https://vimeo.com/100486404

Awakening the Sleeping Giant! A discussion with Dr. Keanu Sai and the recent D.O.I. Hearing in Hawaii and How we need to transition from Kuʻe to Kulia I Ka Nuʻu.

https://vimeo.com/100486404

Awakening the Sleeping Giant! A discussion with Dr. Keanu Sai and the recent D.O.I. Hearing in Hawaii and How we need to transition from Kuʻe to Kulia I Ka Nuʻu.

Hawaii News Now – KGMB and KHNL

HONOLULU (HawaiiNewsNow) – The debate over whether native Hawaiians should fight for sovereignty continues, and during the gubernatorial debate on Hawaii News Now between Governor Neil Abercrombie and state Senator David Ige, Governor Abercrombie stated that the Hawaiian kingdom does not exist.

While it may have not been a big shock to some, the governor’s comments have created discussions throughout communities and social media, with some stating his comments are ignorant and he is unaware of Hawaii’s history.

Political scientist Dr. Keanu Sai has completed doctoral research that is mainly focused on Hawaii’s continued existence as an independent and sovereign country, and has also had success in the Permanent Court of Arbitration concerning the dispute between the acting government of the Hawaiian Kingdom and a Hawaiian national.

Steve Uyehara was joined on Sunrise by Dr. Keanu Sai, who shared his thoughts and comments.

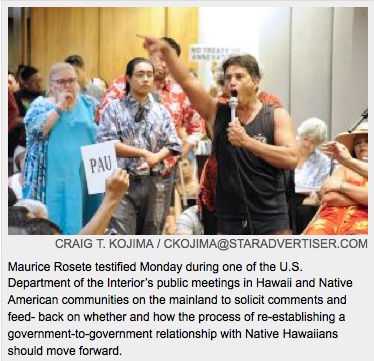

July 2, 2014 the United States Department of the Interior meeting in Keaukaha to take public testimony on 5 questions regarding establishing a government to government relationship. An overwhelming number of people showed up to testify at all meetings across the state and almost all testified “no” to all 5 questions. This is the meeting in Keauaha on Hawai’i Island.

https://vimeo.com/99608323

Professor Williamson Chang visits Kanaka Express and explains the Organic Act to the Lahui.

There has been recent attention drawn to Andrew Walden’s article titled “Liliuokalani 1895: “Monarchy is Forever Ended, Republic of Hawaii is only lawful Government.” He claims the monarchy had ended in 1895 and that the Republic of Hawai‘i had become the lawful government. What Walden leaves out of his article is that the Republic of Hawai‘i, who the United States Congress in its Apology resolution in 1993 called “self-declared,” was comprised of insurgents. After completing a presidential investigation into the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government by United States forces, President Cleveland secured an executive agreement with Queen Lili‘uokalani to grant amnesty after the Hawaiian Kingdom government was restored under the 1893 Agreement of restoration. The failure of the President to carry out the Agreement of restoration, being an international treaty, is what allowed the insurgency to increase its unlawful power and control over the Hawaiian Islands. What is also interesting is that Walden admits that Lili‘uokalani was still Queen after the so-called overthrow of January 17, 1893.

There has been recent attention drawn to Andrew Walden’s article titled “Liliuokalani 1895: “Monarchy is Forever Ended, Republic of Hawaii is only lawful Government.” He claims the monarchy had ended in 1895 and that the Republic of Hawai‘i had become the lawful government. What Walden leaves out of his article is that the Republic of Hawai‘i, who the United States Congress in its Apology resolution in 1993 called “self-declared,” was comprised of insurgents. After completing a presidential investigation into the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government by United States forces, President Cleveland secured an executive agreement with Queen Lili‘uokalani to grant amnesty after the Hawaiian Kingdom government was restored under the 1893 Agreement of restoration. The failure of the President to carry out the Agreement of restoration, being an international treaty, is what allowed the insurgency to increase its unlawful power and control over the Hawaiian Islands. What is also interesting is that Walden admits that Lili‘uokalani was still Queen after the so-called overthrow of January 17, 1893.

Walden also fails to mention that the Queen was not an absolute Monarch, but rather a constitutional monarch limited and confined to Hawaiian law as the Chief Executive, which was distinct from the Judicial and Legislative branches of Hawaiian government. The Queen, as Chief Executive, could no more terminate the Hawaiian Kingdom by threat of insurgents, than the President, as Chief Executive of the United States, could terminate the Republic by threat of terrorists.

So according to this logic, if terrorists somehow kidnap the President of the United States and have him sign an abdication of the Republic of the United States and recognizes Al Qaeda as the lawful government in order to save the lives of some of his countrymen, the United States of America ceases to exist? This is a ridiculous notion, but it could be a great story line for an episode of “24: Live Another Day.” Putting all fun aside, the best explanation of the crisis would come from the law and from the Queen herself in her autobiography “Hawai‘i’s Story by Hawai‘i’s Queen” (1898). Under Chapters XLIII and XLIV the Queen explained in her own words:

I am Placed Under Arrest

On the sixteenth day of January, 1895, Deputy Marshal Arthur Brown and Captain Robert Waipa Parker were seen coming up the walk which leads from Beretania Street to my residence. Mrs. Wilson told me that they were approaching. I directed her to show them into the parlor, where I soon joined them. Mr. Brown informed me that he had come to serve a warrant for my arrest; he would not permit me to take the paper which he held, nor to examine its contents.

It was evident they expected me to accompany them; so I made preparations to comply, supposing that I was to be taken at once to the station-house to undergo some kind of trial. I was informed that I could bring Mrs. Clark with me if I wished, so she went for my hand-bag; and followed by her, I entered the carriage of the deputy marshal, and was driven through the crowd that by this time had accumulated at the gates of my residence at Washington Place. As I turned the corner of the block on which is built the Central Congregational church, I noticed the approach from another direction of Chief Justice Albert F. Judd; he was on the sidewalk, and was going toward my house, which he entered. In the mean time the marshal’s carriage continued on its way, and we arrived at the gates of Iolani Palace, the residence of the Hawaiian sovereigns.

We drove up to the front steps, and I remember noticing that troops of soldiers were scattered all over the yard. The men looked as though they had been on the watch all night. They were resting on the green grass, as though wearied by their vigils; and their arms were stacked near their tents, these latter having been pitched at intervals all over the palace grounds. Staring directly at us were the muzzles of two brass field pieces, which looked warlike and formidable as they pointed out toward the gate from their positions on the lower veranda. Colonel J. H. Fisher came down the steps to receive me; I dismounted, and he led the way up the staircase to a large room in the corner of the palace. Here Mr. Brown made a formal delivery of my person into the custody of Colonel Fisher, and having done this, withdrew.

Then I had an opportunity to take a survey of my apartments. There was a large, airy, uncarpeted room with a single bed in one corner. The other furniture consisted of one sofa, a small square table, one single common chair, and iron safe, a bureau, a chiffonier, and a cupboard, intended for eatables, made of wood with wire screening to allow the circulation of the air through the food. Some of these articles may have been added during the days of my imprisonment. I have portrayed the room as it appears to me in memory. There was, adjoining the principal apartment, a bath-room, and also a corner room and a little boudoir, the windows of which were large, and gave access to the veranda.

Colonel Fisher spoke very kindly as he left me there, telling me that he supposed this was to be my future abode; and if there was anything I wanted I had only to mention it to the officer, and that it should be provided. In reply, I informed him that there were one or two of my attendants whom I would like to have near me, and that I preferred to have my meals sent from my own house. As a result of this expression of my wishes, permission was granted to my steward to bring me my meals three times each day.

