Category Archives: Education

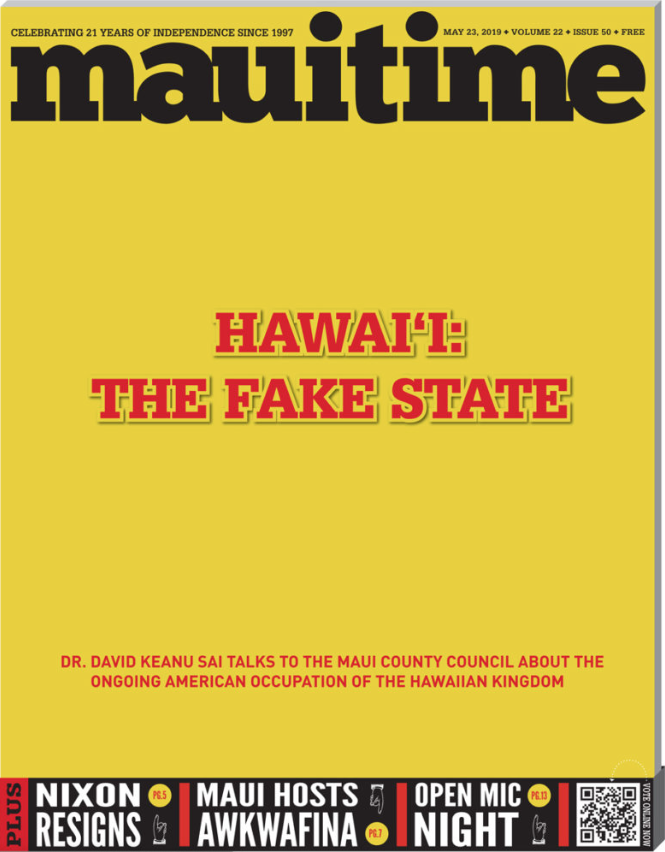

Video of Dr. Keanu Sai’s Presentation to the Maui County Council on the status of the Hawaiian Kingdom under International Law

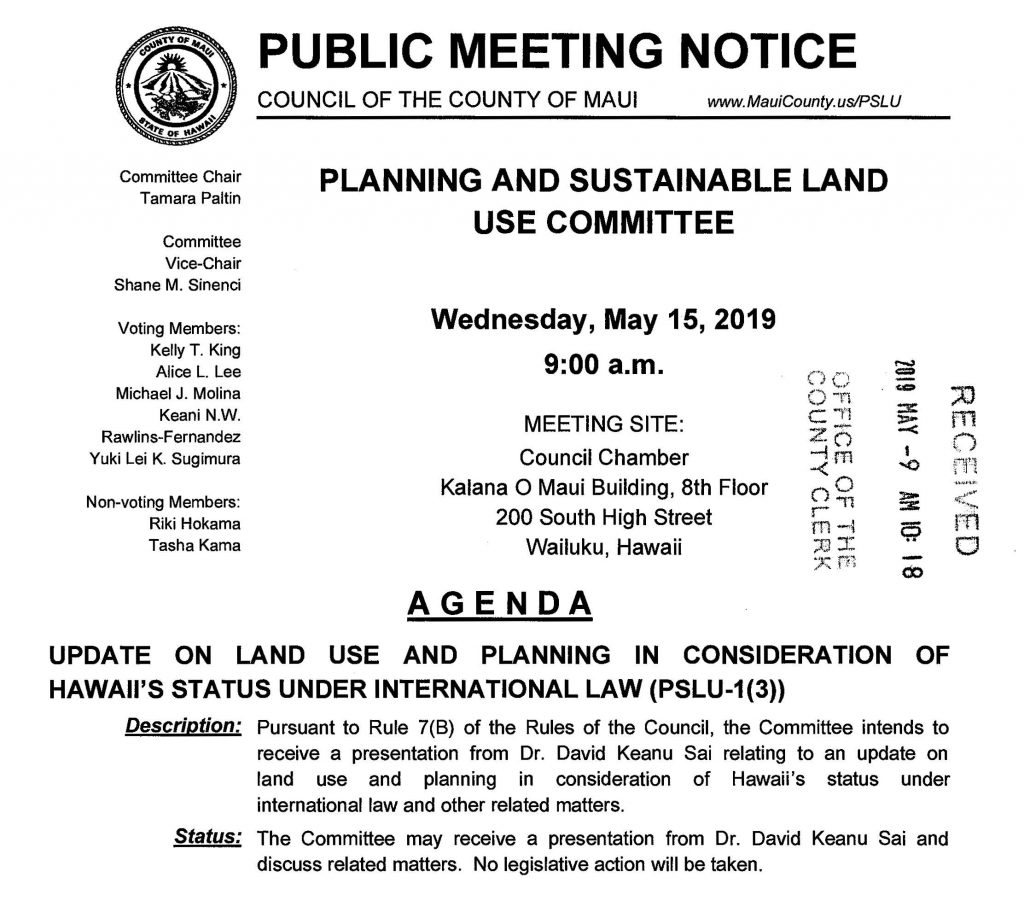

Dr. Keanu Sai to Present to Maui County Council May 15, 2019

New Documentary: Speaking Truth to Power

Investigating the Illegal U.S. Military Occupation of the Hawaiian Islands

From Integrative Media Co-operative (IMC):

IMC would like to continue documenting up and coming events and actions regarding the U.S. military occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom. IMC relies on public donations. To donate visit IMC’s Indiegogo crowdfunding campaign: Speaking Truth to Power – Documentary. Or contact IMC directly at integrative.media.coop@gmail.com.

