Mauna Kea Protectors

4

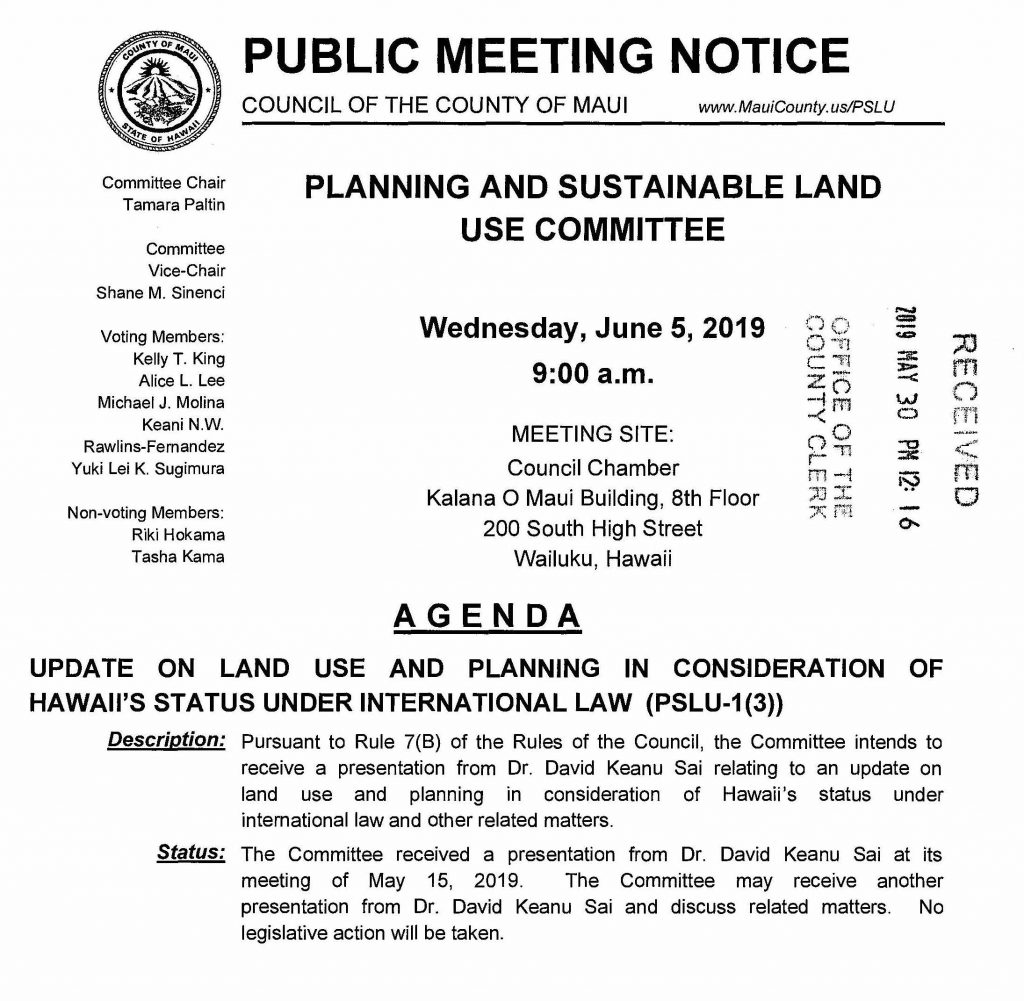

The following is one of the topics covered by Dr. Sai in his letter of July 9, 2019. Maui County Council member Tamara Paltin requested of Dr. Sai his insights into the proposed construction of the Thirty-Meter Telescope. Dr. Sai’s letter is an attachment to Council member Paltin’s letter to University of Hawai‘i President David Lassner on July 12, 2019.

Under General Lease No. S-4191 dated June 21, 1968, the Board of Land and Natural Resources of the State of Hawai‘i, as lessor, issued a 65-year lease to the University of Hawai‘i with a commencement date of January 1, 1968 and a termination date of December 31, 2033. The lease is comprised of 11,215.554 acres, more or less, being a portion of Government lands of the ahupua‘a of Ka‘ohe situated at Hamakua, Island of Hawai‘i identified under Tax May Key: 3rd/4.4.15:09.

The State of Hawai‘i claims to have acquired title under Section 5(b) of the 1959 Hawai‘i Admissions Act, Public Law 86-3 (73 Stat. 4), whereby “the United States grants to the State of Hawaii, effective upon its admission into the Union, the United States’ title to all public lands and other public property within the boundaries of the State of Hawaii, title to which is held by the United States immediately prior to its admission into the Union.” The United States derives its title from the 1898 Joint Resolution of Annexation (30 Stat. 750), which states “Whereas the Government of the Republic of Hawaii having, in due form, signified its consent, in the manner provided by its constitution…to cede and transfer to the United States the absolute fee and ownership of all public, Government, or Crown lands.”

The Republic of Hawai‘i proclaimed itself on July 3, 1894, by a convention comprised of appointed members of the Provisional Government and eighteen “elected” delegates. The Provisional Government proclaimed itself on January 17, 1893 and claimed to be the successor of the Hawaiian Kingdom. The Hawaiian Kingdom’s title derives from the 1848 Act Relating to the Lands of His Majesty The King and of the Government, whereby the ahupua‘a of Ka‘ohe is “Made over to the Chiefs and People, by our Sovereign Lord the King, and we do hereby declare those lands to be set apart as the lands of the Hawaiian Government, subject always to the rights of tenants.”

According to President Grover Cleveland, in his message to the Congress after investigating the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government that took place on January 17, 1893, the Provisional Government “was neither a government de facto nor de jure.”[1] He did not consider it a government. The President also concluded that “the provisional government owes its existence to an armed invasion by the United States.”[2] Being a creature, or creation, of the US, it could not claim to be the lawful successor of the Hawaiian Kingdom government with vested title to the ahupua‘a of Ka‘ohe. As the successor to the Provisional Government, the Republic of Hawai‘i, as it self-declared successor, could not take any better title than the Provisional Government and hence did not have title to Ka‘ohe. The U.S. Congress in the 1993 Apology Resolution noted that the Republic of Hawai‘i was “self-declared.”[3]

The United States claims to have acquired title to Ka‘ohe, by cession, from the Republic of Hawai‘i under the 1898 Joint Resolution of Annexation. International law recognizes that the “only form in which a cession can be effected is an agreement embodied in a treaty between the ceding and the acquiring State.”[4] The Joint Resolution of Annexation is not “an agreement embodied in a treaty.” It is a U.S. municipal law from the Congress merely asserting that cession took place. The situation is not unlike a neighbor holding a family meeting and claiming that they have agreed that your house is now their house.

In a debate on the Senate floor on July 4, 1898, Senator William Allen stated:

The Constitution and the statutes are territorial in their operation; that is, they can not have any binding force or operation beyond the territorial limits of the government in which they are promulgated. In other words, the Constitution and statutes can not reach across the territorial boundaries of the United States into the territorial domain of another government and affect that government or persons or property therein.[5]

The joint resolution is ipso facto null and void.[6]

In 1988, the U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Legal Counsel (“OLC”) issued a legal opinion on the lawfulness of the annexation of Hawai‘i by a joint resolution.[7] In its opinion, it cited constitutional scholar Westel Willoughby:

The constitutionality of the annexation of Hawaii, by a simple legislative act, was strenuously contested at the time both in Congress and by the press. The right to annex by treaty was denied, but it was denied that this might be done by a simple legislative act … Only by means of treaties, it was asserted, can the relations between States be governed, for a legislative act is necessarily without extraterritorial force—confined in its operation to the territory of the State by whose legislature it is enacted.[8]

The OLC concluded, “It is therefore unclear which constitutional power Congress exercised when it acquired Hawaii by joint resolution. Accordingly, it is doubtful that the acquisition of Hawaii can serve as an appropriate precedent for a congressional assertion of sovereignty over an extended territorial sea.”[9] The United States cannot produce any evidence of a conveyance of the ahupua‘a of Ka‘ohe from a grantor, vested with the title. All it can produce is a joint resolution of Congress. This is not a conveyance from a foreign State ceding territory.

Instead of providing evidence of a conveyance of territory, i.e. treaty of cession, the State of Hawai‘i Supreme Court in its October 30, 2018 majority decision In Re Conservation District Use Application for TMT, SCOT-17-0000777, quoted from a book titled Who Owns the Crown Lands of Hawai‘i written by Professor Jon Van Dyke.