That first night of my imprisonment was the longest night I have ever passed in my life; it seemed as though the dawn of day would never come. I found in my bag a small Book of Common Prayer according to the ritual of the Episcopal Church. It was a great comfort to me, and before retiring to rest Mrs. Clark and I spent a few minutes in the devotions appropriate to the evening.

Here, perhaps, I may say, that although I had been a regular attendant on the Presbyterian worship since my childhood, a constant contributor to all the missionary societies, and had helped to build their churches and ornament the walls, giving my time and my musical ability freely to make their meetings attractive to my people, yet none of these pious church members or clergymen remembered me in my prison. To this (Christian?) conduct I contrast that of the Anglican bishop, Rt. Rev. Alfred Willis, who visited me from time to time in my house, and in whose church I have since been confirmed as a communicant. But he was not allowed to see me at the palace.

Outside of the rooms occupied by myself and my companion there were guards stationed by day and by night, whose duty it was to pace backward and forward through the hall, before my door, and up and down the front veranda. The sound of their never-ceasing footsteps as they tramped on their beat fell incessantly on my ears. One officer was in charge, and two soldiers were always detailed to watch our rooms. I could not but be reminded every instant that I was a prisoner, and did not fail to realize my position. My companion could not have slept at all that night; her sighs were audible to me without cessation; so I told her the morning following that, as her husband was in prison, it was her duty to return to her children. Mr. Wilson came in after I had breakfasted, accompanied by the Attorney-general, Mr. W. O. Smith; and in conference it was agreed between us that Mrs. Clark could return home, and that Mrs. Wilson should remain as my attendant; that Mr. Wilson would be the person to inform the government of any request to be made by me, and that any business transactions might be made through him.

On the morning after my arrest all my retainers residing on my estates were arrested, and to the number of about forty persons were taken to the station-house, and then committed to jail. Amongst these was the agent and manager of my property, Mr. Joseph Heleluhe. As Mr. Charles B. Wilson had been at one time in a similar position, and was well acquainted with all my surroundings, and knew the people about me, it was but natural that he should be chosen by me for this office.

Mr. Heleluhe was taken by the government officers, stripped of all clothing, placed in a dark cell without light, food, air, or water, and was kept there for hours in hopes that the discomfort of his position would induce him to disclose something of my affairs. After this was found to be fruitless, he was imprisoned for about six weeks; when, finding their efforts in vain, his tormentors released him. No charge was ever brought against him in any way, which is true of about two hundred persons who were similarly confined.

On the very day I left the house, so I was informed by Mr. Wilson, Mr. A. F. Judd had gone to my private residence without search-warrant; and that all the papers in my desk, or in my safe, my diaries, the petitions I had received from my people, – all things of that nature which could be found were swept into a bag, and carried off by the chief justice in person. My husband’s private papers were also included in those taken from me.

To this day, the only document which has been returned to me is my will. Never since have I been able to find the private papers of my husband nor of mine that had been kept by me for use or reference, and which had no relation to political events. The most important historical note lost was in my diary. This was the record made by me at the time of my conversations with Minister Willis, and would be especially valuable now as confirming what I have stated of our first interview.

After Mr. Judd had left my house, it was turned over to the Portuguese military company under the command of Captain Good. These militiamen ransacked it again from garret to cellar. Not an article was left undisturbed. Before Mr. Judd had finished they had begun their work, and there was no trifle left unturned to see what might be hidden beneath. Every drawer of desk, table, or bureau was wrenched out, turned upside down, the contents pulled over on the floors, and left in confusion there. Some of my husband’s jewelry was taken; but this, in my application and offer to pay expenses, was afterwards restored to me.

Having overhauled the rooms without other result than the abstraction of many memorandums of no use to any other person besides myself, the men turned their attention to the cellar, in hopes possibly of unearthing an arsenal of firearms and munitions of war. Here they undermined the foundations to such a degree as to endanger the whole structure, but nothing rewarded their search. The place was then seized, and the government assumed possession; guards were placed on the premises, and no one was allowed to enter.

Imprisonment—Forced Abdication

For the first few days nothing occurred to disturb the quiet of my apartments save the tread of the sentry. On the fourth day I received a visit from Mr. Paul Neumann, who asked me if, in the event that it should be decided that all the principal parties to the revolt must pay for it with their lives, I was prepared to die? I replied to this in the affirmative, telling him I had no anxiety for myself, and felt no dread of death. He then told me that six others besides myself had been selected to be shot for treason, but that he would call again, and let me know further about our fate. I was in a state of nervous prostration, as I have said, at the time of the outbreak, and naturally the strain upon my mind had much aggravated my physical troubles; yet it was with much difficulty that I obtained permission to have visits from my own medical attendant.

About the 22d of January a paper was handed to me by Mr. Wilson, which, on examination, proved to be a purported act of abdication for me to sign. It had been drawn out for the men in power by their own lawyer, Mr. A. S. Hartwell, whom I had not seen until he came with others to see me sign it. The idea of abdicating never originated with me. I knew nothing at all about such a transaction until they sent to me, by the hands of Mr. Wilson, the insulting proposition written in abject terms. For myself, I would have chosen death rather than to have signed it; but it was represented to me that by my signing this paper all the persons who had been arrested, all my people now in trouble by reason of their love and loyalty towards me, would be immediately released. Think of my position, —sick, a lone woman in prison, scarcely knowing who was my friend, or who listened to my words only to betray me, without legal advice or friendly counsel, and the stream of blood ready to flow unless it was stayed by my pen.

My persecutors have stated, and at that time compelled me to state, that this paper was signed and acknowledged by me after consultation with my friends whose names appear at the foot of it as witnesses. Not the least opportunity was given to me to confer with any one; but for the purpose of making it appear to the outside world that I was under the guidance of others, friends who had known me well in better days were brought into the place of my imprisonment, and stood around to see a signature affixed by me.

When it was sent to me to read, it was only a rough draft. After I had examined it, Mr. Wilson called, and asked me if I were willing to sign it. I simply answered that I would see when the formal or official copy was shown me. On the morning of the 24th of January the official document was handed to me, Mr. Wilson making the remark, as he gave it, that he hoped I would not retract, that is, he hoped that I would sign the official copy.

Then the following individuals witnessed my subscription of the signature which was demanded of me: William G. Irwin, H. A. Widemann, Samuel Parker, S. Kalua Kookano, Charles B. Wilson, and Paul Neumann. The form of acknowledgment was taken by W. L. Stanley, Notary Public.

So far from the presence of these persons being evidence of a voluntary act on my part, was it not an assurance to me that they, too, knew that, unless I did the will of my jailers, what Mr. Neumann had threatened would be performed, and six prominent citizens immediately put to death. I so regarded it then, and I still believe that murder was the alternative. Be this as it may, it is certainly happier for me to reflect today that there is not a drop of the blood of my subjects, friends or foes, upon my soul.

When it came to the act of writing, I asked what would be the form of signature; to which I was told to sign, “Liliuokalani Dominis.” This sounding strange to me, I repeated the question, and was given the same reply. At this I wrote what they dictated without further demur, the more readily for the following reasons.

Before ascending the throne, for fourteen years, or since the date of my proclamation as heir apparent, my official title had been simply Liliuokalani. Thus I was proclaimed both Princess Royal and Queen. Thus it is recorded in the archives of the government to this day. The Provisional Government nor any other had enacted any change in my name. All my official acts, as well as my private letters, were issued over the signature of Liliuokalani. But when my jailers required me to sign “Liliuokalani Dominis,” I did as they commanded. Their motive in this as in other actions was plainly to humiliate me before my people and before the world. I saw in a moment, what they did not, that, even were I not complying under the most severe and exacting duress, by this demand they had overreached themselves. There is not, and never was, within the range of my knowledge, any such a person as Liliuokalani Dominis.

