Dr. Keanu Sai was invited to do a podcast interview by Professor Pascal Lottaz on the subject of the American occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom, a Neutral State. Professor Lottaz is an Assistant Professor for Neutrality Studies at the Waseda Institute for Advanced Study in Tokyo. He is a also a researcher at Neutrality Studies, where its YouTube channel, which airs their podcasts, has 153,000 subscribers worldwide.

Category Archives: Education

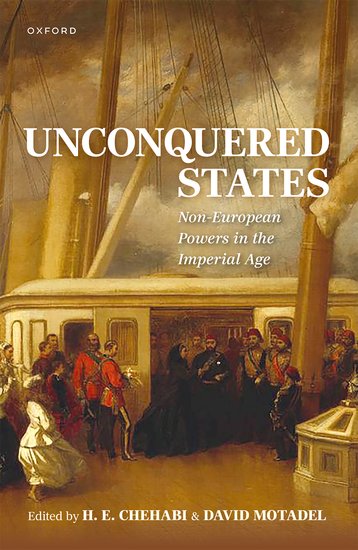

Oxford University Press will make it Official—Hawai‘i is the Longest Occupation in Modern History

With Oxford University Press (OUP) upcoming release, on December 30, 2024, of Unconquered States: Non-European Powers in the Imperial Age with a chapter by Dr. Keanu Sai on the Hawaiian Kingdom and its continued existence as a State despite having been under a prolonged American occupation since 1893, it will make it official that Hawai‘i is the longest occupation in modern history. Previously, it was thought that the longest occupation was Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and East Jerusalem that began in 1967.

The reach of OUP is worldwide. In all its publications it states “Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford, Auckland, Cape Town, Dar es Salaam, Hong Kong, Karachi, Kuala Lumpur, Madrid, Melbourne, Mexico City, Nairobi, New Delhi, Shanghai, Taipei, and Toronto. With offices in Argentina, Austria, Brazil, Chile, Czech Republic, France, Greece, Guatemala, Hungary, Italy, Japan, Poland, Portugal, Singapore, South Korea, Switzerland, Thailand, Turkey, Ukraine, and Vietnam.”

Dr. Sai’s chapter has effectively pierced the false narrative that has plagued Hawai‘i’s population and the world that Hawai‘i is an American state, rather than an occupied State. The Hawaiian Kingdom’s continued existence as an occupied State is not a legal argument but rather a legal fact with consequences under international law. Dr. Sai concludes his chapter with:

Despite over a century of revisionist history, “the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a sovereign State is grounded in the very same principles that the United States and every other State have relied on for their own legal existence.” The Hawaiian Kingdom is a magnificent story of perseverance and continuity.

With the world knowing about the American occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom it will assist in facilitating compliance by the Hawai‘i Army National Guard with the law of occupation so that the American occupation will eventually come to an end by a treaty of peace.

Oxford University Press to release “Unconquered States: Non-European Powers in the Imperial Age” with a chapter on the Hawaiian Kingdom

On December 30, 2024, Oxford University Press will be releasing a book titled Unconquered States: Non-European Powers in the Imperial Age. The editors of the book, Professor H. E. Chehabi from Boston University and Professor David Motadel from the London School of Economics and Political Science, invited 23 scholars from around the world to contribute their scholarship. Dr. Keanu Sai is the author of chapter 21—Hawai‘i’s Sovereignty and Survival in the Age of Empire.

Here are the reviews:

“This is an ingenious collection, a book on international history in the 19th and 20th centuries that really does, for once, “fill a gap.” By countering our simple assumption that the West’s imperial and colonial drives swallowed up all of Africa and Asia in the post-1850 period, Chehabi and Motadel’s fine collection of case-studies of nations that managed to stay free—from Abyssinia to Siam, Japan to Persia—gives us a more rounded and complex view of the international Great-Power scene in those decades. This is really fine revisionist history.”—Paul Kennedy, Yale University

“This is an excellent collection of scholars writing on an important set of states, which deserve to be considered together.”—Kenneth Pomeranz, University of Chicago

“Carefully curated and with an excellent introduction that provides an analytical frame, this book offers a global history of “unconquered” countries in the imperial age that is original in its perspective and composition.”—Sebastian Conrad, Free University of Berlin

“The book offers an insightful comparative analysis of political forms and relationships in non-European countries from the 18th to the early 20th centuries. The “non-conquered states” of Asia and Africa are show as sometimes resisting and but often accommodating in innovative ways European political forms and military and diplomatic techniques. The particular appeal of the essays lies in their effort to bring to the surface and critically assess the indigenous histories and struggles that enabled these political formations, each in their own way, to respond to the challenges of modernization. This is global history at its kaleidoscopic best.”—Martti Koskenniemi, University of Helsinki

Oxford University Press is the gold standard for academic publishing in the world and to have the untold story of the Hawaiian Kingdom and its continued existence under an American occupation is a monumental feat for the Council of Regency’s strategic plan under Phase II—exposure of Hawaiian Statehood. Dr. Sai is not only a Hawaiian scholar and political scientist, but he is also Chairman of the acting Council of Regency.

When the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom was restored in 1997, as an acting Council of Regency under Hawaiian constitutional law and the legal doctrine of necessity, it approached the prolonged American occupation with a strategic plan that entailed three phases:

Phase I: Verification of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an Independent State and subject of international law where a reputable international body must verify the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State.

Phase II: Exposure of Hawaiian Statehood within the framework of international law and the law of occupation as it affects the realm of politics and economics at both the international and domestic levels. Phase II will focus on individual accountability and compliance to the law of occupation.

Phase III: Restoration of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State and a subject of international law, which is when the occupation will come to an end by a treaty of peace.

On November 8, 1999, international arbitration proceedings were initiated at the Permanent Court of Arbitration, in The Hague, Netherlands, in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, PCA Case no. 1999-01. At its website, the PCA described the dispute as:

Lance Paul Larsen, a resident of Hawaii, brought a claim against the Hawaiian Kingdom by its Council of Regency (“Hawaiian Kingdom”) on the grounds that the Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom is in continual violation of: (a) its 1849 Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation with the United States of America, as well as the principles of international law laid down in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 1969 and (b) the principles of international comity, for allowing the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws over the claimant’s person within the territorial jurisdiction of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

Before an arbitral tribunal could be established by the PCA, it had to determine that the dispute was international, which meant the Hawaiian Kingdom had to be an existing State under customary international law. Once the PCA recognized the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State and the Council of Regency as its government, it then had to determine whether the Hawaiian Kingdom was a Contracting State or Non-Contracting State to the 1907 Hague Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes (PCA Convention) that established the PCA.

The reasoning for this determination was that Contracting States, which includes the United States, did not pay for the use of the facilities because they contributed yearly dues to maintain the PCA. Non-Contracting States had to pay for the use of the facilities. The PCA recognized the Hawaiian Kingdom as a Non-Contracting State under Article 47 of the PCA Convention. The PCA established the arbitral tribunal on June 9, 2000. To understand this case you can go to pages 24-27 of the ebook Royal Commission of Inquiry: Investigating War Crimes and Human Rights Violations Committed in the Hawaiian Kingdom.

The PCA’s recognition of the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1999 satisfied Phase I. Since then, Phase II was initiated and continued when Dr. Sai entered the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa in 2001 to acquire an M.A. degree and a Ph.D. degree in political science specializing in international relations and law. According to Dr. Sai:

The Council of Regency needed to institutionalize, and not politicize, the legal and political history of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State under international law and its continued existence today. This would be done by academic research and publications that will normalize the fact of the American occupation. From this premise, we could move into compliance to the law of occupation where the occupation will eventually come to an end by a treaty of peace. This was the most viable approach to a revisionist history that has been perpetrated for over a century.

Awaiaulu—Video Story of Hawaiian Independence

National Holiday – Lā Kūʻokoʻa (Independence Day)

November 28th is the most important national holiday in the Hawaiian Kingdom. It is the day Great Britain and France formally recognized the Hawaiian Islands as an “independent state” in 1843, and has since been celebrated as “Independence Day,” which in the Hawaiian language is “La Ku‘oko‘a.” Here follows the story of this momentous event from the Hawaiian Kingdom Board of Education history textbook titled “A Brief History of the Hawaiian People” published in 1891.

