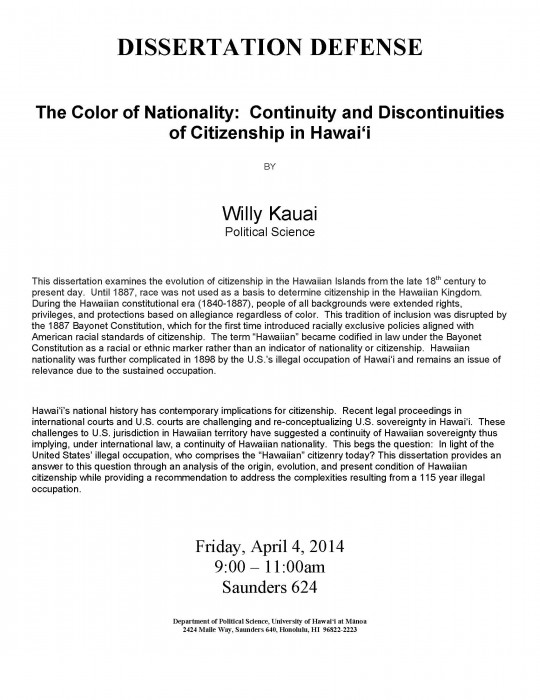

“Hawaiian Nationality” Dissertation Defense – Willy Kauai, Ph.D. candidate

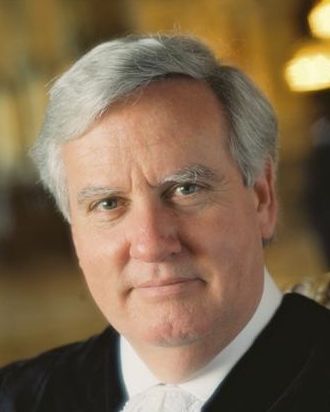

***UPDATE. Willy Kauai successfully defended his dissertation. He will be graduating in May 2014 with a Ph.D. in political science. His committee members were comprised of Professor Neal Milner, Chair, Professor Debora Halbert, Professor Charles Lawrence III, Dr. Keanu Sai, Professor Melody Kapilialoha MacKenzie, and Professor Puakea Nogelmeier.

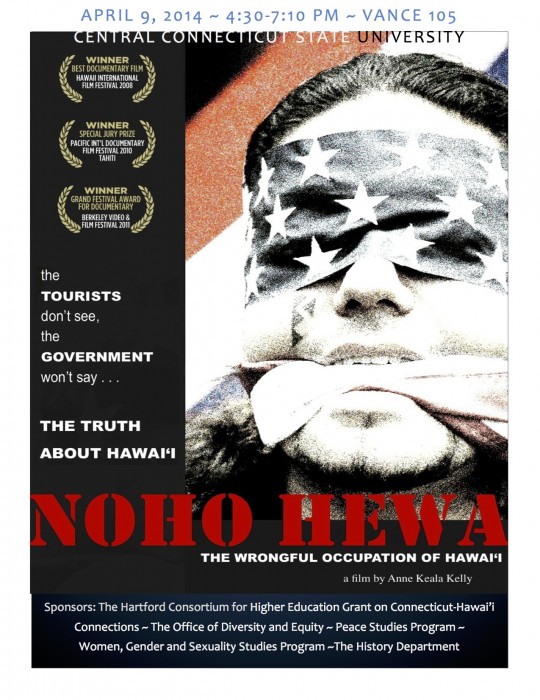

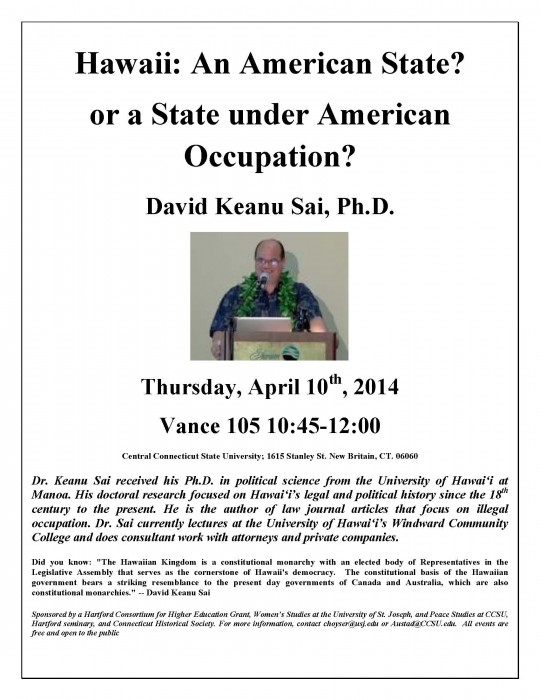

Dr. Keanu Sai to Present at Central Connecticut State University (CCSU) April 10th

Dr. Keanu Sai to Present at New York University (NYU) April 7th

Meeting at the Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law

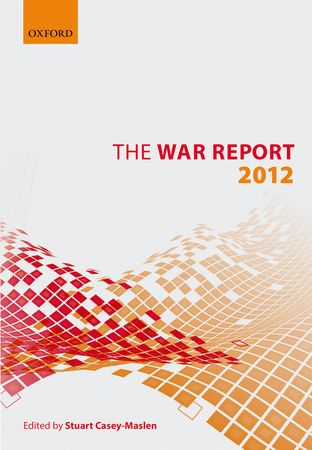

On the same day the Hawaiian Kingdom’s Envoy was meeting with the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs’ Directorate of International Law in Bern, Switzerland, on March 26, 2014, Dr. Keanu Sai was in a meeting with Dr. Stuart Casey-Maslen, head of research for the Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law in Geneva. The University of Lausanne, the International Committee of the Red Cross, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and the Swiss Federal Department for Foreign Affairs assists the Academy. The Academy is considering listing Hawai‘i as an occupied State.

At the meeting, Dr. Sai presented a power point presentation on the history of the Hawaiian Kingdom and how it came under an illegal and prolonged occupation. Dr. Maslen was also provided with information and evidence of the occupation. Dr. Maslen assured Dr. Sai that a decision will be made and if it has been determined that Hawai‘i is occupied according to the Academy’s criteria it will be listed on its website Rule of Law of Armed Conflict in June. The website provides monthly updates on armed conflicts and occupation and is currently under construction, but will be completed by June.

At the meeting, Dr. Sai presented a power point presentation on the history of the Hawaiian Kingdom and how it came under an illegal and prolonged occupation. Dr. Maslen was also provided with information and evidence of the occupation. Dr. Maslen assured Dr. Sai that a decision will be made and if it has been determined that Hawai‘i is occupied according to the Academy’s criteria it will be listed on its website Rule of Law of Armed Conflict in June. The website provides monthly updates on armed conflicts and occupation and is currently under construction, but will be completed by June.

Dr. Maslen is the editor of The War Report, which is a project of the Academy that identifies and briefly discusses armed conflicts according to the criteria established under international law. The War Report is a comprehensive global analysis of armed conflicts under international law, which includes military occupations. According to the Academy, “The purpose of The War Report is to collect information in the public domain and provide legal analysis for governments, policy makers, the United Nations, academics, NGOs, and journalists.”

Dr. Maslen is the editor of The War Report, which is a project of the Academy that identifies and briefly discusses armed conflicts according to the criteria established under international law. The War Report is a comprehensive global analysis of armed conflicts under international law, which includes military occupations. According to the Academy, “The purpose of The War Report is to collect information in the public domain and provide legal analysis for governments, policy makers, the United Nations, academics, NGOs, and journalists.”

“The classification of an armed conflict under international law is an objective legal test and not a decision left to national governments or any international body, not even the UN Security Council,” says Andrew Clapham, Director of the Academy and Graduate Institute Professor in International Law. “It is not always clear when a situation is an armed conflict, and hence when war crimes can be punished,” added Professor Clapham. “The War Report aims to change this and bring greater accountability for criminal acts perpetuated in armed conflicts.”

“The classification of an armed conflict under international law is an objective legal test and not a decision left to national governments or any international body, not even the UN Security Council,” says Andrew Clapham, Director of the Academy and Graduate Institute Professor in International Law. “It is not always clear when a situation is an armed conflict, and hence when war crimes can be punished,” added Professor Clapham. “The War Report aims to change this and bring greater accountability for criminal acts perpetuated in armed conflicts.”

The Academy’s listing of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an occupied State will promote accountability for individuals who have committed war crimes in the Hawaiian Islands where prosecution can take place before the International Criminal Court and as well as by countries that have universal jurisdiction such as the Philippines and Germany.

Swiss Foreign Ministry Meets With Hawaiian Envoy in Bern

Due to the war crimes that continue to be committed with impunity by the State of Hawai‘i, an illegal regime, against innocent civilians, the acting government of the Hawaiian Kingdom has temporarily refrained from pursuing its proceedings at the International Court of Justice and has decided to focus its attention to secure a Protecting Power pursuant to the Fourth Geneva Convention (GCIV) and the Additional Protocol I (API). A Protecting Power is a State that ensures compliance of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States to the provisions of the GCIV and API, with particular focus on the protection of civilians.

As a State Party to the GCIV and AP, article 5(1) of the API, states, “It is the duty of the Parties to a conflict from the beginning of that conflict to secure the supervision and implementation of the Conventions and of this Protocol by the application of the system of Protecting Powers, including inter alia the designation and acceptance of those Powers, in accordance with the following paragraphs.” And according to article 5(3) of the API, if a Protecting Power has not been designated, “the International Committee of the Red Cross…shall offer its good offices to the Parties to the conflict with a view to the designation without delay of a Protecting Power to which the Parties to the conflict consent.”

