There is a fundamental question regarding the American occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom that rests on two positions. The first proposition is that the American occupation began on January 17, 1893 at the time of the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian “government” and ended when American troops were ordered to vacate Hawaiian territory on April 1, 1893 by Presidential investigator James Blount. And that a second American occupation began on August 12, 1898 during the Spanish American War which has lasted to date. The second proposition is that the American occupation began on January 17, 1893 and has remained a belligerent occupation ever since.

What is fundamental and crucial in precisely determining this question of occupation is that occupation triggers the law of occupation, which follows an invasion. When occupation comes to an end so do the laws occupation. This is separate and distinct from the laws and customs of war triggered by an invasion, and the law of occupation that mandates the occupier to provisionally administer the laws of the occupied State under Section III (Articles 42-56) of the 1899 Hague Convention, II, which was later superseded by Section III (Articles 42-56) of the 1907 Hague Convention, IV, and the 1949 Geneva Convention, IV.

At the center of occupation is “effectiveness.” In other words, territory is only occupied when it comes under the effective control of a foreign state’s military. For without effectiveness, the occupier would not be able to carry out the duties and obligations of an occupier under international law in the administration of the laws of the occupied State.

Although an invasion of territory would trigger the laws and customs of war on land, it does not simultaneously trigger the laws of occupation, because the invasion may be transient and ongoing. But when the invader becomes fixed and establishes its authority it triggers the laws of occupation. Article 42 of the 1899 Hague Convention, II, which was considered customary international law at the time, states that, “Territory is considered occupied when it is actually place under the authority of the hostile army. The occupation applies only to the territory where such authority is established, and in a position to assert itself.” Article 42 of the 1907 Hague Convention, IV, is relatively the same except for minor changes in wording.

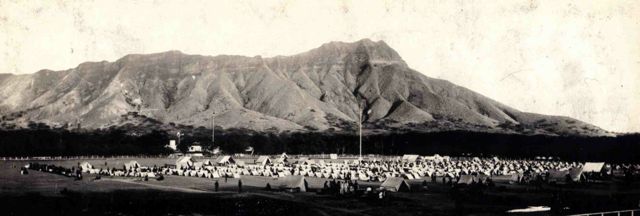

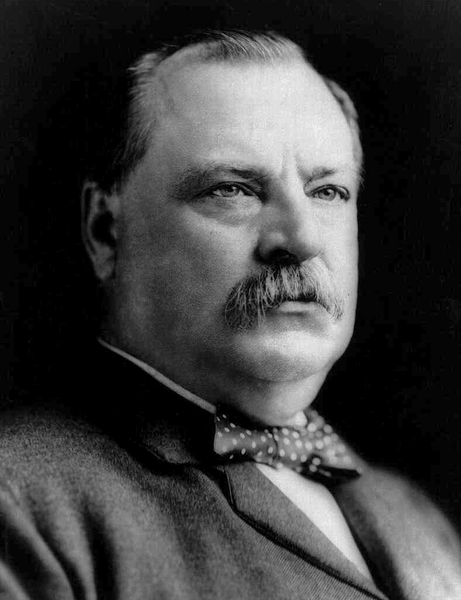

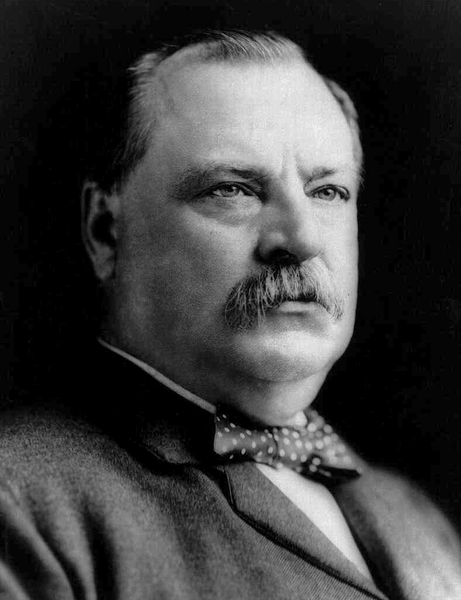

At first glance, Article 42 refers to the presence of a “hostile army.” So if we were to look at the U.S. troops that were present in Honolulu on January 17, 1893, we need to determine at what point were they in a position of established authority. In his message of December 18, 1893, President Cleveland apprised the Congress that when U.S. troops landed in Honolulu on Monday January 16 it was an invasion. Cleveland stated, “The men, upwards of 160 in all, were supplied with double cartridge belts filled with ammunition and with haversacks and canteens, and were accompanied by a hospital corps with stretchers and medical supplies. This military demonstration upon the soil of Honolulu was of itself an act of war.” Cleveland further states that, “the military occupation of Honolulu by the United States on the day mentioned was wholly without justification, either as an occupation by consent or as an occupation necessitated by dangers threatening American life and property.”

