Donovan Preza’s Fourth of Four Presentations United Church of Christ – Kuleana Lands

Reply

Speaking to Pacific island leaders, Reuters reported President Joe Biden said “Russia’s assault on Ukraine in pursuit of imperial ambitions is a flagrant, flagrant violation of the UN Charter, and the basic principles of sovereignty and territorial integrity.” The world should know that this is a classic case of the pot calling the kettle black, which is an idiom that means a person should not criticize another person for a fault they themselves have.

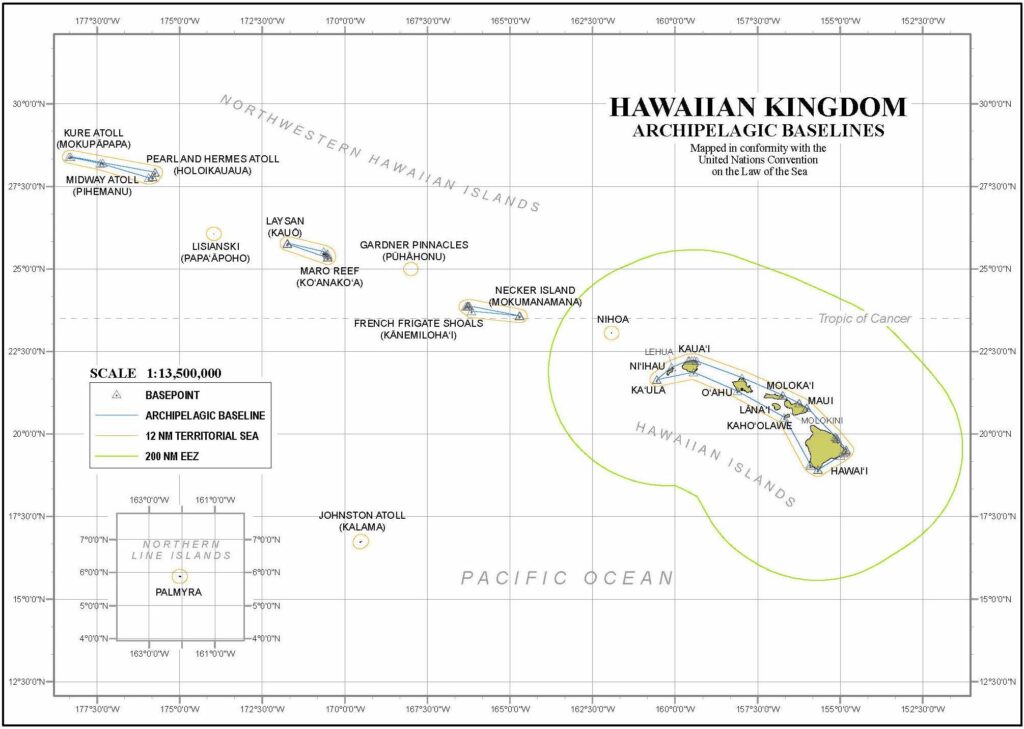

Like Ukraine, the Hawaiian Kingdom was an internationally recognized independent State. Where Ukraine got its independence in 1991 after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Hawaiian Kingdom achieved its independence when Great Britain and France jointly proclaimed that both countries recognized the Hawaiian Islands as an independent State in 1843. The United States explicitly acknowledged Hawaiian independence on July 6, 1844.

One of the fundamental principles of international law is the sovereignty, which is supreme authority, and territorial integrity of an independent State. Independent States have exclusive authority over its territory that is subject to its own laws and not the laws of any other State.

In 1997, a treaty of friendship, cooperation, and partnership between Ukraine and the Russian Federation was signed that came into force on April 1, 2000. Article 2 of the treaty states that “the High Contracting Parties shall respect each other’s territorial integrity and reaffirm the inviolability of the borders existing between them.”

In 1849, a treaty of friendship, commerce and navigation between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States was signed that came into force on November 9, 1850. Territorial integrity is acknowledged in article 8 of the treaty that states “each of the two contracting parties engages that the citizens or subjects of the other residing in their respective states, shall enjoy their property and personal security, or the subjects or citizens of the most favored nation, but subject always to the laws and statutes of the two countries respectively.”

Both Ukraine and the Hawaiian Kingdom established diplomatic relations with their treaty partners. While Ukraine maintained an embassy in Moscow, and Russia maintained an embassy in Kiev, the Hawaiian Kingdom maintained an embassy in Washington, D.C., and the United States maintained an embassy in Honolulu.

Like Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24, 2022, the United States invaded the Hawaiian Kingdom on January 16, 1893. In a presidential investigation, U.S. President Grover Cleveland acknowledged that the U.S. “military demonstration upon the soil of Honolulu was itself an act of war,” which led to the overthrow of the Hawaiian government the following day. The purpose of the invasion and overthrow was to secure Pearl Harbor as a naval base of operations to protect the west coast of the United States from invasion by Japan. The Russian invasion of Ukraine was to buffer an invasion by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization or NATO, which the United States is a member of.

On January 31, 1893, U.S. Captain Alfred Mahan from the Naval War College wrote a letter to the Editor of the New York Times where he advocated seizing the Hawaiian Islands. In his letter, Captain Mahan recognized the Hawaiian Islands, “with their geographical and military importance [to be] unrivaled by that of any other position in the North Pacific.” Mahan used the Hawaiian situation to bolster his argument of building a large naval fleet. He warned that a maritime power could well seize the Hawaiian Islands, and that the United States should take that first step. He wrote, “To hold [the Hawaiian Islands], whether in the supposed case or in war with a European state, implies a great extension of our naval power. Are we ready to undertake this?”

Although President Cleveland apologized for the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government and entered into a treaty with Queen Lili‘uokalani on December 18, 1893, to restore her to the Hawaiian throne as a constitutional executive monarch, he was prevented from doing so because of the war hawks in the Congress that wanted Pearl Harbor. This consequently placed the Hawaiian Islands in civil unrest under the control of insurgents that received support from Americans in the United States. They were pretending to be a government by calling themselves the provisional government. The reason for the pretending is because President Cleveland’s investigation already concluded “that the provisional government owes its existence to an armed invasion by the United States.” In other words, the insurgents were a puppet of the U.S.

