at the beginning, Mr. Stevens promised the annexationists that as soon as they obtained possession of the Government building and there read a proclamation of the character above referred to, he would at once recognize them as a de facto government, and support them by landing a force from our war ship then in the harbor, and he kept that promise. This assurance was the inspiration on the movement, and without it the annexationists would not have exposed themselves to the consequences of failure. They relied upon no military force of their own, for they had none worthy of the name. The Provisional Government was established by the action of the American minister and the presence of the troops landed from the Boston, and its continued existence is due to the belief of the Hawaiians that if they made an effort to overthrow it, they would encounter the armed forces of the United States.

The earnest appeals to the American minister for military protection by the officers of that Government, after it had been recognized, show the utter absurdity of the claim that it was established by a successful revolution of the people of the Islands. Those appeals were a confession by the men who made them of their weakness and timidity. Courageous men, conscious of their strength and the justice of their cause, do not thus act. It is not now claimed that a majority of the people, having the right to vote under the constitution of 1887, ever favored the existing authority or annexation to this or any other country. They earnestly desire that the government of their choice shall be restored and its independence respected.

Mr. Blount states that while at Honolulu he did not meet a single annexationist who expressed willingness to submit the question to a vote of the people, nor did he talk with one on that subject who did not insist that if the Islands were annexed suffrage should be so restricted as to give complete control to foreigners or whites. Representative annexationists have repeatedly made similar statements to the undersigned.

The Government of Hawaii surrendered its authority under a threat of war, until such time only as the Government of the United States, upon the facts being presented to it, should reinstate the constitutional sovereign, and the Provisional Government was created “to exist until terms of union with the United States of America have been negotiated and agreed upon.” A careful consideration of the fact will, I think, convince you that the treaty which was withdrawn from the Senate for further consideration should not be resubmitted for its action thereon.

Should not the great wrong done to a feeble but independent State by an abuse of the authority of the United States be undone by restoring the legitimate government? Anything short of that will not, I respectfully submit, satisfy the demands of justice.

Can the United States consistently insist that other nations shall respect the independence of Hawaii while not respecting it themselves? Our Government was the first to recognize the independence of the Islands and it should be the last to acquire sovereignty over them by force and fraud.

Respectfully submitted.

W.Q. Gresham.

