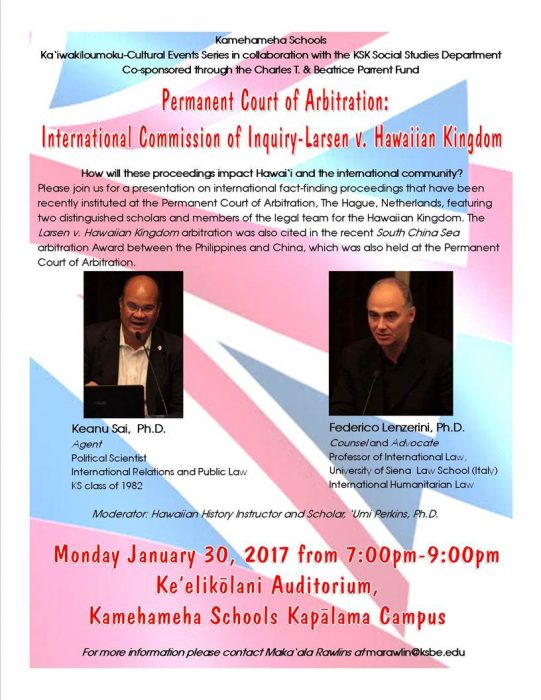

As the Tribunal at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom pointed out in, “in the nineteenth century the Hawaiian Kingdom existed as an independent State recognized as such by the United States of America, the United Kingdom and various other States, including by exchanges of diplomatic or consular representatives and the conclusion of treaties.” (Award, Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, 119 International Law Reports (2001) 581). As an independent State, the Hawaiian Kingdom was a member of the Family of Nations along with other independent States including the United States. According to Westlake in 1894, they comprised, “First, all European States […] Secondly, all American States […] Thirdly, a few Christian States in other parts of the world, as the Hawaiian Islands, Liberia and the Orange Free State.” (John Westlake, Chapters on the Principles of International Law (1894) 81).

In 1893, there were 44 independent and sovereign States in the Family of Nations: Argentina, Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Bolivia, Brazil, Bulgaria, Chili, Colombia, Costa Rica, Denmark, Ecuador, France, Germany, Great Britain, Greece, Guatemala, Hawaiian Kingdom, Haiti, Honduras, Italy, Liberia, Lichtenstein, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Mexico, Monaco, Montenegro, Nicaragua, Orange Free State that was later annexed by Great Britain in 1900, Paraguay, Peru, Portugal, Romania, Russia, San Domingo, San Salvador, Serbia, Spain, Sweden-Norway, Switzerland, Turkey, United States of America, Uruguay, and Venezuela. In 1945, there were 45, and today there are 193.

From a State of Peace to a State of War—No Middle Ground

International law, which is law between nations, formed the protocol and relations between these member States. “Traditional international law was based upon a rigid distinction between the state of peace and the state of war,” states Judge Greenwood (Christopher Greenwood, “Scope of Application of Humanitarian Law,” in Dieter Fleck (ed), The Handbook of the International Law of Military Operations (2nd ed., 2008) 45). “Countries were either in a state of peace or a state of war; there was no intermediate state.” (Ibid.) This is also reflected by the fact that the renowned jurist of international law, Lassa Oppenheim, separates his treatise on International Law into two volumes, Vol. I—Peace, and Vol. II—War and Neutrality.

Throughout the nineteenth century, the Hawaiian Kingdom was not only independent and sovereign, but also a neutral State explicitly recognized by treaties with Germany, Spain and Sweden-Norway. The Hawaiian Kingdom enjoyed a state of peace with all States. This status of affairs, however, was interrupted by the United States when the state of peace was transformed to a state of war that began on January 16, 1893. On January 17, 1893, Queen Lili‘uokalani, the Executive Monarch of the Hawaiian Kingdom, made the following protest and a conditional yielding of her authority to the President of the United States in response to military action taken against the Hawaiian government by order of the U.S. resident diplomat John Stevens. The Queen’s protest stated:

“I, Liliuokalani, by the grace of God and under the constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Queen, do hereby solemnly protest against any and all acts done against myself and the constitutional Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom by certain persons claiming to have established a provisional government of and for this Kingdom. That I yield to the superior force of the United States of America, whose minister plenipotentiary, His Excellency John L. Stevens, has caused United States troops to be landed at Honolulu and declared that he would support the said provisional government. Now, to avoid any collision of armed forces and perhaps the loss of life, I do, under this protest, and impelled by said force, yield my authority until such time as the Government of the United States shall, upon the facts being presented to it, undo the action of its representatives and reinstate me in the authority which I claim as the constitutional sovereign of the Hawaiian Islands.” (Annexure 2, Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, 119 International Law Reports (2001) 612).

