There are some today who mistakenly believe that if they can show a family genealogy that traces back to a Hawaiian ali‘i (nobility) they can lay claim to the throne. If this were true than anyone can lay claim. But it is not true because the Hawaiian Kingdom is a constitutional monarchy that provides rules and protocol.

The first rule is that under Hawaiian law titles of nobility are not inheritable. However, in Europe titles of nobility are inheritable, which traces back to the Middle Ages. This is a feudal rule that developed when the nobility were able to inherit their lands and consequently their titles were also inheritable within the family. The Hawaiian Kingdom did not rise from the Middle Ages. It is Polynesian. According to Article 35 of the 1864 Hawaiian Constitution “All Titles of Honor, Orders, and other distinctions, emanate from the King.”

Three Estates of the Hawaiian Kingdom

The government of the Hawaiian Kingdom is a constitutional and limited monarchy comprised of three Estates: the Monarch, Nobles and the People. An Estate is defined as a “political class.” All three political classes work in concert and provides for the legal basis of the government and its authority. Article 45 of the 1864 Hawaiian constitution, provides: “The Legislative power of the Three Estates of this Kingdom is vested in the King, and the Legislative Assembly; which Assembly shall consist of the Nobles appointed by the King, and of the Representatives of the People, sitting together.”

This provision is further elaborated under §768, Hawaiian Civil Code (Compiled Laws, 1884), “The Legislative Department of this Kingdom is composed of the King, the House of Nobles, and the House of Representatives, each of whom has a negative on the other, and in whom is vested full power to make all manner of wholesome laws, as they shall judge for the welfare of the nation, and for the necessary support and defense of good government, provided the same is not repugnant or contrary to the Constitution.” As each Estate has a negative on each other, no law can be passed without all three Estates agreeing.

According to Hawaiian law “No person shall ever sit upon the Throne, who has been convicted of any infamous crime, or who is insane, or an idiot (Article 25, 1864 Constitution),” which, by extension, extends to the Nobles whereby “The King appoints the members of the House of Nobles, who hold their seats during life, unless in case of resignation, subject, however, to punishment for disorderly behavior. The number of members of the House of Nobles shall not exceed thirty (§771, Compiled Laws).”

Representatives of the People shall be Hawaiian subjects or denizens “who shall have arrived at the full age of twenty-five years, who shall know how to read and write; who shall understand accounts, and who shall have resided in the Kingdom for at least one year immediately preceding his election; provided always, that no person who is insane, or an idiot, or who shall at any time have been convicted of theft, bribery, perjury, forgery, embezzlement, polygamy, or other high crime or misdemeanor, shall ever hold seat as Representative of the people (§778, Compiled Laws).”

The number of the Representatives of the people in the Legislature shall be twenty-eight: eight for the Island of Hawai‘i (one for the district of North Kona, one for the district of South Kona, One for the district of Ka‘u, one for the district Puna, two for the district of Hilo, one for the district Hamakua, one for the district of Kohala); seven for the Island of Maui (two for the districts of Lahaina, Olowalu, Ukumehame, and Kaho‘olawe, one for the districts of Kahakuloa and Ka‘anapali, one for the districts of Waihe‘e and Honuaula, one for the districts of Kahikinui and Ko‘olau, one for the districts of Hamakualoa and Kula); two for the Islands of Molokai and Lanai; eight for the Island of O‘ahu (four for the districts of Honolulu that extends from Maunalua to Moanalua, one for the districts of Ewa and Waianae, one for the district of Waialua, one for the district of Ko‘olauloa, and one for the district of Ko‘olaupoko); and three for the island of Kaua‘i (one for the districts of Waimea, Nualolo, Hanapepe and the Island of Ni‘ihau, one for the districts of Puna, Wahiawa and Wailua, and one for the districts of Hanalei, Kapa‘a and ‘Awa‘awapuhi) (§780, Compiled Laws).

Electors of the Representatives shall be Hawaiian subjects or denizens “who shall have paid his taxes, who shall have attained the age of twenty years, and shall have been domiciled in the Kingdom for one year immediately preceding the election, and shall know how to read and write, if born since the year 1840, and shall have caused his name to be entered on the list of voters of his district…shall be entitled to one vote for Representative or Representatives of that district; provided, however, that no insane or idiotic person, or any person who shall have been convicted of any infamous crime within this Kingdom unless he shall have been pardoned by the King, and by the terms, and by the terms of such pardon have been restored to all the rights of a subject, shall be allowed to vote (p. 222, Compiled Laws).”

The Estate of the Crown

The first constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom was promulgated in 1840 by King Kamehameha III, which was superseded by the 1852 Constitution. Article 25 of the 1852 Constitution provided: “The crown is hereby permanently confirmed to His Majesty Kamehameha III. during his life, and to his successor. The successor shall be the person whom the King and the House of Nobles shall appoint and publicly

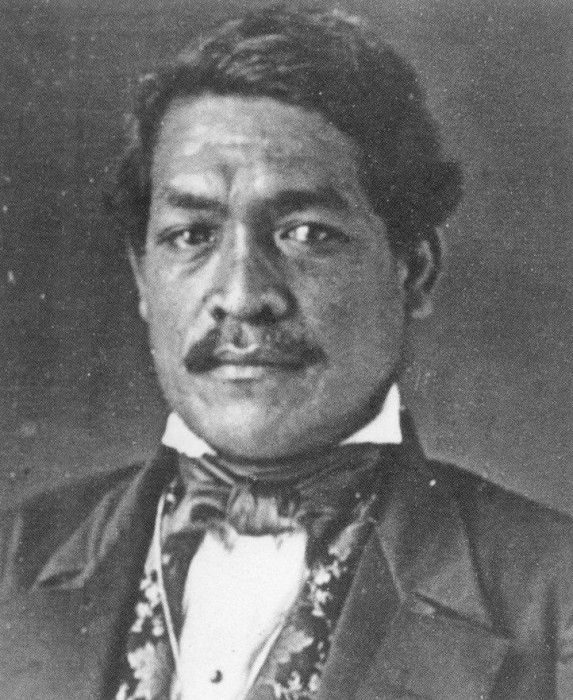

The first constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom was promulgated in 1840 by King Kamehameha III, which was superseded by the 1852 Constitution. Article 25 of the 1852 Constitution provided: “The crown is hereby permanently confirmed to His Majesty Kamehameha III. during his life, and to his successor. The successor shall be the person whom the King and the House of Nobles shall appoint and publicly  proclaim as such, during the King’s life; but should there be no such appointment and proclamation, then the successor shall be chosen by the House of Nobles and the House of Representatives in joint ballot.” Kamehameha III proclaimed his adopted son, Alexander Liholiho, to be his heir apparent after receiving confirmation from the Nobles in 1853. Alexander ascended to the Throne upon the death of King Kamehameha III on December 15, 1854.

proclaim as such, during the King’s life; but should there be no such appointment and proclamation, then the successor shall be chosen by the House of Nobles and the House of Representatives in joint ballot.” Kamehameha III proclaimed his adopted son, Alexander Liholiho, to be his heir apparent after receiving confirmation from the Nobles in 1853. Alexander ascended to the Throne upon the death of King Kamehameha III on December 15, 1854.

