When the United Nations was established in 1945 one of its goals was to address the colonial possessions of the allied countries who prevailed during World War II. Article 73(e) of the UN Charter required these countries to transmit information regarding their territorial possessions and the progress of these territories towards a full measure of self-government. The term “self” means for oneself and not imposed, and “government” means a system of governing or administration. These colonial possessions did not have a government of their own and came to be known as non-self-governing territories.

The process of achieving “self-government” is called “self-determination.” According to the United Nations Repertoire of the Practice of the Security Council, “Article 1(2) establishes that one of the main purposes of the United Nations, and thus the Security Council, is to develop friendly international relations based on respect for the ‘principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples.’ The case studies in this section cover instances where the Security Council has discussed situations with a bearing on the principle of self-determination and the right of peoples to decide their own government, which may relate to the questions of independence, autonomy, referenda, elections, and the legitimacy of governments.”

According to UN General Assembly Resolution 1541 (XV), a non-self-governing territory “can be said to have reached a full measure of self-government by: (a) Emergence as a sovereign independent State; (b) Free association with an independent State; or (c) Integration with an independent State.” In other words, a non-self-governing territory was never a sovereign independent State, never in association with an independent State, or was never integrated with an independent State.

According to Dr. James Summers, Peoples and International Law (p. 210), “No conditions were set for self-government by independence, but conditions were attached to integration and free association. Free association…was to be established by the free and voluntary choice of the people concerned expressed by informed and democratic means. The individuality and culture of the territory had to be respected and its people had the right to determine their internal constitution without interference. This status, moreover, was not necessarily permanent and could later be changed by democratic means. Integration…was to take place on the basis of equality: people were to have equal status, citizenship, fundamental rights, representations and participation.”

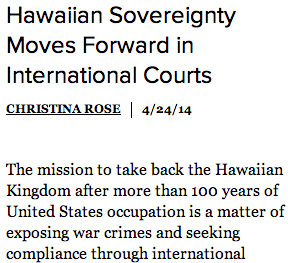

In 1946, prior to the passage of the Hawai‘i Statehood Act by the United States Congress, the United States misrepresented its relationship with Hawai’i when its permanent representative to the United Nations identified Hawai’i as a non-self-governing territory under the administration of the United States since 1898. In accordance with Article 73(e) of the U.N. Charter, the United States permanent representative erroneously reported Hawai’i as a non-self-governing territory, which implied Hawai‘i was never a “sovereign independent State.”

On June 4, 1952, United Nations Secretary General Trygve Halvdan Lie reported information submitted to him by United States Ambassador to the United Nations, Warren Austin, regarding American Samoa, Hawai‘i, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. In this report, the United States Ambassador made no mention that Hawai‘i was an independent State since 1843 and that its government was illegally overthrown by U.S. forces, which was later settled by an executive agreement through mediation and exchange of notes. The representative also failed to disclose diplomatic protests that succeeded in preventing the second attempt to annex the Islands by a treaty of cession in 1897. Instead, the representative provided a picture of Hawai‘i as if it were a non-self-governing territory. The report stated,

On June 4, 1952, United Nations Secretary General Trygve Halvdan Lie reported information submitted to him by United States Ambassador to the United Nations, Warren Austin, regarding American Samoa, Hawai‘i, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. In this report, the United States Ambassador made no mention that Hawai‘i was an independent State since 1843 and that its government was illegally overthrown by U.S. forces, which was later settled by an executive agreement through mediation and exchange of notes. The representative also failed to disclose diplomatic protests that succeeded in preventing the second attempt to annex the Islands by a treaty of cession in 1897. Instead, the representative provided a picture of Hawai‘i as if it were a non-self-governing territory. The report stated,

“The Hawaiian Islands were discovered by James Cook in 1778. At that time divided into several petty chieftainships, they were soon afterwards united into one kingdom. The Islands became an important port and recruiting point for the early fur and sandalwood traders in the North Pacific, and the principal field base for the extensive whaling trade. When whaling declined after 1860, sugar became the foundation of the economy, and was stimulated by a reciprocity treaty with the United States (1896).

“The Hawaiian Islands were discovered by James Cook in 1778. At that time divided into several petty chieftainships, they were soon afterwards united into one kingdom. The Islands became an important port and recruiting point for the early fur and sandalwood traders in the North Pacific, and the principal field base for the extensive whaling trade. When whaling declined after 1860, sugar became the foundation of the economy, and was stimulated by a reciprocity treaty with the United States (1896).

American missionaries went to Hawaii in 1820; they reduced the Hawaiian language to written form, established a school system, and gained great influence among the ruling chiefs. In contact with foreigners and western culture, the aboriginal population steadily declined. To replace this loss and to furnish labourers for the expanding sugar plantations, large-scale immigration was established.

When later Hawaiian monarchs showed a tendency to revert to absolutism, political discords and economic stresses produced a revolutionary movement headed by men of foreign birth and ancestry. The Native monarch was overthrown in 1893, and a republic government established. Annexation to the United States was one aim of the revolutionists. After a delay of five years, annexation was accomplished.