It is a rule of common law that the acts of any person deprived of civil rights have no force nor weight, either at law or in equity; and that was my situation. Although it was written in the document that it was my free act and deed, circumstances prove that it was not; it had been impressed upon me that only by its execution could the lives of those dear to me, those beloved by the people of Hawaii, be saved, and the shedding of blood be averted. I have never expected the revolutionists of 1887 and 1893 to willingly restore the rights notoriously taken by force or intimidation; but this act, obtained under duress, should have no weight with the authorities of the United States, to whom I appealed. But it may be asked, why did I not make some protest at the time, or at least shortly thereafter, when I found my friends sentenced to death and imprisonment? I did. There are those now living who have seen my written statement of all that I have recalled here. It was made in my own handwriting, on such paper as I could get, and sent outside of the prison walls and into the hands of those to whom I wished to state the circumstances under which that fraudulent act of abdication was procured from me. This I did for my own satisfaction at the time.

After those in my place of imprisonment had all affixed their signatures, they left, with the single exception of Mr. A. S. Hartwell. As he prepared to go, he came forward, shook me by the hand, and the tears streamed down his cheeks. This was a matter of great surprise to me. After this he left the room. If he had been engaged in a righteous and honorable action, why should he be affected? Was it the consciousness of a mean act which overcame him so? Mrs. Wilson, who stood behind my chair throughout the ceremony, made the remark that those were crocodile’s tears. I leave it to the reader to say what were his actual feelings in the case.

On January 17, 1893, Queen Lili‘uokalani made specific reference to the Constitution when she yielded her authority under threat of war to the President of the United States. Often referred to as the Lili‘uokalani assignment, the protest was carefully worded. Her protest stated:

On January 17, 1893, Queen Lili‘uokalani made specific reference to the Constitution when she yielded her authority under threat of war to the President of the United States. Often referred to as the Lili‘uokalani assignment, the protest was carefully worded. Her protest stated:

I, Lili‘uokalani, by the grace of God and under the constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Queen, do hereby solemnly protest against any and all acts done against myself and the constitutional Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom by certain persons claiming to have established a provisional government of and for this Kingdom.

That I yield to the superior force of the United States of America whose Minister Plenipotentiary, His Excellency John L. Stevens, has caused United States troops to be landed at Honolulu and declared that he would support the provisional government.

Now to avoid any collision of armed forces, and perhaps the loss of life, I do this under protest and impelled by said force yield my authority until such time as the Government of the United States shall, upon facts being presented to it, undo the action of its representatives and reinstate me in the authority which I claim as the Constitutional Sovereign of the Hawaiian Islands.

In all she makes three references to the Hawaiian Constitution:

The Queen was a limited Monarch whose powers were granted under the constitution of the Kingdom. At no point does she even imply that she was an absolute Monarch, but rather a constitutional Monarch that place her authority below and not above the Constitution. The yielding of authority was limited and confined to the circumstances of the situation the Hawaiian government was facing with the United States troops.

Since 1864, the Hawaiian Kingdom fully adopted the constitutional principle of separation of powers. This is a fundamental principle and serves as the cornerstone of constitutional governance. The separation of powers doctrine provides for a check and balance between three branches: the Legislative power, which is the power to enact laws; the Judicial power, which is the power to interpret laws; and the Executive power, which is the power to execute laws. The constitutional powers of the Hawaiian Executive are much more vast than the Judicial and Legislative powers and includes both police power, which is law enforcement, and administrative power, which is to maintain and administer governance through agencies established by law. The doctrine also provides for the separation and not the consolidation of power into one entity, which could become the source of tyranny. The separation of powers is outlined in Article 20 of the Constitution, “The Supreme Power of the Kingdom in its exercise is divided into the Executive, Legislative, and Judicial; these shall always be preserved distinct, and no Judge of a Court of Record shall ever be a member of the Legislative Assembly.”

Constitutional Powers of the Monarch

The powers and duties of the Monarch are outlined in Articles 26 through 43 of the Constitution. “To the King belongs the Executive power (Article 31).” The Constitution provides explicit powers to the Monarch but also limitations in the exercise of this power. “No act of the King shall have any effect unless it be countersigned by a Minister, who by that signature makes himself responsible (Article 42).” The Minister is accountable to the Legislative Assembly because the “Ministry hold seats ex officio, as Nobles, in the Legislative Assembly (Article 43).” Here follows the chief categories of the Monarch’s Executive powers created by the Constitution.

Chief Executive. The Constitution does not make direct provision for the vast administrative structure that the Monarch must oversee, but it does cite this capacity in Article 41 of the Constitution where the Privy Council of State shall assist the Monarch “in administering the Executive affairs of the Government.” In order to administer government, the Monarch has a Cabinet that consists “of the Minister of Foreign Affairs, the Minister of the Interior, the Minister of Finance, and the Attorney General of the Kingdom, and these shall be His Majesty’s Special Advisers in the Executive affairs of the Kingdom; and they shall be ex officio Members of His Majesty’s Privy Council of State.” Provisions for the administration of government is provided in the Civil Code.

Police Power. The Monarch’s role in law enforcement rests on the constitutional requirement that the “laws are obligatory are obligatory upon all persons, whether subjects of this kingdom, or citizens or subjects of any foreign State, while within the limits of this kingdom, except so far as exception is made by the laws of nations in respect to Ambassadors or others (§6, Civil Code).” The Monarch serves as chief executive of government with police power vested in the Marshall, whose duty is “to preserve the public peace of the Kingdom, to have the charge and supervision of all jails, prisons and houses of correction, and to safely keep all prisoners committed thereto; to execute all lawful precepts, and mandates directed to him by the King, or by any judge, court, minister or governor; to arrest fugitives from justice, as well as all criminals and other violators of the laws; and, generally, to perform all such other duties as may be imposed upon him by law (§260, Civil Code).” Should assistance be needed, the Monarch can invoke the authority of “commander in chief” and deploy the armed forces, including units of the Kingdom’s militia, to enforce the law.

The authority the Queen temporarily yielded to the President under threat of war on January 17, 1893, was not her full executive power, but only her police power that would be utilized to apprehend the insurgents in order “to avoid any collision of armed forces, and perhaps the loss of life.” She did not yield her administrative power that includes the following categories of Executive power.

Appointment and Removal Power. One of the most important administrative powers of the Monarch is to appoint people to fill high-level positions in the administration such as the Privy Council of State and the Cabinet Council. Articles 41 and 42 gives the Monarch the power to select top officials, who hold office during the pleasure of the Monarch. There is no limit to the appointment power, but government officials are responsible to the Legislative Assembly. “The Nobles shall be a Court, with full and sole authority to hear and determine all impeachments made by the Representatives, as the Grand Inquest of the Kingdom, against any officers of the Kingdom, for misconduct or maladministration in their offices, and “No Minister shall sit as a Noble on the trial of any impeachment (Article 59).” The Legislative Assembly could also exercise their right of a vote of no confidence.

Clemency. The Constitution gives the Monarch the “power to grant reprieves and pardons, after conviction, for all offenses, except in cases of impeachment (Article 27).” Clemency or pardons can only be granted after the individuals have been convicted and not before.