The question, however, from a strictly legal standpoint, did the U.S. troops establish its authority under the law of occupation, and, if so, to what extent did this authority extend regarding territorial control. The troops were occupying a very small defensive position between two buildings—Music Hall and Arian Hall, on Mililani Street. Cleveland explained to the Congress,

“The United States forces being now on the scene and favorably stationed, the committee proceeded to carry out their original scheme. They met the next morning, Tuesday, the 17th, perfected the plan of temporary government, and fixed upon its principal officers, ten of whom were drawn from the thirteen members of the Committee of Safety. Between one and two o’clock, by squads and by different routes to avoid notice, and having first taken the precaution of ascertaining whether there was any one there to oppose them, they proceeded to the Government building almost entirely without auditors. It is said that before the reading was finished quite a concourse of persons, variously estimated at from 50 to 100, some armed and some unarmed, gathered about the committee to give them aid and confidence. This statement is not important, since the one controlling factor in the whole affair was unquestionably the United States marines, who, drawn up under arms and with artillery in readiness only seventy-six yards distant, dominated the situation.”

“The United States forces being now on the scene and favorably stationed, the committee proceeded to carry out their original scheme. They met the next morning, Tuesday, the 17th, perfected the plan of temporary government, and fixed upon its principal officers, ten of whom were drawn from the thirteen members of the Committee of Safety. Between one and two o’clock, by squads and by different routes to avoid notice, and having first taken the precaution of ascertaining whether there was any one there to oppose them, they proceeded to the Government building almost entirely without auditors. It is said that before the reading was finished quite a concourse of persons, variously estimated at from 50 to 100, some armed and some unarmed, gathered about the committee to give them aid and confidence. This statement is not important, since the one controlling factor in the whole affair was unquestionably the United States marines, who, drawn up under arms and with artillery in readiness only seventy-six yards distant, dominated the situation.”

Cleveland was not explaining an occupation that would invoke the law of occupation, but rather an invasion and regime change. But on February 1, 1893, the United States diplomat, John Stevens, declared the Hawaiian Islands to be an American protectorate. So from a position of international law it would be February 1 that would trigger the duty and obligations of the law of occupation because it would appear that this date is where the United States gained effective control of foreign territory and established its authority over it.

However, if you add to the mix the so-called Provisional Government it presents a very different picture. First, the President told Congress that the provisional government was neither a de jure government, which is the lawful government, nor a de facto government, which by definition under international law is a successful revolution. A de facto government has to be in effective control of all the governmental machinery of the government it is revolting against, before it can be considered de facto, because when it is not it is still in a state of revolt and the treason statute would apply. This is why the United States of America was not considered a de facto government until after King George III signed the Treaty of Paris on September 3, 1783, that ended the seven year revolt. When the British colonies declared their independence on July 4, 1776 they became insurgents who committed treason to the British government.

Cleveland addressed this requirement of international law when he stated to the Congress, “That it was not in such possession of the Government property and agencies as entitled it to recognition is conclusively proved by a note found in the files of the Legation at Honolulu, addressed by the declared head of the provisional government to Minister Stevens, dated January 17, 1893, in which he acknowledges with expressions of appreciation the Minister’s recognition of the provisional government, and states that it is not yet in the possession of the station house (the place where a large number of the Queen’s troops were quartered), though the same had been demanded of the Queen’s officers in charge. Nevertheless, this wrongful recognition by our Minister placed the Government of the Queen in a position of most perilous perplexity. On the one hand she had possession of the palace, of the barracks, and of the police station, and had at her command at least five hundred fully armed men and several pieces of artillery. Indeed, the whole military force of her kingdom was on her side and at her disposal, while the Committee of Safety, by actual search, had discovered that there were but very few arms in Honolulu that were not in the service of the Government. In this state of things if the Queen could have dealt with the insurgents alone her course would have been plain and the result unmistakable. But the United States had allied itself with her enemies, had recognized them as the true Government of Hawaii, and had put her and her adherents in the position of opposition against lawful authority.”

