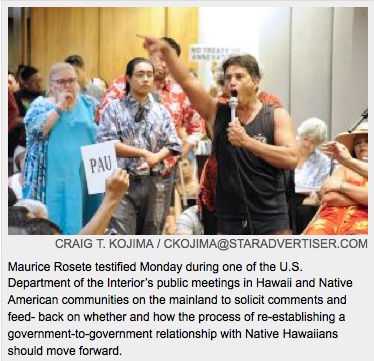

The hearings held by the U.S. Department of Interior throughout the Hawaiian Islands are attracting both Hawaiians and non-Hawaiians to give testimony—the sleeping giant has awakened. What is astonishing is the level of legal sophistication and historical accuracies displayed by those giving their testimony. Combined with emotions, these testimonies are eerily similar to the voices of Hawaiians documented in an article in the September 30, 1897 publication of the San Francisco Call newspaper.

This is a re-posting of a blog entry on January 29, 2014.

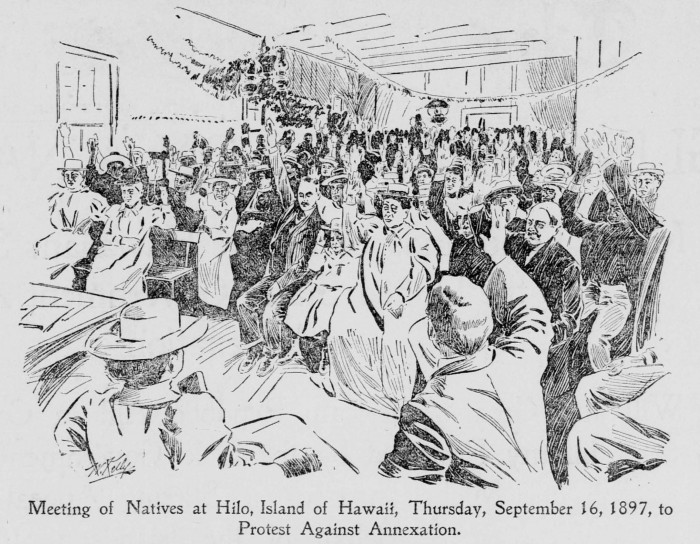

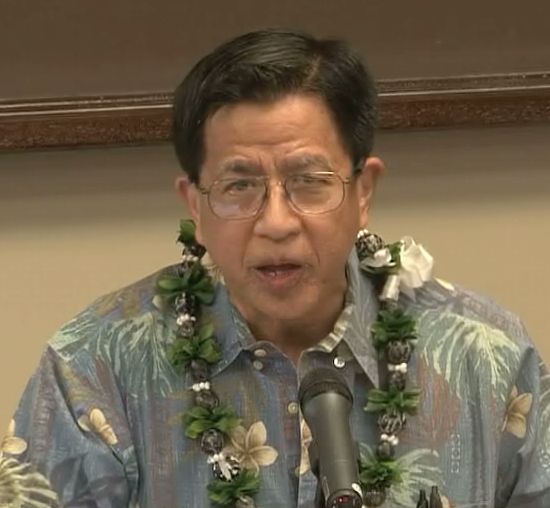

The article was published and authored by Miriam Michelson who was an American journalist and writer. It was written as Michelson was leaving Honolulu harbor on board the Steamship Australia heading to San Francisco. Michelson was sent to the Hawaiian Islands to do a story on annexation. Her story centers on a signature petition against annexation being gathered throughout the islands by the Hawaiian Patriotic League (Hui Aloha ‘Aina) and she bears witness to one of those meetings in the city of Hilo on the Island of Hawai‘i.

The article was published and authored by Miriam Michelson who was an American journalist and writer. It was written as Michelson was leaving Honolulu harbor on board the Steamship Australia heading to San Francisco. Michelson was sent to the Hawaiian Islands to do a story on annexation. Her story centers on a signature petition against annexation being gathered throughout the islands by the Hawaiian Patriotic League (Hui Aloha ‘Aina) and she bears witness to one of those meetings in the city of Hilo on the Island of Hawai‘i.