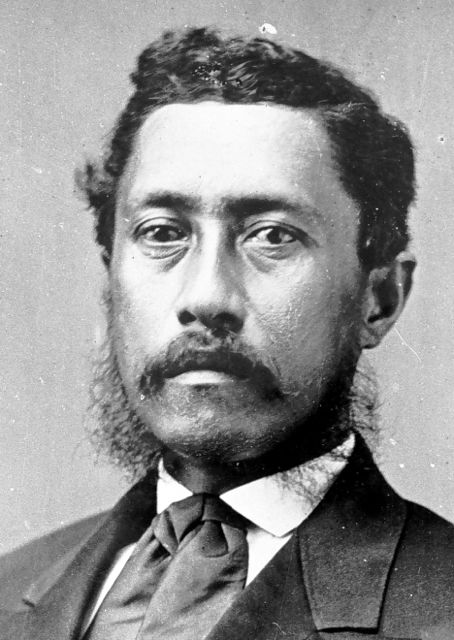

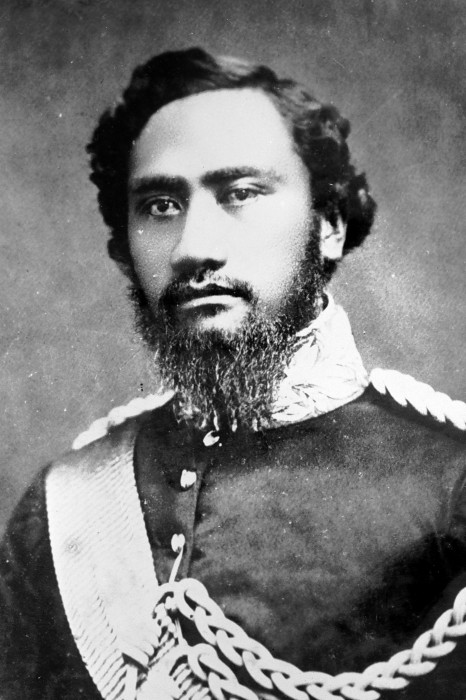

King Kamehameha V ascended to the Throne through the process of appointment by the Premier (Kuhina Nui) Victoria Kamamalu, and confirmation by the Nobles in 1863, because Kamehameha IV had no surviving children. His son and heir, Prince Albert Kamehameha, died at the age of four

King Kamehameha V ascended to the Throne through the process of appointment by the Premier (Kuhina Nui) Victoria Kamamalu, and confirmation by the Nobles in 1863, because Kamehameha IV had no surviving children. His son and heir, Prince Albert Kamehameha, died at the age of four  on August 27, 1862. Since the young Prince’s death, Kamehameha IV did not appoint a successor before he died on November 30, 1863. According to the 1852 Constitution, Article 47 provided, “Whenever the throne shall become vacant by reason of the King’s death…the Kuhina Nui, for the time being, shall…perform all the duties incumbent on the King, and shall have and exercise all the powers, which by this Constitution are vested in the King.”

on August 27, 1862. Since the young Prince’s death, Kamehameha IV did not appoint a successor before he died on November 30, 1863. According to the 1852 Constitution, Article 47 provided, “Whenever the throne shall become vacant by reason of the King’s death…the Kuhina Nui, for the time being, shall…perform all the duties incumbent on the King, and shall have and exercise all the powers, which by this Constitution are vested in the King.”

In 1864, a new constitution was promulgated by King Kamehameha V, and Article 22 of the 1864 Constitution provides that, “The Crown is hereby permanently confirmed to His Majesty Kamehameha V. and to the Heirs of His body lawfully begotten, and to their lawful Descendants in a direct line; failing whom, the Crown shall descend to Her Royal Highness the Princess Victoria Kamamalu Kaahumanu, and the heirs of her body, lawfully begotten, and their lawful descendants in a direct line. The Succession shall be to the senior male child, and to the heirs of his body; failing a male child, the succession shall be to the senior female child, and to the heirs of her body.” Princess Kamamalu died on May 29, 1866 without any lineal descendants, leaving the successors to the Throne solely with King Kamehameha V.

Since Kamehameha V had no children, Article 22 of the 1864 Constitution provides that a “successor shall be the person whom the Sovereign shall appoint with the consent of the Nobles, and publicly proclaim as such during the King’s life; but should there be no such appointment and proclamation, and the Throne should become vacant, then the Cabinet Council, immediately after the occurring of such vacancy, shall cause a meeting of the Legislative Assembly, who shall elect by ballot some native Ali‘i of the Kingdom as Successor to the Throne.” The Cabinet Council replaced the function of the Premier (Kuhina Nui) under the former constitution, whose office was repealed by the 1864 Constitution, and according to Article 33 would serve as a Council of Regency.

