As a State of Hawai‘i government agency, the Office of Hawaiian Affairs comes under the Sunshine Law. The purpose of the sunshine law is to provide public input and oversight for board and commission meetings of the State of Hawai‘i government. The State of Hawai‘i Office of Information Practices (OIP) oversees compliance to the Sunshine Law, which is a criminal statute.

According to the OIP Guide to the Sunshine Law for State and County Boards, “the intent of the Sunshine Law is to open up governmental processes to public scrutiny and participation by requiring state and county boards to conduct their business as openly as possible. The Legislature expressly declared that ‘it is the policy of this State that the formation and conduct of public policy—the discussions, deliberation, decisions, and actions of governmental agencies—shall be conducted as openly as possible.’”

All meetings of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs Board of Trustees (BOT) must be open to the public and the BOT must accept testimony, both written and oral, at its meetings. The BOT, however, can hold meetings that are not open to the public, which are called “executive meetings.” Executive meetings can only be convened for eight reasons: licensee information, personnel decisions, labor negotiations/public property acquisition, consult with Board’s attorney, investigate criminal misconduct, public safety/security, private donations, and State/Federal law or court order.

The OIP Guide states, that in order to “convene an executive meeting, a board must vote to do so in an open meeting and must publicly announce the purpose of the executive meeting. Two-thirds of the board members present must vote in favor of holding the executive meeting, and the members voting in favor must also make up a majority of all board members, including members not present at the meeting or membership slots not currently filled. The minutes of the open meeting must reflect the vote of each board member on the question of closing the meeting to the public.”

The BOT, however, could hold an “emergency meeting” that does not require notification with the Lieutenant Governor’s office and agenda only if there’s “an imminent peril to the public health, safety, or welfare.”

The OIC Guide states, “A willful violation of the Sunshine Law is a misdemeanor and, upon conviction, may result in the person being removed from the board. The Attorney General and the country prosecutor have the power to enforce any violations of the statute.”

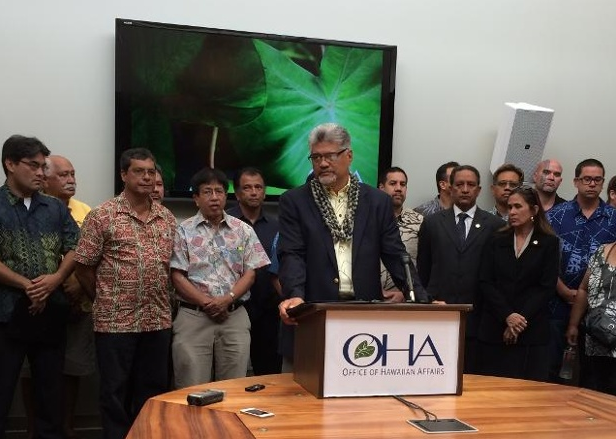

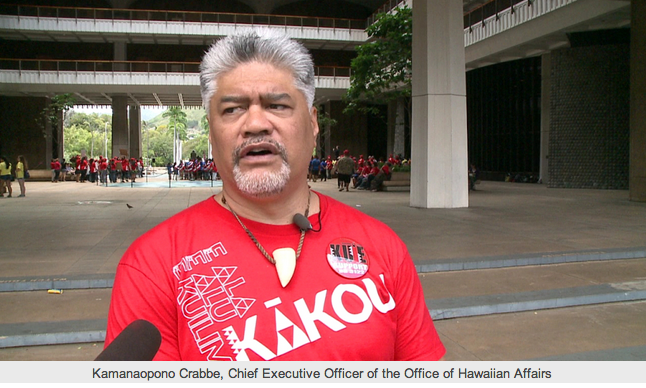

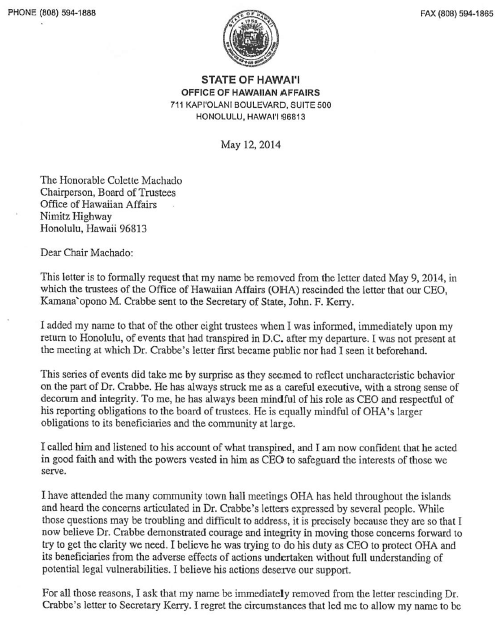

As reported by Larry Geller of the Disappeared News.com, there is no evidence that the BOT complied with the Sunshine Law and that the BOT’s meeting in Washington, D.C., where the Trustees voted to rescind the CEO Dr. Kamana‘opono Crabbe’s letter to Secretary of State Kerry, was held in secret. Information is now surfacing that there was no meeting of the BOT in Washington, D.C., and consequently if there was no meeting then there could have been no votes. The only evidence to confirm that a meeting was held is to have minutes of the meeting that would signify each of the Trustee’s votes and the discussion that preceded it. Furthermore, in order for this meeting to be in compliance with the Sunshine Law, the Lieutenant Governor’s office was supposed to have been notified six days in advance with the agenda for the meeting that was supposed to have been open to the public. But the Lieutenant Governor’s office has no record that any meeting took place in the month of May.