**************************************

The First Embassy to Foreign Powers—In February, 1842, Sir George Simpson and Dr. McLaughlin, governors in the service of the Hudson Bay Company, arrived at Honolulu on

business, and became interested in the native people and their government. After a candid examination of the controversies existing between their own countrymen and the Hawaiian Government, they became convinced that the latter had been unjustly accused. Sir George offered to loan the government ten thousand pounds in cash, and advised the king to send commissioners to the United States and Europe with full power to negotiate new treaties, and to obtain a guarantee of the independence of the kingdom.

Accordingly Sir George Simpson, Haalilio, the king’s secretary, and Mr. Richards were appointed joint ministers-plenipotentiary to the three powers on the 8th of April, 1842.

Mr. Richards also received full power of attorney for the king. Sir George left for Alaska, whence he traveled through Siberia, arriving in England in November. Messrs. Richards and Haalilio sailed July 8th, 1842, in a chartered schooner for Mazatlan, on their way to the United States*

*Their business was kept a profound secret at the time.

Proceedings of the British Consul—As soon as these facts became known, Mr. Charlton followed the embassy in order to defeat its object. He left suddenly on September 26th, 1842, for London via Mexico, sending back a threatening letter to the king, in which he informed him that he had appointed Mr. Alexander Simpson as acting-consul of Great Britain. As this individual, who was a relative of Sir George, was an avowed advocate of the annexation of the islands to Great Britain, and had insulted and threatened the governor of Oahu, the king declined to recognize him as British consul. Meanwhile Mr. Charlton laid his grievances before Lord George Paulet commanding the British frigate “Carysfort,” at Mazatlan, Mexico. Mr. Simpson also sent dispatches to the coast in November, representing that the property and persons of his countrymen were in danger, which introduced Rear-Admiral Thomas to order the “Carysfort” to Honolulu to inquire into the matter.

Recognition by the United States—Messres. Richards and Haalilio arrived in Washington early in December, and had several interviews with Daniel Webster, the Secretary of State, from whom they received an official letter December 19th, 1842, which recognized the independence of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and declared, “as the sense of the government of the United States, that the government of the Sandwich Islands ought to be respected; that no power ought to take possession of the islands, either as a conquest or for the purpose of the colonization; and that no power ought to seek for any undue control over the existing government, or any exclusive privileges or preferences in matters of commerce.” *

*The same sentiments were expressed in President Tyler’s message to Congress of December 30th, and in the Report of the Committee on Foreign Relations, written by John Quincy Adams.

Success of the Embassy in Europe—The king’s envoys proceeded to London, where they had been preceded by the Sir George Simpson, and had an interview with the Earl of Aberdeen, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, on the 22d of February, 1843.

Lord Aberdeen at first declined to receive them as ministers from an independent state, or to negotiate a treaty, alleging that the king did not govern, but that he was “exclusively under the influence of Americans to the detriment of British interests,” and would not admit that the government of the United States had yet fully recognized the independence of the islands.

Sir George and Mr. Richards did not, however, lose heart, but went on to Brussels March 8th, by a previous arrangement made with Mr. Brinsmade. While there, they had an interview with Leopold I., king of the Belgians, who received them with great courtesy, and promised to use his influence to obtain the recognition of Hawaiian independence. This influence was great, both from his eminent personal qualities and from his close relationship to the royal families of England and France.

Encouraged by this pledge, the envoys proceeded to Paris, where, on the 17th, M. Guizot, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, received them in the kindest manner, and at once engaged, in behalf of France, to recognize the independence of the islands. He made the same statement to Lord Cowley, the British ambassador, on the 19th, and thus cleared the way for the embassy in England.

They immediately returned to London, where Sir George had a long interview with Lord Aberdeen on the 25th, in which he explained the actual state of affairs at the islands, and received an assurance that Mr. Charlton would be removed. On the 1st of April, 1843, the Earl of Aberdeen formally replied to the king’s commissioners, declaring that “Her Majesty’s Government are willing and have determined to recognize the independence of the Sandwich Islands under their present sovereign,” but insisting on the perfect equality of all foreigners in the islands before the law, and adding that grave complaints had been received from British subjects of undue rigor exercised toward them, and improper partiality toward others in the administration of justice. Sir George Simpson left for Canada April 3d, 1843.

Recognition of the Independence of the Islands—Lord Aberdeen, on the 13th of June, assured the Hawaiian envoys that “Her Majesty’s government had no intention to retain possession of the Sandwich Islands,” and a similar declaration was made to the governments of France and the United States.

At length, on the 28th of November, 1843, the two governments of France and England united in a joint declaration to the effect that “Her Majesty, the queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and His Majesty, the king of the French, taking into consideration the existence in the Sandwich Islands of a government capable of providing for the regularity of its relations with foreign nations have thought it right to engage reciprocally to consider the Sandwich Islands as an independent state, and never to take possession, either directly or under the title of a protectorate, or under any other form, of any part of the territory of which they are composed…”

This was the final act by which the Hawaiian Kingdom was admitted within the pale of civilized nations. Finding that nothing more could be accomplished for the present in Paris, Messrs. Richards and Haalilio returned to the United States in the spring of 1844. On the 6th of July they received a dispatch from Mr. J.C. Calhoun, the Secretary of State, informing them that the President regarded the statement of Mr. Webster and the appointment of a commissioner “as a full recognition on the part of the United States of the independence of the Hawaiian Government.”

The Hawaiian Finger Trap and the State of Hawai‘i

The Chinese finger trap, which is a woven cylinder, is when a person puts their index fingers in both ends of the cylinder and try to pull their fingers out, the weave of the cylinder tightens around the fingers. The trap is in the way in which the material is woven. And so we have the Hawaiian finger trap that State of Hawai‘i Attorney General Anne Lopez finds herself in when Senator Cross Makani Crabbe wrote a formal letter requesting for a legal opinion about the State of Hawai‘i and its lawful status within the Hawaiian Kingdom.

The weave of the Hawaiian finger trap is made of years of historical facts interwoven with international law since the Hawaiian Kingdom became a sovereign and independent State on November 28, 1843, and, thereby, becoming a member of the Family of Nations. The United States followed by recognizing Hawaiian independence on July 6, 1844. By 1893, the Hawaiian Kingdom had twenty-seven treaties with other countries, four of these treaties is with the United States.

The Hawaiian Kingdom maintained diplomatic representatives and consulates accredited to other countries. Hawaiian Legations were established in Washington, D.C., London, Paris, Lima, Valparaiso, and Tokyo, while diplomatic representatives and consulates accredited to the Hawaiian Kingdom were from the United States, Portugal, Great Britain, France, and Japan. There were two Hawaiian consulates in Mexico; one in Guatemala; two in Peru; one in Chile; one in Uruguay; thirty-three in Great Britain and her colonies; five in France and her colonies; five in Germany; one in Austria; ten in Spain and her colonies; five in Portugal and her colonies; three in Italy; two in the Netherlands; four in Belgium; four in Sweden and Norway; one in Denmark; one in Japan; and eight in the United States. Foreign Consulates in the Hawaiian Kingdom were from the United States, Italy, Chile, Germany, Sweden and Norway, Denmark, Peru, Belgium, the Netherlands, Spain, Austria and Hungary, Russia, Great Britain, Mexico, Japan, and China.

Unlike other non-European States, the Hawaiian Kingdom, as a recognized neutral State, enjoyed equal treaties with European powers, including the United States, and full independence of its laws over its territory. In his speech at the opening of the 1855 Hawaiian Legislature, King Kamehameha IV, reported, “It is gratifying to me, on commencing my reign, to be able to inform you, that my relations with all the great Powers, between whom and myself exist treaties of amity, are of the most satisfactory nature. I have received from all of them, assurances that leave no room to doubt that my rights and sovereignty will be respected.”

In its 2001 arbitral award in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, the Tribunal at the Permanent Court of Arbitration (“PCA”) acknowledged this when it stated, “in the nineteenth century the Hawaiian Kingdom existed as an independent State recognized as such by the United States of America, the United Kingdom and various other States, including by exchanges of diplomatic or consular representatives and the conclusion of treaties.”

