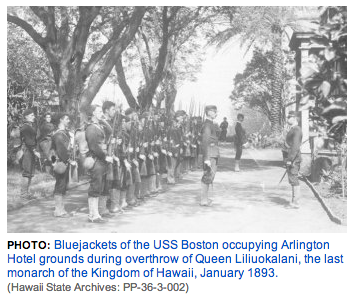

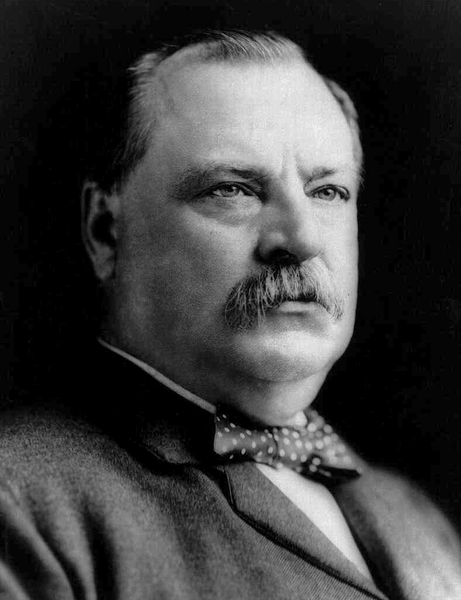

After investigating the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government by United States forces on January 17, 1893, President Cleveland notified the Congress on December 18, 1893, “When our Minister [diplomat] recognized the provisional government the only basis upon which it rested was the fact that the Committee of Safety had in the manner above stated declared it to exist. It was neither a government de facto nor de jure (p. 453).”

After investigating the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government by United States forces on January 17, 1893, President Cleveland notified the Congress on December 18, 1893, “When our Minister [diplomat] recognized the provisional government the only basis upon which it rested was the fact that the Committee of Safety had in the manner above stated declared it to exist. It was neither a government de facto nor de jure (p. 453).”

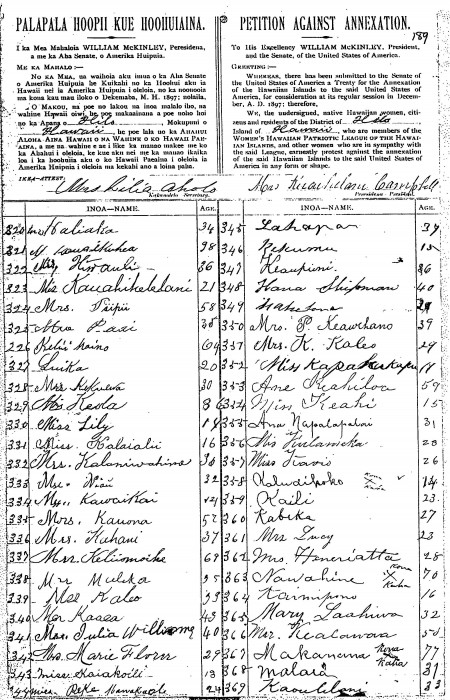

The Committee of Safety was a group of thirteen insurgents that sought the protection of United States troops from the American diplomat, John Stevens, assigned to the Hawaiian Kingdom when they would declare themselves to be a provisional government. The insurgents sought protection from being apprehended for the crime of treason by law enforcement of the Hawaiian Kingdom. As soon as the Committee of Safety declared themselves to be the provisional government of the Hawaiian Kingdom, the American diplomat extended de facto recognition. De facto is a government “in fact” where it is in complete control of all governmental machinery, while de jure is a government “in law” established through the normal course of a country’s legal system. Cleveland concluded, “the Government of the Queen…was undisputed and was both the de facto and the de jure government (p. 451).” He explained to the Congress,

“That it was not in such possession of the Government property and agencies as entitled it to recognition… Nevertheless, this wrongful recognition by our Minister placed the Government of the Queen in a position of most perilous perplexity. On the one hand she had possession of the palace, of the barracks, and of the police station, and had at her command at least five hundred fully armed men and several pieces of artillery. Indeed, the whole military force of her kingdom was on her side and at her disposal, while the Committee of Safety, by actual search, had discovered that there were but very few arms in Honolulu that were not in the service of the Government. In this state of things if the Queen could have dealt with the insurgents alone her course would have been plain and the result unmistakable. But the United States had allied itself with her enemies, had recognized them as the true Government of Hawaii, and had put her and her adherents in the position of opposition against lawful authority. She knew that she could not withstand the power of the United States, but she believed that she might safely trust to its justice. Accordingly, some hours after the recognition of the provisional government by the United States Minister, the palace, the barracks, and the police station, with all the military resources of the country, were delivered up by the Queen upon the representation made to her that her cause would thereafter be reviewed at Washington, and while protesting that she surrendered to the superior force of the United States, whose Minister had caused United States troops to be landed at Honolulu and declared that he would support the provisional government, and that she yielded her authority to prevent collision of armed forces and loss of life and only until such time as the United States, upon the facts being presented to it, should undo the action of its representative and reinstate her in the authority she claimed as the constitutional sovereign of the Hawaiian Islands (p. 453).”