Please subscribe to IMC’s YouTube channel, Integrative Media Co-operative, to stay updated on future projects. There are many short videos coming soon regarding this topic.

Most importantly, sharing this video with friends and family brings a greater awareness to this ongoing and evolving situation.

126 Years Ago Today: U.S. Invasion of Hawai‘i

Status of the Hawaiian Kingdom under International Law

In 2001, the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s arbitral tribunal, in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, declared “in the nineteenth century the Hawaiian Kingdom existed as an independent State recognized as such by the United States of America, the United Kingdom and various other States, including by exchanges of diplomatic or consular representatives and the conclusion of treaties (paragraph 7.4).” The terms State and Country are synonymous.

As an independent State, the Hawaiian Kingdom entered into extensive treaty relations with a variety of States establishing diplomatic relations and trade agreements. The Hawaiian Kingdom entered into three treaties with the United States: 1849 Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation; 1875 Commercial Treaty of Reciprocity; and 1883 Convention Concerning the Exchange of Money Orders. In 1893 there were only 44 independent and sovereign States, which included the Hawaiian Kingdom, as compared to 197 today.

On January 1, 1882, it joined the Universal Postal Union. Founded in 1874, the UPU was a forerunner of the United Nations as an organization of member States. Today the UPU is presently a specialized agency of the United Nations.

By 1893, the Hawaiian Kingdom maintained over ninety Legations and Consulates throughout the world. In the United States of America, the Hawaiian Kingdom manned a diplomatic post called a legation in Washington, D.C., which served in the same function as an embassy today, and consulates in the cities of New York, San Francisco, Philadelphia, San Diego, Boston, Portland, Port Townsend and Seattle. The United States manned a legation in Honolulu, and consulates in the cities of Honolulu, Hilo, Kahului and Mahukona.

“Traditional international law was based upon a rigid distinction between the state of peace and the state of war (p. 45),” says Judge Greenwood in his article “Scope of Application of Humanitarian Law” in The Handbook of the International Law of Military Occupations (2nd ed., 2008), “Countries were either in a state of peace or a state of war; there was no intermediate state (Id.).” This is also reflected by the fact that the renowned jurist of international law, Professor Lassa Oppenheim, separated his treatise on International Law into two volumes, Vol. I—Peace, and Vol. II—War and Neutrality.

Presidential Investigation of the Overthrow of the Hawaiian Government

On January 16, 1893, United States troops invaded the Hawaiian Kingdom without just cause, which led to a conditional surrender by the Hawaiian Kingdom’s executive monarch, Her Majesty Queen Lili‘uokalani, the following day. Her conditional surrender read:

“I, Liliuokalani, by the grace of God and under the constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Queen, do hereby solemnly protest against any and all acts done against myself and the constitutional Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom by certain persons claiming to have established a provisional government of and for this Kingdom.

That I yield to the superior force of the United States of America, whose minister plenipotentiary, His Excellency John L. Stevens, has caused United States troops to be landed at Honolulu and declared that he would support the said provisional government.

Now, to avoid any collision of armed forces and perhaps the loss of life, I do, under this protest, and impelled by said force, yield my authority until such time as the Government of the United States shall, upon the facts being presented to it, undo the action of its representatives and reinstate me in the authority which I claim as the constitutional sovereign of the Hawaiian Islands.”

In response to the Queen’s conditional surrender of her authority, President Grover Cleveland initiated an investigation on March 11, 1893, with the appointment of Special Commissioner James Blount whose duty was to “investigate and fully report to the President all the facts [he] can learn respecting the condition of affairs in the Hawaiian Islands, the causes of the revolution by which the Queen’s Government was overthrown, the sentiment of the people toward existing authority, and, in general, all that can fully enlighten the President touching the subjects of [his] mission.” After arriving in the Hawaiian Islands, he began his investigation on April 1, and by July 17, the fact-finding investigation was complete with a final report. Secretary of State Walter Gresham was receiving periodic reports from Special Commissioner Blount and was preparing a final report to the President.

On October 18, 1893, Secretary of State Gresham reported to the President, the “Provisional Government was established by the action of the American minister and the presence of the troops landed from the Boston, and its continued existence is due to the belief of the Hawaiians that if they made an effort to overthrow it, they would encounter the armed forces of the United States.” He further stated that the “Government of Hawaii surrendered its authority under a threat of war, until such time only as the Government of the United States, upon the facts being presented to it, should reinstate the constitutional sovereign, and the Provisional Government was created ‘to exist until terms of union with the United States of America have been negotiated and agreed upon (p. 462).’” Gresham then concluded, “Should not the great wrong done to a feeble but independent State by an abuse of the authority of the United States be undone by restoring the legitimate government? Anything short of that will not, I respectfully submit, satisfy the demands of justice (p. 463).”