Independent States are protected by international law, which is why States are the benefactors of international law. Unlike laws within countries like the United States where the source of law is a legislature, on the international plane there is no legislative body that enacts international law. Instead, the sources of international law are customary law, treaties, principles of law, judicial decisions, and scholarly articles written by experts in international law. A common misunderstanding is that the United Nations General Assembly creates international laws. It does not. It only enacts resolutions or position statements that may include international law.

Under international law, there is a presumption that the State continues to exist even though its government was militarily overthrown. Because there is a presumption, not an assumption, that the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist under international law despite the United States overthrow of the Hawaiian government, the Attorney General would have to provide rebuttable evidence that there is no application of the principle of presumption because the Hawaiian Kingdom was extinguished under international law by a treaty of cession where the Hawaiian Kingdom ceded its sovereignty and territory to the United States. There is no such treaty except for American laws being imposed in the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Because the Hawaiian Kingdom exists, the State of Hawai‘i cannot lawfully exist within Hawaiian territory. The Hawaiian finger trap.

So the question the Attorney General has to answer is in light of the two legal opinions that conclude the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist under international law, is the State of Hawai‘i within the territory of the United States or is it within the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Like the presumption of innocence, the accused does not have to prove their innocence, rather the prosecution must prove with evidence beyond all reasonable doubt that the person is not innocent. What also sets the foundation is that because Professor Craven and Professor Lenzerini are scholars in international law, their legal opinions that Senator Crabbe included in his letter to the Attorney General are a part of international law.

The premise is that the State of Hawai‘i exists within the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom until she can provide evidence beyond all reasonable doubt, a treaty, that the State of Hawai‘i is within the United States. Her silence answers the question that the State of Hawai‘i is in the Hawaiian Kingdom. Her legal opinion will say the same thing.

Her silence actually works against the State of Hawai‘i because under international law there is the principle of acquiescence. According to Professor Antunes, acquiescence “concerns a consent tacitly conveyed by a State, unilaterally, through silence or inaction, in circumstances such that a response expressing disagreement or objection in relation to the conduct of another State would be called for.” Silence conveys consent. Qui tacet consentire videtur si loqui debuisset ac potuisset.

Dr. Keanu Sai does a Second Interview on Keep It Aloha Podcast

Exposing the Truth—the American Dismantling of Universal Health Care for Aboriginal Hawaiian subjects

Under Hawaiian Kingdom law, the term for Native Hawaiians today is aboriginal Hawaiian, irrespective of blood quantum. American law created a blood quantum for aboriginal Hawaiians in order to have access to a 99-year lease of land from the Hawaiian Homes Commission. Hawaiian law has no blood quantum to exercise their vested rights under the law.

Aboriginal is defined as a people who first arrived in a particular region through migration. Aboriginal Hawaiians were the first people to arrive in the Hawaiian Islands from central Polynesia. In her 1884 will that established the Kamehameha Schools, Bernice Pauahi Bishop wrote:

I direct my trustees to invest the remainder of my estate in such manner as they may think best…to devote a portion of each years income to the support and education of orphans, and others in indigent circumstances, giving the preference to Hawaiians of pure or part aboriginal blood.

Hawaiian is the short term for the nationality called Hawaiian subjects. Just as British is the short term for British subjects, which is the nationality of Great Britain. According to the 1890 census, the total population of the Hawaiian citizenry was at 48,107, with 40,622 being aboriginal Hawaiians and 7,495 being non-aboriginal.

Aboriginal Hawaiians are now beginning to see the devastating effects of the American occupation on their vested legal rights. The cause of the denial of these legal rights, under Hawaiian Kingdom law, is the unlawful imposition of American laws over the entire territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Since 1919, usurpation of sovereignty, which is the imposition of the laws of the Occupying State over the territory of the Occupied State, is a war crime. One of the legal rights of aboriginal Hawaiians is their right to free health care at Queen’s Hospital.

When the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom was restored, through an acting Council of Regency in 1997, it knew it had to raise awareness of the circumstances of the American occupation and its devastating effects since the unlawful overthrow of the Hawaiian government by United States troops on January 17, 1893. After the Permanent Court of Arbitration recognized the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State under international law, despite the unlawful overthrow of its government, and the Council of Regency as the restored government, its primary focus in exposing Hawaiian Statehood was to restore the national consciousness of the Hawaiian Kingdom in the minds of its people. This was the Hawaiian citizenry.

As part of restoring Hawaiian national consciousness, education, research, classroom instruction, and community outreach was the key to piercing through the veil of over a century of lies. As Dresden James wrote, “When a well-packaged web of lies has been sold gradually to the masses over generations, the truth will seem utterly preposterous and its speaker a raving lunatic.”

On July 31, 1901, an article was published in The Pacific Commercial Advertiser in Honolulu. It is a window into a time of colliding legal systems and the Queen’s Hospital would soon become the first Hawaiian health institution to fall victim to the unlawful imposition of American laws. The Advertiser reported:

The Queen’s Hospital was founded in 1859 by their Majesties Kamehameha IV and his consort Emma Kaleleonalani. The hospital is organized as a corporation and by the terms of its charter the board of trustees is composed of ten members elected by the society and ten members nominated by the Government, of which the President of the Republic (now Governor of the Territory) shall be the presiding officer. The charter also provides for the “establishing and putting in operation a permanent hospital in Honolulu, with a dispensary and all necessary furniture and appurtenances for the reception, accommodation and treatment of indigent sick and disabled Hawaiians, as well as such foreigners and other who may choose to avail themselves of the same.”

Under this construction all native Hawaiians have been cared for without charge, while for others a charge has been made of from $1 to $3 per day. The bill making the appropriation for the hospital by the Government provides that no distinction shall be made as to race; and the Queen’s Hospital trustees are evidently up against a serious proposition.

Queen’s Hospital was established as the national hospital for the Hawaiian Kingdom and that health care services for Hawaiian subjects of aboriginal blood was at no charge. The Hawaiian Head of State would serve as the ex officio President of the Board together with twenty trustees, ten of whom were from the Hawaiian government.

Since the hospital’s establishment in 1859, the legislature of the Hawaiian Kingdom subsidized the hospital along with monies from the Queen Emma Trust. With the unlawful imposition of the 1900 Organic Act that formed the Territory of Hawai‘i, American law did not allow public monies to be used for the benefit of a particular race. 1909 was the last year Queen’s Hospital received public funding and it was also the same year that the charter was unlawfully amended to replace the Hawaiian Head of State with an elected president from the private sector and reduced the number of trustees from twenty to seven, which did not include government officers.

These changes to a Hawaiian quasi-public institution is a direct violation of the laws of occupation, whereby the United States was and continues to be obligated to administer the laws of the occupied State—the Hawaiian Kingdom. This requirement comes under Article 43 of the 1907 Hague Regulations, and Article 64 of the Fourth Geneva Convention.

Article 55 of the 1907 Hague Regulations provides, “[t]he occupying State shall be regarded only as administrator and usufructuary of public buildings, real estate, forests, and agricultural estates belonging to the [occupied] State, and situated in the occupied country. It must safeguard the capital of these properties, and administer them in accordance with the rules of usufruct.” The term “usufruct” is to administer the property or institution of another without impairing or damaging it.

Despite these unlawful changes, aboriginal Hawaiian subjects, whether pure or part, are to receive health care at Queen’s Hospital free of charge. This did not change, but through denationalization there was a destruction of Hawaiian national consciousness that fostered the web of lies that Hawai‘i was a part of the United States, that aboriginal Hawaiians were American citizens, and there was never free healthcare at Queen’s Hospital.

Aboriginal Hawaiian subjects are protected persons as defined under international law, and as such, the prevention of health care by Queen’s Hospital constitutes war crimes. Furthermore, there is a direct nexus of deaths of aboriginal Hawaiians as “the single racial group with the highest health risk in the State of Hawai‘i [that] stems from…late or lack of access to health care” to the crime of genocide.

Once the State of Hawai‘i is transformed into a military government, according to the international law of occupation, it must immediately begin to administer the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom. The vested right of aboriginal Hawaiians to free healthcare is a law of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Included with Hawaiian Kingdom laws, as they were before the American occupation began, are the provisional laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

In 2014, the Council of Regency proclaimed these provisional laws to be all Federal, State of Hawai‘i, and County Ordinances that “do not run contrary to the express, reason and spirit of the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom.” In order to determine which laws are consistent with Hawaiian Kingdom law, Dr. Keanu Sai, as acting Minister of the Interior drafted a memorandum that was made public on August 1, 2023. A particular Federal law that is inconsistent with Hawaiian Kingdom law is the IRS tax code.