On December 18, 2013, at its headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) was formally requested to assist the Hawaiian Kingdom in securing a Protecting Power in accordance with the GCIV and API. In this pursuit, the acting government has been in the process of securing a meeting with the Swiss government in order to formally request that it be a Protecting Power and to work with the ICRC. The Swiss government has a long history of serving as a mediator to international conflicts and did serve as a protecting power in the past. A meeting was secured on March 26, 2014, and the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs’ Directorate of International Law in Bern, Switzerland, received the acting government’s Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary. Negotiations to secure Switzerland as a Protecting Power for the illegal and prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom have begun.

Hawai‘i and the Namibia Exception

According to international law, the United States Federal government and the United States’ State of Hawai‘i government operating within the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom are illegal regimes. Article 43 of the Hague Convention, IV, mandates that the occupying State, the United States, to administer the laws of the occupied State, the Hawaiian Kingdom. According to Professor Marco Sassoli, Article 43 of the Hague Regulations and Peace Operations in the Twenty-first Century, p. 5, “Article 43 does not confer on the occupying power any sovereignty over the occupied territory. The occupant may therefore not extend its own legislation over the occupied territory nor act as a sovereign legislator. It must, as a matter of principle, respect the laws in force in the occupied territory at the beginning of the occupation.”

These illegal regimes are and have been administering United States law and not Hawaiian law in an attempt to conceal the prolonged and illegal occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom. According to Dr. Yaël Ronen, Status of Settlers Implanted by Illegal Regimes under International Law (2008), p. 2, “Illegal regimes often transfer of their own populations or populations loyal to them in the territory, and subsequently grant these populations residence or nationality in the territory. This is done in order to change the demographic composition of the territory under dispute and thereby solidify the regime.”

When another country’s government is operating within the territory of another country without title or sovereignty, every official action taken by that regime is illegal and void except for its registration of births, marriages and deaths. This is called the “Namibia exception,” which is a decision by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in 1971 called the Legal Consequences for States of the Continued Presence of South Africa in Namibia (South West Africa) notwithstanding Security Council Resolution 276 (1970).

In 1966, the United Nations General Assembly passed resolution 2145 (XXI) that terminated South Africa’s administration of Namibia, formerly known as South West Africa, a former German colony. This resulted in Namibia coming under the administration of the United Nations, but South Africa refused to withdraw from Namibian territory and consequently the situation transformed into an illegal occupation. As a former German colony, Namibia became a mandate territory under the administration of South Africa after the close of the First World War.

Addressing the legal consequences arising for South Africa’s refusal to leave Namibia, the ICJ stated that by “occupying the Territory without title, South Africa incurs international responsibilities arising from a continuing violation of an international obligation,” and that all countries, whether a member of the United Nations or not were “under an obligation to recognize the illegality and invalidity of South Africa’s continued presence in Namibia and to refrain from lending any support or any form of assistance to South Africa with reference to its occupation of Namibia.” The ICJ, however, clarified that “non-recognition should not result in depriving the people of Namibia of any advantages derived from international cooperation.

The conduct of an illegal regime during occupation is limited and confined to the international laws of occupation and to the principle of ex injuria ius non oritur—where unlawful acts cannot be the source of lawful rights. According to Ronen, p. 39, “Opposite the principle of ex injuria jus non oritur operates the principle ex factis ius oritur. It mandates that acts of the illegal regime may have legal consequences despite the illegality and status of the regime that performed them.” Ronen explains, “In other words, the general invalidity of domestic acts carried out under an illegal regime is qualified where such invalidity would act to the detriment of the inhabitants of the territory. This is the Namibia exception.” The ICJ in the Namibia case explained, “the principle ex injuria jus non oritur dictates that acts which are contrary to international law cannot become a source of legal acts for the wrongdoer… To grant recognition to illegal acts or situation will tend to perpetuate it and be benefitial to the state which has acted illegally.”

The focus of the Namibia exception is to protect the interests of the nationals of the occupied State and not to entrench the authority of an illegal regime. The validity of any other official acts of an illegal regime other than the registration of births, marriages and deaths must not serve “to the detriment of the inhabitants of the territory” being occupied and must not be seen to further “entrench the authority of an illegal regime.”

The Hawaiian Kingdom at the Permanent Court of Arbitration (1999-2001)

https://vimeo.com/17007826

On November 8, 1999, international arbitration proceedings were initiated at the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA), The Hague, Netherlands, between Lance Paul Larsen and the acting Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom (Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom). The arbitration agreement provided, “The Arbitral Tribunal is asked to determine, on the basis of the Hague Conventions IV and V of 18 October 1907, and the rules and principles of international law, whether the rights of the Claimant under international law as a Hawaiian subject are being violated, and if so, does he have any redress against the Respondent Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom?”

Larsen was arrested on October 4, 1999, in Hilo, Hawai‘i, and imprisoned for 30 days, seven of which were in solitary confinement, for following Hawaiian Kingdom law. Larsen, as the Claimant, alleged that the acting government, the Respondent, was  legally liable to him for allowing the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws over him within the territorial jurisdiction of the Hawaiian Kingdom. In the pleading, Larsen’s attorney, Ms. Ninia Parks, esq., based her case on the following grounds:

legally liable to him for allowing the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws over him within the territorial jurisdiction of the Hawaiian Kingdom. In the pleading, Larsen’s attorney, Ms. Ninia Parks, esq., based her case on the following grounds:

- Mr. Larsen is a Hawaiian subject, with a Hawaiian nationality.

- As a Hawaiian subject, Mr. Larsen is bound by Hawaiian Kingdom law. He is not bound by the laws of the State of Hawaii nor by the laws of the United States of America.

- Mr. Larsen’s rights as a Hawaiian subject have been systematically and continuously denied by the United States of America, the occupying force in the prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian islands by the United States of America. At a minimum, the United States of America has continually denied Mr. Larsen’s nationality as a Hawaiian subject, has illegally imposed American laws over his person, has extorted monetary fines from Mr. Larsen under threat of imprisonment, and has imprisoned Mr. Larsen for asserting his lawful rights as a Hawaiian national.

- The government of the Hawaiian Kingdom has a duty to protect the rights of Mr. Larsen, a Hawaiian subject, despite the continued occupation of the Hawaiian Islands by the United States of America.

- The government of the Hawaiian Kingdom, through its acting Regency, has not fulfilled this duty.

In its pleading, the acting Government, represented by Dr. Keanu Sai as lead agent, denied the allegations and submitted “that the Claimant’s rights under international law are being violated, but to what extent, is left to the Arbitral Tribunal to decide. That this decision must be made within fixed and established principles and laws pertaining to the matter, and that the Hawaiian Kingdom Government is not liable for redress of these violations under its present conditions as an occupied State.”

In its pleading, the acting Government, represented by Dr. Keanu Sai as lead agent, denied the allegations and submitted “that the Claimant’s rights under international law are being violated, but to what extent, is left to the Arbitral Tribunal to decide. That this decision must be made within fixed and established principles and laws pertaining to the matter, and that the Hawaiian Kingdom Government is not liable for redress of these violations under its present conditions as an occupied State.”

In the American Journal of International Law, vol. 95, p. 928 (2001), and reprinted in the Hawaiian Journal of Law and Politics, vol. 1, p. 83 (2004), Bederman and Hilbert, state that at “the center of the PCA proceeding was…that the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist and that the Hawaiian Council of Regency (representing the Hawaiian Kingdom) is legally responsible under international law for the protection of Hawaiian subjects, including the claimant. In other words, the Hawaiian Kingdom was legally obligated to protect Larsen from the United States’ ‘unlawful imposition [over him] of [its] municipal laws’ through its political subdivision, the State of Hawai‘i. As a result of this responsibility, Larsen submitted, the Hawaiian Council of Regency should be liable for any international law violations that the United States committed against him.”

In February 2000, the PCA’s Secretary General Tjaco T. van den Hout recommended that the acting Government provide a formal invitation to the United States to join in the arbitration. In order to carry out this request by the Secretary General, Dr. Sai was sent to Washington, D.C. Ms. Ninia Parks, attorney for the Claimant Lance Larsen, accompanied Dr. Sai.

In February 2000, the PCA’s Secretary General Tjaco T. van den Hout recommended that the acting Government provide a formal invitation to the United States to join in the arbitration. In order to carry out this request by the Secretary General, Dr. Sai was sent to Washington, D.C. Ms. Ninia Parks, attorney for the Claimant Lance Larsen, accompanied Dr. Sai.

On March 3, 2000, a telephone meeting with John R. Crook, Assistant Legal Adviser for United Nations Affairs section of the US Department of State, was held. It was stated to Mr. Crook that the “visit was to provide these documents to the Legal Department of the U.S. Department of State in order for the U.S. Government to be apprised of the arbitral proceedings already in train and that the Hawaiian Kingdom, by consent of the Claimant, extends an opportunity for the United States to join in the arbitration as a party.”

On March 3, 2000, a telephone meeting with John R. Crook, Assistant Legal Adviser for United Nations Affairs section of the US Department of State, was held. It was stated to Mr. Crook that the “visit was to provide these documents to the Legal Department of the U.S. Department of State in order for the U.S. Government to be apprised of the arbitral proceedings already in train and that the Hawaiian Kingdom, by consent of the Claimant, extends an opportunity for the United States to join in the arbitration as a party.”

Mr. Crook was made fully aware of the United States occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the establishment of the acting Government. This direct challenge to US sovereignty over the Hawaiian Islands should have prompted the United States to protest the action taken by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in accepting the Hawaiian arbitration case and call upon the Secretary General to cease and desist because this action constitutes a violation of US sovereignty. The United States did  neither. Instead, Deputy Secretary General Phyllis Hamilton notified the acting Government that the United States notified the Court that it will not join in the arbitration, but did request from the acting government permission to access all pleadings and transcripts of the case. Both the acting government and Larsen’s attorney consented. By this action, the United States directly acknowledged the circumstances of the proceedings and the acting government’s representation of the Hawaiian Kingdom before an international tribunal.

neither. Instead, Deputy Secretary General Phyllis Hamilton notified the acting Government that the United States notified the Court that it will not join in the arbitration, but did request from the acting government permission to access all pleadings and transcripts of the case. Both the acting government and Larsen’s attorney consented. By this action, the United States directly acknowledged the circumstances of the proceedings and the acting government’s representation of the Hawaiian Kingdom before an international tribunal.