Five years would lapse, and the Cleveland administration was replaced by President William McKinley. U.S. Secretary of the Navy John Young was an advocate for annexing the Hawaiian Islands. Secretary Long was influenced by Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt, who would later become President in 1901. On May 3, 1897, Roosevelt wrote a letter to Captain Mahan. He stated, “I need not tell you that as regards Hawaii I take your views absolutely, as indeed I do on foreign policy generally. If I had my way we would annex those islands tomorrow.” Roosevelt also stated that Cleveland’s handling of the Hawaiian situation was “a colossal crime, and we should be guilty of aiding him after the fact if we do not reverse what he did.” Roosevelt also assured Mahan, that “Secretary Long shares our views. He believes we should take the islands, and I have just been preparing some memoranda for him to use at the Cabinet meeting tomorrow.”

The opportunity for the United States to seize the Hawaiian Islands occurred at the height of the Spanish-American War. On July 6, 1898, the war hawks in the Congress passed a joint resolution declaring that the Hawaiian Islands had been annexed and President McKinley signed it into law the following day.

The opportunity for Russia to seize a portion of Ukrainian territory came after sham referendums where the people of the regions of Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia voted to be Russian and not remain Ukrainian. On September 30, 2022, Reuters reported that “Russian President Vladimir Putin announced Russia had ‘four new regions’ in a speech in the Kremliin on Friday in which he outlined Russia’s annexation of four Ukrainian regions that Moscow’s forces have partially seized during a seven-month conflict with Ukraine.”

Despite the American annexation of the Hawaiian Islands and the Russian annexation of the four Ukrainian regions, they remain illegal under international law. Because it is illegal it did not alter the territorial integrity of both the Hawaiian Kingdom and Ukraine as independent States. As Professor Malcolm Shaws wrote, “It is, however, clear today that the acquisition of territory by force alone is illegal under international law.” And according to The Handbook of Humanitarian Law in Armed Conflicts (1995):

The international law of belligerent occupation must therefore be understood as meaning that the occupying power is not sovereign, but exercises provisional and temporary control over foreign territory. The legal situation of the territory can be altered only through a peace treaty. International law does not permit annexation of territory of another State.

The return of unlawfully annexed territory occurs when there are changes in the physical power of the usurping State. Since the usurping State has no lawful authority over annexed territory, its possession is based purely on power and not law. Similarly, the abductor of a kidnapped child, being an act prohibited by law, does not become the parent of the child by force despite the length of the kidnapping. And when the child is eventually rescued and the power of the abductor eliminated and taken into custody, the child can then return to the family.

Unlike Ukraine, there was no Reuters news agency in the 1890s informing the world of the illegal activities of the United States against the Hawaiian Kingdom and the illegal annexation of the Hawaiian Islands for military purposes during the Spanish-American War. While there is a difference in time, the Russian actions bear a striking resemblance to the United States actions in seizing the entire territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom. While both the American and Russian actions are unlawful, the Hawaiian Kingdom, like Ukraine, remain independent States under international law together with their territorial integrity intact despite the unlawful annexations.

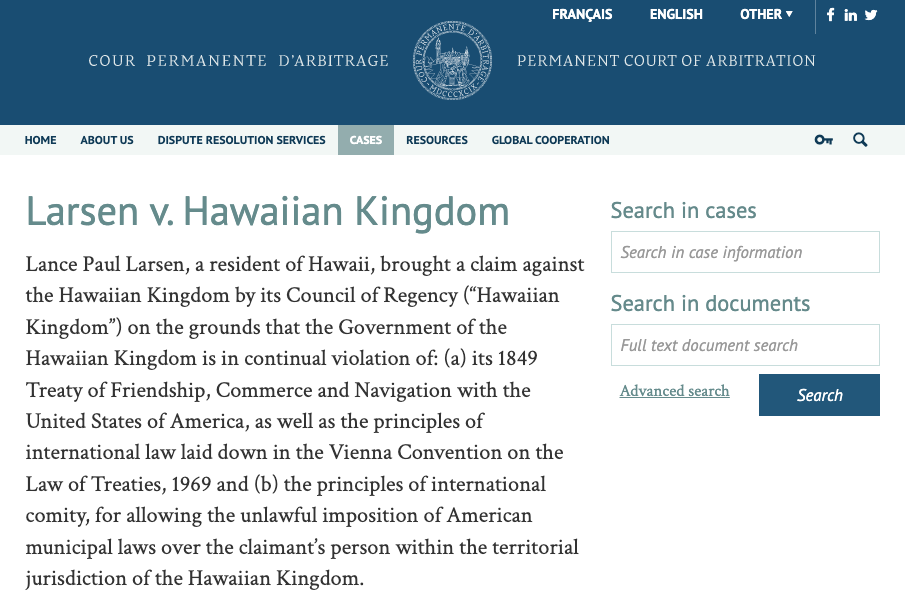

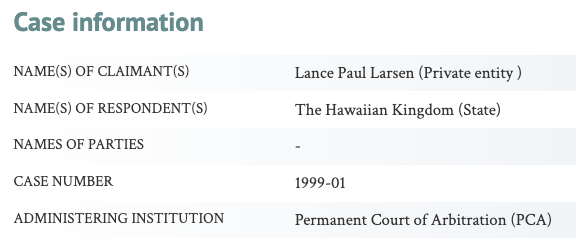

In the case of the Hawaiian Kingdom, the Permanent Court of Arbitration, in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, acknowledged the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a “State” under international law in 1999, which includes its territorial integrity. In the case of Ukraine, everyone in the world already knows that Ukraine is a “State” under international law.

This is a classic case of the American pot calling the Russian kettle black.

For more information on the belligerent occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom by the United States and the unilateral annexation of Hawaiian territory, read Dr. Keanu Sai’s law article Backstory – Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom at the Permanent Court of Arbitration (1999-2001).

There is a common misunderstanding among the world that Hawai‘i is the 50th state of the American union. The historical and legal revealing of evidence that Hawai‘i is not the 50th state, but rather the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State, has shattered this belief for those who have come to know. To better understand the why, here is the history of the formation of the 49 States of the American union that many don’t know.

