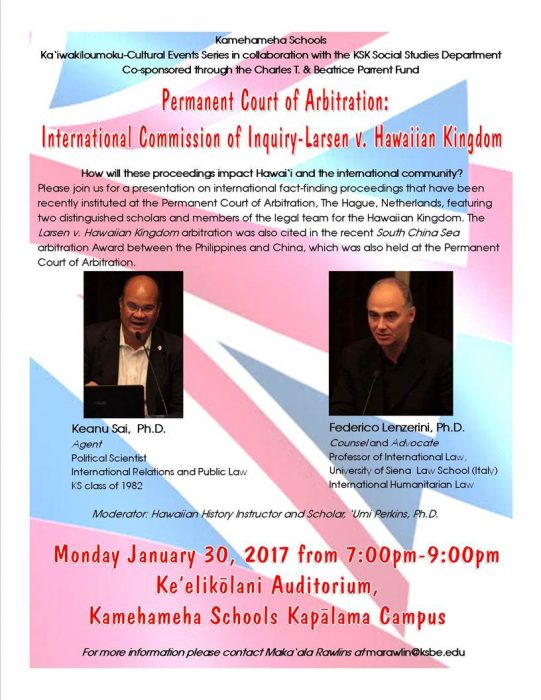

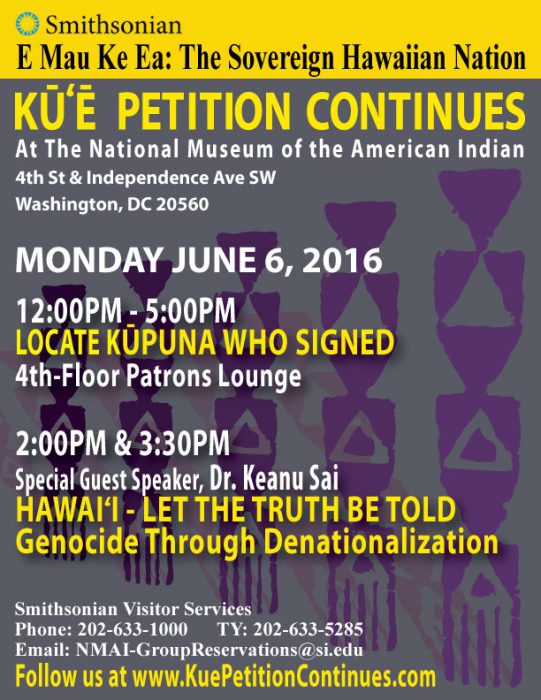

International Proceedings Presented at the Kamehameha Schools Jan. 30

11

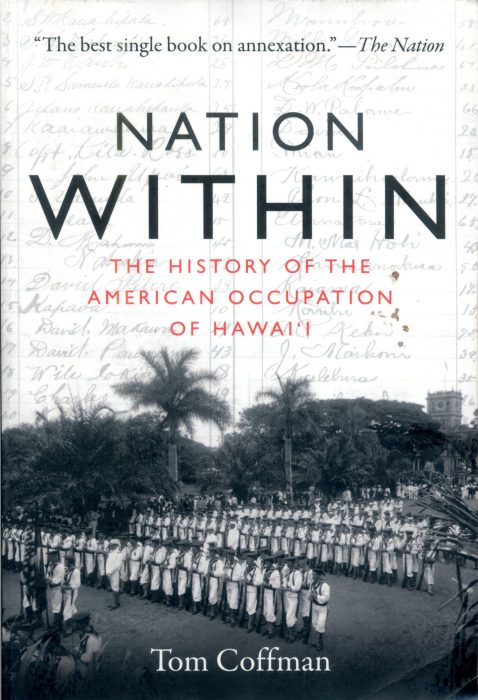

In 2016, Duke University Press published Tom Coffman’s Nation Within: The History of the American Occupation of Hawai‘i. While this book has been in circulation since 1998, it is the first time that an academic publisher has put its name to the book. The goal of Duke University Press is “to contribute boldly to the international community of scholarship.” “By insisting on thorough peer review procedures in combination with careful editorial judgment, the Press performs an intellectual gatekeeping function, ensuring that only scholarship of the highest quality receives the imprimatur of the University.”

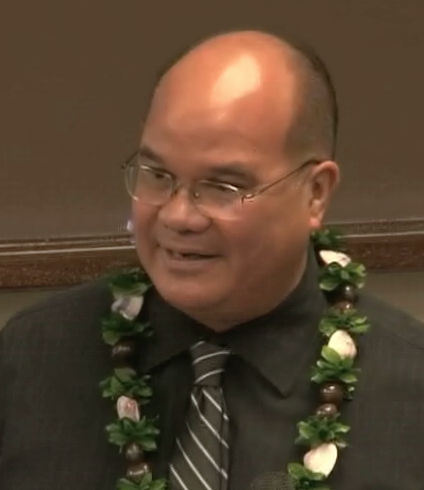

Dr. Keanu Sai, a political scientist, whose doctoral research covered the American occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom and its continued existence today as an independent State, was asked by the Hawaiian Journal of History to write a book review of Coffman’s Nation Within for its first publication in 2017. In his review, Dr. Sai reveals the “smoking gun” that was brought to his attention by Dr. Ron Williams of the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa.

***************************************************************

In Nation Within: The History of the American Occupation of Hawai‘i, Tom Coffman exhibits a radical shift by historians in interpreting political events post-1893. When Coffman first published his book in 1998, his title reflected a common misunderstanding of annexation. But in 2009, he revised the title by replacing the word Annexation with the word Occupation. Coffman admitted he made this change because of international law (p. xvi). By shifting the interpretive lens to international law, Coffman not only changed the view to occupation, but would also change the view of the government’s overthrow in 1893. While the book lacks any explanation of applicable international laws, he does an excellent job of providing an easy reading of facts for international law to interpret.

In international law, there is a fundamental rule that diplomats have a duty to not intervene in the internal affairs of the sovereign State they are accredited to. Every sovereign State has a right “to establish, alter, or abolish, its own municipal constitution [and] no foreign State can interfere with the exercise of this right” (Halleck’s International Law, 3rd ed., p. 94). For an ambassador, a violation of this rule would have grave consequences. An offended State could proceed “against an ambassador as a public enemy…if justice should be refused by his own sovereign” (Wheaton’s International Law, 8th ed., p. 301).

John Stevens, the American ambassador to the Hawaiian Kingdom arrived in the islands in the summer of 1889. As Coffman notes, Stevens was already fixated with annexation when he “wrote that the ‘golden hour’ for resolving the future status of Hawai‘i was at hand,” (p. 114) and began to collude with Lorrin Thurston (p. 116). Thurston was not an American citizen but rather a third-generation Hawaiian subject. Stevens’ opportunity to intervene and seek annexation would occur after Lili‘uokalani “attempted to promulgate a new constitution, [which] was the event Thurston and Stevens had been waiting for” (p. 120).

On January 16, Stevens orders the landing of U.S. troops and “tells Thurston that if the annexationists control three buildings—‘Iolani Palace, Ali‘iolani Hale, and the Archives—he will announce American recognition of the new government” (p. 121). The following day, “Stevens tells the queen’s cabinet that he will protect the annexationists if they are attacked or arrested by government police” (Ibid.). However, unbeknownst to Stevens, the insurgents only took over Ali‘iolani Hale, which housed “clerks of the Kingdom” (p. 125). One of the insurgents, Samuel Damon, knowing Stevens’ recognition was premature, sought to convince Lili‘uokalani that her resistance was futile because the United States had already recognized the new government, and that she should order Marshal Charles Wilson, head of the government police, to give up the police station. Wilson was planning an assault on the government building to apprehend the insurgents for treason in spite of the presence of U.S. troops.

International law clearly interprets these events as intervention and Stevens to be a “public enemy” of the Hawaiian Kingdom. This was the same conclusion reached by President Grover Cleveland, whose investigation was an indictment of Stevens and the commander of the USS Boston, Captain Gilbert Wiltse. “The lawful Government of Hawai‘i was overthrown without the drawing of a sword or the firing of a shot,” Cleveland said, “by a process every step of which, it may be safely asserted, is directly traceable to and dependent for its success upon the agency of the United States acting through its diplomatic and naval representatives” (p. 144). Because of diplomatic immunity, the United States, as the sending State, would be obliged to prosecute Stevens and Wiltse for treason under American law.

On December 20, 1893, a resolution of the U.S. Senate called for a separate investigation to be conducted by the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations. Chaired by Senator John Morgan, a vocal annexationist, the purpose of the Senate investigation was to repudiate Cleveland’s investigation and to vindicate Stevens and Wiltse of criminal liability. One week later, the Committee held its first day of hearings in Washington, DC. Stevens appeared before the Committee and fielded questions under oath on January 20, 1894. When asked by the Chairman if his recognition of the provisional government was for the “purpose of dethroning the Queen,” he responded, “Not the slightest—absolute noninterference was my purpose” (Report from the Committee on Foreign Relations— Appendix, p. 550).

