It has been a common misunderstanding by individuals who are not familiar with international law that the laws of occupation did not become a part of international law until the year 1899, which is when the Hague Conventions were signed. The 1907 Hague Conventions later superseded these Conventions. Because of the chronology, as the argument goes, the United States was not bound by the Hague Conventions because the occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom occurred one year before in 1898. And since laws do not have a retroactive effect—unless explicitly stated, the United States was not bound to follow a law that wasn’t in effect at the time the occupation occurred. This would be inaccurate.

First, there are two primary sources of international law—customary and treaties. Customary international law is defined by the International Court of Justice as “evidence of a general practice accepted as law.” Since there is no law making body at the international level, such as legislative bodies within countries, international law is created by the consent and actions of independent and sovereign States, since international law is literally law “between” nations (States). As a result, States themselves create international law through practice and if all States are doing the same “general practice” it is considered customary international law that all States are bound by. An example of customary international law is diplomatic immunity. Customary international law can also be codified into a treaty, which is the other primary source of international law.

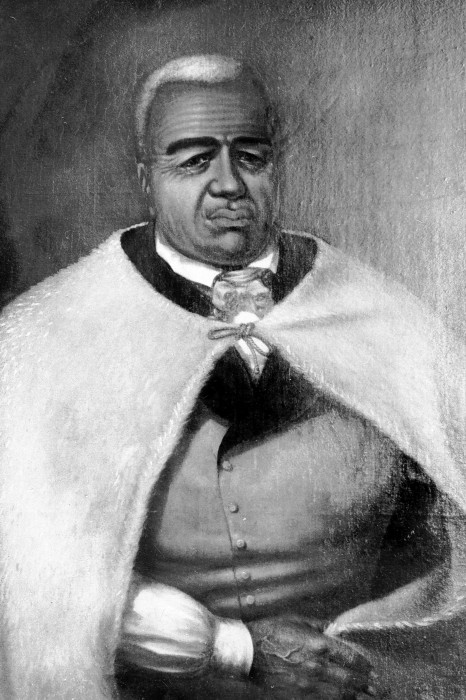

When States met in the city The Hague in the Netherlands in 1899 to codify the laws of war and occupation, they did not create new law but merely codified what was already regarded as customary international law. According to Professor Graber, The Development of the Law of Belligerent Occupation: 1863-1914 (1949), “nothing distinguishes the writing of the period following the 1899 Hague code from the writing prior to that code (p. 143).” With regard to the occupation of a State’s territory during war, the laws of the occupied State must be administered by the occupant State since occupation does not transfer sovereignty to the occupier.

This requirement was codified under Article 43 of the 1899 Hague Convention, II, which states, “The authority of the legitimate power having actually passed into the hands of the occupant, the latter shall take all steps in his power to re-establish and insure, as far as possible, public order and safety, while respecting, unless absolutely prevented, the laws in force in the country.” Although the United States signed and ratified both Hague Regulations, which post-date the occupation of the Hawaiian Islands, the “text of Article 43,” according to Professor Benvenisti, The International Law of Occupation (1993), “was accepted by scholars as mere reiteration of the older law, and subsequently the article was generally recognized as expressing customary international law (p. 8).”

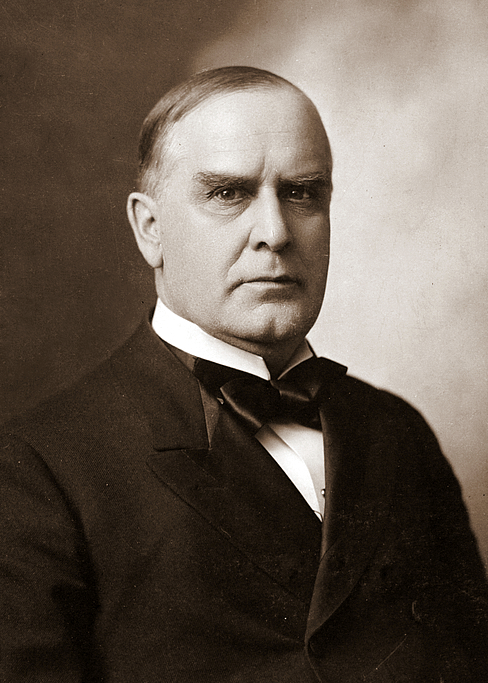

When the Spanish-American War broke out, President McKinley proclaimed that the Spanish-American war would “be conducted upon principles in harmony with the present views of nations and sanctioned by their recent practice,” and acknowledged the constraints and protection international laws provide to all sovereign states, whether belligerent or neutral.