Three distinguished jurists presided on the Arbitration Tribunal. Professor James Crawford, SC, served as Presiding arbitrator. Professor Crawford is a professor of international law at the University of Cambridge. At the time of the arbitration, Crawford was also a member of the United Nations International Law Commission (ILC) and was responsible for the ILC’s work on the International Criminal Court (1994) and the Articles on State Responsibility (2001).

Three distinguished jurists presided on the Arbitration Tribunal. Professor James Crawford, SC, served as Presiding arbitrator. Professor Crawford is a professor of international law at the University of Cambridge. At the time of the arbitration, Crawford was also a member of the United Nations International Law Commission (ILC) and was responsible for the ILC’s work on the International Criminal Court (1994) and the Articles on State Responsibility (2001).

Judge Sir Christopher Greenwood, QC, served as Associate arbitrator. Greenwood was at the time professor of international law at the London School of Economics and Political Science and legal counsel to the United Nations on the Laws of War and Occupation. In 2008, the United Nations elected Greenwood to be judge on the International Court of Justice.

Judge Sir Christopher Greenwood, QC, served as Associate arbitrator. Greenwood was at the time professor of international law at the London School of Economics and Political Science and legal counsel to the United Nations on the Laws of War and Occupation. In 2008, the United Nations elected Greenwood to be judge on the International Court of Justice.

Dr. Gavan Griffith, QC, served as Associate Arbitrator. Griffith was former Solicitor General for Australia and also served as counsel and agent for Australia in Nauru v. Australia before the International Court of Justice.

Dr. Gavan Griffith, QC, served as Associate Arbitrator. Griffith was former Solicitor General for Australia and also served as counsel and agent for Australia in Nauru v. Australia before the International Court of Justice.

Three days of oral hearings were set for December 7, 8 and 11, 2000 at the PCA. At the center of these proceedings was whether or not Larsen was able to maintain his suit against the acting Government for not protecting him without the participation of the United States who would need to answer to the alleged violations committed by them against Larsen. Larsen was attempting to hold the acting Government responsible for his injuries committed by the United States. In international law, this is a situation called the “necessary and indispensable party” rule and it was the basis of decisions made by the International Court of Justice in Monetary Gold case (Italy v. France, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and United States of America), the Nauru case (Nauru v. Australia), and the East Timor case (Portugal v. Australia).

In the 2001 Arbitral Award, the Tribunal explained, that it “cannot determine whether the Respondent [the acting government] has failed to discharge its obligations towards the Claimant [Larsen] without ruling on the legality of the acts of the United States of America. Yet that is precisely what the Monetary Gold principle precludes the Tribunal from doing. As the International Court explained in the East Timor case, ‘the Court could not rule on the lawfulness of the conduct of a State when its judgment would imply an evaluation of the lawfulness of the conduct of another State which is not a party to the case.’”

The Tribunal, however, did acknowledge the Hawaiian Kingdom to be an independent State. In its decision, the Tribunal concluded in the Award, “that in the nineteenth century the Hawaiian Kingdom existed as an independent State recognized as such by the United States of America, the United Kingdom and various other States, including by exchanges of diplomatic or consular representatives and the conclusion of treaties.” International law provides for the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom since the nineteenth century to the present, which was the basis for the arbitration case in the first place.

‘Iolani School Students Reenact Historical Trial at ‘Iolani Palace

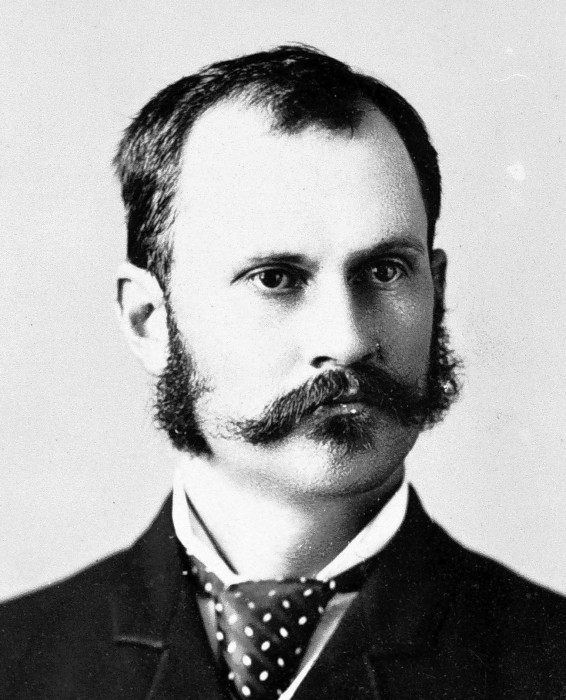

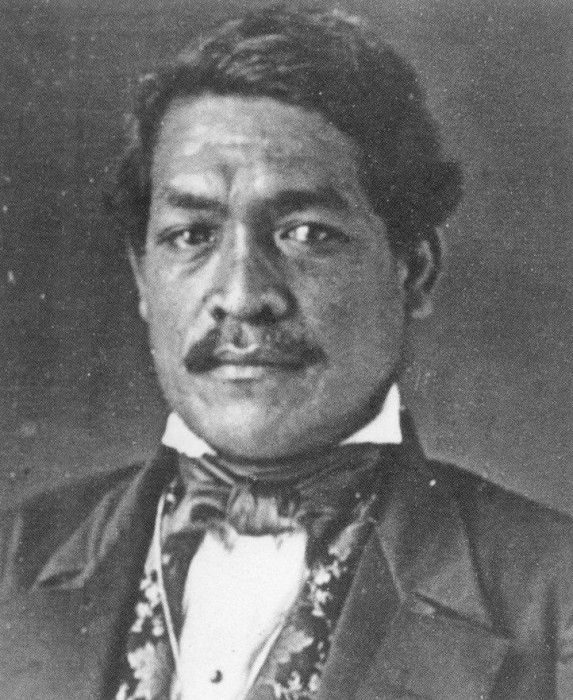

On March 6, 2014, KITV News aired a story where ‘Iolani School students reenacted a historical trial of Lorrin Thurston, who was the lead insurgent when the United States illegally overthrew the Hawaiian Kingdom government in 1893, was put on trial for treason. Thurston was a Hawaiian subject and an attorney in the Hawaiian Kingdom. He was the leader of the insurgency that got the U.S. Ambassador John Stevens to land U.S. troops to protect them from arrest by the Hawaiian authorities in order to declare themselves and new government. U.S. Special Commissioner James Blount who was appointed by President Grover Cleveland to investigate whether or not U.S. troops were involved, concluded, “in pursuance of a prearranged plan, the Government thus established hastened off commissioners to Washington to make a treaty for the purpose of annexing the Hawaiian Islands to the United States.”

On March 6, 2014, KITV News aired a story where ‘Iolani School students reenacted a historical trial of Lorrin Thurston, who was the lead insurgent when the United States illegally overthrew the Hawaiian Kingdom government in 1893, was put on trial for treason. Thurston was a Hawaiian subject and an attorney in the Hawaiian Kingdom. He was the leader of the insurgency that got the U.S. Ambassador John Stevens to land U.S. troops to protect them from arrest by the Hawaiian authorities in order to declare themselves and new government. U.S. Special Commissioner James Blount who was appointed by President Grover Cleveland to investigate whether or not U.S. troops were involved, concluded, “in pursuance of a prearranged plan, the Government thus established hastened off commissioners to Washington to make a treaty for the purpose of annexing the Hawaiian Islands to the United States.”

To view the KITV news coverage of the historical trial go to this link.

‘Iolani School is a private school that was established in 1863 by Father William R. Scott of the Anglican faith. The former name of the school was Lua‘ehu, but it was renamed ‘Iolani in 1870 by the former Queen Emma when it moved from the city of Lahaina to Honolulu. The school’s patron saints are King Kamehameha IV and Queen Emma.

Here is the transcript of KITV’s coverage.

HONOLULU —The ‘Iolani palace throne room, the very room where former Queen Lili’uokalani was put on trial for treason, was turned into a court room Thursday.

At first glance you feel like you have been transported back in time to the trial of Lili’uokalani. The palace throne room was set up for the case, but well over a century later comes a twist; Iolani School history students are putting Lorrin Thurston on trial.

Thurston played a prominent role in the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarch; the witnesses historical figures of that time.

“How do you feel about Lorrin Thurston and his overthrow of Hawaii? I believe he’s guilty. He led the overthrow. He acted on his own accord. He started the Committee of Safety and he also wrongfully used the U.S. Navy as intimidation during the coup,” said Senator James Blount, author of the Blount Report. “You did not take the opinion of the coup? I didn’t have them for my report. I envied the local population. Why? Cause they would have been biased.”

Taking their assignment seriously most dressed the part and sounded the part too.

“The Angle Franco Treaty…I agreed to recognize the Hawaiian Kingdom as a sovereign,” said Queen Victoria, a friend of Queen Lili’uokalani.

“I didn’t betray her. I did what I thought would be best for the people,” said Sanford Dole, President of the Republic of Hawaii.

“Did the annexation of Hawaii benefit the landowner more or was it made for the people — the Native Hawaiians? It was for everyone living in Hawaii,” said Max Webber, an Iolani School 12th grader playing Thurston.

After a brief deliberation, the jury decides.

“Your honor, we the jury find Lorrin Thurston guilty of the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom,” said a student cast in the jury.