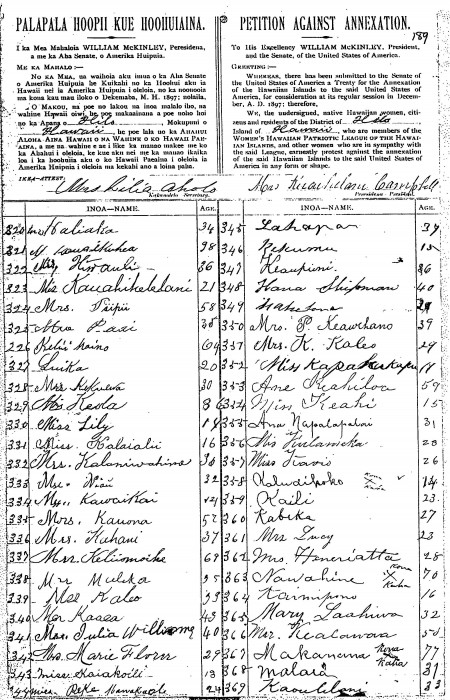

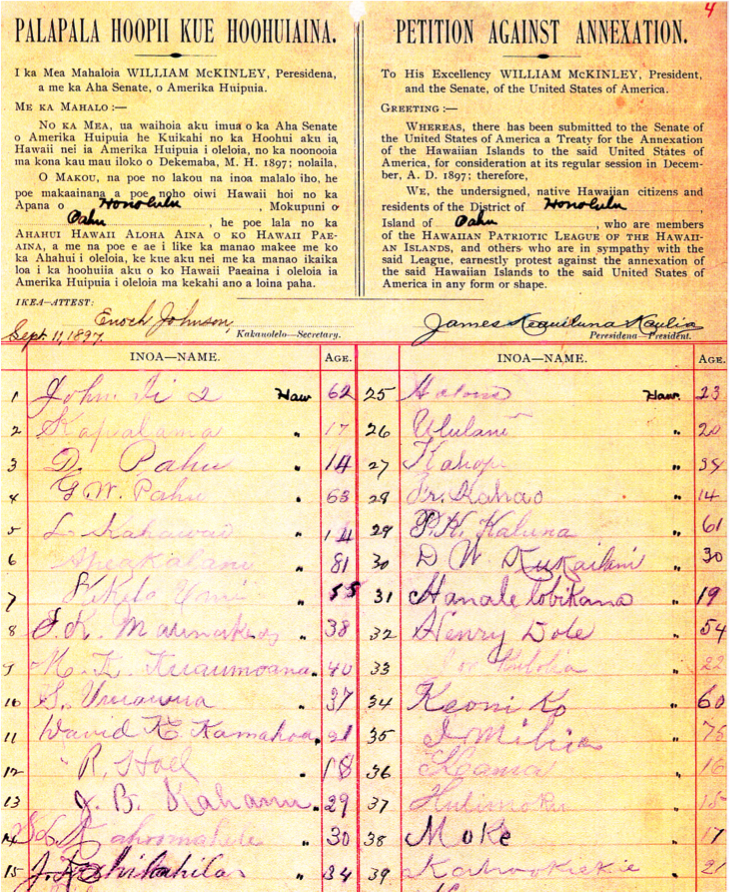

It is a powerful article that speaks to the issue of annexation from the Hawaiian perspective and the article’s title clearly speaks to the veracity of what the reader will read. Not known at the time, however, was whether or not the signature petitions would prevent the United States Senate from ratifying the so-called treaty of  annexation. Before the Senate convened in December of 1897, officers of the Hawaiian Patriotic League and the Hawaiian Political Association traveled to Washington, D.C. and met with Senator George Hoar of Massachusetts. Senator Hoar agreed to submit the signature petition onto the record of the Senate when it convened, and by March of 1898, the signature petition successfully killed the treaty as the Senate was unable to garner enough votes for ratification.

annexation. Before the Senate convened in December of 1897, officers of the Hawaiian Patriotic League and the Hawaiian Political Association traveled to Washington, D.C. and met with Senator George Hoar of Massachusetts. Senator Hoar agreed to submit the signature petition onto the record of the Senate when it convened, and by March of 1898, the signature petition successfully killed the treaty as the Senate was unable to garner enough votes for ratification.

Here follows a snippet of the article, which is quite lengthy, but you can read it in its entirety by going to this link and downloading the entire article in PDF format. “Strangling Hands Upon A Nations Throat”

*****************************************************

The strongest memory I have of the islands is connected with the hall of the Salvation Army at Hilo, on the Island of Hawaii. It’s a crude little place, which holds about 300 people, I should think. The rough, uncovered rafters show above, and the bare walls are relieved only by Scriptural admonitions in English and Hawaiian:

“Boast not thyself of to-morrow.” “Without Christ there is no salvation.”

As I entered, the bell on the foreign church, up on one of the beautiful Hilo hills, was striking ten. The place was packed with natives, and outside stood a patient crowd unable to enter. It was a women’s meeting, but there were many men present. The women were dressed in Mother Hubbards of calico or cloth and wore sailor hats—white or black. The men were in coats and trousers of American make.