All 49 states of the American union were acquired through international law because these territories were formerly the territories of other independent States. The first 13 states, which were formerly British Crown colonies, were acquired from the British Crown by the 1783 Treaty of Paris that brought the revolution to an end. Article I provided, “His Brittanic Majesty acknowledges the said United States, viz., New Hampshire, Massachusetts Bay, Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia, to be free sovereign and Independent States; that he treats with them as such, and for himself his Heirs & Successors, relinquishes all claims to the Government, Propriety, and Territorial Rights of the same and every Part thereof.”

In 1789, as a result of the federalist movement, these 13 sovereign and independent States collectively gave their independence to the federal government, which came to be known as the American union. These states held what was referred to as residual sovereignty but no longer retained independence. The instrument that formed this union was the federal constitution. Prior to this consolidation, these independent States were in a loose union called a confederacy according to the terms of the 1777 Articles of Confederation.

The other states of the union were formed out of territories acquired by the federal government through international treaties, with the exception of Hawai‘i, which was unilaterally annexed by a congressional statute in 1898.

There is also a common misunderstanding that the State of Texas came about as a result of a joint resolution of Congress in 1845. The truth of the matter is that this congressional action is what sparked the Mexican-American war in 1846. The State of Texas was on Mexican territory and not United States territory. In the 1848 Peace Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that ended the war, the new border between the two Republics began from the Gulf of Mexico along the Rio Grande river, which is the southern border of the State of Texas, then by a surveyed boundary line that runs along the southern borders of what are now States of New Mexico, Arizona and California. Article V of the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo states:

The boundary line between the two Republics shall commence in the Gulf of Mexico, three leagues from land, opposite the mouth of the Rio Grande, otherwise called Rio Bravo del Norte, or Opposite the mouth of its deepest branch, if it should have more than one branch emptying directly into the sea; from thence up the middle of that river, following the deepest channel, where it has more than one, to the point where it strikes the southern boundary of New Mexico; thence, westwardly, along the whole southern boundary of New Mexico (which runs north of the town called Paso) to its western termination; thence, northward, along the western line of New Mexico, until it intersects the first branch of the river Gila; (or if it should not intersect any branch of that river, then to the point on the said line nearest to such branch, and thence in a direct line to the same); thence down the middle of the said branch and of the said river, until it empties into the Rio Colorado; thence across the Rio Colorado, following the division line between Upper and Lower California, to the Pacific Ocean.

If Texas was annexed in 1845, then the boundary would not have begun from the Gulf of Mexico, but rather from the surveyed boundary line that would have begun from the mid-southern border of what is now the State of New Mexico, which is adjacent to the city of El Paso, Texas. From El Paso, the Rio Grande river goes north into the State of New Mexico.

In 1988, the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) published a legal opinion regarding the annexation of Hawai‘i. The OLC’s memorandum opinion was written for the Legal Advisor for the Department of State regarding legal issues raised by the proposed Presidential proclamation to extend the territorial sea from a three-mile limit to twelve miles. The OLC concluded that only the President and not the Congress possesses “the constitutional authority to assert either sovereignty over an extended territorial sea or jurisdiction over it under international law on behalf of the United States.” As Justice Marshall stated, “[t]he President is the sole organ of the nation in its external relations, and its sole representative with foreign nations,” and not the Congress.

The OLC also stated, “we doubt that Congress has constitutional authority to assert either sovereignty over an extended territorial sea or jurisdiction over it under international law on behalf of the United States.” The OLC then concluded that it is “unclear which constitutional power Congress exercised when it acquired Hawaii by joint resolution. Accordingly, it is doubtful that the acquisition of Hawaii can serve as an appropriate precedent for a congressional assertion of sovereignty over an extended territorial sea.”

That territorial sea referred to by the OLC was to be extended from three to twelve miles under the 1982 United Nations Law of the Sea Convention. In other words, the Congress could not extend the territorial sea an additional nine miles by statute because its authority was limited up to the three-mile limit. Furthermore, the United States Supreme Court, in The Apollon, concluded that the “laws of no nation can justly extend beyond its own territories.”

Arriving at this conclusion, the OLC cited constitutional scholar Professor Willoughby, “The constitutionality of the annexation of Hawaii, by a simple legislative act, was strenuously contested at the time both in Congress and by the press. The right to annex by treaty was not denied, but it was denied that this might be done by a simple legislative act. …Only by means of treaties, it was asserted, can the relations between States be governed, for a legislative act is necessarily without extraterritorial force—confined in its operation to the territory of the State by whose legislature enacted it.” Professor Willoughby also stated, “The incorporation of one sovereign State, such as was Hawaii prior to annexation, in the territory of another, is…essentially a matter falling within the domain of international relations, and, therefore, beyond the reach of legislative acts.”

Under international law, what was illegally overthrown on January 17, 1893, was the Hawaiian Kingdom government and not the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State. International law distinguishes between the independent State and its government. For one State to acquire the territory of another State there needs to be a treaty like the United States treaty of cessions with Great Britain, France, Mexico, Russia and Spain. When the United States unilaterally annexed Hawai‘i by a congressional joint resolution in 1898, the act was no different than Iraq unilaterally annexing Kuwait in 1990 during the First Gulf War, or Nazi Germany unilaterally annexing Luxembourg during the Second World War. Both were illegal under international law and so is the annexation of Hawai‘i.

In 1997, the Hawaiian government was constitutionally restored by a Council of Regency that serves in the absence of the Monarch. Two years later, both the Hawaiian Kingdom, as a State, and the Council of Regency, as its government, was acknowledged in 1999 by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague, Netherlands, in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom.

The phrase “come home to roost” means to have unfavorable repercussions for actions taken in the past, example: “You ought to have known that your lies would come home to roost in the end”—Charles West, Stage Fright. Proceedings in Hawaiian Kingdom v. Biden is drawing attention to the United States and State of Hawai‘i actions of the past.