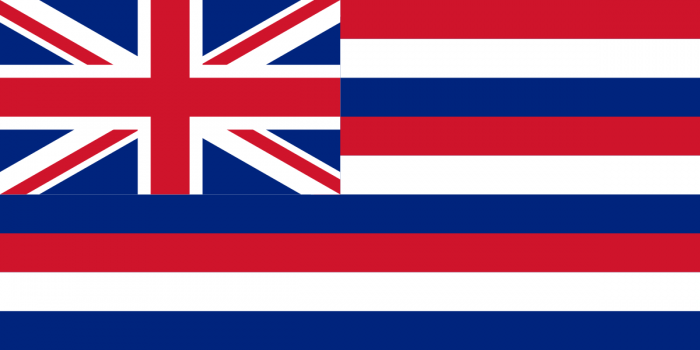

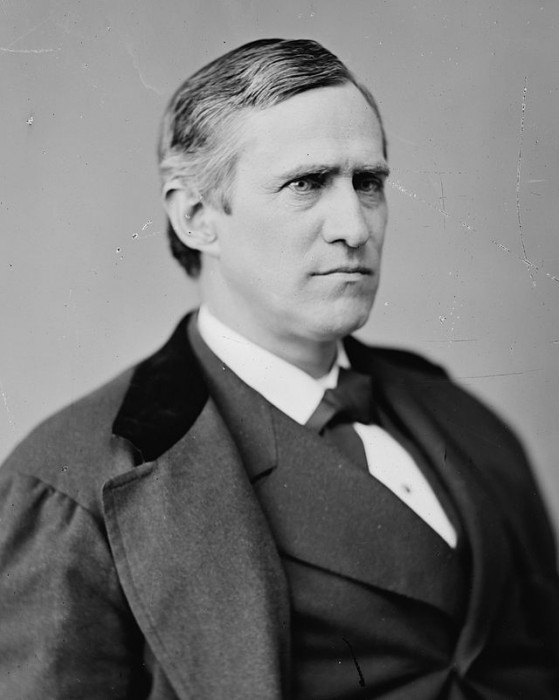

When the Spanish-American War broke out, President McKinley proclaimed that the Spanish-American war would “be conducted upon principles in harmony with the present views of nations and sanctioned by their recent practice,” and acknowledged the constraints and protection international laws provide to all sovereign states, whether belligerent or neutral. As noted by Senator Henry Cabot Lodge during the Senate’s secret session, Hawai`i, as a sovereign and neutral state, was no exception when it was occupied by the United States during its war with Spain. Article 43 of the 1899 Hague Convention, II, which remained the same under the 1907 amended Hague Convention, IV, delimits the power of the occupant and serves as a fundamental bar on its free agency within an occupied State, whether belligerent or neutral.

As noted by Senator Henry Cabot Lodge during the Senate’s secret session, Hawai`i, as a sovereign and neutral state, was no exception when it was occupied by the United States during its war with Spain. Article 43 of the 1899 Hague Convention, II, which remained the same under the 1907 amended Hague Convention, IV, delimits the power of the occupant and serves as a fundamental bar on its free agency within an occupied State, whether belligerent or neutral.

On April 25, 1898, the U.S. Congress declared war against Spain and battles were fought in the Spanish colonies of the Philippines and Guam in the Pacific, and the Spanish colonies of Cuba and Puerto Rico in the Caribbean. Although fighting ceased in Puerto Rico and Cuba on July 25 under an armistice agreement signed in Washington, D.C., fighting continued in the Philippines until August 13 when a second armistice was signed. Both armistices suspended hostilities pending the negotiation of a treaty of peace that was eventually signed in Paris on December 10, 1898.