Major General Hara and Brigadier General Logan Denies 714,847 Native Hawaiians of Their Legal Right to Free Healthcare and Land under Hawaiian Law

After United States troops invaded and overthrew the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom on January 17, 1893, international law, at the time, required the United States, as the occupant, to maintain the status quo of the occupied State until a treaty of peace was agreed upon between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States. To maintain that status quo of the Hawaiian Kingdom was for the senior military commander of U.S. troops in Hawai‘i, Admiral Skerrett, Commander of the U.S.S. Boston, to take control of the Hawaiian Kingdom governmental apparatus, called a military government, and continue to administer Hawaiian Kingdom law until there is a treaty of peace. U.S. Army Field Manual 27-5 states:

The term “military government” as used in this manual is limited to and defined as the supreme authority exercised by an armed occupying force over the lands, properties, and inhabitants of an enemy, allied, or domestic territory. Military government is exercised when an armed force has occupied such territory, whether by force or agreement, and has substituted its authority for that of the sovereign or previous government. The right of control passes to the occupying force limited only by the rules of international law and established customs of war.

But Admiral Skerrett did not comply with international law and the insurgents were allowed to continue to pretend that they were the legitimate government, ever after President Cleveland told the Congress on December 18, 1893, that the “provisional government owes its existence to an armed invasion by the United States.” Five years later, in 1898, the United States unilaterally annexed the Hawaiian Islands in violation of Hawaiian State sovereignty and international law. According to U.S. Army Field Manual 27-10:

Being an incident of war, military occupation confers upon the invading force the means of exercising control for the period of occupation. It does not transfer the sovereignty to the occupant, but simply the authority or power to exercise some of the rights of sovereignty. The exercise of these. rights results from the established power of the occupant and from the necessity of maintaining law and order, indispensable both to the inhabitants and to the occupying force. It is therefore unlawful for a belligerent occupant to annex occupied territory or to create a new State therein while hostilities are still in progress.

After illegally annexing the Hawaiian Islands without a treaty with the Hawaiian Kingdom, the United States began to unlawfully impose its laws throughout the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom. The imposition of the Occupying State’s laws over the territory of an Occupied State is the war crime of usurpation of sovereignty during military occupation. This war crime had a devastating effect on the health of the native Hawaiian people who had universal healthcare, at no cost, at Queen’s Hospital, and native Hawaiian access to lands for their homes and businesses.

Queen’s Hospital was established in 1859 by King Kamehameha IV and Queen Emma under the 1859 Hospital Act. Its purpose was to provide universal health care, at no cost, for all native Hawaiians. Under its charter the Monarch would serve as President of a Board of Trustees comprised of ten persons appointed by the government and ten persons elected by the corporation’s shareholders.

The Hawaiian government appropriated funding for the maintenance of the hospital. “Native Hawaiians are admitted free of charge, while foreigners pay from seventy-five cents to two dollars a day, according to accommodations and attendance (Henry Witney, The Tourists’ Guide through the Hawaiian Islands Descriptive of Their Scenes and Scenery (1895), p. 21).” It wasn’t until the 1950’s and 1960’s that the Nordic countries followed what the Hawaiian Kingdom had already done with universal health care.

In 1909, the government’s interest in Queen’s Hospital was severed and native Hawaiians would no longer be admitted free of charge. The new Board of Trustees changed the 1859 charter where it stated, “for the treatment of indigent sick and disabled Hawaiians” to “for the treatment of sick and disabled persons.” Gradually native Hawaiians were denied health care unless they could pay. This led to a crisis of native Hawaiian health today. Queen’s Hospital, now called Queen’s Health Systems, currently exists on the islands of O‘ahu, Molokai, and Hawai‘i.

A report by the Office of Hawaiian Affairs in 2017 stated, “Today, Native Hawaiians are perhaps the single racial group with the highest health risk in the State of Hawai‘i. This risk stems from high economic and cultural stress, lifestyle and risk behaviors, and late or lack of access to health care (Native Hawaiian Health Fact Sheet 2017, p. 2).” Hawaiians should not have died due to “late or lack of health care” because Queen’s Hospital was an institution that provided health care at no cost.

Another right of native Hawaiians, under Hawaiian Kingdom law, was access to government land for a home and/or business. Under the 1850 Kuleana Act, which has not been repealed by the Hawaiian Legislature and remained a law in 1893, native Hawaiians can receive from the Minister of the Interior up to 50 acres in fee-simple at $.50 an acre. According to the inflation calculator, $.50 in 1893 would be $20 today. So, for a quarter acre for a home, a native Hawaiian need only to pay $5.

According to the U.S. Census of 2022, there are 714,847 native Hawaiians. The majority of native Hawaiians presently reside in the United States. The reason for native Hawaiians moving to the United States is attributed to Hawai‘i’s high cost of living.

On February 20, 2024, Hawai‘i News Now did a story “Hawaii’s high cost of living testing patience of residents, poll shows.” The report interviewed two native Hawaiians, Patricia Pele and Kahi Kaonohi.

Patricia Pele grew up on Molokai and wanted to pursue a career in the state after graduating from Chaminade, but ultimately chose to move.

She and her partner Nathan Estes previously rented a one-bedroom apartment in Aiea for $1,700 a month.

They now pay less than half that for a home in Dayton, Ohio.

“We have a four-bedroom house and our mortgage is a little bit less than $700 a month,” Estes said. “Two full baths, a covered garage with extra driveway space.”

Pele acknowledges she misses home and struggled to adjust, but financial flexibility outweighed being homesick.

“You’ll get happy in paradise, but you’ll also have to pay that price,” Pele said. “It’s unfortunate that it takes multi-generational income under one roof, multiple jobs. I think all my friends had at least two jobs if not three and that was with another spouse or significant other.”

For lifelong Windward Oahu native and musician Kahi Kaonohi, leaving the islands isn’t an option.

“Hawaii to me is my home and it’s a special place,” Kaonohi said. “I just feel that I have to do and my wife, we just have to do what we have to do to live here.”

Kaonohi and his wife have six kids and 10 grandchildren.

He says all but one of his children still live on Oahu and while he’s retired, they’re in the daily grind.

“Every day items that used to be $1.50 is now $4.75, how did that happen?,” Kaonohi said. “It’s still the same product. How did it go for four dollars more?”

According to U.S. News, “Cost of Living: How to Calculate How Much You Need,” it explains how to calculate the cost of living.

Simply add up all of your monthly fixed expenses, like rent or a mortgage payment, and your variable expenses, such as groceries and gas costs. Also factor in occasional but expected purchases, such as new tires. The resulting amount, assuming you aren’t going to debt every month, is your cost of living.

Under the American occupation, Hawai‘i’s economy is the combination of inflated high costs for housing, healthcare and groceries. To live comfortably in Honolulu, you will need an annual income of $200,000. The U.S. Census, in 2019, had the median household income at around $80,000. According to Payscale.com, the cost of living in Honolulu is 84% higher than the average in the United States, housing is 214% higher, utilities is 42% higher, and groceries is 50% higher. On O‘ahu, the median price for a home is $1,100,000 and the median price for an apartment is $510,000. These high costs for home purchasing forces people to rent. The average median monthly rent for all islands is $3,000.

Contributing to the high cost of groceries, Hawai‘i imports 85-90% of food. The money it costs to bring this food, by sea or air, to the Hawaiian Islands is passed on to the consumer. In other words, the cost of fuel and labor on the planes or ships that carry the food, in addition to the cost of producing the food itself, is included in the costs to the buyer of the food.

In 1893, the Hawaiian Kingdom had the reverse where it produced over 90% of its own food for the Hawaiian economy. According to the Hawaiian Almanac and Annual for 1893, the Hawaiian Kingdom, in 1891, exported 58% of its goods and imported 42%. The major articles for exports from 1862-1891 were sugar, molasses, rice, coffee, bananas, goat skins, hides, tallow, wool, betel leaves, sheep skins, guano, fruit, pineapples, vegetables, plants, and seeds. The major trading partners with the Hawaiian Kingdom from 1885 to 1893 were the United States, Great Britain, Germany, British Columbia, Australia, New Zealand, China, Japan and France. The Hawaiian Kingdom had a healthy economy.