The U.S. Supreme Court gave tacit recognition to the legitimacy of the annexations of Texas and Hawaiʻi by joint resolution, when it said in De Lima v. Bidwell, 182 U.S. 1, 196 (1901), that “territory thus acquired [by conquest or treaty] is acquired as absolutely as if the annexation were made, as in the case of Texas and Hawaii, by an act of Congress.” See also Texas v. White, 74 U.S. (7 Wall.) 700 (1868), stating that Texas had been properly admitted as a state in the United States.[10]

It is unclear what Professor Van Dyke meant when he stated that the U.S. Supreme Court “gave tacit recognition to the legitimacy of the annexation of Texas and Hawai‘i by joint resolution,” because tacit, by definition, is to be “understood without being openly expressed or stated.”[11] Furthermore, this statement is twice irrelevant: first, the Court as a third party to any cession of foreign territory has no standing to make such a conclusion as to what occurred between the ceding and receiving States; and, second, its opinion is a fabrication or what American jurisprudence calls a legal fiction. Legal fictions treat “as true a factual assertion that plainly was false, generally as a means to avoid changing a legal rule that required a particular factual predicate for its application.”[12]

According to Professor Smith, a “judge deploys a new legal fiction when he relies in crafting a legal rule on a factual premise that is false or inaccurate.”[13] These “new legal fictions often serve a legitimating function, and judges may preserve them—even in the face of evidence that they are false—if their abandonment would have delegitimating consequences.”[14]

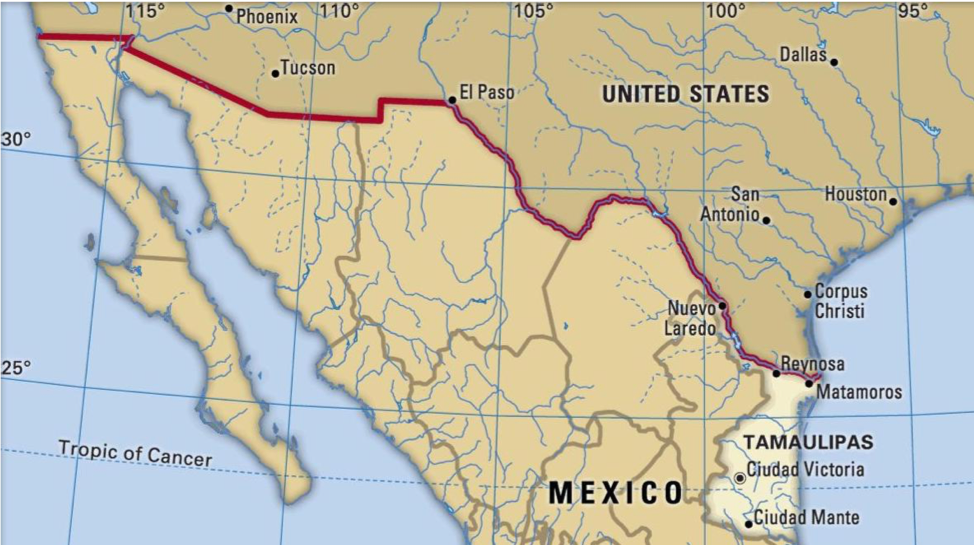

The proposition that Texas and Hawai‘i were both annexed by joint resolutions of Congress is clearly false. In the case of Texas, Congress consented to the admission of Texas as a State by joint resolution on March 1, 1845 with the following proviso, “Said State to be formed, subject to the adjustment by this government of all questions of boundary that may arise with other governments.” This condition was referring to Mexico because as Texas was comprised of insurgents who were fighting for their independence, Mexico still retained sovereignty and title to the land. In its follow up joint resolution on December 29, 1845 that admitted Texas as a State of the Union, it did state that the Congress consented “that the territory properly included within, and rightfully belonging to, the Republic of Texas.” These actions taken by the Congress is what sparked the Mexican-American War in 1846.

Congress’ statement of “rightfully belonging” is an opinion and the resolution mentions no boundaries. The transfer of title to the territory, which included the territory comprising Texas, came three years later on February 2, 1848 in a treaty of peace that ended the Mexican-American War.

Under Article V of the treaty, the new boundary line between the United States and Mexico was to be drawn. “The boundary line between the two republics shall commence in the Gulf of Mexico, three leagues from land, opposite the mouth of the Rio Grande, otherwise called Rio Bravo del Norte.”[15] Rio Brava del Norte is the southern tip of Texas. If Texas was indeed annexed in 1845 by a joint resolution with its territory intact, there was no reason for the treaty to specifically include the territory of Texas. If it were true that Texas territory was ceded in 1845, Article V of the treaty would have started the boundary line just west of the Texas city of El Paso, which is its western border, and not from the Gulf of Mexico at its southern border. The truth is that the territory of Texas was not annexed by Congress in 1845 but was ceded by Mexico in 1848. The Rio Grande river is the southern border for the State of Texas.

With regard to the so-called annexation of Hawai‘i in 1898 by Congress, there is no treaty ceding Hawaiian territory as in the case of Texas. Like the Texas resolution, Congress stated,

Whereas the Government of the Republic of Hawaii having, in due form, signified its consent, in the manner provided by its constitution to ceded absolutely and without reserve to the United States of America all rights of sovereignty of whatsoever kind in and over the Hawaiian Islands and their dependencies, and also to cede and transfer to the United States the absolute fee and ownership of all public, Government, or Crown lands, public buildings or edifices, ports, harbors, military equipment, and all other public property of every kind and description belonging to the Government of the Hawaiian Islands, together with every right and appurtenance thereunto appertaining…

The reference to consent by its constitution is specifically referring to Article 32, which states, the “President, with the approval of the Cabinet, is hereby expressly authorized and empowered to make a Treaty of Political or Commercial Union between the Republic of Hawaii and the United States of America, subject to the ratification of the Senate.”[16] There is no treaty between the so-called Republic of Hawai‘i and the United States. Furthermore, a constitutional provision is not an instrument of conveyance as a treaty would be. So without a treaty from the Hawaiian Kingdom government as the ceding State vested with the sovereignty and title to government lands, which includes the ahupua‘a of Ka‘ohe, there was no change in the ownership of the government lands.

Furthermore, Hawaiians of the day knew there was no treaty as evidenced in the Maui News newspaper published October 20, 1900. The Editor wrote,

Thomas Clark, a candidate for Territorial senator from Maui holds that it was an unconstitutional proceeding on the part of the United States to annex the Islands without a treaty, and that as a matter of fact, the Island[s] are not annexed, and cannot be, and that if the democrats come into power they will show the thing up in its true light and demonstrate that that the Islands are de facto independent at the present time.

The legal fiction that Texas and Hawai‘i were annexed by a joint resolution of the Congress is just a patently false when measured “against the results of existing empirical research.”[17] For the State of Hawai‘i Supreme Court to restate, and embrace, this falsifiable legal fiction is simply a trick that allows it to fabricate its own false and falsifiable fiction regarding the State of Hawai‘i. In its TMT decision the Court, in conflict with overwhelming evidence, stated, “[W]e reaffirm that ‘[w]hatever may be said regarding the lawfulness’ of its origins, ‘the State of Hawai‘i…is now a lawful government.’”[18] For the State of Hawai‘i to be a “lawful government” it must be vested with lawful authority absent of which it is not lawful. The State of Hawai‘i Supreme Court, being a branch of the State of Hawai‘i itself, cannot declare it “is now a lawful government” without making reference to some intervening factor that vested the State of Hawai‘i with lawful authority.

When addressing the lawful authority and sovereignty of the United States of America, the United States Supreme Court specifically referred to a particular and significant intervening factor. It stated that as “a result of the separation from Great Britain by the Colonies, acting as a unit, the powers of external sovereignty passed from the Crown not to the Colonies severally, but to the Colonies in their collective and corporate capacity as the United States of America.” The Court was referring to “the Treaty of Paris of September 3, 1783, by which Great Britain recognized the independence of the United States.”[19]

It has been erroneously assumed that the US Congress vested the State of Hawai‘i with lawful authority in the 1959 Statehood Act[20] in an exercise of the constitutional authority of Congress to admit new States into the Federal union under Article IV, section 3, clause 1. There is no provision in the US constitution for the admission of a state to the union that is on territory not owned by the US. So before the US Congress can admit a new State to the US the US must “own” the territory. According to the United States Supreme Court:

Neither the Constitution nor the laws passed in pursuance of it have any force in foreign territory unless in respect of our own citizens…, and operations of the nation in such territory must be governed by treaties, international understandings and compacts, and the principles of international law.[21]

Since the Hawaiian Islands were never annexed by the United States via treaty, Congressional acts, which are municipal laws, may only operate on the territory of the United States. The United States Supreme Court is relatively clear on this point and has stated that the “municipal laws of one nation do not extend in their operation beyond its own territory except as regards its own citizens.”[22] In another decision, the United States Supreme Court reiterated, that “our Constitution, laws and policies have no extraterritorial operation unless in respect of our own citizens.”[23]

Under international law, the United States is an occupying power in the Hawaiian Islands and as such the occupying Power is obligated, under Article 43 of the 1907 Hague Convention, IV, and Article 64 of the 1949 Geneva Convention, IV, to administer Hawaiian Kingdom laws. In his communication to the members of the Judiciary of the State of Hawai‘i of February 25, 2018, the United Nations Independent Expert, Dr. Alfred deZayas, reiterated this obligation under international law.

