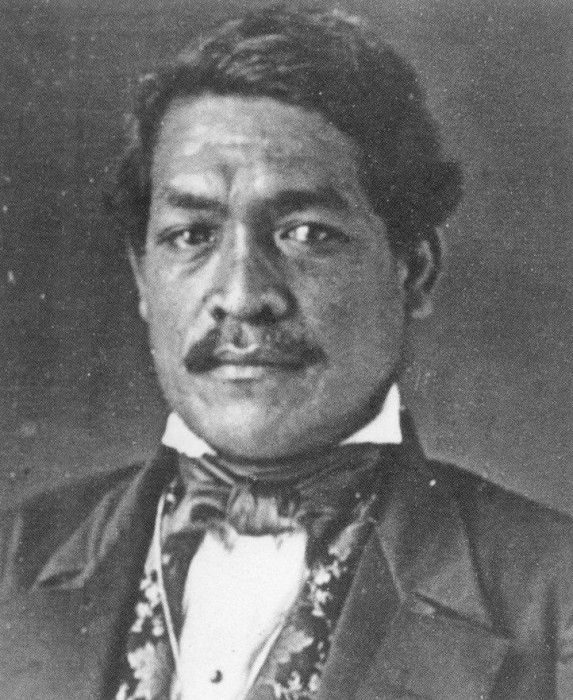

On June 7, 1839, Kamehameha III proclaimed an expanded uniform code of laws preceded by a “Declaration of Rights” that formally acknowledged and vowed to protect the natural rights of life, limb, and liberty for both chiefs and people. The code provided that “no chief has any authority over any man, any farther than it is given him by specific enactment, and no tax can be levied, other than that which is specified in the printed law, and no chief can act as a judge in a case where he is personally interested, and no man can be dispossessed of land which he has put under cultivation except for crimes specified in the law.”

On June 7, 1839, Kamehameha III proclaimed an expanded uniform code of laws preceded by a “Declaration of Rights” that formally acknowledged and vowed to protect the natural rights of life, limb, and liberty for both chiefs and people. The code provided that “no chief has any authority over any man, any farther than it is given him by specific enactment, and no tax can be levied, other than that which is specified in the printed law, and no chief can act as a judge in a case where he is personally interested, and no man can be dispossessed of land which he has put under cultivation except for crimes specified in the law.”

1840 Constitution

On October 8, 1840, Kamehameha III approved the first constitution incorporating the Declaration of Rights as its preamble.

The purpose of a written constitution was “to lay down the general features of a system of government and to define to a greater or less extent the powers of such government, in relation to the rights of persons on the one hand, and on the other…in relation to certain other political entities which are incorporated in the system.” The first constitution did not provide for separation of powers (e.g. executive, legislative and judicial). The King’s duty was to execute the laws of the land, serve as chief judge of the Supreme Court, and sit as a member of the House of Nobles that would enact laws together with representatives chosen from the people. The first constitution was not a limitation of power, but a sharing of power. Kamehameha III declared and established the equality of all his subjects before the law and voluntarily divested himself of his power as an absolute Ruler. According to the Hawaiian Supreme Court, in Rex v. Booth, 3 Hawai‘i 616, 630 (1863):

“King Kamehameha III originally possessed, in his own person, all the attributes of absolute sovereignty. Of his own free will he granted the Constitution of 1840, as a boon to his country and people, establishing his Government upon a declared plan or system, having reference not only to the permanency of his Throne and Dynasty, but to the Government of his country according to fixed laws and civilized usage, in lieu of what may be styled the feudal, but chaotic and uncertain system, which previously prevailed.”

In 1845, Kamehameha III refocused his attention on domestic affairs, and the organization and maintenance of the newly established constitutional monarchy. On October 29th, he commissioned Robert Wyllie of Scotland to be Minister of Foreign Affairs; G.P. Judd, a former missionary, as Minister of Finance; William Richards as Minister of Education; and John Ricord, as Attorney General. All were granted Hawaiian citizenship prior to their appointments. These appointments sparked controversy and renewed concerns of foreign takeover. Responding to a slew of appeals to remove these foreign advisors for native chiefs, Kamehameha III wrote the following letter that speaks to the tenor of the time and circumstances the kingdom faced:

“Kind greetings to you with kindly greetings to the old men and women of my ancestors’ time. I desire all the good things of the past to remain such as the good old law of Kamehameha that “the old women and the old men shall sleep in safety by the wayside,” and to unite with them what is good under these new conditions in which we live. That is why I have appointed foreign officials, not out of contempt for the ancient wisdom of the land, but because my native helpers do not yet understand the laws of the great countries who are working with us. That is why I have dismissed them. I see that I must have new officials to help with the new system under which I am working for the good of the country and of the old men and women of the country. I earnestly desire to give places to the commoners and to the chiefs, as they are able to do the work connected with the office. The people who have learned the new ways I have retained. Here is the name of one of them, G.L. Kapeau, Secretary of the Treasury. He understands the work very well, and I wish there were more such men. Among the chiefs Leleiohoku, Paki, and John Young [Keoniana] are capable of filling such places and they already have government offices, one of them over foreign officials. And as soon as the young chiefs are sufficiently trained I hope to give them the places. But they are not now able to become speakers in foreign tongues. I have therefore refused the letters of appeal to dismiss the foreign advisors, for those who speak only the Hawaiian tongue.”

John Ricord arrived in the Hawaiian Islands from Oregon on February 27, 1844 and was later appointed Attorney General on March 9th. He was an attorney by trade and well versed in both the civil law of continental Europe and the common law of both Britain and the United States. The kingdom was only in its fourth year of constitutional governance and the shortcomings of the first constitution began to show. One of Ricord’s first tasks was to establish a diplomatic code for Kamehameha III and the Royal Court, which was based on the principles of the 1815 Vienna Conference. His second and more important task was to draft a code to re-organize the executive and judicial departments for submission to the Legislature for approval.

In a report to the Legislature, Ricord concluded that, “there is an almost total deficiency of laws, suited to the Hawaiian Islands as a recognized nation in reciprocity with others so mighty, so enlightened and so well organized as Great Britain, France, the United States of America, and Belgium.” Ricord observed that, “the Constitution had not been carried into full effect [and] its provisions needed assorting and arranging into appropriate families, and prescribed machinery to render them effective.”

The underlying issue was which system of law should serve as a model: France and Belgium’s governments based on a Civil or Roman law tradition; or Great Britain and the United States’ tradition of Common law. Ricord explained:

“The laws of Rome, that government from which all other governments of Europe, Western Asia and Africa descended, could not be used for Hawai‘i, nor could those of England, France or any other country. The Hawaiian people must have laws adapted to their mode of living. But it is right to study the laws of other peoples, and fitting that those who conduct law offices in Hawai‘i should understand these other laws and compare them to see which are adapted to our way of living and which are not.”

Complying with a legislative resolution, Ricord’s draft code was based on a hybrid of both civil and common law. Because the Hawaiian Islands were at the international crossroads of trade and commerce across the Pacific Ocean, merchants from many countries had influenced the evolution of Hawaiian law. Governmental organization leaned toward the principles of English and American common law, infused with some civil law, but at the very core was distinctively Hawaiian.

1852 Constitution

In 1851, the Legislature passed a resolution calling for the appointment of three commissioners to propose amendments to the first Constitution of 1840. One was to be chosen by the King, one by the Nobles, and one by the Representatives. Elected Representative William Little Lee headed the commission and followed the structure and organization of the 1780 Massachusetts Constitution, the most advanced of any constitution at that time. It was organized into four parts: a preamble; a declaration of rights; a framework of government describing the legislative, executive and judicial branches; and an amendment article. The revised Hawaiian Constitution was submitted to the Legislature and approved by both the House of Nobles and the House of Representatives, and signed into law by the King on June 14, 1852, which became known as the 1852 Constitution.

The amended constitution was similar in structure to the Massachusetts Constitution, but with a different order: a declaration of rights; a framework of government that described the functions of the executive subdivided into five sections, the legislative and judicial powers; and an article describing the mode of amending the constitution.

The theory of a constitutional monarchy states the “three powers of a modern [constitutional monarchy] have distinct functions, but are not completely separate. As part of an interdependent whole, each power is defined not only by its own particular function, but also by the other powers which limit and interact with it.” The revised constitution retained remnants of centralized rule, giving the Crown the authority to alter the constitution or even cede the kingdom to a foreign state without legislative approval. These provisions would allow the King to act swiftly if circumstances demanded. In particular, these provisions of the 1852 constitution included:

“Article 39. The King, by and with the approval of His Cabinet and Privy Council, in case of invasion or rebellion, can, place the whole Kingdom, or any part of it under martial law; and he can ever alienate it, if indispensable to free it from the insult and oppression of any foreign power.

Article 45. All important business for the Kingdom which the King chooses to transact in person, he may do, but not without the approbation of the Kuhina Nui. The King and Kuhina Nui shall have a negative on each other’s public acts.”