The failure for the United States to maintain this status quo during the American occupation is not only a gross violation of international law but it, consequently, placed the native Hawaiian population in a dire situation in their own country. In his memorandum, as Minister of the Interior, Dr. Keanu Sai states:

While the State of Hawai‘i has yet to transform itself into a Military Government and proclaim the provisional laws, as proclaimed by the Council of Regency, that brings Hawaiian Kingdom laws up to date, Hawaiian Kingdom laws as they were prior to January 17, 1893, continue to exist. The greatest dilemma for aboriginal Hawaiians today is having a home and health care. Average cost of a home today is $820,000.00. And health care insurance for a family of 4 is at $1,500 a month. According to the Office of Hawaiian Affairs’ Native Hawaiian Health Fact Sheet 2017, “Today, Native Hawaiians are perhaps the single racial group with the highest health risk in the State of Hawai‘i. This risk stems from high economic and cultural stress, lifestyle and risk behaviors, and late or lack of access to health care.”

Under Hawaiian Kingdom laws, aboriginal Hawaiian subjects are the recipients of free health care at Queen’s Hospital and its outlets across the islands. In its budget, the Hawaiian Legislative Assembly would allocate money to the Queen’s Hospital for the healthcare of aboriginal Hawaiian subjects. The United States stopped allocating moneys from its Territory of Hawai‘i Legislature in 1909. Aboriginal Hawaiian subjects are also able to acquire up to 50 acres of public lands at $20.00 per acre under the 1850 Kuleana Act. With the current rate of construction costs, which includes building material and labor, an aboriginal Hawaiian subject can build 3-bedroom, 1-bath home for $100,000.00.

Hawaiian Kingdom laws also provide for fishing rights that extend out to the first reef or where there is no reef, out to 1 mile, exclusively for all Hawaiian subjects and lawfully resident aliens of the land divisions called ahupua‘a or ‘ili. From that point out to 12 nautical miles, all Hawaiian subjects and lawfully resident aliens have exclusive access to economic activity, such as mining underwater resources and fishing. Once the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea is acceded to by the Council of Regency, this exclusive access to economic activity will extend out to 200 miles called the Exclusive Economic Zone.

Major General Kenneth Hara and Brigadier General Stephen Logan denied all native Hawaiians their legal right to access free health care at Queen’s Hospital throughout the islands, and denied them their legal right to access government land to build a home or business, because they were both willfully derelict in their duty to establish a military government of Hawai‘i in accordance with the Law of Armed Conflict—international humanitarian law, U.S. Department of Defense Directive 5100.01, and Army Regulations—FM 27-5 and FM 27-10. Thus, becoming war criminals for the war crime by omission.

This duty to establish a military government is now on the shoulders of Colonel Wesley Kawakami, Commander of the 29th Infantry Brigade of the Hawai‘i Army National Guard. He has until 12 noon on August 19, 2024, to transform the State of Hawai‘i into a military government of Hawai‘i. The Council of Regency’s Operational Plan for transitioning the State of Hawai‘i into a Military Government will provide Colonel Kawakami guidance to do so. If Colonel Kawakami is derelict in his duty and consequently commits the war crime by omission, it will fall upon the next officer in the chain of command to perform. This will continue until someone in the Army National Guard performs their military duty.

Dr. Keanu Sai on Keep It Aloha Podcast

Dr. Keanu Sai Presented a History of the Kāʻei or Sash of Liloa at Bishop Museum on July 31st

The Bishop Museum invited Dr. Keanu Sai to present a history of the kāʻei or sash of Līloa who was King of Hawaiʻi Island in the fifteenth century. Here follows the speech that Dr. Sai gave yesterday at Bishop Museum in celebration of the Hawaiian Kingdom national holiday Restoration Day (Lā Hoʻihoʻi).

It is truly an honor for me to be here with you on this Hawaiian Kingdom national holiday of Restoration Day or Lā Ho‘iho‘i and share with you a bit of history of the kāʻei or sash of Līloa and its direct link as a royal emblem of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

Ancient human society was comprised of tribes or bands that were either subsumed or grew into what anthropologists have come to call ancient States, which pre-dates the Westphalian States of the 17th century that was the genesis of current understanding of States under international law today.

Ancient States, which Hommon calls primary States, “are generally believed to have developed in six widely distributed regions of the world: Mesopotamia, Egypt, the Indus Valley, China, Mesoamerica, and Andean South America.” To these regions, Hommon and Kirch add the North Pacific and the emergence of the ancient Hawaiian State from the fifteenth century with “centralized, active leadership based on political power, delegation of such power through a formal bureaucracy, and territorial expansion by conquest warfare.”

According to Kirch, “the Hawaiians had invented divine kingship, a hallmark of archaic states.” Political science and law today distinguishes between the State and its government, but this distinction pertains to the Westphalian States that arose in Europe since 1648, and not the ancient States that Hommon and Kirch refer to.

When Captain James Cook arrived in the islands in 1778, he witnessed a phenomenon not seen in other parts of the Pacific he previously visited. What he observed was a society whose governmental structure was centralized, organized, and disciplined. He wrote, “I have no where in this Sea seen such a number of people assembled at one place.” Kirch concludes, the “combination of quantitative and qualitative criteria bolster the case that the late Hawaiian polities as encountered by Cook and other early European explorers fit conformably with the pattern of primary archaic states known for other regions of the world.”

Captain James King, who served under Cook, provides an eyewitness account of the Chiefs of that time. Captain King admired Hawaiian nobility and described their regal appearance. “These chiefs were men of strong and well-proportioned bodies, and of countenances remarkably pleasing. Kana‘ina especially, whose portrait Mr. Webber has drawn, was one of the finest men I ever saw. He was about six feet high, had regular and expressive features, with lively, dark eyes; his carriage was easy, firm, and graceful.”

Captain King also stated that Kana‘ina “was very inquisitive after our customs and manners; asked after our King; the nature of our government; our numbers; the method of building our ships; our houses; the produce of our country; whether we had wars; with whom; and on what occasions; and in what manner they were carried on; who was our God; many other questions of the same nature, which indicated an understanding of great comprehension.” I should also note that Kana‘ina is my fourth great grandfather who is also known along with another chief for causing the demise of Captain Cook.

Kana‘ina was a direct descendant of Līloa, King of Hawai‘i island in the 15th century. His father being Keawe ‘Opala and his grandfather being Alapa‘i Nui, both kings of Hawai‘i island. Since Pili Ka‘ea, progenitor of the line of Hawai‘i Island Kings, there were two royal emblems, the spittal-vessels called ipu kuha and the crown called the kahili.

Added to these royal emblems in the 15th century was the kā‘ei or sash of Līloa we see here this evening. Līloa ordered the making of the sash whom his son Umialiloa received when he ascended to the throne after defeating his half-brother, Hākau, in battle. The dimensions of the kā‘ei are 4.5 inches wide and 11 feet in length. As with feather capes and cloaks, the kāʻei consists of feathers tied to a netting of olona fiber. The read feathers of the ʻiʻiwi bird and the yellow of the ōʻō bird, along with rows of teeth, it creates an object that is still stunning to behold nearly six centuries after its creation. Carbon dating of feathers that naturally separated itself from the kāʻei ranged from 1406 to 1450 A.D.

The kāʻei eventually came into the possession of Kamehameha the Great, progenitor of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and it can be seen adorned on him as seen on his statue that fronts Ali‘iolani Hale across from the palace.

In 1794, Kamehameha became a part of the British Empire where he continued to be king of a British protectorate. By 1810, Kamehameha consolidated the former kingdoms of Maui and Kauaʻi into one kingdom that came to be known as the Hawaiian Kingdom. After his death in 1819, the ipu kuha, the kahili and the kāʻei descended to Kamehameha II. And after the death of Kamehameha II in 1824 these royal emblems descended to Kamehameha III.