I have come to understand that the lawful political status of the Hawaiian Islands is that of a sovereign nation-state in continuity; but a nation-state that is under a strange form of occupation by the United States resulting from an illegal military occupation and fraudulent annexation. As such, international laws (the Hague and Geneva Conventions) require that governance and legal matters within the occupied territory of the Hawaiian Islands must be administered by the application of the laws of the occupied state (in this case, the Hawaiian Kingdom), not the domestic laws of the occupier (the United States) (Enclosure “6”).

The United States never acquired any kind of title to Ka‘ohe and, since one can only convey what one has, it could not convey what it did not have to the State of Hawai‘i under Section 5(b) of the 1959 Admissions Act. Thus the State of Hawai‘i was never lawfully vested with any title to the ahupua‘a of Ka‘ohe, and therefore its so-called general lease no. S-4191 to the University of Hawai‘i dated June 21, 1968 is defective. Under Hawaiian Kingdom law, the ahupua‘a of Ka‘ohe is government land under the management of the Ministry of the Interior and not the State of Hawai‘i Board of Land and Natural Resources. Consequently, all 10 subleases from the University of Hawai‘i that extend to December 31, 2033 are defective as well, which include:

As such, the University of Hawai‘i’s sublease to TMT International Observatory, LLC, is also defective. Therefore, the University of Hawai‘i cannot sublease what it does not have to TMT International Observatory LLC.

[1] President Cleveland’s Message to the Congress (Dec. 18, 1893), p. 453, available online at https://hawaiiankingdom.org/pdf/Cleveland’s_Message_(12.18.1893).pdf.

[2] Id., p. 454.

[3] 107 Stat. 1510.

[4] L. Oppenheim, International Law, vol. 1, second edition, 286 (1912).

[5] 31 Cong. Rec. 6635 (1898).

[6] 33 Cong. Rec. 2391 (1900).

[7] Douglas Kmiec, Department of Justice, “Legal Issues Raised by Proposed Presidential Proclamation to Extend the Territorial Sea,” 12 Opinions of the Office of Legal Counsel 238 (1988).

[8] Id., p. 252.

[9] Id.

[10] In Re Conservation District Use Application for TMT, SCOT-17-0000777, Opinion, State of Hawai‘i Supreme Court (Oct. 30, 2018), p. 46.

[11] Black’s Law, 6th ed. (1990), p. 1452.

[12] Peter J. Smith, “New Legal Fictions,” 95 The Georgetown Law Journal 1435, 1437 (2007).

[13] Id.

[14] Id., p. 1440.

[15] Treaty of Guadalup Hidalgo, 9 Stat. 926 (1848).

[16] Constitution of the Republic of Hawai‘i, Roster Legislatures of Hawaii, 1841-1918 (1918) p. 198.

[17] Smith, “New Legal Fictions,” p. 1439.

[18] In Re Conservation District Use Application for TMT, SCOT-17-0000777, Opinion, State of Hawai‘i Supreme Court (Oct. 30, 2018), p. 46.

[19] United States v. Louisiana et al., 363 U.S. 1, 68 (1960).

[20] 73 Stat. 4.

[21] United States v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp., 299 U.S. 304, 318 (1936).

[22] The Appollon, 22 U.S. (9 Wheat.) 362 (1824).

[23] United States v. Belmont, 301 U.S. 324, 332 (1936).

Aloha nui kākou,

Today David Ige reaffirmed the State of Hawaiʻi’s commitment to ensure the construction of the Thirty Meter Telescope on Maunakea beginning Monday, July 15, 2019. Ige also reaffirmed the State’s commitment to protect the interests of foreign, private corporations rather than the rights of the people of Hawaiʻi through a long, coordinated and organized mass mobilization of Hawaʻi law enforcement at the expense of Hawaiʻi tax-payers.

ʻAkahi, Kanaka Maoli have never given consent to the construction of the TMT on Maunakea. In fact, we have overwhelmingly demonstrated our opposition to the construction of the TMT in every venue; court cases, testimonies, declarations, hearings, forums, and community meetings. The most explicit examples were the series of large protests and arrests of dozens of Kiaʻi (Protectors) on Maunakea which physically halted the construction of the TMT in 2015.

ʻAlua, Kanaka Maoli reassert our rights to our national crown and government lands. The TMT Corporation has no interest or ownership in the land. The summit of Maunakea, specifically the exact location where the TMT Corporation hopes to build their telescope, are national lands of Kanaka Maoli. Indeed, the TMT Corporation has a mere sublease from the University of Hawaiʻi.

ʻAkolu, we reaffirm that Maunakea is sacred to Kanaka Maoli. The summit of Maunakea is kapu as the highest point in the Pacific. Therefore, like all humanity, we have sacred places that should be recognized and protected.

ʻAhā, we emphasize that the summit of Maunakea is a conservation district. It is environmentally sensitive and pristine. Yet the TMT Corporation plans to build a telescope that is over 180 feet tall in a place that lawfully should be afforded the highest level of environmental protection as a recognized conservation district.

ʻAlima, Kanaka Maoli will continue to assert and increase stewardship of Mauna Kea. We affirm our rights as hoaʻāina to access and manage our national lands, to practice our religion and culture and to protect these lands from further destruction and desecration.

Therefore, while the TMT Corporation and the State of Hawaiʻi continue to ignore our massive opposition and existence as a living people, Kanaka Maoli have no other choice but to engage in peaceful and nonviolent direct action.

We will forever fight the TMT, until the last aloha ʻāina. Truth and history are on our side, and our commitment and mana is only rising. We are prepared for intense and lengthy struggles but stand firm in Kapu Aloha – peace and nonviolence. We ask everyone to honor this kuleana and to conduct ourselves in PONO.

On June 10th, Rick Daysog released a Hawai‘i News Now article titled “State alleges Hawaiian scholar with a troubled past bilked distressed homeowners.” The article claims that Dr. Keanu Sai is the subject of a current criminal investigation in which allegedly “Sai’s conduct constitutes a felony and Sai’s criminal wrongdoing has been referred to the proper criminal authorities for investigation,” according to Daysog’s source OCP attorney James Evers, who wrote the excerpt in a court pleading over a year ago. The most outstanding problem with Daysog’s article is that he should have written it 14 months ago, before the case against Dr. Sai was dismissed.

In all cases of consulting, Dr. Sai always had a contract with his clients who sought his assistance. In this case, the family entered into a contract with Dr. Sai in 2015 where it clearly stated “The client has had the opportunity to investigate and verify Dr. Sai’s credentials, and agrees that Dr. Sai is qualified to perform the services in this contract.”

The contract also states that the “tasks performed under this agreement, includes but not limited to analysis, calculations, conclusions, preparation of reports, letters of correspondence and pleadings, and necessary travel time.” The agreed upon service was to provide consulting regarding the court’s lack of jurisdiction, whether criminal or civil cases, within the rules of the court. Under these contracts, Dr. Sai was admitted by the judges in seven court cases, which included both civil and criminal cases, as an expert on the subject of the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom, international law, and constitutional law.

The contract did not involve any foreclosure or mortgage issue. It included only testimony on the issue of jurisdiction. OCP attorney Evers made his false allegations against Dr. Sai in his role as a jurisdiction witness. Evers falsely represented to the Court that Dr. Sai and the family had no written contract. Dr. Sai provided Evers a copy at the beginning of the proceedings. Lawyers have a duty to correct false statements made in Court. Evers never corrected his false statement but, instead, continued to make false allegations of felonious conduct.

Dr. Sai details the case as follows, “My attorney filed a motion to dismiss, because Evers failed to even file a complaint as required by the rules. A complaint initiates a case. When this was pointed out Judge Crabtree dismissed the case. Case over!”

Back Story

The proceedings were dismissed a long time ago. Evers’s false allegations were made more than 14 months ago. It seems stale for the media to focus on it now. Hawai‘i News Now did not mention that the case was dismissed earlier this year.

