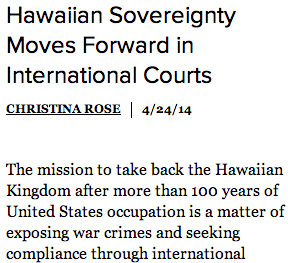

After the Office of Hawaiian Affairs CEO Dr. Kamana‘opono Crabbe submitted a formal request to Secretary of State John Kerry seeking clarification on the legal status of Hawai‘i under international law, all nine OHA Trustees yesterday signed a letter to the Secretary of State, stating:

After the Office of Hawaiian Affairs CEO Dr. Kamana‘opono Crabbe submitted a formal request to Secretary of State John Kerry seeking clarification on the legal status of Hawai‘i under international law, all nine OHA Trustees yesterday signed a letter to the Secretary of State, stating:

“We understand that you received a letter from Office of Hawaiian Affairs Chief Executive Officer Kamana‘opono M. Crabbe, PhD dated May 5, 2014. The contents of that letter do not reflect the position of the Board of Trustees of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs or the position of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. That letter is hereby rescinded.”

Did the Trustees even read Dr. Crabbe’s letter? How do you rescind a letter that seeks clarification for risk management purposes. You can’t. The only person that can rescind the letter is the CEO himself, and only when the risks identified have been found to not be risks in the first place. Another word for this is fiduciary duty.

This morning’s front page article in the Star-Advertiser reported that Trustee Chairwoman Colette Machado said “Crabbe exceeded his authority as chief executive officer that requires him to consult the board on such matters.” Is Dr. Crabbe’s request for clarification a management issue or a board issue. Does the CEO need Board approval to ask questions? What is the position of the Board of Trustees of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs? We don’t want clarification? The so-called rescind letter is not only odd, but it is disingenuous and has nothing to do with Dr. Crabbe’s letter. It also raises the question of who is pulling the strings.

This morning’s front page article in the Star-Advertiser reported that Trustee Chairwoman Colette Machado said “Crabbe exceeded his authority as chief executive officer that requires him to consult the board on such matters.” Is Dr. Crabbe’s request for clarification a management issue or a board issue. Does the CEO need Board approval to ask questions? What is the position of the Board of Trustees of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs? We don’t want clarification? The so-called rescind letter is not only odd, but it is disingenuous and has nothing to do with Dr. Crabbe’s letter. It also raises the question of who is pulling the strings.

After carefully reviewing Dr. Crabbe’s letter, he did not state or even imply that he was taking any position on whether or not the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist. He merely sought clarification on a legal issue that the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel is more than capable of answering. If there is any position taken by Dr. Crabbe its responsible management and the well-recognized principle “risk management.” His letter begins with:

“As the chief executive officer and administrator for the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, being a governmental agency of the State of Hawai‘i, the law places on me, as a fiduciary, strict standards of diligence, responsibility and honesty. My executive staff, as public officials, carry out the policies and directives of the Trustees of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs in the service of the Native Hawaiian community. We are responsible to take care, through all lawful means, that we apply the best skills and diligence in the servicing of this community. It is in this capacity and in the interest of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs I am submitting this communication and formal request.”

The performance of risk assessment begins with identification of risks. Once the risk or risks have been determined the management can choose to avoid the risk, reduce the risk, share the risk or retain the risk. After the option is made, management then calls for a plan for contingencies, create safeguards, and, lastly, to monitor.

Dr. Crabbe has clearly taken the path to avoid the risk by seeking clarification from the State Department and the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel.

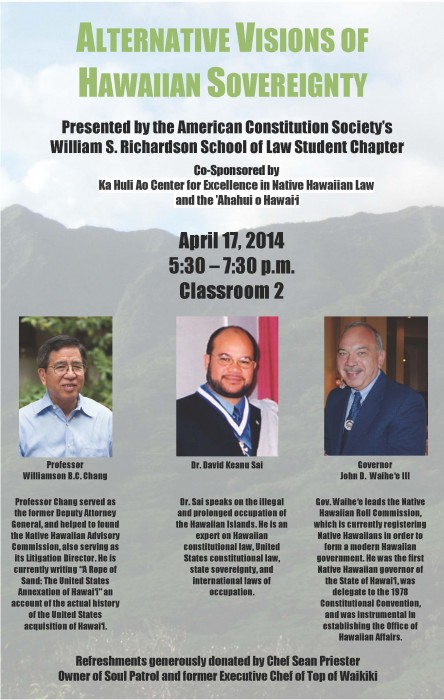

From his letter he specifically states the risks began to surface when one of his executive managers attended a presentation and panel discussion at the University of Hawai‘i Law School featuring former Hawai‘i governor John Waihe‘e, III, senior Law Professor Williamson Chang and political scientist Dr. Keanu Sai. The law student chapter of the American Constitutional Society sponsored the presentation. Dr. Crabbe provided Secretary of State Kerry an online link to view the video of the law school presentation.