In 1840, Kamehameha III transformed the Hawaiian Kingdom into a constitutional monarchy while still owing allegiance to the British Crown. Based on claims by the British Consul Richard Charlton that the rights of British subjects were being violated by the Hawaiian government, a British warship, HBMS Carysfort, under the command of Captain Lord Paulet, entered Honolulu harbor on February 10, 1843. Paulet eventually seized control of the Hawaiian government on February 25th after threatening to level Honolulu with cannon fire. Kamehameha III was forced to surrender the kingdom but did so under written protest and pending the outcome of the mission of his diplomats that were dispatched to the United States and Europe the previous year to seek recognition of Hawaiian independence.

News of Paulet’s action reached Admiral Richard Thomas of the British Admiralty, and he sailed from the Chilean port of Valparaiso and arrived in Honolulu on July 25, 1843. After a meeting with Kamehameha III, Admiral Thomas determined that Charlton’s complaints did not warrant a British takeover and ordered the restoration of the Hawaiian government, which took place in a grand ceremony on July 31, 1843, at a place that has come to be known today as Thomas Square. At a thanksgiving service after the ceremony, Kamehameha III proclaimed before a large crowd, ua mau ke ea o ka ‘āina i ka pono (the life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness). The King’s statement became the national motto. July 31st also became a national holiday in the Hawaiian Kingdom, and it is why we are here today at the Bishop Museum.

Kamehameha III’s diplomats eventually succeeded in achieving recognition of Hawaiian independence. On November 28, 1843, both Great Britain and France, at the Court of London, jointly recognized the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State. The United States followed the next year on July 6, 1844. In the nineteenth century, the Hawaiian Kingdom was one of only forty-four independent States that comprised the family of nations. Today the United Nations is comprised of 196 independent States.

The Hawaiian Kingdom became one of the most progressive countries in the world with land reform, universal health care for native Hawaiians at no cost at Queen’s hospital, and universal education for the population at common schools, secondary schools and colleges. Dr. Sun Yat Sen, the father of modern China, and who received his education at Iolani College and Punahou between 1879 and 1883, told a reporter when he returned to Hawai‘i, “This is my Hawaii. Here I was brought up and educated; and it was here that I came to know what modern, civilized governments are like and what they mean.”

After the death of Kamehameha III on December 15, 1854, his wife, the Queen consort Kalama, inherited the kāʻei. When she passed away on September 20, 1870, her mother’s brother and adopted father, High Chief Charles Kana‘ina, father of King Lunalilo, inherited the kāʻei.

On March 13, 1877, Charles Kana‘ina died and probate proceeding ensued until 1882. At one of the auctions of the estate in 1877, Lucy Peabody, who would later become a Lady in Waiting to Queen Lili‘uokalani, stated that King Kālakaua retrieved the kāʻei before it could be auctioned. Thus, the kāʻei became a royal emblem of not just the Kamehameha Dynasty but also the Kālakaua Dynasty.

The following month, on April 10, 1877, Kālakaua received approval from the Nobles of the Legislative Assembly that Princess Lili‘uokalani would be his heir apparent. After the death of the King in 1891, Princess Lili‘uokalani became Queen Lili‘uokalani.

Preparing to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Hawaiian independence, a dire situation would take place reminiscent of the British takeover in 1843. On January 16, 1893, U.S. resident Minister John Stevens ordered the landing of marines that eventually led to the takeover of the Hawaiian government the following day. Of note is that the Queen did not surrender to the insurgency but rather to the United States and called upon the President to investigate the actions taken by their resident Minister and the Admiral that landed of U.S. troops.

After President Cleveland conducted a presidential investigation he told the Congress on December 18, 1893, “And so it happened that on the 16th day of January, 1893, between four and five o’clock in the afternoon, a detachment of marines from the United States steamer Boston, with two pieces of artillery, landed at Honolulu. The men upwards of 160 in all, were supplied with double cartridge belts filled with ammunition and with haversacks and canteens, and were accompanied by a hospital corps with stretchers and medical supplies. This military demonstration upon the soil of Honolulu was of itself and act of war.”

President Cleveland also reported, “It has been the boast of our Government that it seeks to do justice in all things without regard to the strength or weakness of those with whom it deals. I mistake the American people if they favor the odious doctrine that there is no such thing as international morality, that there is one law for a strong nation and another for a weak one, and that even by indirection a strong power may with impunity despoil a weak one of its territory. By an act of war, committed with the participation of a diplomatic representative of the United States and without authority of Congress, the Government of a feeble but friendly and confiding people has been overthrown. President Cleveland concluded that “A substantial wrong has thus been done which a due regard for our national character as well as the rights of the injured people requires we should endeavor to repair.”

The President entered into a treaty with the Queen to restore her to the office of Monarch, but because of political wrangling in the Congress and the lust for Pearl Harbor, the agreement was not carried out. Five years later, on July 7, 1898, at the height of the Spanish-American War, President McKinley signed into American law a joint resolution for annexing the Hawaiian Islands. In 1910, Queen Lili‘uokalani, with the kāʻei in her possession, provided it to the Bishop Museum.

However, the story of the kāʻei, being one of the royal emblems of the Hawaiian Kingdom, is not finished. ‘A‘ole pau.

According to international law, the United States military overthrow of the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893 did not affect the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State. Nor did the annexation of the Hawaiian Islands by the Congress affect the Hawaiian State because a congressional joint resolution is a legislative act that can only operate within United States territory. In other words, American laws have no effect beyond the borders of the United States.

The United States could only have a acquired the Hawaiian Kingdom’s sovereignty by a treaty. There is no treaty. Only American laws being unlawfully imposed throughout Hawaiian territory. The United States could no more enact law annexing Hawai‘i in 1898 than it could enact a law today annexing Canada, Mexico or Cuba. It is absurd to think otherwise.

In 1997, the Hawaiian government was restored as a Regency under Hawaiian constitutional law and the legal doctrine of necessity. And in 1999, an international dispute was submitted for arbitration at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Netherlands called Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom. The United States and other countries established the Permanent Court in 1899 to resolve international disputes that States may have with each other, or disputes between a State and an international organization, or a dispute between a State and private entity. In other words, the Permanent Court is only authorized to create an arbitration tribunal if one of the parties to the dispute is a State under international law.

On the Permanent Court’s website it describes the case as “Lance Paul Larsen, a resident of Hawaii, brought a claim against the Hawaiian Kingdom by its Council of Regency on the grounds that the Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom is in continual violation of: (a) its 1849 Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation with the United States of America, as well as the principles of international law laid down in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 1969 and (b) the principles of international comity, for allowing the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws over the claimant’s person within the territorial jurisdiction of the Hawaiian Kingdom.”

Before the Permanent Court could form the arbitration tribunal to resolve this dispute it had to confirm that the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist as a State since the nineteenth century despite the overthrow of its government in 1893 and despite the American annexation in 1898. The Permanent Court did just that and it also recognized that the Council of Regency is its government. And more importantly, the United States did not protest or object to the Permanent Court’s recognition of the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom. In fact, the United States, through its embassy in the Netherlands, entered into an agreement with the Hawaiian Kingdom so that it could have access to all records and pleadings of the case.

Today is not just to celebrate Restoration Day or La Ho‘iho‘i, but it is also to celebrate that a sequence of events has begun today for the State of Hawai‘i to begin to comply with the international law of occupation, which will eventually bring 131 years of an unlawful and prolonged occupation of a sovereign and independent State to an end.

Despite over a century of revisionist history, the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a sovereign State is grounded in the very same principles that the United States and every other State have relied on for their own legal existence. The Hawaiian Kingdom is a magnificent story of perseverance and continuity.

Mahalo.