After the hearings, two reports were submitted on February 26, 1894—a Committee Report and a Minority Report. The committee of eight senators was split down the middle, with Morgan giving the majority vote for the Committee Report. Half of the committee members did not believe Stevens’ testimony of his non-intervention. The Minority Report stated, “We can not concur…in so much of the foregoing report as exonerates the minister of the United States, Mr. Stevens, from active officious and unbecoming participation in the events which led to the revolution” (Ibid., p. xxxv).

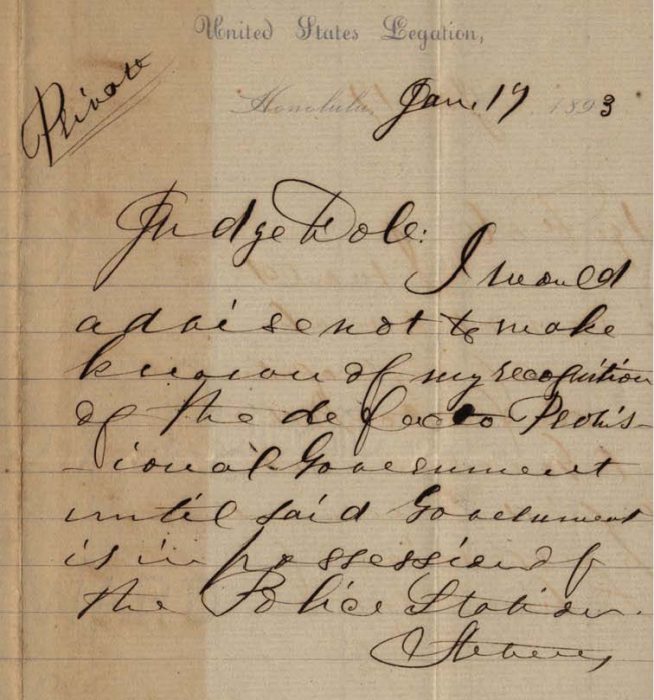

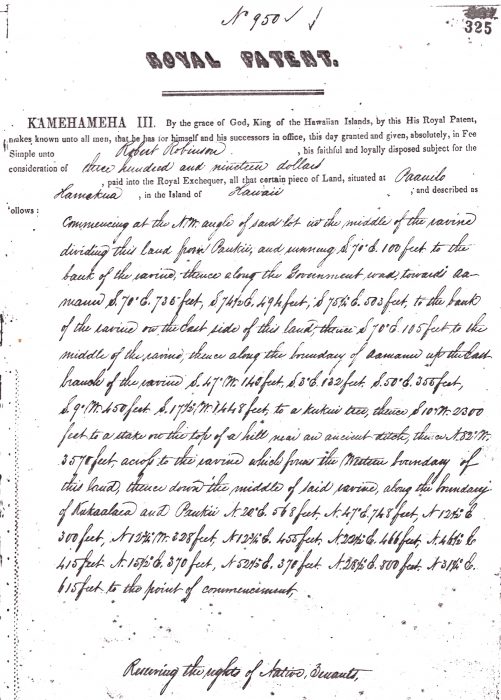

The Senate Committee’s investigation could find no direct evidence that would disprove Stevens’ sworn testimony, but in 2016, the “smoking gun” was found that would prove Stevens was a public enemy of the Hawaiian Kingdom, committed perjury before the Committee, and would no doubt have been prosecuted under the 1790 federal statute of treason. The Hawaiian Mission Houses Archives is processing a collection of documents given to them by a descendent of William O. Smith. Smith was an insurgent that served as the attorney general for Sanford Dole, so-called president of the provisional government.

The “smoking gun” is a note to Dole signed by Stevens marked “private” and written under the letterhead of the “United States Legation” in Honolulu and dated January 17, 1893. Stevens writes, “Judge Dole: I would advise not to make known of my recognition of the de facto Provisional Government until said Government is in possession of the police station.”

As a political scientist, Coffman’s book is a welcomed addition to arresting revisionist history.

Japan’s Seijo University’s Center for Glocal Studies has published, in its latest journal for 2016, an article authored by Dennis Riches titled “This is not America: The Acting Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom Goes Global with Legal Challenges to End Occupation [this is a hot link to download the article].” The word Glocal Studies is a combination of the words Global and Local Studies.

The study focused on the American occupation of Hawai‘i and its global impact, which includes war crimes. It also included an interview of Dr. Keanu Sai by the author who is a faculty member of Seijo University, Japan. Seijo’s Glocal Research Center is also supported by the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology.

In his concluding remarks of the study, the author wrote:

I became interested in Hawai‘i’s status as an occupied country through an earlier interest in the struggle of Okinawans to have US military bases removed from their territory. I naively thought, like many in Japan, that the US should move these military operations back to Hawai‘i because they rightly belong on American territory. Yet as I compared the two places, I learned that under international law Hawai‘i actually had a stronger claim than Okinawa on the right to reject an American military presence. Unfortunately, Okinawa never had foreign treaties and recognition as an independent state before it was absorbed by Japan. This leaves Okinawa to fight for self-determination through a political negotiation with the Japanese government, and the Japanese government is very committed to its alliance with America. Although Prime Minister Shinzo Abe stated in his speech of August 15, 2015, “We shall abandon colonial rule forever and respect the right of self-determination of all peoples throughout the world,” it is unlikely that he had Okinawans in mind, or anyone specifically, as a people he would assist in becoming independent.

During the interview, as a spokesperson for the provisional government, Professor Sai was careful not to discuss the policy or ideology that a future legitimate government would follow. Those are to be decided by democratic choices that Hawaiians make after the occupation ends. However, it was encouraging to hear Professor Sai, a former US Army captain, express a strong personal view that Hawai‘i’s record as a neutral country is not something that should be up for future debate. It’s a fundamental value that makes the work to restore the nation worthwhile, and it is something that can inspire the global community as well.

There is an increasing global desire for America to scale back its interventionism and close its global network of military bases. The day has come when the world doesn’t want it, and America can no longer afford it. It is ironic that a place that everyone thinks is American is the place that has the strongest chance of using international law to expel the American military presence. Other nations are bound by their treaties and Status of Forces Agreements. It is also inspiring too to think that this will happen in the place that was the last place on the globe to be inhabited by humans, and the last to be contacted by the European explorers who launched the age of Western Empire.

Today, Western science turns its back on earthly problems as it tries to build telescopes and train astronauts to Mars-walk on Hawaiian mountains, but for those who prefer to deal with the home we have, Hawai‘i can be a symbol of our last hope to avoid the catastrophes of environmental destruction and war, just as it was a last hope for the Polynesian explorers who first came in the years of the early Christian calendar—an interesting coincidence considering the peaceful aspirations of Christianity that preceded the meeting of two cultures in Hawai‘i in the 18th century. Now that Japan has reinterpreted its “peace” constitution to allow for overseas deployments in assistance of allies, the world should support Hawai‘i not only for the sake of self-interested realism but more importantly for the role Hawai‘i can play as a new standard bearer of the idea that nations can renounce war, choose neutrality and gain security from a system of international law that protects their sovereignty.

There is still much confusion regarding the terms sovereignty and independence in the Hawaiian community, which is the result of denationalization through Americanization. First there are two sovereignties – “internal” and “external.” By definition, sovereignty is the supreme governmental authority over the territory of a State. Where a particular State may have “internal” sovereignty over its territory, it may not have “external sovereignty” regarding its place as a State in international law. An example of this is the State of New York, which has “internal” sovereignty over its territory, but its “external” sovereignty is in the United States of America. It is the United States, and not New York, that is the independent State.

Because international law distinguishes between “internal” and “external” sovereignties, a State would remain independent and sovereign, despite its government, which exercises its internal sovereignty, having been overthrown by another State and subsequently occupied. This is why the law of occupation mandates the occupier to administer the laws of the occupied State under Article 43 of the 1907 Hague Convention, IV.

Section 358 of the United States Army Field Manual 27-10 clearly articulates this point, where “military occupation confers upon the invading force the means of exercising control for the period of occupation. It does not transfer the sovereignty to the occupant, but simply the authority or power to exercise some of the rights of sovereignty.”