When federal court proceedings for Hawaiian Kingdom v. Biden were initiated on May 20, 2021, the court’s status as an Article III Court was the primary issue. Article III refers to the judicial branch of the U.S. Constitution. The U.S. Constitution does not have any legal enforcement outside the United States, and, therefore, federal courts can only operate within U.S. territory. Because the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist as an independent, but occupied, State, the federal court in Honolulu has no legal basis.

However, under U.S. law, a federal court can operate outside of the United States if the foreign territory is being belligerently occupied by the U.S. In this case, the authority would come under Article II of the U.S. Constitution, which is the executive branch of government headed by the President. As the President is the commander-in-chief of the military that is occupying foreign territory, an Article II Occupation Court can be established to administer the laws of the occupied country and international humanitarian law—laws of war, which includes the law of occupation. The 1907 Hague Regulations and the 1949 Fourth Geneva Convention regulate foreign occupations.

After the Nazi government was overthrown in 1945, the United States, along with France, Great Britain and the Soviet Union began to occupy the German State. In the United States sector of occupation, an Article II Occupation Court was established to administer German law and international humanitarian law.

When the proceedings began, the focus was on getting the federal court to transform from an Article III Court to an Article II Occupation Court. The International Association of Democratic Lawyers, the National Lawyers Guild and the Water Protector Legal Collective, co-authored an amicus curiae brief that would assist the federal court to understand what an Article II Occupation Court is and why the federal court should transform from an Article III Court. Their request to file the brief was approved by Magistrate Judge Rom Trader on September 30, 2021, and the amicus brief was filed with the court on October 6, 2021.

The focus in these proceedings have recently shifted from having the federal court transform to an Article II Occupation Court to a preliminary issue called the Lorenzo principle. The Lorenzo principle is State of Hawai‘i common law or judge made law that centers on whether the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist as a State despite the overthrow of its government by the United States on January 17, 1893.

The case that the Lorenzo principle is based on is State of Hawai‘i v. Lorenzo that came before the Hawai‘i Intermediate Court of Appeals (ICA) in 1994. The principle is evidence based and requires defendants in cases that have come before courts of the State of Hawai‘i since 1994 to provide evidence that the kingdom continues to exist and to not just argue that it exists. This was the case in State of Hawai‘i v. Araujo, where the ICA stated:

Because Araujo has not, either below or on appeal, “‘presented any factual or legal basis for concluding that the Kingdom exists as a state in accordance with recognized attributes of a state’s sovereign nature,’” (citing Lorenzo, 77 Hawai‘i at 221, 883 P.2d at 643), his point of error on appeal must fail.

The Lorenzo principle also separates the Native Hawaiian sovereignty movement and nation building from the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State. The Hawai‘i Supreme Court, in State of Hawai‘i v. Armitage, not only clarified the evidentiary burden but also discerned between a new Native Hawaiian nation brought about through nation-building, and the Hawaiian Kingdom that existed as a State in the nineteenth century. The Hawai‘i Supreme Court explained:

Petitioners’ theory of nation-building as a fundamental right under the ICA’s decision in Lorenzo does not appear viable. Lorenzo held that, for jurisdictional purposes, should a defendant demonstrate a factual or legal basis that the [Hawaiian Kingdom] “exists as a state in accordance with recognized attributes of a state’s sovereign nature[,]” and that he or she is a citizen of that sovereign state, a defendant may be able to argue that the courts of the State of Hawai‘i lack jurisdiction over him or her. Thus, Lorenzo does not recognize a fundamental right to build a sovereign Hawaiian nation.

In these proceedings, the Hawaiian Kingdom has clearly provided irrefutable evidence that the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist as a State, especially when the Permanent Court of Arbitration acknowledged its continued existence in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom. In this type of a situation, the Lorenzo principle, when applying international law, requires the party opposing the continued existence of the kingdom to provide evidence, whether factual or legal, that the kingdom does not continue to exist.

In other words, if any of the defendants in these proceedings wants the court to dismiss this case, they are required to provide evidence that the kingdom no longer exists in accordance with the standard of evidence that the Lorenzo principle established. Clear evidence that the Hawaiian Kingdom would no longer exist as a State is a treaty of cession where the Hawaiian Kingdom incorporated itself into the United States. There is no such treaty.

On June 19, 2022, the Clerk of the federal court entered defaults for the State of Hawai‘i, Governor David Ige, Securities Commissioner Ty Nohara, and Director of the Department of Taxation Isaac Choy for failing to answer the amended complaint filed on August 11, 2021.

In an attempt to have the federal court set aside the defaults, the State of Hawai‘i Attorney General’s office, on behalf of the State of Hawai‘i, Governor Ige, Securities Commissioner Nohara and the Director of Taxation Choy, filed a motion to set aside defaults on August 12, 2022.

In its memorandum in support of its motion, the State of Hawai‘i Defendants stated that once the defaults are set aside they intend to file a motion to dismiss because since the case presents a political question, the federal court has no jurisdiction over the issue and must dismiss the case. It is the same argument that the Federal Defendants are making. Both claim that the political branches of government, which are the President and Congress, no longer recognizes the Hawaiian Kingdom, and until they do federal courts cannot have jurisdiction because it is a question for the political branches to decide first.

What undercuts this argument is the United States own Restatement (Third) Foreign Relations Law, §202, comment g, which clearly states, “The duty to treat a qualified entity as a state also implies that so long as the entity continues to meet those qualifications its statehood may not be ‘derecognized.’ If the entity ceases to meet those requirements, it ceases to be a state and derecognition is not necessary.”

This is merely reiterating the rule of customary international law. According to Professor Oppenheim, once recognition of a State is granted, it “is incapable of withdrawal” by the recognizing State. And Professor Schwarzenberger explains that “recognition estops the State which has recognized the title from contesting its validity at any future time.”

The United States cannot simply de-recognize an independent State because it is politically convenient to do so. If it were such a case and allowable under international law, which it is not, then why wouldn’t the United States de-recognize its adversaries like China, Russia and North Korea.

Another problem that both the Federal and the State of Hawai‘i Defendants have is the Lorenzo principle that binds all State of Hawai‘i courts and the federal court in Honolulu. The Lorenzo principle states that the question as to whether the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist as a State is a “legal question” and not a “political question.”