A sigh came from Weber, who played Thurston and dove right into the project.

“I read there all these books about him and he had a book he wrote about himself. So, I went through and read a lot of that and I also ideas of what he was thinking during that time,” said Weber.

“‘Iolani Palace is taking a new initiative to focus more on education and going outside of the four walls of the classrooms is so much more effective,” said ‘Iolani Palace Executive Director Kippen de alba Chu

Iolani School history teacher Melanie Pfingstem, who played the judge, agrees.

“Well I just think that simulations are really a great way for kids to internalize history,” said Pfingstem.

“This whole experience has really given us the details and the exact circumstances around the overthrow and the part each player played. That was really eye opening to how Hawaii became what it is today,” Michelle Kimura, an Iolani School 10th grader who portrayed Lili’uokalani.

Hawai‘i and the Crimean Crisis – Obama is not a Legitimate President

Putting aside the violence that has caused injuries and death in Ukraine on both the government and protesters side, what does the law say regarding the removal of Ukraine’s President Victor Yanukovych by vote of the Ukrainian Parliament (Rada). In The Daily Beast article “How Ukraine’s Parliament Brought Down Yanukovych,” there was no mention of Ukrainian law, except for legislation passed by the Rada. The Daily Beast reported, “after Yanukovych refused to leave office, the Ukrainian parliament by an overwhelming majority voted to remove him from the post as the one who ‘has dissociated himself’ by fleeing the capital. The ballot was passed with a constitutional majority and entered into force immediately.”

Putting aside the violence that has caused injuries and death in Ukraine on both the government and protesters side, what does the law say regarding the removal of Ukraine’s President Victor Yanukovych by vote of the Ukrainian Parliament (Rada). In The Daily Beast article “How Ukraine’s Parliament Brought Down Yanukovych,” there was no mention of Ukrainian law, except for legislation passed by the Rada. The Daily Beast reported, “after Yanukovych refused to leave office, the Ukrainian parliament by an overwhelming majority voted to remove him from the post as the one who ‘has dissociated himself’ by fleeing the capital. The ballot was passed with a constitutional majority and entered into force immediately.”

President Obama calls the new government legitimate, but President Putin calls it illegitimate. According to Article 108 of the Ukrainian Constitution, “The authority of the President of Ukraine shall be subject to an early termination in cases of: (1) resignation; (2) inability to exercise presidential authority for health reasons; (3) removal from office by the procedure of impeachment; (4) his/her death.” Since Yanukovych didn’t resign and he had no health issues, the only way to remove him would be “by the procedure of impeachment.” The quintessential question is whether a vote of removal by the Rada constituted impeachment. If it was then Yanukovych is no longer President, but if not then the Rada vote was unconstitutional and Yanukovych is still President even while he is in Russia.

President Obama calls the new government legitimate, but President Putin calls it illegitimate. According to Article 108 of the Ukrainian Constitution, “The authority of the President of Ukraine shall be subject to an early termination in cases of: (1) resignation; (2) inability to exercise presidential authority for health reasons; (3) removal from office by the procedure of impeachment; (4) his/her death.” Since Yanukovych didn’t resign and he had no health issues, the only way to remove him would be “by the procedure of impeachment.” The quintessential question is whether a vote of removal by the Rada constituted impeachment. If it was then Yanukovych is no longer President, but if not then the Rada vote was unconstitutional and Yanukovych is still President even while he is in Russia.

By definition, impeachment is not removal, but rather a process initiated by a legislative body in order to remove a President. Impeachment is similar to an indictment, which precedes a trial. Under the United States Constitution this two-step process begins when the House of Representatives votes for articles of impeachment by a majority of  those Representatives present, which provides the allegations of “treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.” If the articles of impeachment pass, the President is considered impeached. What follows is for the Senate to hold a trial, which is presided over by the Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1999, President Bill Clinton was impeached, but was found not guilty in the Senate trial.

those Representatives present, which provides the allegations of “treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.” If the articles of impeachment pass, the President is considered impeached. What follows is for the Senate to hold a trial, which is presided over by the Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1999, President Bill Clinton was impeached, but was found not guilty in the Senate trial.

The Ukrainian Constitution provides for the process of impeaching its President.

“Article 111. The President of Ukraine may be removed from the office by the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine in compliance with a procedure of impeachment if he commits treason or other crime.

The issue of the removal of the President of Ukraine from the office in compliance with a procedure of impeachment shall be initiated by the majority of the constitutional membership of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine.

The Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine shall establish a special ad hoc investigating commission, composed of special prosecutor and special investigators to conduct an investigation.

The conclusions and proposals of the ad hoc investigating commission shall be considered at the meeting of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine.

On the ground of evidence, the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine shall, by at least two-thirds of its constitutional membership, adopt a decision to bring charges against the President of Ukraine.

The decision on the removal of the President of Ukraine from the office in compliance with the procedure of impeachment shall be adopted by the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine by at least three-quarters of its constitutional membership upon a review of the case by the Constitutional Court of Ukraine, and receipt of its opinion on the observance of the constitutional procedure of investigation and consideration of the case of impeachment, and upon a receipt of the opinion of the Supreme Court of Ukraine to the effect that the acts, of which the President of Ukraine is accused, contain elements of treason or other crime.”

The Rada’s vote to remove President Yanukovych does not appear to be following this constitutional process and it can be argued that Yanukovych’s removal was  unconstitutional, which is what Russia has been stating. Russia

unconstitutional, which is what Russia has been stating. Russia also has stated that Yanukovych’s removal was supported by the United States, especially after a phone conversation between assistant U.S. Secretary of State Victoria Nuland and U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine, Geoffrey Pyatt, was leaked to the media. On February 7, 2014, The Guardian reported on the phone conversation and played the audio.

also has stated that Yanukovych’s removal was supported by the United States, especially after a phone conversation between assistant U.S. Secretary of State Victoria Nuland and U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine, Geoffrey Pyatt, was leaked to the media. On February 7, 2014, The Guardian reported on the phone conversation and played the audio.

With the world’s focus on whether Yanukovych is still President according to Ukrainian law and not international law, there is a question of Presidential legitimacy the world may not know, which is the legitimacy of United States President Barrack Obama under United States law. Article II of the United States Constitution provides, “No Person except a natural born Citizen, or a Citizen of the United States, at the time of the Adoption of this Constitution, shall be eligible to the Office of President.” The term natural born (jus soli) is a person who acquires United States citizenship through birth on United States territory. This is different from U.S. citizenship acquired through naturalization, which has a residency requirement, and U.S. citizenship acquired through parentage (jus sanguinis) when born outside of the United States.

The leading case in the United States on the definition of “natural-born” is the 1898 U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in U.S. v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649. In that case, the Court confirmed that Wong Kim Ark, a child of Chinese nationals born in the city of San Francisco, was a natural-born United States citizen. The Court’s reasoning was that since the term “natural-born” was specifically used in the United States Constitution, which was written in 1787, English common law was to be used in its interpretation of natural-born. The Court explained, “The interpretation of the Constitution of the United States is necessarily influenced by the fact that its provisions are framed in the language of the English common law, and are to be read in the light of its history.”

The leading case in the United States on the definition of “natural-born” is the 1898 U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in U.S. v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649. In that case, the Court confirmed that Wong Kim Ark, a child of Chinese nationals born in the city of San Francisco, was a natural-born United States citizen. The Court’s reasoning was that since the term “natural-born” was specifically used in the United States Constitution, which was written in 1787, English common law was to be used in its interpretation of natural-born. The Court explained, “The interpretation of the Constitution of the United States is necessarily influenced by the fact that its provisions are framed in the language of the English common law, and are to be read in the light of its history.”

The Court further explained, “The fundamental principle of the common law with regard to English nationality was birth within the allegiance, also called ‘ligealty,’ ‘obedience,’ ‘faith,’ or ‘power’ of the King. The principle embraced all persons born within the King’s allegiance and subject to his protection. Such allegiance and protection were mutual — as expressed in the maxim protectio trahit subjectionem, et subjectio protectionem — and were not restricted to natural-born subjects and naturalized subjects, or to those who had taken an oath of allegiance, but were predicable of aliens in amity so long as they were within the kingdom. Children, born in England, of such aliens were therefore natural-born subjects. But the children, born within the realm, of foreign ambassadors, or the children of alien enemies, born during and within their hostile occupation of part of the King’s dominions, were not natural-born subjects because not born within the allegiance, the obedience, or the power, or, as would be said at this day, within the jurisdiction, of the King.”

Two of the Judges, however, dissented with the judgment on racial grounds, but they also allude to what it meant to children born abroad of U.S. parents. Both judges stated, “Considering the circumstances surrounding the framing of the Constitution, I submit that it is unreasonable to conclude that ‘natural-born citizen’ applied to everybody born within the geographical tract known as the United States, …while children of our citizens, born abroad, were not.”

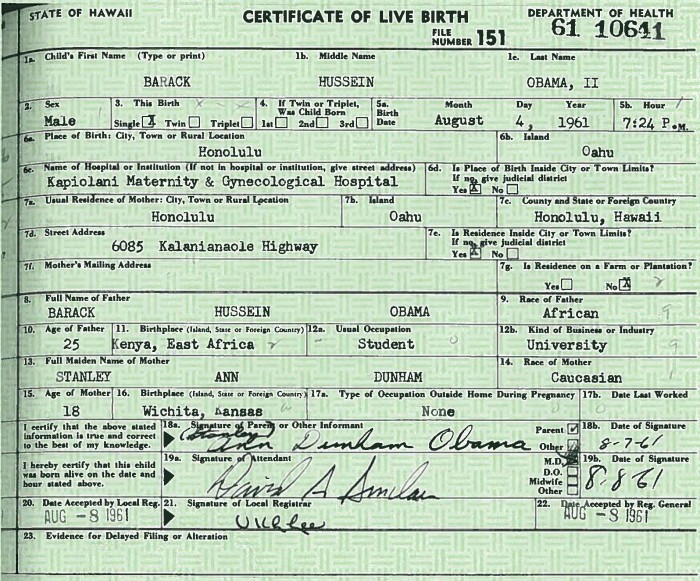

Obama was born in the Hawaiian Kingdom and not the United States. He was born in the city of Honolulu on August 4, 1961 at Kapi‘olani Hospital, which was established in 1890 by the Hawaiian Kingdom’s Queen Kapi‘olani.