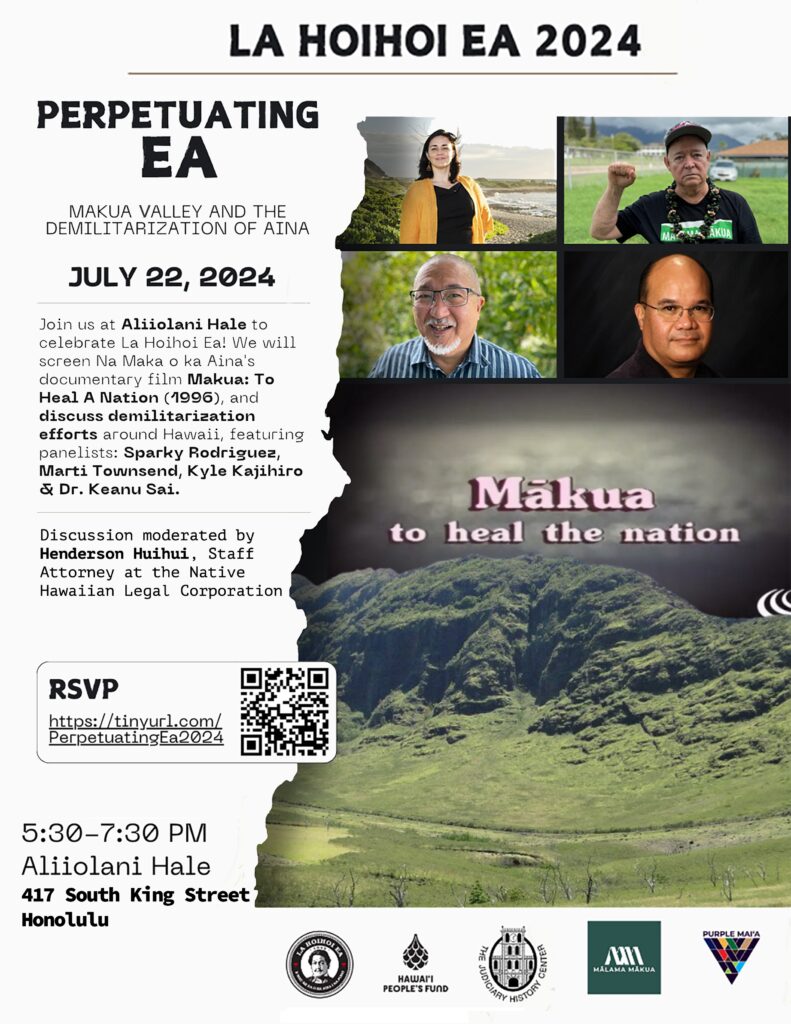

Dr. Keanu Sai to be a Panelist on the Demilitarization of Hawai‘i

The Seat of Hawaiian Sovereignty Remains Undisturbed Despite the American Occupation

The bedrock of international law is the sovereignty of an independent State. Black’s Law dictionary defines sovereignty as the “supreme, absolute, and uncontrollable power by which any independent state is governed.” For the purposes of international law, Wheaton explains:

Sovereignty is the supreme power by which any State is governed. This supreme power may be exercised either internally or externally. Internal sovereignty is that which is inherent in the people or any State, or vested in its ruler, by its municipal constitution or fundamental laws. This is the object of what has been called internal public law […], but which may be more properly be termed constitutional law. External sovereignty consists in the independence of one political society, in respect to all other political societies. It is by the exercise of this branch of sovereignty that the international relations of one political society are maintained, in peace and in war, with all other political societies. The law by which it is regulated has, therefore, been called external public law […], but may more properly be termed international law.

In the Island of Palmas arbitration, which was a dispute between the United States and the Netherlands, the arbitrator explained that “Sovereignty in the relations between States signifies independence. Independence in regard to a portion of the globe is the right to exercise therein, to the exclusion of any other State, the functions of a State.” And in the S.S. Lotus case, which was a dispute between France and Turkey, the Permanent Court of International Justice stated:

Now the first and foremost restriction imposed by international law upon a State is that—failing the existence of a permissive rule to the contrary—it may not exercise its power in any form in the territory of another State. In this sense jurisdiction is certainly territorial; it cannot be exercised by a State outside its territory except by virtue of a permissive rule derived from international custom or from a convention [treaty].

The permissive rule under international law that allows one State to exercise authority over the territory of another State is Article 43 of the 1907 Hague Regulations and Article 64 of the Fourth Geneva Convention, that mandates the occupant to establish a military government to provisionally administer the laws of the occupied State until there is a treaty of peace. For the past 131 years, there has been no permissive rule of international law that allows the United States to exercise any authority in the Hawaiian Kingdom, which makes the prolonged occupation illegal under international law.

As the arbitral tribunal, in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, noted in its award, “in the nineteenth century the Hawaiian Kingdom existed as an independent State recognized as such by the United States of America, the United Kingdom and various other States, including by exchanges of diplomatic or consular representatives and the conclusion of treaties.” The scope of Hawaiian sovereignty is sweeping. According to §6 of the Hawaiian Civil Code:

The laws are obligatory upon all persons, whether subjects of this kingdom, or citizens or subjects of any foreign State, while within the limits of this kingdom, except so far as exception is made by the laws of nations in respect to Ambassadors or others. The property of all such persons, while such property is within the territorial jurisdiction of this kingdom, is also subject to the laws.

Property within the territorial jurisdiction of the Hawaiian Kingdom includes both real estate and personal property. Hawaiian sovereignty over the population, whether Hawaiian subjects or citizens or subjects of any foreign State, is expressed in the Penal Code. Under Chapter VI—Treason, the statute, which is in line with international law, states:

1. Treason is hereby defined to be any plotting or attempt to dethrone or destroy the King, or the levying of war against the King’s government, or the adhering to the enemies thereof, giving them aid and comfort, the same being done by a person owing allegiance to this kingdom.

2. Allegiance is the obedience and fidelity due to the kingdom from those under its protection.

3. An alien, whether his native country be at war or at peace with this kingdom, owes allegiance to this kingdom during his residence therein, and during such residence, is capable of committing treason against this kingdom.

4. Ambassadors and other ministers of foreign states, and their alien secretaries, servants and members of their families, do not owe allegiance to this kingdom, though resident therein, and are not capable of committing treason against this kingdom.

When the Hawaiian Kingdom Government conditionally surrendered to the United States forces on January 17, 1893, the action taken did not transfer Hawaiian sovereignty but merely relinquished control of Hawaiian sovereignty because of the American invasion and occupation. According to Benvenisti:

The foundation upon which the entire law of occupation is based is the principle of inalienability of sovereignty through unilateral action of a foreign power, whether through the actual or the threatened use of force, or in any way unauthorized by the sovereign. Effective control by foreign military force can never bring about by itself and valid transfer of sovereignty. Because occupation does not transfer sovereignty over the territory to the occupying power, international law must regulate the inter-relationships between the occupying force, the ousted government, and the local inhabitants for the duration of the occupation. […] Because occupation does not amount to sovereignty, the occupation is also limited in time and the occupant has only temporary managerial powers, for the period until a peaceful solution is reached. During that limited period, the occupant administers the territory on behalf of the sovereign. Thus the occupant’s status is conceived to be that of a trustee.

The occupant’s ‘managerial powers’ is exercised by a military government over the territory of the occupied State that the occupant is in effective control. The military government would need to be in effective control of the territory in order to effectively enforce the laws of the occupied State. Without effective control there can be no enforcement of the laws.

The Hawaiian government’s surrender that transferred effective control over the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom to the American military did not transfer Hawaiian sovereignty. U.S. Army FM 27-10 explicitly states, “Being an incident of war, military occupation confers upon the invading force the means of exercising control for the period of occupation. It does not transfer the sovereignty to the occupant, but simply the authority or power to exercise some of the rights of sovereignty.”

The United States never possessed sovereignty over the Hawaiian Islands. It remained undisturbed for over a century, and in 1997 when the Hawaiian Kingdom government was restored as a Regency, Hawaiian sovereignty came to the forefront as the foundation for the existence of the Regency and the application of the law of occupation.

Restoration of Hawaiian sovereignty needs to be removed from the conversations because you cannot restore what was never taken. And restoring the Hawaiian Kingdom government also needs to be removed from the conversations because the government was already restored in 1997 as a Regency, in an acting capacity, until the Legislature can be reconvened to elect by ballot a lawful Regency according to Article 33 of the 1864 Constitution, as amended. The doctrine of necessity and Hawaiian constitutional law provides the legal basis for the Regency to serve in an acting role.

