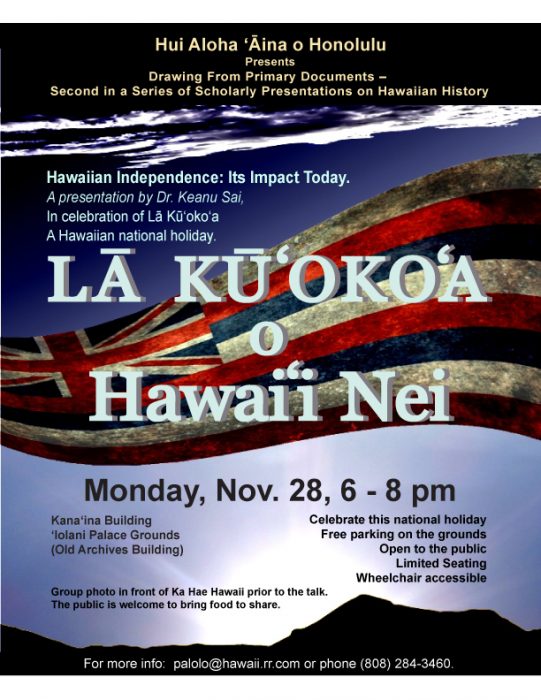

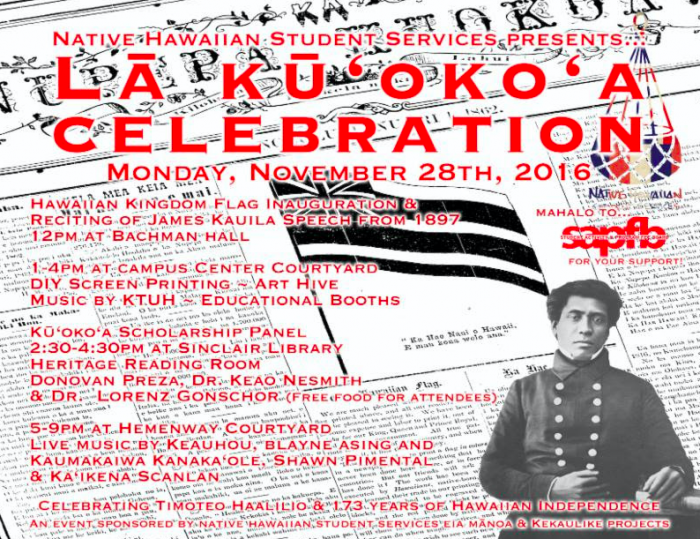

Celebrating Hawaiian Independence: Dr. Keanu Sai to Present on the Palace Grounds

13

https://vimeo.com/192878178

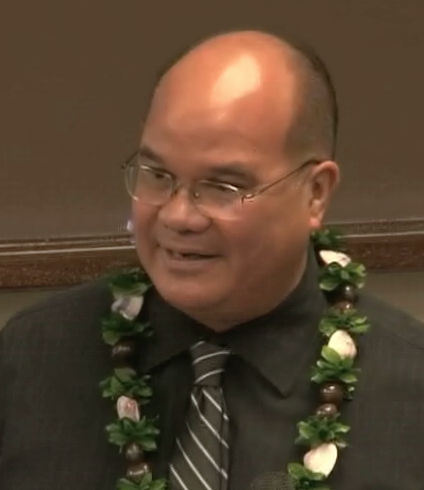

Dr. Lynette Cruz, host of “Issues that Matter,” interviews Dr. Keanu Sai on recent trip to Italy. Dr. Sai was invited to participate in an academic conference in Ravenna, Italy, as well as guest lectures as the University of Siena Law School and at the University of Torino.

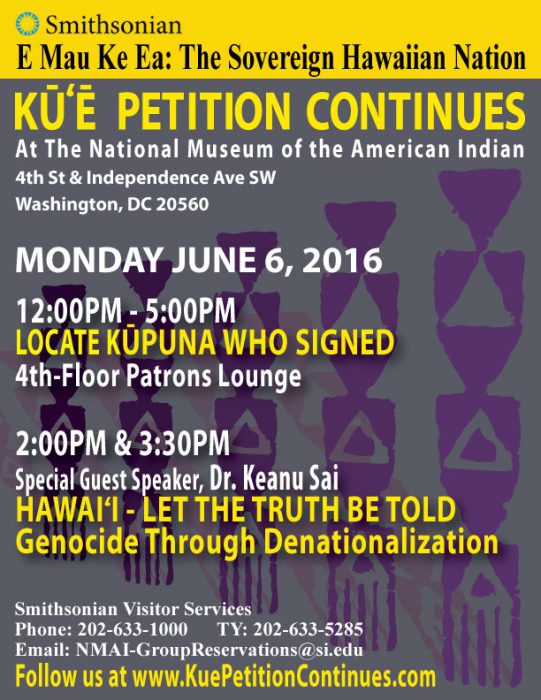

The Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center (APA) invited Dr. Keanu Sai, along with over forty artists and scholars, to participate in its initiative “A Cultural Lab on Imagined Futures.” APA’s initiative is a unique way to experience a museum. As an agency of the Smithsonian Institute, APA is “a migratory museum that brings Asian Pacific American history, art and culture to you through innovative museum experiences online and throughout the United States.” The traveling museums are called “Culture Labs.”

Imagined Futures will be held on Veterans Day weekend (November 12-13, 2016) at 477 Broadway, SOHO/Chinatown, New York City, from 11 am – 9 pm.

Dr. Sai’s exhibit is the American occupation of Hawai‘i seen through the lens of the science fiction movie “The Matrix.” The science fiction thriller “depicts a dystopian future in which reality as perceived by most humans is actually a simulated reality called ‘the Matrix,’ created by sentient machines to subdue the human population, while their bodies’ heat and electrical activity are used as an energy source. Computer programmer ‘Neo’ learns this truth and is drawn into a rebellion against the machines, which involves other people who have been freed from the ‘dream world.’”

Dr. Sai’s exhibit is the American occupation of Hawai‘i seen through the lens of the science fiction movie “The Matrix.” The science fiction thriller “depicts a dystopian future in which reality as perceived by most humans is actually a simulated reality called ‘the Matrix,’ created by sentient machines to subdue the human population, while their bodies’ heat and electrical activity are used as an energy source. Computer programmer ‘Neo’ learns this truth and is drawn into a rebellion against the machines, which involves other people who have been freed from the ‘dream world.’”

The Matrix stars Keanu Reeves, as Neo, and the only way he could see the Matrix is to be unplugged by digesting a “red pill” offered to him by Morpheus, played by Lawrence Fishburne.

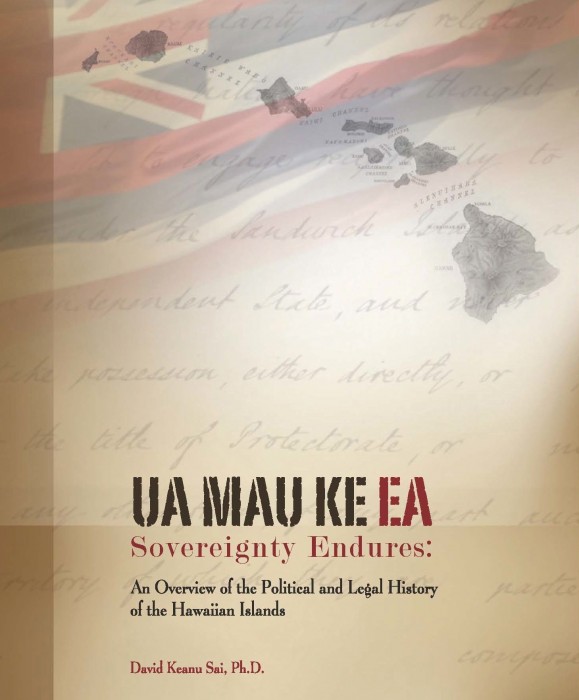

Dr. Sai is a political scientist whose academic research has exposed the American occupation of the Hawaiian Islands that began with the United States’ unlawful overthrow of the Hawaiian government in 1893 followed by the military occupation during the Spanish-American War. The American occupation is a subject taught in classes at the high schools and collegiate levels in Hawai‘i and abroad. He is the author of Ua Mau Ke Ea (Sovereignty Endures), a history book used in classroom instruction.

Dr. Sai is a political scientist whose academic research has exposed the American occupation of the Hawaiian Islands that began with the United States’ unlawful overthrow of the Hawaiian government in 1893 followed by the military occupation during the Spanish-American War. The American occupation is a subject taught in classes at the high schools and collegiate levels in Hawai‘i and abroad. He is the author of Ua Mau Ke Ea (Sovereignty Endures), a history book used in classroom instruction.