State of Hawai‘i officials have spent much time manipulating the media because of his scholarly role in exposing the illegal U.S. military occupation of the Hawaiian Islands. Dr. Sai is only one of several scholars addressing this issue. In a February 25, 2018 memorandum from United Nations Independent Expert, Dr. Alfred deZayas, from Geneva, Switzerland, to members of the State of Hawai‘i judiciary, he wrote “the lawful political status of the Hawaiian Islands is that of a sovereign nation state in continuity, but a nation state that is under a strange form of occupation by the United States, resulting from an illegal military occupation and a fraudulent annexation.” Dr. Sai’s work in this matter was limited to this issue.

“the lawful political status of the Hawaiian Islands is that of a sovereign nation state in continuity, but a nation state that is under a strange form of occupation by the United States, resulting from an illegal military occupation and a fraudulent annexation”

The UN memorandum acknowledged Dr. Sai’s decades of work beginning in the 1990’s. Before Dr. Sai had a Ph.D on the isse, he had exposed the defects in land titles in Hawai‘i that were conveyed after the US invasion and illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom Government in 1893. The reason is, as Dr. Sai has simply pointed out, “there were no Hawaiian Kingdom notaries after 1893 and they are needed for the transaction.” The purpose of a notary is to validate the transfer of title. In reference to the US invasion and support of the 1893 insurgency, “if the notary was an insurgent, how do you know the person transferring the title doesn’t have a gun to his head.”

When Dr. Sai exposed this US occupation in the mid-90’s, while with a title search company “Perfect Title”, the office was raided by the White Collar Crime Unit of the Honolulu Police Department and he was arrested for theft, racketeering, and tax evasion. Matters unassociated with title reports or their effect on mortgages and title insurance. The sound bite accusation, then as now, was that he was telling elderly people not to pay their mortgages. Kau’i Sai-Dudoit, who worked as the office manager for Perfect Title, explains with a little laughter, “we were just doing title research.”

When Dr. Sai exposed this US occupation in the mid-90’s, while with a title search company “Perfect Title”, the office was raided by the White Collar Crime Unit of the Honolulu Police Department and he was arrested for theft, racketeering, and tax evasion. Matters unassociated with title reports or their effect on mortgages and title insurance.

Almost all of the charges were eventually dropped. The charge of theft was pursued. The prosecutor argued that Dr. Sai had tried to steal a house which he had never been in. The judge eventually realized that it was a “political” trial. She effectively apologized to Dr. Sai for the State’s actions at his sentencing. The minimum possible sentence of 5 years probation was imposed. It was while “on probation” that Dr. Sai began his doctoral research.

This Perfect Title matter was a manufactured charge of attempting to steal real property. Real property is “immovable.” Personal property, on the other hand, is “moveable”. Real property is not the subject of theft, only personal property is.

After sentencing, in March 2000, Dr. Sai, traveled to the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague, Netherlands, and led the legal team representing the Council of Regency of the Hawaiian Kingdom in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom. The Permanent Court of Arbitration accepted the case for dispute resolution under international law. In doing so, Permanent Court of Arbitration confirmed the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a nation State and the Council of Regency as its provisional government. Local news media in Hawai‘i has never reported on this landmark case or its international significance.

No witness, document, or legal argument has contested Dr. Sai opinions. This fact is that the Hawaiian Islands were never lawfully annexed or ceded to the United States under either US law or international law. They were simply taken. There is no treaty of annexation, and no ratified legal agreement between the two countries.

In 2008, Dr. Sai received his Ph.D. in political science specializing in international relations and public law from the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa. His doctoral research and publications focused on the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom under a prolonged and illegal occupation by the United States for over a century. Dr. Sai is a political scientist that teaches undergraduate courses in the Hawaiian Studies Department at Windward Community College. He also teaches a graduate course at the University of Hawai‘i College of Education titled “Introduction to the Hawaiian State.”

Hawai‘i’s situation, in terms of international and national law, is widely accepted and documented throughout academia. The National Education Association, the United States’ largest union of over 3 million members, published 3 articles on their website regarding the illegal occupation of Hawai‘i. Dr. Sai authored these articles.

The National Lawyers Guild, a large association of U.S. attorneys and legal workers, has acknowledged the occupation and created a Hawaiian Kingdom Subcommittee. The Subcommittee’s purpose is to provide “legal support to the movement demanding that the U.S., as the occupier, comply with international humanitarian and human rights law within Hawaiian Kingdom territory, the occupied.”

Many organizations have taken this issue very seriously and done their due diligence to come to the conclusion that the Hawaiian Kingdom is in fact an occupied nation State.

Dr. Sai continues his educational outreach. He is proving to be successful in enlightening individuals, both in Hawai‘i and around the world as to the occupation of Hawai‘i. Timing is important. It is only now, 14 months after a single unconfirmed allegation of a “referral” to an unnamed government office was made by a lawyer suing Dr. Sai, does Daysog preceded by Lind, but apparently working together, bring it up. So the public is presented with a reporter interviewing a blogger as if that is “real” news. This is the picture: One guy who doesn’t know anything is talking to another guy who doesn’t know anything but has read something.

So the public is presented with a reporter interviewing a blogger as if that is “real” news. This is the picture: One guy who doesn’t know anything is talking to another guy who doesn’t know anything but has read something.

On May 15th, the Maui County Council invited Dr. Sai to present on the status of Hawai‘i as an occupied nation State under international law. A few days prior, Ian Lind blogged regarding 1990’s Perfect Title case, as if it were “news”. Lind cited the same dismissed case that Rick Daysog recently ‘reported’ on.

Daysog’s article comes a few days after Dr. Sai presented to the Maui County Council for a second time on June 5th. Timing is important. The ‘articles’ come at a crucial time, when Dr. Sai is working with Maui County Council members. Both articles have printed unconfirmed assertions by a lawyer and have, in effect, misled their readership. The OCP initiated a legal proceeding against Dr. Sai in early 2018. It was dismissed as improperly filed in early 2019. No evidence was ever presented. It is now the middle of 2019 and Daysog and Lind are seemingly pursuing either their or another’s political agenda, as they only now raise the uncorroborated and unconfirmed “referral” to an unidentified “office”. The lack of confirmation or corroboration is astonishing. This is unserious “reporting”.

It is now the middle of 2019 and Daysog and Lind are seemingly pursuing either their or another’s political agenda, as they only now raise the uncorroborated and unconfirmed “referral” to an unidentified “office”. The lack of confirmation or corroboration is astonishing. This is unserious “reporting”.

In his follow up presentation to the Maui Council on June 5th, Dr. Sai explained a pathway for the Council to take in fixing the problem of being an unlawful government and an extension of the United States government. The legal issue for State and County governing bodies in Hawai‘i is that under the laws of occupation the occupying country is required to enforce the laws of the occupied State. The February 2018 UN memorandum explains, “international laws (the Hague and Geneva conventions) require that governance and legal matters within the occupied territory of the Hawaiian Islands must be administered by the application of the laws of the occupied state (in this case, the Hawaiian Kingdom), not the domestic laws of the occupier (the United States).”

This has presented an operational problem for State of Hawai‘i legislators and County lawmakers in Hawai‘i. The question and challenge becomes, “How to legislate without violating international laws and incurring criminal liability?” Daysog and Lind show neither an ability to, nor interest in, understanding the situation.

This question was first taken up by then-Hawai‘i County Council member Jennifer Ruggles. Ruggles was first informed at one of Dr. Sai’s presentations. She followed up by doing her due diligence and hired an attorney. In August of 2018, she refused to vote as a council member, requesting that her county attorney assure her that she would not be violating international law and incurring criminal liability on herself. Ruggles’ story has been the subject of a feature documentary called “Speaking Truth to Power.”

Dr. Sai’s second presentation to the Maui County Council informed Council members of a process that they could pursue which would bring them into compliance with international law, Hawaiian Kingdom law, and U.S. law (as the prolonged occupation of Hawai‘i also violates the U.S. constitution). Dr. Sai has dedicated much of his adult life to fixing the problems caused by the illegal US invasion, occupation, and overthrow of the legal Hawaiian Kingdom government. He has always been ready to work with State and County officials to provide a pathway that would bring them into compliance with international law. Asking for legal compliance is hardly a radical idea. It is a conservative and pragmatic approach to a complex problem caused by the US.

Dr. Sai has dedicated much of his adult life to fixing the problems caused by the illegal US invasion, occupation, and overthrow of the legal Hawaiian Kingdom government. He has always been ready to work with State and County officials to provide a pathway that would bring them into compliance with international law. Asking for legal compliance is hardly a radical idea. It is a conservative and pragmatic approach to a complex problem caused by the US.

Some media personnel such as Lind and Daysog, for example, misinform and distract the general public which needs to be informed about the legal status of the territory in which they live, and what their rights are under international law. This issue is not about Dr. Sai as a person; it is about the occupation as a fact. Information needs to be discussed in a comprehensive and responsible manner. These two individuals who wish the respect given to journalists continue to attack the messenger. Rather than understanding or focusing on the profound impact of the message itself, they do the general public a great disservice.