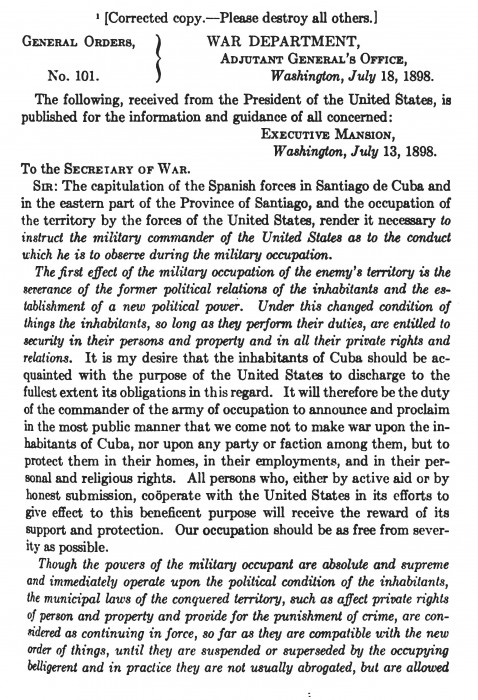

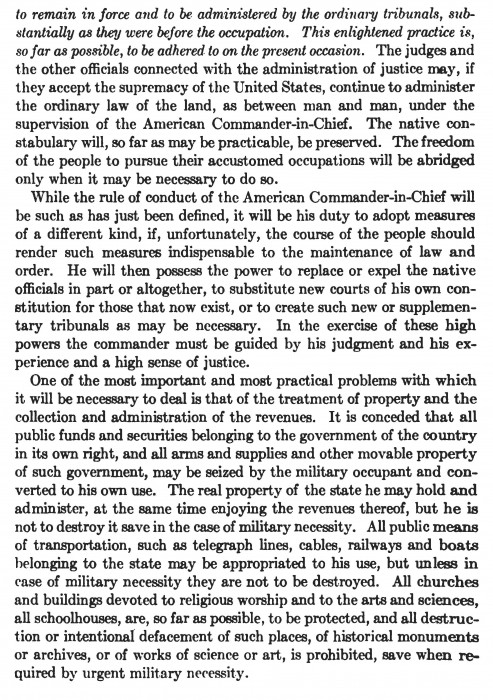

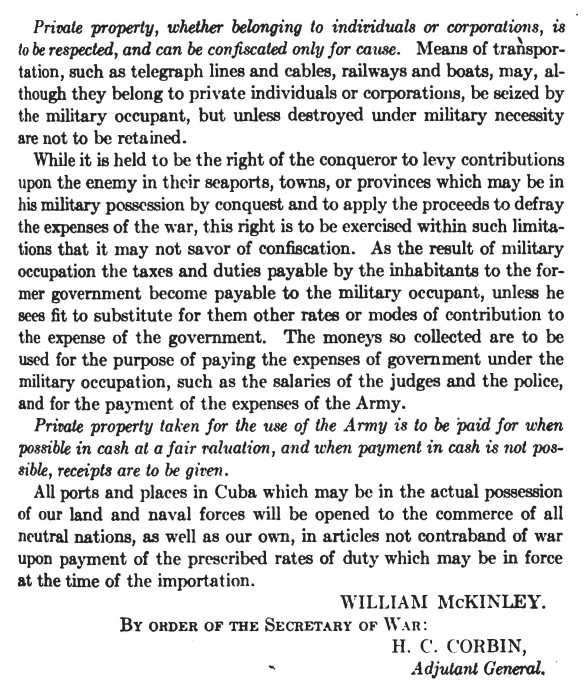

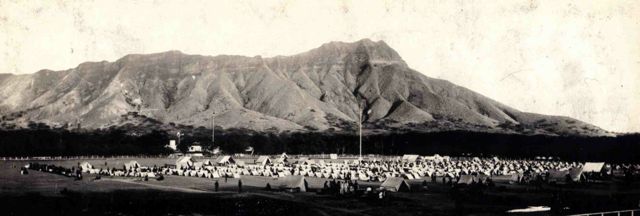

Before the first armistice was signed, President McKinley sent directives to the Secretary of War on July 13, 1898 regarding occupations by U.S. troops during the war. This prompted the Secretary of War to publish General Orders No. 101 and was provided to all commanders of U.S. troops, to include the commander of troops that occupied the Hawaiian Kingdom, which took place on August 12, 1898, one year before the armistice was signed suspending hostilities in the Philippines. General Orders No. 101 clearly reflects the United States recognition of customary international law regarding the law of occupation, which are the same provisions codified in the 1899 Hague Convention, II.

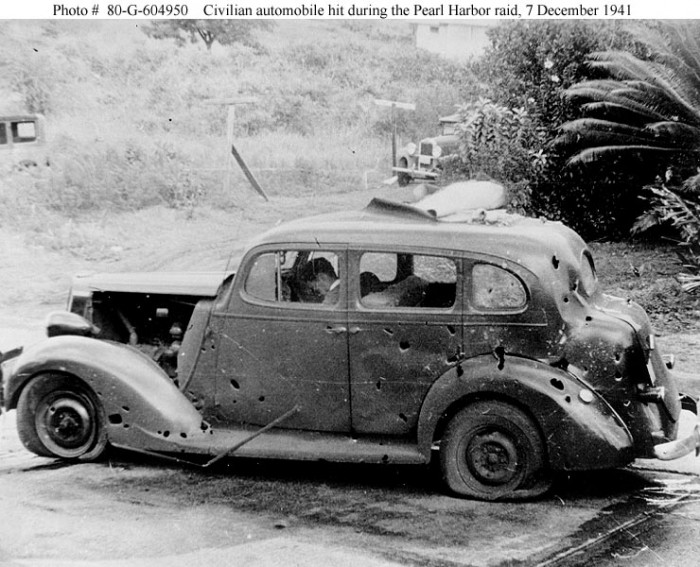

The commanders of U.S. troops occupying the Hawaiian Kingdom since August 12, 1898 disregarded General Orders No. 101. The failure of the commanders of U.S. troops in the Hawaiian Kingdom to comply with General Orders No. 101 and international humanitarian law, to include its current commander of the U.S. Pacific Command, Admiral Locklear, is why war crimes have and continue to be committed on a monumental scale.

