Category Archives: National

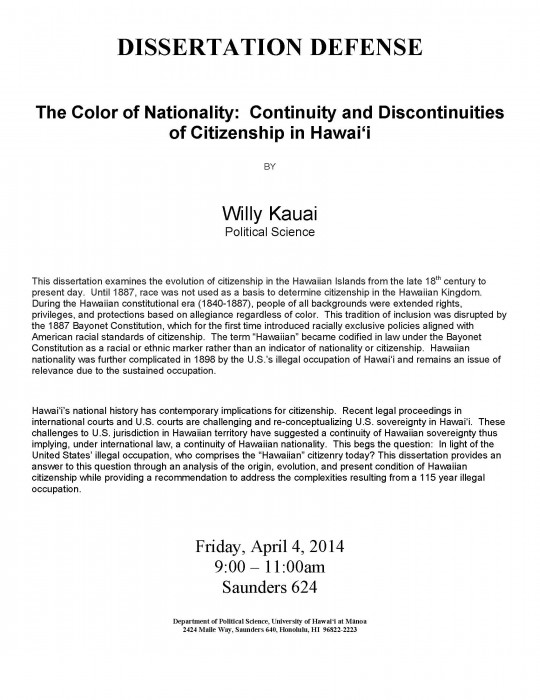

“Hawaiian Nationality” Dissertation Defense – Willy Kauai, Ph.D. candidate

***UPDATE. Willy Kauai successfully defended his dissertation. He will be graduating in May 2014 with a Ph.D. in political science. His committee members were comprised of Professor Neal Milner, Chair, Professor Debora Halbert, Professor Charles Lawrence III, Dr. Keanu Sai, Professor Melody Kapilialoha MacKenzie, and Professor Puakea Nogelmeier.

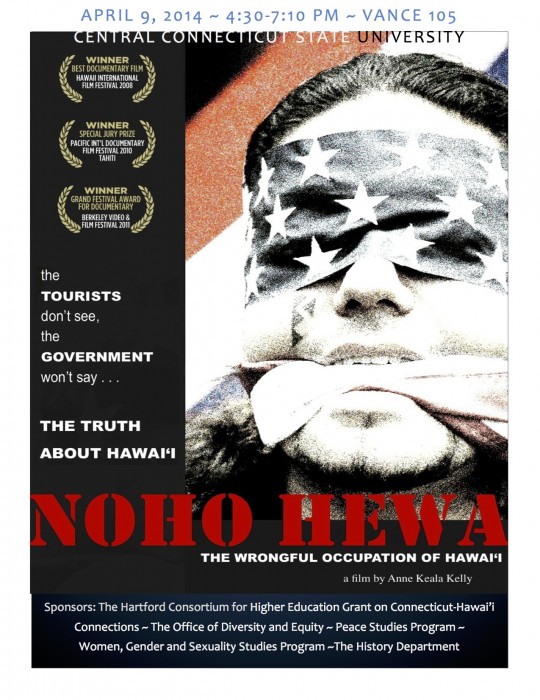

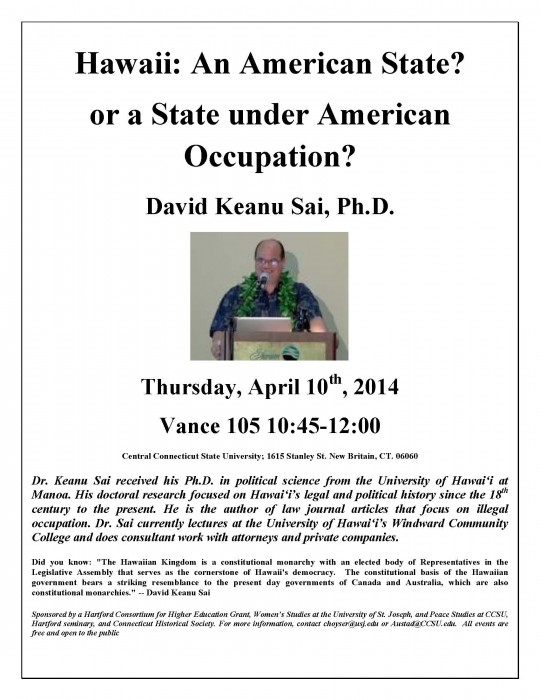

Dr. Keanu Sai to Present at Central Connecticut State University (CCSU) April 10th

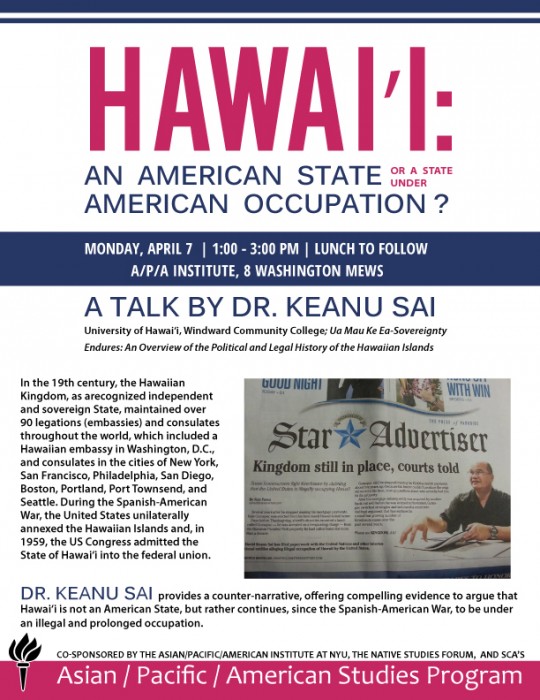

Dr. Keanu Sai to Present at New York University (NYU) April 7th

Hawai‘i and the Namibia Exception

According to international law, the United States Federal government and the United States’ State of Hawai‘i government operating within the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom are illegal regimes. Article 43 of the Hague Convention, IV, mandates that the occupying State, the United States, to administer the laws of the occupied State, the Hawaiian Kingdom. According to Professor Marco Sassoli, Article 43 of the Hague Regulations and Peace Operations in the Twenty-first Century, p. 5, “Article 43 does not confer on the occupying power any sovereignty over the occupied territory. The occupant may therefore not extend its own legislation over the occupied territory nor act as a sovereign legislator. It must, as a matter of principle, respect the laws in force in the occupied territory at the beginning of the occupation.”

These illegal regimes are and have been administering United States law and not Hawaiian law in an attempt to conceal the prolonged and illegal occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom. According to Dr. Yaël Ronen, Status of Settlers Implanted by Illegal Regimes under International Law (2008), p. 2, “Illegal regimes often transfer of their own populations or populations loyal to them in the territory, and subsequently grant these populations residence or nationality in the territory. This is done in order to change the demographic composition of the territory under dispute and thereby solidify the regime.”

When another country’s government is operating within the territory of another country without title or sovereignty, every official action taken by that regime is illegal and void except for its registration of births, marriages and deaths. This is called the “Namibia exception,” which is a decision by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in 1971 called the Legal Consequences for States of the Continued Presence of South Africa in Namibia (South West Africa) notwithstanding Security Council Resolution 276 (1970).

In 1966, the United Nations General Assembly passed resolution 2145 (XXI) that terminated South Africa’s administration of Namibia, formerly known as South West Africa, a former German colony. This resulted in Namibia coming under the administration of the United Nations, but South Africa refused to withdraw from Namibian territory and consequently the situation transformed into an illegal occupation. As a former German colony, Namibia became a mandate territory under the administration of South Africa after the close of the First World War.

Addressing the legal consequences arising for South Africa’s refusal to leave Namibia, the ICJ stated that by “occupying the Territory without title, South Africa incurs international responsibilities arising from a continuing violation of an international obligation,” and that all countries, whether a member of the United Nations or not were “under an obligation to recognize the illegality and invalidity of South Africa’s continued presence in Namibia and to refrain from lending any support or any form of assistance to South Africa with reference to its occupation of Namibia.” The ICJ, however, clarified that “non-recognition should not result in depriving the people of Namibia of any advantages derived from international cooperation.

The conduct of an illegal regime during occupation is limited and confined to the international laws of occupation and to the principle of ex injuria ius non oritur—where unlawful acts cannot be the source of lawful rights. According to Ronen, p. 39, “Opposite the principle of ex injuria jus non oritur operates the principle ex factis ius oritur. It mandates that acts of the illegal regime may have legal consequences despite the illegality and status of the regime that performed them.” Ronen explains, “In other words, the general invalidity of domestic acts carried out under an illegal regime is qualified where such invalidity would act to the detriment of the inhabitants of the territory. This is the Namibia exception.” The ICJ in the Namibia case explained, “the principle ex injuria jus non oritur dictates that acts which are contrary to international law cannot become a source of legal acts for the wrongdoer… To grant recognition to illegal acts or situation will tend to perpetuate it and be benefitial to the state which has acted illegally.”

The focus of the Namibia exception is to protect the interests of the nationals of the occupied State and not to entrench the authority of an illegal regime. The validity of any other official acts of an illegal regime other than the registration of births, marriages and deaths must not serve “to the detriment of the inhabitants of the territory” being occupied and must not be seen to further “entrench the authority of an illegal regime.”

The Hawaiian Kingdom at the Permanent Court of Arbitration (1999-2001)

https://vimeo.com/17007826

On November 8, 1999, international arbitration proceedings were initiated at the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA), The Hague, Netherlands, between Lance Paul Larsen and the acting Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom (Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom). The arbitration agreement provided, “The Arbitral Tribunal is asked to determine, on the basis of the Hague Conventions IV and V of 18 October 1907, and the rules and principles of international law, whether the rights of the Claimant under international law as a Hawaiian subject are being violated, and if so, does he have any redress against the Respondent Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom?”

Larsen was arrested on October 4, 1999, in Hilo, Hawai‘i, and imprisoned for 30 days, seven of which were in solitary confinement, for following Hawaiian Kingdom law. Larsen, as the Claimant, alleged that the acting government, the Respondent, was  legally liable to him for allowing the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws over him within the territorial jurisdiction of the Hawaiian Kingdom. In the pleading, Larsen’s attorney, Ms. Ninia Parks, esq., based her case on the following grounds:

legally liable to him for allowing the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws over him within the territorial jurisdiction of the Hawaiian Kingdom. In the pleading, Larsen’s attorney, Ms. Ninia Parks, esq., based her case on the following grounds:

- Mr. Larsen is a Hawaiian subject, with a Hawaiian nationality.

- As a Hawaiian subject, Mr. Larsen is bound by Hawaiian Kingdom law. He is not bound by the laws of the State of Hawaii nor by the laws of the United States of America.

