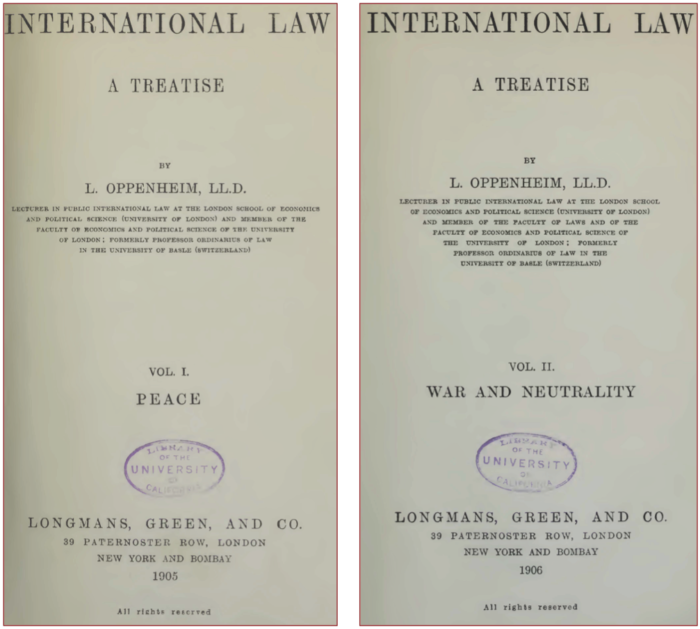

When the United States assumed control of its installed puppet regime under the new heading of Territory of Hawai‘i in 1900, and later the State of Hawai‘i in 1959, it surpassed “its limits under international law through extraterritorial prescriptions emanating from its national institutions: the legislature, government, and courts (Eyal Benvenisti, The International Law of Occupation (1993), p. 19).” The legislation of every state, including the United States of America and its Congress, are not sources of international law.

In The Lotus case, (1927 PCIJ Series A, No. 10, p. 18), the Permanent Court of International Justice stated that “Now the first and foremost restriction imposed by international law upon a State is that—failing the existence of a permissive rule to the contrary—it may not exercise its power in any form in the territory of another State.” According to Judge Crawford, derogation of this principle will not be presumed (James Crawford, The Creation of States in International Law (2nd ed., 2006), p. 41).

Since Congressional legislation has no extraterritorial effect, it cannot unilaterally establish governments in the territory of a foreign state. According to the U.S. Supreme Court, “[n]either the Constitution nor the laws passed in pursuance of it have any force in foreign territory unless in respect of our own citizens, and operations of the nation in such territory must be governed by treaties, international understandings and compacts, and the principles of international law (United States v. Curtiss Wright Export Corp., 299 U.S. 304, 318 (1936)).”

The U.S. Supreme Court also concluded that “[t]he laws of no nation can justly extend beyond its own territories except so far as regards its own citizens. They can have no force to control the sovereignty or rights of any other nation within its own jurisdiction (The Apollon, 22 U.S. 362, 370 (1824)).” Therefore, the State of Hawai‘i cannot claim to be a government as its only claim to authority derives from Congressional legislation that has no extraterritorial effect. As such, international law defines the State of Hawai‘i as an organized armed group.

According to Henckaerts and Doswald-Beck, Customary International Humanitarian Law, Vol. I (2009), p. 14, “organized armed groups … are under a command responsible to that party for the conduct of its subordinates.” They explain that “this definition of armed forces covers all persons who fight on behalf of a party to a conflict and who subordinate themselves to its command.” Article 1 of the 1907 Hague Convention, IV, states:

“The laws, rights, and duties of war apply not only to armies, but also to militia and volunteer corps fulfilling the following conditions: (1) To be commanded by a person responsible for his subordinates; (2) To have a fixed distinctive emblem recognizable at a distance; (3) To carry arms openly; and (4) To conduct their operations in accordance with the laws and customs of war.”