Below is an article that was originally posted December 10, 2013

In Hawai‘i there is a political trend called the sovereignty or independence movement that began in the 1970s. This political wing, which grew out of the Hawaiian cultural renaissance movement, is comprised of diverse groups of aboriginal Hawaiians working toward the goal or aspiration of achieving sovereignty or independence. These groups vary in ideologies and organization, but all of them have been operating on the false assumption that the United States has independence and sovereignty over Hawai‘i and therefore the goal is separation or secession through a process commonly referred to as self-determination. According to the United Nations, self-determination is the right of the people of a non-sovereign nation to choose their own form of governance separate from the foreign State that has the sovereignty and independence under international law.

Actions taken by these groups are centered on political activism that have taken many forms at both the national and international levels. This political trend has led to confusion regarding Hawai‘i’s true status and basic terminology and the application of the terms “sovereignty” and “independence.” Also adding to the confusion is the psychological effects of “presentism” and “confirmation bias.” Presentism is “an attitude toward the past dominated by present-day attitudes and experience,” and confirmation bias is “a tendency to search for or interpret information in a way that confirms one’s preconceptions, leading to statistical errors.”

Sovereignty by definition is absolute authority exercised by a State over its territory, territorial seas, and its nationals abroad, which is independent of other States and their authority over their territory, territorial seas, and its nationals abroad. Authority over a State’s nationals abroad is called personal supremacy, and authority over territory is territorial sovereignty. Therefore, sovereignty is associated with political independence and the terms are often interchangeable.

The term State, under international law, means a political unit that has a centralized government, a resident population, a defined territory and the ability to enter and maintain international relations with other States. A State is a legal person in international law that possesses rights and obligations. A nation, however, is a group of people bound together by a common history, language and culture. Every State is a nation or a combination of nations, but not every nation or nations comprise a State. Since the nineteenth century, a State comes into existence only if other States have recognized it, which represents the entirety of the international order. In other words, a few States may have given explicit recognition, but the majority hasn’t. Until the majority of States have provided recognition to the nation or group of nations, international law does not recognize the new State because its independence over its territory, territorial seas, and its nationals abroad has not been acknowledged by the international community of States.

The most recent example of a sovereignty movement by a nation seeking State sovereignty and independence and ultimately achieving it was Palestine. On November 29, 2012, the member States of the United Nations voted overwhelmingly to recognize Palestinian Statehood. Up to this date, Palestine was a nation seeking sovereignty and independence, which is called self-determination. Once a State has been recognized the recognizing States cannot deny it later, and there exists a rule of international law that preserves the independence of an already recognized State, unless that State has relinquished its independence and sovereignty by way of a treaty or customary practice recognized by international law.

According to the Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ), in the 1927 seminal case S.S. Lotus between France and Turkey, “International law governs relations between independent States. The rules of law binding upon States therefore emanate from their own free will as expressed in conventions (treaties) or by usages generally accepted as expressing principles of law and established in order to regulate the relations between these co-existing independent communities or with a view to the achievement of common aims. Restrictions upon the independence of States cannot therefore be presumed.” In other words, once a State is acknowledged as being independent it will continue to be independent unless proven otherwise. Therefore, the State will still have sovereignty and independence over its territory, territorial seas, and its nationals, even when its government has been overthrown and is militarily occupied by a foreign State. During occupations the sovereignty remains vested in the occupied State, but the authority to exercise that sovereignty is temporarily vested in the occupying State, which is regulated by the Hague and Geneva Conventions, and international humanitarian law.

When the PCIJ stated that restrictions upon the independence of States could not be presumed, it did not mean that international law could not restrict States in its relations with other States that are also independent. In the Lotus case, the PCIJ explained, “Now the first and foremost restriction imposed by international law upon a State is that—failing the existence of a permissive rule to the contrary—it may not exercise its power in any form in the territory of another State. In this sense jurisdiction is certainly territorial; it cannot be exercised by a State outside its territory except by virtue of a permissive rule derived from international custom or from convention (treaty).” The PCIJ continued, “In these circumstances, all that can be required of a State is that it should not overstep the limits which international law places upon its jurisdiction; within these limits, its title to exercise jurisdiction rests in its sovereignty.”

The United States Supreme Court in 1936 recognized this restriction and limitation of a State’s authority in international law in U.S. v. Curtiss-Wright Corp. The U.S. Supreme Court stated, “Neither the Constitution nor the laws passed in pursuance of it have any force in foreign territory unless in respect of our own citizens…, and operations of the nation in such territory must be governed by treaties, international understandings and compacts, and the principles of international law. As a member of the family of nations, the right and power of the United States in that field are equal to the right and power of the other members of the international family. Otherwise, the United States is not completely sovereign.”

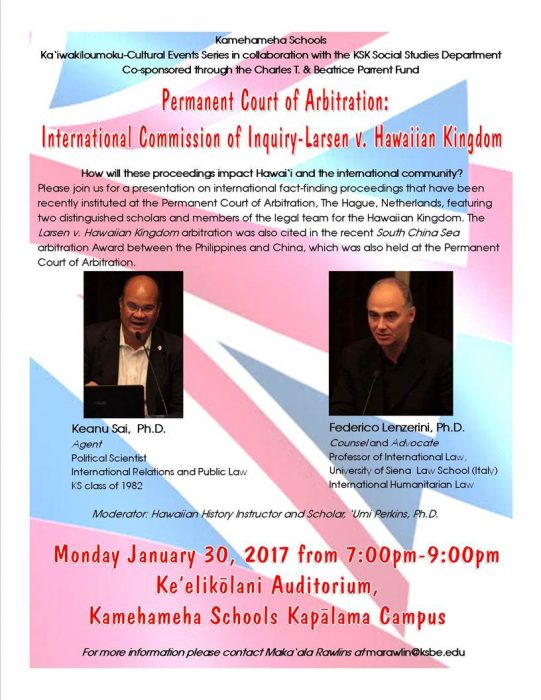

In 2001, the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA), in its dictum in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, verified Hawai‘i to be an independent State. In its arbitral award, the PCA stated, “in the nineteenth century the Hawaiian Kingdom existed as an independent State recognized as such by the United States of America, the United Kingdom and various other States, including by exchanges of diplomatic or consular representatives and the conclusion of treaties.” As an independent State, international law provided a fundamental restriction on all States, to include the United States of America, that it may “not exercise its power in any form in the territory of another State.”

Since 1898, the United States has unlawfully exercised its power within the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom militarily, legislatively and economically. On July 7, 1898, the United States Congress enacted a joint resolution unilaterally annexing the Hawaiian Kingdom over the protests of Hawai‘i’s Queen and people. Two years later, Congress enacted another law by creating a territorial government that took over the governmental infrastructure of the Hawaiian Kingdom that was previously high jacked by insurgents since 1893 with the support of the United States military. In 1959, the Congress again passed legislation transforming the territorial government into the 50th state of the American Union. Under both international law and United States constitutional law, these Congressional actions have no force and effect in Hawai‘i. Despite the propaganda and lies that have been perpetuated since the beginning of the occupation that Hawai‘i was annexed by a treaty, the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to be an independent State that still retains its personal supremacy over its nationals abroad, and territorial sovereignty over its territory and territorial seas. The exercising of this authority, however, is limited only by the Hague and Geneva Conventions and the fact of an illegal and prolonged occupation.

A common statement made by sovereignty advocates is that the people have to collectively decide on the question of sovereignty and that it should be put to a vote. This is incorrect if Hawai‘i is already a sovereign and independent State. This prospect is valid only if Hawai‘i is a nation seeking sovereignty and independence, which is commonly referred to as “nation-building” under a people’s right to self-determination, but Hawai‘i is not. Self-determination and nation-building is the United Nations process by which sovereignty and independence is sought, but it is not guaranteed. This process provides to the people of a non-sovereign nation who have been colonized by a foreign State to choose whether or not they want independence from the foreign State, free association as an independent State with the foreign State, or total incorporation into the foreign State.

Recently, Maohi Nui (French Polynesia) has been reaffirmed by the United Nations as having a right to choose independence from France, free association with France, or total incorporation into France. Maohi Nui is by definition a sovereignty movement and education is key to ensuring that the people decide Maohi Nui’s status through decolonization with full knowledge, and not be influenced or coerced by political activism that is French driven. It won’t be easy for Maohi Nui, but the process of exercising self-determination should be fair under United Nations supervision and in line with General Assembly resolutions.

If other independent States cannot affect or change the independence of an established State and its sovereignty under international law, how can Hawai‘i’s people believe they can do what States can’t? Because the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist under international law as an independent State, not only is the sovereignty movement rendered irrelevant, but also the status of Hawai‘i as an occupied State renders the State of Hawai‘i government and other federal agencies in the Hawaiian Islands self-proclaimed. It is within this international legal framework that actions taken by Federal government officials, State of Hawai‘i government officials, and County government officials are being reported to international authorities for war crimes under the Hague and Geneva Conventions, and the Rome Statute that established the International Criminal Court.