Dr. Sai also represented the Hawaiian Kingdom as lead Agent in international arbitration proceedings—Lance Paul Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, held at the Permanent Court of Arbitration. The Larsen case was also cited by the Arbitral Tribunal in its judgment in the land mark South China Sea case, which was also held at the Permanent Court of Arbitration. Dr. Sai has been likened to the character Neo.

The Matrix star Keanu Reeves is a cousin of Dr. Sai. Keanu Reeves’ father and Dr. Sai’s mother are first cousins and both were named after Dr. Sai’s maternal grandfather, Henry Keanu Reeves. Both men are Hawaiian.

Dr. Sai’s Exhibit “Hawaiʻi Reloaded – The Matrix Alive!!”

What if the place you lived in and all that you knew to be “truth” was suddenly turned upside down and inside out? What if your understanding of who you are and your place in the world was flipped in an instance? What if you were living a lie and everyone you know were all a part of the lie unknowingly? All this sounds like the Warner Bros. Hollywood blockbuster film the “Matrix.”

Hawai‘i’s political and social history since 1893 is the “Matrix” and it’s called the 50th State of the United States of America. In the nineteenth century, Hawai‘i was known as the Hawaiian Kingdom that was internationally recognized as an independent country with over ninety embassies and consulates throughout the world, which included an embassy in Washington, D.C. The “truth” is Hawai‘i was never a part of the United States, but rather has been under an illegal and prolonged occupation since the Spanish-American War in 1898.

Listen and experience the real history of Hawai‘i through the lens of the Matrix, and what is Hawai‘i’s future going forward.

What is truth, what is justice, what is reality? It’s time to get unplugged!

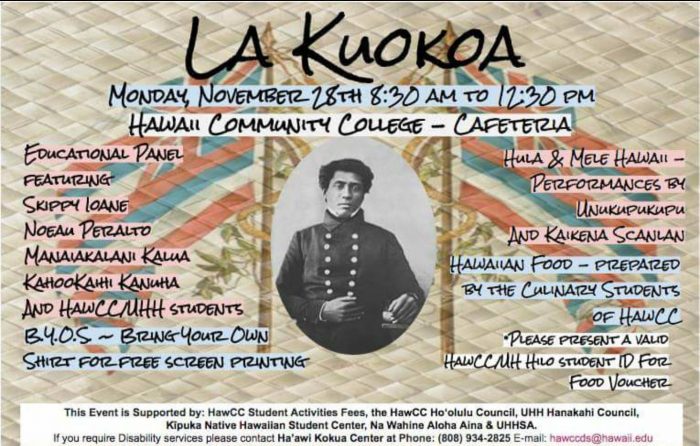

Today is July 31st which is a national holiday in the Hawaiian Kingdom called “Restoration day,” and it is directly linked to another holiday observed on November 28th called “Independence day.” Here is a brief history of these two celebrated holidays.

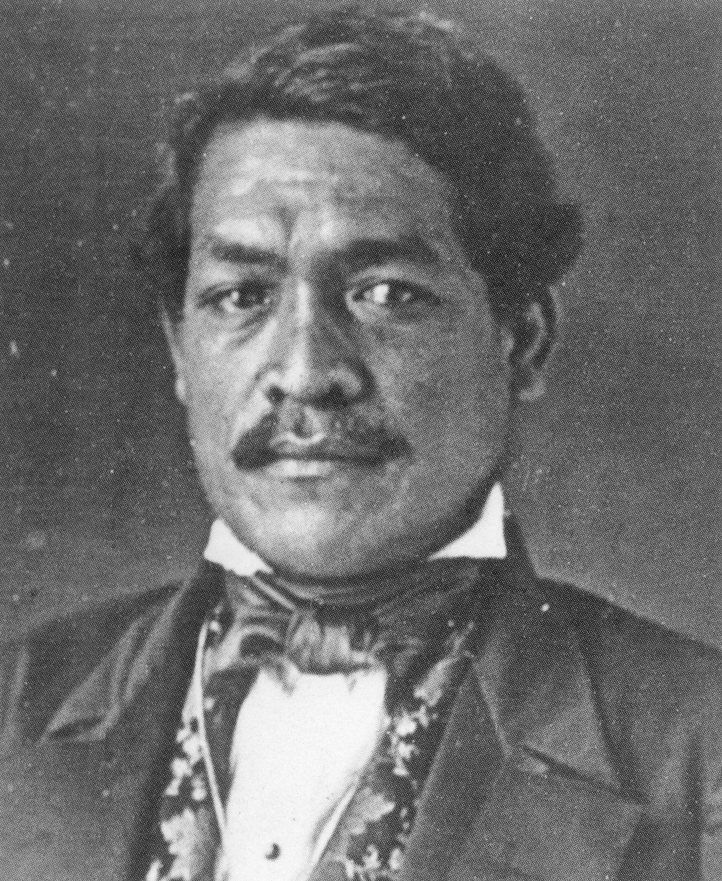

In the summer of 1842, Kamehameha III moved forward to secure the position of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a recognized independent state under international law. He sought the formal recognition of Hawaiian independence from the three naval powers of the world at the time—Great Britain, France, and the United States. To accomplish this, Kamehameha III commissioned three envoys, Timoteo Ha‘alilio, William Richards, who at the time was still an American Citizen, and Sir George Simpson, a British subject. Of all three powers, it was the British that had a legal claim over the Hawaiian Islands through cession by Kamehameha I, but for political reasons the British could not openly exert its claim over the other two naval powers. Due to the islands prime economic and strategic location in the middle of the north Pacific, the political interest of all three powers was to ensure that none would have a greater interest than the other. This caused Kamehameha III “considerable embarrassment in managing his foreign relations, and…awakened the very strong desire that his Kingdom shall be formally acknowledged by the civilized nations of the world as a sovereign and independent State.”

In the summer of 1842, Kamehameha III moved forward to secure the position of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a recognized independent state under international law. He sought the formal recognition of Hawaiian independence from the three naval powers of the world at the time—Great Britain, France, and the United States. To accomplish this, Kamehameha III commissioned three envoys, Timoteo Ha‘alilio, William Richards, who at the time was still an American Citizen, and Sir George Simpson, a British subject. Of all three powers, it was the British that had a legal claim over the Hawaiian Islands through cession by Kamehameha I, but for political reasons the British could not openly exert its claim over the other two naval powers. Due to the islands prime economic and strategic location in the middle of the north Pacific, the political interest of all three powers was to ensure that none would have a greater interest than the other. This caused Kamehameha III “considerable embarrassment in managing his foreign relations, and…awakened the very strong desire that his Kingdom shall be formally acknowledged by the civilized nations of the world as a sovereign and independent State.”

While the envoys were on their diplomatic mission, a British Naval ship, HBMS Carysfort, under the command of Lord Paulet, entered Honolulu harbor on February 10, 1843, making outrageous demands on the Hawaiian government. Basing his actions on complaints made to him in letters from the British Consul, Richard Charlton, who was absent from the kingdom at the time, Paulet eventually seized control of the Hawaiian government on February 25, 1843, after threatening to level Honolulu with cannon fire. Kamehameha III was forced to surrender the kingdom, but did so under written protest and pending the outcome of the mission of his diplomats in Europe. News

While the envoys were on their diplomatic mission, a British Naval ship, HBMS Carysfort, under the command of Lord Paulet, entered Honolulu harbor on February 10, 1843, making outrageous demands on the Hawaiian government. Basing his actions on complaints made to him in letters from the British Consul, Richard Charlton, who was absent from the kingdom at the time, Paulet eventually seized control of the Hawaiian government on February 25, 1843, after threatening to level Honolulu with cannon fire. Kamehameha III was forced to surrender the kingdom, but did so under written protest and pending the outcome of the mission of his diplomats in Europe. News  of Paulet’s action reached Admiral Richard Thomas of the British Admiralty, and he sailed from the Chilean port of Valparaiso and arrived in the islands on July 25, 1843. After a meeting with Kamehameha III, Admiral Thomas determined that Charlton’s complaints did not warrant a British takeover and ordered the restoration of the Hawaiian government, which took place in a grand ceremony on July 31, 1843. At a thanksgiving service after the ceremony, Kamehameha III proclaimed before a large crowd, ua mau ke ea o ka ‘aina i ka pono (the life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness). The King’s statement became the national motto.

of Paulet’s action reached Admiral Richard Thomas of the British Admiralty, and he sailed from the Chilean port of Valparaiso and arrived in the islands on July 25, 1843. After a meeting with Kamehameha III, Admiral Thomas determined that Charlton’s complaints did not warrant a British takeover and ordered the restoration of the Hawaiian government, which took place in a grand ceremony on July 31, 1843. At a thanksgiving service after the ceremony, Kamehameha III proclaimed before a large crowd, ua mau ke ea o ka ‘aina i ka pono (the life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness). The King’s statement became the national motto.