Between November 13 and December 18, 1893, the Queen was in negotiations with the United States Ambassador to Hawai‘i, Albert Willis. The negotiations centered on the findings of the investigation by President Cleveland that concluded the United States diplomat and troops were responsible for the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian government and committed to restore it. As a condition of the restoration, the Queen agreed to grant full pardons to the insurgents and their supporters. This was an executive agreement that came to be know as the Agreement of restoration.

Bills and Resolutions Passed by the Legislature. Under Article 31 of the Constitution, “All laws that have passed the Legislative Assembly, shall require His Majesty’s signature in order to their validity.” The Monarch’s signature must be “countersigned by a Minister, who by that signature makes himself responsible (Article 42).” But if the Monarch objects to the bills or resolutions, he “will return it to the Legislative Assembly, who shall enter the fact of such return on its journal, and such Bill or Resolution shall not be brought forward thereafter during the same session (Article 49).”

Legislative Proposals. The Constitution does not provide any provision for the Monarch to recommend legislation, but the Monarch does appoint Nobles to serve in the Legislative Assembly and his Cabinet Ministers are ex officio members of the Nobles as well. The power to recommend is inherent in the role the Monarch has when the Legislative Assembly is convened and the assembly is opened by a speech.

Budgeting. Article 44 of the Constitution gives the Monarch the power to recommend fiscal policies. “The Minister of Finance shall present to the Legislative Assembly in the name of the Government, on the first day of the meeting of the Legislature, the Financial Budget, in the Hawaiian and English languages.” The Legislature must past an appropriation bill based upon the report by the Minister of Finance. The power to control the budget process is one of the most important administrative prerogatives of the Monarch. It is the Monarch who decides where and how money should be spent.

In 1855, the Legislature was unable to pass an appropriation bill because of a disagreement of the House of Nobles and the House of Representatives, which at the time was a bicameral Legislature. The Minister of Finance estimated that the House of Representatives appropriation bill exceeded the revenues of the government by $200,000.00. This caused the Monarch to exercise the constitutional prerogative of dissolving the Legislature on June 16, 1855, and called for a new election of Representatives to meet with the House of Nobles in extraordinary session on July 30, 1855. The special session of the Legislature met for thirteen days and an appropriation bill was approved.

Power to Amend the Constitution. The power to amend or change the Constitution rests with the Legislative Assembly and the Monarch. Article 80 provides “Any amendment or amendments to this Constitution may be proposed in the Legislative Assembly, and if the same shall be agreed to by a majority of the members thereof, such proposed amendment or amendments shall be entered on its journal, with the yeas and nays taken thereon, and referred to the next Legislature; which proposed amendment or amendments shall be published for three months previous to the next election of Representatives; and if in the next Legislature such proposed amendment or amendments shall be agreed to by two-thirds of all the members of the Legislative Assembly, and be approved by the King, such amendment or amendments shall become part of the Constitution of this country.”

In 1887, under threat of assassination, King Kalakaua signed a new constitution for the country, which has come to be known as the “bayonet” constitution. This so-called constitution was in direct violation of Article 80, which made the 1864 Constitution along with the amendments still binding.

Emergency Powers. In times of crisis the Monarch can lay claim to extraordinary powers to preserve the Kingdom. Such emergency powers are granted expressly under Article 37 of the Constitution, “The King, in case of invasion or rebellion, can place the whole Kingdom or any part of it under martial law.”

Treaty Powers. Article 29 of the Constitution gives the Monarch “the power to make Treaties,” but “Treaties involving changes in the Tariff or in any law of the Kingdom shall be referred for approval to the Legislative Assembly.” So long as the treaty provides no change to any existing tariff or law of the Kingdom, the Monarch has full power to ratify with his signature and countersigned by a Minister.

Recognition and Appointment Powers. The Constitution explicitly grants the Monarch the power to appoint Public Ministers to serve diplomatic in a diplomatic capacity and to recognize foreign governments. Article 29 provides “The King appoints Public Ministers, who shall be commissioned, accredited, and instructed agreeably to the usage and law of Nations;” Article 30 provides “It is the King’s Prerogative to receive and acknowledge Public Ministers.” Because the acts of sending an ambassador to a country and receiving its representative imply recognition of the legitimacy of the foreign government involved, the Monarch has exclusive authority to decide which foreign governments will be recognized by the Hawaiian Kingdom.

Commander in Chief. Article 26 of the Constitution provides “The King is the Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy, and of all other Military Forces of the Kingdom, by sea and land; and has full power by Himself, or by any officer or officers He may appoint, to train and govern such forces, and He may judge best for the defense and safety of the Kingdom. The Constitution does not give the Monarch complete domination over the war-making function. The power to declare war is only with “the consent of the Legislative Assembly.”

Head of State and Head of Government. The Monarch is both Head of State and Head of Government. The Head of State serves as a symbol of the permanence of the national state, while the Head of Government administers governance. The Monarch’s role as Head of State includes the obligation to take the oath of office, deliver a message at the opening of the Legislative Assembly, and to receive ambassadors from other countries.

The hearings held by the U.S. Department of Interior throughout the Hawaiian Islands are attracting both Hawaiians and non-Hawaiians to give testimony—the sleeping giant has awakened. What is astonishing is the level of legal sophistication and historical accuracies displayed by those giving their testimony. Combined with emotions, these testimonies are eerily similar to the voices of Hawaiians documented in an article in the September 30, 1897 publication of the San Francisco Call newspaper.

This is a re-posting of a blog entry on January 29, 2014.

The article was published and authored by Miriam Michelson who was an American journalist and writer. It was written as Michelson was leaving Honolulu harbor on board the Steamship Australia heading to San Francisco. Michelson was sent to the Hawaiian Islands to do a story on annexation. Her story centers on a signature petition against annexation being gathered throughout the islands by the Hawaiian Patriotic League (Hui Aloha ‘Aina) and she bears witness to one of those meetings in the city of Hilo on the Island of Hawai‘i.

The article was published and authored by Miriam Michelson who was an American journalist and writer. It was written as Michelson was leaving Honolulu harbor on board the Steamship Australia heading to San Francisco. Michelson was sent to the Hawaiian Islands to do a story on annexation. Her story centers on a signature petition against annexation being gathered throughout the islands by the Hawaiian Patriotic League (Hui Aloha ‘Aina) and she bears witness to one of those meetings in the city of Hilo on the Island of Hawai‘i.

It is a powerful article that speaks to the issue of annexation from the Hawaiian perspective and the article’s title clearly speaks to the veracity of what the reader will read. Not known at the time, however, was whether or not the signature petitions would prevent the United States Senate from ratifying the so-called treaty of  annexation. Before the Senate convened in December of 1897, officers of the Hawaiian Patriotic League and the Hawaiian Political Association traveled to Washington, D.C. and met with Senator George Hoar of Massachusetts. Senator Hoar agreed to submit the signature petition onto the record of the Senate when it convened, and by March of 1898, the signature petition successfully killed the treaty as the Senate was unable to garner enough votes for ratification.

annexation. Before the Senate convened in December of 1897, officers of the Hawaiian Patriotic League and the Hawaiian Political Association traveled to Washington, D.C. and met with Senator George Hoar of Massachusetts. Senator Hoar agreed to submit the signature petition onto the record of the Senate when it convened, and by March of 1898, the signature petition successfully killed the treaty as the Senate was unable to garner enough votes for ratification.