- Mr. Larsen’s rights as a Hawaiian subject have been systematically and continuously denied by the United States of America, the occupying force in the prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian islands by the United States of America. At a minimum, the United States of America has continually denied Mr. Larsen’s nationality as a Hawaiian subject, has illegally imposed American laws over his person, has extorted monetary fines from Mr. Larsen under threat of imprisonment, and has imprisoned Mr. Larsen for asserting his lawful rights as a Hawaiian national.

- The government of the Hawaiian Kingdom has a duty to protect the rights of Mr. Larsen, a Hawaiian subject, despite the continued occupation of the Hawaiian Islands by the United States of America.

- The government of the Hawaiian Kingdom, through its acting Regency, has not fulfilled this duty.

In its pleading, the acting Government, represented by Dr. Keanu Sai as lead agent, denied the allegations and submitted “that the Claimant’s rights under international law are being violated, but to what extent, is left to the Arbitral Tribunal to decide. That this decision must be made within fixed and established principles and laws pertaining to the matter, and that the Hawaiian Kingdom Government is not liable for redress of these violations under its present conditions as an occupied State.”

In its pleading, the acting Government, represented by Dr. Keanu Sai as lead agent, denied the allegations and submitted “that the Claimant’s rights under international law are being violated, but to what extent, is left to the Arbitral Tribunal to decide. That this decision must be made within fixed and established principles and laws pertaining to the matter, and that the Hawaiian Kingdom Government is not liable for redress of these violations under its present conditions as an occupied State.”

In the American Journal of International Law, vol. 95, p. 928 (2001), and reprinted in the Hawaiian Journal of Law and Politics, vol. 1, p. 83 (2004), Bederman and Hilbert, state that at “the center of the PCA proceeding was…that the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist and that the Hawaiian Council of Regency (representing the Hawaiian Kingdom) is legally responsible under international law for the protection of Hawaiian subjects, including the claimant. In other words, the Hawaiian Kingdom was legally obligated to protect Larsen from the United States’ ‘unlawful imposition [over him] of [its] municipal laws’ through its political subdivision, the State of Hawai‘i. As a result of this responsibility, Larsen submitted, the Hawaiian Council of Regency should be liable for any international law violations that the United States committed against him.”

In February 2000, the PCA’s Secretary General Tjaco T. van den Hout recommended that the acting Government provide a formal invitation to the United States to join in the arbitration. In order to carry out this request by the Secretary General, Dr. Sai was sent to Washington, D.C. Ms. Ninia Parks, attorney for the Claimant Lance Larsen, accompanied Dr. Sai.

In February 2000, the PCA’s Secretary General Tjaco T. van den Hout recommended that the acting Government provide a formal invitation to the United States to join in the arbitration. In order to carry out this request by the Secretary General, Dr. Sai was sent to Washington, D.C. Ms. Ninia Parks, attorney for the Claimant Lance Larsen, accompanied Dr. Sai.

On March 3, 2000, a telephone meeting with John R. Crook, Assistant Legal Adviser for United Nations Affairs section of the US Department of State, was held. It was stated to Mr. Crook that the “visit was to provide these documents to the Legal Department of the U.S. Department of State in order for the U.S. Government to be apprised of the arbitral proceedings already in train and that the Hawaiian Kingdom, by consent of the Claimant, extends an opportunity for the United States to join in the arbitration as a party.”

On March 3, 2000, a telephone meeting with John R. Crook, Assistant Legal Adviser for United Nations Affairs section of the US Department of State, was held. It was stated to Mr. Crook that the “visit was to provide these documents to the Legal Department of the U.S. Department of State in order for the U.S. Government to be apprised of the arbitral proceedings already in train and that the Hawaiian Kingdom, by consent of the Claimant, extends an opportunity for the United States to join in the arbitration as a party.”

Mr. Crook was made fully aware of the United States occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the establishment of the acting Government. This direct challenge to US sovereignty over the Hawaiian Islands should have prompted the United States to protest the action taken by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in accepting the Hawaiian arbitration case and call upon the Secretary General to cease and desist because this action constitutes a violation of US sovereignty. The United States did  neither. Instead, Deputy Secretary General Phyllis Hamilton notified the acting Government that the United States notified the Court that it will not join in the arbitration, but did request from the acting government permission to access all pleadings and transcripts of the case. Both the acting government and Larsen’s attorney consented. By this action, the United States directly acknowledged the circumstances of the proceedings and the acting government’s representation of the Hawaiian Kingdom before an international tribunal.

neither. Instead, Deputy Secretary General Phyllis Hamilton notified the acting Government that the United States notified the Court that it will not join in the arbitration, but did request from the acting government permission to access all pleadings and transcripts of the case. Both the acting government and Larsen’s attorney consented. By this action, the United States directly acknowledged the circumstances of the proceedings and the acting government’s representation of the Hawaiian Kingdom before an international tribunal.

Three distinguished jurists presided on the Arbitration Tribunal. Professor James Crawford, SC, served as Presiding arbitrator. Professor Crawford is a professor of international law at the University of Cambridge. At the time of the arbitration, Crawford was also a member of the United Nations International Law Commission (ILC) and was responsible for the ILC’s work on the International Criminal Court (1994) and the Articles on State Responsibility (2001).

Three distinguished jurists presided on the Arbitration Tribunal. Professor James Crawford, SC, served as Presiding arbitrator. Professor Crawford is a professor of international law at the University of Cambridge. At the time of the arbitration, Crawford was also a member of the United Nations International Law Commission (ILC) and was responsible for the ILC’s work on the International Criminal Court (1994) and the Articles on State Responsibility (2001).

Judge Sir Christopher Greenwood, QC, served as Associate arbitrator. Greenwood was at the time professor of international law at the London School of Economics and Political Science and legal counsel to the United Nations on the Laws of War and Occupation. In 2008, the United Nations elected Greenwood to be judge on the International Court of Justice.

Judge Sir Christopher Greenwood, QC, served as Associate arbitrator. Greenwood was at the time professor of international law at the London School of Economics and Political Science and legal counsel to the United Nations on the Laws of War and Occupation. In 2008, the United Nations elected Greenwood to be judge on the International Court of Justice.

Dr. Gavan Griffith, QC, served as Associate Arbitrator. Griffith was former Solicitor General for Australia and also served as counsel and agent for Australia in Nauru v. Australia before the International Court of Justice.

Dr. Gavan Griffith, QC, served as Associate Arbitrator. Griffith was former Solicitor General for Australia and also served as counsel and agent for Australia in Nauru v. Australia before the International Court of Justice.

Three days of oral hearings were set for December 7, 8 and 11, 2000 at the PCA. At the center of these proceedings was whether or not Larsen was able to maintain his suit against the acting Government for not protecting him without the participation of the United States who would need to answer to the alleged violations committed by them against Larsen. Larsen was attempting to hold the acting Government responsible for his injuries committed by the United States. In international law, this is a situation called the “necessary and indispensable party” rule and it was the basis of decisions made by the International Court of Justice in Monetary Gold case (Italy v. France, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and United States of America), the Nauru case (Nauru v. Australia), and the East Timor case (Portugal v. Australia).

In the 2001 Arbitral Award, the Tribunal explained, that it “cannot determine whether the Respondent [the acting government] has failed to discharge its obligations towards the Claimant [Larsen] without ruling on the legality of the acts of the United States of America. Yet that is precisely what the Monetary Gold principle precludes the Tribunal from doing. As the International Court explained in the East Timor case, ‘the Court could not rule on the lawfulness of the conduct of a State when its judgment would imply an evaluation of the lawfulness of the conduct of another State which is not a party to the case.’”

The Tribunal, however, did acknowledge the Hawaiian Kingdom to be an independent State. In its decision, the Tribunal concluded in the Award, “that in the nineteenth century the Hawaiian Kingdom existed as an independent State recognized as such by the United States of America, the United Kingdom and various other States, including by exchanges of diplomatic or consular representatives and the conclusion of treaties.” International law provides for the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom since the nineteenth century to the present, which was the basis for the arbitration case in the first place.

‘Iolani School Students Reenact Historical Trial at ‘Iolani Palace

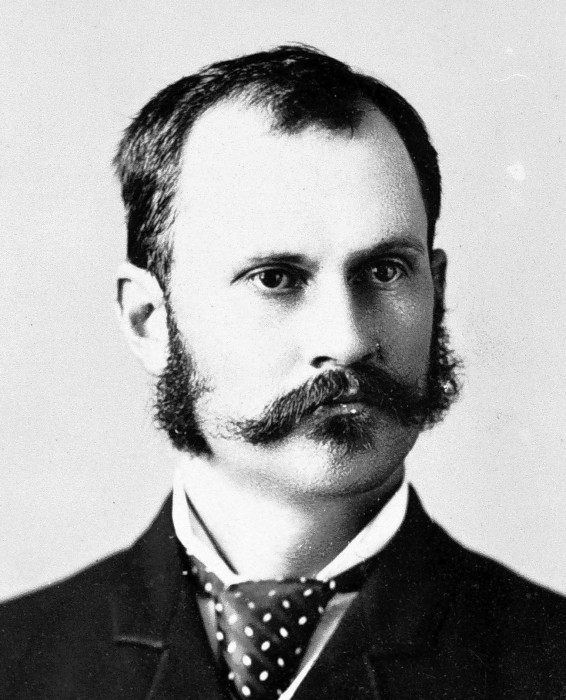

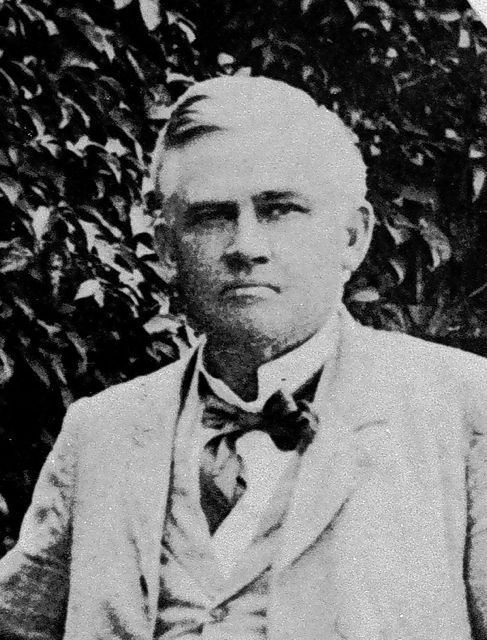

On March 6, 2014, KITV News aired a story where ‘Iolani School students reenacted a historical trial of Lorrin Thurston, who was the lead insurgent when the United States illegally overthrew the Hawaiian Kingdom government in 1893, was put on trial for treason. Thurston was a Hawaiian subject and an attorney in the Hawaiian Kingdom. He was the leader of the insurgency that got the U.S. Ambassador John Stevens to land U.S. troops to protect them from arrest by the Hawaiian authorities in order to declare themselves and new government. U.S. Special Commissioner James Blount who was appointed by President Grover Cleveland to investigate whether or not U.S. troops were involved, concluded, “in pursuance of a prearranged plan, the Government thus established hastened off commissioners to Washington to make a treaty for the purpose of annexing the Hawaiian Islands to the United States.”