The envoys eventually succeeded in getting formal international recognition of the Hawaiian Islands “as a sovereign and independent State.” Great Britain and France formally recognized Hawaiian sovereignty on November 28, 1843 by joint proclamation at the Court of London, and the United States followed on July 6, 1844 by a letter of Secretary of State John C. Calhoun. The Hawaiian Islands became the first Polynesian nation to be recognized as an independent and sovereign State.

The ceremony that took place on July 31 occurred at a place we know today as “Thomas Square” park, which honors Admiral Thomas, and the roads that run along Thomas Square today are “Beretania,” which is Hawaiian for “Britain,” and “Victoria,” in honor of Queen Victoria who was the reigning British Monarch at the time the restoration of the government and recognition of Hawaiian independence took place.

My name is Dr. David Keanu Sai and from 1999-2001, I served as Agent for the Hawaiian Kingdom in international arbitration proceedings under the auspices of the Permanent Court of Arbitration, The Hague, Netherlands. The case was Lance Paul Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom (Larsen case). I was responsible for the drafting of the pleadings as well as communication with the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s (PCA) International Bureau-Secretariat, headed by a Secretary General, regarding the case. So I am very well acquainted with the case as well as what was going on behind the formalities of the case and the confines of the published Award in the International Law Reports, vol. 119, p. 566.

My name is Dr. David Keanu Sai and from 1999-2001, I served as Agent for the Hawaiian Kingdom in international arbitration proceedings under the auspices of the Permanent Court of Arbitration, The Hague, Netherlands. The case was Lance Paul Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom (Larsen case). I was responsible for the drafting of the pleadings as well as communication with the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s (PCA) International Bureau-Secretariat, headed by a Secretary General, regarding the case. So I am very well acquainted with the case as well as what was going on behind the formalities of the case and the confines of the published Award in the International Law Reports, vol. 119, p. 566.

I am also a lecturer at the University of Hawai‘i with a M.A. and a Ph.D. in political science specializing in international relations and public law. My doctoral research and published law articles centers on the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State under a prolonged occupation by the United States of America (United States) since the Spanish-American War.

After reviewing the two Awards by the Tribunal in the South China Sea case, I perused the Philippines’ Memorial and transcripts of the proceedings to find any reference to the Larsen case that was cited in Tribunal’s Award on Jurisdiction and Admissibility (paragraph 181) as well as the Award on the Merits (paragraph 157, footnote 98). In the Memorial, which is called a pleading in international proceedings, the Philippines brought up the Larsen case in paragraphs 5.125 and 5.126. It was also mentioned by Professor Philippe Sands, QC, in his expert testimony to the Tribunal during a hearing on jurisdiction on July 8, 2015, and found on page 123 of the transcripts. On the Larsen case, the Philippine Memorial stated:

5.125 The Monetary Gold principle has also been followed once in arbitral proceedings. An arbitral tribunal applied it propio motu in Larsen v. the Hawaiian Kingdom. In that case, a resident of Hawaii sought redress from “the Hawaiian Kingdom” for its failure to protect him from the United States and the State of Hawaii. The parties, who had agreed to submit their dispute to arbitration by the PCA, hoped that the tribunal would address the question of the international legal status of Hawaii. Both parties initially argued that the Monetary Gold principle should be confined to ICJ proceedings. The tribunal rejected that argument, stating that international arbitral tribunals “operate[ ]within the general confines of public international law and, like the International Court, cannot exercise jurisdiction over a State which is not a party to its proceedings”.

5.126 The tribunal ultimately decided that it was precluded from addressing the merits because the United States, which was absent, was an indispensable party. Relying on Monetary Gold, the tribunal explained that the legal interests of the United States would form “the very subject-matter” of a decision on the merits because it could not rule on the lawfulness of the conduct of the respondent, the Kingdom of Hawaii, without necessarily evaluating the lawfulness of the conduct of the United States. It emphasized that “[t]he principle of consent in international law would be violated if this Tribunal were to make a decision at the core of which was a determination of the legality or illegality of the conduct of a non-party”.

There is much said in these two paragraphs that may escape the layman who may not be familiar with Hawai‘i’s legal history and its place in international law. By the Philippines own admission it recognized the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a party to the arbitration, and without the participation of the United States, as an indispensable third party, the Philippines stated the Larsen Tribunal “could not rule on the lawfulness of the conduct of the respondent, the Kingdom of Hawaii.”

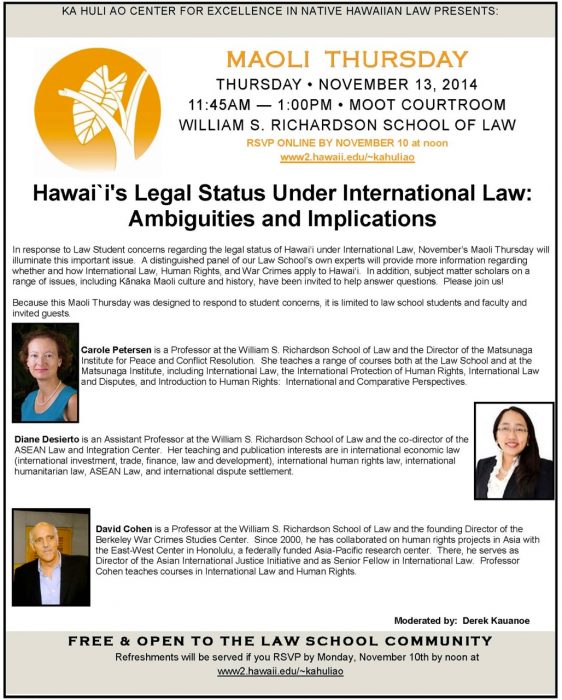

Here at the University of Hawai‘i William S. Richardson School of Law, a few faculty members, namely Dr. Diane Desierto, Dr. David Cohen, and Carol Peterson, have gone so far as to call the Larsen case mere puffery. But can the Larsen case be an exaggeration of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s continued existence under international law and the role of the principle of indispensable third parties when it comes to the United States, as claimed by these faculty members who admitted, at a closed forum, they don’t know the legal history of Hawai‘i?

Obviously, the Philippine Government did not think so, and nor did the Tribunal in the South China Sea arbitration. As a landmark case in international arbitration, the South China Sea arbitration has drawn attention to the Larsen case again, which gives me an opportunity to set the record straight in light of the detractors, but also for those who are just curious.

In the Larsen case, the Hawaiian Kingdom, which I served as Agent along with others on my legal team, was a “Defendant,” which in international proceedings is also called a “Respondent.” This means that the Hawaiian Kingdom was defending itself from the allegations made by Larsen, as the “Plaintiff,” which is also called a “Claimant,” that the Council of Regency was allowing the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws in the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom, which led to his unfair trial and subsequent incarceration.

By going to Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom at the PCA’s case repository, it identifies me as the Agent for the Hawaiian Kingdom, identifies the Hawaiian Kingdom as a “State,” and under the heading of “case description,” it provides the dispute as follows:

“Dispute between Lance Paul Larsen (Claimant) and The Hawaiian Kingdom (Respondent) whereby

The Philippines’ Memorial also cites an article by Bederman and Hilbert on the Larsen case that was originally published in the American Journal of International (vol. 95, p. 928), and republished the article in the Hawaiian Journal of Law and Politics (vol. 1, p. 82) that the Philippines cited. According to Bederman and Hilbert, who succinctly stated the dispute, “At the center of the PCA proceeding was…that the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist and that the Hawaiian Council of Regency (representing the Hawaiian Kingdom) is legally responsible under international law for the protection of Hawaiian subjects, including the claimant. In other words, the Hawaiian Kingdom was legally obligated to protect Larsen from the United States’ ‘unlawful imposition [over him] of [its] municipal laws’ through its political subdivision, the State of Hawaii. As a result of this responsibility, Larsen submitted, the Hawaiian Council of Regency should be liable for any international law violations that the United States committed against him.”

Clearly, the Larsen case was not about whether the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist, but was based on the presumption that it does exist, and, as such, a dispute arose between a Hawaiian national and the Hawaiian Government that stemmed from an illegal and prolonged occupation by the United States. My responsibility, as the Agent, was to defend the Hawaiian Government from Larsen’s allegation of allowing the imposition of American municipal laws in the Hawaiian Islands.

I was also keenly aware that before the PCA could establish the Arbitral Tribunal to preside over the dispute between Larsen and the Hawaiian Kingdom, it had to first confirm that the Hawaiian Kingdom as a “State” continues to exist in order for the PCA to exercise its “institutional jurisdiction” (United Nations Dispute Settlement, Permanent Court of Arbitration, p. 15) so that it could facilitate the creation of an ad hoc tribunal. By extension, the PCA also had to confirm that Larsen’s nationality was a Hawaiian subject, and the Council of Regency was the Hawaiian Government.