The issue will not go away by distraction. The crisis of Hawai‘i’s profound legal status as an occupied nation State is a truth that is now been imbedded in academia, public education, history books, doctoral dissertations, master’s theses, law journal articles, peer review articles, scholarly memorandums, international law institutions, etc. The legal status of Hawai’i will continue to become increasingly known to the general public with or without Dr. Sai.

Daysog and Lind are not the investigative reporters they claim to be. They have shown no evidence of comprehending these international law issues. If they had they would have presented these documented facts that we all have access to online and in the public records. This is what “fake news” looks like in Hawai’i. Hawai‘i News Now is either derelict in their duty to ensure accurate reporting or they are part of the misrepresentation and distraction campaign from the beginning. This doesn’t speak well for Hawai‘i News Now.

This is what “fake news” looks like in Hawai’i. Hawai‘i News Now is either derelict in their duty to ensure accurate reporting or they are part of the misrepresentation and distraction campaign from the beginning. This doesn’t speak well for Hawai‘i News Now.

Former Swiss Consul and a Professor at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa [next year will be his 50th year at UH], Dr. Niklaus Schweizer has said, “Keanu Sai is the premiere expert here” regarding this issue. Repeatedly attacking the premier expert with frivolous charges only makes journalists, institutions, and government officials look desperate in their attempt to hold onto the vestiges of a dying lie, an absurd fraud, and a stolen nation.

At the International Committee weekend retreat in the Bay Area in March 2019, the IC launched a new subcommittee, the Hawaiian Kingdom Subcommittee. Read on to learn more about the subcommittee’s work. To reach out or join the subcommittee, contact co-chairs Martha Schmidt, Keanu Sai and Steve Laudig.

There is a common misconception that the Hawaiian Islands comprise United States territory as its political subdivision, the State of Hawai‘i. The Hawaiian Islands is the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom. In Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, the Permanent Court of Arbitration recognized “that in the nineteenth century the Hawaiian Kingdom existed as an independent State recognized as such by the United States of America, the United Kingdom and various other States (Award, para. 7.4).” By 1893, the Hawaiian Kingdom maintained over 90 embassies and consulates throughout the world and entered into treaty relations with other countries to include the United States.

The lack of any US congressional constitutional authority to annex a foreign country without a treaty was noted in a 1988 memorandum by the Office of Legal Counsel, U.S. Department of Justice, which questioned whether Congress was empowered to enact a domestic law annexing the Hawaiian State in 1898. Its author, Douglas Kmiec, cited constitutional scholar Westel Willoughby who had written: “The constitutionality of the annexation of Hawaii, by a simple legislative act, was strenuously contested at the time both in Congress and by the press. The right to annex by treaty was not denied, but it was denied that this might be done by a simple legislative act. … Only by means of treaties, it was asserted, can the relations between States be governed, for a legislative act is necessarily without extraterritorial force—confined in its operation to the territory of the State by whose legislature it is enacted.” Since 1898, the United States have been imposing American municipal laws over the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom in violation of international humanitarian law.

On February 25, 2018, Dr. Alfred M. deZayas, a United Nations Independent Expert, sent a communication to State of Hawai‘i judges stating: “I have come to understand that the lawful political status of the Hawaiian Islands is that of a sovereign nation-state in continuity; but a nation-state that is under a strange form of occupation by the United States resulting from an illegal military occupation and a fraudulent annexation. As such, international laws (the Hague and Geneva Conventions) require that governance and legal matters within the occupied territory of the Hawaiian Islands must be administered by the application of the laws of the occupied state (in this case, the Hawaiian Kingdom), not the domestic laws of the occupier (the United States).”

The Hawaiian Kingdom Subcommittee provides legal support to the movement demanding that the U.S., as the occupier, comply with international humanitarian and human rights law within Hawaiian Kingdom territory, the occupied. This support includes organizing delegations and working with the United Nations, the International Committee of the Red Cross, and NGOs addressing U.S. violations of international law and the rights of Hawaiian nationals and other Protected Persons.

For a historical and legal overview of the Hawaiian Kingdom situation see: Dr. Keanu Sai’s three articles on the Hawaiian Kingdom published by the National Education Association; and, Professor Matthew Craven’s legal brief on Hawaiian Kingdom’s continuity as a State under international law cited by Judge James Crawford in his The Creation of States in International Law (2d ed.).

The National Lawyers Guild was established in 1937 as an association equal in standing to the American Bar Association.

Status of the Hawaiian Kingdom under International Law

In 2001, the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s arbitral tribunal, in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, declared “in the nineteenth century the Hawaiian Kingdom existed as an independent State recognized as such by the United States of America, the United Kingdom and various other States, including by exchanges of diplomatic or consular representatives and the conclusion of treaties (paragraph 7.4).” The terms State and Country are synonymous.

As an independent State, the Hawaiian Kingdom entered into extensive treaty relations with a variety of States establishing diplomatic relations and trade agreements. The Hawaiian Kingdom entered into three treaties with the United States: 1849 Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation; 1875 Commercial Treaty of Reciprocity; and 1883 Convention Concerning the Exchange of Money Orders. In 1893 there were only 44 independent and sovereign States, which included the Hawaiian Kingdom, as compared to 197 today.

On January 1, 1882, it joined the Universal Postal Union. Founded in 1874, the UPU was a forerunner of the United Nations as an organization of member States. Today the UPU is presently a specialized agency of the United Nations.

By 1893, the Hawaiian Kingdom maintained over ninety Legations and Consulates throughout the world. In the United States of America, the Hawaiian Kingdom manned a diplomatic post called a legation in Washington, D.C., which served in the same function as an embassy today, and consulates in the cities of New York, San Francisco, Philadelphia, San Diego, Boston, Portland, Port Townsend and Seattle. The United States manned a legation in Honolulu, and consulates in the cities of Honolulu, Hilo, Kahului and Mahukona.

“Traditional international law was based upon a rigid distinction between the state of peace and the state of war (p. 45),” says Judge Greenwood in his article “Scope of Application of Humanitarian Law” in The Handbook of the International Law of Military Occupations (2nd ed., 2008), “Countries were either in a state of peace or a state of war; there was no intermediate state (Id.).” This is also reflected by the fact that the renowned jurist of international law, Professor Lassa Oppenheim, separated his treatise on International Law into two volumes, Vol. I—Peace, and Vol. II—War and Neutrality.

On January 16, 1893, United States troops invaded the Hawaiian Kingdom without just cause, which led to a conditional surrender by the Hawaiian Kingdom’s executive monarch, Her Majesty Queen Lili‘uokalani, the following day. Her conditional surrender read:

“I, Liliuokalani, by the grace of God and under the constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Queen, do hereby solemnly protest against any and all acts done against myself and the constitutional Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom by certain persons claiming to have established a provisional government of and for this Kingdom.

That I yield to the superior force of the United States of America, whose minister plenipotentiary, His Excellency John L. Stevens, has caused United States troops to be landed at Honolulu and declared that he would support the said provisional government.

Now, to avoid any collision of armed forces and perhaps the loss of life, I do, under this protest, and impelled by said force, yield my authority until such time as the Government of the United States shall, upon the facts being presented to it, undo the action of its representatives and reinstate me in the authority which I claim as the constitutional sovereign of the Hawaiian Islands.”

In response to the Queen’s conditional surrender of her authority, President Grover Cleveland initiated an investigation on March 11, 1893, with the appointment of Special Commissioner James Blount whose duty was to “investigate and fully report to the President all the facts [he] can learn respecting the condition of affairs in the Hawaiian Islands, the causes of the revolution by which the Queen’s Government was overthrown, the sentiment of the people toward existing authority, and, in general, all that can fully enlighten the President touching the subjects of [his] mission.” After arriving in the Hawaiian Islands, he began his investigation on April 1, and by July 17, the fact-finding investigation was complete with a final report. Secretary of State Walter Gresham was receiving periodic reports from Special Commissioner Blount and was preparing a final report to the President.

On October 18, 1893, Secretary of State Gresham reported to the President, the “Provisional Government was established by the action of the American minister and the presence of the troops landed from the Boston, and its continued existence is due to the belief of the Hawaiians that if they made an effort to overthrow it, they would encounter the armed forces of the United States.” He further stated that the “Government of Hawaii surrendered its authority under a threat of war, until such time only as the Government of the United States, upon the facts being presented to it, should reinstate the constitutional sovereign, and the Provisional Government was created ‘to exist until terms of union with the United States of America have been negotiated and agreed upon (p. 462).’” Gresham then concluded, “Should not the great wrong done to a feeble but independent State by an abuse of the authority of the United States be undone by restoring the legitimate government? Anything short of that will not, I respectfully submit, satisfy the demands of justice (p. 463).”