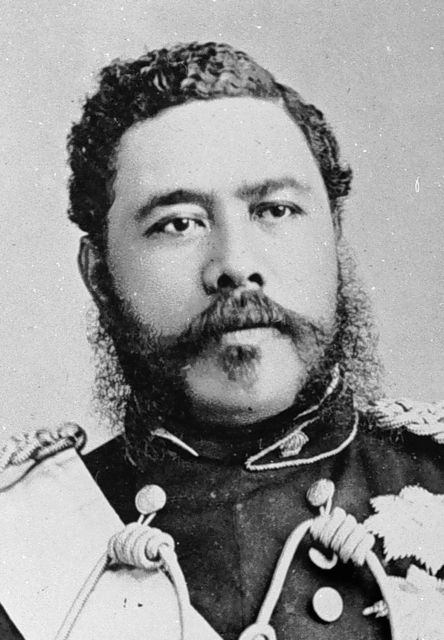

On December 15, 1854, Kamehameha III died and was succeeded by his adopted son and heir apparent, Alexander Liholiho, who would after be called Kamehameha IV. On November 30th 1863, Kamehameha IV died unexpectedly, and left the Kingdom without a successor. On the same day, the Premier, Victoria Kamamalu, in Privy Council, proclaimed Lot Kapuaiwa to be the successor to the throne in accordance with Article 25 of the Constitution of 1852, and the Nobles confirmed him. Lot Kapuaiwa was thereafter called Kamehameha V. Article 47, of the Constitution of 1852, provided that “whenever the throne shall become vacant by reason of the King’s death the Kuhina Nui shall perform all the duties incumbent on the King, and shall have and exercise all the powers, which by this Constitution are vested in the King.”

Victoria Kamamalu provided continuity for the office of the Crown pending the appointment and confirmation of Lot Kapuaiwa. Upon his ascension, Kamehameha V refused to take the oath of office until the 1852 Constitution was altered in order to remove those sovereign prerogatives that ran contrary to the principles of a constitutional monarchy, namely articles 45 and 94.

Victoria Kamamalu provided continuity for the office of the Crown pending the appointment and confirmation of Lot Kapuaiwa. Upon his ascension, Kamehameha V refused to take the oath of office until the 1852 Constitution was altered in order to remove those sovereign prerogatives that ran contrary to the principles of a constitutional monarchy, namely articles 45 and 94.

Kamehameha V knew that he had a choice not to take the oath, and that his refusal to take the oath was constitutionally authorized by article 94 of  the Constitution, which provided that the “King, after approving this Constitution, shall take the following oath.” Since he did not approve the Constitution, he was not required to take the oath. Kamehameha V felt the constitutional provisions should be changed since they were a source of great difficulty for his late brother Kamehameha IV, and would continue to be problematic for him and the Legislative Assembly. If he did take the oath, he would have bound himself to the constitution whereby any change or amendment to the constitution was vested solely with the Legislative Assembly. By not taking the oath, he reserved for himself the responsibility of change, which ironically was authorized by the very constitution he sought to amend.

the Constitution, which provided that the “King, after approving this Constitution, shall take the following oath.” Since he did not approve the Constitution, he was not required to take the oath. Kamehameha V felt the constitutional provisions should be changed since they were a source of great difficulty for his late brother Kamehameha IV, and would continue to be problematic for him and the Legislative Assembly. If he did take the oath, he would have bound himself to the constitution whereby any change or amendment to the constitution was vested solely with the Legislative Assembly. By not taking the oath, he reserved for himself the responsibility of change, which ironically was authorized by the very constitution he sought to amend.

1864 Constitution

Kamehameha V and his predecessor recognized articles 45 and 94 as a hindrance to responsible government, and therefore he convened the first Constitutional Convention to draft a new constitution on July 7, 1864. Between July 7 and August 8, 1864, each article in the proposed constitution was read and discussed until the Convention arrived at article 62. The King and Nobles wanted to insert property qualifications for representatives and voters, but the elected delegates refused. After days of debate over article 62, the Convention was deadlocked. As a result, Kamehameha V, in an act of irony, dissolved the convention and exercised his sovereign prerogative under article 45, and he annulled the 1852 constitution and proclaimed a new constitution on August 20, 1864. In other words, Kamehameha V utilized the very provision of absolutism in the 1852 Constitution (Article 45) he sought to remove by a Constitutional Convention, in order to promulgate the 1864 Constitution that the Constitutional Convention could not remove.