Presently the crowd parted and two women walked in, both very tall, dressed in handsome free-flowing trained gowns of black crepe-braided in black. They wore black kid gloves and large hats of black straw with black feathers. The taller of the two—a very queen in dignity and repose—wore nodding red roses in her hat, and about her neck and falling to the waist a long, thick necklace of closely strung, deep-red, coral-like flowers, with delicate ferns interspersed.

This was Mrs. Kuaihelani Campbell, the president of the Women’s Hawaiian Patriotic League. Her companion was the secretary of the branch in Hilo.

It was almost pitiful to note the reception of these two leaders—the dumb, almost adoring fondness in the women’s eyes; the absorbed, close interest in the men’s dark heavy faces.

After the enthusiasm had subsided the minister of the Hawaiian church arose. He is tall, blonde, fair faced, three-quarters white, as they say here. Clasping his hands in front and looking down over the bowed dark heads before him he made the short opening prayer. He held himself well, his sentences were short and his manner was simple.

There is something wonderfully effective in earnest prayer delivered in an ancient language with which one is unfamiliar. One hears not words, but tones. His feelings, not his reason, are appealed to. Freed of the limiting effects of stereotyped phrases the imagination supplies the sense. Like the Hebrew and the Latin the Hawaiian tongue seems to touch the primitive sources of one’s nature, to strip away the complicated armor with which civilization and worldliness have clothed us and to leave the emotions bare for that wonderful instrument, a man’s deep voice, to play upon.

The minister closed and a deep murmuring “Amen” from the people followed.

I watched Mrs. Emma Nawahi curiously as she rose to address the people. I have never heard two women talk in public in quite the same way. Would this Hawaiian woman be embarrassed or timid, or self-conscious or assertive?

Not any of these. Her manner had the simple directness that made Charlotte Perkins Stetson, two years ago, the most interesting speaker of the Woman’s Congress. But Mrs. Stetson’s pose is the most artistic of poses—a pretense of simplicity. This Hawaiian woman’s thoughts were of her subject, not of herself. There was an interesting impersonality about her delivery that kept my eyes fastened upon her while the interpreter at my side whispered his translation in short, detached phrases, hesitating now and then for a word, sometimes completing the thought with a gesture.

“We are weak people, we Hawaiians, and have no power unless we stand together,” read Mrs. Nawahi, frequently raising her eyes from her paper and at times altogether forgetting it.

“We are weak people, we Hawaiians, and have no power unless we stand together,” read Mrs. Nawahi, frequently raising her eyes from her paper and at times altogether forgetting it.

“The United States is just—a land of liberty. The people there are the friends, the great friends of the weak. Let us tell them—let us show them that as they love their country and would suffer much before giving it up, so do we love our country, our Hawaii, and pray that they do not take it from us.”

“Our one hope is in standing firm—shoulder to shoulder, heart to heart. The voice of the people is the voice of God. Surely that great country across the ocean must hear our cry. By uniting our voices the sound will be carried on so they must hear us.”

“In this petition, which we offer for your signature to-day, you, women of Hawaii, have a chance to speak your mind. The men’s petition will be sent on by the men’s club as soon as the loyal men of Honolulu have signed it. There is nothing underhand, nothing deceitful in our way—our only way—of fighting. Everybody may see and may know of our petition. We have nothing to conceal. We have right on our side. This land is ours—our Hawaii. Say, shall we lose our nationality? Shall we be annexed to the United States? Aole loa. Aole loa.”

It didn’t require the interpreter’s word to make me understand the response. One could read negation, determination in every intent, dark face.

“Never!’ they say,” the man beside me muttered. “Never! they say. ‘No! No!’ they say-”

But the presiding officer, a woman, was introducing Mrs. Campbell to the people. Her large mouth parted in a pleased smile as the men and women stamped and shouted. She spoke only a few words, good-naturedly, hopefully. Once its seemed as though she were talking them all in her confidence, so sincere and soft was her voice as she leaned forward.

“Stand firm, my friends. Love of country means more to you and to me than anything else. Be brave; be strong. Have courage and patience. Our time will come. Sign this petition—those of you who love Hawaii. How many—how many will sign?”

“Stand firm, my friends. Love of country means more to you and to me than anything else. Be brave; be strong. Have courage and patience. Our time will come. Sign this petition—those of you who love Hawaii. How many—how many will sign?”

She held up a gloved hand as she spoke, and in a moment the palms of hundreds of hands were turned toward her.