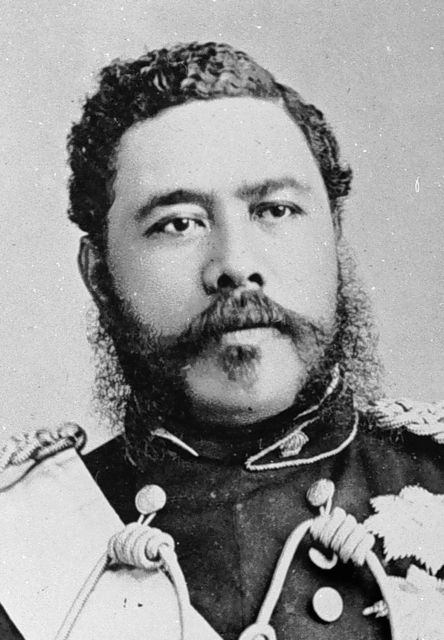

On December 11, 1872, Kamehameha V died without children and he did not appoint a successor. Kamehameha V’s Cabinet, as a Council of Regency, convened the Legislative Assembly in special session on January 8, 1873. A regent is a person or persons who serve in the absence of a monarch. In their speech to the Legislature, the Council stated:

“His late Majesty did not appoint any successor in the mode set forth in the Constitution, with the consent of the Nobles or make Proclamation thereof during his life. There having been no such appointment or Proclamation, the Throne became vacant, and the Cabinet Council immediately thereupon considered the form of the Constitution in such case made and provided, and Ordered—That a meeting of the Legislative Assembly be caused to be holden at the Court House in Honolulu, on Wednesday which will be the eighth day of January, A.D. 1873, at 12 o’clock noon; and of this order all Members of the Legislative Assembly will take notice and govern themselves accordingly. By virtue of this Order you have been assembled, to elect by ballot, some native Ali‘i of this Kingdom as Successor to the Throne. Your present authority is limited to this duty, but the newly elected Sovereign may require your services after his accession.”

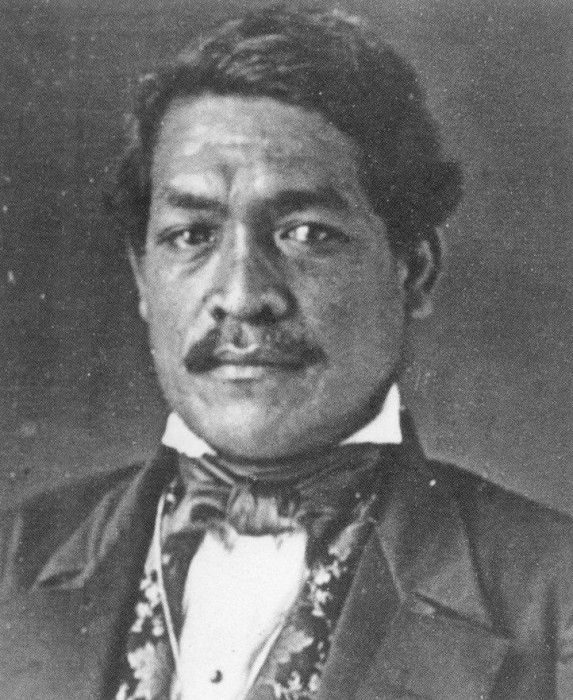

On that day the Legislature elected Lunalilo as King. From December 11, 1872 to January 8, 1873, the Kingdom was headed by a Council of Regency. Article 33 of the 1864 Constitution provides that “the Cabinet Council at the time of such decease shall be a Council of Regency…who shall administer the Government in the name of the King, and exercise all the Powers which are Constitutionally vested in the King.”

On that day the Legislature elected Lunalilo as King. From December 11, 1872 to January 8, 1873, the Kingdom was headed by a Council of Regency. Article 33 of the 1864 Constitution provides that “the Cabinet Council at the time of such decease shall be a Council of Regency…who shall administer the Government in the name of the King, and exercise all the Powers which are Constitutionally vested in the King.”

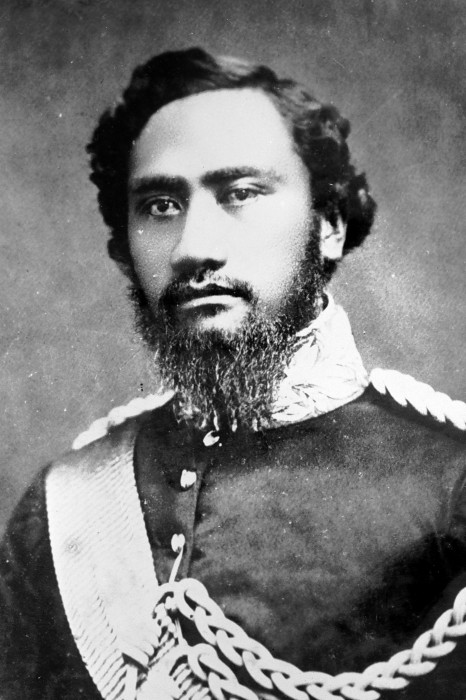

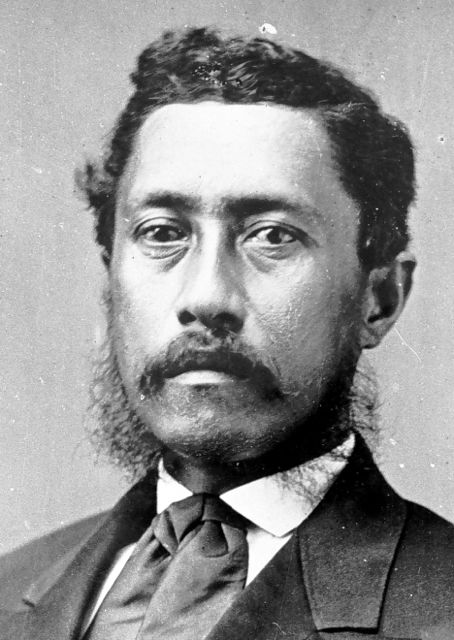

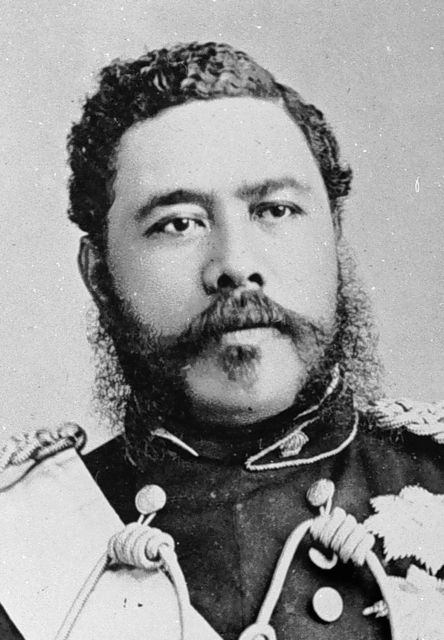

The Legislative Assembly convened again in special session on February 12, 1874 and elected King Kalakaua after Lunalilo, who died without children, failed to appoint a successor. Upon ascension to the Throne, King Kalakaua appointed his brother Prince William Pitt Leleiohoku as his heir apparent and received confirmation from the Nobles. Leleiohoku died April 10, 1877, which prompted