Since the Hawaiian Kingdom has been under an illegal and prolonged occupation by the United States and its continuity is protected under international law, Obama cannot claim to be a natural-born citizen of the United States and, therefore, cannot meet the constitutional requirement to be a President of the United States. But he is a U.S. citizen through parentage (jus sanguinis) because his mother was a U.S. citizen when she gave birth to Obama in the Hawaiian Kingdom. He cannot, however, claim Hawaiian citizenship by birth because the international law of occupation, which protects and maintains the status quo of the occupied State, only allows Hawaiian citizenship through parentage and not natural-born even though it is a recognized mode of acquiring citizenship under Hawaiian Kingdom law.

Hawai‘i and the Crimean Conflict

Today on CNN’s coverage of the “Crisis in Ukraine” at 3:31pm (Eastern Time), news anchor Brooke Baldwin made a very interesting comment. Baldwin stated, “Ukrainian officials believe 30,000 Russian troops are now there in that small peninsula about the size of Hawai‘i.” This is a very interesting comparison by CNN to make reference to Hawai‘i with the Crimean conflict, especially when it would appear that CNN has no knowledge, or do they, of Hawai‘i’s direct link to Crimea regarding Hawaiian neutrality and the correlation between the argument of Russian intervention and United States intervention in the Hawaiian Kingdom. CNN also reported that Russia warns U.S. that threatened sanctions will “boomerang.”

Today on CNN’s coverage of the “Crisis in Ukraine” at 3:31pm (Eastern Time), news anchor Brooke Baldwin made a very interesting comment. Baldwin stated, “Ukrainian officials believe 30,000 Russian troops are now there in that small peninsula about the size of Hawai‘i.” This is a very interesting comparison by CNN to make reference to Hawai‘i with the Crimean conflict, especially when it would appear that CNN has no knowledge, or do they, of Hawai‘i’s direct link to Crimea regarding Hawaiian neutrality and the correlation between the argument of Russian intervention and United States intervention in the Hawaiian Kingdom. CNN also reported that Russia warns U.S. that threatened sanctions will “boomerang.”

What is at the center of the Ukrainian crisis is “intervention,” and whether or not international law has been violated. The United States says yes, but Russia says no. The international law on intervention is clearly prohibitive, but there are exceptions according to Oppenheim, International Law, vol. 1, (7th ed. 1948), p. 274. The two exceptions that appear to be in line with the Crimean conflict are, first, where restrictions on a treaty are not being complied with, and, second, the rights of citizens of the intervening State are being threatened.

Restrictive Treaty

The treaty that the United States consistently makes reference to as to why Russian actions in the Crimea is a violation of international law is the 1997 Friendship Treaty between Ukraine and Russia. At the ceremonies in Kiev, Russian President Boris Yeltsin, declared, “We respect and honor the territorial integrity of Ukraine.” A State’s territorial integrity, however, is protected by international law and not just by a treaty. International law provides that “the territorial integrity and political independence of the State are inviolable.” This treaty does not appear to be President Vladimir Putin’s justification for Russian action in the Crimea. Instead, Putin appears to refer to the treaty that centers on the Russian Naval Base at Sevastopol.

In the aftermath of the breakup of the Soviet Union, Russia negotiated the fate of its military bases that were located outside of Russian territory. Russia’s Naval Base at Sevastopol in Crimea dates back to 1783 when the Russian Prince Grigory Potemkin founded the port city. In 1997, Russia and Ukraine signed a Partition Treaty whereby Russia would maintain its naval base after purchasing 81.7% of Ukraine’s naval ships for $526.5 million dollars as reported by RT News. This treaty was ratified in 1999 by both governments. The treaty allows the Russian Black Sea Fleet to remain in Crimea until 2042. Russia claims that the new government in Kiev is not legitimate and its anti-Russian rhetoric a threat to its Naval Base at Sevastopol and the maintenance of the 1997 Partition Treaty. According to international law, this would be a justification for intervention and it would appear that Putin is correct in that Russia is complying with international law.

At this stage, Russia has not deployed its troops into Ukraine even though the Russian Parliament authorized Putin the authority to do so. What has taken place in Crimea is not an invasion, but rather actions taken by Russian troops that were already stationed in Crimea at its Naval Base in Sevastopol. The 1997 Partition Treaty allows for 25,000 Russian troops, 24 artillery systems with a caliber smaller than 100 mm, 132 armored vehicles, and 22 military planes on Crimean territory. It appears that Russia has used its military force in Crimea to ensure that its Naval Base will not be seized. Although, these troops did not have any Russian insignia in order to identify a chain of command, they are Russian citizens who wore military garb. Putin has stated that, “Russian forces in Crimea are only acting to protect Russian military assets. It is ‘citizens’ defense groups,’ not Russian forces, who have seized infrastructure and military facilities in Crimea.” If Putin ordered the Russian Forces in Crimea to seize Ukrainian infrastructure and military facilities, it would be intervention, but by stating they are citizens defense groups, it is a clever way to sidestep intervention. But intervention would be justified if Russia feels that its 1997 Partition Treaty is being threatened, which would allow Russia to preemptively neutralize Ukrainian military posts in Crimea before they can attack the naval base.

Protection of Citizens

As reported by Aljazeera, “Unhappy with the outcome of the protests in the capital and alarmed at the rise of Ukrainian nationalist groups in Kiev, many ethnic Russians in Crimea, who make up almost 60 percent of the population here, have been protesting and calling for Russia to come to their aid—with some even going as far as demanding their neighbor immediately absorb the territory.” International law does not allow for citizens to have the authority to call for intervention, but the intervening State may feel it has a duty to intervene and will unilaterally do so. It is, however, a point of contention as to the extent of the threat to ethnic Russians, or if there is any threat at all to warrant Russian intervention.

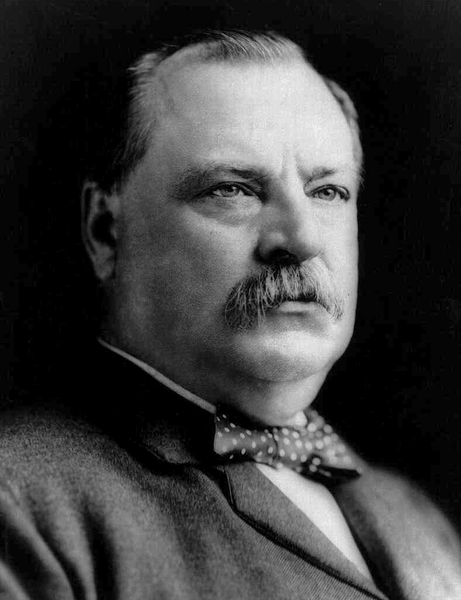

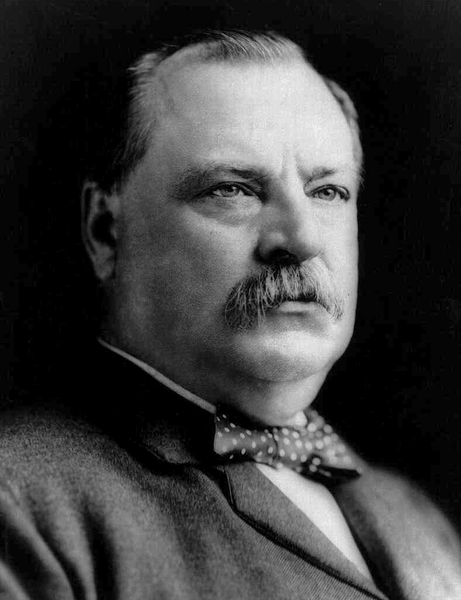

What is lacking in the Crimean conflict is an impartial investigation into the crisis where legally relevant facts could be gathered and conclusions made in accordance with international law. For the Hawaiian crisis in 1893, President Benjamin Harrison refused to do an investigation that was called for by Queen Lili‘uokalani, because he was intent on annexing the Hawaiian Kingdom for military purposes. It was his successor in office, Grover Cleveland, that did the investigation in accordance with international law. In his message to Congress, Cleveland stated,

“The law of nations is founded upon reason and justice, and the rules of conduct governing individual relations between citizens or subjects of a civilized state are equally applicable as between enlightened nations. The considerations that international law is without a court for its enforcement, and that obedience to its commands practically depends upon good faith, instead of upon the mandate of a superior tribunal, only give additional sanction to the law itself and brand any deliberate infraction of it not merely as a wrong but as a disgrace. A man of true honor protects the unwritten word which binds his conscience more scrupulously, if possible, than he does the bond a breach of which subjects him to legal liabilities; and the United States in aiming to maintain itself as one of the most enlightened of nations would do its citizens gross injustice if it applied to its international relations any other than a high standard of honor and morality. On that ground the United States can not properly be put in the position of countenancing a wrong after its commission any more than in that of consenting to it in advance. On that ground it can not allow itself to refuse to redress an injury inflicted through an abuse of power by officers clothed with its authority and wearing its uniform; and on the same ground, if a feeble but friendly state is in danger of being robbed of its independence and its sovereignty by a misuse of the name and power of the United States, the United States can not fail to vindicate its honor and its sense of justice by an earnest effort to make all possible reparation.”