Re-education is crucial for Hawai‘i’s people and the world on the reality that Hawai‘i is an already independent and sovereign State that has been under an illegal and prolonged occupation. Before restoration of the de jure Hawaiian government takes place in accordance with the 1893 executive agreements, international law mandates that the occupying Power must establish a military government in order to administer Hawaiian Kingdom law (Article 43, Hague Convention, IV) and to also begin the withdrawal of all military installations from Hawaiian territory (Article 2, Hague Convention, V). This is the first and primary step toward transition.

The following terms and definitions are from the Hawaiian history textbook “Ua Mau Ke Ea-Sovereignty Endures.”

Independent State—A state that has absolute and independent legal and political authority over its territory to the exclusion of other states. Once recognized as independent, the state becomes a subject of international law. According to United States common law, an independent State is a people permanently occupying a fixed territory bound together by common law habits and custom into one body politic exercising, through the medium of an organized government, independent sovereignty and control over all persons and things within its boundaries, capable of making war and peace and of entering into international relations with other communities around the globe.

Sovereignty—Supreme authority exercised over a particular territory. In international law, it is the supreme and absolute authority exercised through a government, being independent of any other sovereignty. Sovereignty, being authority, is distinct from government, which is the physical body that exercises the authority. Therefore, a government can be overthrown, but the sovereignty remains.

Colonization—Colonization is the building and maintaining of colonies in one territory by people from another country or state. It is the process, by which sovereignty over the territory of a colony is claimed by the mother country or state, and is exercised and controlled by the nationals of the colonizing country or state. Though colonization there is an unequal relationship between the colonizer and the native populations that reside within its colonial territory. These native populations are referred to as indigenous peoples and form the basis of the 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

De-colonization—De-colonization is the political process by which a non-self-governing territory under the sovereignty of the colonizing state or country becomes self-governing. According to the United Nations Resolution 1541 (XV), Principles which should guide Members in determining whether or not an obligation exists to transmit the information called for under Article 73 e of the Charter, “A Non-Self-Governing Territory can be said to have reached a full measure of self government by: (a) Emergence as a sovereign independent State; (b) Free association with an independent State; or (c) Integration with an independent State.”

Self-determination—A principle in international law that nations have the right to freely determine their political status and pursue their economic, social and cultural development. The international community first used the term after World War I where the former territorial possessions of the Ottoman Empire and Germany were assigned to individual member countries or states of the League of Nations for administration as Mandate territories. The function of the administration of these territories was to facilitate the process of self-determination whereby these territories would achieve full recognition as an independent and sovereign state. After World War II, territories of Japan and Italy were added and assigned to be administered individual member countries or states of the United Nations, being the successor of the League of Nations, and were called Trust territories. Also added to these territories were territories held by all other members of the United Nations and called Non-self-governing territories. Unlike the Mandate and Trust territories, they were not assigned to other member countries or states for administration, but remained under the original colonial authority who reported yearly to the United Nations on the status of these territories. Self-determination for Non-self-governing territories had three options: total incorporation into the colonial country or state, free association with the colonial country or state, or complete independence from the colonial country or state. Self-determination for indigenous peoples does not include independence and is often referred to as self-determination within the country or state they reside in.

Sovereignty movement—A political movement of a wide range of groups in the Hawaiian Islands that seek to exercise self-determination under international law as a Non-self-governing unit, or to exercise internal self-determination under the 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The commonality of these various groups is that their political platforms are based on aboriginal Hawaiian identity and culture and use of the United Nations term indigenous people. The movement presumes that the Hawaiian Kingdom and its sovereignty were overthrown by the United States January 17th 1893, and therefore the movement is seeking to reclaim that sovereignty through de-colonization. The movement does not operate on the presumption of continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent state and the law of occupation, but rather on the aspiration of becoming an independent state or some form of internal self-determination within the laws of the United States.

https://vimeo.com/192878178

Dr. Lynette Cruz, host of “Issues that Matter,” interviews Dr. Keanu Sai on recent trip to Italy. Dr. Sai was invited to participate in an academic conference in Ravenna, Italy, as well as guest lectures as the University of Siena Law School and at the University of Torino.

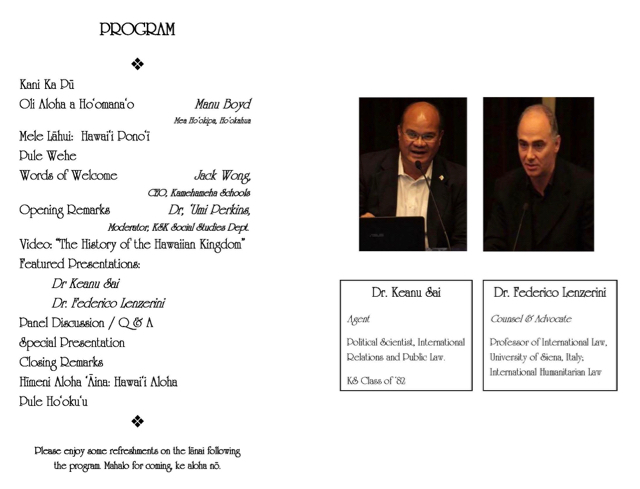

My name is Dr. David Keanu Sai and from 1999-2001, I served as Agent for the Hawaiian Kingdom in international arbitration proceedings under the auspices of the Permanent Court of Arbitration, The Hague, Netherlands. The case was Lance Paul Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom (Larsen case). I was responsible for the drafting of the pleadings as well as communication with the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s (PCA) International Bureau-Secretariat, headed by a Secretary General, regarding the case. So I am very well acquainted with the case as well as what was going on behind the formalities of the case and the confines of the published Award in the International Law Reports, vol. 119, p. 566.

My name is Dr. David Keanu Sai and from 1999-2001, I served as Agent for the Hawaiian Kingdom in international arbitration proceedings under the auspices of the Permanent Court of Arbitration, The Hague, Netherlands. The case was Lance Paul Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom (Larsen case). I was responsible for the drafting of the pleadings as well as communication with the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s (PCA) International Bureau-Secretariat, headed by a Secretary General, regarding the case. So I am very well acquainted with the case as well as what was going on behind the formalities of the case and the confines of the published Award in the International Law Reports, vol. 119, p. 566.

I am also a lecturer at the University of Hawai‘i with a M.A. and a Ph.D. in political science specializing in international relations and public law. My doctoral research and published law articles centers on the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State under a prolonged occupation by the United States of America (United States) since the Spanish-American War.

After reviewing the two Awards by the Tribunal in the South China Sea case, I perused the Philippines’ Memorial and transcripts of the proceedings to find any reference to the Larsen case that was cited in Tribunal’s Award on Jurisdiction and Admissibility (paragraph 181) as well as the Award on the Merits (paragraph 157, footnote 98). In the Memorial, which is called a pleading in international proceedings, the Philippines brought up the Larsen case in paragraphs 5.125 and 5.126. It was also mentioned by Professor Philippe Sands, QC, in his expert testimony to the Tribunal during a hearing on jurisdiction on July 8, 2015, and found on page 123 of the transcripts. On the Larsen case, the Philippine Memorial stated:

5.125 The Monetary Gold principle has also been followed once in arbitral proceedings. An arbitral tribunal applied it propio motu in Larsen v. the Hawaiian Kingdom. In that case, a resident of Hawaii sought redress from “the Hawaiian Kingdom” for its failure to protect him from the United States and the State of Hawaii. The parties, who had agreed to submit their dispute to arbitration by the PCA, hoped that the tribunal would address the question of the international legal status of Hawaii. Both parties initially argued that the Monetary Gold principle should be confined to ICJ proceedings. The tribunal rejected that argument, stating that international arbitral tribunals “operate[ ]within the general confines of public international law and, like the International Court, cannot exercise jurisdiction over a State which is not a party to its proceedings”.

5.126 The tribunal ultimately decided that it was precluded from addressing the merits because the United States, which was absent, was an indispensable party. Relying on Monetary Gold, the tribunal explained that the legal interests of the United States would form “the very subject-matter” of a decision on the merits because it could not rule on the lawfulness of the conduct of the respondent, the Kingdom of Hawaii, without necessarily evaluating the lawfulness of the conduct of the United States. It emphasized that “[t]he principle of consent in international law would be violated if this Tribunal were to make a decision at the core of which was a determination of the legality or illegality of the conduct of a non-party”.

There is much said in these two paragraphs that may escape the layman who may not be familiar with Hawai‘i’s legal history and its place in international law. By the Philippines own admission it recognized the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a party to the arbitration, and without the participation of the United States, as an indispensable third party, the Philippines stated the Larsen Tribunal “could not rule on the lawfulness of the conduct of the respondent, the Kingdom of Hawaii.”