A legal question is where a court makes a decision based on factual or legal evidence, and in order for the court to decide that legal question it must have jurisdiction to do so. A political question prevents the court from deciding because it does not have jurisdiction in the first place. This is an absurd argument and in all 53 cases that applied the Lorenzo principle by the Hawai‘i Supreme Court and the Intermediate Court of Appeals, and the 17 case that applied the Lorenzo principle in the federal court in Honolulu and by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, not one argued the political question doctrine.

Here when the evidence is abundantly clear that the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist as a State, the Federal and State of Hawai‘i Defendants scream POLITICAL QUESTION. This baseless argument really speaks volumes as to the strength of the evidence in this case that the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist as a State.

Yesterday, the Hawaiian Kingdom filed its Opposition and requested that Magistrate Judge Trader schedule an evidentiary hearing so that the State of Hawai‘i Defendants can prove with evidence that the Hawaiian Kingdom no longer exists as a State according to the evidentiary standard set by the Lorenzo principle. The Hawaiian Kingdom also filed a request for the Magistrate Judge to take Judicial Notice of evidence that the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist as a State.

In its Opposition, the Hawaiian Kingdom concluded with:

For these reasons, the Plaintiff respectfully requests that the Court schedule an evidentiary hearing in accordance with the Lorenzo principle for the State Defendants to provide rebuttable evidence, whether factual or legal, that the Hawaiian Kingdom ceases to exist as a State in light of the evidence and law in the instant motion. If the State Defendants are unable to proffer rebuttable evidence, the Plaintiff respectfully requests that this Court transform into an Article II Occupation Court in order for the Court to possess subject matter and personal jurisdiction to consider the State Defendants’ motion to set aside defaults. The transformation to an Article II Occupation Court is fully elucidated in the brief of amici curiae the International Association of Democratic Lawyers, the National Lawyers Guild, and the Water Protectors Legal Collective [ECF 96]. When the Court has jurisdiction, the Plaintiff will not oppose the State Defendants motion to set aside defaults.

Should the State Defendants proffer evidence of a treaty of cession that the Hawaiian Kingdom ceded its territory and sovereignty to the United States, whereby the Hawaiian State ceased to exist under international law, the Plaintiff will withdraw its amended complaint for declaratory and injunctive relief [ECF 55] and bring these proceedings to a close.

Plaintiff’s request for an evidentiary hearing and judicial notice pursuant to the Lorenzo principle is in compliance with §34 of the Federal Judiciary Act of September 24, 1789, 28 U.S.C. §1652, which provides, “The laws of the several states, except where the Constitution or treaties of the United States or Acts of Congress otherwise require or provide, shall be regarded as rules of decision in civil actions in the courts of the United States, in cases where they apply.”

As the United States Supreme Court, in Erie R.R. v. Tompkins, stated, “federal courts are […] bound to follow decisions of the courts of the State in which the controversies arise.” This case is manifestly governed by Erie and the Lorenzo principle. It is not governed by Baker v. Carr as to the political question doctrine.

On August 15, 2022, Judge Leslie Kobayashi filed an Order denying the Hawaiian Kingdom’s request to allow the Ninth Circuit to review her previous Order dated July 28, 2022, denying the Hawaiian Kingdom’s motion to reconsider her decision. Federal rules allow a party to file a motion for reconsideration within 10 days of the Order. In her August 15 Order, she stated:

“Here, whether the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist as a sovereign and independent state is not a controlling question of law. ‘The Ninth Circuit, this court, and Hawaii state courts have rejected arguments asserting Hawaiian sovereignty.’ Although the resolution of whether the Hawaiian Kingdom exists as a sovereign and independent state could, theoretically, materially affect the outcome of litigation, the question presented does not rise to the level of an exceptional case warranting departure from the congressional directive to grant interlocutory appeals sparingly.”

The Hawaiian Kingdom does not agree with Judge Kobayashi that the Hawaiian Kingdom’s existence is not a controlling question of law that would bind the Court. On August 24, 2022, the Hawaiian Kingdom filed a motion for Judge Kobayashi to reconsider her decision on the grounds of judicial estoppel, and in accordance with the Lorenzo principle to schedule an evidentiary hearing in order to compel the Federal Defendants to prove that the Hawaiian Kingdom no longer exists as a State. According to the Ninth Circuit, in Rissetto v. Plumbers & Steamfitters Local 343, judicial estoppel prevents “a party from gaining an advantage by taking one position, and then seeking a second advantage by taking an incompatible position.”

In its recent filing, the Hawaiian Kingdom drew attention to the United States’ position in support of the Lorenzo principle in United States v. Goo in 2002 where it prevailed, and then in these proceedings regarding the Lorenzo principle they act as if it never existed. The Lorenzo principle stems from the Hawai‘i Intermediate Court of Appeals (ICA) case State of Hawai‘i v. Lorenzo that centered on the subject of whether the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State still exists.

This case not only placed the burden of proof that the Kingdom still exists on the defendant, but it also separated the Hawaiian Kingdom from the native Hawaiian sovereignty movement and nation building. In 2014, the Hawai‘i Supreme Court, in State of Hawai‘i v. Armitage, explained:

“Petitioners’ theory of nation-building as a fundamental right under the ICA’s decision in Lorenzo does not appear viable. Lorenzo held that, for jurisdictional purposes, should a defendant demonstrate a factual or legal basis that the [Hawaiian Kingdom] ‘exists as a state in accordance with recognized attributes of a state’s sovereign nature[,]’ and that he or she is a citizen of that sovereign state, a defendant may be able to argue that the courts of the State of Hawai‘i lack jurisdiction over him or her. Thus, Lorenzo does not recognize a fundamental right to build a sovereign Hawaiian nation.”

The ICA reiterated that a defendant has to provide evidence of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s existence as a State and not just say it exists. In State of Hawai‘i v. Araujo, the ICA stated:

Because Araujo has not, either below or on appeal, “‘presented any factual or legal basis for concluding that the Kingdom exists as a state in accordance with recognized attributes of a state’s sovereign nature,’” (citing Lorenzo, 77 Hawai‘i at 221, 883 P.2d at 643), his point of error on appeal must fail.