“The law of nations is founded upon reason and justice, and the rules of conduct governing individual relations between citizens or subjects of a civilized state are equally applicable as between enlightened nations. The considerations that international law is without a court for its enforcement, and that obedience to its commands practically depends upon good faith, instead of upon the mandate of a superior tribunal, only give additional sanction to the law itself and brand any deliberate infraction of it not merely as a wrong but as a disgrace. A man of true honor protects the unwritten word which binds his conscience more scrupulously, if possible, than he does the bond a breach of which subjects him to legal liabilities; and the United States in aiming to maintain itself as one of the most enlightened of nations would do its citizens gross injustice if it applied to its international relations any other than a high standard of honor and morality. On that ground the United States can not properly be put in the position of countenancing a wrong after its commission any more than in that of consenting to it in advance. On that ground it can not allow itself to refuse to redress an injury inflicted through an abuse of power by officers clothed with its authority and wearing its uniform; and on the same ground, if a feeble but friendly state is in danger of being robbed of its independence and its sovereignty by a misuse of the name and power of the United States, the United States can not fail to vindicate its honor and its sense of justice by an earnest effort to make all possible reparation.”

“These principles apply to the present case with irresistible force when the special conditions of the Queen’s surrender of her sovereignty are recalled. She surrendered not to the provisional government, but to the United States. She surrendered not absolutely and permanently, but temporarily and conditionally until such time as the facts could be considered by the United States. Furthermore, the provisional government acquiesced in her surrender in that manner and on those terms, not only by tacit consent, but through the positive acts of some members of that government who urged her peaceable submission, not merely to avoid bloodshed, but because she could place implicit reliance upon the justice of the United States, and that the whole subject would be finally considered at Washington.”

According to international law there is a recognized legal maxim, ex injuria jus non oritur, whereby a State cannot claim valid legal results from an illegal act committed against another State. The International Court of Justice, in its Advisory Opinion on Namibia (June 21, 1971), explained, “the principle ex injuria jus non oritur dictates that acts which are contrary to international law cannot become a source of legal acts for the wrongdoer… To grant recognition to illegal acts or situation will tend to perpetuate it and be benefitial to the state which has acted illegally.”

United States Intervention in Hawai‘i and the Russian Intervention in Crimea

On March 4, 2014, CNN covered a speech by U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry in Kiev, Ukraine. Kerry stated, “They would have you believe that ethnic Russians and Russian bases are threatened. They would have you believe the Kiev was trying to destabilize Crimea or that Russian actions were legal or legitimate because Crimean leaders invited intervention. And as everybody knows the soldiers in Crimea, at the instruction of their government, had stood their ground, had never fired a shot, never issued one provocation.”

On March 4, 2014, CNN covered a speech by U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry in Kiev, Ukraine. Kerry stated, “They would have you believe that ethnic Russians and Russian bases are threatened. They would have you believe the Kiev was trying to destabilize Crimea or that Russian actions were legal or legitimate because Crimean leaders invited intervention. And as everybody knows the soldiers in Crimea, at the instruction of their government, had stood their ground, had never fired a shot, never issued one provocation.”

Kerry accused Russia of doing exactly what the United States did to the Hawaiian  Kingdom in January 1893. Unlike the Crimean dispute, however, the Hawaiian dispute was settled by U.S. President Grover Cleveland after he initiated an investigation into the overthrow of the Hawaiian government

Kingdom in January 1893. Unlike the Crimean dispute, however, the Hawaiian dispute was settled by U.S. President Grover Cleveland after he initiated an investigation into the overthrow of the Hawaiian government at the request of Queen Lili‘uokalani, Hawaiian Head of State, in March 1893. At the center of the investigation were the actions taken by U.S. Minister Plenipotentiary John Stevens

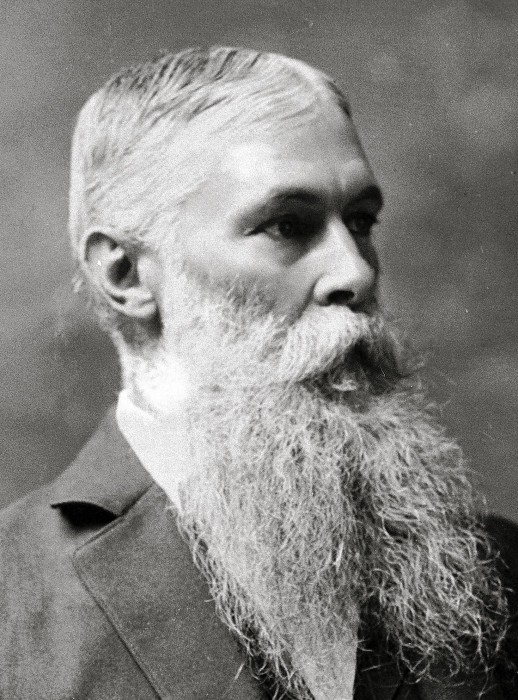

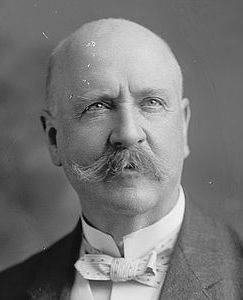

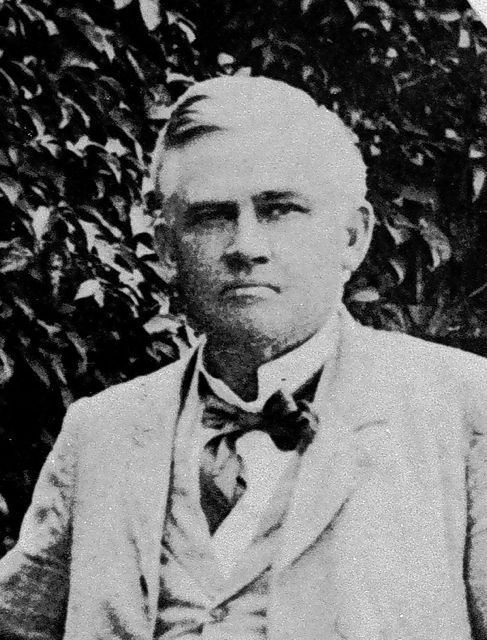

at the request of Queen Lili‘uokalani, Hawaiian Head of State, in March 1893. At the center of the investigation were the actions taken by U.S. Minister Plenipotentiary John Stevens  and the commander of U.S. troops aboard the U.S.S. Boston anchored in Honolulu Harbor, Captain Gilbert Wiltse. The intervention occurred during President Benjamin Harrison’s administration. The President appointed James Blount as Special Commissioner who submitted reports between April and July 1893 to U.S. Secretary of State Walter Gresham. The investigation was concluded by Gresham on October 18, 1893. President Cleveland notified the Congress of the conclusion of the investigation by presidential message on December 18, 1893, while negotiations were still taking place with the Queen in Honolulu.

and the commander of U.S. troops aboard the U.S.S. Boston anchored in Honolulu Harbor, Captain Gilbert Wiltse. The intervention occurred during President Benjamin Harrison’s administration. The President appointed James Blount as Special Commissioner who submitted reports between April and July 1893 to U.S. Secretary of State Walter Gresham. The investigation was concluded by Gresham on October 18, 1893. President Cleveland notified the Congress of the conclusion of the investigation by presidential message on December 18, 1893, while negotiations were still taking place with the Queen in Honolulu.

The investigation determined that the United States unlawfully intervened in the internal affairs of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and that its diplomat and troops were directly responsible for the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian government. Gresham recommended to President Cleveland that the Hawaiian government must be restored and compensation must be provided. This prompted executive mediation between President Cleveland and Queen Lili‘uokalani to settle the dispute and by exchange of notes an executive agreement, called the “Agreement of Restoration,” was concluded whereby the President committed to the restoration of the Hawaiian government and the Queen, thereafter, to grant amnesty to the insurgents. The President did not carry out the international agreement because of political wrangling in the Congress, and President Cleveland’s successor, William McKinley, unilaterally seized the Hawaiian Islands during the Spanish-American War on August 12, 1898. Hawai‘i has been under an illegal and prolonged occupation ever since.

Here follows Gresham’s report to President Cleveland regarding U.S. intervention in Hawai‘i that took place under President Benjamin Harrison’s administration.

Here follows Gresham’s report to President Cleveland regarding U.S. intervention in Hawai‘i that took place under President Benjamin Harrison’s administration.

Department of State,

Washington, October 18, 1893

The President:

The full and impartial reports submitted by the Hon. James H. Blount, your special commissioner to the Hawaiian Islands, established the following facts:

Queen Liliuokalani announced her intention on Saturday, January 14, 1893, to proclaim a new constitution, but the opposition of her ministers and other induced her to speedily change her purpose and make public announcement of that fact.

At a meeting in Honolulu, late on the afternoon of that day, a so-called committee of public safety, consisting of thirteen men, being all or nearly all who were present, was appointed “to consider the situation and devise ways and means for the maintenance of the public peace and the protection of life and property,” and at a meeting of this committee on the 15th, or the forenoon of the 16th of January, it was resolved amongst other things that a provisional government be created “to exist until terms of union with the United States of America have been negotiated and agreed upon.” At a mass meeting which assembled at 2 p.m. on the last named day, the Queen and her supporters were condemned and denounced, and the committee was continued and all its act approved.