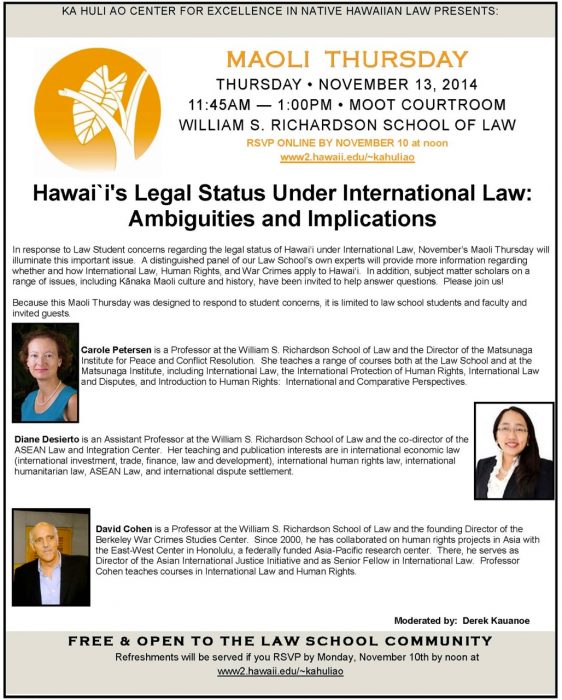

Here at the University of Hawai‘i William S. Richardson School of Law, a few faculty members, namely Dr. Diane Desierto, Dr. David Cohen, and Carol Peterson, have gone so far as to call the Larsen case mere puffery. But can the Larsen case be an exaggeration of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s continued existence under international law and the role of the principle of indispensable third parties when it comes to the United States, as claimed by these faculty members who admitted, at a closed forum, they don’t know the legal history of Hawai‘i?

Obviously, the Philippine Government did not think so, and nor did the Tribunal in the South China Sea arbitration. As a landmark case in international arbitration, the South China Sea arbitration has drawn attention to the Larsen case again, which gives me an opportunity to set the record straight in light of the detractors, but also for those who are just curious.

In the Larsen case, the Hawaiian Kingdom, which I served as Agent along with others on my legal team, was a “Defendant,” which in international proceedings is also called a “Respondent.” This means that the Hawaiian Kingdom was defending itself from the allegations made by Larsen, as the “Plaintiff,” which is also called a “Claimant,” that the Council of Regency was allowing the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws in the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom, which led to his unfair trial and subsequent incarceration.

By going to Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom at the PCA’s case repository, it identifies me as the Agent for the Hawaiian Kingdom, identifies the Hawaiian Kingdom as a “State,” and under the heading of “case description,” it provides the dispute as follows:

“Dispute between Lance Paul Larsen (Claimant) and The Hawaiian Kingdom (Respondent) whereby

The Philippines’ Memorial also cites an article by Bederman and Hilbert on the Larsen case that was originally published in the American Journal of International (vol. 95, p. 928), and republished the article in the Hawaiian Journal of Law and Politics (vol. 1, p. 82) that the Philippines cited. According to Bederman and Hilbert, who succinctly stated the dispute, “At the center of the PCA proceeding was…that the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist and that the Hawaiian Council of Regency (representing the Hawaiian Kingdom) is legally responsible under international law for the protection of Hawaiian subjects, including the claimant. In other words, the Hawaiian Kingdom was legally obligated to protect Larsen from the United States’ ‘unlawful imposition [over him] of [its] municipal laws’ through its political subdivision, the State of Hawaii. As a result of this responsibility, Larsen submitted, the Hawaiian Council of Regency should be liable for any international law violations that the United States committed against him.”

Clearly, the Larsen case was not about whether the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist, but was based on the presumption that it does exist, and, as such, a dispute arose between a Hawaiian national and the Hawaiian Government that stemmed from an illegal and prolonged occupation by the United States. My responsibility, as the Agent, was to defend the Hawaiian Government from Larsen’s allegation of allowing the imposition of American municipal laws in the Hawaiian Islands.

I was also keenly aware that before the PCA could establish the Arbitral Tribunal to preside over the dispute between Larsen and the Hawaiian Kingdom, it had to first confirm that the Hawaiian Kingdom as a “State” continues to exist in order for the PCA to exercise its “institutional jurisdiction” (United Nations Dispute Settlement, Permanent Court of Arbitration, p. 15) so that it could facilitate the creation of an ad hoc tribunal. By extension, the PCA also had to confirm that Larsen’s nationality was a Hawaiian subject, and the Council of Regency was the Hawaiian Government.

As an intergovernmental organization established under the 1899 Hague Convention, I, and the 1907 Hague Convention, I, the PCA facilitates the creation of ad hoc arbitral tribunals to settle disputes between two or more States, i.e., the Philippines v. China, or between a State and a private entity, i.e., Romak, S.A. v. Uzbekistan. Romak, S.A. is a Swiss company that specializes in the sale of grain and cereal products. In both cases, the States have to exist in fact and not in theory in order for the PCA to have institutional jurisdiction. Disputes must be “international” and not “municipal,” which are disputes that go before national courts of States and not international courts or tribunals.

Since the arbitration agreement between Larsen and the Hawaiian Government was submitted to the PCA on November 8, 1999, the PCA was doing their due diligence as to whether the Hawaiian Kingdom currently exists as a State under international law. If the Hawaiian Kingdom does not exist then this fact would negate the existence of the nationality of Larsen as a Hawaiian subject and the existence of the Council of Regency as the Hawaiian government, and, therefore, the dispute.

After its due diligence, however, the PCA could not deny that the Hawaiian Kingdom did exist as an independent State, and, along with other treaties, the Hawaiian Kingdom had a treaty with the Netherlands, which houses the PCA itself. However, what faced the PCA is that it could not find any evidence that the Hawaiian Kingdom had ceased to exist under international law. Only by way of a “treaty of cession,” whereby the Hawaiian Kingdom agreed to merge itself into the territory of the United States, could the Hawaiian Kingdom have been extinguished under international law.

There was never a treaty, except for American municipal laws, enacted by the United States Congress, that treat Hawai‘i as if it were annexed. Municipal laws are not international laws, as between States, but are laws that are limited in scope and authority to the territory of the State that enacted them. In other words, an American municipal law could no more annex the Hawaiian Kingdom, than it could annex the Netherlands.

My legal team and Larsen’s attorney knew this and operated on the “presumption” that the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist until evidence shows otherwise. This was the  same conclusion that the PCA came to, which prompted a telephone conversation I had with the PCA’s Secretary General, Tjaco T. van den Hout, in February 2000. In that telephone conversation, he recommended that the Hawaiian Government along with Larsen’s Counsel, Ms. Ninia Parks, provide a formal invitation to the United States Government to join in the arbitration. I recall his specific words to me on this matter. He said that in order to maintain the integrity of this case, he recommended that the Hawaiian Government, with the consent of Larsen’s legal representative, provide a formal invitation to the United States to join in the current arbitration. He then requested that I provide evidence that the invitation was made so that it can be made a part of the record for the case.

same conclusion that the PCA came to, which prompted a telephone conversation I had with the PCA’s Secretary General, Tjaco T. van den Hout, in February 2000. In that telephone conversation, he recommended that the Hawaiian Government along with Larsen’s Counsel, Ms. Ninia Parks, provide a formal invitation to the United States Government to join in the arbitration. I recall his specific words to me on this matter. He said that in order to maintain the integrity of this case, he recommended that the Hawaiian Government, with the consent of Larsen’s legal representative, provide a formal invitation to the United States to join in the current arbitration. He then requested that I provide evidence that the invitation was made so that it can be made a part of the record for the case.

This invitation would elicit one of the three possible responses: first, the United States accepts the invitation, which recognizes the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom and its government and will have to answer to its unlawful imposition of American municipal laws that led to Larsen’s unfair trial and incarceration; second, the United States denies the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom because Hawai‘i is the so-called 50th State of the Federal Union and demands that the PCA cease and desist in entertaining the dispute; or, third, the United States denies the invitation to join in the arbitration but does not deny the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the dispute between a Hawaiian national and the government representing the Hawaiian Kingdom.