The Lorenzo court, however, also acknowledged that it may have misplaced the burden of proof and what needs to be proven. It stated, “although the court’s rationale is open to question in light of international law, the record indicates that the decision was correct because Lorenzo did not meet his burden of proving his defense of lack of jurisdiction.”

Because international law provides for the presumption of the continuity of the State despite the overthrow of its government by another State, it shifts the burden of proof and what is to be proven. According to Judge Crawford, there “is a presumption that the State continues to exist, with its rights and obligations despite a period in which there is no, or no effective, government.” Judge Crawford also stated that belligerent occupation “does not affect the continuity of the State, even where there exists no government claiming to represent the occupied State.”

In other words, under international law, it is presumed the Hawaiian Kingdom still exists as a State despited its government being militarily overthrown by the United States on January 17 1893. Addressing the presumption of the continuity of the German State after hostilities ceased in Europe during the Second World War, Professor Brownlie explains:

“Thus, after the defeat of Nazi Germany in the Second World War the four major Allied powers assumed supreme power in Germany. The legal competence of the German state [its independence and sovereignty] did not, however, disappear. What occurred is akin to legal representation or agency of necessity. The German state continued to exist, and, indeed, the legal basis of the occupation depended on its continued existence.”

“If one were to speak about a presumption of continuity,” explains Professor Craven, “one would suppose that an obligation would lie upon the party opposing that continuity to establish the facts substantiating its rebuttal. The continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom, in other words, may be refuted only by reference to a valid demonstration of legal title, or sovereignty, on the part of the United States, absent of which the presumption remains.” A “valid demonstration of legal title” would be an international treaty where the Hawaiian Kingdom ceded itself to the United States. No such treaty, except for the “Big Lie” that Hawai‘i is a part of the United States.

Up until now, the State of Hawai‘i courts and the federal court in Honolulu have been placing the burden on the defendants to prove the Kingdom still exists. Whether the burden is to prove the kingdom’s existence or to prove it doesn’t exist, it is a controlling law that binds the State of Hawai‘i courts.

The Lorenzo case had become a precedent case and was cited by the Hawai‘i Supreme Court in 8 cases, and by the ICA in 45 cases. The latest Hawai‘i Supreme Court’s citation of Lorenzo was in 2020 in State of Hawai‘i v. Malave. The most recent citation of Lorenzo by the ICA was in 2021 in Bank of N.Y. Mellon v. Cummings. Since 1994, Lorenzo had risen to precedent, and, therefore, is common law. Federal law mandates federal courts to apply the common law of the State where the court is.

U.S. District Judge David Ezra, who was the presiding judge in United States v. Goo, stated that he was adhering to the Lorenzo principle and that the defendant did not meet his burden of proof. The defendant was claiming that “he is immune from suit or judgment in any court of the United States or the State of Hawaii. Defendant contends that the State is illegally occupying the Kingdom, and thus the laws of the Kingdom should govern his conduct rather than any state or federal laws. Therefore, Defendant opposes an order from a federal court forcing him to pay “foreign” taxes through a foreclosure mechanism.”

In these proceedings, the Federal Defendants act as if there is no such thing as the Lorenzo principle, which is contrary to their position as the United States in the Goo case. The Federal Defendants managed to convince Judge Kobayashi that the case should be dismissed because the issue of whether the kingdom exists is a political question which does not allow the court to have jurisdiction. Without jurisdiction it wouldn’t be able to have an evidentiary hearing.

In none of the 53 cases that cited the Lorenzo principle did the courts invoke the political question doctrine. Even in the 17 federal cases that applied the Lorenzo principle, which includes Goo, did the courts invoke the political question doctrine. All stated the defendants failed to provide any evidence that the Hawaiian Kingdom still exists as a State.

The Lorenzo principle gives the State of Hawai‘i and the federal court limited jurisdiction to hear the evidence. If there is no evidence that the Hawaiian Kingdom still exists it maintains its jurisdiction. But if evidence shows that the Hawaiian Kingdom still exists, then the courts has no jurisdiction. In these proceedings, when the Federal Defendants fail to provide evidence that the Kingdom no longer exists, the Court will have to transform itself into an Article II Occupation Court in order to have jurisdiction over the complaint filed by the Hawaiian Kingdom.

The issue is not a “political question” but rather a “legal question” that the court has jurisdiction in order to hear the evidence. In another case that came before the ICA, in State of Hawai‘i v. Lee, ICA stated that the Lorenzo court “suggested that it is an open legal question whether the ‘Kingdom of Hawai‘i’ still exists.”

The Federal Defendants are attempting to make an end run on the football field and argue that the Hawaiian Kingdom cannot tackle them. It is an attempt by the Federal Defendants to overcome a difficulty without directly confronting it, which is precisely why judicial estoppel applies and judicial integrity is the primary function of judicial estoppel. Here is what federal courts of appeal say regarding judicial estoppel:

According to the First Circuit, judicial estoppel is to be used “when a litigant is ‘playing fast and loose with the courts,’ and when ‘international self-contradiction is being used as a means of obtaining unfair advantage in a forum provided for suitors seeking justice.’”

The Second Circuit states that judicial estoppel “is supposed to protect judicial integrity by preventing litigants from playing fast and loose with courts, thereby avoiding unfair results and unseemliness.”

The Third Circuit established a requirement that “the party changed his or her position in bad faith, i.e., in a culpable manner threatening to the court’s authority and integrity.”

The Fourth Circuit applies judicial estoppel to prevent litigants from “blowing hot and cold as the occasion demands.”

According to the Fifth Circuit, “litigants undermine the integrity of the judicial process when they deliberately tailor contradictory (as opposed to alternate) positions to the exigencies of the moment.”

The Sixth Circuit states that judicial estoppel “preserves the integrity of the courts by preventing a party from abusing the judicial process through cynical gamesmanship, achieving success on one position, then arguing the opposite to suit an exigency of the moment.”

The Seventh Circuit seeks to have judicial estoppel “to protect the judicial system from being whipsawed with inconsistent arguments.”