The Legislative Assembly convened again in special session on February 12, 1874 and elected King Kalakaua after Lunalilo, who died without children, failed to appoint a successor. Upon ascension to the Throne, King Kalakaua appointed his brother Prince William Pitt Leleiohoku as his heir apparent and received confirmation from the Nobles. Leleiohoku died April 10, 1877, which prompted  Kalakaua to immediately appoint his sister on the same day, Princess Lili‘uokalani, as his heir apparent and he received confirmation from the Nobles. An heir apparent is a person who is first in line of succession to the Throne according to Hawaiian law and cannot be displaced. An heir presumptive, however, is the person, male or female, entitled to succeed to the Throne, but can be replaced by an heir apparent pronounced according to Hawaiian law.

Kalakaua to immediately appoint his sister on the same day, Princess Lili‘uokalani, as his heir apparent and he received confirmation from the Nobles. An heir apparent is a person who is first in line of succession to the Throne according to Hawaiian law and cannot be displaced. An heir presumptive, however, is the person, male or female, entitled to succeed to the Throne, but can be replaced by an heir apparent pronounced according to Hawaiian law.

When the Legislative Assembly elected King Kalakaua in 1874, a new Stirps had effectively replaced the former Stirps, being the Kamehameha dynasty, with the Keawe-a-Heulu dynasty. Although Lunalilo was an elected King, he was of the Kamehameha dynasty, through Kamehameha’s father, Keoua. Stirps is a direct “line descending from a common ancestor,” and applies to monarchical dynasties. The Stirps for the Kamehameha Dynasty was a direct line from Kamehameha with Keopuolani, being the highest ranking of his wives. Lunalilo was not a direct descendant of Kamehameha, but a direct descendant of Kamehameha’s father, Keoua, whose son, Kalaimamahu, was Kamehameha’s half-brother.

Keawe-a-Heulu was one of the four counselor chiefs to Kamehameha I when the  islands were consolidated under one kingdom. The other three counselor chiefs were Ke‘eaumoku, Kamanawa and Kame‘eiamoku. Ke‘eaumoku was the father of Ka‘ahumanu, one of Kamehameha’s wives and who later served as Prime Minister after Kamehameha’s death in 1819. Kamanawa and Kame‘eiamoku were brothers and are also represented in the Hawaiian Kingdom’s coat of arms.

islands were consolidated under one kingdom. The other three counselor chiefs were Ke‘eaumoku, Kamanawa and Kame‘eiamoku. Ke‘eaumoku was the father of Ka‘ahumanu, one of Kamehameha’s wives and who later served as Prime Minister after Kamehameha’s death in 1819. Kamanawa and Kame‘eiamoku were brothers and are also represented in the Hawaiian Kingdom’s coat of arms.

The Kamehameha dynasty also included the descendants of Kamehameha’s other wives, other than Keopuolani who was the mother of Kamehameha II and III, and the young Princess Nahienaena. These wives and children included: Peleuli who had Maheha Kapulikoliko, Kahoanoku Kina‘u, Kaiko‘olani and Kiliwehi; Kaheiheimalie who had Kamamalu and Kina‘u, who was the mother of Kamehameha IV and V, and Premier Victoria Kamamalu.

In 1883, the Keawe-a-Heulu Stirps was formally declared at the Coronation of King Kalakaua and Queen Kapi‘olani. Princess Lili‘uokalani as the heir apparent, and the heirs presumptive, being Princess Virginia Kapo‘oloku Po‘omaikelani, Princess Kinoiki, Princess Victoria Kawekiu Kai‘ulani Lunalilo Kalaninuiahilapalapa, Prince David Kawananakoa, Prince Edward Abnel Keli‘iahonui, and Prince Jonah Kuhio Kalaniana‘ole comprised the new royal lineage.

Queen Lili‘uokalani appointed Princess Ka‘iulani as her heir apparent in 1891, but was unable to get confirmation by the Nobles because they were prevented from entering the Legislative Assembly as a result of the so-called 1887 bayonet constitution that began the insurgency. In 1917, Queen Lili‘uokalani died with no such appointment or Proclamation leaving the Throne vacant. After the Queen’s death, only Prince Kuhio was left of the heirs presumptive. All the rest had died. Of the heirs presumptive, only Prince David Kawananakoa died with lineal descendants, but these lineal descendants did not inherit the title of heirs presumptive because they were not proclaimed as such by a reigning Monarch, as King Kalakaua did by proclamation in 1883. While these lineal descendants have no claim to the Throne, they are part of the Estate of the Ali‘i (Chiefs).

Queen Lili‘uokalani appointed Princess Ka‘iulani as her heir apparent in 1891, but was unable to get confirmation by the Nobles because they were prevented from entering the Legislative Assembly as a result of the so-called 1887 bayonet constitution that began the insurgency. In 1917, Queen Lili‘uokalani died with no such appointment or Proclamation leaving the Throne vacant. After the Queen’s death, only Prince Kuhio was left of the heirs presumptive. All the rest had died. Of the heirs presumptive, only Prince David Kawananakoa died with lineal descendants, but these lineal descendants did not inherit the title of heirs presumptive because they were not proclaimed as such by a reigning Monarch, as King Kalakaua did by proclamation in 1883. While these lineal descendants have no claim to the Throne, they are part of the Estate of the Ali‘i (Chiefs).

Crown Lands

Under the 1848 Great Mahele (Division), the King and Chiefs divided their interest between themselves and the Government. Under an Act Act relating to the lands of His Majesty the King and of the Government of June 7, 1848, the King separated his lands to be called Crown lands from the Government. In the Act it stated:

Know all men by these presents, that I, Kamehameha III, by the grace of God, King of the Hawaiian Islands, have given this day of my own free will and have made over and set apart forever to the chiefs and people the larger part of my royal land, for the use and benefit of the Hawaiian Government, therefore by this instrument I hereby retain (or reserve) for myself and for my heirs and successors forever, my lands inscribed at pages 178, 182, 184, 186, 190, 194, 200, 204, 206, 210, 212, 214, 216, 218, 220, 222, of this book, these lands are set apart for me and for my heirs and successors forever, as my own property exclusively.