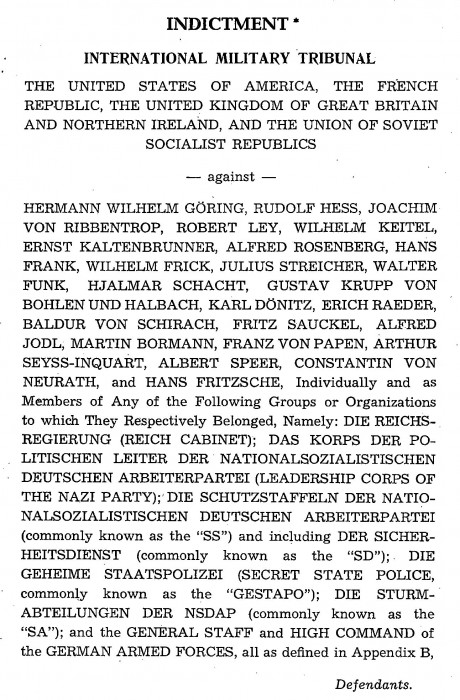

The insurgents seized control of the de jure Government of the Queen under the protection of U.S. troops, and thereafter compelled everyone in Government to sign oaths of allegiance. By unlawfully seizing the reigns of government in violation of international law, it does not transform itself into a de jure government. It is a state of emergency born out of a violation of international law. Therefore, if the so-called Provisional Government was not a government at all, but rather enemies of the State who committed high treason under Hawaiian law, then what would it be classified as for the purposes of international law since the United States was its creator. Yes it could be called a puppet of the United States, but this does not mean anything under international law and the law of occupation.

Under international law, the Provisional Government would be classified as an American “militia” illegally established on Hawaiian territory by the United States. Article 1 of the 1899 Hague Convention, II, states, “The laws, rights, and duties of war apply not only to armies, but also to militia and volunteer corps fulfilling the following conditions: 1. To be commanded by a person responsible for his subordinates; 2. To have a fixed distinctive emblem recognizable at a distance; 3. To carry arms openly; and 4. To conduct their operations in accordance with the laws and customs of war.” This Article remained unchanged in the 1907 Hague Convention, IV.

There can be no doubt that the American militia called the Provisional Government began to be in effective control as a result of U.S. intervention, but this effectiveness did not reach its peak on January 17. It was a gradual escalation of effectiveness that began to grow from the city of Honolulu to the outlying government offices on the outer islands. But when the U.S. diplomat established protectorate status on February 1, this could be definitive as to when the law of occupation was triggered. Up to this point it was an invasion and not an occupation for the purposes of international law. Although U.S. troops departed Hawaiian territory on April 1, 1893, the American militia maintained itself through the hiring of mercenaries from the United States.

On July 4, 1894, the American militia changed its name to the Republic of Hawai‘i and continued to have government officers and employees sign oaths of allegiance under threat of American mercenaries who continued to be employed by the insurgency. The proclamation of the insurgents stated, “it is hereby declared, enacted and proclaimed by the Executive and Advisory Councils of the Provisional Government and by the elected Delegates, constituting said Constitutional Convention, that on and after the Fourth day of July, A.D. 1894, the said Constitution shall be the Constitution of the Republic of Hawaii and the Supreme Law of the Hawaiian Islands.”

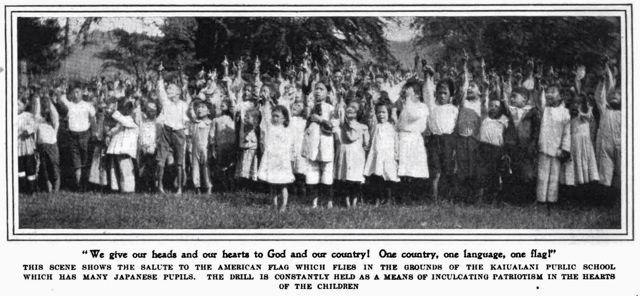

On April 30, 1900, the U.S. Congress by statute changed the name of the American militia called the Republic of Hawai‘i to the Territory of Hawai‘i. The Territorial Act provided, that “the laws of [the Republic of Hawai‘i] not inconsistent with the Constitution or laws of the United States or the provisions of this Act shall continue in force,” and that “all persons who were citizens of the Republic of Hawaii on August twelfth, eighteen hundred and ninety-eight, are hereby declared to be citizens of the United States and citizens of the Territory of Hawai‘i.”