Later the same afternoon the committee addressed a letter to John L. Stevens, the American minister at Honolulu, stating that the lives and property of the people were in peril and appealing to him and the United States forces at his command for assistance. This communication concluded “we are unable to protect ourselves without aid, and therefore hope for the protection of the United States forces.” On receipt of this letter Mr. Stevens requested

American minister at Honolulu, stating that the lives and property of the people were in peril and appealing to him and the United States forces at his command for assistance. This communication concluded “we are unable to protect ourselves without aid, and therefore hope for the protection of the United States forces.” On receipt of this letter Mr. Stevens requested  Capt. Wiltse, commander of the U.S.S. Boston, to land a force “for the protection of the United States legation, United States consulate, and to secure the safety of American life and property.” The well armed troops, accompanied by two gatling guns, were promptly landed and marched through the quiet streets of Honolulu to a public hall, previously secured by Mr. Stevens for their accommodation. This hall was just across the street form the government building, and in plain view of the Queen’s palace. The reason for thus locating the military will presently appear. The governor of the Island immediately addressed to Mr. Stevens a communication protesting against the act as an unwarranted invasion of Hawaiian soil and reminding him that the proper authorities had never denied permission to the naval forces of the United States to land for drill or any other proper purpose.

Capt. Wiltse, commander of the U.S.S. Boston, to land a force “for the protection of the United States legation, United States consulate, and to secure the safety of American life and property.” The well armed troops, accompanied by two gatling guns, were promptly landed and marched through the quiet streets of Honolulu to a public hall, previously secured by Mr. Stevens for their accommodation. This hall was just across the street form the government building, and in plain view of the Queen’s palace. The reason for thus locating the military will presently appear. The governor of the Island immediately addressed to Mr. Stevens a communication protesting against the act as an unwarranted invasion of Hawaiian soil and reminding him that the proper authorities had never denied permission to the naval forces of the United States to land for drill or any other proper purpose.

About the same time the Queen’s minister of foreign affairs sent a note to Mr. Stevens asking why the troops had been landed and informing him that the proper authorities were able and willing to afford full protection to the American legation and all American interests in Honolulu. Only evasive replies were sent to these communications.

While there were no manifestations of excitement or alarm in the city, and the people were ignorant of the contemplated movements, the committee entered the Government building, after first ascertaining that it was unguarded, and read a proclamation declaring that the existing Government was overthrown and a Provisional Government established in its place, “to exist until terms of union with the United States of America have been negotiated and agreed upon.” No audience was present when the proclamation was read, but during the reading 40 to 50 men, some of them indifferently armed, entered the room. The executive and advisory councils mentioned in the proclamation at once addressed a communication to Mr. Stevens, informing him that the monarchy had been abrogated and a provisional government established. This communication concluded:

Such Provisional Government has been proclaimed, is now in possession of the Government departmental buildings, the archives, and the treasury, and is in control of the city. We hereby request that you will, on behalf of the United States, recognize it as the existing de facto Government of the Hawaiian Islands and afford to it the moral support of your Government, and, if necessary, the support of American troops to assist in preserving the public peace.

On receipt of this communication, Mr. Stevens immediately recognized the new Government, and, in a letter addressed to Sanford B. Dole, its President, informed him that he had done so. Mr. Dole replied:

On receipt of this communication, Mr. Stevens immediately recognized the new Government, and, in a letter addressed to Sanford B. Dole, its President, informed him that he had done so. Mr. Dole replied:

Government Building,

Honolulu, January 17, 1893

Sir: I acknowledge receipt of your valued communication of this day, recognizing the Hawaiian Provisional Government, and express deep appreciation of the same.

We have conferred with the ministers of the late Government, and have made demand upon the marshal to surrender the station house. We are not actually yet in possession of the station house, but as night is approaching and our forces may be insufficient to maintain order, we request the immediate support of the United States forces, and would request that the commander of the United States forces take command of our military forces, so that they may act together for the protection of the city.

Respectfully, yours,

Sanford B. Dole,

Chaiman Executive Council.

His Excellency John L. Stevens,

United States Minister Resident.

Note of Mr. Stevens at the end of the above communication.

“The above request not complied with.”

Stevens.

The station house was occupied by a well armed force, under the command of a resolute capable, officer. The same afternoon the Queen, her ministers, representatives of the Provisional Government, and other held a conference at the palace. Refusing to recognize the new authority or surrender to it, she was informed that the Provisional Government had the support of the American minister, and, if necessary, would be maintained by the military force of the United States then present; that any demonstration on her part would precipitate a conflict with that force; that she could not, with hope of success, engage in war with the United States, and that resistance would result in a useless sacrifice of life. Mr. Damon, one of the chief leader of the movement, and afterwards vice-president of the Provisional Government, informed the Queen that she could surrender under protest and her case would be considered later at Washington. Believing that, under the circumstances, submission was a duty, and that her case would be fairly considered by the President of the United States, the Queen finally yielded and sent to the Provisional Government the paper, which reads:

“I, Lili‘uokalani, by the grace of God and under the constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Queen, do hereby solemnly protest against any and all acts done against myself and the constitutional Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom by certain persons claiming to have established a provisional government of and for this Kingdom.

That I yield to the superior force of the United States of America whose Minister Plenipotentiary, His Excellency John L. Stevens, has caused United States troops to be landed at Honolulu and declared that he would support the provisional government.

Now to avoid any collision of armed forces, and perhaps the loss of life, I do this under protest and impelled by said force yield my authority until such time as the Government of the United States shall, upon facts being presented to it, undo the action of its representatives and reinstate me in the authority which I claim as the Constitutional Sovereign of the Hawaiian Islands.”

When this paper was prepared at the conclusion of the conference, and signed by the Queen and her ministers, a number of persons, including one or more representatives of the Provisional Government, who were still present and understood its contents, by their silence, at least, acquiesced in its statements, and, when it was carried to President Dole, he indorsed upon it, “Received from the hands of the late cabinet this 17th day of January, 1893,” without challenging the truth of any of its assertions. Indeed, it was not claimed on the 17th day of January, or for some time thereafter, by any of the designated officers of the Provisional Government or any annexationist that the Queen surrendered otherwise than as stated in her protest.

In his dispatch to Mr. Foster of January 18, describing the so-called revolution, Mr. Stevens says:

The committee of public safety forthwith took possession of the Government building, archives, and treasury, and installed the Provisional Government at the head of the respective departments. This being an accomplished fact, I promptly recognized the Provisional Government as the de facto government of the Hawaiian Islands.

In Secretary Foster’s communication of February 15 to the President, laying before him the treaty of annexation, with the view to obtaining the advice and consent of the Senate thereto, he says:

At the time the Provisional Government took possession of the Government building no troops or officers of the United States were present or took any part whatever in the proceedings. No public recognition was accorded to the Provisional Government by the United States minister until after the Queen’s abdication, and when they were in effective possession of the Government building, the archives, the treasury, the barracks, the police station, and all the potential machinery of the Government.

Similar language is found in an official letter addressed to Secretary Foster on February 3 by the special commissioners sent to Washington by the Provisional Government to negotiate a treaty of annexation.

These statements are utterly at variance with the evidence, documentary and oral, contained in Mr. Blount’s reports. They are contradicted by declarations and letters of President Dole and other annexationists and by Mr. Stevens’s own verbal admissions to Mr. Blount. The Provisional Government was recognized when it had little other than a paper existence, and when the legitimate government was in full possession and control of the palace, the barracks, and the police station. Mr. Stevens’s well known hostility and the threatening presence of the force landed from the Boston was all that could then have excited serious apprehension in the minds of the Queen, her officers, and loyal supporters.

It is fair to say that Secretary Foster’s statements were based upon information which he had received from Mr. Stevens and the special commissioners, but I am unable to see that they were deceived. The troops were landed, not to protect American life and property, but to aid in overthrowing the existing government. Their very presence implied coercive measures against it.

In a statement given to Mr. Blount, by Admiral Skerret, the ranking naval officer at Honolulu, he says:

“If the troops were landed simply to protect American citizens and interests, they were badly stationed in Arion Hall, but if the intention was to aid the Provisional Government they were wisely stationed.”

This hall was so situated that the troops in it easily commanded the Government building, and the proclamation was real under the protection of American guns. At an early stage of the movement, if not at the beginning, Mr. Stevens promised the annexationists that as soon as they obtained possession of the Government building and there read a proclamation of the character above referred to, he would at once recognize them as a de facto government, and support them by landing a force from our war ship then in the harbor, and he kept that promise. This assurance was the inspiration on the movement, and without it the annexationists would not have exposed themselves to the consequences of failure. They relied upon no military force of their own, for they had none worthy of the name. The Provisional Government was established by the action of the American minister and the presence of the troops landed from the Boston, and its continued existence is due to the belief of the Hawaiians that if they made an effort to overthrow it, they would encounter the armed forces of the United States.

The earnest appeals to the American minister for military protection by the officers of that Government, after it had been recognized, show the utter absurdity of the claim that it was established by a successful revolution of the people of the Islands. Those appeals were a confession by the men who made them of their weakness and timidity. Courageous men, conscious of their strength and the justice of their cause, do not thus act. It is not now claimed that a majority of the people, having the right to vote under the constitution of 1887, ever favored the existing authority or annexation to this or any other country. They earnestly desire that the government of their choice shall be restored and its independence respected.

Mr. Blount states that while at Honolulu he did not meet a single annexationist who expressed willingness to submit the question to a vote of the people, nor did he talk with one on that subject who did not insist that if the Islands were annexed suffrage should be so restricted as to give complete control to foreigners or whites. Representative annexationists have repeatedly made similar statements to the undersigned.

The Government of Hawaii surrendered its authority under a threat of war, until such time only as the Government of the United States, upon the facts being presented to it, should reinstate the constitutional sovereign, and the Provisional Government was created “to exist until terms of union with the United States of America have been negotiated and agreed upon.” A careful consideration of the fact will, I think, convince you that the treaty which was withdrawn from the Senate for further consideration should not be resubmitted for its action thereon.

Should not the great wrong done to a feeble but independent State by an abuse of the authority of the United States be undone by restoring the legitimate government? Anything short of that will not, I respectfully submit, satisfy the demands of justice.

Can the United States consistently insist that other nations shall respect the independence of Hawaii while not respecting it themselves? Our Government was the first to recognize the independence of the Islands and it should be the last to acquire sovereignty over them by force and fraud.