As an intergovernmental organization established under the 1899 Hague Convention, I, and the 1907 Hague Convention, I, the PCA facilitates the creation of ad hoc arbitral tribunals to settle disputes between two or more States, i.e., the Philippines v. China, or between a State and a private entity, i.e., Romak, S.A. v. Uzbekistan. Romak, S.A. is a Swiss company that specializes in the sale of grain and cereal products. In both cases, the States have to exist in fact and not in theory in order for the PCA to have institutional jurisdiction. Disputes must be “international” and not “municipal,” which are disputes that go before national courts of States and not international courts or tribunals.

Since the arbitration agreement between Larsen and the Hawaiian Government was submitted to the PCA on November 8, 1999, the PCA was doing their due diligence as to whether the Hawaiian Kingdom currently exists as a State under international law. If the Hawaiian Kingdom does not exist then this fact would negate the existence of the nationality of Larsen as a Hawaiian subject and the existence of the Council of Regency as the Hawaiian government, and, therefore, the dispute.

After its due diligence, however, the PCA could not deny that the Hawaiian Kingdom did exist as an independent State, and, along with other treaties, the Hawaiian Kingdom had a treaty with the Netherlands, which houses the PCA itself. However, what faced the PCA is that it could not find any evidence that the Hawaiian Kingdom had ceased to exist under international law. Only by way of a “treaty of cession,” whereby the Hawaiian Kingdom agreed to merge itself into the territory of the United States, could the Hawaiian Kingdom have been extinguished under international law.

There was never a treaty, except for American municipal laws, enacted by the United States Congress, that treat Hawai‘i as if it were annexed. Municipal laws are not international laws, as between States, but are laws that are limited in scope and authority to the territory of the State that enacted them. In other words, an American municipal law could no more annex the Hawaiian Kingdom, than it could annex the Netherlands.

My legal team and Larsen’s attorney knew this and operated on the “presumption” that the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist until evidence shows otherwise. This was the  same conclusion that the PCA came to, which prompted a telephone conversation I had with the PCA’s Secretary General, Tjaco T. van den Hout, in February 2000. In that telephone conversation, he recommended that the Hawaiian Government along with Larsen’s Counsel, Ms. Ninia Parks, provide a formal invitation to the United States Government to join in the arbitration. I recall his specific words to me on this matter. He said that in order to maintain the integrity of this case, he recommended that the Hawaiian Government, with the consent of Larsen’s legal representative, provide a formal invitation to the United States to join in the current arbitration. He then requested that I provide evidence that the invitation was made so that it can be made a part of the record for the case.

same conclusion that the PCA came to, which prompted a telephone conversation I had with the PCA’s Secretary General, Tjaco T. van den Hout, in February 2000. In that telephone conversation, he recommended that the Hawaiian Government along with Larsen’s Counsel, Ms. Ninia Parks, provide a formal invitation to the United States Government to join in the arbitration. I recall his specific words to me on this matter. He said that in order to maintain the integrity of this case, he recommended that the Hawaiian Government, with the consent of Larsen’s legal representative, provide a formal invitation to the United States to join in the current arbitration. He then requested that I provide evidence that the invitation was made so that it can be made a part of the record for the case.

This invitation would elicit one of the three possible responses: first, the United States accepts the invitation, which recognizes the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom and its government and will have to answer to its unlawful imposition of American municipal laws that led to Larsen’s unfair trial and incarceration; second, the United States denies the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom because Hawai‘i is the so-called 50th State of the Federal Union and demands that the PCA cease and desist in entertaining the dispute; or, third, the United States denies the invitation to join in the arbitration but does not deny the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the dispute between a Hawaiian national and the government representing the Hawaiian Kingdom.

On March 3, 2000, a conference call meeting was held with John Crook from the United States State Department in Washington, D.C., together with myself representing the Hawaiian Government and Ms. Parks representing Larsen. After the meeting, I drafted a letter to Crook that covered what was discussed in the meeting regarding the invitation and a carbon copy was sent to Secretary General van den Hout, as he requested, so that it could be placed on the record that an invitation was made. A few days later the United States Embassy in The Hague notified the PCA that they denied the invitation to join in the  arbitration, but requested permission from the Hawaiian Government and Ms. Parks, on behalf of Larsen, to have access to all pleadings and transcripts of the case. Both Ms. Parks and I were individually contacted by telephone from the PCA’s Deputy Secretary General, Phyllis Hamilton, of the request made by the US Embassy, which we both consented to. It was also agreed that the records of the proceedings would be open to the public.

arbitration, but requested permission from the Hawaiian Government and Ms. Parks, on behalf of Larsen, to have access to all pleadings and transcripts of the case. Both Ms. Parks and I were individually contacted by telephone from the PCA’s Deputy Secretary General, Phyllis Hamilton, of the request made by the US Embassy, which we both consented to. It was also agreed that the records of the proceedings would be open to the public.

The United States took the third option and did not deny the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Thereafter, the PCA began to form the Arbitral Tribunal the following month in April of 2000. Memorials were filed with the Tribunal by Larsen on May 22, 2000, and the Hawaiian Government on May 25, 2000. The Hawaiian Government then filed its Counter-Memorial on June 22, 2000, and Larsen its Counter-Memorial on June 23, 2000.

After the pleadings were submitted, the Tribunal issued Procedural Order no. 3 on July 17, 2000. In the Procedural Order, the Tribunal articulated the dispute from the pleadings in the following statement.

The Tribunal further stated in the Procedural Order that it “is concerned whether the first issue does in fact raise a dispute between the parties, or, rather, a dispute between each of the parties and the United States over the treatment of the plaintiff by the United States. If it is the latter, that would appear to be a dispute which the Tribunal cannot determine, inter alia because the United States is not a party to the agreement to arbitrate.” The Tribunal, therefore, stated that it could not get to the merits of the case regarding “redress against the Respondent Government” as the second issue, until it address the first issue that Larsen’s “rights as a Hawaiian subject are being violated…by the United States of America.” This first issue that the Tribunal was asked to determine is what caused the Tribunal to raise the principle of an “indispensable third party” that stemmed from the Monetary Gold case. In other words, could the Tribunal proceed to rule on the lawfulness of the conduct of the Hawaiian Government when its judgment would imply an evaluation of the lawfulness of the conduct of the United States, which is not a party to the case.

The Tribunal scheduled oral hearings to be held at the PCA on December 7, 8 and 11, 2000.

https://vimeo.com/17007826

A day before the oral hearings were to begin on December 7, the three arbitrators met with myself and legal team and Ms. Parks in the PCA to go over the schedule and what we can expect. What they also provided to us were booklets of the decisions by the International Court of Justice, namely the Monetary Gold Removed from Rome in 1943 (Italy v. the United Kingdom, France and the United States), Case Concerning Certain Phosphate Land in Nauru (Nauru v. Australia), and Case Concerning East Timor (Portugal v. Australia).

All three cases centered on the indispensable third party principle and that we should be prepared to respond as to how this case can proceed without the participation of the United States. In the Monetary Gold case it was on the non-participation of Albania; the Nauru Case was the non-participation of New Zealand and the United Kingdom; and the East Timor case was the non-participation of Indonesia. Of the three cases, only the Nauru case could proceed because the ICJ concluded that New Zealand and the United Kingdom were not indispensable third parties.

After two days of hearings, it was evident that the Tribunal would not be able to adjudge and declare, according to Procedural Order no. 3, that Larsen’s “rights as a Hawaiian subject are being violated…by the United States of America,” because the United States was not a party to the proceedings. Without a decision by the Tribunal that finds Larsen’s rights are being violated, he would be unable to get to the second issue of having the Tribunal declare and adjudge that he “does have ‘redress against the Respondent Government’ in relation to these violations.” In light of this, I knew that Larsen would not prevail in these proceedings without the participation of the United States. On the final day of the hearings, December 11, I decided to ask the Tribunal to make a determination on a topic that I felt would not violate the indispensable third party principle that was at the center of these proceedings.

The Hawaiian Government needed a pronouncement by the Tribunal as to the legal status of the Hawaiian Kingdom under international law that would deny the lawfulness of American municipal laws within Hawaiian territory. In other words, the Hawaiian Government needed a pronouncement of international law that could be cited as a bar to American municipal laws from being applied in Hawaiian territory. This fundamental bar of one State’s municipal laws to be applied within the territory of another State centers on the legal meaning of “independence.”