On March 18, 1959, the U.S. Congress again by statute changed the name of the American militia called the Territory of Hawai‘i to the State of Hawai‘i. The Statehood Act provided that all “Territorial laws in force in the Territory of Hawaii at the time of its admission into the Union shall continue in force in the State of Hawaii, except as modified or changed by this Act or by the constitution of the State, and shall be subject to repeal or amendment by the Legislature of the State of Hawaii.” The State of Hawai‘i today is an American militia and not a government.

Therefore, when we add the American militia that was formerly called the Provisional Government, the Republic of Hawai‘i, the Territory of Hawai‘i and now the State of Hawai‘i, into the equation and not just the physical presence and effective control of U.S. troops whether in 1893 or 1898, international law would recognize the beginning of the belligerent occupation to be February 1, 1893, which continues to date. The American occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom is the longest ever in the history of international relations that emerged since the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648.

From September 10-12, 2015, fifteen academic scholars from around the world who were political scientists and historians came together to present papers on non-European powers at a conference/workshop held at the University of Cambridge, United Kingdom. Attendees of the conference were by invitation only and the papers presented at the conference are planned to be published in a volume with Oxford University Press.

From September 10-12, 2015, fifteen academic scholars from around the world who were political scientists and historians came together to present papers on non-European powers at a conference/workshop held at the University of Cambridge, United Kingdom. Attendees of the conference were by invitation only and the papers presented at the conference are planned to be published in a volume with Oxford University Press.

While King Kalakaua was visiting Japan in 1881, Emperor Meiji “asked for Hawai‘i to grant full recognition to Japan and thereby create a precedent for the Western powers to follow.” Kalakaua was unable to grant the Emperor’s request, but it was done by his successor Queen Lili‘uokalani. Hawaiian recognition of Japan’s full sovereignty and repeal of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s consular jurisdiction in Japan provided in the Hawaiian-Japanese Treaty of 1871, would take place in 1893 by

While King Kalakaua was visiting Japan in 1881, Emperor Meiji “asked for Hawai‘i to grant full recognition to Japan and thereby create a precedent for the Western powers to follow.” Kalakaua was unable to grant the Emperor’s request, but it was done by his successor Queen Lili‘uokalani. Hawaiian recognition of Japan’s full sovereignty and repeal of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s consular jurisdiction in Japan provided in the Hawaiian-Japanese Treaty of 1871, would take place in 1893 by  By direction of Her Majesty Queen Lili‘uokalani, R.W. Irwin, Hawaiian Minister to the Court of Japan in Tokyo sent a diplomatic note to Mutsu Munemitsu, Japanese Minister of Foreign Affairs on January 18, 1893 announcing the Hawaiian Kingdom’s abandonment of consular jurisdiction. Irwin stated:

By direction of Her Majesty Queen Lili‘uokalani, R.W. Irwin, Hawaiian Minister to the Court of Japan in Tokyo sent a diplomatic note to Mutsu Munemitsu, Japanese Minister of Foreign Affairs on January 18, 1893 announcing the Hawaiian Kingdom’s abandonment of consular jurisdiction. Irwin stated:

“The United States forces being now on the scene and favorably stationed, the committee proceeded to carry out their original scheme. They met the next morning, Tuesday, the 17th, perfected the plan of temporary government, and fixed upon its principal officers, ten of whom were drawn from the thirteen members of the Committee of Safety. Between one and two o’clock, by squads and by different routes to avoid notice, and having first taken the precaution of ascertaining whether there was any one there to oppose them, they proceeded to the Government building almost entirely without auditors. It is said that before the reading was finished quite a concourse of persons, variously estimated at from 50 to 100, some armed and some unarmed, gathered about the committee to give them aid and confidence. This statement is not important, since the one controlling factor in the whole affair was unquestionably the United States marines, who, drawn up under arms and with artillery in readiness only seventy-six yards distant, dominated the situation.”

“The United States forces being now on the scene and favorably stationed, the committee proceeded to carry out their original scheme. They met the next morning, Tuesday, the 17th, perfected the plan of temporary government, and fixed upon its principal officers, ten of whom were drawn from the thirteen members of the Committee of Safety. Between one and two o’clock, by squads and by different routes to avoid notice, and having first taken the precaution of ascertaining whether there was any one there to oppose them, they proceeded to the Government building almost entirely without auditors. It is said that before the reading was finished quite a concourse of persons, variously estimated at from 50 to 100, some armed and some unarmed, gathered about the committee to give them aid and confidence. This statement is not important, since the one controlling factor in the whole affair was unquestionably the United States marines, who, drawn up under arms and with artillery in readiness only seventy-six yards distant, dominated the situation.”