What should become a part of the conversation is the duty of the State of Hawai‘i Adjutant General to comply with the law of occupation by establishing a military government to temporarily administer the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom as they were prior to the American invasion and also the provisional laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom proclaimed by the Council of Regency on October 10, 2014. These provisional laws shall be all Federal, State, and County laws that “do not run contrary to the express, reason and spirit of the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom prior to July 6, 1887, the international law of occupation and international humanitarian law, and if it be the case they shall be regarded as invalid and void.” The Minister of the Interior published a memorandum on the formula to be used in determining whether American laws can be considered provisional laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

Royal Order of Kamehameha I Calls Upon Major General Hara to Transform State of Hawai‘i into a Military Government

On June 15, 2024, the Royal Order of Kamehameha I sent a letter to State of Hawai‘i Adjutant General Major General Kenneth Hara to perform his duty of transforming the State of Hawai‘i into a Military Government. Here is a link to download the letter.

Aloha Major General Hara:

We the members of the Royal Order of Kamehameha I (including Na Wahine O Kamehameha), was established in the early 1900s to maintain a connection to our country, the Hawaiian Kingdom, despite the unlawful overthrow of our country’s government on January 17, 1893, by the United States.

Our people have suffered greatly in the aftermath of the overthrow, but we, as Native Hawaiian subjects, have survived. Our predecessors, who established the Royal Order of Kamehameha I, had a national consciousness of their country that we didn’t have because of the Americanization of these islands. We, today, were taught that our country no longer existed and that we are now American citizens. We now know that this is not true.

When the Government was restored in 1997, the Council of Regency embarked on a monumental task to ho‘oponopono (right the wrong) from a legal standpoint. Their success to get the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague, Netherlands, to recognize the continued existence of our country and the Council of Regency as our government was no small task. When the Council of Regency returned from the Netherlands in 2000, they embarked on an educational campaign to restore the national consciousness of the Hawaiian Kingdom in the minds of its people. This led to classes being taught on the American occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom at the University of Hawai‘i, High Schools, Middle Schools, Elementary Schools, and Preschools throughout the Hawaiian Islands.

In 2018, the Hawai‘i State Teachers Association was able to get their resolution passed at the annual conference of the National Education Association in Boston, Massachusetts. The resolution stated, “The NEA will publish an article that documents the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Monarchy in 1893, the prolonged illegal occupation of the United States in the Hawaiian Kingdom and the harmful effects that this occupation has had on the Hawaiian people and resources of the land.” The HSTA asked Dr. Keanu Sai to write three articles, which were published on the NEA website. Dr. Sai is the Chairman of the Council of Regency, and he led the legal team for the Hawaiian Kingdom at the Permanent of Court of Arbitration in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom.

Because of this educational campaign, we are now aware that our country still exists and, as a people, we must owe allegiance to the Hawaiian Kingdom as our predecessors did. This is not a choice, but an obligation as Hawaiian subjects. We also acknowledge that the Council of Regency is our government that was lawfully established under extraordinary circumstances, and we support its effort to bring compliance with the law of occupation by the State of Hawai‘i on behalf of the United States, which will eventually bring the American occupation to close. When this happens, our Legislative Assembly will be brought into session so that Hawaiian subjects can elect a Regency of our choosing. The Council of Regency is currently operating in an acting capacity that is allowed under Hawaiian law.

We have read the Minister of the Interior’s memorandum dated April 26, 2024 (https://hawaiiankingdom.org/pdf/Memo_re_Rights_of_Hawaiians_(4.26.24).pdf), and the Council of Regency’s Operational Plan for the State of Hawai‘i to transform into a Military Government (https://hawaiiankingdom.org/pdf/HK_Operational_Plan_of_Transition.pdf), and we support this plan. After watching Dr. Sai’s presentation to the Maui County Council on March 6, 2024 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X-VIA_3GD2A), we were made aware of your reluctance to carry out your duty to transform the State of Hawai‘i into a Military Government.

Because of the high cost of living brought here because of the unlawful American presence, the majority of Native Hawaiians now reside in the United States. The U.S. Census reported that in 2020, that of the total of 680,442 Native Hawaiians, 53 percent live in the United States. The driving factors that led to the move were not being able to afford a home and adequate health care. Dr. Sai, as the Minister of the Interior, clearly explains this in his memorandum where he states,

While the State of Hawai‘i has yet to transform itself into a Military Government and proclaim the provisional laws, as proclaimed by the Council of Regency, that brings Hawaiian Kingdom laws up to date, Hawaiian Kingdom laws as they were prior to January 17, 1893, continue to exist. The greatest dilemma for aboriginal Hawaiians today is having a home and health care. Average cost of a home today is $820,000.00. And health care insurance for a family of 4 is at $1,500 a month. According to the Office of Hawaiian Affairs’ Native Hawaiian Health Fact Sheet 2017, “Today, Native Hawaiians are perhaps the single racial group with the highest health risk in the State of Hawai‘i. This risk stems from high economic and cultural stress, lifestyle and risk behaviors, and late or lack of access to health care.”

Under Hawaiian Kingdom laws, aboriginal Hawaiian subjects are the recipients of free health care at Queen’s Hospital and its outlets across the islands. In its budget, the Hawaiian Legislative Assembly would allocate money to the Queen’s Hospital for the healthcare of aboriginal Hawaiian subjects. The United States stopped allocating moneys from its Territory of Hawai‘i Legislature in 1909. Aboriginal Hawaiian subjects are also able to acquire up to 50 acres of public lands at $20.00 per acre under the 1850 Kuleana Act. With the current rate of construction costs, which includes building material and labor, an aboriginal Hawaiian subject can build 3-bedroom, 1-bath home for $100,000.00.

Hawaiian Kingdom laws also provide for fishing rights that extend out to the first reef or where there is no reef, out to 1 mile, exclusively for all Hawaiian subjects and lawfully resident aliens of the land divisions called ahupua‘a or ‘ili. From that point out to 12 nautical miles, all Hawaiian subjects and lawfully resident aliens have exclusive access to economic activity, such as mining underwater resources and fishing. Once the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea is acceded to by the Council of Regency, this exclusive access to economic activity will extend out to 200 miles called the Exclusive Economic Zone.

On behalf of the members of the Royal Order, I respectfully call upon you to carry out your duty to proclaim the transformation of the State of Hawai‘i into a Military Government so that all Hawaiian subjects, and their families, would be able to exercise their rights secured to them under Hawaiian Kingdom law and protected by the international law of occupation. We urge you to work with the Council of Regency in making sure this transition is not only lawful but is done for the benefit of all Hawaiian subjects that are allowed under Hawaiian Kingdom law, the 1907 Hague Regulations and the 1949 Fourth Geneva Convention.

International Law Journal Publishes Articles by the Head and Deputy Head of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s Royal Commission of Inquiry

The International Review of Contemporary Law released its volume 6, no. 2, earlier this month. The theme of this journal is “77 Years of the United Nations Charter.” The Head, Dr. Keanu Sai, and Deputy Head, Professor Federico Lenzerini, of the Royal Commission of Inquiry that investigates war crimes and human rights violations committed in the Hawaiian Kingdom, each had an article published in the journal.

Dr. Sai’s article is titled “All States have a Responsibility to Protect their Population from War Crimes—Usurpation of Sovereignty During Military Occupation of the Hawaiian Islands.” Dr. Sai’s article opened with:

At the United Nations World Summit in 2005, the Responsibility to Protect was unanimously adopted. The principle of the Responsibility to Protect has three pillars: (1) every State has the Responsibility to Protect its populations from four mass atrocity crimes—genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and ethnic cleansing; (2) the wider international community has the responsibility to encourage and assist individual States in meeting that responsibility; and (3) if a state is manifestly failing to protect its populations, the international community must be prepared to take appropriate collective action, in a timely and decisive manner and in accordance with the UN Charter. In 2009, the General Assembly reaffirmed the three pillars of a State’s responsibility to protect their populations from war crimes and crimes against humanity. And in 2021, the General Assembly passed a resolution on “The responsibility to protect and the prevention of genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity.” The third pillar, which may call into action State intervention, can become controversial.

Rule 158 of the International Committee of the Red Cross Study on Customary International Humanitarian Law specifies that “States must investigate war crimes allegedly committed by their nationals or armed forces, or on their territory, and, if appropriate, prosecute the suspects. They must also investigate other war crimes over which they have jurisdiction and, if appropriate, prosecute the suspects.” This “rule that States must investigate war crimes and prosecute the suspects is set forth in numerous military manuals, with respect to grave breaches, but also more broadly with respect to war crimes in general.”