On March 6, 2014, KITV News aired a story where ‘Iolani School students reenacted a historical trial of Lorrin Thurston, who was the lead insurgent when the United States illegally overthrew the Hawaiian Kingdom government in 1893, was put on trial for treason. Thurston was a Hawaiian subject and an attorney in the Hawaiian Kingdom. He was the leader of the insurgency that got the U.S. Ambassador John Stevens to land U.S. troops to protect them from arrest by the Hawaiian authorities in order to declare themselves and new government. U.S. Special Commissioner James Blount who was appointed by President Grover Cleveland to investigate whether or not U.S. troops were involved, concluded, “in pursuance of a prearranged plan, the Government thus established hastened off commissioners to Washington to make a treaty for the purpose of annexing the Hawaiian Islands to the United States.”

To view the KITV news coverage of the historical trial go to this link.

‘Iolani School is a private school that was established in 1863 by Father William R. Scott of the Anglican faith. The former name of the school was Lua‘ehu, but it was renamed ‘Iolani in 1870 by the former Queen Emma when it moved from the city of Lahaina to Honolulu. The school’s patron saints are King Kamehameha IV and Queen Emma.

Here is the transcript of KITV’s coverage.

HONOLULU —The ‘Iolani palace throne room, the very room where former Queen Lili’uokalani was put on trial for treason, was turned into a court room Thursday.

At first glance you feel like you have been transported back in time to the trial of Lili’uokalani. The palace throne room was set up for the case, but well over a century later comes a twist; Iolani School history students are putting Lorrin Thurston on trial.

Thurston played a prominent role in the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarch; the witnesses historical figures of that time.

“How do you feel about Lorrin Thurston and his overthrow of Hawaii? I believe he’s guilty. He led the overthrow. He acted on his own accord. He started the Committee of Safety and he also wrongfully used the U.S. Navy as intimidation during the coup,” said Senator James Blount, author of the Blount Report. “You did not take the opinion of the coup? I didn’t have them for my report. I envied the local population. Why? Cause they would have been biased.”

Taking their assignment seriously most dressed the part and sounded the part too.

“The Angle Franco Treaty…I agreed to recognize the Hawaiian Kingdom as a sovereign,” said Queen Victoria, a friend of Queen Lili’uokalani.

“I didn’t betray her. I did what I thought would be best for the people,” said Sanford Dole, President of the Republic of Hawaii.

“Did the annexation of Hawaii benefit the landowner more or was it made for the people — the Native Hawaiians? It was for everyone living in Hawaii,” said Max Webber, an Iolani School 12th grader playing Thurston.

After a brief deliberation, the jury decides.

“Your honor, we the jury find Lorrin Thurston guilty of the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom,” said a student cast in the jury.

A sigh came from Weber, who played Thurston and dove right into the project.

“I read there all these books about him and he had a book he wrote about himself. So, I went through and read a lot of that and I also ideas of what he was thinking during that time,” said Weber.

“‘Iolani Palace is taking a new initiative to focus more on education and going outside of the four walls of the classrooms is so much more effective,” said ‘Iolani Palace Executive Director Kippen de alba Chu

Iolani School history teacher Melanie Pfingstem, who played the judge, agrees.

“Well I just think that simulations are really a great way for kids to internalize history,” said Pfingstem.

“This whole experience has really given us the details and the exact circumstances around the overthrow and the part each player played. That was really eye opening to how Hawaii became what it is today,” Michelle Kimura, an Iolani School 10th grader who portrayed Lili’uokalani.

Hawai‘i and the Crimean Crisis – Obama is not a Legitimate President

Putting aside the violence that has caused injuries and death in Ukraine on both the government and protesters side, what does the law say regarding the removal of Ukraine’s President Victor Yanukovych by vote of the Ukrainian Parliament (Rada). In The Daily Beast article “How Ukraine’s Parliament Brought Down Yanukovych,” there was no mention of Ukrainian law, except for legislation passed by the Rada. The Daily Beast reported, “after Yanukovych refused to leave office, the Ukrainian parliament by an overwhelming majority voted to remove him from the post as the one who ‘has dissociated himself’ by fleeing the capital. The ballot was passed with a constitutional majority and entered into force immediately.”

Putting aside the violence that has caused injuries and death in Ukraine on both the government and protesters side, what does the law say regarding the removal of Ukraine’s President Victor Yanukovych by vote of the Ukrainian Parliament (Rada). In The Daily Beast article “How Ukraine’s Parliament Brought Down Yanukovych,” there was no mention of Ukrainian law, except for legislation passed by the Rada. The Daily Beast reported, “after Yanukovych refused to leave office, the Ukrainian parliament by an overwhelming majority voted to remove him from the post as the one who ‘has dissociated himself’ by fleeing the capital. The ballot was passed with a constitutional majority and entered into force immediately.”

President Obama calls the new government legitimate, but President Putin calls it illegitimate. According to Article 108 of the Ukrainian Constitution, “The authority of the President of Ukraine shall be subject to an early termination in cases of: (1) resignation; (2) inability to exercise presidential authority for health reasons; (3) removal from office by the procedure of impeachment; (4) his/her death.” Since Yanukovych didn’t resign and he had no health issues, the only way to remove him would be “by the procedure of impeachment.” The quintessential question is whether a vote of removal by the Rada constituted impeachment. If it was then Yanukovych is no longer President, but if not then the Rada vote was unconstitutional and Yanukovych is still President even while he is in Russia.

President Obama calls the new government legitimate, but President Putin calls it illegitimate. According to Article 108 of the Ukrainian Constitution, “The authority of the President of Ukraine shall be subject to an early termination in cases of: (1) resignation; (2) inability to exercise presidential authority for health reasons; (3) removal from office by the procedure of impeachment; (4) his/her death.” Since Yanukovych didn’t resign and he had no health issues, the only way to remove him would be “by the procedure of impeachment.” The quintessential question is whether a vote of removal by the Rada constituted impeachment. If it was then Yanukovych is no longer President, but if not then the Rada vote was unconstitutional and Yanukovych is still President even while he is in Russia.

By definition, impeachment is not removal, but rather a process initiated by a legislative body in order to remove a President. Impeachment is similar to an indictment, which precedes a trial. Under the United States Constitution this two-step process begins when the House of Representatives votes for articles of impeachment by a majority of  those Representatives present, which provides the allegations of “treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.” If the articles of impeachment pass, the President is considered impeached. What follows is for the Senate to hold a trial, which is presided over by the Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1999, President Bill Clinton was impeached, but was found not guilty in the Senate trial.

those Representatives present, which provides the allegations of “treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.” If the articles of impeachment pass, the President is considered impeached. What follows is for the Senate to hold a trial, which is presided over by the Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1999, President Bill Clinton was impeached, but was found not guilty in the Senate trial.

The Ukrainian Constitution provides for the process of impeaching its President.

“Article 111. The President of Ukraine may be removed from the office by the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine in compliance with a procedure of impeachment if he commits treason or other crime.

The issue of the removal of the President of Ukraine from the office in compliance with a procedure of impeachment shall be initiated by the majority of the constitutional membership of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine.

The Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine shall establish a special ad hoc investigating commission, composed of special prosecutor and special investigators to conduct an investigation.

The conclusions and proposals of the ad hoc investigating commission shall be considered at the meeting of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine.

On the ground of evidence, the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine shall, by at least two-thirds of its constitutional membership, adopt a decision to bring charges against the President of Ukraine.

The decision on the removal of the President of Ukraine from the office in compliance with the procedure of impeachment shall be adopted by the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine by at least three-quarters of its constitutional membership upon a review of the case by the Constitutional Court of Ukraine, and receipt of its opinion on the observance of the constitutional procedure of investigation and consideration of the case of impeachment, and upon a receipt of the opinion of the Supreme Court of Ukraine to the effect that the acts, of which the President of Ukraine is accused, contain elements of treason or other crime.”

The Rada’s vote to remove President Yanukovych does not appear to be following this constitutional process and it can be argued that Yanukovych’s removal was  unconstitutional, which is what Russia has been stating. Russia

unconstitutional, which is what Russia has been stating. Russia also has stated that Yanukovych’s removal was supported by the United States, especially after a phone conversation between assistant U.S. Secretary of State Victoria Nuland and U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine, Geoffrey Pyatt, was leaked to the media. On February 7, 2014, The Guardian reported on the phone conversation and played the audio.

also has stated that Yanukovych’s removal was supported by the United States, especially after a phone conversation between assistant U.S. Secretary of State Victoria Nuland and U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine, Geoffrey Pyatt, was leaked to the media. On February 7, 2014, The Guardian reported on the phone conversation and played the audio.

With the world’s focus on whether Yanukovych is still President according to Ukrainian law and not international law, there is a question of Presidential legitimacy the world may not know, which is the legitimacy of United States President Barrack Obama under United States law. Article II of the United States Constitution provides, “No Person except a natural born Citizen, or a Citizen of the United States, at the time of the Adoption of this Constitution, shall be eligible to the Office of President.” The term natural born (jus soli) is a person who acquires United States citizenship through birth on United States territory. This is different from U.S. citizenship acquired through naturalization, which has a residency requirement, and U.S. citizenship acquired through parentage (jus sanguinis) when born outside of the United States.

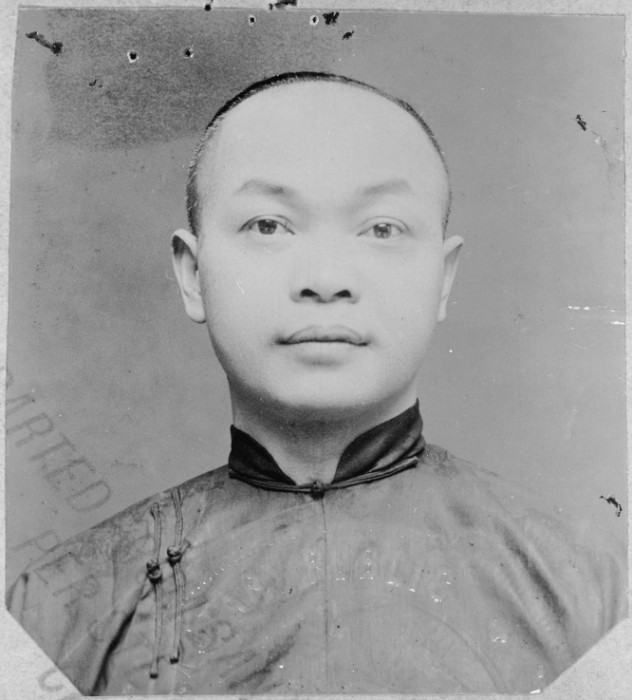

The leading case in the United States on the definition of “natural-born” is the 1898 U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in U.S. v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649. In that case, the Court confirmed that Wong Kim Ark, a child of Chinese nationals born in the city of San Francisco, was a natural-born United States citizen. The Court’s reasoning was that since the term “natural-born” was specifically used in the United States Constitution, which was written in 1787, English common law was to be used in its interpretation of natural-born. The Court explained, “The interpretation of the Constitution of the United States is necessarily influenced by the fact that its provisions are framed in the language of the English common law, and are to be read in the light of its history.”