In international arbitration between the Netherlands and the United States at the PCA (Island of Palmas case), the arbitrator explained what the term independence means in  international law. In the Award (p. 8), Judge Max Huber stated, “Sovereignty in the relations between States signifies independence. Independence in regard to a portion of the globe is the right to exercise therein, to the exclusion of any other State, the functions of a State. The development of the national organization of State during the last few centuries and, as a corollary, the development of international law, have established this principle of the exclusive competence of the State in regard to its own territory.”

international law. In the Award (p. 8), Judge Max Huber stated, “Sovereignty in the relations between States signifies independence. Independence in regard to a portion of the globe is the right to exercise therein, to the exclusion of any other State, the functions of a State. The development of the national organization of State during the last few centuries and, as a corollary, the development of international law, have established this principle of the exclusive competence of the State in regard to its own territory.”

Oppenheim, International Law, Vol. 1, p. 177-8 (2nd ed. 1912), explains: “Sovereignty as supreme authority, which is independent of any other earthly authority, may be said to have different aspects. As excluding dependence from any other authority, and in especial from the authority of the another State, sovereignty is independence. It is external independence with regard to the liberty of action outside its borders in the intercourse with other States which a State enjoys. It is internal independence with regard to the liberty of action of a State inside its borders. As comprising the power of a State to exercise supreme authority over all persons and things within its territory, sovereignty is territorial supremacy. As comprising the power of a State to exercise supreme authority over its citizens at home and abroad, sovereignty is personal supremacy. For these reasons a State as an International Person possesses independence and territorial and personal supremacy.”

With this in mind, I made the following statement and request to the Tribunal that is provided in the transcripts of the final day of the hearings on December 11.

The issue before the Tribunal was whether Larsen could hold to account the Hawaiian Government for allowing the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws within Hawaiian territory that led to his unfair trial and subsequent incarceration. My request of the Tribunal on the last day of the oral hearings was to have the Tribunal acknowledge and pronounce the legal status of Hawai‘i under international law as an “independent State,” which, as a co-equal, the United States could not impose its municipal laws within Hawaiian territory without violating international law.

My intent, was to move beyond the dispute with Larsen and address the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws across the entire territory of Hawai‘i and everyone affected by it, not just Larsen. I understood that my request of the Tribunal would not violate the indispensable third party principle, because for the Tribunal to make this pronouncement there would be no need to address the lawfulness or unlawfulness of the conduct of the United States, but merely to acknowledge historical facts.

My request of the Tribunal was similar to the Philippines request of the South China Sea Tribunal to determine whether or not the landmasses in the South China Sea are islands or rocks. The Philippines argued that since it is merely a determination of facts, the Tribunal would not be getting into the lawfulness or unlawfulness of the conduct of States regarding the sovereignty over these islands. The sovereign claims over these land masses would be whether the land masses are islands as defined under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea that establish a maritime zone, or are they rocks that would not establish the maritime zones. According to Article 121(3) of the Convention, an island must “sustain human habitation or economic life of [its] own” in order to generate maritime zones, i.e., the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of 200 miles from its coast. This is how the Philippines successfully argued why the principle of indispensable third parties would not apply.

On February 5, 2001, the Tribunal issued the Award on Jurisdiction, and concluded that the United States was an indispensable third party. In paragraph 12.5, the Tribunal explained, “It follows that the Tribunal cannot determine whether the [Hawaiian Kingdom] has failed to discharge its obligation towards [Lance Larsen] without ruling on the legality of the acts of the United States of America. Yet that is precisely what the Monetary Gold principle precludes the Tribunal from doing. As the International Court of Justice explained in the East Timor case, ‘the Court could not rule on the lawfulness of the conduct of a State when its judgment would imply an evaluation of the lawfulness of the conduct of another State which is not a party to the case.’”

The Tribunal, however, did answer my request, which is provided in paragraph 7.4 of the Award. The Tribunal stated, “A perusal of the material discloses that in the nineteenth century the Hawaiian Kingdom existed as an independent State recognised as such by the United States of America, the United Kingdom and various other States, including by exchanges of diplomatic or consular representatives and the conclusion of treaties.” By using the phrase, “a perusal of the material,” the Tribunal made it clear that its conclusion that the United States recognized the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State was drawn from the facts of the case.

By declaring that the United States recognized “the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State,” is another way of stating that the United States recognized that only Hawaiian laws could be applied in Hawaiian territory and not the municipal laws of the United States. Through these international proceedings, the Hawaiian Government was able to broaden the impact of an unlawful occupation beyond the Larsen case to now include all persons that have been victimized by the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws within the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

The Award of the South China Sea arbitration’s reference of the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom is recognition of the integrity of the Larsen case itself and why it is now a precedent case regarding the principle of indispensable third parties along with the Monetary Gold case and the East Timor case. It is also an acknowledgment of the caliber of those individuals who served as arbitrators, two of which are now serving as Judges on the International Court of Justice, namely Judge Christopher Greenwood and Judge James Crawford, who served as President of the Tribunal.

When I entered the University of Hawai‘i Political Science Department to get my M.A. and Ph.D. I also planned to address the misinformation regarding Hawai‘i as the 50th State of the American Union and the categorization of native Hawaiians as indigenous people as defined under United Nations documents. This is a false narrative that has already been rebuked by the mere fact of the Larsen case, which has now become a precedent case in international law. This information about the Hawaiian Kingdom has made people very uncomfortable, but that’s what happens when you’re faced with the truth.

The recent South China Sea arbitration, being a landmark case, has cited the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom case as one of the international precedents on “indispensable third parties” along with the Monetary Gold Removed from Rome in 1943 case and East Timor case in its Arbitral Award on Jurisdiction and Admissibility (paragraph 181). This is a significant achievement for the Hawaiian Kingdom in international law.

On July 12, 2016, the Arbitral Tribunal in the South China Sea Arbitration (The Republic of the Philippines v. the People’s Republic of China), established under the auspices of the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA), issued its decision in The Hague, Netherlands. The decision found that China’s claims over manmade islands in the South China Sea have no legal basis. Its decision was based on the definition of an “island” under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (1982) (Convention).

According to Article 121(3) of the Convention, an island must “sustain human habitation or economic life of [its] own” in order to generate maritime zones, i.e., the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of 200 miles from its coast. Therefore, China’s creation of islands were never islands to begin with but rather reefs or rocks, which precluded China from claiming any maritime zones. For background of the dispute visit the New York Times “Philippines v. China, Q. and A. on South China Sea.”

At first glance, it would appear that China contested the jurisdiction of the Arbitral Tribunal in a Position Paper it drafted on December 7, 2014, and on this basis refused to participate in the proceedings held at the PCA in The Hague, Netherlands. So how is it possible that the Arbitral Tribunal pronounces a ruling against China when it hasn’t participated in the arbitration?

The simple answer is that the Arbitral Tribunal could issue a ruling because China “did” participate in the proceedings and has consented to PCA’s authority to establish the Tribunal by virtue of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (1982). As noted in the PCA’s press release, the PCA currently has 12 other cases established under Annex VII of the Law of the Sea Convention. China is a State party to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, and arbitration is recognized as a means to settle disputes under Annex VII.

As a State party to the Convention, China consented to arbitration even if it chose not to participate, but it did signify its participation when it made its position public regarding the arbitration proceedings. According to the Arbitral Tribunal in its Arbitral Award on Jurisdiction and Admissibility, it stated in paragraph 11, “the non-participation of China does not bar this Tribunal from proceeding with the arbitration. China is still a party to the arbitration, and pursuant to the terms of Article 296(1) of the Convention and Article 11 of the Annex VII, it shall be bound by any award the Tribunal issues.”

What is not commonly understood is that there are two matters of jurisdiction in cases that come before the PCA. The first is “institutional jurisdiction” of the PCA, and the second is “subject matter jurisdiction” of the Arbitral Tribunal over the particular dispute.

As an intergovernmental organization established under the 1899 Hague Convention, I, and the 1907 Hague Convention, I, the PCA facilitates the creation of ad hoc Arbitral Tribunals to settle disputes between two or more States (interstate), between a State and an international organization, between two or more international organizations, between a State and a private entity, or between an international organization and a private entity (United Nations Dispute Settlement, Permanent Court of Arbitration, p. 15). Disputes must be “international” and not “municipal,” which are disputes that go before national courts of States and not international courts or tribunals.

An explanation of the PCA’s institutional jurisdiction is also provided in the South China Sea case press release. On page 3 the press release the PCA states, “The Permanent Court of Arbitration is an intergovernmental organization established by the 1899 Hague Convention on the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes. The PCA has 121 Members States. Headquartered at the Peace Palace in The Hague, the Netherlands, the PCA facilitates arbitration, conciliation, fact-finding, and other dispute resolution proceedings among various combinations of States, State entities, intergovernmental organizations, and private parties.” China became a member State of the PCA on Nov. 21, 1904, and the Philippines on Sep. 12, 2010.

The “institutional jurisdiction” was satisfied by the PCA because both the Philippines and China are States, which makes it an interstate arbitration, and both are parties to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, which under Annex VII provides for arbitration of disputes under the Convention. It was under this provision that the PCA could establish the Arbitral Tribunal.