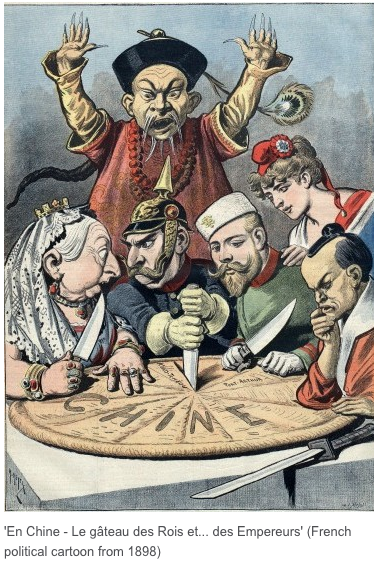

“In the heyday of empire, most of the world was ruled, directly or indirectly, by the European powers. On the eve of the First World War, only a few non-European states had maintained their formal sovereignty: Abyssinia (Ethiopia), China, Japan, the Ottoman Empire, Persia (Iran), and Siam (Thailand). Some others kept their independence for a while, but then succumbed to imperial powers, such as Hawaii, Korea, Madagascar, and Morocco. Facing imperialist incursion, the political elites of these countries sought to overcome their political vulnerability by engaging with the European powers and seeking recognition as equals.

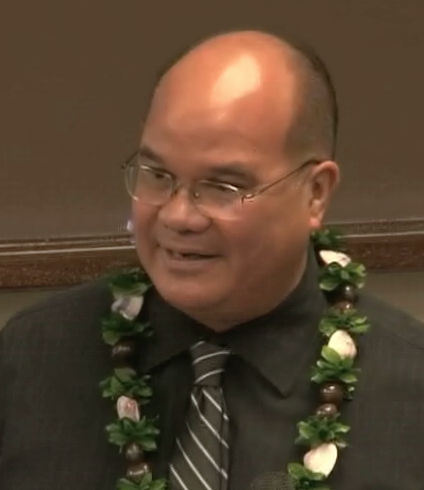

“In the heyday of empire, most of the world was ruled, directly or indirectly, by the European powers. On the eve of the First World War, only a few non-European states had maintained their formal sovereignty: Abyssinia (Ethiopia), China, Japan, the Ottoman Empire, Persia (Iran), and Siam (Thailand). Some others kept their independence for a while, but then succumbed to imperial powers, such as Hawaii, Korea, Madagascar, and Morocco. Facing imperialist incursion, the political elites of these countries sought to overcome their political vulnerability by engaging with the European powers and seeking recognition as equals. Dr. David Keanu Sai was 1 of 15 scholars from across the world that was invited to present their research and expertise that centers on non-European States. Dr. Sai’s research focuses on the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent and sovereign state and its continuity to date under an illegal and prolonged occupation by the United States of America since the Spanish-American War. He will be presenting a paper titled “Hawaiian Neutrality: From the Crimean Conflict to the Spanish-American War.” The following is Dr. Sai’s abstract for his paper:

Dr. David Keanu Sai was 1 of 15 scholars from across the world that was invited to present their research and expertise that centers on non-European States. Dr. Sai’s research focuses on the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent and sovereign state and its continuity to date under an illegal and prolonged occupation by the United States of America since the Spanish-American War. He will be presenting a paper titled “Hawaiian Neutrality: From the Crimean Conflict to the Spanish-American War.” The following is Dr. Sai’s abstract for his paper:

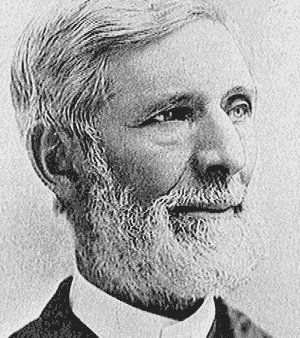

On November 20, 1892, U.S. Diplomat John Stevens assigned to Hawai‘i stated in a confidential

On November 20, 1892, U.S. Diplomat John Stevens assigned to Hawai‘i stated in a confidential

The

The