The leading case in the United States on the definition of “natural-born” is the 1898 U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in U.S. v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649. In that case, the Court confirmed that Wong Kim Ark, a child of Chinese nationals born in the city of San Francisco, was a natural-born United States citizen. The Court’s reasoning was that since the term “natural-born” was specifically used in the United States Constitution, which was written in 1787, English common law was to be used in its interpretation of natural-born. The Court explained, “The interpretation of the Constitution of the United States is necessarily influenced by the fact that its provisions are framed in the language of the English common law, and are to be read in the light of its history.”

The Court further explained, “The fundamental principle of the common law with regard to English nationality was birth within the allegiance, also called ‘ligealty,’ ‘obedience,’ ‘faith,’ or ‘power’ of the King. The principle embraced all persons born within the King’s allegiance and subject to his protection. Such allegiance and protection were mutual — as expressed in the maxim protectio trahit subjectionem, et subjectio protectionem — and were not restricted to natural-born subjects and naturalized subjects, or to those who had taken an oath of allegiance, but were predicable of aliens in amity so long as they were within the kingdom. Children, born in England, of such aliens were therefore natural-born subjects. But the children, born within the realm, of foreign ambassadors, or the children of alien enemies, born during and within their hostile occupation of part of the King’s dominions, were not natural-born subjects because not born within the allegiance, the obedience, or the power, or, as would be said at this day, within the jurisdiction, of the King.”

Two of the Judges, however, dissented with the judgment on racial grounds, but they also allude to what it meant to children born abroad of U.S. parents. Both judges stated, “Considering the circumstances surrounding the framing of the Constitution, I submit that it is unreasonable to conclude that ‘natural-born citizen’ applied to everybody born within the geographical tract known as the United States, …while children of our citizens, born abroad, were not.”

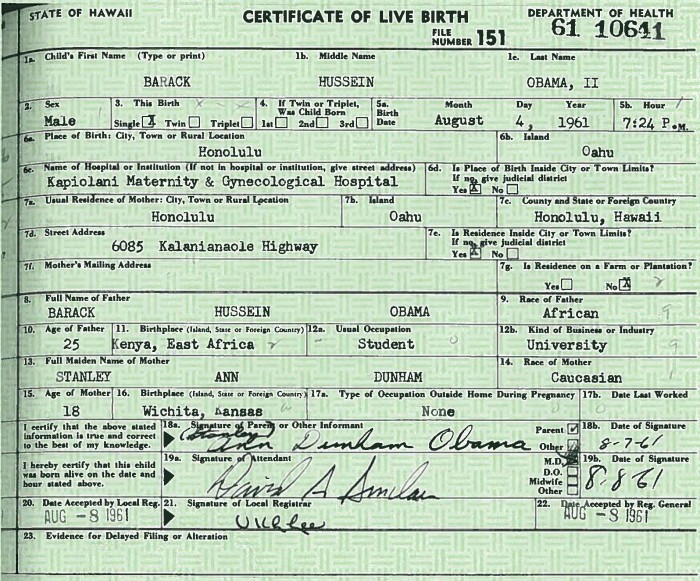

Obama was born in the Hawaiian Kingdom and not the United States. He was born in the city of Honolulu on August 4, 1961 at Kapi‘olani Hospital, which was established in 1890 by the Hawaiian Kingdom’s Queen Kapi‘olani.

Since the Hawaiian Kingdom has been under an illegal and prolonged occupation by the United States and its continuity is protected under international law, Obama cannot claim to be a natural-born citizen of the United States and, therefore, cannot meet the constitutional requirement to be a President of the United States. But he is a U.S. citizen through parentage (jus sanguinis) because his mother was a U.S. citizen when she gave birth to Obama in the Hawaiian Kingdom. He cannot, however, claim Hawaiian citizenship by birth because the international law of occupation, which protects and maintains the status quo of the occupied State, only allows Hawaiian citizenship through parentage and not natural-born even though it is a recognized mode of acquiring citizenship under Hawaiian Kingdom law.

State Attributes of the Hawaiian Kingdom

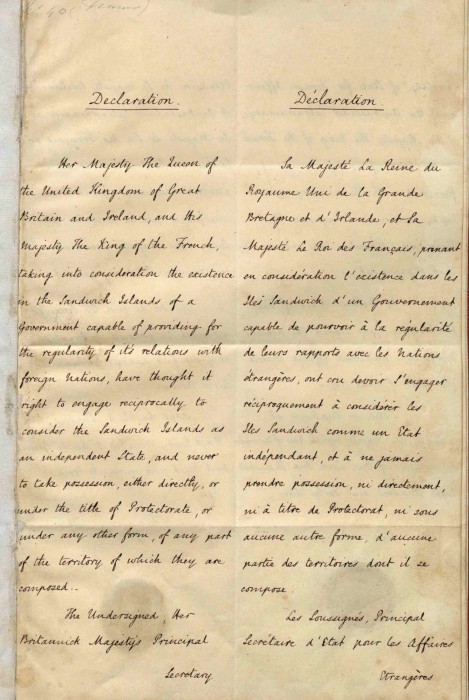

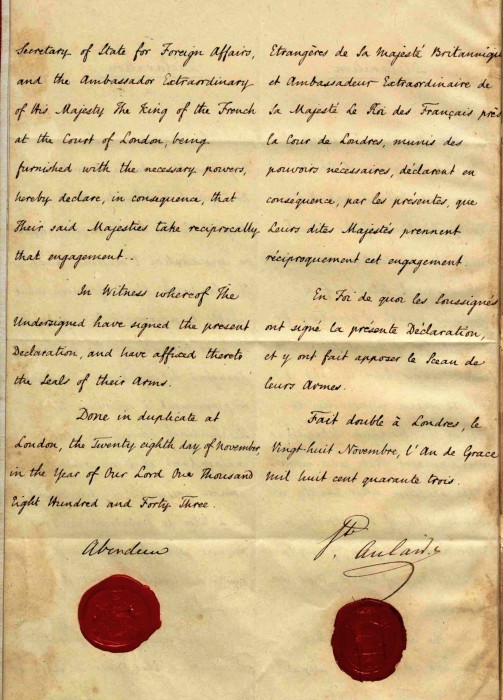

The Hawaiian Kingdom received the recognition of its independence and sovereignty by joint proclamation from the United Kingdom and France on November 28, 1843, and by the United States of America on July 6, 1844.

At the time of the recognition of Hawaiian independence, the Hawaiian Kingdom’s government was a constitutional monarchy that developed a complete system of laws, both civil and criminal, and have treaty relations of a most favored nation status with the major powers of the world, including the United States of America.

At the time of the recognition of Hawaiian independence, the Hawaiian Kingdom’s government was a constitutional monarchy that developed a complete system of laws, both civil and criminal, and have treaty relations of a most favored nation status with the major powers of the world, including the United States of America.

A. Permanent Population

According to Professor Crawford, The Creation of States in International Law, 2nd ed. (2006), p. 52, “If States are territorial entities, they are also aggregates of individuals. A permanent population is thus necessary for statehood, though, as in the case of territory, no minimum limit is apparently prescribed.” Professor Giorgetti, A Principled Approach to State Failure (2010), p. 55, explains “Once recognized, States continue to exist and be part of the international community even if their population changes. As such, changes in one of the fundamental requirements of statehood do not alter the identity of the State once recognized.”

In his report to U.S. Secretary of State Walter Gresham, Special Commissioner James Blount reported on June 1, 1893, “The population of the Hawaiian Islands can but be studied by one unfamiliar with the native tongue from its several census reports. A census is taken every six years. The last report is for the year 1890. From this it appears that the whole population numbers 89,990. This number includes natives, or, to use another designation, Kanakas, half-castes (persons containing an admixture of other than native blood in any proportion with it), Hawaiian-born foreigners of all races or nationalities other than natives, Americans, British, Germans, French, Portuguese, Norwegians, Chinese, Polynesians, and other nationalities. Americans numbered 1,928; natives and half-castes, 40,612; Chinese, 15,301; Japanese, 12,360; Portuguese, 8,602; British, 1,344; Germans, 1,034; French, 70; Norwegians, 227; Polynesians, 588; and other foreigners 419. It is well at this point to say that of the 7,495 Hawaiian-born foreigners 4,117 are Portuguese, 1,701 Chinese and Japanese, 1,617 other white foreigners, and 60 of other nationalities.”

In his report to U.S. Secretary of State Walter Gresham, Special Commissioner James Blount reported on June 1, 1893, “The population of the Hawaiian Islands can but be studied by one unfamiliar with the native tongue from its several census reports. A census is taken every six years. The last report is for the year 1890. From this it appears that the whole population numbers 89,990. This number includes natives, or, to use another designation, Kanakas, half-castes (persons containing an admixture of other than native blood in any proportion with it), Hawaiian-born foreigners of all races or nationalities other than natives, Americans, British, Germans, French, Portuguese, Norwegians, Chinese, Polynesians, and other nationalities. Americans numbered 1,928; natives and half-castes, 40,612; Chinese, 15,301; Japanese, 12,360; Portuguese, 8,602; British, 1,344; Germans, 1,034; French, 70; Norwegians, 227; Polynesians, 588; and other foreigners 419. It is well at this point to say that of the 7,495 Hawaiian-born foreigners 4,117 are Portuguese, 1,701 Chinese and Japanese, 1,617 other white foreigners, and 60 of other nationalities.”

The permanent population has exceedingly increased since the 1890 census and according to the last census in 2011 by the United States that number was at 1,374,810. International law, however, protects the status quo of the national population of an occupied State during occupation. According to Professor von Glahn, The Occupation of Enemy Territory: A Commentary on the Law and Practice of Belligerent Occupation (1957), p. 60, “the nationality of the inhabitants of occupied areas does not ordinarily change through the mere fact that temporary rule of a foreign government has been instituted, inasmuch as military occupation does not confer de jure sovereignty upon an occupant. Thus under the laws of most countries, children born in territory under enemy occupation possess the nationality of their parents, that is, that of the legitimate sovereign of the occupied area.” Any individual today who is a direct descendent of a person who lawfully acquired Hawaiian citizenship prior to the U.S. occupation that began at noon on August 12, 1898, is a Hawaiian subject. Hawaiian law recognizes all others who possess the nationality of their parents as part of the alien population.