The first matter that the Tribunal had to address was whether it had “subject matter jurisdiction” over the dispute, which it found that it did. In paragraph 146 of the Arbitral Award, the Tribunal stated, “China’s Position Paper was said by the Chinese Ambassador to have “comprehensively explain[ed] why the Arbitral Tribunal…manifestly has no jurisdiction over the case.” In its Procedural Order No. 4, para. 1.1 (21 April 2015), the Tribunal explained, “the communications by China, including notably its Position Paper of 7 December 2015 and the Letter of 6 February 2015 from the Ambassador of the People’s Republic of China to the Netherlands, effectively constitute a plea concerning this Arbitral Tribunal’s jurisdiction for the purposes of Article 20 of the Rules of Procedure and will be treated as such for the purposes of this arbitration.”

In this initial phase of jurisdiction, the Tribunal, however, also had to deal with the rule of “indispensable third parties” which applied to States that are not participating in the arbitration and whose rights could be affected by the Tribunal’s decision. These States were Viet Nam, Malaysia, Indonesia and Brunei. This rule would not apply to China since the Tribunal recognized China’s participation. Paragraph 157 of the Arbitral Award addressed the indispensable third-party rule, i.e. Viet Nam, which states, “The Tribunal noted that this arbitration differs from past cases in which a court or tribunal has found the involvement of a third party to be indispensable. The Tribunal recalled that ‘the determination of the nature of and entitlements generated by the maritime features in the South China Sea does not require a decision on issues of territorial sovereignty’ and held accordingly that ‘[t]he legal rights and obligation of Viet Nam therefore do not need to be determined as a prerequisite to the determination of the merits of the case.'”

In other words, the Tribunal was going to determine in accordance with the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, whether or not the reefs and rocks in the South China Sea constitute the definition of islands as defined under the Convention, which would determine whether or not it had a territorial sea of 12 miles and an EEZ (Exclusive Economic Zone) of 200 miles. It would not be determining matters of sovereignty over the islands. If they weren’t islands, but rather reefs or rocks, then China’s claims to a territorial sea and an EEZ would become irrelevant. The Arbitral Award determined that they were not islands as defined under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea.

Of importance in these proceedings is that the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom was specifically referenced in the Award on Jurisdiction in paragraph 181, which was also referenced in the Arbitral Award, paragraph 157, footnote 98. In the Award on Jurisdiction, the Tribunal stated, “The present situation is different from the few cases in which an international court or tribunal has declined to proceed due to the absence of an indispensable third-party, namely in Monetary Gold Removed from Rome in 1943 and East Timor before the International Court of Justice and in the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom arbitration. In all of those cases, the rights of the third States (respectively Albania, Indonesia, and the United States of America) would not have been affected by a decision in the case, but would have ‘form[ed] the very subject matter of the decision.’ Additionally, in those cases the lawfulness of activities by third States was in question, whereas here none of the Philippines’ claims entail allegations of unlawful conduct by Viet Nam or other third States.”

In the Larsen case, the PCA exercised its “institutional jurisdiction” when it convened the Arbitral Tribunal, because it recognized that the Hawaiian Kingdom is a “State” in a dispute with a Hawaiian subject who was a “private entity.” Like the South China Sea case, once the Tribunal was convened, it had to address whether or not it had subject matter jurisdiction over the dispute between Larsen and the Hawaiian Kingdom, because of the fact that the United States was not a party.

This dispute was specifically stated in the arbitration agreement that the PCA based its institutional jurisdiction. Paragraph 2.1 of the Arbitral Award states, “(a) Lance Paul Larsen, Hawaiian subject, alleges that the Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom is in continual violation of its 1849 Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation with the United States of America, and in violation of the principles of international law laid [down] in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 1969, by allowing the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws over claimant’s person within the territorial jurisdiction of the Hawaiian Kingdom; (b) Lance Paul Larsen, a Hawaiian subject, alleges that the Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom is also in violation of the principles of international comity by allowing the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws over the claimant’s person within the territorial jurisdiction of the Hawaiian Kingdom.”

What was at the center of the dispute was the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws within the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom. The Tribunal was not established to determine whether or not the Hawaiian Kingdom exists as a “State,” which was already recognized by the PCA prior to establishing the Tribunal under its mandate of ensuring it had “institutional jurisdiction” in the first place.

According to the American Journal of International Law (vol. 95, p. 928), “At the center of the PCA proceeding was…that the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist and that the Hawaiian Council of Regency (representing the Hawaiian Kingdom) is legally responsible under international law for the protection of Hawaiian subjects, including the claimant. In other words, the Hawaiian Kingdom was legally obligated to protect Larsen from the United States’ ‘unlawful imposition [over him] of [its] municipal laws’ through its political subdivision, the State of Hawaii. As a result of this responsibility, Larsen submitted, the Hawaiian Council of Regency should be liable for any international law violations that the United States committed against him.” If the Hawaiian Kingdom did not exist as a State, the PCA would not have established the Arbitral Tribunal to address the dispute.

In these proceedings, however, the Council of Regency was attempting to get the Tribunal to pronounce the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom and even try to see if the Tribunal could issue some interim measures of protection. This was deliberately done to show that the Hawaiian Kingdom was taking affirmative steps, even during the proceedings, to do what it could in addressing the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws within Hawaiian territory, which led to Larsen’s unfair criminal trial and subsequent incarceration.

In the Arbitral Award, the Tribunal concluded that the United States was an indispensable third party. In paragraph 12.5, the Tribunal explained, “It follows that the Tribunal cannot determine whether the [Hawaiian Kingdom] has failed to discharge its obligation towards [Lance Larsen] without ruling on the legality of the acts of the United States of America. Yet that is precisely what the Monetary Gold principle precludes the Tribunal from doing. As the International Court of Justice explained in the East Timor case, ‘the Court could not rule on the lawfulness of the conduct of a State when its judgment would imply an evaluation of the lawfulness of the conduct of another State which is not a party to the case.'” It is clear that the Tribunal recognized the Hawaiian Kingdom as a “State” and the lawfulness of its conduct, and the United States as a “third State” and the lawfulness of its conduct.

UPDATE: Dr. Sai providing expert testimony in State of Hawai‘i v. Kinimaka that the State of Hawai‘i criminal court lacks competent jurisdiction.

Queen Lili‘uokalani was very familiar with the constitutional order of the Hawaiian Kingdom. On April 10, 1877, Lili‘uokalani was appointed by King Kalakaua as his heir-apparent and confirmed by the Nobles of the Legislative Assembly. Article 22, 1864 Constitution, provides, that the heir-apparent shall be who “the Sovereign shall appoint with the consent of the Nobles, and publicly proclaim as such during the King’s life.”

When she was Princess and heir-apparent, she served as the executive monarch, in the capacity of Regent, for ten months  when King Kalakaua departed on his world tour on January 20, 1881. Article 33 provides, “It shall be lawful for the King at any time when he may be about to absent himself from the Kingdom, to appoint a Regent or Council of Regency, who shall administer the Government in His name.” She also served as Regent when Kalakaua departed for California on November 5, 1890. On January 20, 1891, Kalakaua died in San Francisco. Nine days later, Lili‘uokalani was pronounced Queen after Kalakaua’s body returned to Honolulu on January 29.

when King Kalakaua departed on his world tour on January 20, 1881. Article 33 provides, “It shall be lawful for the King at any time when he may be about to absent himself from the Kingdom, to appoint a Regent or Council of Regency, who shall administer the Government in His name.” She also served as Regent when Kalakaua departed for California on November 5, 1890. On January 20, 1891, Kalakaua died in San Francisco. Nine days later, Lili‘uokalani was pronounced Queen after Kalakaua’s body returned to Honolulu on January 29.

Under Hawaiian constitutional law, the office of executive monarch is both head of state and head of government, which is unlike the British monarch, who is the head of state, and the Prime Minister is the head of government. The Hawaiian executive monarch is similar to the United States presidency. As such, she would have been very familiar with the workings of government as well as its constitutional limitations. More importantly, she would have understood the limits of United States municipal laws that were unlawfully imposed in the Hawaiian Islands in 1900, and the effect it would have on the jurisdiction of American territorial courts.

Not surprisingly, this was reflected in her deed of trust dated December 2, 1909. She stated that, “Trustees shall make an annual report to the Grantor during her lifetime, and after her death to a court of competent jurisdiction.” She further stated that, “a new trustee or trustees shall be appointed by the judge of a court of competent jurisdiction.” A court of competent jurisdiction is a court that has the legal authority to do a particular act.