They were eloquent, those deep lined, broad, dark hands, with their short fingers and worn nails. They told of poverty, of work, of contact with the soil they claim. The woman who presided had said a few words to the people, when all at once I saw a thousand curious eyes turned upon me.

“What is it?” I asked the interpreter. “What did she say?”

He laughed. “‘A reporter is here,’ she says. She says to the people, ‘Tell how you feel. Then the Americans will know. Then they may listen.’”

A remarkable scene followed. One by one men and women rose and in a sentence or two in the rolling, broad voweled Hawaiian made a fervent profession of faith.

“My feeling,” declared a tall, broad-shouldered man, whose dark eyes were alight with enthusiasm. “This is my feeling: I love my country and I want to be independent—now and forever.”

“And my feeling is the same,” cried a stout, bold-faced woman, rising in the middle of the hall. “I love this land. I don’t want to be annexed.”

“This birthplace of mine I love as the American loves his. Would he wish to be annexed to another, greater land?”

“I am strongly opposed to annexation. How dare the people of the United States rob a people of their independence?”

“I want the American Government to do justice. America helped to dethrone Liliuokalani. She must be restored. Never shall we consent to annexation!”

“My father is American; my mother is pure Hawaiian. It is my mother’s land I love. The American nation has been unjust. How could we ever love America?”

“Let them see their injustice and restore the monarchy!” cried an old, old woman, whose dark face framed in its white hair was working pathetically.

“If the great nations would be fair they would not take away our country. Never will I consent to annexation!”

“Tell America I don’t want annexation. I want my Queen,” said the gentle voice of a woman.

“That speaker is such a good woman,” murmured the interpreter. “A good Christian, honest, kind and charitable.”

“I’m against annexation—myself and all my family.”

“I speak for those behind me,” shouted a voice from far in the rear. “They cannot come in—they cannot speak. They tell me to say, ‘No annexation. Never.’”

I am Kauhi of Kalaoa. We call it Middle Hilo. Our club has 300 members. They have sent me here. We are all opposed to annexation—all—all!”

He was a young man. His open coat showed his loose dark shirt; his muscular body swayed with excitement. He wore boots that came above his knees. There was a large white handkerchief knotted about his brown throat, and his fine head, with its intelligent eyes, rose from his shoulders with a grace that would have been deerlike were it not for its splendid strength.

“I love my country and oppose annexation,” said a heavy-set, gray-haired man with a good, clear profile. “We look to America as our friend. Let her not be our enemy!”

“Hekipi, a delegate from Molokai to the league, writes: ‘I honestly assert that the great majority of Hawaiians on Molokai are opposed to annexation. They fear that if they become annexed to the United States they will lose their lands. The foreigners will reap all the benefit and the Hawaiians will be placed in a worse position than they are to-day.”

“I am a mail carrier. Come with me to my district.” A man who was sitting in the first row rose and stretched out an appealing hand. “Come to my district. I will show you 2000 Hawaiians against annexation.”

“I stand—we all stand to testify to our love of our country. No flag but the Hawaiian flag. Never the American!”

There was cheering at this, and the heavy, sober, brown faces were all aglow with excited interest.

I sat and watched and listened.

At Honolulu I had asked a prominent white man to give me some idea of the native Hawaiian’s character.

“They won’t resent anything,” he said, contemptuously. “They haven’t a grain of ambition. They can’t feel even envy. They care for nothing but easy and extremely simple living. They have no perseverance, no backbone. They’re unfit.”

Yet surely here was no evidence of apathy, of stupid forbearance, of characterless cringing.

These men and women rose quickly one after another, one interrupting the other at times, and then standing expectantly waiting his turn—too simple, too sincere, it seemed to me, to feel self-conscious or to study for a moment about the manner of his speech, so vital was the matter delivered.

They stood as all other Hawaiians stand—with straight shoulders splendidly thrown back and head proudly poised. Some held their roughened, patient hands clasped, some bent and looked toward me, as though I were a sort of magical human telephone and phonograph combined.

I might misunderstand a word or two of the interpreted message, but there was no mistaking those earnest, brown faces and beseeched dark eyes, which seemed to try to bridge the distance my ignorance of their language and their slight acquaintance with mine created between us.

I verily believe that even the most virulent of annexationists would have thought these Hawaiians human; almost worthy of consideration.

The people rose now and sang the majestic Hawaiian National Hymn. It was sung fervently, a full, deep chorus of hundreds of voices. The music is beautifully characteristic, with its strong, deep bass chords to which the women’s plaintive, uncultivated voices answer. Then there was a benediction, and the people passed out into the muddy street.