If there was to be a meeting, which we know there wasn’t, the Chairperson of the BOT could have convened an “special meeting” in Washington, D.C., where there existed an unanticipated event that requires a board to take immediate action. On this matter, the OIC Guide states that a “board may convene a special meeting with less than six calendar days’ notice because of an unanticipated event when a board must take action or a matter over which it has supervision, control, jurisdiction, or advisory power.” However, as confirmed by Mr. Gellar of Disappeared News.com, the Lieutenant Governor’s office has no record that notice of the May 9, 2014 BOT meeting was filed, thereby signaling a clear violation of the Sunshine Law and calling into question the validity of the May 9, 2014 BOT meeting and all actions allegedly discussed and voted on by the BOT.

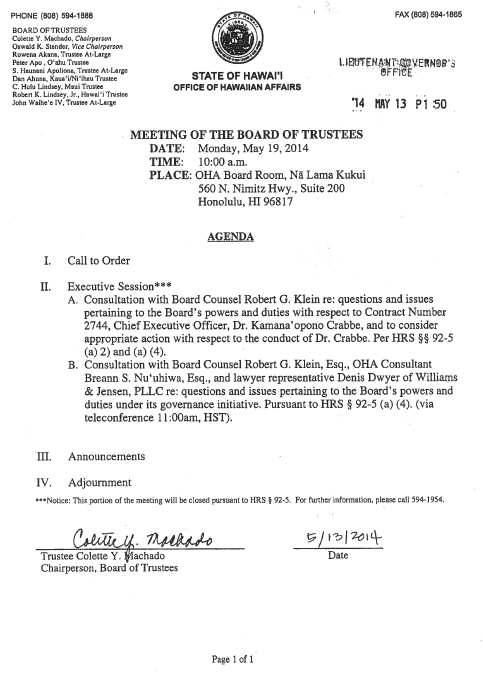

On May 13, 2014, the Lieutenant Governor’s office received a request from OHA Trustee Colette Y. Machado, Chairperson, Board of Trustees announcing an “Executive Session” meeting of the BOT for Monday, May 19, 2014, to “consider appropriate action with respect to the conduct of Dr. Crabbe,” and “questions and issues pertaining to the Board’s powers and duties under its governance initiate.” This is an executive meeting not open to the public.

The glaring problem with having this closed “executive meeting” is that it required an open “meeting” first. According to the Sunshine Law, “two-thirds of the board members present must vote in favor of holding the executive meeting, and the members voting in favor must also make up a majority of all board members,” and that “the minutes of the open meeting must reflect the vote of each board member on the question of closing the meeting to the public.” If there was no open meeting in Washington, D.C., to begin with, how could Trustee Chairwoman Colette Machado call for an “executive meeting” without first having a open meeting? Simply answered, she can’t because there was never a meeting to begin with.

Further complicating this issue for the BOT is that the Sunshine Law was directly addressed in an open meeting at the Office of Hawaiian Affairs on January 13, 2014. The issues centered on the commercial development of Kaka‘ako and whether or not actions taken by the Board violated the Sunshine Law. Former Associate Justice of the Hawai‘i Supreme Court and now BOT Counsel, Robert Klein, made the following statement to the Board’s open meeting of the Committee on Beneficiary Advocacy and Empowerment, which are reflected in the minutes. All nine of the Trustees were present.

Minutes of January 13, 2014:

Board Counsel Klein shares that there are a few exceptions. We operate on the principle that if you have two trustees, you’re fairly safe in not filing agendas for meetings between the two. The whole point of the sunshine law is to give notice to the public; if you’re having something that resembles a meeting (a quorum of Trustees that are meeting about anything).

Board Counsel Klein shares that there are a few exceptions. We operate on the principle that if you have two trustees, you’re fairly safe in not filing agendas for meetings between the two. The whole point of the sunshine law is to give notice to the public; if you’re having something that resembles a meeting (a quorum of Trustees that are meeting about anything).

In the case where you have two trustees who are meeting, in most situations that is way short of a quorum. Whatever they’re discussing, as long as they’re not trading votes or making arrangements on a certain issue, you’re not going to run afoul of the sunshine law.

When you get to three trustees, you need a special exemption. Many boards and commissions have 5 members, so when you have 3 together, you have quorum. However, this is a large board where there are 9 of you, so you don’t have a quorum until there are 5 you; so 3 is a safe number. The question is whether you can find an exception in the sunshine law for 3 trustees to meet together and when you look at the sunshine law there are certain exceptions called “Permitted Interactions” and what that means is you can have interactions with 2 or more trustees short of a quorum as long as you’re not trading votes and deciding things away from the public eye.

