PRESS RELEASE

For immediate release – 17 July 2018

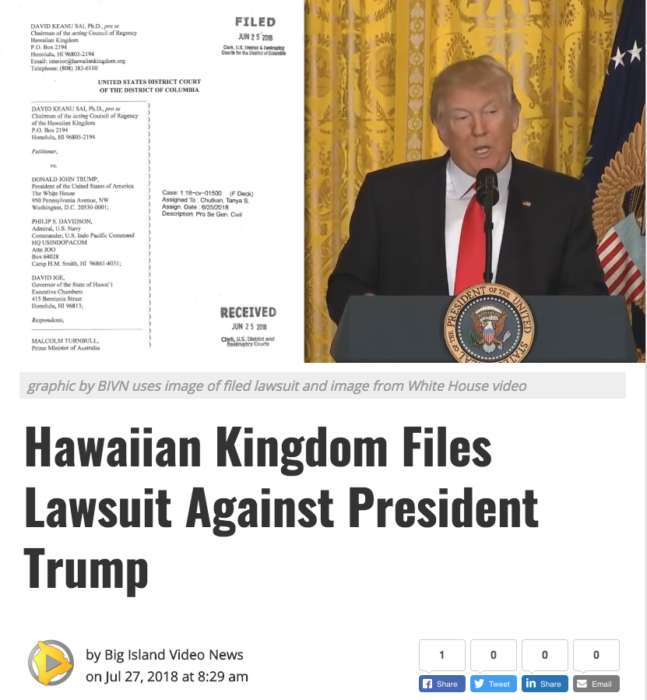

Petition for an Emergency Writ of Mandamus filed with U.S. Federal District Court in Washington, D.C., against President Trump regarding the prolonged American occupation of the Hawaiian Islands

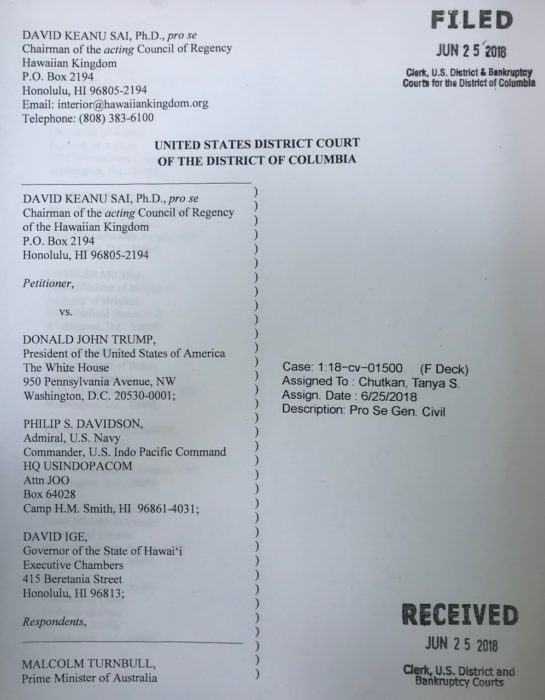

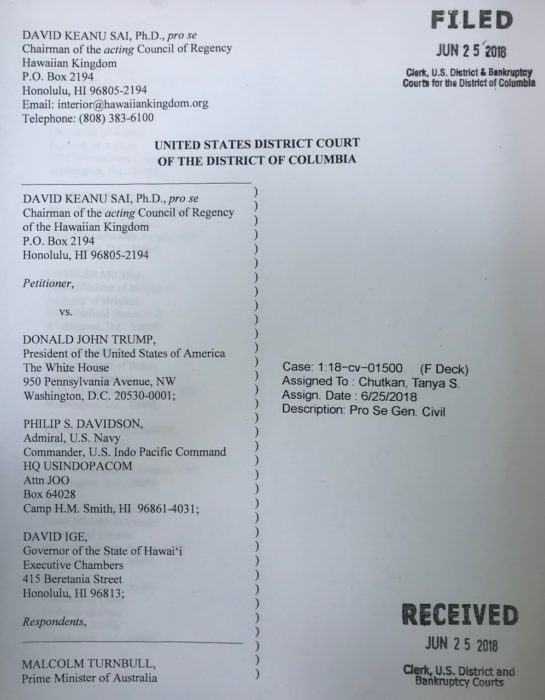

[David Keanu Sai vs. Donald John Trump et. al, Case: 1:18-cv-01500]