https://vimeo.com/92655472

Crabbe wrote, “The presentations of Professor Chang and Dr. Sai provided a legal analysis of the current status of Hawai‘i that appeared to undermine the legal basis of the Roll Commission, and, as alleged in the panel discussions, the possibility of criminal liability under international law. Both Professor Chang and Dr. Sai specifically stated that the Federal and State of Hawai‘i governments are illegal regimes that stem from an illegal and prolonged occupation by the United States as a result of the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government. As a government agency of the State of Hawai‘i this would include the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, and by enactment of the State of Hawai‘i Legislature, it would also include the Roll Commission. Both Act 195 and U.S. Public Law 103-150, acknowledges the illegality of the overthrow.”

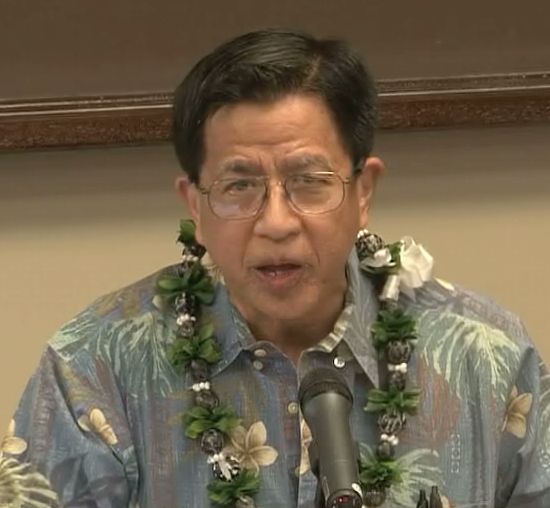

Here are some quotes from senior Law Professor Chang:

Here are some quotes from senior Law Professor Chang:

“The power of the United States, over the Hawaiian islands, and the jurisdiction of the United States in the State of Hawai’i, by its own admissions, by its own laws, doesn’t exist. And so that means that ever since the 1898 annexation of Hawai’i, by a Joint Resolution, they say, we have been living a myth.” (3:01 min/sec.)

“If you don’t have legal power over a territory, you’re governing without jurisdiction.” (4:20 min/sec.)

“…there’s no treaty between the United States and Hawai‘i by which Hawai‘i was acquired by the United States…” (4:41 min/sec.)

“A joint resolution, as an act of Congress, cannot acquire another country …If the United States could acquire Hawai‘i then the House of Nobles and the Legislative Assembly of Hawai‘i could acquire the United States.” (4:54 min/sec.)

“If two sovereigns are equal … one cannot acquire the other by its own laws.” (5:17 min/sec.)

“If Congress cannot, by Joint Resolution in 1898, acquire Hawai‘i unilaterally, it cannot do so in 1959.” (9:42 min/sec.)

“So in short, the United States by its own hands admits that it didn’t acquire the Hawaiian Islands, and all those Hawaiians, who have been saying the United States doesn’t have jurisdiction, have been right.” (11:25 min/sec.)

“So the annexation, that we all admit that nothing can be achieved without the United States going along with it, that’s the 900 lbs. elephant in the room. But we have to come in with the best leverage we have, and the best leverage we have is a hundred years of being lied to, being misrepresented, being told that we were part of the United States, and that has been legally false.” (17:19 min/sec.)

“…we’re all in this boat together in this journey of knowledge, and when I talk about the state of emergency, being the United States, how it is able to govern us for a hundred years without putting guns to our heads, it’s us. We’re the problem, the law school is the problem. Why, because judges and lawyers have a duty of candor and truth. Judges, on their own, have to tell the courts, tell the attorneys that there is no jurisdiction. It’s a duty of zealous representation for attorneys to present the best defense, and isn’t it the best defense that there’s no jurisdiction.” (1:36:41 hr/min/sec.)

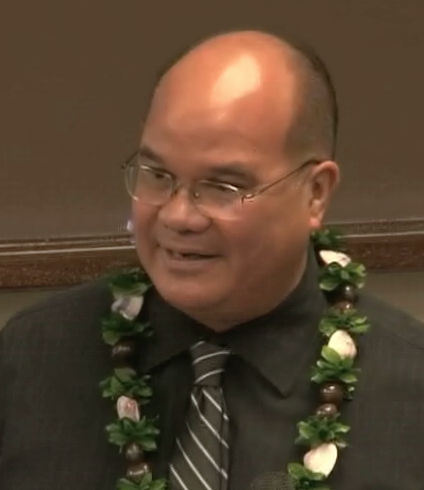

Here some quotes from political scientist Dr. Keanu Sai:

Here some quotes from political scientist Dr. Keanu Sai:

“Without a treaty, the United States has enacted “internal laws,” by its Congress, imposed in Hawai‘i…1898 Joint Resolution of Annexation, 1900 Territorial Act, 1959 Statehood Act, 1993 Joint Resolution of Apology for the 1893 Overthrow” (1:37:17 hr/min/sec.)