B. Defined Territory

According to Judge Huber, in the Island of Palmas arbitration case, “Territorial sovereignty…involves the exclusive right to display the activities of a State.” Crawford, p. 56, also states, “Territorial sovereignty is not ownership of but governing power with respect to territory.”

§6 of the Compiled Laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom states, “The laws are obligatory upon all persons, whether subjects of this kingdom, or citizens or subjects of any foreign State, while within the limits of this kingdom, except so far as exception is made by the laws of nations in respect to Ambassadors or others. The property of all such persons, while such property is within the territorial jurisdiction of this kingdom, is also subject to the laws.”

The Islands constituting the defined territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom on January 17, 1893, together with its territorial seas whereby the channels between adjacent Islands are contiguous, its exclusive economic zone of two hundred miles, and its air space, include:

Island: Location: Square Miles/Acreage:

Hawai‘i 19º 30′ N 155º 30′ W 4,028.2 / 2,578,048

Maui 20º 45′ N 156º 20′ W 727.3 / 465,472

O‘ahu 21º 30′ N 158º 00′ W 597.1 / 382,144

Kaua‘i 22º 03′ N 159º 30′ W 552.3 / 353,472

Molokai 21º 08′ N 157º 00′ W 260.0 / 166,400

Lana‘i 20º 50′ N 156º 55′ W 140.6 / 89,984

Ni‘ihau 21º 55′ N 160º 10′ W 69.5 / 44,480

Kaho‘olawe 20º 33′ N 156º 35′ W 44.6 / 28,544

Nihoa 23º 06′ N 161º 58′ W 0.3 / 192

Molokini 20º 38′ N 156º 30′ W 0.04 / 25.6

Lehua 22º 01′ N 160º 06′ W 0.4 / 256

Ka‘ula 21º 40′ N 160º 32′ W 0.2 / 128

Laysan 25º 50′ N 171º 50′ W 1.6 / 1,024

Lisiansky 26º 02′ N 174º 00′ W 0.6 / 384

Palmyra 05º 52′ N 162º 05′ W 4.6 / 2,944

Ocean 28º 25′ N 178º 25′ W 0.4 / 256

TOTAL: 6,427.74 (square miles) / 4,113,753.6 (acres)

C. Government

According to Crawford, p. 56, “Governmental authority is the basis for normal inter-State relations; what is an act of a State is defined primarily by reference to its organs of government, legislative, executive or judicial.” Since 1864, the Hawaiian Kingdom fully adopted the separation of powers doctrine in its constitution, being the cornerstone of constitutional governance.

Article 20, Hawaiian Constitution. The Supreme Power of the Kingdom in its exercise, is divided into the Executive, Legislative, and Judicial; these shall always be preserved distinct, and no Judge of a Court of Record shall ever be a member of the Legislative Assembly.

Article 31, Hawaiian Constitution. To the King belongs the executive power.

Article 45, Hawaiian Constitution. The Legislative power of the Three Estates of this Kingdom is vested in the King, and the Legislative Assembly; which Assembly shall consist of the Nobles appointed by the King, and of the Representatives of the People, sitting together.

Article 66, Hawaiian Constitution. The Judicial Power shall be divided among the Supreme Court and the several Inferior Courts of the Kingdom, in such manner as the Legislature may, from time to time, prescribe, and the tenure of office in the Inferior Courts of the Kingdom shall be such as may be defined by the law creating them.

1. Power to Declare and Wage War & to Conclude Peace

The power to declare war and to conclude peace is constitutionally vested in the office of the Monarch pursuant to Article 26, Hawaiian Constitution, “The King is the Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy, and for all other Military Forces of the Kingdom, by sea and land; and has full power by himself, or by any officer or officers he may judge best for the defense and safety of the Kingdom. But he shall never proclaim war without the consent of the Legislative Assembly.”

2. To Maintain Diplomatic Ties with Other Sovereigns

Maintaining diplomatic ties with other States is vested in the office of the Monarch pursuant to Article 30, Hawaiian Constitution, “It is the King’s Prerogative to receive and acknowledge Public Ministers…” The officer responsible for maintaining diplomatic ties with other States is the Minister of Foreign Affairs whose duty is “to conduct the correspondence of [the Hawaiian] Government, with the diplomatic and consular agents of all foreign nations, accredited to this Government, and with the public ministers, consuls, and other agents of the Hawaiian Islands, in foreign countries, in conformity with the law of nations, and as the King shall from time to time, order and instruct.” §437, Compiled Laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom. The Minister of Foreign Affairs shall also “have the custody of all public treaties concluded and ratified by the Government; and it shall be his duty to promulgate the same by publication in the government newspaper. When so promulgated, all officers of this government shall be presumed to have knowledge of the same.” §441, Compiled Laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

3. To Acquire Territory by Discovery or Occupation

Between 1822 and 1886, the Hawaiian Kingdom exercised the power of discovery and occupation that added five additional islands to the Hawaiian Domain. By direction of Ka‘ahumanu in 1822, Captain William Sumner took possession of the Island of Nihoa. On May 1, 1857; Laysan Island was taken possession by Captain John Paty for the Hawaiian Kingdom; on May 10, 1857 Captain Paty also took possession of Lysiansky Island; Palmyra Island was taken possession of by Captain Zenas Bent on April 15, 1862; and Ocean Island was acquired September 20, 1886, by proclamation of Colonel J.H. Boyd.

4. To Make International Agreements and Treaties and Maintain Diplomatic Relations with other States

Article 29, Hawaiian Constitution, provides, “The King has the power to make Treaties. Treaties involving changes in the Tariff or in any law of the Kingdom shall be referred for approval to the Legislative Assembly.” As a result of the United States of America’s recognition of Hawaiian independence, the Hawaiian Kingdom entered into a Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation, Dec. 20, 1849; Treaty of Commercial Reciprocity, Jan. 13, 1875; Postal Convention Concerning Money Orders, Sep. 11, 1883; and a Supplementary Convention to the 1875 Treaty of Commercial Reciprocity, Dec. 6, 1884.

The Hawaiian Kingdom also entered into treaties with Austria-Hungary (now separate States), June 18, 1875; Belgium, October 4, 1862; Denmark, October 19, 1846; France, September 8, 1858; Germany, March 25, 1879; the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, March 26, 1846; Italy, July 22, 1863; Japan, August 19, 1871, January 28, 1886; Netherlands, October 16, 1862; Portugal, May 5, 1882; Russia, June 19, 1869; Spain, October 9, 1863; Sweden-Norway (now separate States), April 5, 1855; and Switzerland, July 20, 1864.

Foreign Legations accredited to the Court of the Hawaiian Kingdom in the city of Honolulu included the United States of America, Portugal, Great Britain, France and Japan.

Foreign Consulates in the Hawaiian Kingdom included the United States of America, Italy, Chile, Germany, Sweden-Norway, Denmark, Peru, Belgium, Netherlands, Spain, Austria-Hungary, Russia, Great Britain, Mexico and China.

Hawaiian Legations accredited to foreign States included the United States of America in the city of Washington, D.C.; Great Britain in the city of London; France in the city of Paris, Russia in the city of Saint Petersburg; Peru in the city of Lima; and Chile in the city of Valparaiso.

Hawaiian Consulates in foreign States included the United States of America in the cities of New York, San Francisco, Philadelphia, San Diego, Boston, Portland, Port Townsend and Seattle; Mexico in Mexico city and the city of Manzanillo; Guatemala; Peru in the city of Callao; Chile in the city of Valparaiso; Uruguay in the city of Monte Video; Philippines (former Spanish territory) in the city of Iloilo and Manila; Great Britain in the cities of London, Bristol, Hull, Newcastle on Tyne, Falmouth, Dover, Cardiff and Swansea, Edinburgh and Leith, Glasgow, Dundee, Queenstown, and Belfast; Ireland, in the cities of Liverpool, and Dublin; Canada (former British territory) in the cities of Toronto, Montreal, Bellville, Kingston Rimouski, St. John’s, Varmouth, Victoria, and Vancouver; Australia in the cities of Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Hobart, and Launceston; New Zealand (former British territory) in the cities of Auckland and Dunedin; China in the cities of Hong Kong and Shanghai; France in the cities of Paris, Marseilles, Bordeaux, Dijon, Libourne and Papeete; Germany in the cities of Bremen, Hamburg, Frankfort, Dresden and Karlsruhe; Austria in the city of Vienna; Spain in the cities of Barcelona, Cadiz, Valencia Malaga, Cartegena, Las Palmas, Santa Cruz and Arrecife de Lanzarote; Portugal in the cities of Lisbon, Oporto Madeira, and St. Michaels; Cape Verde (former Portuguese territory) in the city of St. Vincent; Italy in the cities of Rome, Genoa, and Palermo; Netherland in the cities of Amsterdam and Dordrecht; Belgium in the cities of Antwerp, Ghent, Liege and Bruges; Sweden in the cities of Stockholm, Lyskil, and Gothemburg; Norway in the city of Oslo (formerly known as Kristiania); Denmark in the city of Copenhagen; and Japan in the city of Tokyo.

Hawai‘i War Crimes: Attempts to Denationalize the Inhabitants of an Occupied State

War crimes are actions taken by individuals, whether military or civilian, that violates international humanitarian law, which includes the 1907 Hague Conventions, 1949 Geneva Conventions and the Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions. War crimes include “grave breaches” of the 1949 Fourth Geneva Convention, which also applies to territory that is occupied even if the occupation takes place without resistance. Protected persons under International Humanitarian Law are all nationals who reside within an occupied State, except for the nationals of the Occupying Power. The International Criminal Court and States prosecute individuals for war crimes.

War Crimes: Attempts to Denationalize the Inhabitants of an Occupied State

The first instance of war crimes was brought up during World War I. In 1919, the Commission on Responsibilities of the Paris Peace Conference identified 32 war crimes, one of which was “attempts to denationalize the inhabitants of occupied territory.” The prosecution of German officials and their Allies for war crimes committed during World War I, however, was dismal. Of 5,000 individuals reported for war crimes only 12 were tried and 6 were convicted.

In October of 1943, the United States, the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union established the United Nations War Crimes Commission (UNWCC). World War II had been waging since 1939, and atrocities committed by Germany, Italy and Japan drew the attention of the Allies to hold individuals responsible for the commission of war crimes. On December 2, 1943, the UNWCC adopted the war crimes that were drawn up by the Commission on Responsibilities in 1919 with the addition of another war crime—indiscriminate mass arrests. The UNWCC was organized into three Committees: Committee I (facts and evidence), Committee II (enforcement), and Committee III (legal matters).