In his speech at the opening of the Legislative Assembly of 1864, Kamehameha V explained his action by making specific reference to the “forty-fifth article [that] reserved to the Sovereign the right to conduct personally, in cooperation with the Kuhina Nui (Premier), but without the intervention of a Ministry or the approval of the Legislature, such portions of the public business as he might choose to undertake.” The constitution was not new, but rather the same draft that was before the convention with the exception of the property qualifications for Representatives and voters as embodied in Articles 61 and 62.

Article 61: No person shall be eligible for a Representative of the People, who is insane or an idiot; nor unless he be a male subject of the Kingdom, who shall have arrived at the full age of Twenty-One years—who shall know how to read and write—who shall understand accounts—and shall have been domiciled in the Kingdom for at least three years, the last of which shall be the year immediately preceding his election; and who shall own Real Estate, within the Kingdom, of a clear value, over and above all incumbrances, of at least Five Hundred Dollars; or who shall have an annual income of at least Two Hundred and Fifty Dollars; derived from any property, or some lawful employment.

Article 62: “Every male subject of the Kingdom, who shall have paid his taxes, who shall have attained the age of twenty years, and shall have been domiciled in the Kingdom for one year immediately preceding the election; and shall be possessed of Real Property in this Kingdom, to the value over and above all incumbrances of One Hundred and Fifty Dollars or a Lease-hold property on which the rent is Twenty-five Dollars per year—or of an income of not less than Seventy-five Dollars per year, derived from any property or some lawful employment, and shall know how to read and write, if born since the year 1840, and shall have caused his name to be entered on the list of voters of his District as may be provided by law, shall be entitled to one vote for the Representative or Representatives of that District. Provided, however, that no insane or idiotic person, nor any person who shall have been convicted of any infamous crime within this Kingdom, unless he shall have been pardoned by the King, and by the terms of such pardon have been restored to all the rights of a subject, shall be allowed to vote.”

The office of Premier was also eliminated under the new constitution, which also provided that no act of the Crown was valid unless countersigned by a responsible Minister from the Cabinet, who answered to the Legislative Assembly and could be removed by a vote of a lack of confidence or impeachment proceedings.

The function of the Privy Council was greatly reduced, and a Regency replaced the function of Premier if the King died, leaving a minor heir, who would “administer the Government in the name of the King, and exercise all the powers which are Constitutionally vested in the King.” The Crown was bound to take the oath of office upon ascension to the throne, and the Legislative Assembly had the sole authority to amend or alter the constitution. The Legislative Assembly was now a unicameral body comprised of appointed Nobles and Representatives elected by the people. The constitution also provided that the “Supreme Power of the Kingdom in its exercise, is divided into the Executive, Legislative, and Judicial; these shall always be preserved distinct.” Thus, the separation of powers doctrine was fully enshrined in Hawaiian constitutional governance.

The 1864 Legislative Assembly appointed a special committee comprised of Godfrey Rhodes, John I‘i, and J.W.H. Kauwahi to respond to Kamehameha V’s opening speech of the new legislature. The committee recognized the constitutionality of the King’s prerogative under the former constitution and acknowledged that this “prerogative converted into a right by the terms of the [1852] Constitution, Your Majesty has now parted with, both for Yourself and Successors, and this Assembly thoroughly recognizes the sound judgment by which Your Majesty was actuated in the abandonment of a privilege, which, at some future time might have been productive of untold evil to the nation.”

The Crown was not only authorized by law to do what had been done, but the action of Kamehameha V further limited his own authority under the former constitution. He was the last Monarch to exercise absolutism. No other Monarch could unilaterally change or amend the constitution as Kamehameha V did because the provision of Article 45 was no longer in the 1864 Constitution, and the only way to change or amend the constitution was according to Article 80 which vests that right in the Legislative Assembly together with the Monarch.

In compliance with Article 80, a resolution to amend the constitution was introduced into the Legislative Assembly in the year 1873 when the legislature was called into special session to elect King Lunalilo. When the Legislative Assembly was re-called into special session the following year in 1874 to elect King Kalakaua, the Legislative Assembly also repealed the property qualifications embodied in articles 61 and 62 of the 1864 constitution, but maintained the literacy qualification.