On March 3, 2000, a conference call meeting was held with John Crook from the United States State Department in Washington, D.C., together with myself representing the Hawaiian Government and Ms. Parks representing Larsen. After the meeting, I drafted a letter to Crook that covered what was discussed in the meeting regarding the invitation and a carbon copy was sent to Secretary General van den Hout, as he requested, so that it could be placed on the record that an invitation was made. A few days later the United States Embassy in The Hague notified the PCA that they denied the invitation to join in the  arbitration, but requested permission from the Hawaiian Government and Ms. Parks, on behalf of Larsen, to have access to all pleadings and transcripts of the case. Both Ms. Parks and I were individually contacted by telephone from the PCA’s Deputy Secretary General, Phyllis Hamilton, of the request made by the US Embassy, which we both consented to. It was also agreed that the records of the proceedings would be open to the public.

arbitration, but requested permission from the Hawaiian Government and Ms. Parks, on behalf of Larsen, to have access to all pleadings and transcripts of the case. Both Ms. Parks and I were individually contacted by telephone from the PCA’s Deputy Secretary General, Phyllis Hamilton, of the request made by the US Embassy, which we both consented to. It was also agreed that the records of the proceedings would be open to the public.

The United States took the third option and did not deny the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Thereafter, the PCA began to form the Arbitral Tribunal the following month in April of 2000. Memorials were filed with the Tribunal by Larsen on May 22, 2000, and the Hawaiian Government on May 25, 2000. The Hawaiian Government then filed its Counter-Memorial on June 22, 2000, and Larsen its Counter-Memorial on June 23, 2000.

After the pleadings were submitted, the Tribunal issued Procedural Order no. 3 on July 17, 2000. In the Procedural Order, the Tribunal articulated the dispute from the pleadings in the following statement.

The Tribunal further stated in the Procedural Order that it “is concerned whether the first issue does in fact raise a dispute between the parties, or, rather, a dispute between each of the parties and the United States over the treatment of the plaintiff by the United States. If it is the latter, that would appear to be a dispute which the Tribunal cannot determine, inter alia because the United States is not a party to the agreement to arbitrate.” The Tribunal, therefore, stated that it could not get to the merits of the case regarding “redress against the Respondent Government” as the second issue, until it address the first issue that Larsen’s “rights as a Hawaiian subject are being violated…by the United States of America.” This first issue that the Tribunal was asked to determine is what caused the Tribunal to raise the principle of an “indispensable third party” that stemmed from the Monetary Gold case. In other words, could the Tribunal proceed to rule on the lawfulness of the conduct of the Hawaiian Government when its judgment would imply an evaluation of the lawfulness of the conduct of the United States, which is not a party to the case.

The Tribunal scheduled oral hearings to be held at the PCA on December 7, 8 and 11, 2000.

https://vimeo.com/17007826

A day before the oral hearings were to begin on December 7, the three arbitrators met with myself and legal team and Ms. Parks in the PCA to go over the schedule and what we can expect. What they also provided to us were booklets of the decisions by the International Court of Justice, namely the Monetary Gold Removed from Rome in 1943 (Italy v. the United Kingdom, France and the United States), Case Concerning Certain Phosphate Land in Nauru (Nauru v. Australia), and Case Concerning East Timor (Portugal v. Australia).

All three cases centered on the indispensable third party principle and that we should be prepared to respond as to how this case can proceed without the participation of the United States. In the Monetary Gold case it was on the non-participation of Albania; the Nauru Case was the non-participation of New Zealand and the United Kingdom; and the East Timor case was the non-participation of Indonesia. Of the three cases, only the Nauru case could proceed because the ICJ concluded that New Zealand and the United Kingdom were not indispensable third parties.

After two days of hearings, it was evident that the Tribunal would not be able to adjudge and declare, according to Procedural Order no. 3, that Larsen’s “rights as a Hawaiian subject are being violated…by the United States of America,” because the United States was not a party to the proceedings. Without a decision by the Tribunal that finds Larsen’s rights are being violated, he would be unable to get to the second issue of having the Tribunal declare and adjudge that he “does have ‘redress against the Respondent Government’ in relation to these violations.” In light of this, I knew that Larsen would not prevail in these proceedings without the participation of the United States. On the final day of the hearings, December 11, I decided to ask the Tribunal to make a determination on a topic that I felt would not violate the indispensable third party principle that was at the center of these proceedings.

The Hawaiian Government needed a pronouncement by the Tribunal as to the legal status of the Hawaiian Kingdom under international law that would deny the lawfulness of American municipal laws within Hawaiian territory. In other words, the Hawaiian Government needed a pronouncement of international law that could be cited as a bar to American municipal laws from being applied in Hawaiian territory. This fundamental bar of one State’s municipal laws to be applied within the territory of another State centers on the legal meaning of “independence.”

In international arbitration between the Netherlands and the United States at the PCA (Island of Palmas case), the arbitrator explained what the term independence means in  international law. In the Award (p. 8), Judge Max Huber stated, “Sovereignty in the relations between States signifies independence. Independence in regard to a portion of the globe is the right to exercise therein, to the exclusion of any other State, the functions of a State. The development of the national organization of State during the last few centuries and, as a corollary, the development of international law, have established this principle of the exclusive competence of the State in regard to its own territory.”

international law. In the Award (p. 8), Judge Max Huber stated, “Sovereignty in the relations between States signifies independence. Independence in regard to a portion of the globe is the right to exercise therein, to the exclusion of any other State, the functions of a State. The development of the national organization of State during the last few centuries and, as a corollary, the development of international law, have established this principle of the exclusive competence of the State in regard to its own territory.”

Oppenheim, International Law, Vol. 1, p. 177-8 (2nd ed. 1912), explains: “Sovereignty as supreme authority, which is independent of any other earthly authority, may be said to have different aspects. As excluding dependence from any other authority, and in especial from the authority of the another State, sovereignty is independence. It is external independence with regard to the liberty of action outside its borders in the intercourse with other States which a State enjoys. It is internal independence with regard to the liberty of action of a State inside its borders. As comprising the power of a State to exercise supreme authority over all persons and things within its territory, sovereignty is territorial supremacy. As comprising the power of a State to exercise supreme authority over its citizens at home and abroad, sovereignty is personal supremacy. For these reasons a State as an International Person possesses independence and territorial and personal supremacy.”

With this in mind, I made the following statement and request to the Tribunal that is provided in the transcripts of the final day of the hearings on December 11.

The issue before the Tribunal was whether Larsen could hold to account the Hawaiian Government for allowing the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws within Hawaiian territory that led to his unfair trial and subsequent incarceration. My request of the Tribunal on the last day of the oral hearings was to have the Tribunal acknowledge and pronounce the legal status of Hawai‘i under international law as an “independent State,” which, as a co-equal, the United States could not impose its municipal laws within Hawaiian territory without violating international law.

My intent, was to move beyond the dispute with Larsen and address the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws across the entire territory of Hawai‘i and everyone affected by it, not just Larsen. I understood that my request of the Tribunal would not violate the indispensable third party principle, because for the Tribunal to make this pronouncement there would be no need to address the lawfulness or unlawfulness of the conduct of the United States, but merely to acknowledge historical facts.

My request of the Tribunal was similar to the Philippines request of the South China Sea Tribunal to determine whether or not the landmasses in the South China Sea are islands or rocks. The Philippines argued that since it is merely a determination of facts, the Tribunal would not be getting into the lawfulness or unlawfulness of the conduct of States regarding the sovereignty over these islands. The sovereign claims over these land masses would be whether the land masses are islands as defined under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea that establish a maritime zone, or are they rocks that would not establish the maritime zones. According to Article 121(3) of the Convention, an island must “sustain human habitation or economic life of [its] own” in order to generate maritime zones, i.e., the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of 200 miles from its coast. This is how the Philippines successfully argued why the principle of indispensable third parties would not apply.

On February 5, 2001, the Tribunal issued the Award on Jurisdiction, and concluded that the United States was an indispensable third party. In paragraph 12.5, the Tribunal explained, “It follows that the Tribunal cannot determine whether the [Hawaiian Kingdom] has failed to discharge its obligation towards [Lance Larsen] without ruling on the legality of the acts of the United States of America. Yet that is precisely what the Monetary Gold principle precludes the Tribunal from doing. As the International Court of Justice explained in the East Timor case, ‘the Court could not rule on the lawfulness of the conduct of a State when its judgment would imply an evaluation of the lawfulness of the conduct of another State which is not a party to the case.’”

The Tribunal, however, did answer my request, which is provided in paragraph 7.4 of the Award. The Tribunal stated, “A perusal of the material discloses that in the nineteenth century the Hawaiian Kingdom existed as an independent State recognised as such by the United States of America, the United Kingdom and various other States, including by exchanges of diplomatic or consular representatives and the conclusion of treaties.” By using the phrase, “a perusal of the material,” the Tribunal made it clear that its conclusion that the United States recognized the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State was drawn from the facts of the case.