In 2013, State of Hawai‘i v. Kaulia, 128 Hawai‘i 479, 486 (2013), the State of Hawai‘i Supreme Court responded to a defendant who “contends that the courts of the State of Hawai‘i lacked subject matter jurisdiction over his criminal prosecution because the defense proved the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the illegitimacy of the State of Hawai‘i government, with “whatever may be said regarding the lawfulness” of its origins, “the State of Hawai‘i … is now, a lawful government.” This is a bold statement to be made by the Supreme Court without providing any evidence of its lawfulness other than declaring its lawfulness.

From a standpoint of evidence, the jurisdiction of the State of Hawai‘i court stems from its lawfulness. This lawfulness, however, is allowed to be challenged by a defendant under Rule 12(b)(1) of the Hawai‘i Rules of Civil Procedure, which provides for a defendant to file a motion to dismiss based upon subject matter jurisdiction. In Nishitani v. Baker, 82 Haw. 281, 289 (1996), the State of Hawai‘i Intermediate Court of Appeals (ICA) stated,

“that although the governments of the State of Hawaii and the United States had recently acknowledged the illegality of the overthrow of the Kingdom, neither recognizes that the Kingdom exists at the present time (citations omitted). Because the defendant had ‘presented no factual (or legal) basis for concluding that the Kingdom exists as a state in accordance recognized attributes of a state’s sovereign nature,’ we determined that the defendant had failed to meet his burden under HRS ß 701-115(2) (1993) of proving his defense of lack of jurisdiction. … [And] where immunity claims are raised as a defense to jurisdiction, the burden is on the defendant to establish his immunity status.”

The citation by the ICA of HRS ß 701-115(2) states, “No defense may be considered by the trier of fact unless evidence of the specified fact or facts has been presented.” In other words, it is incumbent on the defendant to present the evidence if he is challenging the jurisdiction of the court. In Kaulia, there was no evidentiary hearing by the trial court because the trial court denied Kaulia his right to present ‘specified fact or facts” that conclude “the Kingdom exists as a state in accordance recognized attributes of a state’s sovereign nature.”

Kaulia’s attorney sought to have Dr. Keanu Sai serve as an expert witness. Dr. Sai had been admitted in both criminal and civil proceedings as an expert witness on the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State under international law.

“[O]n March 15, 2010, Kaulia filed a Motion to Dismiss Complaint (Motion to Dismiss) challenging the court’s jurisdiction over the case based on the existence of the Kingdom of Hawai‘i (Kingdom). At the hearing on the Motion to Dismiss, the court confirmed that in off-the-record conferences it had denied Kaulia’s request for an evidentiary hearing to call witnesses, including one Dr. Keanu Sai, to establish the existence of the Kingdom. The court then denied Kaulia’s Motion to Dismiss.” State of Hawai‘i v. Kaulia,128 Haw. 479, 482 (2013).

On appeal, the ICA held that “[t]he Circuit Court did not err in precluding Kaulia from calling a witness to present evidence concerning the Kingdom of Hawai‘i in support of his motion to dismiss case for lack of jurisdiction (State of Hawai‘i v. Kaulia, 127 Haw. 414 (2012),” despite the ICA’s previous decision in State of Hawai‘i v. Lorenzo, 77 Haw. 219, 221 (1994), that “it was incumbent on Defendant to present evidence supporting his claim…that the Kingdom exists as a state in accordance with recognized attributes of a state’s sovereign nature.” According to The American Heritage Dictionary (2nd ed., 1982), the term ‘incumbent’ is defined as “[i]mposed as an obligation or duty; obligatory.” Legally, the phrase ‘incumbent on’ means “mandatory, obligatory, requisite (William C. Burton, Legal Thesaurus 754 (2nd ed., 1992)).”

Like the ICA, the Supreme Court in blatant disregard of the ICA cases of Lorenzo and Baker, “rejected Kaulia’s argument that the circuit court erred in precluding Kaulia from calling a witness to present evidence concerning the existence of the Kingdom in support of his Motion to Dismiss (State of Hawai‘i v. Kaulia, 128 Haw. 479, 487 (2013)).”