The “book” Kamehameha was referencing the page numbers was the 1848 Buke Mahele also called the Mahele Book.

In 1863, the Hawaiian Kingdom Supreme Court decided a case titled In the Matter of the Estate of His Majesty Kamehameha IV, 2 Haw. 715 (1863). The case centered on dower rights of Queen Kalama wife of Kamehameha III and Queen Emma wife of Kamehameha IV. The case also clarified who are the successors to the nearly one million acres of Crown land. The Supreme Court stated:

By the said Act, which is entitled “An Act relating to the lands of his Majesty the King and of the Government,” the lands reserved to the then reigning sovereign, descend in fee, the inheritance being limited to the successors to the throne, each successive possessor having the right to dispose of the same as private property.

The heirs and successors to the Crown lands are successors to the throne and not the family. In 1864, Kamehameha V asked the Legislature to remove all encumbrances such as mortgage liens on the property that had greatly encumbered the Crown lands.

That year on January 3, the Legislature passed An Act to Relieve the Royal Domain from Encumbrances (January 3, 1865).This Act authorized the Minister of Finance to issue government bonds up to $30,000.00, and the money received through the bonds would pay off the debt lenders had on the Crown in order to release the mortgages. After the debts were cleared, the Act made Crown lands inalienable and limited the ownership of tenants to 30 year leases. By making the Crown lands inalienable they were no longer capable of being mortgaged.

The Act also established a Board of Commissioners of Crown Lands who collected the lease rent. The Commissioners of Crown Lands managed the purse of the Crown. There was no tax that the people paid for to maintain the office of the Crown.

Currently, there are pretenders to the Estate of the Crown. Some claims are well known, while others are not, but all claims to the Crown lands have no basis in Hawaiian law because Her late Majesty Queen Lili‘uokalani did not appoint and thereafter proclaim her successor in accordance with the law as it was done in the past. The office of the Crown can only be filled by an election by the Legislative Assembly as it was done in the case of King Lunalilo in 1873 and King Kalakaua in 1874.

The Estate of Nobles (Chiefs)

The political class of Ali‘i is an integral component of the Hawaiian Kingdom and its government and has its origin deeply rooted in Polynesian society. The entire land system of the Kingdom that continues to exist today is grounded and based on actions taken by the Ali‘i such as the granting of Royal Patents, Land Commission Awards, and the Great Land Division (Mahele) between the Government and Chiefs, which also set the terms of division between both the Government and Chiefs and native tenants desiring to get a fee-simple title to their lands.