HONOLULU, 17 July 2018 — On Monday morning, 25 June 2018, the Chairman of the acting Council of Regency for the Hawaiian Kingdom, H.E. David Keanu Sai, Ph.D., filed with the United States District Court for the District of Columbia a Petition for an Emergency Writ of Mandamus against President Donald John Trump. This Petition concerns the illegal and prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Islands and the failure of the United States to administer the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom as mandated under Article 43 of the 1907 Hague Convention, IV, Respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land (36 Stat. 2199) and under Article 64 of the 1949 Geneva Convention, IV, Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War (6 U.S.T. 3516). The United States has ratified both treaties. The case has been assigned to Judge Tanya S. Chutkan under civil case no. 1:18-cv-01500.

Under American rules of civil procedure, a petition for writ of mandamus is an administrative remedy that seeks to compel an officer or employee of the United States or any of its agencies to fulfill their official duties. It is not a complaint alleging certain facts to be true. The Hague and Geneva Conventions obligates the United States, as an occupying State, to administer the laws of the occupied State. There is no discretion on this duty to administer Hawaiian Kingdom law. This duty is mandated under international humanitarian law.

Furthermore, according to the U.S. Constitution, treaties, such as the Hague and Geneva Conventions, are the supreme law of the land, and the United States is bound by them just as they are bound by the U.S. Constitution or any of the laws enacted by the Congress. Consequently, the failure of the United States to administer Hawaiian Kingdom laws has created a humanitarian crisis of unimaginable proportions where war crimes have and continue to be committed with impunity. War crimes have no statutes of limitation.

The Petition mentions Iraq’s violation of international humanitarian law when it invaded Kuwait on 2 August 1990, and, like the United States, did not administer Kuwaiti law as mandated by the Hague and Geneva Conventions. This led to the formation of the United Nations Compensation Commission (UNCC) by the United Nations Security Council under resolution 687 (1991). The mandate of the UNCC was to process claims and pay compensation for losses or damages incurred as a direct result of Iraq’s unlawful invasion and occupation of Kuwait. In total, the UNCC awarded $52.4 billion dollars for an unlawful occupation that lasted seven months. If this formula is applied to the unlawful invasion and occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom since 16 January 1893 that compensation amount would be staggering.

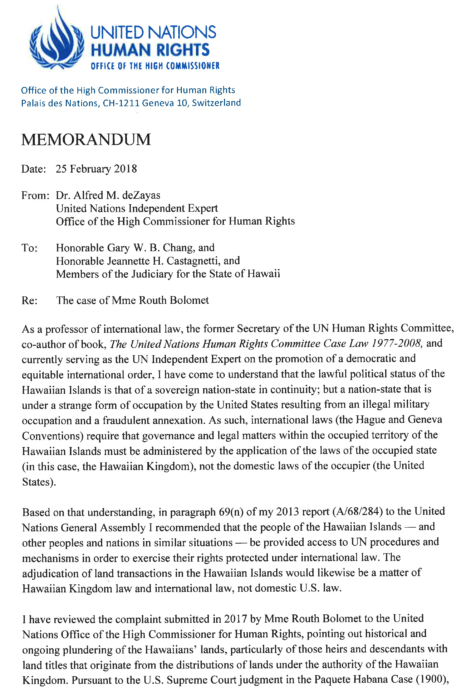

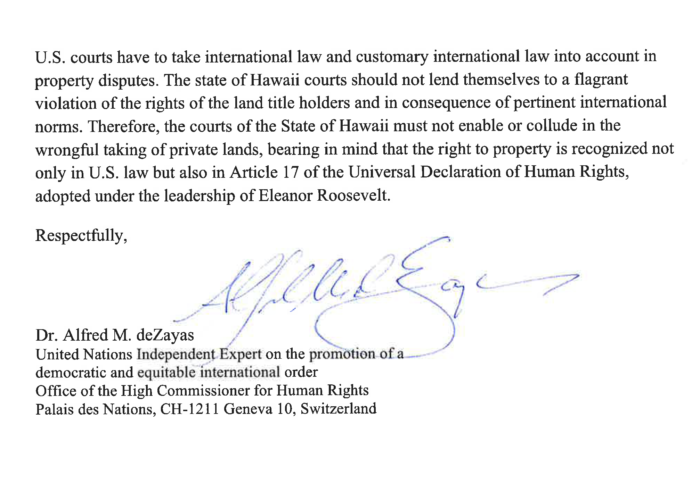

This law suit comes on the heels of a memorandum, dated 25 February 2018, by the United Nations Independent Expert, Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, to the members of the judiciary of the State of Hawai‘i. The memo’s author, Dr. Alfred deZayas, who served as the Independent Expert until he retired on 30 April 2018, stated:

“As a professor of international law, the former Secretary of the UN Human Rights Committee, co-author of book, The United Nations Human Rights Committee Case Law 1977-2008, and currently serving as the UN Independent Expert on the promotion of a democratic and equitable international order, I have come to understand that the lawful political status of the Hawaiian Islands is that of a sovereign nation-state in continuity; but a nation-state that is under a strange form of occupation by the United States resulting from an illegal military occupation and a fraudulent annexation. As such, international laws (the Hague and Geneva Conventions) require that governance and legal matters within the occupied of the Hawaiian Islands must be administered by the application of the laws of the occupied state (in this case, the Hawaiian Kingdom), not the domestic laws of the occupier (the United States).”

In the Petition, the Hawaiian Kingdom begins with a preliminary statement concerning international proceedings held at the Permanent Court of Arbitration, The Hague, Netherlands.

“When the South China Sea Tribunal cited in its award on jurisdiction the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom case held at the Permanent Court of Arbitration (“PCA”), that should have garnered international attention, especially after the PCA acknowledged the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent state and not the fiftieth State of the United States of America. The Larsen case was a dispute between a Hawaiian national and his government, who he claimed was negligent for allowing the unlawful imposition of American laws over Hawaiian territory that led to the alleged war crimes of unfair trial, unlawful confinement and pillaging.”

Chairman Sai served as Agent for the Hawaiian government in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, PCA Case no. 1999-01. Before forming the ad hoc tribunal, the PCA acknowledged the Hawaiian Kingdom’s continued existence as an independent State and that the Hawaiian Kingdom would access the jurisdiction of the PCA as a non-Contracting Power pursuant to Article 47 of the 1907 Hague Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes.

Chairman Sai stated, “the United States, as an occupier, is mandated to administer Hawaiian Kingdom law over Hawaiian territory and not its own, until they withdraw. This is not a mere descriptive assumption by the occupying State, but rather it is the law of occupation. And this was precisely what the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom arbitration was founded on—the unlawful imposition of American laws.” In 2001, Bederman and Hilbert reported in the American Journal of International Law:

“At the center of the PCA proceedings was…that the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist and that the Hawaiian Council of Regency (representing the Hawaiian Kingdom) is legally responsible under international law for the protection of Hawaiian subjects, including the claimant. In other words, the Hawaiian Kingdom was legally obligated to protect Larsen from the United States’ “unlawful imposition [over him] of [its] municipal laws” through its political subdivision, the State of Hawaii. As a result of this responsibility, Larsen submitted, the Hawaiian Council of Regency should be liable for any international law violations that the United States had committed against him.”[1]

The Tribunal was comprised of three renowned international jurists, namely, Judge James Crawford, SC, current member of the International Court of Justice, Judge Christopher Greenwood, QC, former member of the International Court of Justice, and Dr. Gavan Griffith, former Australian Solicitor General.

Larsen sought to have the Tribunal adjudge that the United States had violated his rights. He then sought the Tribunal to adjudge that the Hawaiian government was liable for those violations. Although the United States was formally invited, by the Hawaiian government, to join in the arbitration on 3 March 2000, it chose not to. The United States absence thus raised the indispensable third-party rule for Larsen to overcome. In its award (para. 7.4), however, the Tribunal acknowledged the Hawaiian Kingdom’s lawful political status since the nineteenth century.

“[I]n the nineteenth century the Hawaiian Kingdom existed as an independent State recognized as such by the United States of America, the United Kingdom and various other States, including by exchanges of diplomatic or consular representatives and the conclusion of treaties.”