The irony of this whole matter is that the Supreme Court cited Lorenzo and Baker as its basis to deny Kaulia’s argument, which is that “it was incumbent on Defendant to present evidence supporting his claim…that the Kingdom exists as a state.” The decisions by the Circuit Court, ICA and Supreme Court in Kaulia clearly run counter to HRS ß 701-115(2). According to this flawed logic, so long as the trier of fact (judge) can prevent the defense from presenting “evidence of the specified fact or facts” it does not need to consider it. Prosecutors and plaintiff’s attorneys now cite State of Hawai‘i v. Kaulia as the precedent case to deny defendants’ motions to dismiss. This is a feeble attempt to close the door that they opened in 1994 in State of Hawai‘i v. Lorenzo.

The State of Hawai‘i courts have established an echo chamber to shield themselves from the precedence set by the courts themselves in Lorenzo and Baker. The term echo chamber is “widely used in today’s lexicon, that describes a situation where certain ideas, beliefs or data points are reinforced through repetition of a closed system that does not allow for the free movement of alternative or competing ideas or concepts.” As Mohajer, The Little Book of Stupidity: How We Lie to Ourselves and Don’t Believe Others 20, 7 (2015), wrote:

“The confirmation bias is so fundamental to [our] development and [our] reality that you might not even realize it is happening. We look for evidence that supports our beliefs and opinions about the world but excludes those that run contrary to our own… In an attempt to simplify the world and make it conform to our expectations, we have been blessed with the gift of cognitive biases.”

While this game of hide and seek is being played out by the State of Hawai‘i judiciary, these actions constitute violations of the 1907 Hague and the 1949 Geneva Conventions, which have been codified by the Congress under 18 U.S.C. §2441—War crimes.