…The Hawaiian Islands, by virtue of the Joint Resolution of Annexation and the Hawaiian Organic Act, became an integral part of the United States and were given a territorial form of government which, in the United States political system, precedes statehood.”

In 1959, the Secretary General received a communication from the United States permanent representative that they will no longer transmit information regarding Hawai‘i because it was supposedly “integrated” into the United States under a new constitution that would take effect on August 21, 1959. This resulted in a General Assembly resolution stating it “Considers it appropriate that the transmission of information in respect of Alaska and Hawaii under Article 73e of the Charter should cease.”Evidence that the United Nations was not aware of Hawaiian independence since 1843 can be shown from the following statement by the United Nations’ Repertory of Practice of United Nations Organs, Extracts relating to Article 73 of the Charter of the United Nations, Supplement No. 1 (1955-1959), volume 3, at200, para. 101.

In 1959, the Secretary General received a communication from the United States permanent representative that they will no longer transmit information regarding Hawai‘i because it was supposedly “integrated” into the United States under a new constitution that would take effect on August 21, 1959. This resulted in a General Assembly resolution stating it “Considers it appropriate that the transmission of information in respect of Alaska and Hawaii under Article 73e of the Charter should cease.”Evidence that the United Nations was not aware of Hawaiian independence since 1843 can be shown from the following statement by the United Nations’ Repertory of Practice of United Nations Organs, Extracts relating to Article 73 of the Charter of the United Nations, Supplement No. 1 (1955-1959), volume 3, at200, para. 101.

“Though the General Assembly considered that the manner in which Territories could become fully self-governing was primarily through the attainment of independence, it was observed in the Fourth Committee that the General Assembly had recognized in resolution 748 (VIII) that self-government could also be achieved by association with another State or group of States if the association was freely chosen and was on a basis of absolute equality. There was unanimous agreement that Alaska and Hawaii had attained a full measure of self-government and equal to that enjoyed by all other self-governing constituent states of the United States. Moreover, the people of Alaska and Hawaii had fully exercised their right to choose their own form of government.”

Although the United Nations passed two resolutions acknowledging Hawai‘i to be a non-self-governing territory that has been under the administration of the United States of America since 1898 and was granted “so-called” a full measure of self-governance in 1959, it did not affect the continuity of the Hawaiian State because, foremost, United Nations resolutions are not binding on member States of the United Nations, let alone a non-member State—the Hawaiian Kingdom. Professor Crawford explains, The Creation of States in International Law (p. 113), “Of course, the General Assembly is not a legislature. Mostly its resolutions are only recommendations, and it has no capacity to impose new legal obligations on States.” Secondly, the information provided to the General Assembly by the United States was distorted and flawed. In East Timor, Portugal argued that resolutions of both the General Assembly and the Security Council acknowledged the status of East Timor as a non-self-governing territory and Portugal as the administering power and should be treated as “givens.” The International Court of Justice, however, did not agree and in its judgment (p. 103) found “that it cannot be inferred from the sole fact that the above-mentioned resolutions of the General Assembly and the Security Council refer to Portugal as the administrating Power of East Timor that they intended to establish an obligation on third States.”

Even more problematic is when the decisions embodied in the resolutions as “givens” are wrong. Acknowledging this possibility, Professor Bowett, The Impact of Security Council Decisions on Dispute Settlement Procedures (p. 97), states, “where a decision affects a State’s legal rights or responsibilities, and can be shown to be unsupported by the facts, or based upon a quite erroneous view of the facts, or a clear error of law, the decision ought in principle to be set aside.” Marco Öberg, The Legal Effects of Resolutions of the UN Security Council and General Assembly in the Jurisprudence of the ICJ (p. 892), also agrees and acknowledges that resolutions “may have been made on the basis of partial information, where not all interested parties were heard, and/or too urgently for the facts to be objectively established.” As an example, Öberg cited Security Council Resolution 1530, March 11, 2004, that “misidentified the perpetrator of the bomb attacks carried out in Madrid, Spain, on the same day.”

There exists a common misunderstanding that stems from Americanization, which promoted the lie that Hawai‘i was a colony of the United States, that Hawai‘i did not fully exercise “self-determination” in 1959 because there was no option for the people to choose to become a “sovereign independent State.” This has resulted in a paradoxical fringe movement of “re-inscription” onto to the Article 73(e) list of non-self-governing territories. The inherent contradiction of this argument is that in order to “re-inscribe” is to start from the premise that Hawai‘i was never a “sovereign independent State” in order to choose through a process of self-determination for Hawai‘i to be an “independent sovereign State.”

The underlying paradox to this argument is that to re-inscribe is to place the United States in a position of power as the administrator over a territory that is not a sovereign independent State, in order to negotiate with the United States to become a sovereign independent State. This is a contradiction, especially after the Permanent Court of Arbitration stated in its 2001 Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom Arbitral Award that Hawai‘i “existed as an independent State recognized as such by the United States of America, the United Kingdom and various other States, including by exchanges of diplomatic or consular representatives and the conclusion of treaties.”

There is no evidence in the history of international law where an already established sovereign independent State was ever considered a non-self-governing territory, because international law provides for the rule preserving the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a sovereign independent State even during an illegal and prolonged occupation.