One month later, on December 18, 1893, the President proclaimed by manifesto, in a message to the United States Congress, the circumstances for committing acts of war against the Hawaiian Kingdom that transformed a state of peace to a state of war on January 16, 1893. Black’s Law Dictionary defines a war manifesto as a “formal declaration, promulgated…by the executive authority of a state or nation, proclaiming its reasons and motives for…war.” And according to Professor Oppenheim in his seminal publication, International Law, vol. 2 (1906), a “war manifesto may…follow…the actual commencement of war through a hostile act of force (p. 104).”

Addressing the unauthorized landing of United States troops in the capital city of the Hawaiian Kingdom, President Cleveland stated, “on the 16th day of January, 1893, between four and five o’clock in the afternoon, a detachment of marines from the United States steamer Boston, with two pieces of artillery, landed at Honolulu. The men, upwards of 160 in all, were supplied with double cartridge belts filled with ammunition and with haversacks and canteens, and were accompanied by a hospital corps with stretchers and medical supplies (p. 451).”

President Cleveland ascertained that this “military demonstration upon the soil of Honolulu was of itself an act of war, unless made either with the consent of the Government of Hawaii or for the bona fide purpose of protecting the imperiled lives and property of citizens of the United States. But there is no pretense of any such consent on the part of the Government of the Queen, which at that time was undisputed and was both the de facto and the de jure government. In point of fact the existing government instead of requesting the presence of an armed force protested against it (p. 451).” He then stated, “a candid and thorough examination of the facts will force the conviction that the provisional government owes its existence to an armed invasion by the United States (p. 454).”

“War begins,” says Professor Wright in his article “Changes in the Conception of War,” American Journal of International Law, vol. 18 (1924), “when any state of the world manifests its intention to make war by some overt act, which may take the form of an act of war (p. 758).” According to Professor Hall in his book International Law (4th ed., 1895), the “date of the commencement of a war can be perfectly defined by the first act of hostility (p. 391).”

The President also determined that when “our Minister recognized the provisional government the only basis upon which it rested was the fact that the Committee of Safety had in the manner above stated declared it to exist. It was neither a government de facto nor de jure (p. 453).” He unequivocally referred to members of the so-called Provisional Government as insurgents, whereby he stated, and “if the Queen could have dealt with the insurgents alone her course would have been plain and the result unmistakable. But the United States had allied itself with her enemies, had recognized them as the true Government of Hawaii, and had put her and her adherents in the position of opposition against lawful authority. She knew that she could not withstand the power of the United States, but she believed that she might safely trust to its justice.” He then concluded that by “an act of war, committed with the participation of a diplomatic representative of the United States and without authority of Congress, the Government of a feeble but friendly and confiding people has been overthrown (p. 453).”

“Act of hostility unless it be done in the urgency of self-preservation or by way of reprisals,” according to Hall, “is in itself a full declaration of intent [to wage war] (p. 391).” According to Professor Wright in his article “When does War Exist,” American Journal of International Law, vol. 26(2) (1932), “the moment legal war begins…statutes of limitation cease to operate (p. 363).” He also states that war “in the legal sense means a period of time during which the extraordinary laws of war and neutrality have superseded the normal law of peace in the relations of states (Id.).”

Unbeknownst to the President at the time he delivered his message to the Congress, a settlement, through executive mediation, was reached between the Queen and United States Minister Albert Willis in Honolulu. The agreement of restoration, however, was never implemented. Nevertheless, President Cleveland’s manifesto was a political determination under international law of the existence of a state of war, of which there is no treaty of peace. More importantly, the President’s manifesto is paramount and serves as actual notice to all States of the conduct and course of action of the United States. These actions led to the unlawful overthrow of the government of an independent and sovereign State. When the United States commits acts of hostilities, the President, says Associate Justice Sutherland in his book Constitutional Power and World Affairs (1919), “possesses sole authority, and is charged with sole responsibility, and Congress is excluded from any direct interference (p. 75).”

According to Representative Marshall, before later became Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, in his speech in the House of Representatives in 1800, the “president is the sole organ of the nation in its external relations, and its sole representative with foreign nations. Of consequence, the demand of a foreign nation can only be made of him (Annals of Congress, vol. 10, p. 613).” Professor Wright in his book The Control of American Foreign Relations (1922), goes further and explains that foreign States “have accepted the President’s interpretation of the responsibilities [under international law] as the voice of the nation and the United States has acquiesced (p. 25).”

Despite the unprecedented prolonged nature of the illegal occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom by the United States, the Hawaiian State, as a subject of international law, is afforded all the protection that international law provides. “Belligerent occupation,” concludes Judge Crawford in his book The Creation of States in International Law (2nd ed., 2006), “does not affect the continuity of the State, even where there exists no government claiming to represent the occupied State (p. 34).” Without a treaty of peace, the laws of war and neutrality would continue to apply.

The seventeenth of January will mark 126 years of the United States’ belligerent occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom. This outcome was initiated by “acts of war” committed by U.S. forces when the U.S. diplomat ordered an invasion on January 16, 1893, which led to the unlawful overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government on January 17th.[1] President Grover Cleveland, in his manifesto to the Congress on December 18, 1893, acknowledged that a “substantial wrong has thus been done which a due regard for our national character as well as the rights of the injured people requires we should endeavor to repair.”[2]

Instead of restoring the Hawaiian government under Queen Lili‘uokalani and repairing the “rights of the injured people,” the United States embarked on a history of deception, lies, the establishment of 118 military installations, and international crimes committed against civilians within Hawaiian territory. These injustices led to the restoration of the Hawaiian government, in situ, in 1995, in similar fashion to the formation of governments in exile during World War II under the doctrine of necessity, and to the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom arbitration, which sought to address the rights of one of those “injured people,” Lance Paul Larsen, a Hawaiian subject. Mr. Larsen was subjected to an unfair trial, unlawful confinement and pillaging by the State of Hawai‘i. These are violations of the 1907 Hague Convention, IV, and the 1949 Geneva Convention, IV, which are considered war crimes.

Lance Paul Larsen v. the Hawaiian Kingdom

The dispute centered on the allegation by Mr. Larsen that the Hawaiian government was liable for “allowing the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws over [him] within the territorial jurisdiction of the Hawaiian Kingdom.” What Mr. Larsen had to overcome was whether he could proceed to hold the Hawaiian government liable for the violation of his rights without the participation of the United States who was the entity that allegedly violated his rights.

On March 3, 2000, a meeting was held in Washington, D.C., with Mr. John Crook from the U.S. State Department, Dr. Sai as Agent for the Hawaiian government, and Ms. Ninia Parks, counsel for Mr. Larsen, where the United States was formally invited to join in the arbitration. A few weeks later, the United States notified the Permanent Court of Arbitration (“PCA”) that it will not join in the proceedings but they asked permission from the Hawaiian government and Mr. Larsen if it could have access to all pleadings and records of the case. Permission was granted. For Mr. Larsen, this gave rise to the indispensable third-party rule and whether or not he could proceed against the Hawaiian government without the participation of the United States. Unlike national courts, international courts do not have subpoena powers.

The Larsen Tribunal eventually ruled that the United States was an indispensable third-party, and without its participation in the proceedings, the Tribunal could not determine what rights of Mr. Larsen were violated by the United States in order to hold the Hawaiian government accountable for the violation of those rights. The Tribunal, however, did state in its decision that the parties could pursue fact-finding through a commission of inquiry under the jurisdiction of the PCA whenever it may enter into an agreement to do so. Fact-finding is not affected by the indispensable third-party rule, which operates in similar fashion to a United States grand jury.

After the last day of the Larsen hearings were held at the PCA on December 11, 2000, the Council, was called to an urgent meeting by Dr. Jacques Bihozagara, Ambassador for the Republic of Rwanda assigned to Belgium. Ambassador Bihozagara had been attending a hearing before the International Court of Justice on December 8, 2000, (Democratic Republic of the Congo v. Belgium), where he became aware of the Hawaiian arbitration case at the PCA.

The following day, the Council, which included Dr. Sai, as Agent, and two Deputy Agents, Peter Umialiloa Sai, acting Minister of Foreign Affairs, and Mrs. Kau‘i P. Sai-Dudoit, formerly known as Kau‘i P. Goodhue, acting Minister of Finance, met with Ambassador Bihozagara in Brussels, Belgium.[3] In that meeting, Ambassador Bihozagara explained, that since he accessed the pleadings and records of the Larsen case on December 8, he had been in communication with his government. This prompted the meeting where he conveyed to Dr. Sai, as Chairman of the Council and agent in the Larsen case, that his government was prepared to bring to the attention of the United Nations General Assembly the prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom by the United States.