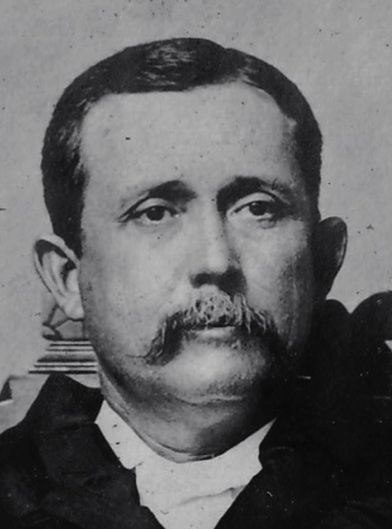

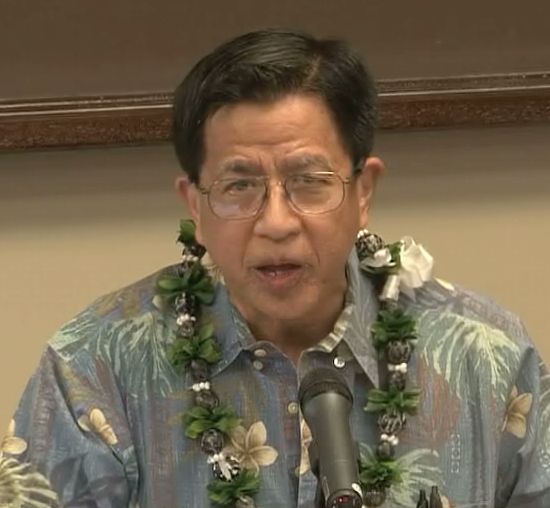

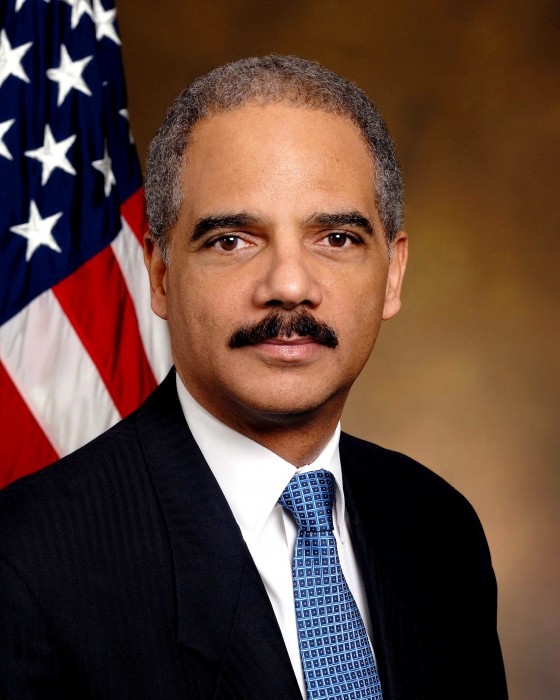

HONOLULU (September 19, 2014) – Senior law professor Williamson B.C. Chang has reported to U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder, Jr. that war crimes have and continue to be committed in the Hawaiian Islands. Professor Chang is a faculty member of the University of Hawai‘i William S. Richardson School of Law and has been with the law school for the past thirty-eight years.

HONOLULU (September 19, 2014) – Senior law professor Williamson B.C. Chang has reported to U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder, Jr. that war crimes have and continue to be committed in the Hawaiian Islands. Professor Chang is a faculty member of the University of Hawai‘i William S. Richardson School of Law and has been with the law school for the past thirty-eight years. In the letter addressed to Attorney General Holder, Professor Chang described his reporting of war crimes as being obligated under Federal criminal law and if he did not report the war crimes he could be fined or imprisoned for three years. “Pursuant to 18 U.S.C. §4—Misprision of felony, I am legally obligated to report to you the knowledge I have about multiple felonies that prima facie have been and continue to be committed here in the Hawaiian Islands,” Chang said. “I have been made aware of these felonies through the memorandum by political scientist David Keanu Sai, Ph.D., who was contracted by the State of Hawai‘i Office of Hawaiian Affairs, entitled Memorandum for Ka Pouhana, CEO of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs regarding Hawai‘i as an Independent State and the Impacts it has on the Office of Hawaiian Affairs.”

In the letter addressed to Attorney General Holder, Professor Chang described his reporting of war crimes as being obligated under Federal criminal law and if he did not report the war crimes he could be fined or imprisoned for three years. “Pursuant to 18 U.S.C. §4—Misprision of felony, I am legally obligated to report to you the knowledge I have about multiple felonies that prima facie have been and continue to be committed here in the Hawaiian Islands,” Chang said. “I have been made aware of these felonies through the memorandum by political scientist David Keanu Sai, Ph.D., who was contracted by the State of Hawai‘i Office of Hawaiian Affairs, entitled Memorandum for Ka Pouhana, CEO of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs regarding Hawai‘i as an Independent State and the Impacts it has on the Office of Hawaiian Affairs.”