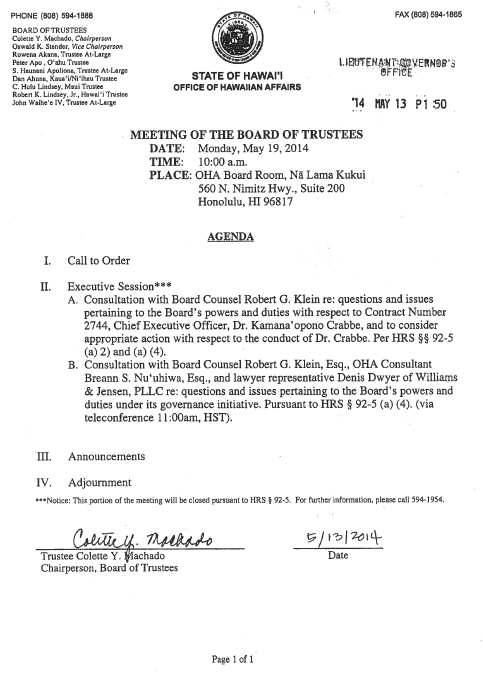

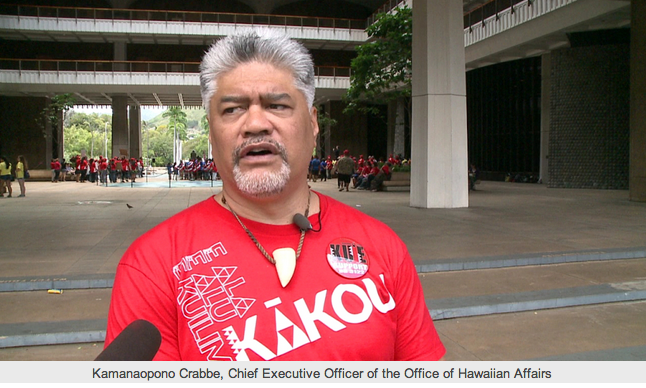

It has been nearly a month since the Office of Hawaiian Affairs (OHA) CEO Dr. Kamana‘opono Crabbe posed four questions to Secretary of State Kerry in a letter dated May 5, 2014.

It has been nearly a month since the Office of Hawaiian Affairs (OHA) CEO Dr. Kamana‘opono Crabbe posed four questions to Secretary of State Kerry in a letter dated May 5, 2014.

- First, does the Hawaiian Kingdom, as a sovereign independent State, continue to exist as a subject of international law?

- Second, if the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist, do the sole-executive agreements bind the United States today?

- Third, if the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist and the sole-executive agreements are binding on the United States, what effect would such a conclusion have on United States domestic legislation, such as the Hawai‘i Statehood Act, 73 Stat. 4, and Act 195?

- Fourth, if the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist and the sole-executive agreements are binding on the United States, have the members of the Native Hawaiian Roll Commission, Trustees and staff of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs incurred criminal liability under international law?