The investigation concluded that the United States unlawfully intervened in the internal affairs of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and that its diplomat and troops were directly responsible for the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian government. Secretary of State Walter Gresham recommended to President Cleveland that the Hawaiian government must be restored and compensation provided. This prompted executive mediation between U.S. diplomat Albert Willis and Queen Lili‘uokalani in Honolulu to settle the dispute and by exchange of notes an executive agreement, called the “Agreement of Restoration,” was concluded whereby the President committed to the restoration of the Hawaiian government and the Queen, thereafter, to grant amnesty to the insurgents.

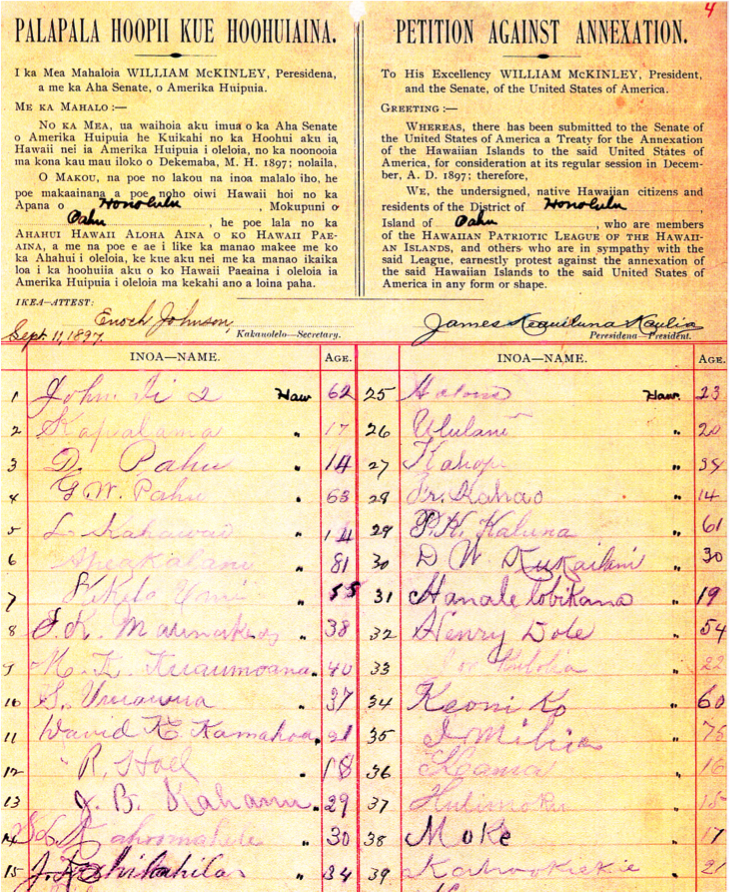

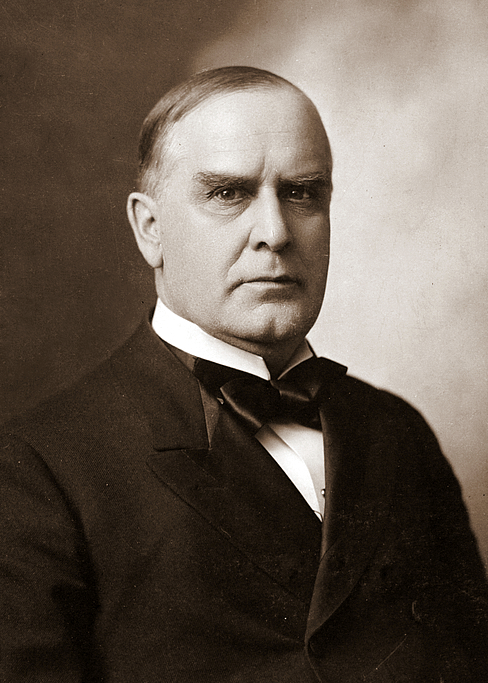

The President, however, did not carry out the international agreements because of political wrangling in the Congress, and the insurgents renamed themselves the Republic of Hawai‘i. President Cleveland’s successor, William McKinley, after failing to acquire Hawai‘i by a treaty of cession, signed a Congressional joint resolution of annexation into United States law on July 7, 1898, and unilaterally seized the Hawaiian Islands during the Spanish-American War on August 12, 1898, which began an illegal and prolonged occupation.

The President, however, did not carry out the international agreements because of political wrangling in the Congress, and the insurgents renamed themselves the Republic of Hawai‘i. President Cleveland’s successor, William McKinley, after failing to acquire Hawai‘i by a treaty of cession, signed a Congressional joint resolution of annexation into United States law on July 7, 1898, and unilaterally seized the Hawaiian Islands during the Spanish-American War on August 12, 1898, which began an illegal and prolonged occupation.