Under international law, the landing of American troops without the consent of the Hawaiian government was an act of war. But in order for an act of war to transform the status of affairs to a state of war, the act must be unlawful under international law. In other words, an act of war would not change the status of affairs to a state of war from that of peace if the action were legal under international law. According to Professor Wright, “An act of war is an invasion of territory…and so normally illegal. Such an act if not followed by war gives grounds for a claim which can be legally avoided only by proof of some special treaty or necessity justifying the act.” (Quincy Wright, “Changes in the Concept of War,” 18 American Journal of International Law (1924), 756).

Military action in a foreign State considered lawful under international law, includes proportionate reprisals in response to another State’s action just short of all out war, and military actions taken to protect its citizenry in the foreign State. Furthermore, the act of war must have been intentional—animo belligerendi, to overthrow the government of the invaded State. As international law is a law between States, which derives from agreements, the claim made by Queen Lili‘uokalani that United States troops unlawfully invaded the kingdom had to be acknowledged by the President of the United States as true. In her protest she called upon the President to investigate the facts and then “undo the action of its representatives and reinstate me in the authority which I claim as the constitutional sovereign of the Hawaiian Islands.” In international law, this is called restitutio in integrum.

After ten months of investigating the overthrow, President Cleveland notified the Congress on December 18, 1893, that the “military demonstration upon the soil of Honolulu was of itself and act of war” that could not be justified under international law as “either with the consent of the Government of Hawaii or for the bona fide purpose of protecting the imperiled lives and property of citizens of the United States.” (Annexure 1—President Cleveland’s message to the Senate and House of Representatives dated 18 December 1893, Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, 119 International Law Reports (2001) 604).

The President then concluded, “By an act of war, committed with the participation of a diplomatic representative of the United States and without authority of Congress, the Government of a feeble but friendly and confiding people has been overthrown.” (Ibid, 608). He notified the Congress that he initiated negotiations with the Queen “to aid in the restoration of the status existing before the lawless landing of the United States forces at Honolulu on the 16th of January last, if such restoration could be effected upon terms providing for clemency as well as justice to all parties concerned.” (Ibid, 610). What Cleveland did not know at the time of his message to the Congress was that the Queen, on the very same day in Honolulu, accepted the conditions for settlement in an attempt to return to a state of peace. The executive mediation began on November 13, 1893 between the Queen and U.S. diplomat Albert Willis. The President was not aware of the agreement until January 12, 1894.

Despite being unaware of the agreement to settle, President Cleveland’s political determination was an acknowledgment that the United States was in a state of war with the Hawaiian Kingdom since the invasion occurred on January 16, 1893, as stated by the Queen in her protest on January 17, 1893. International law defines war as “a contention between States for the purpose of overpowering each other.” (L. Oppenheim, International Law, vol. II—War and Neutrality (3rd ed., 1921) 74).

Once a state of war ensued between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States, “the law of peace ceased to apply between them and their relations with one another became subject to the laws of war, while their relations with other states not party to the conflict became governed by the law of neutrality.” (Greenwood, 45). This outbreak of a state of war between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States would “lead to many rules of the ordinary law of peace being superseded…by rules of humanitarian law.” (Ibid, 46).

A state of war “automatically brings about the full operation of all the rules of war and neutrality.” (Myers S. McDougal, “The Initiation of Coercion: A Multi-temporal Analysis,” 52 American Journal of International Law (1948) 247). And according to Venturini, “If an armed conflict occurs, the law of armed conflict must be applied from the beginning until the end, when the law of peace resumes in full effect.” (Gabriella Venturini, “The Temporal Scope of Application of the Conventions,” in Andrew Clapham, Paola Gaeta, and Marco Sassòli (eds), The 1949 Geneva Conventions: A Commentary (2015), 52). Only by a treaty or agreement between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States could a state of peace be restored, without which a state of war ensues.

In order to transform the state of war to a state of peace an attempt was made by executive agreement entered into between President Cleveland, by his resident diplomat Albert Willis, and Queen Lili‘uokalani in Honolulu on December 18, 1893 (David Keanu Sai, “A Slippery Path Towards Hawaiian Indigeneity: An Analysis and Comparison between Hawaiian State Sovereignty and Hawaiian Indigeneity and Its Use and Practice Today,” 10 Journal of Law and Social Challenges (2008) 119-127). Cleveland, however, was unable to carry out his duties and obligations to restore the situation that existed before the unlawful landing of American troops due to political wrangling in the Congress. The state of war continued.