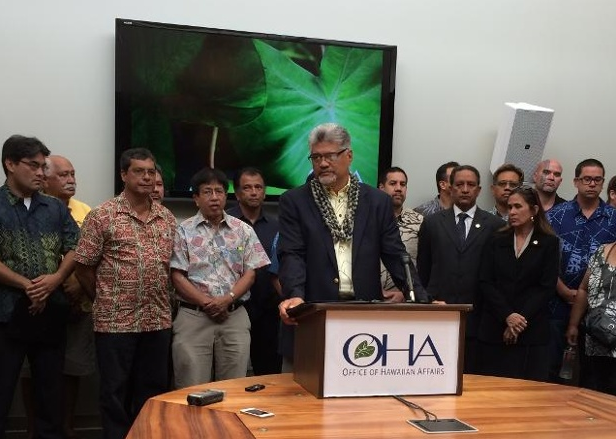

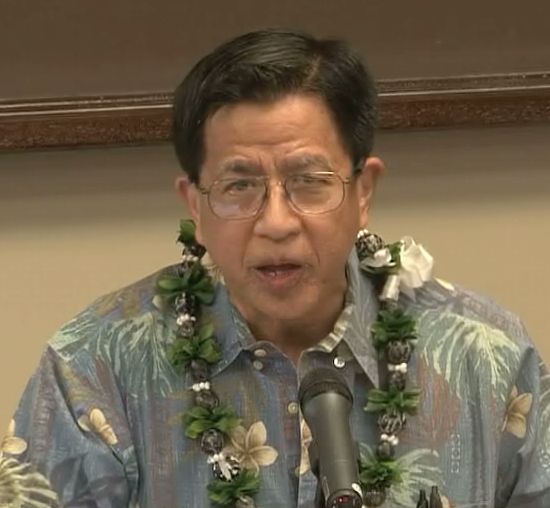

These questions centered on the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom and generated so much attention that it has awakened a sleeping giant—the Hawaiian community. Academics and professionals that stood shoulder to shoulder behind Dr. Crabbe at his  press conference on May 12, 2014 showed their solidarity and support. One of these individuals who stood directly behind Dr. Crabbe was Professor Williamson Chang, senior law professor at the University of Hawai‘i Richardson School of Law. In a Star-Advertiser article, Professor Chang described the letter as “a profound and important moment in history.” “He has raised an issue that has not been approached before. It’s remarkable that a state agency is asking these questions,” he said.

press conference on May 12, 2014 showed their solidarity and support. One of these individuals who stood directly behind Dr. Crabbe was Professor Williamson Chang, senior law professor at the University of Hawai‘i Richardson School of Law. In a Star-Advertiser article, Professor Chang described the letter as “a profound and important moment in history.” “He has raised an issue that has not been approached before. It’s remarkable that a state agency is asking these questions,” he said.

What has replaced the rhetoric of politicians and sovereignty activists that often distorts Hawaiian history and law has been replaced by historical accuracy and legal sophistication. Academics armed with Ph.D.’s have begun to address Hawai‘i’s revisionist history that became institutionalized since the American occupation began in 1898, and attorneys have begun to apply this information in the courts throughout Hawai‘i.

From an international law perspective, these questions were cleverly worded and organized and are grounded in the recognized principle of international law called the presumption of continuity of an established sovereign State, which is similar to the principle of presumption of innocence. An assumption is a conclusion “without” facts and a presumption is a conclusion “with” facts. So when a person is accused of committing a crime that person is presumed to be innocent until proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt because of the fact that the accused has legal rights. In international law, an established sovereign State is presumed to continue to exist because of the fact that it has legal rights, until evidence can be shown by another State that it has extinguished the sovereignty of the former State.

In 2001, the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Netherlands verified the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, 119 Int’l L. Rep. 566, 581 (2001) . The Court stated in its arbitration award, “in the nineteenth century the Hawaiian Kingdom existed as an independent State recognized as such by the United States of America, the United Kingdom and various other States, including by exchanges of diplomatic or consular representatives and the conclusion of treaties.” As an established State under international law since the nineteenth century, the Hawaiian Kingdom has these legal rights that apply to all States:

- States are judicially equal;

- Each State enjoys the rights inherent in full sovereignty;

- Each State has the duty to respect the personality of other States;

- The territorial integrity and political independence of the State are inviolable;

- Each State has the right freely to choose and develop its own political, social, economic and cultural systems; and

- Each State has the duty to comply fully and in good faith with its international obligations and to live in peace with other States.