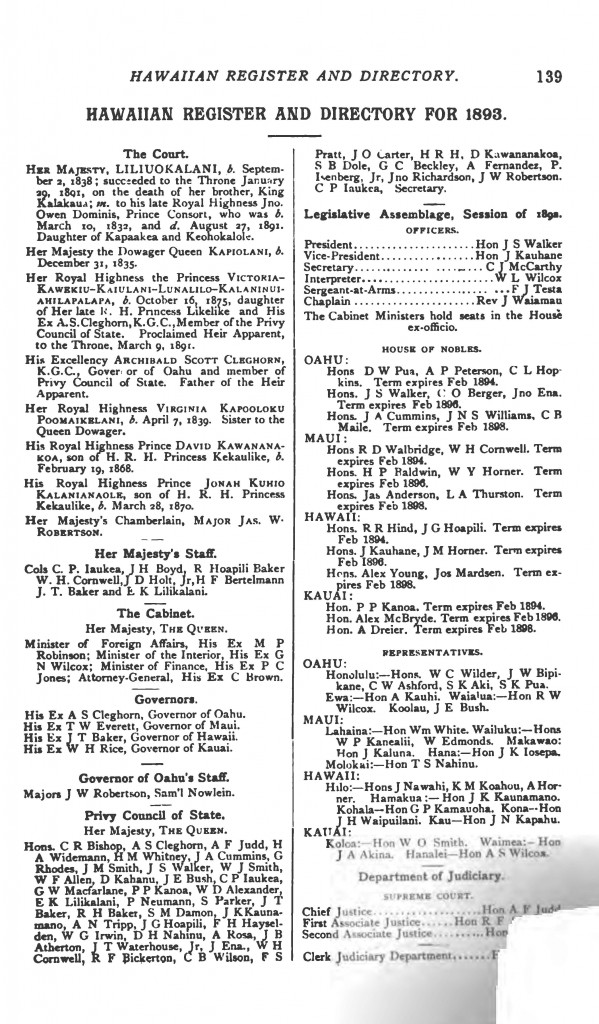

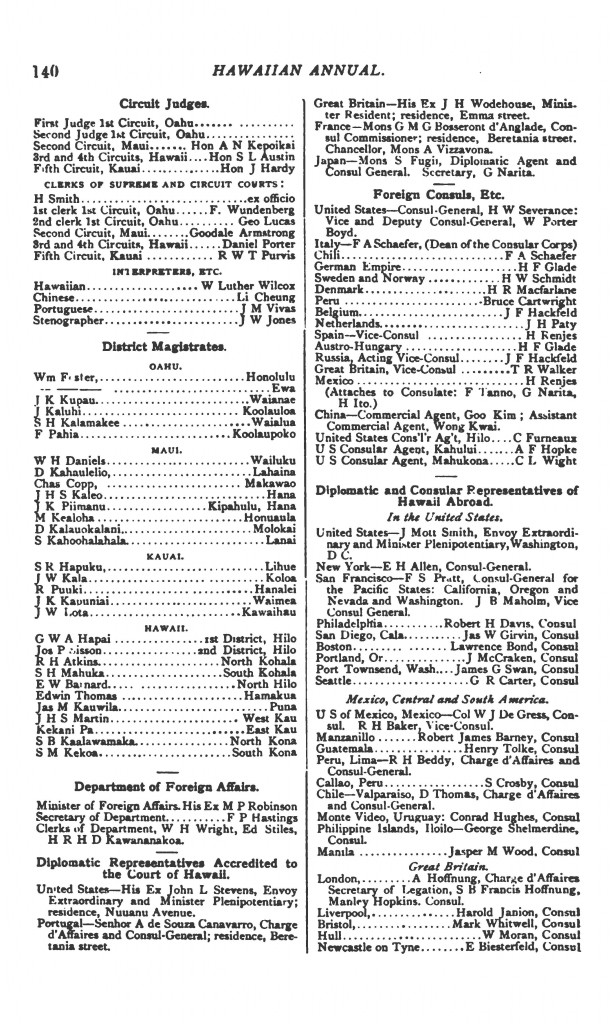

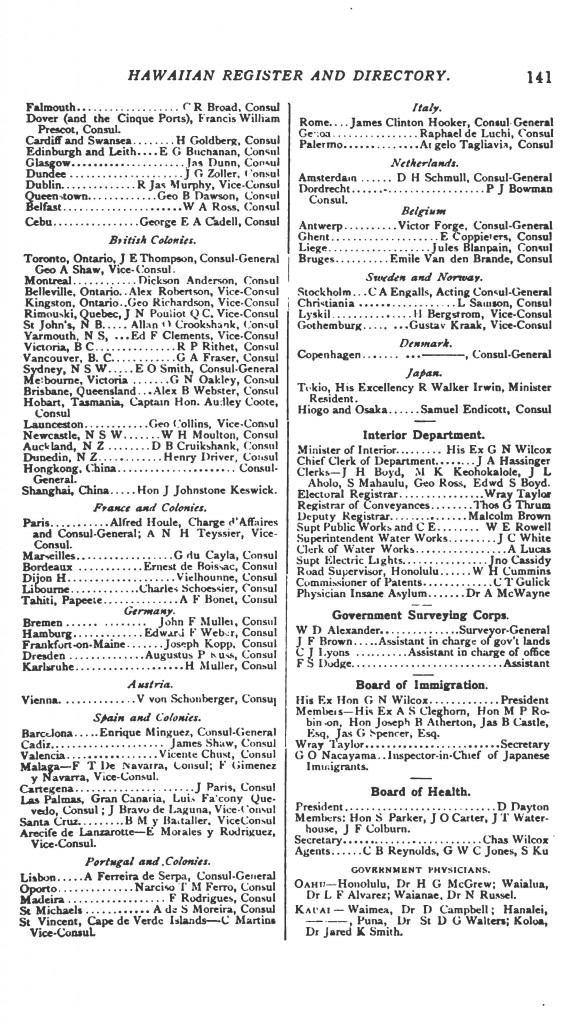

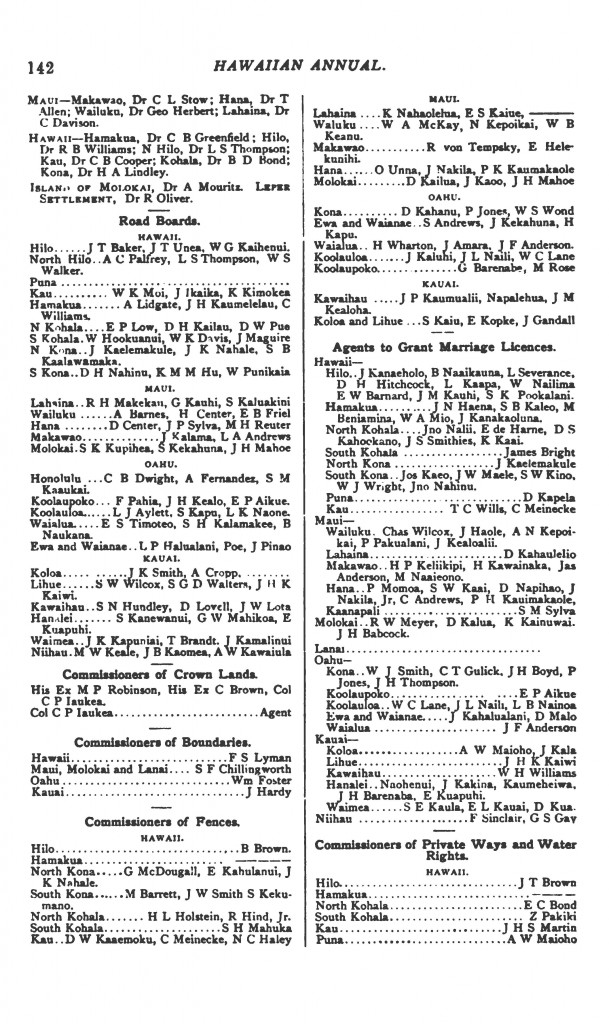

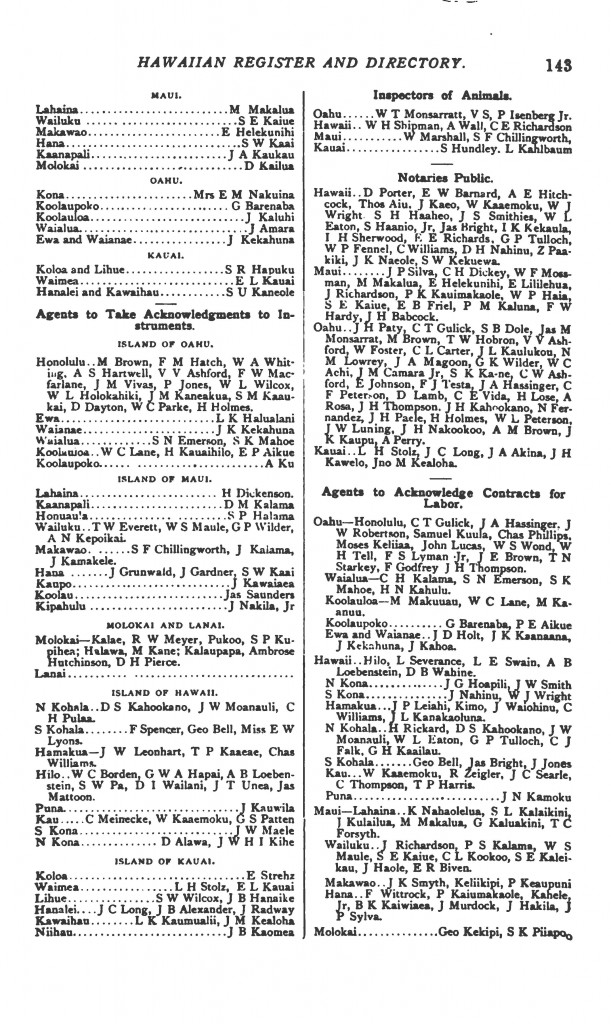

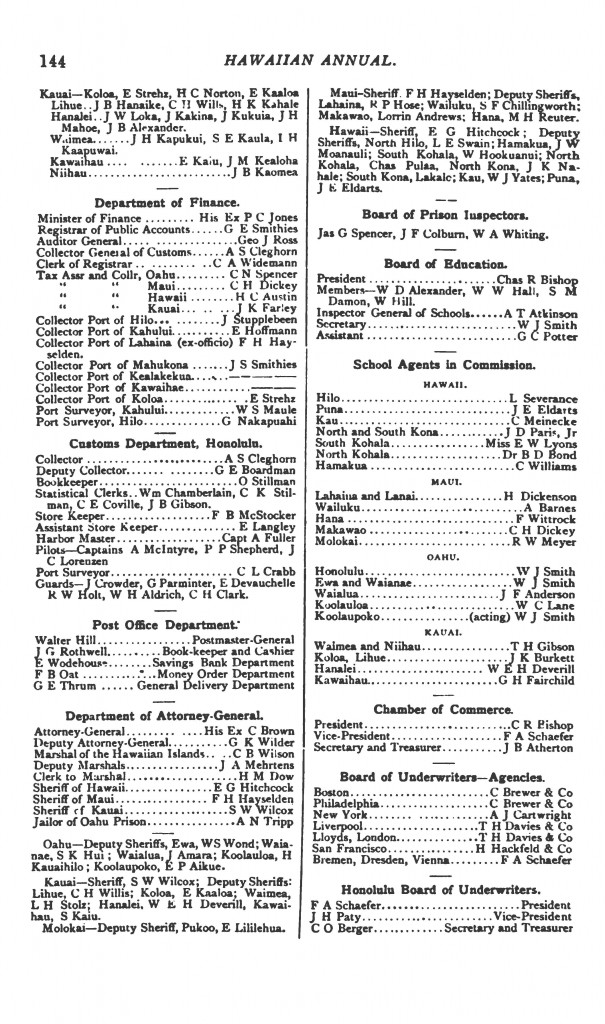

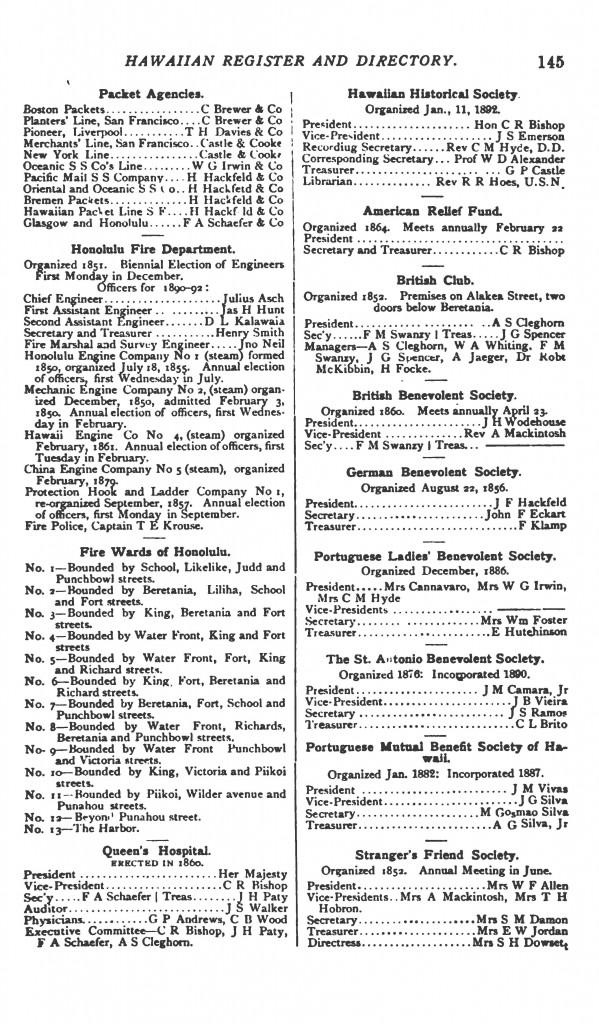

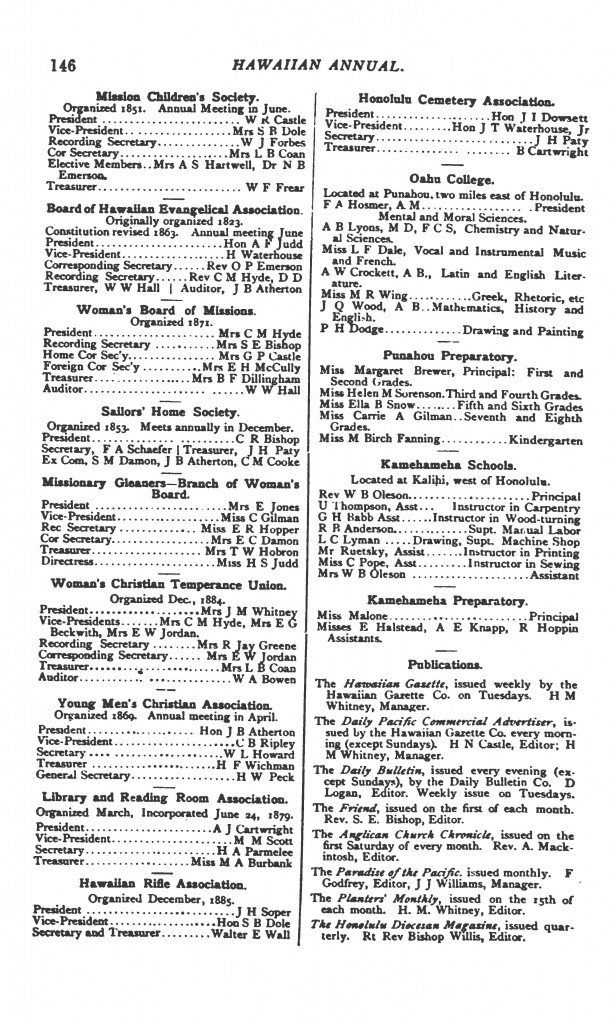

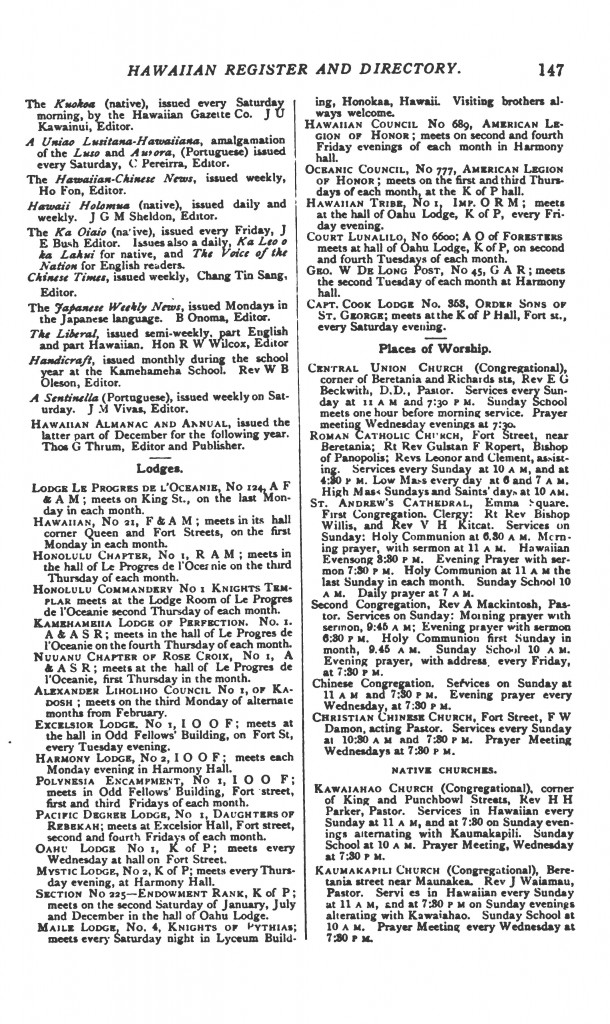