By declaring that the United States recognized “the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State,” is another way of stating that the United States recognized that only Hawaiian laws could be applied in Hawaiian territory and not the municipal laws of the United States. Through these international proceedings, the Hawaiian Government was able to broaden the impact of an unlawful occupation beyond the Larsen case to now include all persons that have been victimized by the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws within the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

The Award of the South China Sea arbitration’s reference of the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom is recognition of the integrity of the Larsen case itself and why it is now a precedent case regarding the principle of indispensable third parties along with the Monetary Gold case and the East Timor case. It is also an acknowledgment of the caliber of those individuals who served as arbitrators, two of which are now serving as Judges on the International Court of Justice, namely Judge Christopher Greenwood and Judge James Crawford, who served as President of the Tribunal.

When I entered the University of Hawai‘i Political Science Department to get my M.A. and Ph.D. I also planned to address the misinformation regarding Hawai‘i as the 50th State of the American Union and the categorization of native Hawaiians as indigenous people as defined under United Nations documents. This is a false narrative that has already been rebuked by the mere fact of the Larsen case, which has now become a precedent case in international law. This information about the Hawaiian Kingdom has made people very uncomfortable, but that’s what happens when you’re faced with the truth.

The recent South China Sea arbitration, being a landmark case, has cited the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom case as one of the international precedents on “indispensable third parties” along with the Monetary Gold Removed from Rome in 1943 case and East Timor case in its Arbitral Award on Jurisdiction and Admissibility (paragraph 181). This is a significant achievement for the Hawaiian Kingdom in international law.

On July 12, 2016, the Arbitral Tribunal in the South China Sea Arbitration (The Republic of the Philippines v. the People’s Republic of China), established under the auspices of the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA), issued its decision in The Hague, Netherlands. The decision found that China’s claims over manmade islands in the South China Sea have no legal basis. Its decision was based on the definition of an “island” under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (1982) (Convention).

According to Article 121(3) of the Convention, an island must “sustain human habitation or economic life of [its] own” in order to generate maritime zones, i.e., the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of 200 miles from its coast. Therefore, China’s creation of islands were never islands to begin with but rather reefs or rocks, which precluded China from claiming any maritime zones. For background of the dispute visit the New York Times “Philippines v. China, Q. and A. on South China Sea.”

At first glance, it would appear that China contested the jurisdiction of the Arbitral Tribunal in a Position Paper it drafted on December 7, 2014, and on this basis refused to participate in the proceedings held at the PCA in The Hague, Netherlands. So how is it possible that the Arbitral Tribunal pronounces a ruling against China when it hasn’t participated in the arbitration?

The simple answer is that the Arbitral Tribunal could issue a ruling because China “did” participate in the proceedings and has consented to PCA’s authority to establish the Tribunal by virtue of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (1982). As noted in the PCA’s press release, the PCA currently has 12 other cases established under Annex VII of the Law of the Sea Convention. China is a State party to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, and arbitration is recognized as a means to settle disputes under Annex VII.

As a State party to the Convention, China consented to arbitration even if it chose not to participate, but it did signify its participation when it made its position public regarding the arbitration proceedings. According to the Arbitral Tribunal in its Arbitral Award on Jurisdiction and Admissibility, it stated in paragraph 11, “the non-participation of China does not bar this Tribunal from proceeding with the arbitration. China is still a party to the arbitration, and pursuant to the terms of Article 296(1) of the Convention and Article 11 of the Annex VII, it shall be bound by any award the Tribunal issues.”

What is not commonly understood is that there are two matters of jurisdiction in cases that come before the PCA. The first is “institutional jurisdiction” of the PCA, and the second is “subject matter jurisdiction” of the Arbitral Tribunal over the particular dispute.

As an intergovernmental organization established under the 1899 Hague Convention, I, and the 1907 Hague Convention, I, the PCA facilitates the creation of ad hoc Arbitral Tribunals to settle disputes between two or more States (interstate), between a State and an international organization, between two or more international organizations, between a State and a private entity, or between an international organization and a private entity (United Nations Dispute Settlement, Permanent Court of Arbitration, p. 15). Disputes must be “international” and not “municipal,” which are disputes that go before national courts of States and not international courts or tribunals.

An explanation of the PCA’s institutional jurisdiction is also provided in the South China Sea case press release. On page 3 the press release the PCA states, “The Permanent Court of Arbitration is an intergovernmental organization established by the 1899 Hague Convention on the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes. The PCA has 121 Members States. Headquartered at the Peace Palace in The Hague, the Netherlands, the PCA facilitates arbitration, conciliation, fact-finding, and other dispute resolution proceedings among various combinations of States, State entities, intergovernmental organizations, and private parties.” China became a member State of the PCA on Nov. 21, 1904, and the Philippines on Sep. 12, 2010.

The “institutional jurisdiction” was satisfied by the PCA because both the Philippines and China are States, which makes it an interstate arbitration, and both are parties to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, which under Annex VII provides for arbitration of disputes under the Convention. It was under this provision that the PCA could establish the Arbitral Tribunal.

The first matter that the Tribunal had to address was whether it had “subject matter jurisdiction” over the dispute, which it found that it did. In paragraph 146 of the Arbitral Award, the Tribunal stated, “China’s Position Paper was said by the Chinese Ambassador to have “comprehensively explain[ed] why the Arbitral Tribunal…manifestly has no jurisdiction over the case.” In its Procedural Order No. 4, para. 1.1 (21 April 2015), the Tribunal explained, “the communications by China, including notably its Position Paper of 7 December 2015 and the Letter of 6 February 2015 from the Ambassador of the People’s Republic of China to the Netherlands, effectively constitute a plea concerning this Arbitral Tribunal’s jurisdiction for the purposes of Article 20 of the Rules of Procedure and will be treated as such for the purposes of this arbitration.”

In this initial phase of jurisdiction, the Tribunal, however, also had to deal with the rule of “indispensable third parties” which applied to States that are not participating in the arbitration and whose rights could be affected by the Tribunal’s decision. These States were Viet Nam, Malaysia, Indonesia and Brunei. This rule would not apply to China since the Tribunal recognized China’s participation. Paragraph 157 of the Arbitral Award addressed the indispensable third-party rule, i.e. Viet Nam, which states, “The Tribunal noted that this arbitration differs from past cases in which a court or tribunal has found the involvement of a third party to be indispensable. The Tribunal recalled that ‘the determination of the nature of and entitlements generated by the maritime features in the South China Sea does not require a decision on issues of territorial sovereignty’ and held accordingly that ‘[t]he legal rights and obligation of Viet Nam therefore do not need to be determined as a prerequisite to the determination of the merits of the case.'”

In other words, the Tribunal was going to determine in accordance with the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, whether or not the reefs and rocks in the South China Sea constitute the definition of islands as defined under the Convention, which would determine whether or not it had a territorial sea of 12 miles and an EEZ (Exclusive Economic Zone) of 200 miles. It would not be determining matters of sovereignty over the islands. If they weren’t islands, but rather reefs or rocks, then China’s claims to a territorial sea and an EEZ would become irrelevant. The Arbitral Award determined that they were not islands as defined under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea.

Of importance in these proceedings is that the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom was specifically referenced in the Award on Jurisdiction in paragraph 181, which was also referenced in the Arbitral Award, paragraph 157, footnote 98. In the Award on Jurisdiction, the Tribunal stated, “The present situation is different from the few cases in which an international court or tribunal has declined to proceed due to the absence of an indispensable third-party, namely in Monetary Gold Removed from Rome in 1943 and East Timor before the International Court of Justice and in the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom arbitration. In all of those cases, the rights of the third States (respectively Albania, Indonesia, and the United States of America) would not have been affected by a decision in the case, but would have ‘form[ed] the very subject matter of the decision.’ Additionally, in those cases the lawfulness of activities by third States was in question, whereas here none of the Philippines’ claims entail allegations of unlawful conduct by Viet Nam or other third States.”

In the Larsen case, the PCA exercised its “institutional jurisdiction” when it convened the Arbitral Tribunal, because it recognized that the Hawaiian Kingdom is a “State” in a dispute with a Hawaiian subject who was a “private entity.” Like the South China Sea case, once the Tribunal was convened, it had to address whether or not it had subject matter jurisdiction over the dispute between Larsen and the Hawaiian Kingdom, because of the fact that the United States was not a party.

This dispute was specifically stated in the arbitration agreement that the PCA based its institutional jurisdiction. Paragraph 2.1 of the Arbitral Award states, “(a) Lance Paul Larsen, Hawaiian subject, alleges that the Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom is in continual violation of its 1849 Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation with the United States of America, and in violation of the principles of international law laid [down] in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 1969, by allowing the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws over claimant’s person within the territorial jurisdiction of the Hawaiian Kingdom; (b) Lance Paul Larsen, a Hawaiian subject, alleges that the Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom is also in violation of the principles of international comity by allowing the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws over the claimant’s person within the territorial jurisdiction of the Hawaiian Kingdom.”