Committee III was asked to provide a report on war crime charges against four Italians accused of denationalization in Yugoslavia. The charge stated:

“Apart from killing, deportation and interning innocent persons, the Italians started a policy, on a vast scale, of denationalization. As a part of such a policy, they started a system of ‘re-education’ of Yugoslav children. This re-education consisted of forbidding children to use the Serbo-Croat language, to sing Yugoslav songs and forcing them to salute in a fascist way, become members of the G.I.L. (Gioventu italiana del Littoria) and spend a certain time in camps for ‘education.’ In all these actions aimed at the denationalization of Yugoslav children, Dr. Binna took a very active part. He brought Italian teachers from Italy and posted them all over the province of Zadar. Amongst those Italian teachers who insisted on the Italianization of Yugoslav children, BETTINI, Education Inspector and INCHIOSTRI, head-master of a secondary school at SIBENIK took a prominent part. Dr. Tulio NICOLETTI Trustee for Education at SIBENIK, and Edoardo CIUBELLI, Education Inspector at ZADAR, were also prominently associated with this policy. NICOLETTI organized special courses for teachers to learn Italian and Italian ‘methods’ and he threatened all those who would not attend the courses. Dr. BINNA is also responsible for forbidding the edition of any newspaper printed in the Serbo-Croat language, and for forcing Yugoslavs to hoist Italian flags.”

The question before Committee III was whether or not “denationalization” constituted a war crime that called for prosecution or merely a violation of international law. The Committee reported:

“It is the duty of belligerent occupants to respect, unless absolutely prevented, the laws in force in the country (Art. 43 of the Hague Regulations). Inter alia, family honour and rights and individual life must be respected (Art. 46). The right of a child to be educated in his own native language falls certainly within the rights protected by Article 46 (‘individual life’). Under Art. 56, the property of institutions dedicated to education is privileged. If the Hague Regulations afford particular protection to school buildings, it is certainly not too much to say that they thereby also imply protection for what is going to be done within those protected buildings. It would certainly be a mistaken interpretation of the Hague Regulations to suppose that while the use of Yugoslav school buildings for Yugoslav children is safe-guarded, it should be left to the unfettered discretion of the occupant to replace Yugoslav education by Italian education.”

“It is the rationale of Art. 56 to protect spiritual values. And in order to afford this protection to spiritual values the provision protects the property of institutions dedicated to public worship, charity, education, science and art as a means to a certain end; to make public worship, charity, education, science and art possible even under belligerent occupation. If the belligerent occupant must not confiscate, seize, destroy, or willfully damage the property of educational institutions, he is the less entitled to interfere with the spiritual and intellectual life of the schools, the only possible legitimate exception being considerations of the safety of the occupying forces.”

The Committee concluded:

“In the case of Nicoletti (No. 20) who is described as Educational Trustee, it appears that he was a kind of Commissioner in charge of the administration and Italianization of the schools in the district. In his case it seems to be conceivable to fasten upon him the individual responsibility for the whole Italianization scheme. The case of the three other persons who were mainly teaching personnel, seems prima facie to be different.”

Denationalization through Germanization was also taking place during World War II. “Within weeks of the fall of France, Alsace-Lorraine was annexed and thousands of citizens deemed too loyal to France, not to mention all its ‘alien-race’ Jews and North African residents, were unceremoniously deported to Vichy France, the southeastern section of the country still under French control. This was done in the now all too familiar manner: the deportees were given half an hour to pack and were deprived of most of their assets. By the end of July 1940, Alsace and Lorraine had become Reich provinces. The French administration was replaced and the French language totally prohibited in the schools. By 1941, the wearing of berets had been forbidden, children had to sing ‘Deutschland über Alles’ instead of ‘La Marseillaise’ at school, and racial screening was in full swing.” Lynn H. Nicholas, Cruel World: The Children of Europe in the Nazi Web (2005), 277.

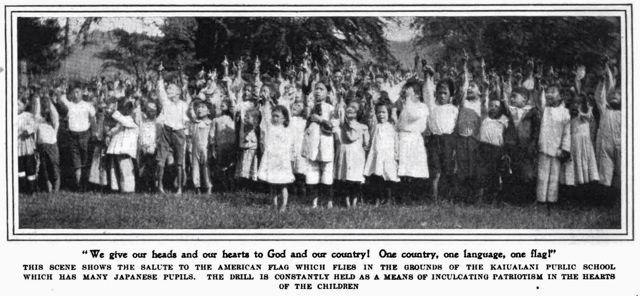

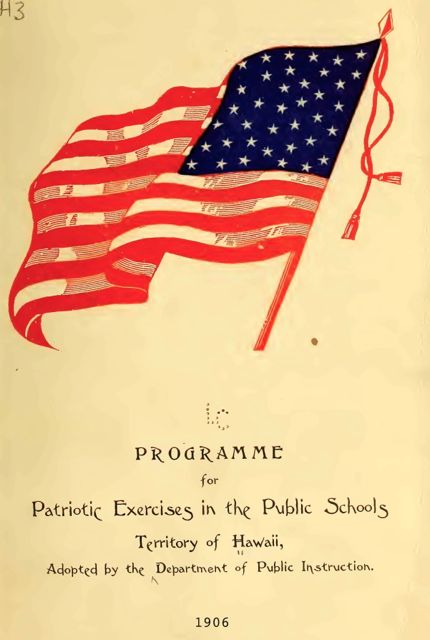

In 1906, the United States, as the occupying State, instituted a plan of Americanization in the Hawaiian Islands. The objective was to erase any and all national consciousness of the Hawaiian Kingdom amongst the school children in the Hawaiian Islands. The Hawaiian language was banned and American patriotism was taught in the public schools. The policy was established to counter the strong Hawaiian nationalism and opposition to American annexation as reported by the San Francisco Call newspaper, Strangling Hands Upon a Nation’s Throat (1897), Hawaii’s Last Struggle for Freedom (1897), and Passing of Hawaii as a Nation (1898). Americanization was carried out on a massive scale across the islands by inculcating American patriotism into the hearts of the school children and have them recite on a daily basis, ““We give our heads and our hearts to God and our Country! One Country! One Language! One Flag!”

In 1906, the United States, as the occupying State, instituted a plan of Americanization in the Hawaiian Islands. The objective was to erase any and all national consciousness of the Hawaiian Kingdom amongst the school children in the Hawaiian Islands. The Hawaiian language was banned and American patriotism was taught in the public schools. The policy was established to counter the strong Hawaiian nationalism and opposition to American annexation as reported by the San Francisco Call newspaper, Strangling Hands Upon a Nation’s Throat (1897), Hawaii’s Last Struggle for Freedom (1897), and Passing of Hawaii as a Nation (1898). Americanization was carried out on a massive scale across the islands by inculcating American patriotism into the hearts of the school children and have them recite on a daily basis, ““We give our heads and our hearts to God and our Country! One Country! One Language! One Flag!”

The policy of Americanization bore a striking resemblance to Italianization and Germanization that took place during World War II, but where the German and Italian occupations only lasted six years (1939-1945), the American occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom (1898-present) has gone uninterrupted for 116 years. What Germany and Italy failed to accomplish in six years, the United States was nearly successful at 116 years.

Today, there is no clear distinction made between the occupying State and the occupied State, as was the case between Yugoslavia and Italy or France and Germany during World War II. This was the case, however, when the United States military occupation began in 1898 during the Spanish-American War. But because of the prolonged nature of the occupation and the nearly successful program of denationalization, this clear distinction between the occupier and the occupied soon dissipated and our own people have unknowingly become the ones maintaining the policy of Americanization at the present.

The revitalization of the Hawaiian language and culture is in response to years of Americanization and the fact that the majority of the inhabitants of the Hawaiian Islands, to include the aboriginal Hawaiian, do not speak the Hawaiian language and know very little of Hawaiian culture is unequivocally the evidence of the war crime of “denationalization.”

The San Francisco Call: Hawaii’s Last Struggle for Freedom

In yesterday’s post “The San Francisco Call: Haywood Gratified, Mohailani Very Sad,” Mohailani appears to be a pseudo name, which is literally translated to “great sacrifice.” It was an emotional and comprehensive response of a bereaved person or persons. It is clear that the San Francisco Call knew whom to contact for responses and that “Mohailani” was someone that the Call was already familiar with.

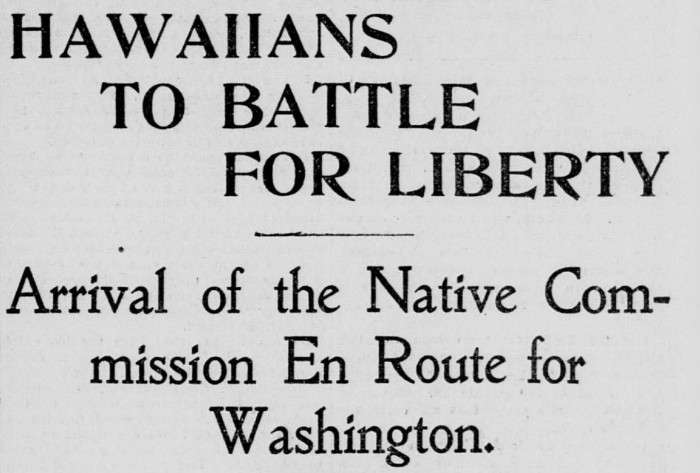

The tenor of Mohailani’s response was definitely from someone who was already familiar with the Hawaiian opposition to annexation that included not just the men but also the women. This appears to point to the San Francisco Call’s coverage of the Hawaiian Patriotic League “Strangling Hands on a Nation’s Throat,” published September 30, 1897, and “Hawaii’s Last Struggle for Freedom,” published November 28, 1897. Both stories centered on a petition of over 21,000 signatures protesting annexation that was gathered by the Hawaiian Patriotic League.

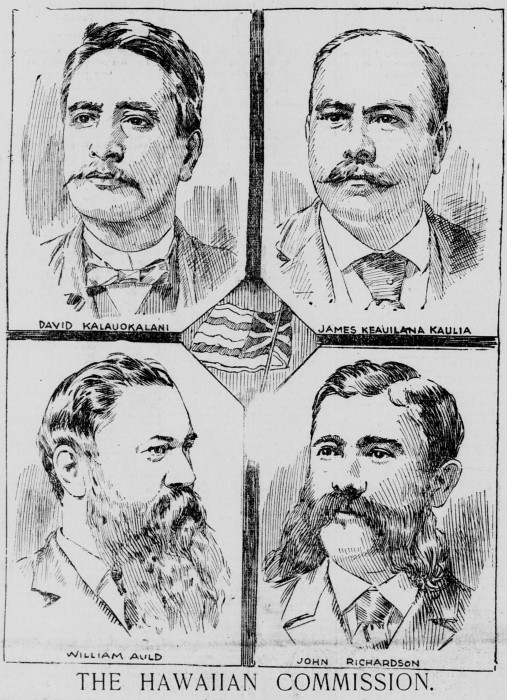

The last story centered on a Hawaiian Commission that arrived in San Francisco on their way to Washington, D.C. James Kaulia, President of the Hawaiian Patriotic League, led a Hawaiian Commission of four men in order to present the signature petition to the United States Senate when it convened in December of 1897.