The Hawaiian Kingdom had completely adopted the separation of powers doctrine since 1864 and the government separated into three branches: executive, legislative and judicial. Here is what the government would have looked like if restoration took place according to the executive agreements, as provided by Thrum’s Hawaiian Annual for the year 1893.

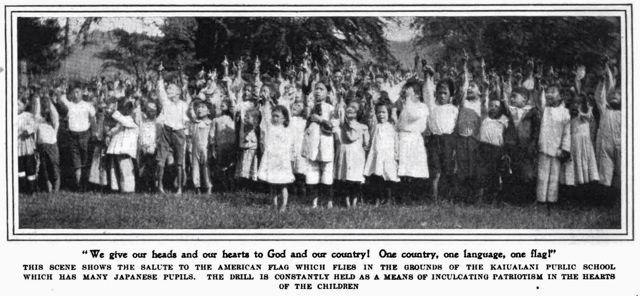

In 1900, President McKinley signed into United States law An Act To provide a government for the Territory of Hawai‘i, and transformed the so-called Republic of Hawai‘i into the Territory of Hawai‘i. After which the United States intentionally sought to “Americanize” the inhabitants of the Hawaiian Kingdom politically, culturally, socially, and economically. To accomplish this, a plan was instituted in 1906 by the Territorial government, titled “Program for Patriotic Exercises in the Public Schools, Adopted by the Department of Public Instruction,” whose purpose was to denationalize the children of the Hawaiian Islands through the public schools on a massive scale.