After returning from oral hearings held at The Hague in December of 2000, the Council of Regency adopted a policy of education and exposure of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s lawful political status as an independent State. The Council made this decision to address the American policy of denationalization—Americanization that was implemented throughout the schools in the islands since 1906. Denationalization is a war crime. Within three generations, Americanization had effectively obliterated the national consciousness of the Hawaiian Kingdom in the minds of Hawai‘i’s people. This denationalization has resulted in a common misunderstanding that since President Barrack Obama was born in Hawai‘i, he was born within the United States. He was not. He was born in the Hawaiian Kingdom to an American mother and a Kenyan father. As such, he was born an American citizen by parentage—jus sanguinis, but not as a natural born citizen—jus soli.

It would take 18 years of education and exposure to prompt the Hawaiian government to file the Petition for Emergency Writ of Mandamus. The Petition was filed with the Federal Court in accordance with 28 U.S.C. §1331 (federal question jurisdiction), 28 U.S.C. §1651(a) (writ of mandamus), and 5 U.S.C. §702 (waiver of sovereign immunity). The Petition also names as nominal respondents twenty-eight countries that had diplomatic relations with the Hawaiian Kingdom to include treaties, and five international agencies. All of the respondents received a copy of the filed Petition, through the United States Postal Service, with a cover letter noting that a summons would be forthcoming.

They include the United States, the Indo-Pacific Command, the State of Hawai‘i, Australia, Austria, the Bahamas, Belgium, Belize, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, Cuba, France, Germany, Guatemala, Hungary, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Peru, Portugal, Russia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. Also included was the United Nations Secretary General, the President of the United Nations General Assembly, the President of the United Nations Security Council, the President of the United Nations Human Rights Committee, and the Chairman of the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s Administrative Council.

In his letter to the United Nations Secretary General, Chairman Sai invoked the law of State responsibility. Chairman Sai stated:

“As an internationally wrongful act, all States shall not ‘recognize as lawful a situation created by a serious breach within the meaning of Article 40, nor render aid or assistance in maintaining that situation (Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts, 2001),’ Article 40 provides that a ‘breach of such an obligation is serious if it involves a gross or systemic failure by the responsible State to fulfill the obligation.’ By letter to United States President Donald John Trump dated 5 July 2018, the Hawaiian Kingdom gave notice of claim and invoked responsibility of the United States, in accordance with Article 43, for a serious breach of an obligation to comply with international humanitarian law.”

Chairman Sai then made the following request to the Secretary General:

“As a State not a member of the United Nations, but a member of the Universal Postal Union since 1882, being a specialized agency of the United Nations, I should be grateful if you would have this letter and the full text of its enclosures circulated as an official document of the General Assembly and of the Security Council.”

The United States has been in an illegal state of war against the Hawaiian Kingdom since 1893

On 9 March 1893, President Grover Cleveland, at the request of Queen Lili‘uokalani, conducted an investigation into the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government that occurred on 17 January 1893. Her Majesty notified the President that the overthrow of her government was committed by the United States diplomat assigned to the Hawaiian Kingdom, John Stevens, and by the unauthorized landing of United States armed forces.

President Cleveland appointed James Blount, former Chairman of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, as Special Commissioner. Commissioner Blount arrived in Honolulu on 31 March 1893 and initiated his investigation the following day. After sending periodical reports to Secretary of State Walter Gresham in Washington, D.C., Blount completed his final report on 17 July 1893. On 18 October 1893, Gresham submitted his report to the President. Gresham concluded:

“The Government of Hawaii surrendered its authority under a threat of war, until such time only as the Government of the United States, upon the facts being presented to it, should reinstate the constitutional sovereign… Should not the great wrong done to a feeble but independent State by an abuse of the authority of the United States be undone by restoring the legitimate government? Anything short of that will not, I respectfully submit, satisfy the demands of justice.”

The following month, on 18 December 1893, President Grover Cleveland notified the Congress of the findings and conclusions of his investigation. President Cleveland stated:

“And so it happened that on the 16th day of January, 1893, between four and five o’clock in the afternoon, a detachment of marines from the United States steamer Boston, with two pieces of artillery, landed at Honolulu. The men, upwards of 160 in all, were supplied with double cartridge belts filled with ammunition and with haversacks and canteens, and were accompanied by a hospital corps with stretchers and medical supplies. This military demonstration upon the soil of Honolulu was of itself an act of war, unless made either with the consent of the Government of Hawaii or for the bona fide purpose of protecting the imperiled lives and property of citizens of the United States. But there is no pretense of any such consent on the part of the Government of the Queen, which at the time was undisputed and was both the de facto and the de jure government. In point of fact the existing government instead of requesting the presence of an armed force protested against it.”