Respectfully submitted.

W.Q. Gresham.

Hawaiian Neutrality and the Crimean Conflict

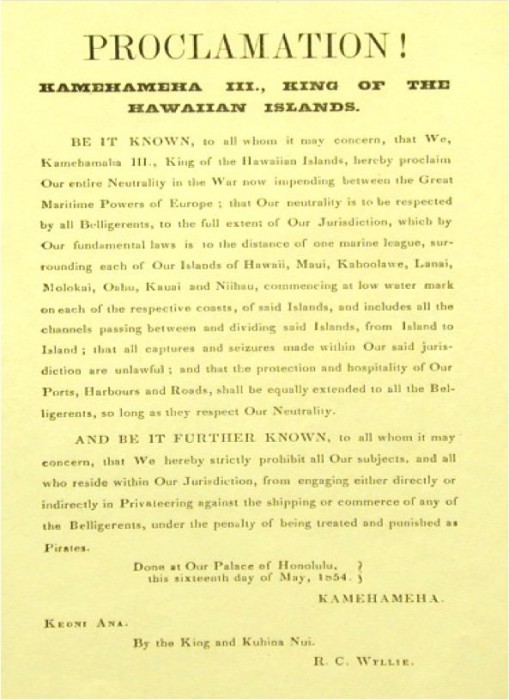

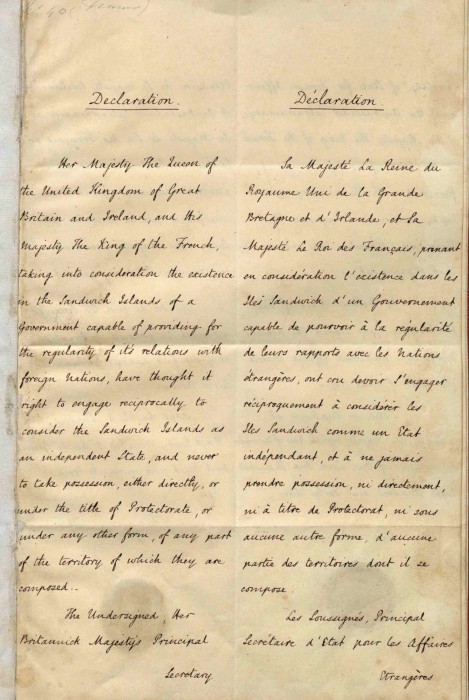

With the world’s attention on Russia and the Crimean Peninsula, people may not know that the Hawaiian Kingdom’s neutrality was prompted by hostilities that erupted between Russia and the European Powers during the Crimean War (1854-56). The Hawaiian Kingdom was also an active participant during the war in the development of the international laws on neutrality.

Russia’s Black Sea Naval Fleet is based at Sevastopol Naval Base in Crimea, which gives Russian naval vessels access to the Mediterranean and Aegean Seas, and further to the Atlantic Ocean. The two waterways that provide access from the Black Sea are Turkey’s Bosporus Straits and the Strait of the Dardanelles. Sevastopol Naval Base was also at the center of a war between Russia and the Ottoman Empire in 1853 over this access after Russia insisted that the Ottoman Turks recognize Russia’s right in the Middle East in order to protect Russian Orthodox in the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman’s refused and war broke out. On March 28, 1854, France and Great Britain joined the war on the side of the Ottoman Turks in order to prevent Russia’s increase in power over the region.

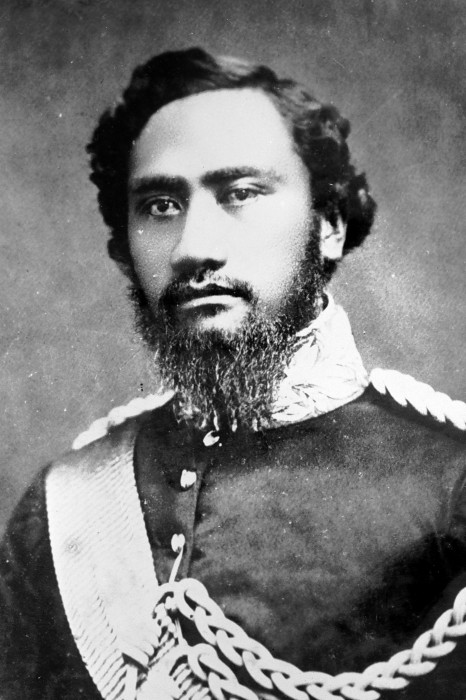

Naval battles between Russia and the French and British also spilled over to the Pacific Ocean where all three countries had naval and merchant ships. Battles were not confined to Crimea and the Caucasus, but were also fought in the Japan Seas, the Okhotsk Seas and in the North Pacific Ocean, and there was concern in Hawai‘i that it could reach the Hawaiian Islands. Just eleven years since Great Britain and France recognized the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State, King Kamehameha III, in Privy Council, declared the Hawaiian Kingdom to be a neutral State on May 16, 1854.

Naval battles between Russia and the French and British also spilled over to the Pacific Ocean where all three countries had naval and merchant ships. Battles were not confined to Crimea and the Caucasus, but were also fought in the Japan Seas, the Okhotsk Seas and in the North Pacific Ocean, and there was concern in Hawai‘i that it could reach the Hawaiian Islands. Just eleven years since Great Britain and France recognized the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State, King Kamehameha III, in Privy Council, declared the Hawaiian Kingdom to be a neutral State on May 16, 1854.

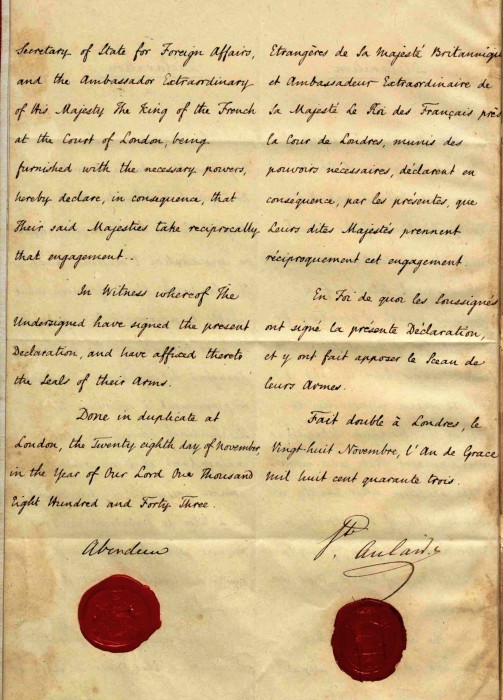

Prior to their impending involvement in the Crimean War, Great Britain and France each issued formal Declarations on March 28, 1854, and March 29, 1854, that declared neutral ships and goods would not be captured. Prior to this, international law did not afford protection for neutral ships carrying goods headed for the ports of countries who were at war. Under international law, these ships could be seized by either country’s naval vessels or by private ships that were commissioned by a country at war, which is called “privateering” and the goods seized were called “prizes.” The British and French diplomats that were posted in the Hawaiian Kingdom delivered both Declarations to the Hawaiian government.

On June 15, 1854, the Hawaiian Committee on the National Rights in regards to prizes had delivered its report during a meeting of the Privy Council in Honolulu. Robert C. Wyllie, Hawaiian Minister of Foreign Affairs, presented the committee report and the following resolution was passed and later made known to the countries engaged in the Crimean War.

On June 15, 1854, the Hawaiian Committee on the National Rights in regards to prizes had delivered its report during a meeting of the Privy Council in Honolulu. Robert C. Wyllie, Hawaiian Minister of Foreign Affairs, presented the committee report and the following resolution was passed and later made known to the countries engaged in the Crimean War.

“Resolved: That in the Ports of this neutral Kingdom, the privilege of Asylum is extended equally and impartially to the armed national vessels and prizes made by such vessels of all the belligerents, but no authority can be delegated by any of the Belligerents to try and declare lawful and transfer the property of such prizes within the King’s Jurisdiction; nor can the King’s Tribunals exercise any such jurisdiction, except in cases where His Majesty’s Neutral Jurisdiction and Sovereignty may have been violated by the Captain of any vessel within the bounds of that Jurisdiction.”

To broaden the international law of neutrality, the United States sought to get countries to agree thereby creating customary international law. On December 6, 1854, the U.S. diplomat assigned to the Hawaiian Kingdom, David L. Gregg, sent the following dispatch to the Hawaiian government regarding the recognition of neutral rights. The correspondence stated,

“I have the honor to transmit to you a project of a declaration in relation to neutral rights which my Government has instructed me to submit to the consideration of the Government of Hawaii, and respectfully to request its approval and adoption. As you will perceive it affirms the principles that free ships make free goods, and that the property of neutrals, not contraband of war, found on board of Enemies ships, is not confiscable. These two principles have been adopted by Great Britain and France as rules of conduct towards all neutrals in the present European war; and it is pronounced that neither nation will refuse to recognize them as rules of international law, and to conform to them in all time to come. The Emperor of Russia has lately concluded a convention with the United States, embracing these principles as permanent, and immutable, and to be scrupulously observed towards all powers which accede to the same.”

On January 12, 1855, the U.S. diplomat also sent another dispatch to the Hawaiian government that contained a copy of the July 22, 1854 Convention between the United States of America and Russia embracing certain principles in regard to neutral rights. After careful review of the U.S. President’s request, King Kamehameha IV in Privy Council, passed the following resolution on March 26, 1855.

On January 12, 1855, the U.S. diplomat also sent another dispatch to the Hawaiian government that contained a copy of the July 22, 1854 Convention between the United States of America and Russia embracing certain principles in regard to neutral rights. After careful review of the U.S. President’s request, King Kamehameha IV in Privy Council, passed the following resolution on March 26, 1855.