Nearly 50 years later where denationalization was nearly complete, steps were taken to transform the government of the Territory of Hawai‘i into the State of Hawai‘i. President Eisenhower signed into United States law An Act To provide for the admission of the State of Hawai‘i into the Union on March 18, 1959. These laws, which have no effect beyond United States territory, stand in direct violation of treaties between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States, the 1907 Hague Convention, IV, and the Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, IV.

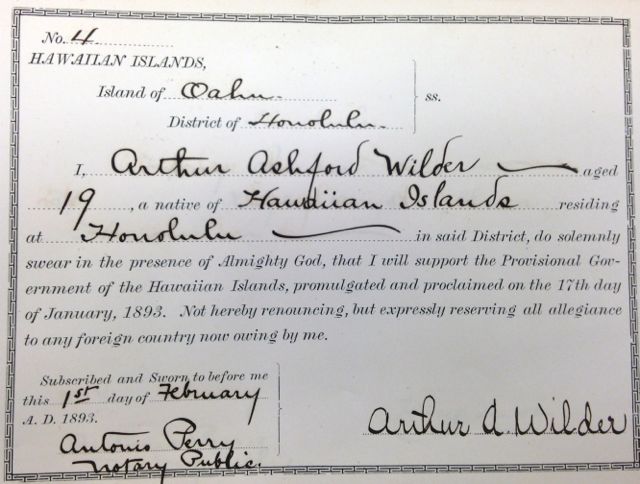

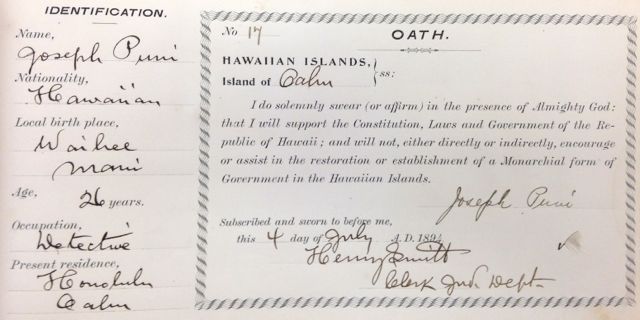

For the United States to have secured such a stronghold in the Hawaiian Islands as a governing body in a relatively short span of time was dependent upon the seizure of an already existing governmental infrastructure. The way in which thirteen insurgents calling themselves the Committee of Safety could take over the entire Hawaiian government on January 17, 1893, was by merely replacing the Queen as the chief executive and forcing everyone in the executive and judicial branches of government to sign oaths of allegiance while the U.S. troops provided oversight through intimidation and firepower. And when the U.S. troops were ordered to leave Hawai‘i on April 1, 1893, mercenaries replaced them until 1898 when U.S. troops returned to the islands.

A common misunderstanding is that the United States created the governmental infrastructure we have today through Congressional legislation such as the 1900 Organic Act that created the Territory of Hawai‘i, and the 1959 Admission Act that created the State of Hawai‘i. This is false. All that took place was the change in names and a few added agencies. The government of the State of Hawai‘i was formerly known as the government of the Territory of Hawai‘i. The government of the Territory of Hawai‘i was formerly known as the Republic of Hawai‘i. The government of the Republic of Hawai‘i was formerly known as the provisional government. And the government of the provisional government was formerly known as the Hawaiian Kingdom. The governmental infrastructure we see today was already in place in 1893.

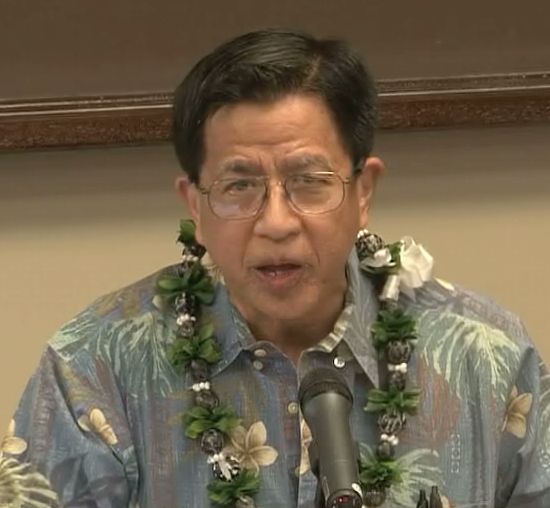

In a presentation at the University of Hawai‘i Richardson School of Law on April 17, 2014, senior Law Professor Williamson Chang stated, “The power of the United States, over the Hawaiian islands, and the jurisdiction of the United States in the State of Hawai‘i, by its own admissions, by its own laws, doesn’t exist. And so that means that ever since the 1898 annexation of Hawai‘i, by a Joint Resolution, they say, we have been living a myth.” “A joint resolution, as an act of Congress, cannot acquire another country,” he said. “If Congress cannot, by Joint Resolution in 1898, acquire Hawai‘i unilaterally, it cannot do so in 1959,” Chang said.