After careful deliberation, the Council decided that it could not, in good conscience, accept this offer. The Council felt the timing was premature because Hawai‘i’s population remained ignorant of Hawai‘i’s profound legal position due to institutionalized denationalization—Americanization by the United States. Therefore, on behalf of the Council, Dr. Sai graciously thanked Ambassador Bihozagara for his government’s offer but stated that the Council first needed to address over a century of this denationalization. After an exchange of salutations, the meeting came to an end, and the Council returned that afternoon to The Hague.

Exposure of the Continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom through the medium of Education

The decision by the Council to forego Ambassador Bihozagara’s invitation was made in line with section 495—Remedies of Injured Belligerent, United States Army FM-27-10, which states, “In the event of violation of the law of war, the injured party may legally resort to remedial action of the following types: a. Publication of the facts, with a view to influencing public opinion against the offending belligerent.”[4] Publication of the facts was the means the Council would focus its attention on to expose the prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the circumstances of the Larsen case.

“When a well packaged web of lies has been sold to the masses over generations, the truth will seem utterly preposterous, and its speaker, a raving lunatic.” -Donald James Wheal

The belligerent occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom by the United States rests squarely within the regime of the law of occupation in international humanitarian law. The application of the regime of occupation law “does not depend on a decision taken by an international authority”,[5] and “the existence of an armed conflict is an objective test and not a national ‘decision.’”[6] According to Article 42 of the 1907 Hague Convention, IV, a State’s territory is considered occupied when it is “actually placed under the authority of the hostile army.”

Article 42 has three requisite elements: (1) the presence of a foreign State’s forces; (2) the exercise of authority over the occupied territories by the foreign State or its proxy; and (3) the non-consent by the occupied State. U.S. President Grover Cleveland’s aforementioned manifesto to the Congress, which is Annexure 1 in the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom Award, and the continued U.S. presence today without a treaty of peace firmly meets all three elements of Article 42. Hawai‘i’s people, however, have become denationalized and the history of the Hawaiian Kingdom has been, for all intents and purposes, obliterated since the United States’ takeover.

The Council needed to explain to Hawai‘i’s people that before the Permanent Court of Arbitration (“PCA”) could facilitate the formation of the Larsen tribunal the PCA had to ensure that it possessed “institutional jurisdiction.”[7] This jurisdiction required that the Hawaiian Kingdom be an existing “State.” This finding authorized the Hawaiian Kingdom’s access to the PCA pursuant to Article 47 of the 1907 Hague Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes, as a non-Contracting Power to the convention.

The PCA accepted the Larsen case as a dispute between a “State” and “private entity” and, in its annual reports from 2001 to 2011, acknowledged the Hawaiian Kingdom as a non-Contracting Power under Article 47 of the 1907 Hague Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes. For Hawai‘i’s people, this acknowledgement is significant on two levels, first, the Hawaiian Kingdom had to exist as a State under international law, otherwise the PCA would not have accepted the dispute to be settled through international arbitration, and, second, the PCA explicitly recognized the Hawaiian Kingdom as a non-Contracting Power (State) to the 1907 Hague Convention, I. A non-Contracting Power is a State that is not a signatory to the Convention.

To accomplish this educational goal, it was decided by the Council that Dr. Sai enter the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa political science department and secure an M.A. degree specializing in international relations, and then a Ph.D. with focus on the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent and sovereign State that has been under a prolonged occupation. From the University of Hawai‘i political science department, Professor Neal Milner, Professor John Wilson, and Professor Katherina Hyer; from the University of Hawai‘i Hawaiian Studies department, Professor Jon Osorio; from the University of Hawai‘i William S. Richardson School of Law—Professor Aviam Soifer; and from the University of London, SOAS, Professor Matthew Craven, served as members of his doctoral committee.

The Council’s objective was to engage over a century of denationalization through the medium of academic research and publications, both peer review and law review. As a result, awareness of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s political status has grown exponentially with multiple master’s theses, doctoral dissertations, and publications being written on the subject. What the world knew, before the Larsen case was held from 1999-2001, was drastically transformed to now. This transformation was the result of academic research in spite of the continued American occupation. The “injured people” began to ask the right questions.

“If they can get you asking the wrong questions, they don’t have to worry about answers.” -Thomas Pynchon

This scholarship prompted a well-known historian in Hawai‘i, Tom Coffman, to change the subtitle of his book in 2009, which Duke University republished in 2016, from The Story of America’s Annexation of the Nation of Hawai‘i to The History of the American Occupation of Hawai‘i. Coffman explained:

I am compelled to add that the continued relevance of this book reflects a far-reaching political, moral and intellectual failure of the United States to recognize and deal with its takeover of Hawai‘i. In the book’s subtitle, the word Annexation has been replaced by the word Occupation, referring to America’s occupation of Hawai‘i. Where annexation connotes legality by mutual agreement, the act was not mutual and therefore not legal. Since by definition of international law there was no annexation, we are left with the word occupation.

In making this change, I have embraced the logical conclusion of my research into the events of 1893 to 1898 in Honolulu and Washington, D.C. I am prompted to take this step by a growing body of historical work by a new generation of Native Hawaiian scholars. Dr. Keanu Sai writes, ‘The challenge for…the fields of political science, history, and law is to distinguish between the rule of law and the politics of power.’ In the history of Hawai‘i, the might of the United States does not make it right.[8]

In 2016, Japan’s Seijo University’s Center for Glocal Studies published an article by Dennis Riches titled This is not America: The Acting Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom Goes Global with Legal Challenges to End Occupation. At the center of this article was the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom, the Council of Regency, and the commission war crimes. Riches, who is Canadian, wrote:

[The history of the Baltic States] is a close analog of Hawai‘i because the occupation by a superpower lasted over several decades through much of the same period of history. The restoration of the Baltic States illustrates that one cannot say too much time has passed, too much has changed, or a nation is gone forever once a stronger nation annexes it. The passage of time doesn’t erase sovereignty, but it does extend the time which the occupying power has to neglect its duties and commit a growing list of war crimes.

Additionally, school teachers, throughout the Hawaiian Islands, have also been made aware of the American occupation through course work at the University of Hawai‘i and they are teaching this material in the middle schools and the high schools. This exposure led the Hawai‘i State Teachers Association (“HSTA”), which represents public school teachers throughout Hawai‘i, to introduce a resolution—New Business Item 37, on July 4, 2017, at the annual assembly of the National Education Association (“NEA”) in Boston, Massachusetts. The NEA represents 3.2 million public school teachers, administrators, and faculty and administrators of universities throughout the United States. The resolution stated:

The NEA will publish an article that documents the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Monarchy in 1893, the prolonged illegal occupation of the United States in the Hawaiian Kingdom, and the harmful effects that this occupation has had on the Hawaiian people and resources of the land.

When the HSTA delegates in attendance returned to Hawai‘i, they asked Dr. Sai to write three articles for the NEA to publish: first, The Illegal Overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom Government (April 2, 2018); second, The U.S. Occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom (October 1, 2018); and, third, The Impact of the U.S. Occupation on the Hawaiian People (October 13, 2018). Awareness of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s situation has reached countless classrooms across the United States. These publications by the NEA was the Council’s crowning jewel which stemmed from the Council’s decision to address denationalization after returning home from the PCA in 2000.

Russian Government Admits Hawai‘i was Illegally Annexed

This exposure also prompted the Russian government, on October 4, 2018, to admit that Hawai‘i was illegally annexed by the United States. This acknowledgement occurred at a seminar entitled “Russian America: Hawaiian Pages 200 Years After” held at the PIR-CENTER, Institute of Contemporary International Studies, Diplomatic Academy of the Russian Foreign Ministry, in Moscow. The topic of the seminar was the restoration of Fort Elizabeth, a Russian fort built on the island of Kaua‘i in 1817.

Leading the seminar was Dr. Vladimir Orlov, director of the PIR-CENTER. Notable participants included Deputy Foreign Minister Sergej Ryabkov, Head of the Department of European Co-operation and specialist on nuclear and other disarmament negotiations, and Russian Ambassador to the United States, Anatoly Antonov. In his concluding remarks Dr. Orlov, who incidentally referred to the U.S. military installations at Barking Sands, mentioned as an aside and in a relatively low voice: “The annexation of Hawai‘i by the US was of course illegal and everyone knows it.”