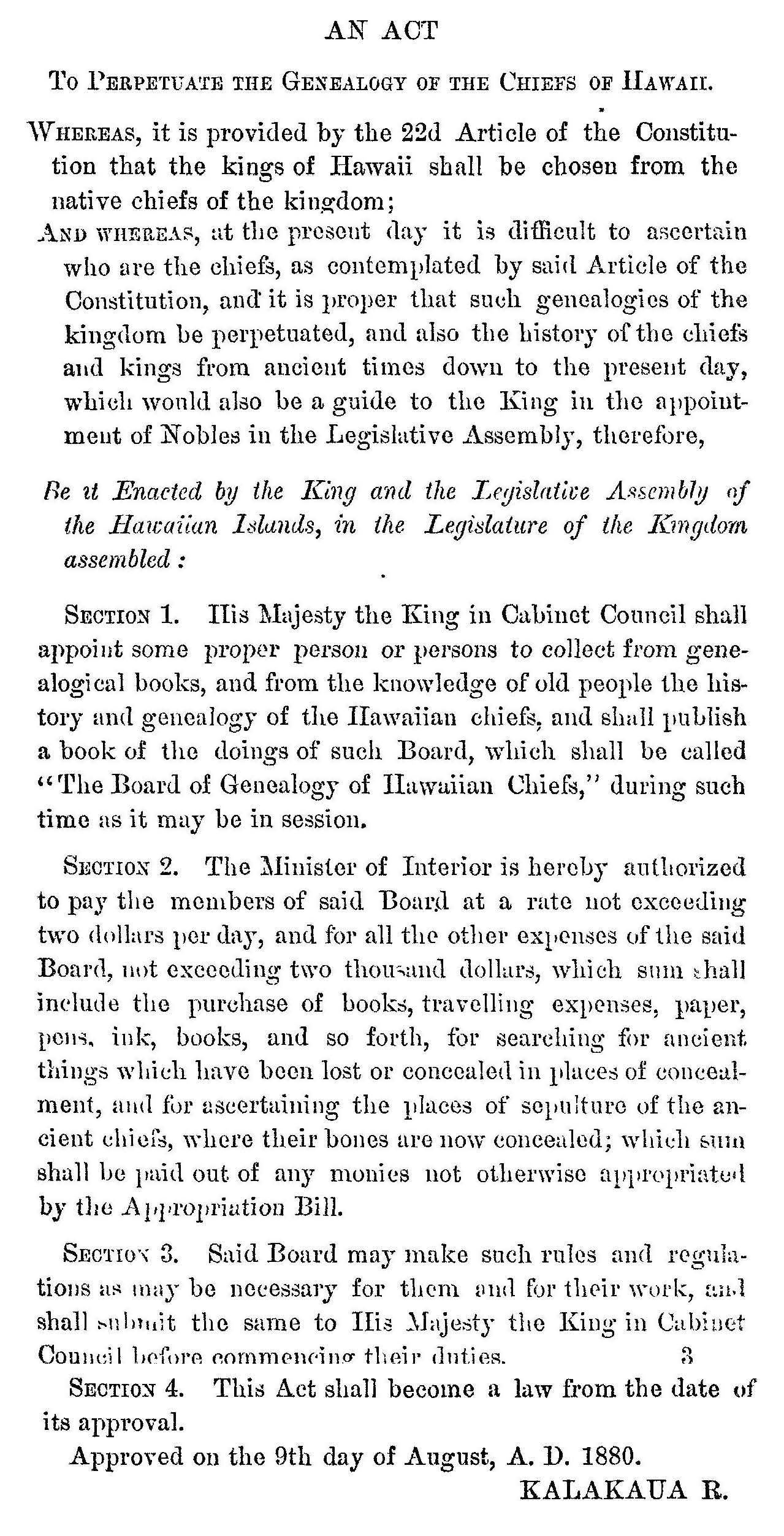

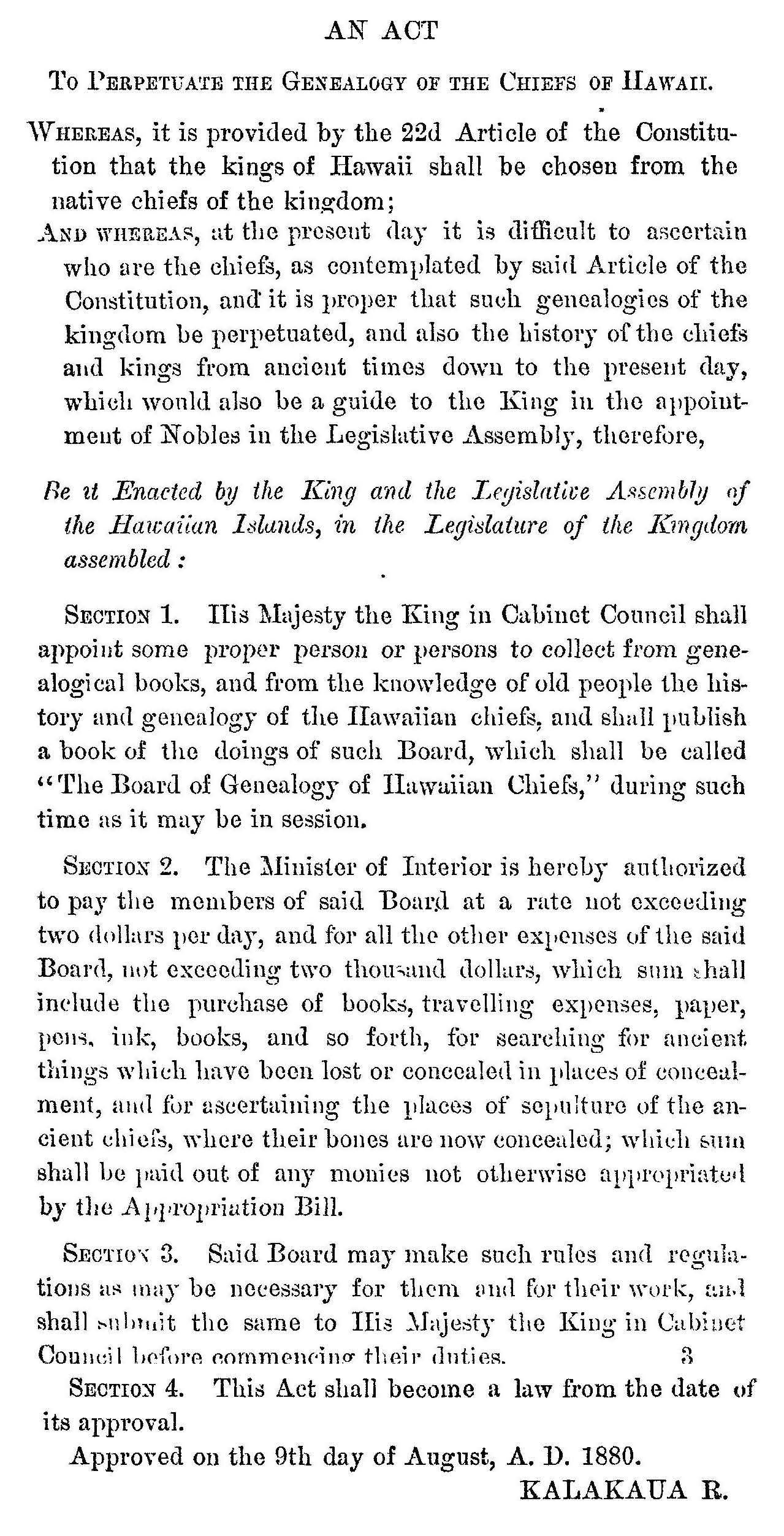

In 1880, confusion as to who comprises the Hawaiian nobility got the Hawaiian Legislature to enact “An Act to Perpetuate the Genealogy of the Chiefs of Hawaii.” In the preamble of the act it stated, “at the present day it is difficult to ascertain who are the chiefs, as contemplated by said Article of the Constitution, and it is proper that such genealogies of the kingdom be perpetuated.”

According to the Rules of the Board, their principle duties are: “1. To gather, revise, correct and record the Genealogy of Chiefs. 2. To gather, revise, correct and record all published and unpublished Ancient Hawaiian History. 3. To gather, revise, correct and record all published and unpublished Meles (Songs), and also to ascertain the object and the spirit of the Meles, the age and the History of the period when composed and to note the same on the Record Book. 4. To record all the tabu customs of the Mois (Kings) and Chiefs.”

According to the Rules of the Board, their principle duties are: “1. To gather, revise, correct and record the Genealogy of Chiefs. 2. To gather, revise, correct and record all published and unpublished Ancient Hawaiian History. 3. To gather, revise, correct and record all published and unpublished Meles (Songs), and also to ascertain the object and the spirit of the Meles, the age and the History of the period when composed and to note the same on the Record Book. 4. To record all the tabu customs of the Mois (Kings) and Chiefs.”

In its Report in 1884, the Board stated it was examining copies of genealogical books by Kamokuiki, Kaoo, Kaunahi, Unauna, Hakaleleponi, Piianaia, Kalaualu and David Malo, and that the “Board has not entered into revision of these books and those written by foreign historians as the time has been taken up mostly in attesting the genealogy of those that have applied to have their genealogy established.” The Board also reported, that it “has avoided entering into controversies with the genealogical discussions that have been going on for a year or more in the local Hawaiian newspapers, as these discussions have been more or less conducted in a partisan spirit instead of on scientific principles. They loose the merit of usefulness by the hostilities assumed by the contending writers.”

On July 5, 1887, the newly appointed Cabinet Council and two members of the Supreme Court committed the high crime of treason by coercing King Kalakaua to sign a new constitution under threat of assassination. This so-called constitution came to be known as the Bayonet Constitution and was never submitted to the Legislative Assembly for approval, which is required under law. Hawaiian constitutional law provides that any proposed change to the constitution must be submitted to the Legislative Assembly, and upon majority agreement, would be deferred to the next legislative session for action. Once the next legislature convened, and the proposed amendment or amendments were “agreed to by two-thirds of all members of the Legislative Assembly, and be approved by the King, such amendment or amendments shall become part of the Constitution of this country (Article 80, 1864 Constitution).”