“Now the first and foremost restriction imposed by international law upon a State is that it may not exercise its power in any form in the territory of another State. In this sense jurisdiction is certainly territorial; it cannot be exercised by a State outside of its territory except by virtue of a permissive rule derived from international custom or from a convention.” (1:36:53 hr/min/sec.)

“military occupation confers upon the invading force the means of exercising control for the period of occupation. It does not transfer the sovereignty to the occupant, but simply the authority or power to exercise some of the rights of sovereignty.” (1:13:19 hr/min/sec.)

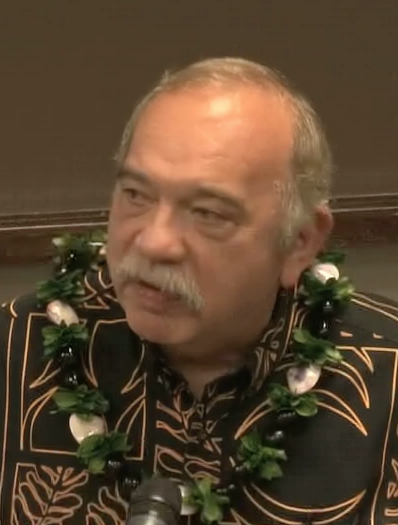

Even former governor and chairman of the Native Hawaiian Roll Commission Waihe‘e was in agreement with Dr. Sai’s analysis that Hawai‘i is not a part of the United States. Waihe‘e told the audience:

Even former governor and chairman of the Native Hawaiian Roll Commission Waihe‘e was in agreement with Dr. Sai’s analysis that Hawai‘i is not a part of the United States. Waihe‘e told the audience:

“I have absolutely no doubt that Hawai‘i is in an illegal occupation, I have absolutely no doubt. I mean, you’ve got to be illiterate not to finally get to that point.” (1:19:04 hr/min/sec.)

Can a CEO of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs take this lightly, especially when the Chairman of the Native Hawaiian Roll Commission himself stated he has no doubt that Hawai‘i is occupied and that you’ve got to be illiterate to not see it. Dr. Crabbe correctly states:

“These matters have raised grave concerns with regard to not only the Native Hawaiian community we serve, but also to the vicarious liability of myself, staff and Trustees of the Hawaiian Affairs, and members of the Native Hawaiian Roll Commission. The community we serve, the Trustees, and many of my staff members, to include myself, and the members of the Roll Commission are Native Hawaiians, who are direct descendants of Hawaiian subjects of the Hawaiian Kingdom. And as a State of Hawai‘i governmental agency, it would also appear that I am precluded from seeking any opinion on the veracity of these allegations from our in house counsel or from the State of Hawai‘i Attorney General, because there would appear to exist a conflict of interest if these allegations are true.”

Dr. Crabbe then provided the questions he’s seeking to be answered as part of the process of risk management.

• First, does the Hawaiian Kingdom, as a sovereign independent State, continue to exist as a subject of international law?

• Second, if the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist, do the sole-executive agreements bind the United States today?

• Third, if the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist and the sole-executive agreements are binding on the United States, what effect would such a conclusion have on United States domestic legislation, such as the Hawai‘i Statehood Act, 73 Stat. 4, and Act 195?

• Fourth, if the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist and the sole-executive agreements are binding on the United States, have the members of the Native Hawaiian Roll Commission, Trustees and staff of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs incurred criminal liability under international law?”

Dr. Crabbe’s conclusion in his letter clearly speaks to risk management and his determination to avoid the risk of criminal liability under international law. He stated, “While I await the opinion from the Office of Legal Counsel, I will be requesting approval from the Trustees of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs that we refrain from pursuing a Native Hawaiian governing entity until we can confirm that the Hawaiian Kingdom, as an independent sovereign State, does not continue to exist under international law and that we, as individuals, have not incurred any criminal liability in this pursuit.”

At no point has Dr. Crabbe taken a position for the Office of Hawaiian Affairs and nor has he taken a position of whether the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist. He’s seeking clarification from a federal agency who is more than capable of providing the answers. As chief executive officer, Dr. Crabbe is responsible for the protection of the staff at the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, which includes the Trustees, and to the Native Hawaiian community OHA serves. The Trustees’ so-called rescind letter is a blatant attempt to undermine the very duty Dr. Crabbe was appointed to do as the CEO of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. The Trustees’ do not manage the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, the CEO does.

The irony is that Dr. Crabbe’s request for clarification is to protect the Trustees, even from themselves.