The President concluded:

“By an act of war, committed with the participation of a diplomatic representative of the United States and without authority of Congress, the Government of a feeble but friendly and confiding people has thus been overthrown. A substantial wrong has thus been done which a due regard for our national character as well as the rights of the injured people requires we should endeavor to repair.”

When President Cleveland concluded that by an act of war committed against the Hawaiian Kingdom on 16 January 1893, which led to the unlawful overthrow of the Hawaiian government the following day, he acknowledged the situation under international law transformed from a state of peace to a state of war. Only by way of a treaty of peace could a state of war be transformed back to a state of peace. To explain this transformation, Chairman Sai, as Hawaiian Ambassador-at-large, authored a memorandum titled The Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom Case at the Permanent Court of Arbitration and Why There Is An Ongoing Illegal State of War with the United States of America Since 16 January 1893 (16 October 2017). This memorandum has been translated into Farsi, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Russian and Spanish.

On the very same day the President notified the Congress of the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian government, an agreement of restoration and peace was negotiated between the new U.S. diplomat assigned to the Hawaiian Kingdom, Albert Willis, and the Queen. Negotiations began on 13 November and lasted until 18 December 1893. However, due to political wrangling going on in the Congress, the President was unable to fulfill the United States’ obligation under the agreement of peace with the Queen. Five years later in 1898, the United States fraudulently annexed the Hawaiian Islands during the Spanish-American war and fortified it as a military outpost. Hawai‘i currently serves as headquarters for the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command.

In 2013, the New York Times reported North Korea’s announcement that “all of its strategic rocket and long range artillery units ‘are assigned to strike bases of the U.S. imperialist aggressor troops in the U.S. mainland and on Hawaii.” The Hawaiian Kingdom’s existential threat has been heightened today by the rhetoric of U.S. President Donald Trump and North Korea’s Kim Jong-un.

Instead of establishing a system to administer Hawaiian Kingdom law in 1893, the United States maintained their installed insurgency, calling itself the Provisional government, who, under the protection of U.S. troops, unlawfully seized control of the Hawaiian government apparatus. In 1894, these insurgents renamed themselves as the Republic of Hawai‘i. Six years later, the U.S. Congress changed that name to the Territory of Hawai‘i. And in 1959, Congress changed that name to the State of Hawai‘i. The U.S. Congress could no more establish a government in the Hawaiian Kingdom by enacting domestic statutes, than it could establish a government in Germany or in the United Kingdom.

Since the United States’ admitted unlawful overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government in 1893, there has been no lawful government in the Hawaiian Islands until the Hawaiian Council of Regency was established in 1995. The unlawful overthrow of the Hawaiian government 125 years ago, however, did not affect the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State under international law. The Hawaiian Kingdom continued to remain in existence just as Iraq continued to exist despite its government being overthrown in 2003 by United States armed forces.

###

[1] David Bederman & Kurt Hilbert, “Arbitration—UNCITRAL Rules—justiciability and indispensible third parties—legal status of Hawaii,” 95 American Journal of International Law (2001) 927, at 928.