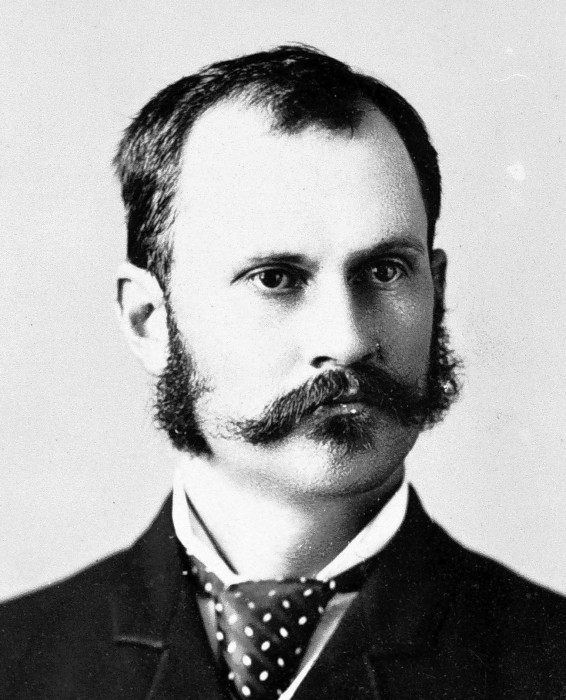

This so-called constitution was drafted by a select group of twenty individuals and effectively placed control of the Legislature and Cabinet in the hands of individuals who held foreign allegiances, which led to the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian government by the United States of America. The leader of this insurgency, Lorrin Thruston, was the Minister of the Interior, and he refused to fund the Board of Genealogists

This so-called constitution was drafted by a select group of twenty individuals and effectively placed control of the Legislature and Cabinet in the hands of individuals who held foreign allegiances, which led to the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian government by the United States of America. The leader of this insurgency, Lorrin Thruston, was the Minister of the Interior, and he refused to fund the Board of Genealogists  as required by law. In a letter to Her Royal Highness Princess Po‘omaikelani, President of the Genealogical Board, dated July 29, 1887, Thurston writes, “I beg to acknowledge receipt of your communication of the 27th inst. in which you state the labors of the board need not be suspended because the appropriation cannot be paid. There can, of course, be no objection to a continuation of the work of the Board of Genealogy so long as it is carried out without expense to the Government.”

as required by law. In a letter to Her Royal Highness Princess Po‘omaikelani, President of the Genealogical Board, dated July 29, 1887, Thurston writes, “I beg to acknowledge receipt of your communication of the 27th inst. in which you state the labors of the board need not be suspended because the appropriation cannot be paid. There can, of course, be no objection to a continuation of the work of the Board of Genealogy so long as it is carried out without expense to the Government.”

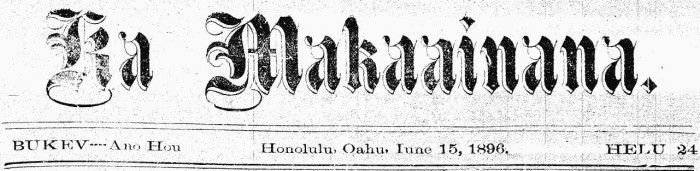

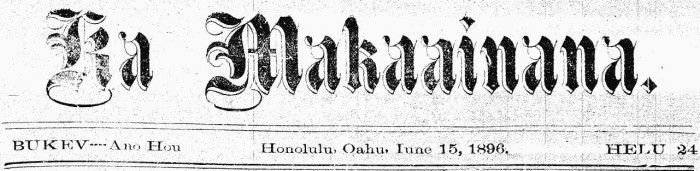

Despite the lack of government funding and the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government, the Board continued their work to compile the genealogies of Hawaiian Chiefs (Mo‘okua‘auhau Ali‘i) that were eventually published in the Ka Maka‘ainana newspaper in the year 1896.

The acting Government is providing these publications, which are in the Hawaiian language, to the public at large with a link to the original publication in PDF by date of the publication. The names of Hawaiian Chiefs below are printed as they are written in the published genealogies, which did not have any diacritical markers such as the ‘okina or kahako. The English translations of these publications can be drawn from Edith Kawelohea McKinzie and Ishmael W. Stagner, II, Hawaiian Genealogies, vol. 1. A basic glossary of terms that can be used to understand the published genealogies are:

“k” is short for kane (male)

“w” is short for wahine (female)

noho (to live with, but used to mean the same as marriage)

mare (married)

a‘ohe pua (no lineal descendants)

kuamo‘o (lineage)

kuauhau (genealogy)

loa‘a (had)

mo‘o kuauhau (genealogical succession)

June 1, 1896—Genealogies of King Kamehameha IV and King Lunalilo, both of whom died without lineal descendants.

June 8, 1896—Genealogies of King Kalakaua and Queen Liliuokalani, both of whom died without lineal descendants.

June 15, 1896—Genealogy of Princess Kaiulani, who died without lineal descendants.

June 29, 1896—Genealogies of Queen Kapiolani, who died without lineal descendants; Prince Jonah Kuhio Kalanianaole who died without lineal descendants; and David Kawananakoa.

July 6, 1896—Genealogies of William Piikoi Wond, Lydia Kamakee Cummins, and Maraea Cummins; Daisy Napulahaokalani, Eva Kuwailanimamao, Roberto Kalaninuikupuaikalaninui Keoua and Virginia Kahoa Kaahumanu Kaihikapumahana.

July 13, 1896—Genealogy of Albert Kekukailimoku Kunuiakea who died without lineal descendants.

July 20, 1896—Genealogies of Princess Bernice Pauahi who dies without lineal descendants, Princess Ruth Keelikolani who died without lineal descendants, and John Kamehamehanui who died without lineal descendants.

July 27, 1896—Genealogies of Alexandrina Leihulu Kapena who died without lineal descendants, Edward Kamakau Lilikalani, and Annie Palekaluhi Kaikioewa who died without lineal descendants.