Her explicit use of the term “court of competent jurisdiction” is very telling, especially when other Ali‘i trusts established under the constitutional order of the Hawaiian Kingdom, namely the Lunalilo Trust in 1874 and the Pauahi Bishop Trust in 1884, which the Queen was well aware of, specifically provided that annual reports must be given to the Supreme Court of the Hawaiian Kingdom for administrative oversight, and that the Hawaiian Supreme Court was vested with the authority to appoint the trustees.

The Queen did not state the “Supreme Court of the Territory of Hawai‘i” in her deed of trust, but rather “a court of competent jurisdiction.” These provisions in her deed of trust also imply that there are courts in Hawai‘i that are without competent jurisdiction, which were the courts of the American Territory of Hawai‘i that existed at the time she drew up her deed of trust in 1909.

The courts of the Territory of Hawai‘i derived their authority under the 1900 Act to provide a government for the Territory of Hawaii. The predecessor of the Territory of Hawai‘i was the Republic of Hawai‘i, which the United States Congress in its 1993 Joint Resolution—To acknowledge the 100th anniversary of the January 17, 1893 overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii, and to offer an apology to Native Hawaiians on behalf of the United States for the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii concluded was “self-declared.” The Republic of Hawai‘i’s predecessor was the provisional government, whom President Grover Cleveland reported to the Congress on December 18, 1893, as being “neither de facto nor de jure,” but self-declared as well. Furthermore, Queen Lili‘uokalani, in her June 20, 1894 protest to the United States referred to the provisional government as a “pretended government of the Hawaiian Islands under whatever name,” that enacted and enforced “pretended ‘laws’ subversive of the first principles of free government and utterly at variance with the traditions, history, habits, and wishes of the Hawaiian people.”

As the successor to the Territory of Hawai‘i, the courts of the State of Hawai‘i derive their authority from an Act to provide for the admission of the State of Hawaii into the Union. Both the 1900 Territorial Act and the 1959 Statehood Act are municipal laws of the United States, which is defined as pertaining “solely to the citizens and inhabitants of a state, and is thus distinguished from…international law (Black’s Law, 6th ed., p. 1018).” In order for these laws to be applied over the Hawaiian Islands, international law, which are “laws governing the legal relations between nations (Black’s Law, 6th ed., p. 816),” requires the cession of Hawaiian territory to the United States by a treaty prior to the enactment of these municipal laws. Without a treaty of cession, the Hawaiian Islands remain outside of United States territory, and therefore beyond the reach of United States municipal laws.

Oppenheim, International Law, vol. I, 285 (2nd ed.), explains that, cession of “State territory is the transfer of sovereignty over State territory by the owner State to another State.” He further states that the “only form in which a cession can be effected is an agreement embodied in a treaty between the ceding and the acquiring State (p. 286).” There exists no treaty of cession where the United States acquired the territory of the Hawaiian Islands under international law. Instead, the United States claims to have acquired the Hawaiian Islands in 1898 by a Joint Resolution—To provide for annexing the Hawaiian Islands to the United States. Like the 1900 Territorial Act and the 1959 Statehood Act, the 1898 Joint Resolution of Annexation is a municipal law of the United States, which has no effect beyond the territorial borders of the United States.

In 1936, the United States Supreme Court, in United States v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp., 299 U.S. 304, 318, stated, “Neither the Constitution nor the laws passed in pursuance of it have any force in foreign territory.” The following year, the Supreme Court, in United States v. Belmont, 301 U.S. 324, 332 (1937), again reiterated that the United States “Constitution, laws and policies have no extraterritorial operation unless in respect of our own citizens.” These two cases merely reiterated what the Supreme Court, in The Apollon, 22 U.S. 362, 370, stated in 1824 when the Court addressed whether or not a municipal law of the United States could be applied over a French ship—The Apollon, in waters outside of U.S. territory. In that case, the Supreme Court stated, “The laws of no nation can justly extend beyond its own territories except so far as regards its own citizens.”

Although the 1898 Joint Resolution of Annexation has conclusive phraseology that makes it appear that the Hawaiian Islands were indeed annexed, the act of annexation, which is the acquisition of territory from a foreign state, could not have been accomplished because it is still a municipal law of the United States that has no extraterritorial effect. In other words, a treaty is a bilateral instrument, whereby one state cedes territory to another state, thus consummating annexation in the receiving State, but the 1898 Joint Resolution of Annexation is a unilateral act that is claiming annexation occurred without a cession evidenced by a treaty.

As a replacement for a treaty that signifies consent by the ceding State, the resolution instead provides the following phrase: “Whereas the Government of the Republic of Hawaii having, in due form, signified its consent, in the manner provided by its constitution, to cede absolutely and without reserve to the United States of America all rights of sovereignty of whatsoever kind in and over the Hawaiian Islands and their dependencies.” In The Apollon, the Supreme Court also addressed phraseology in United States municipal laws, which is quite appropriate and instructive in the Hawaiian situation. The Supreme Court stated, “however general and comprehensive the phrases used in our municipal laws may be, they must always be restricted in construction to places and persons, upon whom the legislature has authority and jurisdiction (p. 370).”

It would be ninety years later, in 1988, when the United States Department of Justice, Office of Legal Counsel, would stumble over this American dilemma in a memorandum opinion written for the Legal Advisor for the Department of State regarding legal issues raised by the proposed Presidential proclamation to extend the territorial sea from a three mile limit to twelve. After concluding that only the President and not the Congress possesses “the constitutional authority to assert either sovereignty over an extended territorial sea or jurisdiction over it under international law on behalf of the United States (p. 242),” the Office of Legal Counsel also concluded that it was “unclear which constitutional power Congress exercised when it acquired Hawaii by joint resolution. Accordingly, it is doubtful that the acquisition of Hawaii can serve as an appropriate precedent for a congressional assertion of sovereignty over an extended territorial sea (p. 262).”

The opinion cited United States constitutional scholar Westel Woodbury Willoughby, The Constitutional Law of the United States, vol. 1, §239, 427 (2d ed.), who wrote in 1929, “The constitutionality of the annexation of Hawaii, by a simple legislative act, was strenuously contested at the time both in Congress and by the press. The right to annex by treaty was not denied, but it was denied that this might be done by a simple legislative act. …Only by means of treaties, it was asserted, can the relations between States be governed, for a legislative act is necessarily without extraterritorial force—confined in its operation to the territory of the State by whose legislature enacted it.” Nine years earlier in 1910, Willoughby, The Constitutional Law of the United States, vol. 1, §154, 345, wrote, “The incorporation of one sovereign State, such as was Hawaii prior to annexation, in the territory of another, is…essentially a matter falling within the domain of international relations, and, therefore, beyond the reach of legislative acts.”

Since January 17, 1893, there have been no courts of competent jurisdiction in the Hawaiian Islands. Instead, genocide has taken place through denationalization whereby the national pattern of the United States has been unlawfully imposed in the territory of an occupied sovereign State in violation of international humanitarian law.

UPDATE

On April 29, 2016, Dr. Keanu Sai served as an expert witness for the defense represented by Dexter Kaiama, Esquire, during an evidentiary hearing in criminal case State of Hawai‘i v. Kinimaka. Kaiama filed a motion to dismiss the criminal complaint on the grounds that the court lacks subject matter jurisdiction because the court derives its authority from the 1959 Statehood Act, which is a municipal law enacted by the United States Congress that has no effect beyond the borders of the United States.

In response to the Court denying the motion to dismiss in light of the fact that the prosecution did not refute any of the evidence provided in the evidentiary hearing, Kaiama is preparing to file a motion for interlocutory appeal to the Intermediate Court of Appeals. Because the prosecution did not provide any rebuttable evidence against the evidence presented by the defense that provided a legal and factual basis for concluding that the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist as an independent and sovereign State that has been under an illegal and prolonged occupation, the trial Court should have dismissed the case. If there was to be any appeal it would be the prosecution and not the defense. Denying a person of a fair and regular trial is a war crime under Article 147, 1949 Geneva Convention, IV.

https://vimeo.com/167266060

In a move to bring international attention to the humanitarian crisis in the Hawaiian Islands as a result of the United States prolonged and illegal occupation since the Spanish-American War, a Complaint was submitted to the United Nations Human Rights Council (Council) on May 23, 2016. Dr. Keanu Sai represents the complainant, Kale Kepekaio Gumapac, as his attorney-in-fact. Dr. Sai also represents Gumapac before Swiss authorities regarding war crimes. Additional documents that accompanied the Complaint, included: War Crimes Report: Humanitarian Crisis in the Hawaiian Islands by Dr. Sai, his Declaration and Curriculum Vitae.