Under these circumstances the legislature has provided for exceptions. In this situation, the only exception that potentially applies is the exception where two or more but less than a quorum of trustees meet to discuss or negotiate a point that the trustees as a whole in public have already agreed to be the position of OHA and that commission or committee of the Board is moving forward running with the proposal already approved in public by the trustees.

Trustee Chairwoman Machado cannot claim ignorance of the Sunshine Law and nor can all nine of the Trustees. The actions taken by the Board in Washington, D.C., clearly was in violation of the Sunshine Law. The irony of the whole situation is that the May 9 letter to Secretary of State Kerry attempting to rescind the CEO’s letter of inquiry, which has all nine signatures of the Trustees, is the evidence of the violation of the Sunshine Law. As such, this would consequently render the Trustees’ letter to Secretary of State Kerry “void” because it stemmed from a direct violation of the law itself.

Trustee Chairwoman Machado cannot claim ignorance of the Sunshine Law and nor can all nine of the Trustees. The actions taken by the Board in Washington, D.C., clearly was in violation of the Sunshine Law. The irony of the whole situation is that the May 9 letter to Secretary of State Kerry attempting to rescind the CEO’s letter of inquiry, which has all nine signatures of the Trustees, is the evidence of the violation of the Sunshine Law. As such, this would consequently render the Trustees’ letter to Secretary of State Kerry “void” because it stemmed from a direct violation of the law itself.

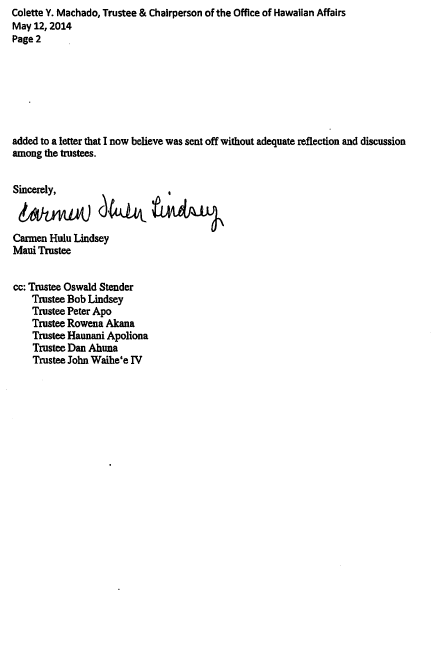

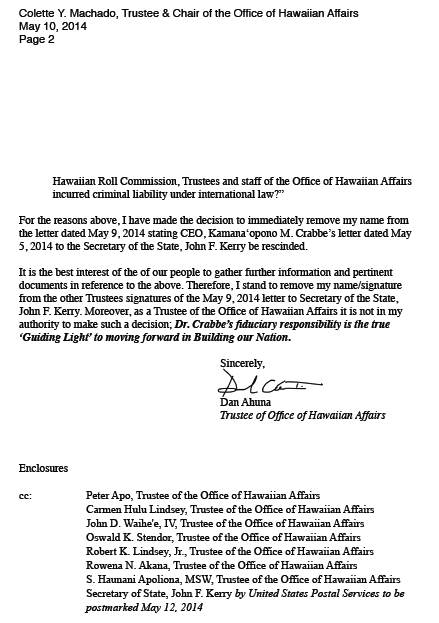

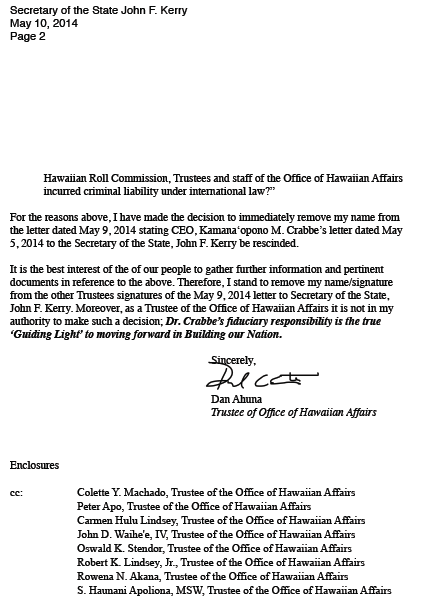

Trustees Dan Ahuna and Hulu Lindsey took the right steps in removing their names from the May 9, 2014 rescinding letter because it shows that there was no “willful violation of the Sunshine Law,” which is a misdemeanor, on their part. It would make sense for all of the Trustees to follow their example before its too late.

CORRECTION: It was incorrectly stated that the meeting scheduled for Monday, May 19, 2014, was an executive meeting closed to the public. The meeting is an open meeting, but a portion of the meeting would be closed to the public. Since the closed meeting is an extension of the original violation of the Sunshine Law that took place in Washington, D.C., the Monday meeting is illegal.