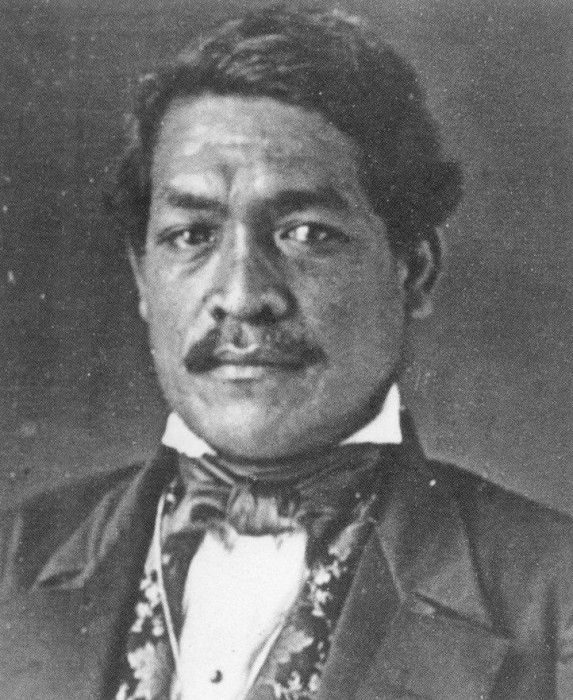

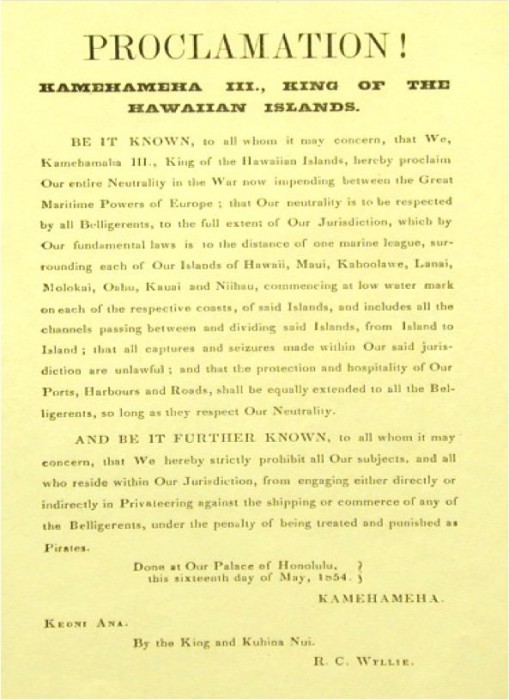

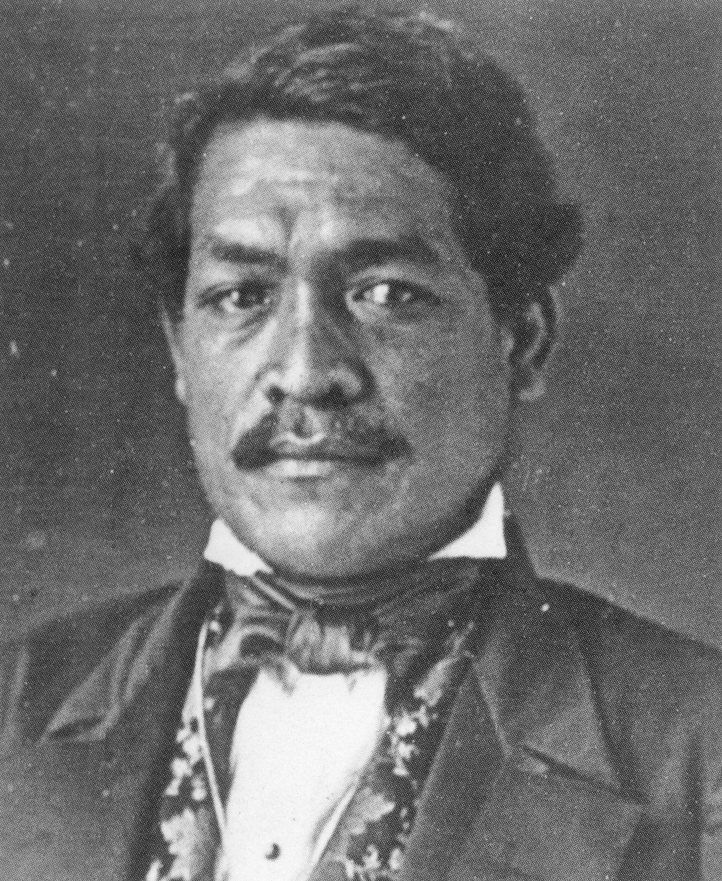

In the summer of 1842, Kamehameha III moved forward to secure the position of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a recognized independent state under international law. He sought the formal recognition of Hawaiian independence from the three naval powers of the world at the time—Great Britain, France, and the United States. To accomplish this, Kamehameha III commissioned three envoys, Timoteo Ha‘alilio, William Richards, who at the time was still an American Citizen, and Sir George Simpson, a British subject. Of all three powers, it was the British that had a legal claim over the Hawaiian Islands through cession by Kamehameha I, but for political reasons the British could not openly exert its claim over the other two naval powers. Due to the islands prime economic and strategic location in the middle of the north Pacific, the political interest of all three powers was to ensure that none would have a greater interest than the other. This caused Kamehameha III “considerable embarrassment in managing his foreign relations, and…awakened the very strong desire that his Kingdom shall be formally acknowledged by the civilized nations of the world as a sovereign and independent State.”

In the summer of 1842, Kamehameha III moved forward to secure the position of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a recognized independent state under international law. He sought the formal recognition of Hawaiian independence from the three naval powers of the world at the time—Great Britain, France, and the United States. To accomplish this, Kamehameha III commissioned three envoys, Timoteo Ha‘alilio, William Richards, who at the time was still an American Citizen, and Sir George Simpson, a British subject. Of all three powers, it was the British that had a legal claim over the Hawaiian Islands through cession by Kamehameha I, but for political reasons the British could not openly exert its claim over the other two naval powers. Due to the islands prime economic and strategic location in the middle of the north Pacific, the political interest of all three powers was to ensure that none would have a greater interest than the other. This caused Kamehameha III “considerable embarrassment in managing his foreign relations, and…awakened the very strong desire that his Kingdom shall be formally acknowledged by the civilized nations of the world as a sovereign and independent State.” While the envoys were on their diplomatic mission, a British Naval ship, HBMS Carysfort, under the command of Lord Paulet, entered Honolulu harbor on February 10, 1843, making outrageous demands on the Hawaiian government. Basing his actions on complaints made to him in letters from the British Consul, Richard Charlton, who was absent from the kingdom at the time, Paulet eventually seized control of the Hawaiian government on February 25, 1843, after threatening to level Honolulu with cannon fire. Kamehameha III was forced to surrender the kingdom, but did so under written protest and pending the outcome of the mission of his diplomats in Europe. News

While the envoys were on their diplomatic mission, a British Naval ship, HBMS Carysfort, under the command of Lord Paulet, entered Honolulu harbor on February 10, 1843, making outrageous demands on the Hawaiian government. Basing his actions on complaints made to him in letters from the British Consul, Richard Charlton, who was absent from the kingdom at the time, Paulet eventually seized control of the Hawaiian government on February 25, 1843, after threatening to level Honolulu with cannon fire. Kamehameha III was forced to surrender the kingdom, but did so under written protest and pending the outcome of the mission of his diplomats in Europe. News  of Paulet’s action reached Admiral Richard Thomas of the British Admiralty, and he sailed from the Chilean port of Valparaiso and arrived in the islands on July 25, 1843. After a meeting with Kamehameha III, Admiral Thomas determined that Charlton’s complaints did not warrant a British takeover and ordered the restoration of the Hawaiian government, which took place in a grand ceremony on July 31, 1843. At a thanksgiving service after the ceremony, Kamehameha III proclaimed before a large crowd, ua mau ke ea o ka ‘aina i ka pono (the life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness). The King’s statement became the national motto.

of Paulet’s action reached Admiral Richard Thomas of the British Admiralty, and he sailed from the Chilean port of Valparaiso and arrived in the islands on July 25, 1843. After a meeting with Kamehameha III, Admiral Thomas determined that Charlton’s complaints did not warrant a British takeover and ordered the restoration of the Hawaiian government, which took place in a grand ceremony on July 31, 1843. At a thanksgiving service after the ceremony, Kamehameha III proclaimed before a large crowd, ua mau ke ea o ka ‘aina i ka pono (the life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness). The King’s statement became the national motto.