It is a common misconception that only through a declaration of war by the Congress could a state of war exist for the United States. A Federal court in 1946, however, dispensed with this theory in New York Life Ins. Co. v. Bennion. The Court stated, “it cannot be denied that the acts and conduct of the President, acting in furtherance of his constitutional authority and duty, would constitute a political determination of a state of war of which the courts would take judicial notice. We can discern no demonstrable difference in the supposition and the actual facts, and we therefore conclude that the formal declaration by the Congress on December 8th was not an essential prerequisite to a political determination of the existence of a state of war commencing with the attack on Pearl Harbor [on December 7th].” (New York Life Ins. Co. v. Bennion, 158 F.2d 260 (C.C.A. 10th, 1946), 41 American Journal of International Law (1947), 682).

Therefore, the conclusion reached by President Cleveland that an act of war had been committed by the United States was a “political determination of the existence of a state of war,” and that a formal declaration of war by the Congress was not essential. The “political determination” by President Cleveland regarding the actions taken by the military forces of the United States on January 16, 1893, was the same as the “political determination” by President Roosevelt regarding actions taken by the military forces of Japan on December 7, 1945. Both “political determinations,” being acts of war, created a state of war for the United States. A declaration of war by the Congress was not essential in both situations.

The Duty of Neutrality by Third States

When the President declared that a state of war existed by an act of war committed by the American military in his message to Congress, all of the other 42 States were under a duty of neutrality. “Since neutrality is an attitude of impartiality, it excludes such assistance and succour to one of the belligerents as is detrimental to the other, and, further such injuries to the one as benefit the other.” (L. Oppenheim, International Law, vol. II—War and Neutrality (3rd ed., 1921) 401).

The duty of a neutral State, not a party to the conflict, “obliges him, in the first instance, to prevent with the means at his disposal the belligerent concerned from committing such a violation,” e.g. to deny recognition of a puppet government unlawfully created by an act of war. (Ibid, 496). Twenty of these States violated their obligation of impartiality by recognizing the so-called Republic of Hawai‘i, a United States puppet government created by an act of war committed by the United States on January 17, 1893. These States include:

- Austria-Hungary (January 1, 1895);

- Belgium (October 17, 1894);

- Brazil (September 29, 1894);

- Chile (September 26, 1894);

- China (October 22, 1894);

- France (August 31, 1894);

- Germany (October 4, 1894);

- Guatemala (September 30, 1894);

- Italy (September 23, 1894);

- Japan (April 6, 1897);

- Mexico (August 8, 1894);

- Netherlands (November 2, 1894);

- Norway-Sweden (December 17, 1894);

- Peru (September 10, 1894);

- Portugal (December 17, 1894);

- Russia (August 26, 1894);

- Spain (November 26, 1894);

- Switzerland (September 18, 1894); and

- United Kingdom (September 19, 1894).

“If a neutral neglects this obligation, he himself thereby commits a violation of neutrality, for which he may be made responsible by a belligerent who has suffered through the violation of neutrality committed by the other belligerent and acquiesced in by him.” (Ibid, 497). The recognition of the so-called Republic of Hawai‘i did not create any legality or lawfulness on the part of the puppet regime, but rather is the indisputable evidence that these States’ violated their duty to be neutral. Diplomatic recognition of governments occurs during a state of peace and not during a state of war, unless providing recognition of belligerency status. The recognitions were not recognizing the Republic as a belligerent in a civil war with the Hawaiian Kingdom, but rather under the false pretense that the Republic succeeded in a revolution and therefore was the new government of Hawai‘i during a state of peace. As such, their relationship with the Hawaiian Kingdom has since been regulated by humanitarian law.

State of War—No Question

The state of war has ensued to date, only to be concealed by a false narrative promoted by the United States government that Hawai‘i was purportedly annexed in 1898 through American legislation (Sai, Slippery Path, 84-94), coupled with a formal policy of the war crime of denationalizing school children beginning in 1906. The purpose of the policy was to obliterate the national consciousness of the Hawaiian Kingdom in the minds of the children and replace it with American patriotism. Within three generations, the effect of the denationalization was nearly complete.

The Hawaiian Kingdom has been in a “legal” state of war with the United States for over a century and the application of the laws of occupation and applicable humanitarian law has not diminished. Without a treaty between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States to return the state of affairs back to a state of peace, the state of war continues. As Judge Greenwood stated, “Countries were either in a state of peace or a state of war; there was no intermediate state.”

This is the longest state of war ever to have taken place in the history of international relations, which has created a humanitarian crisis of unimaginable proportions. International humanitarian laws apply, which includes customary international law regarding war and neutrality, 1907 Hague Regulations and the 1949 Geneva Conventions.