The commanders of U.S. troops occupying the Hawaiian Kingdom since August 12, 1898 disregarded General Orders No. 101. The failure of the commanders of U.S. troops in the Hawaiian Kingdom to comply with General Orders No. 101 and international humanitarian law, to include its current commander of the U.S. Pacific Command, Admiral Locklear, is why war crimes have and continue to be committed on a monumental scale.

In 2012, Admiral Locklear was notified by attorney Dexter Kaiama that war crimes are being committed in the courts of the State of Hawai‘i. Kaiama’s protest and demand stated:

In 2012, Admiral Locklear was notified by attorney Dexter Kaiama that war crimes are being committed in the courts of the State of Hawai‘i. Kaiama’s protest and demand stated:

“As the Commander of the U.S. Pacific Command, your office is the direct extension of the United States President in the Hawaiian Islands through the Secretary of Defense. As the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to remain an independent and sovereign State, the Lili‘uokalani assignment and Article 43 of the 1907 Hague Convention IV mandates your office to administer Hawaiian Kingdom law in accordance with international law and the laws of occupation. The violations of my client’s right to a fair and regular trial are directly attributable to the President’s failure, and by extension your office’s failure, to comply with the Lili‘uokalani assignment and Article 43 of the 1907 Hague Convention, IV, which makes this an international matter.”

Although Admiral Locklear disregarded the protest and demand, he cannot claim he wasn’t aware. In order for a person to have committed a war crime, the perpetrator must be aware of the alleged war crimes and possesses the criminal element of intent—mens rea (criminal intent), in the commission of the war crime—actus reus (the guilty act). Defenses to criminal liability include mistake of fact and mistake of law.

According to Article 30(1) of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, the defendant is “criminally responsible and liable for punishment…only if the material elements [of the war crime] are committed with intent and knowledge.” Therefore, the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court will prosecute if there is a mental element that includes a volitional component (intent) as well as a cognitive component (knowledge). Article 30(2) further clarifies that “a person has intent where: (a) In relation to conduct, that person means to engage in the conduct; [and] (b) In relation to a consequence, that person means to cause that consequence or is aware that it will occur in the ordinary course of events.”

With regard to knowledge, Article 30(3) of the Rome Statute provides that “‘knowledge’ means awareness that a circumstance exists or a consequence will occur in the ordinary course of events.” “A mistake of fact,” according Article 32(1), “shall be a ground for excluding criminal responsibility only if it negates the mental element required by the crime,” and a “mistake of law,” according to Article 32(2), “shall not be a ground for excluding criminal responsibility [unless] …it negates the mental element required by such a crime, or as provided for in article 33.” Article 33 provides that a crime that “has been committed by a person pursuant to an order of a Government or of a superior, whether military or civilian, shall not relieve that person of criminal responsibility unless: (a) the person was under a legal obligation to obey orders of the Government or the superior in question; (b) the person did not know that the order was unlawful; and (c) the order was not manifestly unlawful.”

General Orders No. 101 is a lawful order that has not been complied with for over a century and the excuse that the Order is not relevant because the U.S. Congress annexed the Hawaiian Islands by a joint resolution of annexation on July 7, 1898 is also a violation of customary international law previously recognized by the United States. Not only are municipal laws incapable of annexing foreign territory because municipal laws are confined  to the territory of the country that enacted them, U.S. Attorney General Thomas Bayard in 1887 famously stated, “If a government could set up its own municipal law as the final test of its international rights and obligations, then the rules of international law would be but the shadow of a name, and would afford not protection either to states or to individuals. It has been constantly maintained and also admitted by the Government of the United States that a Government can not appeal to its municipal regulations as an answer to demands for the fulfillment of international duties.”

to the territory of the country that enacted them, U.S. Attorney General Thomas Bayard in 1887 famously stated, “If a government could set up its own municipal law as the final test of its international rights and obligations, then the rules of international law would be but the shadow of a name, and would afford not protection either to states or to individuals. It has been constantly maintained and also admitted by the Government of the United States that a Government can not appeal to its municipal regulations as an answer to demands for the fulfillment of international duties.”

Attorney General Bayard’s statement was the United States’ recognition of what was considered customary international law, at least in 1887. This customary international law was codified in the 1980 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. Article 27 provides, “A party may not invoke the provisions of its internal law as justification for its failure to perform a treaty.” These treaties include the 1907 Hague Convention, IV, and the 1949 Geneva Convention, IV, which the United States ratified and recognized as customary international laws. Although the United States has not ratified the Vienna Convention, it does consider it to be customary international law. According to the U.S. State Department website, “The United States considers many of the provisions of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties to constitute customary international law on the law of treaties.”

General Orders No. 101 is still binding.