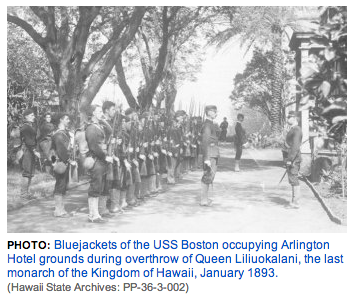

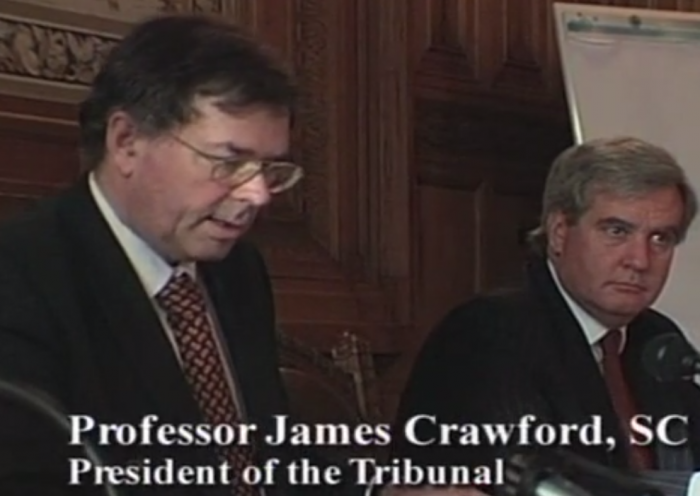

According to Professor Crawford, The Creation of States in International Law (2006), p. 34, who is not only the leading authority on States, but was also the presiding arbitrator in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, “There is a strong presumption that the State continues to exist, with its rights and obligations, despite revolutionary changes in government, or despite a period in which there is no, or no effective, government. Belligerent occupation does not affect the continuity of the State, even where there exists no government claiming to represent the occupied State.” So despite the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government by the United States on January 17, 1893, and the prolonged occupation since the Spanish-American War in 1898, the Hawaiian Kingdom, as a State, would continue to exist even if there was no Hawaiian government.

According to Professor Crawford, The Creation of States in International Law (2006), p. 34, who is not only the leading authority on States, but was also the presiding arbitrator in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, “There is a strong presumption that the State continues to exist, with its rights and obligations, despite revolutionary changes in government, or despite a period in which there is no, or no effective, government. Belligerent occupation does not affect the continuity of the State, even where there exists no government claiming to represent the occupied State.” So despite the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government by the United States on January 17, 1893, and the prolonged occupation since the Spanish-American War in 1898, the Hawaiian Kingdom, as a State, would continue to exist even if there was no Hawaiian government.

The presumption of continuity places the burden on the United States to show legally relevant facts that the Hawaiian Kingdom does not continue to exist under international law. In other words, the Hawaiian Kingdom does not have to prove its own existence because it is presumed to continue to exist, just as a person does not have to prove their innocence. To effectively remove the presumption of continuity, there must be uncontroverted evidence of the extinguishment of the Hawaiian Kingdom by the United States. Since the Hawaiian Kingdom has legal rights under international law, the United States will have to provide evidence of extinguishment that only international law recognizes. According to Article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice, the following sources of international law, ranked in order of precedence, are:

- International conventions (treaties), whether general or particular;

- International custom, as evidence of a general practice accepted as law;

- The general principles of law recognized by civilized nations; and

- Judicial decisions and the teachings of the most highly qualified publicists of the various nations, as subsidiary means for the determination of rules of law.