Here follows a snippet of the article, which is quite lengthy, but you can read it in its entirety by going to this link and downloading the entire article in PDF format. “Strangling Hands Upon A Nations Throat”

*****************************************************

The strongest memory I have of the islands is connected with the hall of the Salvation Army at Hilo, on the Island of Hawaii. It’s a crude little place, which holds about 300 people, I should think. The rough, uncovered rafters show above, and the bare walls are relieved only by Scriptural admonitions in English and Hawaiian:

“Boast not thyself of to-morrow.” “Without Christ there is no salvation.”

As I entered, the bell on the foreign church, up on one of the beautiful Hilo hills, was striking ten. The place was packed with natives, and outside stood a patient crowd unable to enter. It was a women’s meeting, but there were many men present. The women were dressed in Mother Hubbards of calico or cloth and wore sailor hats—white or black. The men were in coats and trousers of American make.

Presently the crowd parted and two women walked in, both very tall, dressed in handsome free-flowing trained gowns of black crepe-braided in black. They wore black kid gloves and large hats of black straw with black feathers. The taller of the two—a very queen in dignity and repose—wore nodding red roses in her hat, and about her neck and falling to the waist a long, thick necklace of closely strung, deep-red, coral-like flowers, with delicate ferns interspersed.

This was Mrs. Kuaihelani Campbell, the president of the Women’s Hawaiian Patriotic League. Her companion was the secretary of the branch in Hilo.

It was almost pitiful to note the reception of these two leaders—the dumb, almost adoring fondness in the women’s eyes; the absorbed, close interest in the men’s dark heavy faces.

After the enthusiasm had subsided the minister of the Hawaiian church arose. He is tall, blonde, fair faced, three-quarters white, as they say here. Clasping his hands in front and looking down over the bowed dark heads before him he made the short opening prayer. He held himself well, his sentences were short and his manner was simple.

There is something wonderfully effective in earnest prayer delivered in an ancient language with which one is unfamiliar. One hears not words, but tones. His feelings, not his reason, are appealed to. Freed of the limiting effects of stereotyped phrases the imagination supplies the sense. Like the Hebrew and the Latin the Hawaiian tongue seems to touch the primitive sources of one’s nature, to strip away the complicated armor with which civilization and worldliness have clothed us and to leave the emotions bare for that wonderful instrument, a man’s deep voice, to play upon.

The minister closed and a deep murmuring “Amen” from the people followed.

I watched Mrs. Emma Nawahi curiously as she rose to address the people. I have never heard two women talk in public in quite the same way. Would this Hawaiian woman be embarrassed or timid, or self-conscious or assertive?

Not any of these. Her manner had the simple directness that made Charlotte Perkins Stetson, two years ago, the most interesting speaker of the Woman’s Congress. But Mrs. Stetson’s pose is the most artistic of poses—a pretense of simplicity. This Hawaiian woman’s thoughts were of her subject, not of herself. There was an interesting impersonality about her delivery that kept my eyes fastened upon her while the interpreter at my side whispered his translation in short, detached phrases, hesitating now and then for a word, sometimes completing the thought with a gesture.

“We are weak people, we Hawaiians, and have no power unless we stand together,” read Mrs. Nawahi, frequently raising her eyes from her paper and at times altogether forgetting it.

“We are weak people, we Hawaiians, and have no power unless we stand together,” read Mrs. Nawahi, frequently raising her eyes from her paper and at times altogether forgetting it.

“The United States is just—a land of liberty. The people there are the friends, the great friends of the weak. Let us tell them—let us show them that as they love their country and would suffer much before giving it up, so do we love our country, our Hawaii, and pray that they do not take it from us.”

“Our one hope is in standing firm—shoulder to shoulder, heart to heart. The voice of the people is the voice of God. Surely that great country across the ocean must hear our cry. By uniting our voices the sound will be carried on so they must hear us.”

“In this petition, which we offer for your signature to-day, you, women of Hawaii, have a chance to speak your mind. The men’s petition will be sent on by the men’s club as soon as the loyal men of Honolulu have signed it. There is nothing underhand, nothing deceitful in our way—our only way—of fighting. Everybody may see and may know of our petition. We have nothing to conceal. We have right on our side. This land is ours—our Hawaii. Say, shall we lose our nationality? Shall we be annexed to the United States? Aole loa. Aole loa.”

It didn’t require the interpreter’s word to make me understand the response. One could read negation, determination in every intent, dark face.

“Never!’ they say,” the man beside me muttered. “Never! they say. ‘No! No!’ they say-”

But the presiding officer, a woman, was introducing Mrs. Campbell to the people. Her large mouth parted in a pleased smile as the men and women stamped and shouted. She spoke only a few words, good-naturedly, hopefully. Once its seemed as though she were talking them all in her confidence, so sincere and soft was her voice as she leaned forward.

“Stand firm, my friends. Love of country means more to you and to me than anything else. Be brave; be strong. Have courage and patience. Our time will come. Sign this petition—those of you who love Hawaii. How many—how many will sign?”

“Stand firm, my friends. Love of country means more to you and to me than anything else. Be brave; be strong. Have courage and patience. Our time will come. Sign this petition—those of you who love Hawaii. How many—how many will sign?”

She held up a gloved hand as she spoke, and in a moment the palms of hundreds of hands were turned toward her.

They were eloquent, those deep lined, broad, dark hands, with their short fingers and worn nails. They told of poverty, of work, of contact with the soil they claim. The woman who presided had said a few words to the people, when all at once I saw a thousand curious eyes turned upon me.

“What is it?” I asked the interpreter. “What did she say?”

He laughed. “‘A reporter is here,’ she says. She says to the people, ‘Tell how you feel. Then the Americans will know. Then they may listen.’”

A remarkable scene followed. One by one men and women rose and in a sentence or two in the rolling, broad voweled Hawaiian made a fervent profession of faith.

“My feeling,” declared a tall, broad-shouldered man, whose dark eyes were alight with enthusiasm. “This is my feeling: I love my country and I want to be independent—now and forever.”

“And my feeling is the same,” cried a stout, bold-faced woman, rising in the middle of the hall. “I love this land. I don’t want to be annexed.”

“This birthplace of mine I love as the American loves his. Would he wish to be annexed to another, greater land?”

“I am strongly opposed to annexation. How dare the people of the United States rob a people of their independence?”

“I want the American Government to do justice. America helped to dethrone Liliuokalani. She must be restored. Never shall we consent to annexation!”

“My father is American; my mother is pure Hawaiian. It is my mother’s land I love. The American nation has been unjust. How could we ever love America?”

“Let them see their injustice and restore the monarchy!” cried an old, old woman, whose dark face framed in its white hair was working pathetically.

“If the great nations would be fair they would not take away our country. Never will I consent to annexation!”

“Tell America I don’t want annexation. I want my Queen,” said the gentle voice of a woman.

“That speaker is such a good woman,” murmured the interpreter. “A good Christian, honest, kind and charitable.”

“I’m against annexation—myself and all my family.”

“I speak for those behind me,” shouted a voice from far in the rear. “They cannot come in—they cannot speak. They tell me to say, ‘No annexation. Never.’”

I am Kauhi of Kalaoa. We call it Middle Hilo. Our club has 300 members. They have sent me here. We are all opposed to annexation—all—all!”

He was a young man. His open coat showed his loose dark shirt; his muscular body swayed with excitement. He wore boots that came above his knees. There was a large white handkerchief knotted about his brown throat, and his fine head, with its intelligent eyes, rose from his shoulders with a grace that would have been deerlike were it not for its splendid strength.

“I love my country and oppose annexation,” said a heavy-set, gray-haired man with a good, clear profile. “We look to America as our friend. Let her not be our enemy!”