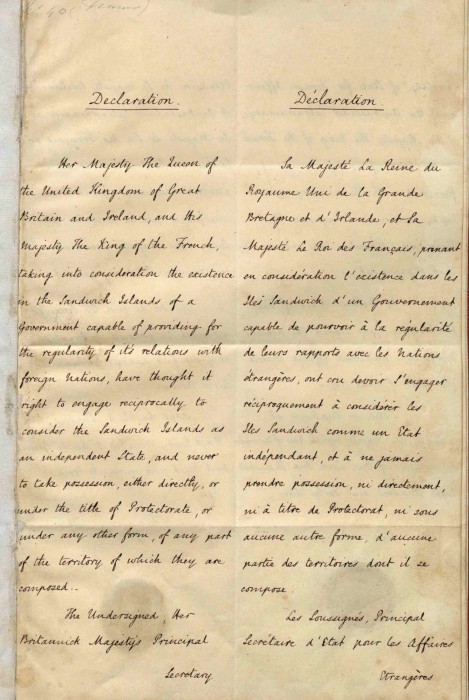

In the summer of 1842, Kamehameha III moved forward to secure the position of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a recognized independent state under international law. He sought the formal recognition of Hawaiian independence from the three naval powers of the world at the time—Great Britain, France, and the United States. To accomplish this, Kamehameha III commissioned three envoys, Timoteo Ha‘alilio, William Richards, who at the time was still an American Citizen, and Sir George Simpson, a British subject. Of all three powers, it was the British that had a legal claim over the Hawaiian Islands through cession by Kamehameha I, but for political reasons the British could not openly exert its claim over the other two naval powers. Due to the islands prime economic and strategic location in the middle of the north Pacific, the political interest of all three powers was to ensure that none would have a greater interest than the other. This caused Kamehameha III “considerable embarrassment in managing his foreign relations, and…awakened the very strong desire that his Kingdom shall be formally acknowledged by the civilized nations of the world as a sovereign and independent State.”

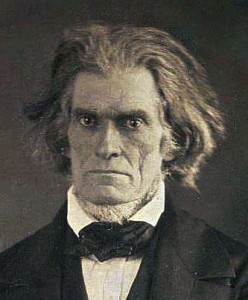

In the summer of 1842, Kamehameha III moved forward to secure the position of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a recognized independent state under international law. He sought the formal recognition of Hawaiian independence from the three naval powers of the world at the time—Great Britain, France, and the United States. To accomplish this, Kamehameha III commissioned three envoys, Timoteo Ha‘alilio, William Richards, who at the time was still an American Citizen, and Sir George Simpson, a British subject. Of all three powers, it was the British that had a legal claim over the Hawaiian Islands through cession by Kamehameha I, but for political reasons the British could not openly exert its claim over the other two naval powers. Due to the islands prime economic and strategic location in the middle of the north Pacific, the political interest of all three powers was to ensure that none would have a greater interest than the other. This caused Kamehameha III “considerable embarrassment in managing his foreign relations, and…awakened the very strong desire that his Kingdom shall be formally acknowledged by the civilized nations of the world as a sovereign and independent State.” While the envoys were on their diplomatic mission, a British Naval ship, HBMS Carysfort, under the command of Lord Paulet, entered Honolulu harbor on February 10, 1843, making outrageous demands on the Hawaiian government. Basing his actions on complaints made to him in letters from the British Consul, Richard Charlton, who was absent from the kingdom at the time, Paulet eventually seized control of the Hawaiian government on February 25, 1843, after threatening to level Honolulu with cannon fire. Kamehameha III was forced to surrender the kingdom, but did so under written protest and pending the outcome of the mission of his diplomats in Europe. News

While the envoys were on their diplomatic mission, a British Naval ship, HBMS Carysfort, under the command of Lord Paulet, entered Honolulu harbor on February 10, 1843, making outrageous demands on the Hawaiian government. Basing his actions on complaints made to him in letters from the British Consul, Richard Charlton, who was absent from the kingdom at the time, Paulet eventually seized control of the Hawaiian government on February 25, 1843, after threatening to level Honolulu with cannon fire. Kamehameha III was forced to surrender the kingdom, but did so under written protest and pending the outcome of the mission of his diplomats in Europe. News  of Paulet’s action reached Admiral Richard Thomas of the British Admiralty, and he sailed from the Chilean port of Valparaiso and arrived in the islands on July 25, 1843. After a meeting with Kamehameha III, Admiral Thomas determined that Charlton’s complaints did not warrant a British takeover and ordered the restoration of the Hawaiian government, which took place in a grand ceremony on July 31, 1843. At a thanksgiving service after the ceremony, Kamehameha III proclaimed before a large crowd, ua mau ke ea o ka ‘aina i ka pono (the life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness). The King’s statement became the national motto.

of Paulet’s action reached Admiral Richard Thomas of the British Admiralty, and he sailed from the Chilean port of Valparaiso and arrived in the islands on July 25, 1843. After a meeting with Kamehameha III, Admiral Thomas determined that Charlton’s complaints did not warrant a British takeover and ordered the restoration of the Hawaiian government, which took place in a grand ceremony on July 31, 1843. At a thanksgiving service after the ceremony, Kamehameha III proclaimed before a large crowd, ua mau ke ea o ka ‘aina i ka pono (the life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness). The King’s statement became the national motto.