Could it be that “Mohailani” was the collective pseudo name for the Hawaiian Commission especially their stated loathe for Senator Morgan?

*************************************

Hawaii has sent four of her representative men to plead wit the United States before annexation is consummated. These men, forming a committee unique in the history of modern nations, have arrived in San Francisco. On Monday they will proceed to Washington.

The committee consists of two full-blooded Hawaiians and two half-Hawaiians. The leader of the delegation is Mr. James K. Kaulia, the president of the Hawaiian Patriotic League. There are, besides, Mr. David Kalauokalani, the leader of the second Hawaiian society, which differs only in its opinion on local matters from the Patriotic League; Mr. William Auld, who is a possessor of considerable property on the island of Oahu, and Mr. John Richardson, a lawyer from the island of Maui, whose command of English, as well as his ability as a lawyer, makes him the spokesman of the party.

Mr. Richardson and Mr. Kaulia were interviewed by the The Call yesterday upon their mission.

“We are going to Washington,” said Mr. Richardson, “with the hope of inducing the President and the Committee on Foreign Relations to listen to our side of the question. From documents in our possession we think we can convince any fair-minded man that the great majority of the natives of Hawaii are opposed to annexation. If, from our showing, the United States is not assured of this fact, we shall ask that a vote be taken.”

“A secret ballot?”

Mr. Richardson threw open his arms. “It doesn’t matter. Even if the ballot be open the very men who have refused to sign our memorial will vote against annexation.”

“Then some Hawaiians have refused to sign the petition against annexation?”

Mr. Kaulia, who had sat listening quietly, his grave face and dark eyes turned upon his more vivacious colleague, spoke now.

“Nearly twenty-one thousand Hawaiians have signed the memorial we are taking to Washington. The men, the natives, who have refused to sign, tell us that it would hurt their business or jeopardize their positions if their names were added to our petition. But they are with us in feeling, and as John—Mr. Richardson—says, if it comes to a vote, they will forget every other consideration, and remember only that their country is being taken from them.”

“Your committee has been sent to Washington by the Hawaiians.”

“Yes, we four have been chosen to speak for Hawaii,” said Mr. Richardson. “The natives have subscribed liberally to the fund which pays our expenses. Maui, the island of Maui, is the leader in this. At first the Hawaiians would not believe that there was really any danger of annexation. But on Maui—Maui is a unit on anti-annexation sentiment—we insisted that a delegation be sent. You know the native didn’t believe it possible that the United States would annex the islands, knowing the opposition of the Hawaiians. They wouldn’t believe that things could go so far.”

“And what is their opinion now?”

“Now they are thoroughly awakened to the danger. But they are hopeful—”

“The United States cannot,” interrupted Mr. Kaulia, “if it has any regard for justice, annex our country, after our protest. We have come to make known how the natives feel in the matter. I tried to see Senator Morgan when he was in Honolulu. Twice I wrote asking him when he could see me, when he could listen to us—he had listened long to the annexationists—but I received no answer. The natives are very bitter in their dislike of him, for they know how determined he is on annexation.”

“But there is considerable opposition,” said Mr. Richardson. “Senators Du Boise and Pittigrew, who came upon on the same steamer with us, have spent ten days on the islands. They see and admit the injustice that would be done the Hawaiians if their country were taken from them. Senator Du Boise says that he hasn’t met one native Hawaiian who is in favor of annexation, and he went as far as the island of Hawaii. He didn’t remain in Honolulu.”

“In case, though, of annexation, what will the Hawaiians do?”

Mr. Richardson spoke very seriously. “If the people of the United States take Hawaii the natives will have to kept down by force—as they are now.”

“We hope to convince your Government that the Government of the Islands was overthrown by means of American warships; that the present is not a representative Government, and that the Hawaiians will never be reconciled to the loss of nationality.”

“The members of the administration are doing everything in their power to bring about annexation. If they learn that they are not likely to succeed in this way they will try another. They will do as they did before—declare that their lives and property are in danger and ask that the American flag be raised. And we know, we Hawaiians, that if the flag goes up again it will never come down.”

“But what will you do about it?” Mr. Richardson was asked.

“We will fight,” he answered determinedly. “We will turn upon the administration, and we will fight before we let that flag go up again.”

“The Hawaiians are very peaceable people—very easy going and good natured. They do not become angry easily. It takes a great deal to rouse them. But they are roused now. They recognize that if resistance is to be made it must be now. They can fight—they will fight rather than allow their land, their own country, to be taken from them.”

The San Francisco Call: Haywood Gratified, Mohailani Very Sad

This article in the San Francisco Call newspaper was sent by Willy Kauai, a doctoral candidate in Political Science at the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa. Kauai’s doctoral research centers on Hawaiian nationality or citizenship, which spans from its origin under the reign of King Kamehameha I, progenitor of the Hawaiian Kingdom, through its legal evolution during the 19th century, and its maintenance under the laws of occupation to date.

Kauai’s research also addresses the racial discrimination injected into the population of the Hawaiian Islands since the usurpers seized temporary control of the Hawaiian government in 1887, which served as the precursor to the United States invasion and unlawful overthrow of the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and the ultimate occupation since the Spanish-America War in 1898. The title of Kauai’s dissertation is “E/racing Hawaiian Citizenship Amid US Occupation.” Kauai will be defending his dissertation in April 2014 and is expected to graduate the following month with his Ph.D. degree.

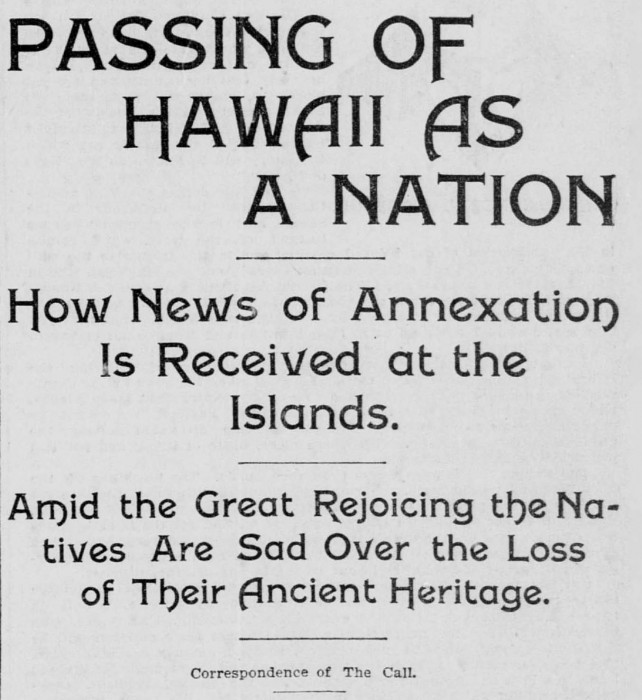

On July 28, 1898, the San Francisco Call newspaper published responses by individuals in the Hawaiian Islands as to their reaction to the passing of the joint resolution by the United States Congress to annex the Hawaiian Islands titled “Passing of Hawaii as a Nation: How News of Annexation is Received at the Islands.” One particular response was titled “Haywood Gratified, Mohailani Very Sad.” Just ten months earlier, the San Francisco Call published a front-page story covering Hawaiian opposition to annexation titled, “Strangling Hands Upon a Nation’s Throat.” As a result of this opposition the United States Senate was unable to ratify a so-called treaty of annexation signed between the insurgents and the McKinley administration. Unable to accomplish the task by treaty, annexationists in the Congress introduced a joint resolution, instead. The Congress knew that a joint resolution, being a Congressional law, had no force beyond the borders of the United States, but they disguised the process as if it did, through propaganda, in order to conceal an illegal occupation of a foreign State for military purposes.

*************************************

HONOLULU, July 20.—“I am naturally gratified that annexation has at last been accomplished,” said Consul General Haywood when the news of annexation reached him. “It is what I came to these islands to see done, and I am glad I have not had to go home disappointed. The United States has given to the people of these islands what I consider to be the greatest gift they could receive—American citizenship—which carries with it stable government and protection from the nations of the world. It only remains with the people here to make the most of the gift. This can only be done by forgetting past animosities and working harmoniously for the public good. Americans will then make of these islands not merely the paradise of the Pacific, but the Paradise of the world.”

HONOLULU, July 20.—“I am naturally gratified that annexation has at last been accomplished,” said Consul General Haywood when the news of annexation reached him. “It is what I came to these islands to see done, and I am glad I have not had to go home disappointed. The United States has given to the people of these islands what I consider to be the greatest gift they could receive—American citizenship—which carries with it stable government and protection from the nations of the world. It only remains with the people here to make the most of the gift. This can only be done by forgetting past animosities and working harmoniously for the public good. Americans will then make of these islands not merely the paradise of the Pacific, but the Paradise of the world.”

HONOLULU, July 20.—To the Editor of the San Francisco Call: You ask me how we Hawaiians have received the news which has deprived us of our country and our nationality. I can only say that my countrymen are yet unable to realize the fact that the great republic which boasts of its democratic and republican principles has committed the unholy act which in history will be known as the “Rape of Hawaii.”

We had hoped that the joint resolution would be defeated in the Senate, and we were stunned when we learned of the vote, which results in the annihilation of our beloved country and in the driving to the wall of all Hawaiians. I can assure you that there is not one Hawaiian who in his heart favors annexation. What would you think of any man or woman who with indifference could see the flag of his or her country go down and their individually absorbed by a foreign race which, whatever you may say, does look down on us as their inferiors and despises our color and our way of living?

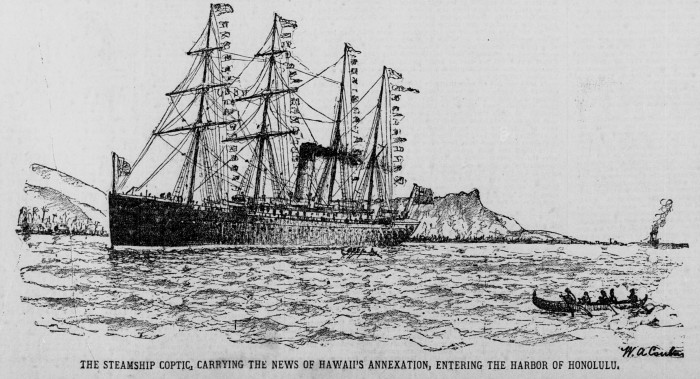

I can tell you, and few men have the opportunity of knowing the Hawaiians as I do, that many tears were shed when the news by the Coptic reached the homes of those who know no other country than these islands, which once were justly called the Paradise of the Pacific. We cannot be happy under our new conditions. We will feel like strangers among the people who will rule us, and with whose ideas, mode of living and political principles we cannot harmonize.