“Hekipi, a delegate from Molokai to the league, writes: ‘I honestly assert that the great majority of Hawaiians on Molokai are opposed to annexation. They fear that if they become annexed to the United States they will lose their lands. The foreigners will reap all the benefit and the Hawaiians will be placed in a worse position than they are to-day.”

“I am a mail carrier. Come with me to my district.” A man who was sitting in the first row rose and stretched out an appealing hand. “Come to my district. I will show you 2000 Hawaiians against annexation.”

“I stand—we all stand to testify to our love of our country. No flag but the Hawaiian flag. Never the American!”

There was cheering at this, and the heavy, sober, brown faces were all aglow with excited interest.

I sat and watched and listened.

At Honolulu I had asked a prominent white man to give me some idea of the native Hawaiian’s character.

“They won’t resent anything,” he said, contemptuously. “They haven’t a grain of ambition. They can’t feel even envy. They care for nothing but easy and extremely simple living. They have no perseverance, no backbone. They’re unfit.”

Yet surely here was no evidence of apathy, of stupid forbearance, of characterless cringing.

These men and women rose quickly one after another, one interrupting the other at times, and then standing expectantly waiting his turn—too simple, too sincere, it seemed to me, to feel self-conscious or to study for a moment about the manner of his speech, so vital was the matter delivered.

They stood as all other Hawaiians stand—with straight shoulders splendidly thrown back and head proudly poised. Some held their roughened, patient hands clasped, some bent and looked toward me, as though I were a sort of magical human telephone and phonograph combined.

I might misunderstand a word or two of the interpreted message, but there was no mistaking those earnest, brown faces and beseeched dark eyes, which seemed to try to bridge the distance my ignorance of their language and their slight acquaintance with mine created between us.

I verily believe that even the most virulent of annexationists would have thought these Hawaiians human; almost worthy of consideration.

The people rose now and sang the majestic Hawaiian National Hymn. It was sung fervently, a full, deep chorus of hundreds of voices. The music is beautifully characteristic, with its strong, deep bass chords to which the women’s plaintive, uncultivated voices answer. Then there was a benediction, and the people passed out into the muddy street.

To listen to the interview click here.

The Star Advertiser reports “Interior Department meetings draw testimony opposed to recognition of a future native nation“

The vast majority of people who testified before a federal panel Monday soundly rejected any attempt by the Obama administration to pursue federal recognition of a future Native Hawaiian governing body.

The vast majority of people who testified before a federal panel Monday soundly rejected any attempt by the Obama administration to pursue federal recognition of a future Native Hawaiian governing body.

In often passionate, sometimes heated testimony, dozens of speakers said they opposed any effort by the Department of the Interior to start a rule-making process that could set the framework for re-establishing a government-to-government relationship with Native Hawaiians.

At the first two of 15 public meetings scheduled over the next two weeks, most of those testifying said the department does not have the authority to re-establish that relationship and implored the agency to halt the process and not interfere in Hawaiians’ right to political self-determination.

“We don’t need you folks to come in and tell us what to do,” Hawaiian activist Dennis “Bumpy” Kanahele told the panel Wednesday morning at the state Capitol auditorium.

He expanded on those remarks at an evening meeting in Waimanalo, where 154 people signed up to speak.

“You gotta realize that a crime has taken place,” Kanahele said. “And the United States essentially came back to the crime scene. We need to decide how to govern ourselves. We don’t need the federal government.”

At the evening session he was followed by Brandon Maka‘awa‘awa of Waimanalo.

“In the past the Native Hawaiian people have suffered the manipulation of our rights to self-determination on numerous occasions,” he said. “Once again our inherent sovereignty and rights to self-determination are being undermined by these DOI meetings. It is our political right to govern ourselves. The Native Hawaiian people have already begun the process and should be allowed to finish it without the interference of the U.S. government.”

Many of the speakers said they are not interested in seeing Hawaiians attain a tribal status similar to American Indians, which was what backers of the so-called Akaka Bill in Congress unsuccessfully attempted to do for more than a decade.

They said Hawaii is an illegally occupied sovereign nation and that any government-to-government dealings should be between a kingdom government and the U.S. secretary of state, who deals with foreign nations on behalf of the United States, not the interior secretary.

DeMont R.D. Conner of Nanakuli used the analogy of a car theft and the federal government’s 1993 apology for the 1893 overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy to question the department’s current actions: The thief apologizes to the owner but keeps the car.

“Go back and tell your boss, ‘Give ’em back the car!'” Conner told the panel.

More than 140 people signed up to testify at the Monday morning session, which was attended by an overflow crowd of more than 200 people and lasted more than three hours.

“It’s very simple: You don’t have jurisdiction here,” said testifier Remi Abellira, adding, “We don’t need recognition. We know who we are.”

Over the next two months, the department is taking public comments at the Hawaii sessions and at additional meetings in Native American communities on the mainland. It also is soliciting written comments.

The feedback is meant to help the Obama administration determine whether it should propose a federal rule that would facilitate the process for re-establishing a government-to-government relationship.

It also is soliciting comments to determine what form that process should take — if the administration decides to pursue that path — and whether the federal government should assist the Native Hawaiian community in reorganizing its government.

“Be clear. This is only a first step,” Rhea Suh, the Interior Department’s assistant secretary for policy, management and budget, told those at the morning session.

Suh was one of six officials from that agency and the Justice Department to sit on the panel.

Sam Hirsch, a Justice Department attorney, told the crowd that the federal government does not have procedures in place to pursue administrative recognition of a Native Hawaiian government.

That’s why the meetings are needed should the Interior Department decide to pursue that path, Hirsch said.

But he emphasized that the sessions will not address what structure the yet-to-be-formed Hawaiian government should take.

“That’s a matter for the community” to decide, Hirsch said.

To the main questions asked by the panel, University of Hawaii law professor Williamson Chang offered these comments: “I want to say no, no, no. No to federal recognition, no to occupation, no to the United States.”

Walter Ritte of Molokai testified that the department’s timing couldn’t be worse, particularly as Hawaiians are engaged in a controversial nation-building effort.

“You’re bringing confusion,” he said.

Of the several dozen who testified at the morning session, only a few supported the department’s plan.

Office of Hawaiian Affairs Chairwoman Collette Machado was among those, and her time at the microphone eventually turned into a shouting match with members of the audience.

Davianna Pomaikai McGregor, a UH ethnic studies professor, also offered supporting testimony, saying the process should not interfere with the re-establishment of the kingdom government.

“We should be supporting both efforts,” McGregor told the Honolulu Star-Advertiser after she testified.

Other than occasional jeers from the audience and a few profanity-laced comments, most of the morning session was civil. Some participants came decked in traditional garb or carrying signs, such as “What Tribe Has a Palace.”

Several expressed frustration that the federal government has solicited similar feedback about recognition over the years, yet nothing came of it.

“It’s the same old garbage,” one speaker said.

https://vimeo.com/99015206

Another series in The Sovereignty Conversations titled Na Maka Hosted by Lela Hubbard and Juanita Brown Kawamoto. In this Episode we have a re-cap with Juanita and Professor Williamson Chang of the University of Hawai‘i Richardson School of Law on the United States Department of the Interior’s Native Hawaiian Recognition hearings held at the Hawaii State Capitol on June 23, 2014.

https://vimeo.com/98727591

A conversation with Dr. Ron Williams, Jr. on the Claiming of Christianity in the Hawaiian Kingdom. A provocative look at the Christian Hawaiians and the churches during the times of the Provisional Government. Williams got his Ph.D. in History from the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa.

https://vimeo.com/98826630

A conversation with Dr. Umi Perkins on privatizing land in Hawai‘i. Perkins has a Ph.D. in Political Science from the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa.

https://vimeo.com/98797509

A conversation with Donovan Preza on the genealogy of Hawaiian territoriality. The interweaving between contemporary issues of Hawaiian Sovereignty and Real property. Preza is a Ph.D. student in Geography at the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa.