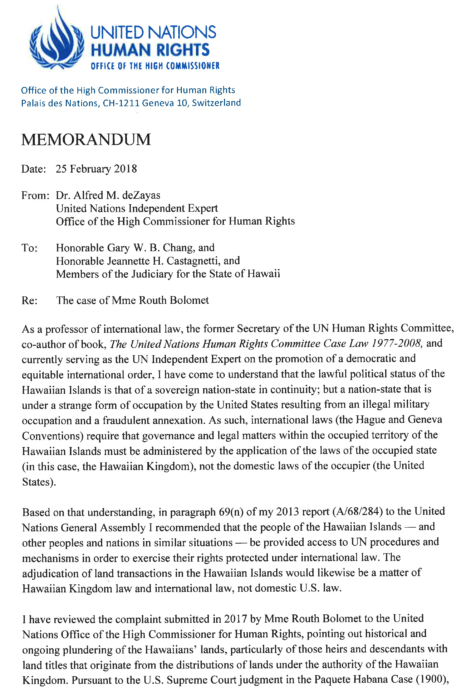

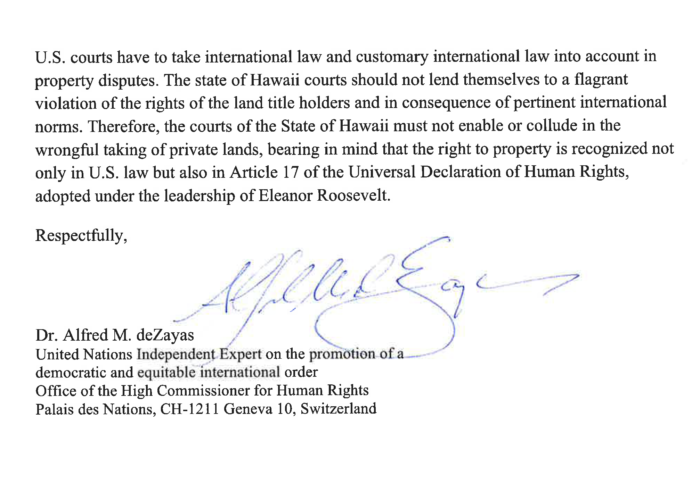

The United Nations Independent Expert, Dr. Alfred M. deZayas notified the State of Hawai‘i judiciary to not “plunder…enable or collude.” Plunder is another word for the war crime of pillaging, which is prohibited under Article 28 of the 1907 Hague Convention, IV, 18 U.S.C. §2441(c)(2). To deny a person of a fair and regular trial is also a war crime under Article 147 of the 1949 Geneva Convention, IV, 18 U.S.C. §2441(c)(2). The terms enable and collude are terms associated with conspiring to commit war crimes.

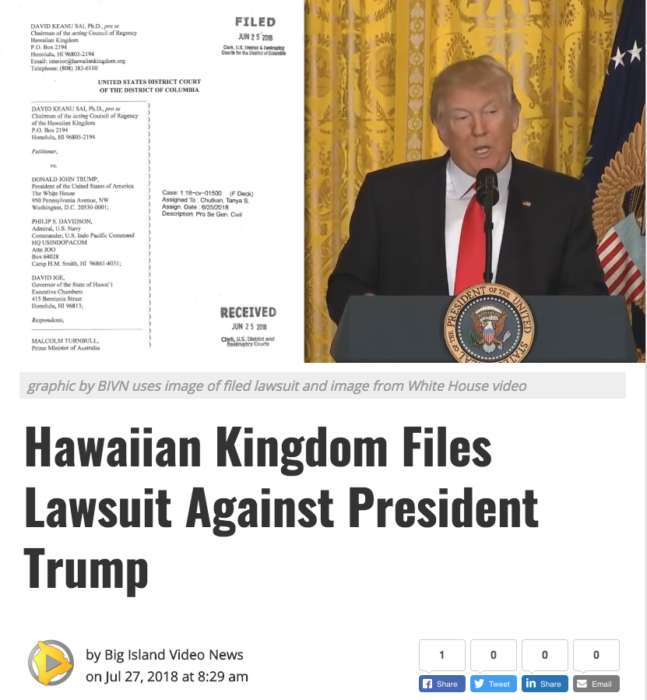

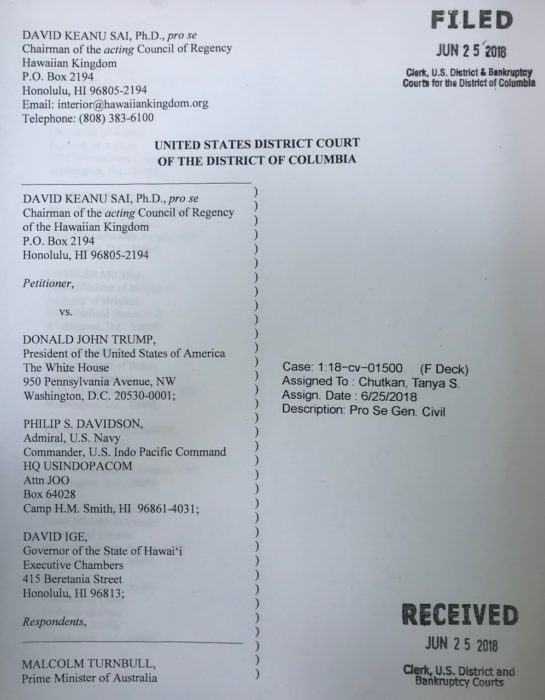

On May 10, 2018, Mrs. Routh Bolomet, a Hawaiian-Swiss citizen, provided Dr. Keanu Sai with a remarkable document that came out of the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights in Geneva, Switzerland, regarding Hawai‘i. Mrs. Bolomet told Dr. Sai that it was her hope that the document authored by

On May 10, 2018, Mrs. Routh Bolomet, a Hawaiian-Swiss citizen, provided Dr. Keanu Sai with a remarkable document that came out of the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights in Geneva, Switzerland, regarding Hawai‘i. Mrs. Bolomet told Dr. Sai that it was her hope that the document authored by  The President of the Council,

The President of the Council,

His memorandum also serves as an amendment to the 2013 Report correcting the legal status of Hawai‘i as an occupied State and not an issue of self-determination for an indigenous group of people. In line with this change, Article 69(e) of his recommendations is more appropriate, “States should ratify the individual complaints procedures of the United Nations human rights treaties, adhere to and utilize the inter-State complaints procedures, and globalize the reach of the International Criminal Court.”