August 3, 1896—Genealogies of Sabina Kahinu Beckley, Frederick Kahapula Beckley, Jr., and Frederica Beckley; Leander Kaonowailani, Violet Kahaleluhi Kinoole, Grace Namahana i Kaleleokalani, Frederick Malulani, George Heaalii and Benjamin Kameeiamoku; William Kauluheimalama Beckley, Henry Hoolulu Beckley, Juanita Beckley, and George Mooheau Beckley, Jr.; Henry Hoolulu Pitman, Mary Kinoole (Mrs. Mary Ailau), and Benjamin Pitman, Jr.; Robert Hoapili Baker, Henry Kanuha, and Rev. J. Kauhane of Kau.

August 10, 1896—Genealogies of William Hoapili Kaauwai, Jr., Luka Kaauwai and Lydia Kahanu Kaauwai; Mary Parker (Mrs. Maguire), Eva Kalanikauleleiaiwi Kahiluonapuaonahonoapiilani Parker, Helen Umiokalani Parker, John Palmer Parker, Hattie Kaonohilani Parker, Palmer Kuihelani Parker, Samuel Keaoililani Parker, Ernest Napela Parker, and James Kekookalani Parker.

August 17, 1896—Genealogies of Lydia Kamakanoe Kanehoa, Albert Kaleinoanoa Kanehoa, Jno Kupakee Kanehoa, Davida K. Hoapili Kanehoa, and Maria Kalehuaikawekiu Kanehoa; Hoapiliwahine-a-Kanehoa; and the children of Makainai-a-Kuakini and Kauina, being Jesse Makainai, Keeaumoku, Kapaleiliahi, Kaumaumaeha, Hoapili Liilii, and Paulo Hoapili; Henry St. John Kaleookekoi Nahaolelua, George William Lua Nahaolelua, John Vivian St. John Kapokini Nahaolelua, Charles Kalaninoheainamoku Nahaolelua, Albert Kamainiualani Nahaolelua, Alexander Pahukula Kuanamoa Nahaolelua, Elizabeth Alice Kalakini Nahaolelua, and Emma Rhoda Kaaiohelo Nahaolelua; William Kapahukula Enelani Stevens who died without lineal descendants, and Keliikui Stevens who also died with lineal descendants.

August 24, 1896—Genealogies of Rose Kekupuohi Simerson, William Kuakini Simerson and Isaac Kaleialii Simerson; and the children of Annie Niulii and Kahaleaahu, being Helen Kalolowahilani, John Paalua and David Kauluhaimalama.

August 31, 1896—Genealogies of Annie Thelma Kahiluonapuaonahonoapiilani Parker; Kahaule-o-Kuakini and Mrs. Maluhi Reis; John Meek, Jr.; and Maraea Kaoaopa died without lineal descendants.

September 7, 1896—Genealogies of Adele Mikahala Unauna, John Koii Unauna, Maraea Kapumakokoulaokalani Unauna, Kaniu Unauna, Kahelemanolani Unauna, Jane Kulokuloku Unauna, Hattie Kaauamookalani Unauna and James Kalimaila Unauna; Julia Kailimahuna Koii, Lydia Kahuakai Koii, Lydia Kahuakai Koii, David Koii who died without lineal descendants, and Esther Namahana Koii; Julia Kapakuialii Kalaninuipoaimoku Doiron and Moses Koii Luhaukapewa Doiron; William Kahoapili Kekohimoku Alohikea, Alfred Unauna Alohikea, David Kauahiaalaiwilani Kaili; Alexander Boki Reis, Palmyra Lonokahikini Reis, and Helen Kekumualii Reis; and Helina Kaiwaokalani Maikai, David Unualoha Maikai, Samuela Kahilolaamea Maikai, and Abigaila Kalanikuikepo‘oloku Maikai.

October 5, 1896—Genealogies of Stella Keomailani Cockett who died without lineal descendants; and the child of Kekulu and Kaiakoili, being David Kalani.

October 19, 1896—Genealogies of Tilly Kaumakaokane Cummins, Thomas Keauiaole Cummins, and John T. Walker Cummins; King Keaweaua Mersberg, James Kahai Mersberg, Jr., Lily Kahalewai Mersberg, Marie Mersberg, Lydia Mersberg, Jane Piilani Mersberg, and Charles Mersberg; John Adams Kaenakulani Cummins, Thomas C. Kaihikapu Cummins, and Raplee Kawelokalani Cummins; May Kaaolani Cummins Creighton; Flora Kahanolani Cummins; children of Kekupuo-i; Ponilani Kaiama (w), Margaret Loe Kaiama, Esther Nahaukapuokalani Kaiama, Levi Kaiama and Keliimaikai Kaiama; Grace Kamaikui Piianaia, Niaupio Piianaia, and Heulumanawaokalani Piianaia (k); Phoebe Ulualoha Wilcox; and Daniel Kekuhio Keliiaa and Kekukamaikalani Keliiaa.

October 26, 1896—Genealogy of Katherine Kaonohiulaokalani Brown who died without lineal descendants.

November 2, 1896—Genealogy Hana Kaunahi and Akahi who both died without lineal descendants.

After the death of Prince Kuhio Kalaniana‘ole on January 13, 1922, the Associated Press reported, “Fourteen chiefs selected by the committee from the high chiefs of Hawaii will bear the casket of Prince Kuhio at the funeral Sunday morning. The selection are Henry P. Beckley, Edwin Kea, David Hoapili, Sr., Kaliinonao, John Nahaolelua, Alex Nahaolelua, Jesse Makainai, William Simerson, John H. Wise, William Taylor, Geo. Kalohapauole, David Maikai, Ahapuni Boyd, Clement Parker, Samuel Parker, Jr., as bearer of orders and David Hoapili, Jr. as bearer of the tabu stick.” These men were selected from the Estate of Ali‘i (Chiefs).

Any person today who is a direct lineal descendant of the Hawaiian Chiefs identified in these published genealogies belong to the Estate of Nobles (Chiefs), and are eligible to be appointed as Nobles in the Legislative Assembly and/or to the Throne in accordance with Hawaiian law.

Any person today who is a direct lineal descendant of the Hawaiian Chiefs identified in these published genealogies belong to the Estate of Nobles (Chiefs), and are eligible to be appointed as Nobles in the Legislative Assembly and/or to the Throne in accordance with Hawaiian law.

The Estate of the People

Any person today who is a direct lineal descendant of a Hawaiian subject before the United States occupation began on January 17, 1893, belong to the Estate of the People.