The only way that the Department of Interior can have authority to hold hearings in the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom, being a foreign State, is to first show that the Department of Justice, through its Office of Legal Counsel, has answered Dr. Crabbe’s question “Does the Hawaiian Kingdom, as a sovereign independent State, continue to exist as a subject of international law?” in the negative. Until then, the Department of Interior is violating the basic principle of international law, whereby governments have the obligation and duty to not intervene in the internal affairs of another sovereign independent State, which is precisely what the United States did in 1893.

There is a common misunderstanding that the United States federal government can enter the territory of other countries unfettered. Governments, which are the physical machineries of sovereign States, have omnipotent authority within their own territorial limits, and range from constitutional governments to totalitarian regimes. But when governments deal with other foreign countries their actions are regulated by international law, which includes treaties (agreements) and customary international law.

The United States federal government was established in 1789 with three branches of government called the Executive (President), Legislative (Congress) and Judicial (Supreme Court) branches. Of the three branches, the President alone is responsible for the enforcement of the laws that Congress has enacted as well as international laws that bind the United States abroad. To carry out this duty, the President has departments and agencies, which serve as the administrative arm of the Presidency.

In 1789 there were only three departments under the President: the Department of Foreign Affairs, which later in the same year was changed to the Department of State; the Department of the Treasury; and the Department of War, which was later changed to the Department of Defense in 1949. Today there exists twelve additional departments: Department of Justice (est. 1870), Department of Agriculture (est. 1862), Department of Commerce (est. 1903), Department of Labor (est. 1913), Department of Health and Human Services (est. 1953), Department of Housing and Urban Development (est. 1965), Department of Transportation (est. 1966), Department of Energy (est. 1977), Department of Education (est. 1980), Department of Veteran Affairs (est. 1989), Department of Homeland Security (est. 2002), and the Department of Interior (est. 1849).

Each department has a specific role and function under the President’s authority and duty to enforce the law. Only the President represents the United States in foreign affairs—neither the Congress nor the Supreme Court has that authority. According to the United States Supreme Court, U.S. v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp. (1935), there exists the “plenary and exclusive power of the President as the sole organ of the federal government in the field of international relations—a power which does not require as a basis for its exercise an act of Congress.” To carry out this function, the President has the Department of State and the Department of Defense. All other departments are limited in authority to the territory and jurisdiction of the United States.

The Department of State is “responsible for international relations of the United States, equivalent to the foreign ministry of other countries,” through diplomats that include Ambassadors and Consuls. The Department of Defense is responsible for “coordinating and supervising all agencies and functions of the government concerned directly with national security and the United States Armed Forces.” Within the Executive branch, the Department of State is the lead advisor to the President on foreign policies, and the Department of Defense carries out these foreign policies if international law authorizes it, e.g. war or status of forces agreements.

As a foreign State, the Hawaiian Kingdom has dealt with the Department of State and the Department of Defense, but has never dealt with any of the other Departments because the Hawaiian Kingdom was never part of the United States, especially the Department of Interior. The Department of Interior is responsible for the domestic affairs of the United States that included “the construction of the national capital’s water system, the colonization of freed slaves in Haiti, exploration of western wilderness, oversight of the District of Columbia jail, regulation of territorial governments, management of hospitals and universities, management of public parks, and the basic responsibilities for Indians, public lands, patents, and pensions,” which now includes Native Hawaiians.

With the recent attention surrounding the Department of the Interior’s public meetings throughout the Islands, focus is now on centering on “authority” and not “policies.” This is attributed to the education of the masses as to the legal and political history of Hawai‘i, which has drawn attention to the Office of Hawaiian Affairs CEO Dr. Kamana‘opono Crabbe’s letter to the Secretary of State John Kerry requesting clarity as to the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent and sovereign State under international law. Under the international law principle presumption of continuity, since the Hawaiian Kingdom was an independent State, which the Department of Interior and the Department of Justice admit in their joint report in 2000, international law provides that an established State is presumed to still exist until proven extinguished under international law.

According to Professor Crawford, The Creation of States in International Law (2006), p. 34, who is not only the leading authority on States, but was also the presiding arbitrator in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, “There is a strong presumption that the State continues to exist, with its rights and obligations, despite revolutionary changes in government, or despite a period in which there is no, or no effective, government. Belligerent occupation does not affect the continuity of the State, even where there exists no government claiming to represent the occupied State.” So despite the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government by the United States on January 17, 1893, and the prolonged occupation since the Spanish-American War in 1898, the Hawaiian Kingdom, as a State, would continue to exist even if there was no Hawaiian government. The presumption of continuity places the burden on the United States to show under international law, and not United States law, that the Hawaiian Kingdom does not continue to exist. A congressional joint resolution of annexation is not evidence that the Hawaiian Kingdom ceases to exist an independent State under international law, but rather is the evidence of the violation of international law and Hawaiian sovereignty.

In like fashion to the Department of Interior’s public meetings, a Congressional committee called the Hawaiian Commission for the creation of a territorial government was holding public meetings in Honolulu from August through September 1898. The Commission was headed by Senator Morgan and established on July 9, 1898 after President McKinley signed the joint resolution of annexation on July 7, 1898. The Hawaiian Patriotic League who was responsible for securing 21,269 signatures against annexation submitted a memorial, which was also printed in two Honolulu newspapers, one in the Hawaiian language and the other in English. The memorial stated:

WHEREAS: By memorial the people of Hawai‘i have protested against the consummation of an invasion of their political rights, and have fervently appealed to the President, the Congress and the People of the United States, to refrain from further participation in the wrongful annexation of Hawai‘i; and

WHEREAS: The Declaration of American Independence expresses that Governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed:

THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED: That the representatives of a large and influential body of native Hawaiians, we solemnly pray that the constitutional government of the 16th day of January, A.D. 1893, be restored, under the protection of the United States of America.

The memorial is still relevant today and relies on the executive agreement entered into between President Cleveland and Queen Lili‘uokalani in 1893 that bound the President and his successors in office to restore the Hawaiian Kingdom government as it stood before the invasion of United States troops on January 16, 1893, and thereafter the Queen or her successors in office would grant amnesty to the insurgents and their supporters. This Agreement of Restoration is a treaty under international law and remains binding on the office of the President today.

“If they can get you asking the wrong questions, they don’t have to worry about answers.” – Thomas Pynchon, Gravity’s Rainbow

The U.S. Department of Interior (DOI) will be in the Hawaiian Kingdom holding public meetings throughout the Islands from June 23 to August 8, 2014 to get responses from the Native Hawaiian community to consider reestablishing a government-to-government relationship between the United States and the Native Hawaiian community. Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell who visited the country last year heads the DOI.

The U.S. Department of Interior (DOI) will be in the Hawaiian Kingdom holding public meetings throughout the Islands from June 23 to August 8, 2014 to get responses from the Native Hawaiian community to consider reestablishing a government-to-government relationship between the United States and the Native Hawaiian community. Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell who visited the country last year heads the DOI.