His memorandum also serves as an amendment to the 2013 Report correcting the legal status of Hawai‘i as an occupied State and not an issue of self-determination for an indigenous group of people. In line with this change, Article 69(e) of his recommendations is more appropriate, “States should ratify the individual complaints procedures of the United Nations human rights treaties, adhere to and utilize the inter-State complaints procedures, and globalize the reach of the International Criminal Court.”

This process, which is known as Americanization and which is a war crime, has nearly obliterated the national consciousness of the Hawaiian Kingdom in the minds of Hawai‘i’s people, and by extension, the international community. Samuel Damon, an insurrectionist and traitor to Hawai‘i, stated in 1895, “If we are ever to have peace and annexation the first thing to do is to obliterate the past.” Damon also served as Trustee for the

This process, which is known as Americanization and which is a war crime, has nearly obliterated the national consciousness of the Hawaiian Kingdom in the minds of Hawai‘i’s people, and by extension, the international community. Samuel Damon, an insurrectionist and traitor to Hawai‘i, stated in 1895, “If we are ever to have peace and annexation the first thing to do is to obliterate the past.” Damon also served as Trustee for the

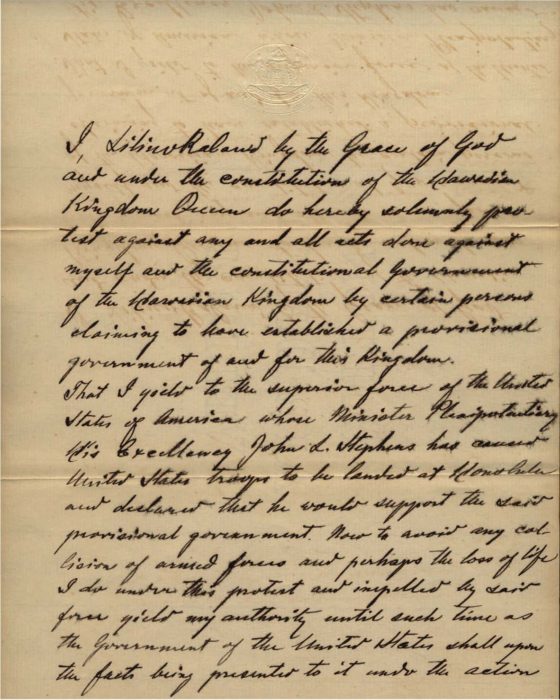

These two days will mark 125 years of the American invasion of the Hawaiian Kingdom on January 16th and the conditional surrender of the Hawaiian government by Queen Lili‘uokalani on January 17th calling upon the President of the United States to investigate the unlawful actions taken by its diplomat who ordered the landing of U.S. troops. While in the Palace, the Queen drafted the following conditional surrender to the United States:

These two days will mark 125 years of the American invasion of the Hawaiian Kingdom on January 16th and the conditional surrender of the Hawaiian government by Queen Lili‘uokalani on January 17th calling upon the President of the United States to investigate the unlawful actions taken by its diplomat who ordered the landing of U.S. troops. While in the Palace, the Queen drafted the following conditional surrender to the United States:

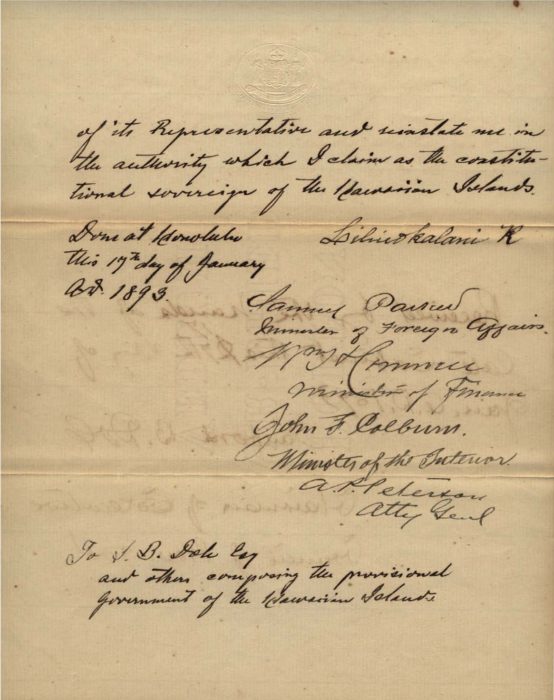

After investigating the overthrow of the Hawaiian government, President Cleveland

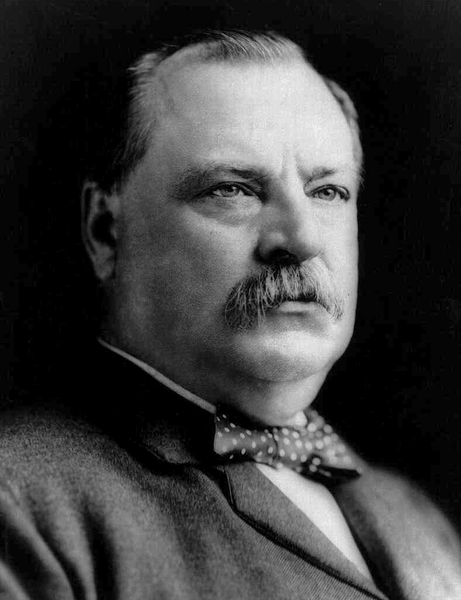

After investigating the overthrow of the Hawaiian government, President Cleveland  The political determination by President Cleveland, regarding the actions taken by the military forces of the United States since January 16, 1893, was the same as the political determination by President Roosevelt regarding actions taken by the military forces of Japan on December 7, 1945 in its attack of Pearl Harbor. On December 8, 1941, President Roosevelt

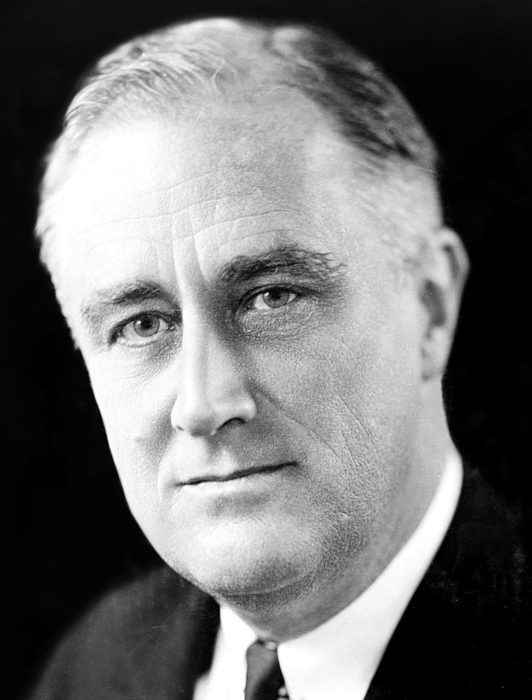

The political determination by President Cleveland, regarding the actions taken by the military forces of the United States since January 16, 1893, was the same as the political determination by President Roosevelt regarding actions taken by the military forces of Japan on December 7, 1945 in its attack of Pearl Harbor. On December 8, 1941, President Roosevelt  Professor William Schabas

Professor William Schabas