On May 10, 2018, Mrs. Routh Bolomet, a Hawaiian-Swiss citizen, provided Dr. Keanu Sai with a remarkable document that came out of the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights in Geneva, Switzerland, regarding Hawai‘i. Mrs. Bolomet told Dr. Sai that it was her hope that the document authored by

On May 10, 2018, Mrs. Routh Bolomet, a Hawaiian-Swiss citizen, provided Dr. Keanu Sai with a remarkable document that came out of the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights in Geneva, Switzerland, regarding Hawai‘i. Mrs. Bolomet told Dr. Sai that it was her hope that the document authored by  The President of the Council,

The President of the Council,

His memorandum also serves as an amendment to the 2013 Report correcting the legal status of Hawai‘i as an occupied State and not an issue of self-determination for an indigenous group of people. In line with this change, Article 69(e) of his recommendations is more appropriate, “States should ratify the individual complaints procedures of the United Nations human rights treaties, adhere to and utilize the inter-State complaints procedures, and globalize the reach of the International Criminal Court.”

His memorandum also serves as an amendment to the 2013 Report correcting the legal status of Hawai‘i as an occupied State and not an issue of self-determination for an indigenous group of people. In line with this change, Article 69(e) of his recommendations is more appropriate, “States should ratify the individual complaints procedures of the United Nations human rights treaties, adhere to and utilize the inter-State complaints procedures, and globalize the reach of the International Criminal Court.”

This process, which is known as Americanization and which is a war crime, has nearly obliterated the national consciousness of the Hawaiian Kingdom in the minds of Hawai‘i’s people, and by extension, the international community. Samuel Damon, an insurrectionist and traitor to Hawai‘i, stated in 1895, “If we are ever to have peace and annexation the first thing to do is to obliterate the past.” Damon also served as Trustee for the

This process, which is known as Americanization and which is a war crime, has nearly obliterated the national consciousness of the Hawaiian Kingdom in the minds of Hawai‘i’s people, and by extension, the international community. Samuel Damon, an insurrectionist and traitor to Hawai‘i, stated in 1895, “If we are ever to have peace and annexation the first thing to do is to obliterate the past.” Damon also served as Trustee for the

on business, and became interested in the native people and their government. After a candid examination of the controversies existing between their own countrymen and the Hawaiian Government, they became convinced that the latter had been unjustly accused. Sir George offered to loan the government ten thousand pounds in cash, and advised the king to send commissioners to the United States and Europe with full power to negotiate new treaties, and to obtain a

on business, and became interested in the native people and their government. After a candid examination of the controversies existing between their own countrymen and the Hawaiian Government, they became convinced that the latter had been unjustly accused. Sir George offered to loan the government ten thousand pounds in cash, and advised the king to send commissioners to the United States and Europe with full power to negotiate new treaties, and to obtain a guarantee of the independence of the kingdom.

guarantee of the independence of the kingdom. Mr. Richards also received full power of attorney for the king. Sir George left for Alaska, whence he traveled through Siberia, arriving in England in November. Messrs. Richards and Haalilio sailed July 8th, 1842, in a chartered schooner for Mazatlan, on their way to the United States*

Mr. Richards also received full power of attorney for the king. Sir George left for Alaska, whence he traveled through Siberia, arriving in England in November. Messrs. Richards and Haalilio sailed July 8th, 1842, in a chartered schooner for Mazatlan, on their way to the United States* Secretary of State, from whom they received an official letter December 19th, 1842, which recognized the independence of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and declared, “as the sense of the government of the United States, that the government of the Sandwich Islands ought to be respected; that no power ought to take possession of the islands, either as a conquest or for the purpose of the colonization; and that no power ought to seek for any undue control over the existing government, or any exclusive privileges or preferences in matters of commerce.” *

Secretary of State, from whom they received an official letter December 19th, 1842, which recognized the independence of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and declared, “as the sense of the government of the United States, that the government of the Sandwich Islands ought to be respected; that no power ought to take possession of the islands, either as a conquest or for the purpose of the colonization; and that no power ought to seek for any undue control over the existing government, or any exclusive privileges or preferences in matters of commerce.” * they had been preceded by the Sir George Simpson, and had an interview with the Earl of Aberdeen, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, on the 22d of February, 1843.

they had been preceded by the Sir George Simpson, and had an interview with the Earl of Aberdeen, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, on the 22d of February, 1843.