In a presentation at the University of Hawai‘i Richardson School of Law on April 17, 2014, senior Law Professor Williamson Chang stated, “The power of the United States, over the Hawaiian islands, and the jurisdiction of the United States in the State of Hawai‘i, by its own admissions, by its own laws, doesn’t exist. And so that means that ever since the 1898 annexation of Hawai‘i, by a Joint Resolution, they say, we have been living a myth.” “A joint resolution, as an act of Congress, cannot acquire another country,” he said. “If Congress cannot, by Joint Resolution in 1898, acquire Hawai‘i unilaterally, it cannot do so in 1959,” Chang said.

Because the United States Congress has no authority beyond the territory of the United States, the State of Hawai‘i cannot claim that it is a government duly authorized under a Congressional Act to govern the Hawaiian Islands. And as a direct successor of an insurgency that was unlawfully installed by the United States diplomat and troops on January 17, 1893, it too is neither a government de facto nor de jure. This means that actions that were understood to be governance are now interpreted as actions taken by individuals pretending to be a government. The law of occupation interprets these actions as war crimes: e.g. taxation is now interpreted as the crime of pillaging and theft; civil and criminal trials done by a court not properly constituted is now interpreted as the crime of depriving a person of a fair and regular trial; and to pursue federal recognition of Native Hawaiians as a tribe is interpreted as the crime of denationalization.

With this backdrop, Professor Chang warned the audience at the Law School, “I’m going to make one big point. …Its like a hand grenade, I’m going to give you the pin to the hand grenade, you pull the pin and everything blows up. So don’t pull the pin.”

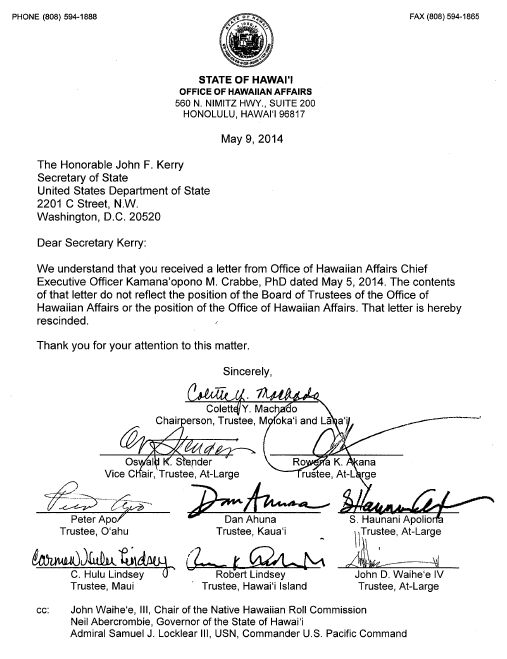

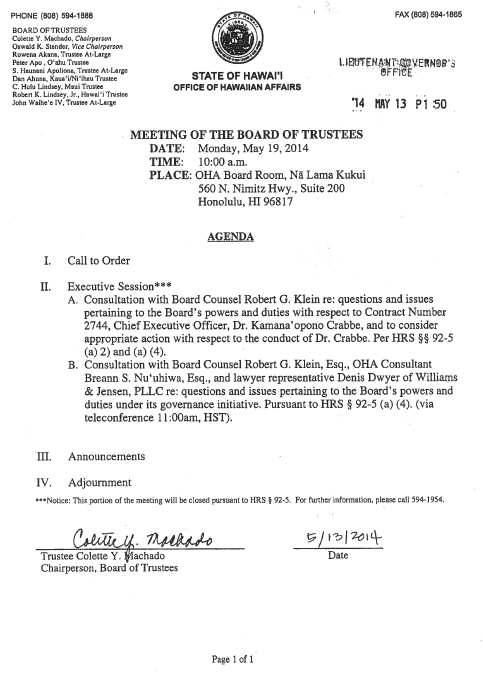

The only way for the State of Hawai‘i to remedy this situation is to begin to comply with the laws of occupation, and by the doctrine of necessity, begin to act as a United States military government administering the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the laws of occupation. This is a very complex situation and it should not be taken lightly. Dr. Keanu Sai was retained by the Office of Hawaiian Affairs CEO Dr. Kamana‘opono Crabbe to draft a memorandum and analysis of public international law and its effect on OHA and to provide recommendations in light of the alleged violations of international law and alleged war crimes. Dr. Crabbe provided all nine trustees a copy of Dr. Sai’s memorandum last week Friday.

Anecdotally—in 1893, the Hawaiian Porsche was carjacked by the United States and painted red, white and blue. Although we have not been driving the Porsche for the past 121 years and were brainwashed to believe it was not a Hawaiian car, it doesn’t mean the Porsche belongs to the United States. The fact that this history, which only spans two generations, is not common knowledge is the evidence of denationalization and the violation of Hawaiian sovereignty.