United Nations Independent Expert on Hawai‘i’s Occupation

This educational exposure also prompted United Nations Independent Expert, Dr. Alfred M. deZayas, to send a communication, dated February 25, 2018, to members of the State of Hawai‘i Judiciary stating that the Hawaiian Kingdom is an occupied State and that the 1907 Hague Convention, IV, and the 1949 Geneva Convention, IV, must be complied with. In that communication, Dr. deZayas stated:

I have come to understand that the lawful political status of the Hawaiian Islands is that of a sovereign nation-state in continuity; but a nation-state that is under a strange form of occupation by the United States resulting from an illegal military occupation and a fraudulent annexation. As such, international laws (the Hague and Geneva Conventions) require that governance and legal matters within the occupied territory of the Hawaiian Islands must be administered by the application of the laws of the occupied state (in this case, the Hawaiian Kingdom), not the domestic laws of the occupier (the United States).

This UN Independent Expert clearly stated the application of “the Hague and Geneva Conventions” requires the administration of Hawaiian Kingdom law, not United States law, in Hawaiian territory. This issue was at the center of the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom arbitration case. His characterization of a “strange occupation” is not a diminishment of the law of occupation, but rather a consequence of not complying with the law of occupation. This noncompliance has created the façade of an incorporated territory of the United States called the State of Hawai‘i. The State of Hawai‘i is a de facto proxy for the United States and maintains effective control over Hawaiian territory. The War Report 2017 refers to such entities as an armed non-state actor (ANSA) “operating in another state when that support is so significant that the foreign state is deemed to have ‘overall control’ over the actions of the ANSA.”[9]

Between the years of 1893 to 1898, the Hawaiian Kingdom was occupied by an American proxy of insurgents. There is no treaty of peace between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States except for the unilateral annexation of the Hawaiian Islands by a joint resolution of Congress. Whether by proxy or not, the United States is the occupying State and “as the right of an occupant in occupied territory is merely a right of administration, he may [not] annex it, while the war continues.”[10] The ICRC Commentary on Article 47 also emphasize, “It will be well to note that the reference to annexation in this Article cannot be considered as implying recognition of this manner of acquiring sovereignty.”[11]

The “Occupying Power cannot…annex the occupied territory, even if it occupies the whole of the territory concerned. A decision on that point can only be reached in a peace treaty. This is a universally-recognized rule and is endorsed by jurists and confirmed by numerous rulings of international and national courts.”[12] Therefore, according to the ICRC, “an Occupying Power continues to be bound to apply the Convention as a whole even when, in disregard of the rules of international law, it claims to have annexed all or part of an occupied territory.”[13] In other words, since there is no treaty of peace between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States, there was no annexation.

To understand what the UN Independent Expert called a “fraudulent annexation,” attention is drawn to the floor of the Senate on July 4, 1898, where U.S. Senator William Allen of Nebraska stated:

“The Constitution and the statutes are territorial in their operation; that is, they can not have any binding force or operation beyond the territorial limits of the government in which they are promulgated. In other words, the Constitution and statutes can not reach across the territorial boundaries of the United States into the territorial domain of another government and affect that government or persons or property therein.”[14]

Two years later, on February 28, 1900, during a debate on senate bill no. 222 that proposed the establishment of a U.S. government to be called the Territory of Hawai‘i, Senator Allen reiterated, “I utterly repudiate the power of Congress to annex the Hawaiian Islands by a joint resolution such as passed the Senate. It is ipso facto null and void.”[15] In response, Senator John Spooner of Wisconsin, a constitutional lawyer, dismissively remarked, “that is a political question, not subject to review by the courts.”[16] Senator Spooner explained, “The Hawaiian Islands were annexed to the United States by a joint resolution passed by Congress. I reassert…that that was a political question and it will never be reviewed by the Supreme Court or any other judicial tribunal.”[17]

Senator Spooner never argued that congressional laws have authority beyond United States territory. Instead, he said this issue would never see the light of day because United States courts would not review it due to the political question doctrine. What Senator Spooner meant was no matter how illegal the annexation was, the American courts will have to accept it because Congress did it. For an explanation of the evolution of the political question doctrine regarding Hawai‘i go to this link. This exchange between the two Senators is troubling, but it acknowledges the limitation of congressional laws and the political means by which to conceal an internationally wrongful act. The Territory of Hawai‘i is the predecessor of the State of Hawai‘i.

It would take another ninety years before the U.S. Department of Justice addressed this issue. In a 1988 legal opinion, the Office of Legal Counsel examined the purported annexation of the Hawaiian Islands by a congressional joint resolution. Douglas Kmiec, Acting Assistant Attorney General, authored this opinion for Abraham D. Sofaer, legal advisor to the U.S. Department of State. After covering the limitation of congressional authority, which, in effect, confirmed the statements made by Senator Allen, Assistant Attorney General Kmiec concluded:

Notwithstanding these constitutional objections, Congress approved the joint resolution and President McKinley signed the measure in 1898. Nevertheless, whether this action demonstrates the constitutional power of Congress to acquire territory is certainly questionable. … It is therefore unclear which constitutional power Congress exercised when it acquired Hawaii by joint resolution. Accordingly, it is doubtful that the acquisition of Hawaii can serve as an appropriate precedent for a congressional assertion of sovereignty over an extended territorial sea.[18]

War Crimes—Violations of the Hague and Geneva Conventions

All this education and exposure has motivated an elected official for the State of Hawai‘i, while still in office, to take steps to conform to the 1907 Hague Convention, IV, and the 1949 Geneva Convention, IV. Her story was published by the British news outlet The Guardian, titled Hawai‘i politician stops voting, claiming islands are ‘occupied sovereign country.’ Other public officials of the State of Hawai‘i have also become aware of the American occupation and are taking steps to conform with international humanitarian law. They have reached out to Dr. Sai for consultation.

Moreover, on October 11, 2018, the Federal Bureau of Investigation was sent a letter, from Jennifer Ruggles, the aforementioned State of Hawai‘i public official, reporting war crimes committed by the Queen’s Hospital, in violation of 18 U.S.C. §2441 and §1091, and war crimes committed by thirty-two Circuit Judges of the State of Hawai‘i, in violation of 18 U.S.C. §2441.[19] Thereafter, Ms. Ruggles reported additional war crimes of pillaging committed by State of Hawai‘i tax collectors, in violation of §2441,[20] the war crime of unlawful appropriation of property by the President of the United States and the Internal Revenue Service, in violation of §2441,[21] and the war crime of destruction of property by the State of Hawai‘i on the summit of Mauna Kea, in violation of §2441.[22]

Naboth’s Vineyard

Within nearly two decades the Council has effectively changed the discourse of Hawai‘i politics and history from the façade of American colonization and the formation of the State of Hawai‘i to the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a sovereign and independent State that has and continues to be under an illegal and prolonged occupation by the United States.

As we are entering over a century of non-compliance with the law of occupation and the commission of war crimes, accountability for these war crimes is just over the horizon. In her last chapter titled “Hawaiian Autonomy” of her 1898 autobiography, Hawai‘i’s Story by Hawai‘i’s Queen, Queen Lili‘uokalani warned:

Oh, honest Americans, as Christians, hear me for my down trodden people! Their form of government is as dear to them as yours is precious to you. Quite as warmly as you love your country, so they love theirs. With all your goodly possessions, covering a territory so immense that there yet remain parts unexplored, possessing islands that, although near at hand, had to be neutral ground in time of war, do not covet the little vineyard of Naboth’s so far from your shores, lest the punishment of Ahab fall upon you, if not in your day in that of your children, for “for be not deceived, God is not mocked.”

[1] Award (Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom), Annexure 1, President Cleveland’s message to the Senate and House of Representatives dated 18 December 1893, 119 ILR (2001), 566, 608.

[2] Id.

[3] David Keanu Sai, A Slippery Path towards Hawaiian Indigeneity, 10 J. L. & Soc. Challenges 69, 130-131 (2008).

[4] “United States Basic Field Manual F.M. 27-10 (Rules of Land Warfare), though not a source of law like a statute, prerogative order or decision of a court, is a very authoritative publication.” Trial of Sergeant-Major Shigeru Ohashi and Six Others, 5 Law Reports of Trials of Law Criminals (United Nations War Crime Commission) 27 (1949).

[5] C. Ryngaert and R. Fransen, “EU extraterritorial obligations with respect to trade with occupied territories: Reflections after the case of Front Polisario before EU courts,” [2018] 2(1): 7. Europe and the World: A law review [20], p. 8. (online at https://www.scienceopen.com/document_file/e5cc1ac6-41ee-40de-bbe9-25c9df97ab1e/ScienceOpen/EWLR-2-7.pdf).

[6] Stuart Casey-Maslen (ed.), The War Report 2012 ix (2013).

[7] United Nations, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: Dispute Settlement (United Nations New York and Geneva, 2003), at 15.

[8] Tom Coffman, Nation Within: The History of the American Occupation of Hawai‘i xvi (2016).

[9] The War Report 2017, 22.

[10] Oppenheim, International Law, vol. II, 6th ed., 237 (1921).