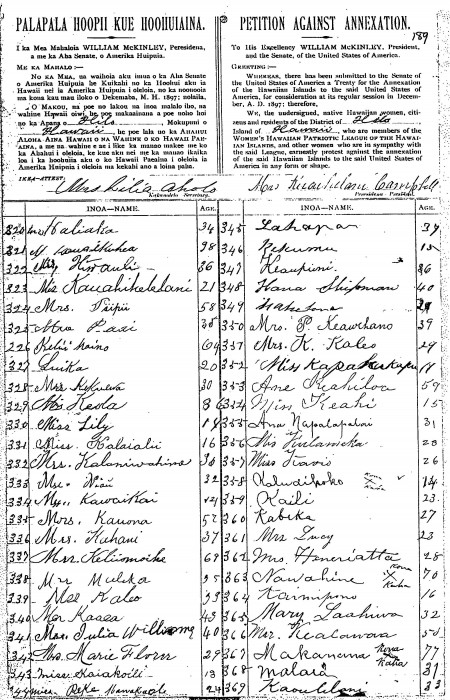

Under international law, a State who claims to be the successor of another State, when not at war, must take place by cession. Professor Oppenheim, International Law (1948), p. 499, explains that, “cession of State territory is the transfer of sovereignty over State territory by the owner-State to another State.” He further points out that the “only form in which a cession can be effected is an agreement embodied in a treaty between the ceding and the acquiring State.” The United States only claim to have extinguished the Hawaiian Kingdom is by a joint resolution of annexation passed by its Congress.

A joint resolution, however, is not a treaty or agreement between two states, but rather an agreement between the House of Representatives and the Senate in Washington, D.C. A joint resolution is a municipal law of the United States whose effect is limited to United States territory. The United States Supreme Court, The Apollon, 22 U.S. 362, 370 (1824), affirmatively stated, that the “laws of no nation can justly extend beyond its own territory” for it would be “at variance with the independence and sovereignty of foreign nations” In U.S. v. Belmont, 301 U.S. 324, 332 (1937), the Court also stated that, “our Constitution, laws and policies have no extraterritorial operation.”

Further complicating the problem for the United States was a legal opinion by the United States Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel in 1988. In the 1988 memorandum titled “Legal Issues Raised by Proposed Presidential Proclamation To Extend the Territorial Sea,” the Office of Legal Counsel addressed the annexation of the  Hawaiian Islands by joint resolution. Douglas Kmiec, Acting Assistant Attorney General, authored the memorandum for Abraham D. Sofaer, legal advisor to the U.S. State Department. After covering the limitation of Congressional authority and the objections made by members of the Congress, Kmiec concluded, “Notwithstanding these constitutional objections, Congress approved the joint resolution and President McKinley signed the measure in 1898. Nevertheless, whether this action demonstrates the constitutional power of Congress to acquire territory is certainly questionable. … It is therefore unclear which constitutional power Congress exercised when it acquired Hawaii by joint resolution. Accordingly, it is doubtful that the acquisition of Hawaii can serve as an appropriate precedent for a congressional assertion of sovereignty over an extended territorial sea.”

Hawaiian Islands by joint resolution. Douglas Kmiec, Acting Assistant Attorney General, authored the memorandum for Abraham D. Sofaer, legal advisor to the U.S. State Department. After covering the limitation of Congressional authority and the objections made by members of the Congress, Kmiec concluded, “Notwithstanding these constitutional objections, Congress approved the joint resolution and President McKinley signed the measure in 1898. Nevertheless, whether this action demonstrates the constitutional power of Congress to acquire territory is certainly questionable. … It is therefore unclear which constitutional power Congress exercised when it acquired Hawaii by joint resolution. Accordingly, it is doubtful that the acquisition of Hawaii can serve as an appropriate precedent for a congressional assertion of sovereignty over an extended territorial sea.”

Sovereignty of an established State is never in abeyance or in suspension. The sovereignty is either vested in the Hawaiian State itself or in the United States as its successor. If the Attorney General’s Office of Legal Counsel is “unclear” as to the authority of Congress, it cannot be considered to have extinguished the Hawaiian Kingdom’s continuity under international law, and, therefore, the presumption of continuity would remain with the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent sovereign State.

So when we revisit Dr. Crabbe’s letter and his questions posed to Secretary of State Kerry there is only the first question that would need to be answered with clear and convincing evidence that the Hawaiian State no longer exists under international law. But to do so, the United States would need to provide evidence of a treaty of annexation or an international custom that has terminated the Hawaiian State, which it doesn’t have. In other words, Dr. Crabbe’s questions were really rhetorical questions that he already knew the answers to. The significance of the letter, however, is that it was a formal notification of a State of Hawai‘i government official to the Secretary of State that OHA is aware that the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist and that it will have to deal with issues of criminal liability under international law.