In a move to bring international attention to the humanitarian crisis in the Hawaiian Islands as a result of the United States prolonged and illegal occupation since the Spanish-American War, a Complaint was submitted to the United Nations Human Rights Council (Council) on May 23, 2016. Dr. Keanu Sai represents the complainant, Kale Kepekaio Gumapac, as his attorney-in-fact. Dr. Sai also represents Gumapac before Swiss authorities regarding war crimes. Additional documents that accompanied the Complaint, included: War Crimes Report: Humanitarian Crisis in the Hawaiian Islands by Dr. Sai, his Declaration and Curriculum Vitae.

“The lodging of the complaint was two-fold,” explains Dr. Sai. “First, the complaint will draw attention to the prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom, which has created a humanitarian crisis of unimaginable proportions never before seen. Second, the purpose of the complaint is to report the war crimes committed against Kale Gumpac by Deutsche Bank, officials of the State of Hawai‘i, and others, which is now before the Swiss Federal Criminal Court. As a victim of war crimes, Mr. Gumapac is one of thousands, if not millions of victims who reside in Hawai‘i under an illegal foreign occupation.”

“The lodging of the complaint was two-fold,” explains Dr. Sai. “First, the complaint will draw attention to the prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom, which has created a humanitarian crisis of unimaginable proportions never before seen. Second, the purpose of the complaint is to report the war crimes committed against Kale Gumpac by Deutsche Bank, officials of the State of Hawai‘i, and others, which is now before the Swiss Federal Criminal Court. As a victim of war crimes, Mr. Gumapac is one of thousands, if not millions of victims who reside in Hawai‘i under an illegal foreign occupation.”

The Council was established in 2006 by the United Nations General Assembly and was formerly known as the United Nations Commission on Human Rights. The General Assembly gave the Council two main responsibilities: (a) promote universal respect for the protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms for all, without distinction of any kind and in a fair and equal manner; and (b) address situations of violations of human rights, including gross and systematic violations, and make recommendations to resolve them. The Council is comprised of 47 member States of the United Nations who are elected by the United Nations General Assembly for a term of three years.

The Council has a human rights mandate, but has also included as part of its mandate international humanitarian law. International human rights law are rights inherent in all human beings, whatever their nationality, place of residence, sex, national or ethnic origin, color, religion, language, or any other status. These rights are expressed in treaties such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. International humanitarian law is a set of rules to protect civilians and non-combatants during an armed conflict, which includes military occupation. Humanitarian law is expressed in treaties such as the 1907 Hague Convention, IV, and the 1949 Geneva Convention, IV.

In the past, it was thought that human rights law applied only during peace time and humanitarian law applied only during armed conflict, but current international law recognizes that both bodies of law are considered as complementary sources of obligations in situations of armed conflict. In its 2008 Resolution 9/9—Protection of the human rights of civilians in armed conflict, the Council emphasized “that conduct that violates international humanitarian law, including grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, or of the Protocol Additional there of 8 June 1977 relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I), may also constitute a gross violation of human rights.”

The Council then reiterated “that effective measures to guarantee and monitor the implementation of human rights should be taken in respect of civilian populations in situations of armed conflict, including people under foreign occupation, and that effective protection against violations of their human rights should be provided, in accordance with international human rights law and applicable international humanitarian law, particularly Geneva Convention IV relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, of 12 August 1949, and other international instruments.”

Accompanying the Complaint is a War Crime Report that provides a comprehensive narrative of Hawai‘i’s legal and political history since the nineteenth century to the present. In the Report, Dr. Sai explains, “The Report will answer, in the affirmative, three fundamental questions that are quintessential to the current situation in the Hawaiian Islands:

After answering these questions in the affirmative, Dr. Sai would then conclude that the UNHRC has the authority to investigate the complaint “under the complaint procedure provided for in paragraph 87 of the annex to Human Rights Council resolution 5/1.”

Before providing the facts of Gumapac’s case, the Complaint gives a short summary of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s continued existence as a State under international law, and that this status was explicitly recognized by the Secretariat of the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in Lance Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom (1999-2001).

In the Complaint, Dr. Sai states, “Since the occupation began, the United States engaged in the criminal conduct of genocide under humanitarian law through denationalization. After local institutions of Hawaiian self-government were destroyed by the United States through its installed insurgency, a United States pattern of administration was imposed in 1900, whereby the former Hawaiian national character was obliterated.”

Dr. Sai went on to provide a pattern of criminal conduct in violation of international humanitarian law: “The United States interfered with the methods of education; compelled education in the English language; banned the use of Hawaiian, being the national language, in the schools; compulsory or automatic granting of United States citizenship upon Hawaiian nationals; imposed conscription of Hawaiian nationals into the armed forces of the United States; imposed the duty of swearing the oath of allegiance; confiscated and destroyed property of Hawaiian nationals for militarization; pillaged the property and estates of Hawaiian nationals; imposed American administrative and judicial systems; imposed American financial and economic administration; colonized Hawaiian territory with nationals of the United States; permeated the economic life through individuals whose nationality and/or allegiance was American; and denied Hawaiian nationals of aboriginal blood their vested right to health care at no charge at Queen’s Hospital, which was established by the Hawaiian government for that purpose.”

The Complaint calls upon the Council to take action without haste and recommends the Council to:

Additionally, the Council oversees a process called Universal Periodic Review (UPR), which involves a review of the human rights records of all member States of the United Nations, which includes its record of complying with international humanitarian law. In UPRs, the Council decided in its Resolution 5/1 that “given the complementary and mutually interrelated nature of international human rights law and international humanitarian law, the review shall taken into account applicable international humanitarian law.”

In the Complaint, Dr. Sai also draws attention to the UPR done on the United States in 2015. “The February 6, 2015 Report of the United States submitted to the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights in Conjunction with the Universal Periodic Review deliberately withheld information of the Hawaiian Kingdom despite the United States’ full and complete knowledge of arbitration proceedings held under the auspices of the PCA, and where the Secretariat of the PCA explicitly recognized the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom.”

Dr. Sai further states that “the draft report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review of the United States dated May 21, 2015, and the final report of the United Nations Human Rights Council adopted on September 24, 2015, omits any mention of the Hawaiian Kingdom as well.” Instead, the 2015 UPR of the United States treats native Hawaiians as an indigenous people, which, under United Nations instruments, are nations of people that are non-States and reside within the territory of a State, such as Native American tribes. Common words that are associated with indigenous people include terms such as self-determination, colonization, and decolonization.

The 2015 UPR reflects the deception that has been perpetuated by the United States in order to conceal its prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom that has now lasted for over a century, and the genocide of the Hawaiian citizenry who have been led to believe that aboriginal Hawaiians are an indigenous people that have been colonized by the United States. In the Complaint, Dr. Sai states, “Hawaiian nationals of aboriginal blood are not indigenous people as defined under United Nations instruments, but are defined under Hawaiian Kingdom law as Hawaiian subjects who comprise the majority of the national population.”

The American occupation of Hawai‘i is the longest occupation in the history of international relations, and it will be a shock for the international community to find out that the United States seized an internationally recognized neutral country in order to bolster its military, and carried out a policy of genocide through denationalization in violation of international humanitarian law. This policy that was carried out in 1900 resulted in the obliteration of Hawaiian national consciousness among the citizenry of the Hawaiian Kingdom in less then two generations.

https://vimeo.com/168241369

Dr. Lynette Cruz interviews Dr. Sai on the topic of genocide through denationalization on her television show, Issues that Matter. Dr. Sai explains the difference between international humanitarian law and human rights law, and how genocide has and continues to occur through denationalization of Hawaiian subjects.

The following protest by Queen Lili‘uokalani dated June 20, 1894 was lodged with the United States Secretary of State Walter G. Gresham. The protest was delivered by H.A. Widemann on June 22, 1894 to United States diplomat Albert S. Willis, assigned to the American Legation in Honolulu. Queen Lili‘uokalani’s protest centers on the events that transpired in January 1893 on the pretext of war and the creation of a pretended government.

The following protest by Queen Lili‘uokalani dated June 20, 1894 was lodged with the United States Secretary of State Walter G. Gresham. The protest was delivered by H.A. Widemann on June 22, 1894 to United States diplomat Albert S. Willis, assigned to the American Legation in Honolulu. Queen Lili‘uokalani’s protest centers on the events that transpired in January 1893 on the pretext of war and the creation of a pretended government.

January 17, 1893, was the first armed conflict between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States of America. The second armed conflict would occur on August 12, 1898 when the Hawaiian Kingdom would be unlawfully occupied by the United States during the Spanish-American War.

The pretended government installed by the United States on January 17, 1893, calling itself the provisional government, would change its name to the Republic of Hawai‘i in 1894, to the Territory of Hawai‘i in 1900, and finally to the State of Hawai‘i in 1959.

**************************************************

His Excellency

W.G. Gresham

Secretary of State

Washington, D.C.

To His Excellency

Albert S. Willis

U.S. Envoy Extraordinary Minister Plenipotentiary.

Sir,