The Eighth Circuit says, “the purpose of judicial estoppel is to protect the integrity of the judicial process. As we read the caselaw, this is tantamount to a knowing misrepresentation to or even fraud on the court.”

The Ninth Circuit allows judicial estoppel to preclude “a party from gaining an advantage by taking one position, and then seeking a second advantage by taking an incompatible position.”

Observing that for judicial estoppel to apply, according to the Eleventh Circuit, the “inconsistencies must be shown to have been calculated to make a mockery of the judicial system.”

This inconsistent position taken by the Federal Defendants has placed the Hawaiian Kingdom in an unfair position. In its closing statement, the Hawaiian Kingdom stated:

“If the Federal Defendants are confident that “Plaintiff’s claim and assertions lack merit,” then let them make their case that the Hawaiian Kingdom “ceases to be a state” under international law pursuant to the Lorenzo principle that the Goo court adhered to. But they cannot prevail by having the Court muzzle the Plaintiff in its own case seeking justice under the rule of law.”

The United States knows that over a century of lies is coming to an end because there never was any evidence that the Hawaiian Kingdom no longer exists as a State. As Sir Walter Scott wrote in 1808, “Oh, what a tangled web we weave when first we practice to deceive.” It means that when you act dishonestly you are initiating problems, and a domino structure of complications, which will eventually run out of control.

This past Friday, August 12, 2022, District Judge Leslie Kobayashi filed a Minute Order taking under advisement the Hawaiian Kingdom’s Motion to Certify for interlocutory appeal her Order of July 28, 2022, denying the Hawaiian Kingdom’s motion for reconsideration of her previous Order granting the Federal Defendants motion to dismiss the amended complaint.

The Federal Defendants include Joseph Robinette Biden Jr., President of the United States; Kamala Harris, Vice-President of the United States; John Aquilino, Commander, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command; Charles P. Rettig, Commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service; Charles E. Schumer, U.S. Senate Majority Leader; and Nancy Pelosi, Speaker of the United States House of Representatives.

In their Motion to Dismiss, the Federal Defendants were claiming that this case presents a political question and that it should be dismissed. A political question means that since the United States has not recognized a nation as being sovereign and independent, the court’s will not adjudicate the case because the recognition of the sovereignty of that nation is first committed to the political branches of government. An example of a political question is Palestine. Because the United States has yet to recognize Palestine as an independent State, the federal courts deny access on matters relating to Palestine because it is a political question that the political branches have yet to recognize it.

The political question doctrine, however, does not apply in this case because the United States recognized the Hawaiian Kingdom as a sovereign and independent State on July 6, 1844, by letter of Secretary of State John C. Calhoun on behalf of President John Tyler, and later entered into treaty relations and the establishment of embassies and consulates in the two countries.

Also, Restatement (Third) of the Foreign Relations Law of the United States, §202, comment g, states that the United States’ “duty to treat a qualified entity as a state also implies that so long as the entity continues to meet those qualifications its statehood may not be ‘derecognized.’” The United States cannot now claim that it has de-recognized the Hawaiian Kingdom. It must show a treaty where the Hawaiian Kingdom merged with the United States, which would result in its extinguishment. No such treaty exists.

In her June 9, 2022 Order granting the Federal Defendants’ motion to dismiss, Judge Kobayashi stated, “Plaintiff bases its claims on the proposition that the Hawaiian Kingdom is a sovereign and independent State. However, ‘Hawaii is a state of the United States…. The Ninth Circuit, this court, and Hawai‘i state courts have rejected arguments asserting Hawaiian sovereignty.’” She then concludes, without reference to any evidence, “Plaintiff’s claims are ‘so patently without merit that the claims require no meaningful consideration.’”

The Hawaiian Kingdom filed a Motion for Reconsideration on June 15, 2022, because Judge Kobayashi’s Order is not in line with the court decisions she cited regarding the Hawaiian Kingdom. In its motion, the Hawaiian Kingdom brought to the attention of Judge Kobayashi the Lorenzo principle that stemmed from a 1994 appeals case, State of Hawai‘i v. Lorenzo, that came before the State of Hawai‘i Intermediate Court of Appeals (ICA). That case centered on whether or not the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist despite the unlawful overthrow of its government by the United States on January 17, 1893.

Lorenzo lost his appeal because the ICA stated, “Lorenzo has presented no factual (or legal) basis for concluding that the Kingdom exists as a state in accordance with recognized attributes of a state’s sovereign nature.” In other words, if Lorenzo did provide the evidence of the Kingdom’s existence as a State his appeal would have been granted and his criminal conviction by the trial court overturned.

In 2002, District Court Judge David Ezra, in United States v. Goo, stated, “This court sees no reason why it should not adhere to the Lorenzo principle.” What is surprising is that Judge Kobayashi was serving at the time as the Magistrate Judge under District Court Judge Ezra who made the decision that the court would “adhere to the Lorenzo principle.” The case centered on an Order issued by Magistrate Judge Kobayashi, which Judge Ezra affirmed. Judge Kobayashi cannot simply disregard the Lorenzo principle, when in fact the Lorenzo principle was used to confirm her Order as a Magistrate Judge.

In 2004, the ICA reiterated that a defendant has to provide evidence of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s existence as a State and not just say it exists. In State of Hawai‘i v. Araujo, the ICA stated:

Because Araujo has not, either below or on appeal, “‘presented any factual or legal basis for concluding that the Kingdom exists as a state in accordance with recognized attributes of a state’s sovereign nature,’” (citing Lorenzo, 77 Hawai‘i at 221, 883 P.2d at 643), his point of error on appeal must fail.

Finally, in 2014, the Hawai‘i Supreme Court, in State of Hawai‘i v. Armitage, clarified this evidentiary burden. The Supreme Court stated:

Lorenzo held that, for jurisdictional purposes, should a defendant demonstrate a factual or legal basis that the Kingdom “exists as a state in accordance with recognized attributes of a state’s sovereign nature,” and that he or she is a citizen of that sovereign state, a defendant may be able to argue that the courts of the State of Hawai‘i lack jurisdiction over him or her.