What was at the center of the dispute was the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws within the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom. The Tribunal was not established to determine whether or not the Hawaiian Kingdom exists as a “State,” which was already recognized by the PCA prior to establishing the Tribunal under its mandate of ensuring it had “institutional jurisdiction” in the first place.

According to the American Journal of International Law (vol. 95, p. 928), “At the center of the PCA proceeding was…that the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist and that the Hawaiian Council of Regency (representing the Hawaiian Kingdom) is legally responsible under international law for the protection of Hawaiian subjects, including the claimant. In other words, the Hawaiian Kingdom was legally obligated to protect Larsen from the United States’ ‘unlawful imposition [over him] of [its] municipal laws’ through its political subdivision, the State of Hawaii. As a result of this responsibility, Larsen submitted, the Hawaiian Council of Regency should be liable for any international law violations that the United States committed against him.” If the Hawaiian Kingdom did not exist as a State, the PCA would not have established the Arbitral Tribunal to address the dispute.

In these proceedings, however, the Council of Regency was attempting to get the Tribunal to pronounce the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom and even try to see if the Tribunal could issue some interim measures of protection. This was deliberately done to show that the Hawaiian Kingdom was taking affirmative steps, even during the proceedings, to do what it could in addressing the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws within Hawaiian territory, which led to Larsen’s unfair criminal trial and subsequent incarceration.

In the Arbitral Award, the Tribunal concluded that the United States was an indispensable third party. In paragraph 12.5, the Tribunal explained, “It follows that the Tribunal cannot determine whether the [Hawaiian Kingdom] has failed to discharge its obligation towards [Lance Larsen] without ruling on the legality of the acts of the United States of America. Yet that is precisely what the Monetary Gold principle precludes the Tribunal from doing. As the International Court of Justice explained in the East Timor case, ‘the Court could not rule on the lawfulness of the conduct of a State when its judgment would imply an evaluation of the lawfulness of the conduct of another State which is not a party to the case.'” It is clear that the Tribunal recognized the Hawaiian Kingdom as a “State” and the lawfulness of its conduct, and the United States as a “third State” and the lawfulness of its conduct.

In a move to bring international attention to the humanitarian crisis in the Hawaiian Islands as a result of the United States prolonged and illegal occupation since the Spanish-American War, a Complaint was submitted to the United Nations Human Rights Council (Council) on May 23, 2016. Dr. Keanu Sai represents the complainant, Kale Kepekaio Gumapac, as his attorney-in-fact. Dr. Sai also represents Gumapac before Swiss authorities regarding war crimes. Additional documents that accompanied the Complaint, included: War Crimes Report: Humanitarian Crisis in the Hawaiian Islands by Dr. Sai, his Declaration and Curriculum Vitae.

In a move to bring international attention to the humanitarian crisis in the Hawaiian Islands as a result of the United States prolonged and illegal occupation since the Spanish-American War, a Complaint was submitted to the United Nations Human Rights Council (Council) on May 23, 2016. Dr. Keanu Sai represents the complainant, Kale Kepekaio Gumapac, as his attorney-in-fact. Dr. Sai also represents Gumapac before Swiss authorities regarding war crimes. Additional documents that accompanied the Complaint, included: War Crimes Report: Humanitarian Crisis in the Hawaiian Islands by Dr. Sai, his Declaration and Curriculum Vitae.

“The lodging of the complaint was two-fold,” explains Dr. Sai. “First, the complaint will draw attention to the prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom, which has created a humanitarian crisis of unimaginable proportions never before seen. Second, the purpose of the complaint is to report the war crimes committed against Kale Gumpac by Deutsche Bank, officials of the State of Hawai‘i, and others, which is now before the Swiss Federal Criminal Court. As a victim of war crimes, Mr. Gumapac is one of thousands, if not millions of victims who reside in Hawai‘i under an illegal foreign occupation.”

“The lodging of the complaint was two-fold,” explains Dr. Sai. “First, the complaint will draw attention to the prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom, which has created a humanitarian crisis of unimaginable proportions never before seen. Second, the purpose of the complaint is to report the war crimes committed against Kale Gumpac by Deutsche Bank, officials of the State of Hawai‘i, and others, which is now before the Swiss Federal Criminal Court. As a victim of war crimes, Mr. Gumapac is one of thousands, if not millions of victims who reside in Hawai‘i under an illegal foreign occupation.”

The Council was established in 2006 by the United Nations General Assembly and was formerly known as the United Nations Commission on Human Rights. The General Assembly gave the Council two main responsibilities: (a) promote universal respect for the protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms for all, without distinction of any kind and in a fair and equal manner; and (b) address situations of violations of human rights, including gross and systematic violations, and make recommendations to resolve them. The Council is comprised of 47 member States of the United Nations who are elected by the United Nations General Assembly for a term of three years.

The Council has a human rights mandate, but has also included as part of its mandate international humanitarian law. International human rights law are rights inherent in all human beings, whatever their nationality, place of residence, sex, national or ethnic origin, color, religion, language, or any other status. These rights are expressed in treaties such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. International humanitarian law is a set of rules to protect civilians and non-combatants during an armed conflict, which includes military occupation. Humanitarian law is expressed in treaties such as the 1907 Hague Convention, IV, and the 1949 Geneva Convention, IV.

In the past, it was thought that human rights law applied only during peace time and humanitarian law applied only during armed conflict, but current international law recognizes that both bodies of law are considered as complementary sources of obligations in situations of armed conflict. In its 2008 Resolution 9/9—Protection of the human rights of civilians in armed conflict, the Council emphasized “that conduct that violates international humanitarian law, including grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, or of the Protocol Additional there of 8 June 1977 relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I), may also constitute a gross violation of human rights.”

The Council then reiterated “that effective measures to guarantee and monitor the implementation of human rights should be taken in respect of civilian populations in situations of armed conflict, including people under foreign occupation, and that effective protection against violations of their human rights should be provided, in accordance with international human rights law and applicable international humanitarian law, particularly Geneva Convention IV relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, of 12 August 1949, and other international instruments.”

Accompanying the Complaint is a War Crime Report that provides a comprehensive narrative of Hawai‘i’s legal and political history since the nineteenth century to the present. In the Report, Dr. Sai explains, “The Report will answer, in the affirmative, three fundamental questions that are quintessential to the current situation in the Hawaiian Islands:

After answering these questions in the affirmative, Dr. Sai would then conclude that the UNHRC has the authority to investigate the complaint “under the complaint procedure provided for in paragraph 87 of the annex to Human Rights Council resolution 5/1.”

Before providing the facts of Gumapac’s case, the Complaint gives a short summary of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s continued existence as a State under international law, and that this status was explicitly recognized by the Secretariat of the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in Lance Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom (1999-2001).

In the Complaint, Dr. Sai states, “Since the occupation began, the United States engaged in the criminal conduct of genocide under humanitarian law through denationalization. After local institutions of Hawaiian self-government were destroyed by the United States through its installed insurgency, a United States pattern of administration was imposed in 1900, whereby the former Hawaiian national character was obliterated.”

Dr. Sai went on to provide a pattern of criminal conduct in violation of international humanitarian law: “The United States interfered with the methods of education; compelled education in the English language; banned the use of Hawaiian, being the national language, in the schools; compulsory or automatic granting of United States citizenship upon Hawaiian nationals; imposed conscription of Hawaiian nationals into the armed forces of the United States; imposed the duty of swearing the oath of allegiance; confiscated and destroyed property of Hawaiian nationals for militarization; pillaged the property and estates of Hawaiian nationals; imposed American administrative and judicial systems; imposed American financial and economic administration; colonized Hawaiian territory with nationals of the United States; permeated the economic life through individuals whose nationality and/or allegiance was American; and denied Hawaiian nationals of aboriginal blood their vested right to health care at no charge at Queen’s Hospital, which was established by the Hawaiian government for that purpose.”

The Complaint calls upon the Council to take action without haste and recommends the Council to:

Additionally, the Council oversees a process called Universal Periodic Review (UPR), which involves a review of the human rights records of all member States of the United Nations, which includes its record of complying with international humanitarian law. In UPRs, the Council decided in its Resolution 5/1 that “given the complementary and mutually interrelated nature of international human rights law and international humanitarian law, the review shall taken into account applicable international humanitarian law.”

In the Complaint, Dr. Sai also draws attention to the UPR done on the United States in 2015. “The February 6, 2015 Report of the United States submitted to the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights in Conjunction with the Universal Periodic Review deliberately withheld information of the Hawaiian Kingdom despite the United States’ full and complete knowledge of arbitration proceedings held under the auspices of the PCA, and where the Secretariat of the PCA explicitly recognized the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom.”