Our women feel it even worse than we men do. The teachings of the New England missionaries, the rum they brought with them, the diseases following in their train, have enervated the Hawaiian men. We can talk, don’t you forget it, but we cannot fight. If we had yet the fighting qualities of our ancestors, the overturn of our monarchy would never have taken place, and during the past years we would have been entitled to interference in the name of humanity in our struggles against the usurpers.

Our women have shown more energy, more solid patriotism and more strength than we have. The women of Hawaii to-day stand as a unit in their hatred toward America and everything American. And can you blame them? They see before them a future where their children will be forced into competition with your pushing, rushing, money-grabbing race. The dolce far niente of Hawaii must disappear and the struggle for life will begin in which the strongest will survive, and the gentle, indolent, easy-going Hawaiian will have no show in that battle for life, and who can blame us for feeling sad over a future which necessarily means destruction of our race?

I cannot deny that one great reason for our opposition to annexation is that we fear that we will be called “niggers” and treated as you do that class in your “free” country. We have been assured that such will not be the case, but experience tells us differently. Our countrymen who have traveled in the States have often been subjected to great humiliation and insult on account of their skin, and we expect that the day will come when we will risk similar affronts right in our streets, and remember that we have neither the wealth nor the inclination to strike our tents in other climes. We have no other home than Hawaii, and that home we have lost.

And what will our position be in the political and social life of these islands after your flag floats over the palace of our chiefs?

Senator Morgan of Alabama told a large assembly of Hawaiians, when he visited here, that he could promise them equal political rights with any American in any State of America. He told us that each of us would have as good a chance to become President of the United States as has Grover Cleveland. (I believe him in that.) He said that Hawaii would be a State, and that by the power of our majority we would control the affairs of Hawaii and enjoy true self-government. He paid a glowing tribute to our intelligence and excellent qualities, and told us how he loved “colored” people.

We didn’t believe a word of what that ex-slave driver from Alabama said, and there is no man more despised and loathed among the Hawaiians than Senator Morgan, who now is to frame a government for Hawaii.

The Hawaiians have at present no intention of taking any active interest in the government of their country. They feel like the children of Israel did when they sat down in exile and bemoaned their fate. What has happened cannot be undone, but none of us can see what your great country has gained by adding to the Union such unwilling and hostile people. We are not savages, as your Indians of Alaska, or ignorant as your “greasers.” For nearly a century we have conducted a fairly good government and lived in harmony with the white man who benefited from our hospitality and whose descendants now rob us of our country.

Go ask any man, woman or child what he thinks to-day of the “haole” (the foreigner), and you will get an answer in a very emphatic and plain language.

When Chinese and Japanese coolies are stopped from coming here as contract laborers we will have the satisfaction of laughing at the men who make their money out of slave labor and who brought on annexation to gain the benefit of the sugar bounty. But that satisfaction is very slim when we realize the fact that we will be trodden under foot by the invaders, and that when your flag, which we admire in its proper place, waves over Hawaii, to pronounce the fact that we are homeless and that our country has ceased to exist.

MOHAILANI

(It is not known who Mohailani is, but Hawaiians were known for using a pseudo name when authoring commentaries of a political nature. “Mohailani” is literally translated in the Hawaiian language as the “GREAT SACRIFICE.”)

Hawai‘i War Crimes: Destroying or seizing the Occupied State’s property

War crimes are actions taken by individuals, whether military or civilian, that violates international humanitarian law, which includes the 1907 Hague Conventions, 1949 Geneva Conventions and the Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions. War crimes include “grave breaches” of the 1949 Fourth Geneva Convention, which also applies to territory that is occupied even if the occupation takes place without resistance. Protected persons under International Humanitarian Law are all nationals who reside within an occupied State, except for the nationals of the Occupying Power. The International Criminal Court and States prosecute individuals for war crimes.

War Crimes: Destroying or seizing the [Occupied State’s] property unless such destruction or seizure be imperatively demanded by the necessities of war

On August 12, 1898, the United States of America seized approximately 1.8 million acres of land that belonged to the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom and to the office of the Monarch. These lands were called Government lands and Crown lands, respectively, whereby the former being public lands and the latter private lands. These combined lands constituted nearly half of the entire territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

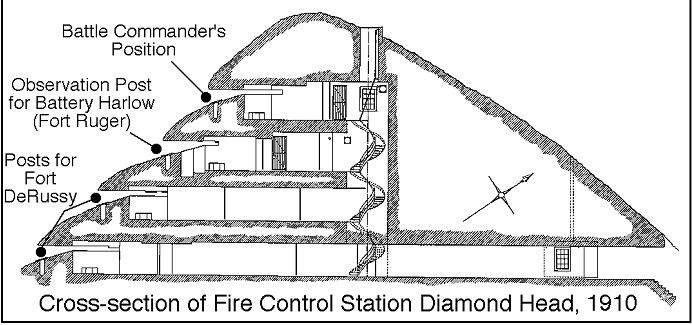

Beginning on July 20, 1899, President McKinley began to set aside portions of these lands by executive orders for “installation of shore batteries and the construction of forts and barracks.” Below are the schematics for defense of the popularly known Diamond Head crater at Waikiki.

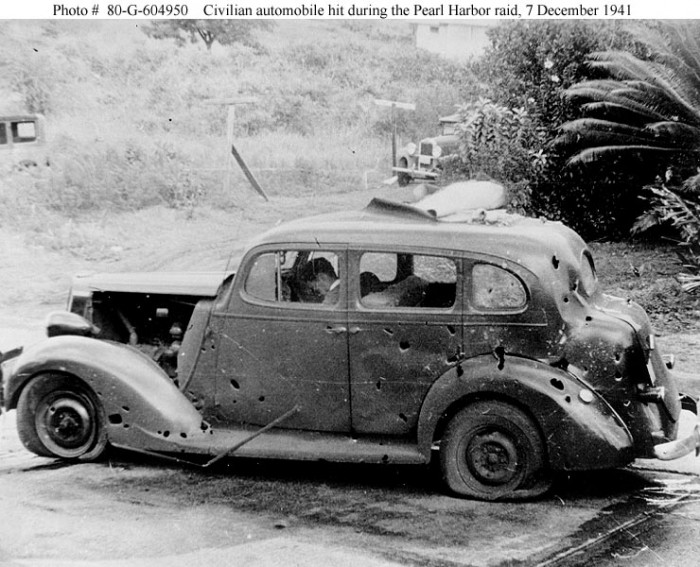

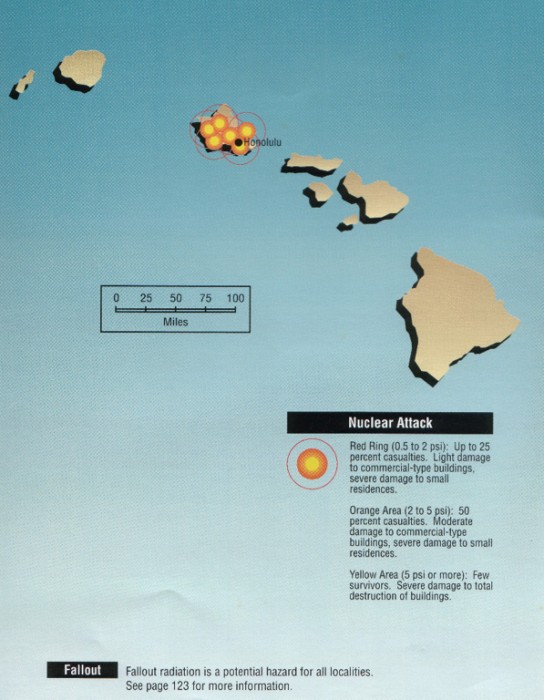

The first executive order set aside 15,000 acres for two Army military posts on the Island of O‘ahu called Schofield Barracks and Fort Shafter. According to Van Brackle’s “Pearl  Harbor from the First Mention of ‘Pearl Lochs’ to Its Present Day Usage,” this soon followed the securing of lands for Pearl Harbor naval base in 1901 when the U.S. Congress appropriated funds for condemnation of 719 acres of private lands surrounding Pearl River, which later came to be known as Pearl Harbor. By 2012, the U.S. military has 118 military sites that span 230,929 acres of the Hawaiian Islands, which is 20% of the total acreage of Hawaiian territory.

Harbor from the First Mention of ‘Pearl Lochs’ to Its Present Day Usage,” this soon followed the securing of lands for Pearl Harbor naval base in 1901 when the U.S. Congress appropriated funds for condemnation of 719 acres of private lands surrounding Pearl River, which later came to be known as Pearl Harbor. By 2012, the U.S. military has 118 military sites that span 230,929 acres of the Hawaiian Islands, which is 20% of the total acreage of Hawaiian territory.

Military training locations include Pacific Missile Range Facility, Barking Sands Tactical Underwater Range, and Barking Sands Underwater Range Expansion on the Island of Kaua‘i; the entire Islands of Ni‘ihau and Ka‘ula; Pearl Harbor, Lima Landing, Pu‘uloa Underwater Range—Pearl Harbor, Barbers Point Underwater Range, Coast Guard AS Barbers Point/Kalaeloa Airport, Marine Corps Base Hawai‘i, Marine Corps Training Area Bellows, Hickam Air Force Base, Kahuku Training Area, Makua Military Reservation, Dillingham Military Reservation, Wheeler Army Airfield, and Schofield Barracks on the Island of O‘ahu; and Bradshaw Army Airfield and Pohakuloa Training Area on the Island of Hawai‘i.

The United States Navy’s Pacific Fleet headquartered at Pearl Harbor hosts the Rim of the Pacific Exercise (RIMPAC) every other even numbered year, which is the largest international maritime warfare exercise. RIMPAC is a multinational, sea control and power projection exercise that collectively consists of activity by the U.S. Army, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Naval forces, as well as military forces from other foreign States. During the month long exercise, RIMPAC training events and live fire exercises occur in open-ocean and at the military training locations throughout the Hawaiian Islands. In 2012, Australia, Canada, Chile, Colombia, France, India, Indonesia, Japan, Mexico, Malaysia, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Peru, Philippines, Russia, Singapore and South Korea participated in the RIMPAC exercises.