When Judge Kobayashi stated in her Order granting the Federal Defendants’ motion to dismiss that the “Ninth Circuit, this court, and Hawai‘i state courts have rejected arguments asserting Hawaiian sovereignty,” this is not an accurate statement. What the courts did conclude is that the defendants in those cases did not provide any evidence of the Kingdom’s existence as a State according to the Lorenzo principle. Instead, the defendants provided argument but not any evidence to support their argument. Judge Kobayashi’s statement would appear that these courts concluded the Hawaiian Kingdom does not exist as a State, which was clearly not the case.

Despite the Hawaiian Kingdom’s attempt to draw the attention of Judge Kobayashi to the Lorenzo principle and her errors, she issued an Order on July 28, 2022, denying the Hawaiian Kingdom’s request for reconsideration. She stated, “Although Plaintiff argues there are manifest errors of law in the 6/9/22 Order, Plaintiff merely disagrees with the Court’s decision. Plaintiff’s mere disagreement, however, does not constitute grounds for reconsideration.”

Normally, when one of the parties to a lawsuit wants to appeal a decision made by a federal judge they have to wait until the case is over. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals stated, “A district court order…is not appealable [under § 1291] unless it disposes of all claims as to all parties or unless judgment is entered in compliance with Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 54(b).” In other words, an Order is appealable while a case is still pending before the district court if it is in compliance with certain rules.

Federal statute 28 U.S.C. §1292(b) allows for Orders, called interlocutory orders, to be appealable if there is a difference of opinion regarding a controlling question of law. This is precisely what Judge Kobayashi stated in her Order denying the request for reconsideration. She stated, “Plaintiff merely disagrees with the Court’s decision.” This disagreement centers on a law that is supposed to be applied by the court in these proceedings. In this case, it would be the application of the Lorenzo principle.

Laws are not only legislative enactments but also include Appellate Court and Supreme Court decisions called common law. When there is no statute or law that would apply to a particular issue, the courts are allowed to make decisions that bind the lower courts when those type of matters come before the trial courts. Until a law is enacted on that particular matter or the highest court changes its decision, the common law would continue to apply at the district court level and bind the judges in their decisions.

The Hawaiian Kingdom filed its Motion to Certify so that the Ninth Circuit can review Judge Kobayashi’s Orders. Under §1292(b), the district court judge must first certify that the request to appeal an interlocutory order to the Ninth Circuit has met certain elements. §1292(b) states:

When a district judge, in making in a civil action an order not otherwise appealable under this section, shall be of the opinion that such order involves a controlling question of law as to which there is substantial ground for difference of opinion and that an immediate appeal from the order may materially advance the ultimate termination of the litigation, he shall so state in writing in such order. The Court of Appeals which would have jurisdiction of an appeal of such action may thereupon, in its discretion, permit an appeal to be taken from such order, if application is made to it within ten days after the entry of the order.

When a motion is filed in court proceedings, the other party, in this case the Federal Defendants, will have to file a motion to oppose or not oppose the filing. Dexter Ka‘iama, Attorney General for the Hawaiian Kingdom, spoke with the Department of Justice who is representing the Federal Defendants and told them that the Hawaiian Kingdom will be filing a motion for certification and asked if they would oppose or agree with the action. They told Attorney General Ka‘iama that they would oppose it.

The Hawaiian Kingdom was planning to respond to the Federal Defendants’ filing of their opposition with additional information it had found to support its Motion to Certify. However, when Judge Kobayashi filed her Order this past Friday, she stated, “that no response to the Certification Motion is necessary,” which means the Federal Defendants will not be filing their opposition as to why they oppose the motion to certify. They merely stated to Attorney General Ka‘iama that they will oppose it.

On Sunday, August 14, 2022, the Hawaiian Kingdom filed a Supplement to its Motion to Certify with the information it intended to reply to the Federal Defendants’ filing of their opposition. In its supplement to its motion, the Hawaiian Kingdom showed that there are other laws, along with the Lorenzo principle, to be the controlling law on this topic that Judge Kobayashi disregarded.

In its recent filing, the Hawaiian Kingdom expanded on the Lorenzo principle as the common law of the State of Hawai‘i. For the past 28 years, State of Hawai‘i v. Lorenzo was cited by the Hawai‘i Supreme Court in 8 cases, the most recent was in 2020. The ICA cited Lorenzo in 45 cases, the most recent was in 2021.

As common law of the State of Hawai‘i, Judge Kobayashi was bound to apply it in this case because of §34 of the Federal Judiciary Act of 1789, which is codified under 28 U.S.C. §1652:

The laws of the several states, except where the Constitution or treaties of the United States or Acts of Congress otherwise require or provide, shall be regarded as rules of decision in civil actions in the courts of the United States, in cases where they apply.

Reinforcing this statute, the United States Supreme Court, in Erie R.R. v. Tompkins, stated that “federal courts are bound to follow decisions of the courts of the State in which the controversies arise.” Judge Kobayashi cannot simply disregard 28 years of decisions by the State of Hawai‘i courts that say defendants must provide evidence that the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist as a State despite its government being unlawfully overthrown by the United States on January 17, 1893. The Hawaiian Kingdom also stated:

Further, it appears that the Court adopted a federal rule of decision to favor the United States despite its admitted illegal conduct regarding the overthrow of the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom on January 17, 1893. The application of the Lorenzo principle, as the common law of the State of Hawai‘i, should not be deemed by the Court to be incompatible with federal interests because it does not promote the interest of the United States. This is problematic because the federal court did adopt the Lorenzo principle as federal law in 17 cases, but this Court adopted a rule of decision—political question doctrine, in this one instance without any basis in law or fact, that unfairly advances the interest of the United States and shields them from accountability for its admitted unlawful conduct. This gives the impression that the Court is giving one party to the controversy an unfair advantage.

The Hawaiian Kingdom concluded:

Because the Court chose to supersede the decisions of the ICA and the Hawai‘i Supreme Court regarding the evidentiary basis of Lorenzo by invoking the political question doctrine in favor of the United States, the Court should certify for interlocutory appeal so that the Ninth Circuit can address this matter in the light of §1652, Erie, and the Lorenzo principle as controlling law in this case.