In a press release of June 18, 2014, the DOI stated, “The purpose of such a relationship would be to more effectively implement the special political and trust relationship that currently exists between the Federal government and the Native Hawaiian community. Today’s action, known as an Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPRM), provides for an extensive series of public meetings and consultations in Hawaii and Indian Country to solicit comments that could help determine whether the Department develops a formal, administrative procedure for reestablishing an official government-to-government relationship with the Native Hawaiian community and if so, what that procedure should be.”

“When I met with members of the Native Hawaiian community last year during my visit to the state, I learned first-hand about Hawaii’s unique history and the importance of the special trust relationship that exists between the Federal government and the Native Hawaiian community,” said Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell. “Through this step, the Department is responding to requests from not only the Native Hawaiian community but also state and local leaders and interested parties who recognize that we need to begin a conversation of diverse voices to help determine the best path forward for honoring the trust relationship that Congress has created specifically to benefit Native Hawaiians.”

At the center of the public meetings are five “threshold questions” for the community to respond to:

The DOI stated, “Over many decades, Congress has enacted more than 150 statutes that specifically recognize and implement this trust relationship with the Native Hawaiian community, including the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act, the Native Hawaiian Education Act, and the Native Hawaiian Health Care Act. The Native Hawaiian community, however, has not had a formal governing entity since the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii in 1893. In 1993, Congress enacted the Apology Resolution which offered an apology to Native Hawaiians on behalf of the United States for its role in the overthrow and committed the U.S. government to a process of reconciliation. In 2000, the Department of the Interior and the Department of Justice jointly issued a report on the reconciliation process that identified self-determination for Native Hawaiians under Federal law as their leading recommendation.”

A careful review of the joint report by the DOI and the Department of Justice, the report acknowledges that the Hawaiian Kingdom was a recognized sovereign and independent State. “The United States clearly viewed the Kingdom of Hawai‘i as an independent nation as evidenced by the negotiation and signing of several treaties (p. 22).” The report also acknowledges President Cleveland’s withdrawal of the first treaty of annexation entered into with the so-called provisional government and President Harrison’s administration; the subsequent investigation, which concluded the provisional government was self-proclaimed and that the United States was responsible for the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian government; and the executive agreement between the Queen and the President whereby the U.S. would restore the government and the Queen to grant amnesty. “President Cleveland did not desire, nor did he have the support of Congress, to engage United States military forces to declare war against the American citizens who controlled the Provisional Government (p. 28).” This was an act of non-compliance to the agreement of restoration, which allowed the insurgents to maintain unlawful control.

The report also acknowledges the failure of the second treaty of annexation entered into between the insurgency, calling themselves the Republic of Hawai‘i, and President McKinley, which resulted in Congress passing a joint resolution instead. The reported stated:

“With the election of President McKinley in 1896, the pro-annexation forces gained strength. The Republic of Hawai‘i continued to push for annexation although many Native Hawaiians were opposed. In September 1897, the “Petition against the Annexation of Hawaii Submitted to the U.S. Senate in 1897 by the Hawaiian Patriotic League of the Hawaiian Islands”, expressed the views of Native Hawaiians. The petition, signed by 21,169 people (more than half of the Native Hawaiian population) from Kaua‘i, Maui, Hawai‘i, Moloka‘i, O‘ahu, Lana‘i, and Kaho‘olawe provides evidence that Native Hawaiians were against annexation and wanted independence under a Monarchy (p. 29).”

…

“Consistent with the wishes expressed by Native Hawaiians, the Treaty of Annexation failed to pass the United States Senate by a two-thirds majority vote. However, by 1898, with the outbreak of the Spanish-American War in both the Pacific and Caribbean, the Newlands Joint Resolution of Annexation (Annexation Resolution) was offered by the pro-annexation forces and passed by a simple majority of the United States Senate and House of Representatives, thus becoming the instrument used to effect the annexation of the Republic of Hawai‘i. The constitutionality of the use of a Joint Resolution in lieu of a Treaty to annex Hawai‘i was a contentious issue at the time (p. 30).”

From this point the report continues a narrative of historical events to the present day that “assumes” the joint resolution of annexation extinguished the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent and sovereign State. To support this erroneous position, the report restates a section of the 1993 Apology resolution, “Whereas the Newlands [Annexation] Resolution effected the transaction between the Republic of Hawai‘i and the United States Government (p. 30).” This resolution is problematic on two points: first, as an act of Congress the resolution has no effect beyond United States territory; and, second, the Republic of Hawai‘i was not a government, but self-declared, which the Apology resolution admitted.

What the report conveniently omits is the conclusion of the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel opinion on the “Newlands [Annexation] Resolution” in its 1988 Opinion “Legal Issues Raised by Proposed Presidential Proclamation To Extend the Territorial Sea.” Douglas Kmiec, Acting Assistant Attorney General, authored the memorandum for Abraham D. Sofaer, legal advisor to the U.S. State Department. The Opinion states that the “clearest source of constitutional power to acquire territory is the treaty making power (p. 247).” When it came to Hawai‘i, however, Kmiec had a difficult time explaining how the Congress could acquire territory by a joint resolution. Kmiec referenced a U.S. constitutional scholar, Professor Willoughby, who stated:

“The constitutionality of the annexation of Hawaii, by a simple legislative act, was strenuously contested at the time both in Congress and by the press. The right to annex by treaty was not denied, but is was denied that this might be done by a simple legislative act… Only by means of treaties, it was asserted, can the relations between States be governed, for a legislative act is necessarily without extraterritorial force—confined in its operation to the territory of the State by whose legislature it is enacted (p. 252).”

After covering the limitation of Congressional authority and the objections made by members of the Congress, Kmiec concluded, “It is therefore unclear which constitutional power Congress exercised when it acquired Hawaii by joint resolution. Accordingly, it is doubtful that the acquisition of Hawaii can serve as an appropriate precedent for a congressional assertion of sovereignty over an extended territorial sea (p. 252).” There has been no followup opinion from the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel since 1988 that qualified how Congressional legislation could annex foreign territory. If the Department of Justice was unclear as to which constitutional power Congress exercised in 1898 when it purported to have annexed Hawaiian territory by joint resolution, it should still be unclear as to how Congress “has enacted more than 150 statutes that specifically recognize and implement this trust relationship with the Native Hawaiian community, including the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act, the Native Hawaiian Education Act, and the Native Hawaiian Health Care Act” stated in its press release.

It is clear that the Department of Justice had this information since 1988, but for obvious reasons did not cite that opinion in its joint report with the DOI that covered the portion on annexation (p. 26-30). To do so, would have completely undermined all the statutes the Congress has enacted for Hawai‘i, which would also include the lawful authority of the State of Hawai‘i government itself since it was created by an Act of Congress in 1959.

This was precisely the significance of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs CEO Dr. Kamana‘opono Crabbe’s questions to Secretary of State John Kerry. Without any evidence that the United States extinguished the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent and sovereign State under international law, the Hawaiian Kingdom is presumed to still be in existence and therefore under an illegal and prolonged occupation.

So before the “five threshold questions that will be the subject of the forthcoming public meetings regarding whether the Federal Government should reestablish a government-to-government relationship with the Native Hawaiian community” can be answered by the community, the only question that should be posed to the DOI at the public meetings is:

“Since the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel did not respond with evidence to the Office of Hawaiian Affairs CEO Dr. Kamana‘opono’s questions dated May 5, 2014 that the Hawaiian Kingdom does not exist as an independent and sovereign State under international law, I have to presume the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist. Therefore, my question to you is by what authority is the Department of Interior claiming to be here in Hawai‘i, being a foreign sovereign and independent State, since the Department of Justice has already concluded that Congress could not have annexed the Hawaiian Islands by a joint resolution?”