Investigation Concludes United States Committed Acts of War against the Hawaiian Kingdom

One month later, on December 18, 1893, the President proclaimed by manifesto, in a message to the United States Congress, the circumstances for committing acts of war against the Hawaiian Kingdom that transformed a state of peace to a state of war on January 16, 1893. Black’s Law Dictionary defines a war manifesto as a “formal declaration, promulgated…by the executive authority of a state or nation, proclaiming its reasons and motives for…war.” And according to Professor Oppenheim in his seminal publication, International Law, vol. 2 (1906), a “war manifesto may…follow…the actual commencement of war through a hostile act of force (p. 104).”

Addressing the unauthorized landing of United States troops in the capital city of the Hawaiian Kingdom, President Cleveland stated, “on the 16th day of January, 1893, between four and five o’clock in the afternoon, a detachment of marines from the United States steamer Boston, with two pieces of artillery, landed at Honolulu. The men, upwards of 160 in all, were supplied with double cartridge belts filled with ammunition and with haversacks and canteens, and were accompanied by a hospital corps with stretchers and medical supplies (p. 451).”

President Cleveland ascertained that this “military demonstration upon the soil of Honolulu was of itself an act of war, unless made either with the consent of the Government of Hawaii or for the bona fide purpose of protecting the imperiled lives and property of citizens of the United States. But there is no pretense of any such consent on the part of the Government of the Queen, which at that time was undisputed and was both the de facto and the de jure government. In point of fact the existing government instead of requesting the presence of an armed force protested against it (p. 451).” He then stated, “a candid and thorough examination of the facts will force the conviction that the provisional government owes its existence to an armed invasion by the United States (p. 454).”

“War begins,” says Professor Wright in his article “Changes in the Conception of War,” American Journal of International Law, vol. 18 (1924), “when any state of the world manifests its intention to make war by some overt act, which may take the form of an act of war (p. 758).” According to Professor Hall in his book International Law (4th ed., 1895), the “date of the commencement of a war can be perfectly defined by the first act of hostility (p. 391).”

The President also determined that when “our Minister recognized the provisional government the only basis upon which it rested was the fact that the Committee of Safety had in the manner above stated declared it to exist. It was neither a government de facto nor de jure (p. 453).” He unequivocally referred to members of the so-called Provisional Government as insurgents, whereby he stated, and “if the Queen could have dealt with the insurgents alone her course would have been plain and the result unmistakable. But the United States had allied itself with her enemies, had recognized them as the true Government of Hawaii, and had put her and her adherents in the position of opposition against lawful authority. She knew that she could not withstand the power of the United States, but she believed that she might safely trust to its justice.” He then concluded that by “an act of war, committed with the participation of a diplomatic representative of the United States and without authority of Congress, the Government of a feeble but friendly and confiding people has been overthrown (p. 453).”

“Act of hostility unless it be done in the urgency of self-preservation or by way of reprisals,” according to Hall, “is in itself a full declaration of intent [to wage war] (p. 391).” According to Professor Wright in his article “When does War Exist,” American Journal of International Law, vol. 26(2) (1932), “the moment legal war begins…statutes of limitation cease to operate (p. 363).” He also states that war “in the legal sense means a period of time during which the extraordinary laws of war and neutrality have superseded the normal law of peace in the relations of states (Id.).”

Unbeknownst to the President at the time he delivered his message to the Congress, a settlement, through executive mediation, was reached between the Queen and United States Minister Albert Willis in Honolulu. The agreement of restoration, however, was never implemented. Nevertheless, President Cleveland’s manifesto was a political determination under international law of the existence of a state of war, of which there is no treaty of peace. More importantly, the President’s manifesto is paramount and serves as actual notice to all States of the conduct and course of action of the United States. These actions led to the unlawful overthrow of the government of an independent and sovereign State. When the United States commits acts of hostilities, the President, says Associate Justice Sutherland in his book Constitutional Power and World Affairs (1919), “possesses sole authority, and is charged with sole responsibility, and Congress is excluded from any direct interference (p. 75).”

According to Representative Marshall, before later became Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, in his speech in the House of Representatives in 1800, the “president is the sole organ of the nation in its external relations, and its sole representative with foreign nations. Of consequence, the demand of a foreign nation can only be made of him (Annals of Congress, vol. 10, p. 613).” Professor Wright in his book The Control of American Foreign Relations (1922), goes further and explains that foreign States “have accepted the President’s interpretation of the responsibilities [under international law] as the voice of the nation and the United States has acquiesced (p. 25).”

Despite the unprecedented prolonged nature of the illegal occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom by the United States, the Hawaiian State, as a subject of international law, is afforded all the protection that international law provides. “Belligerent occupation,” concludes Judge Crawford in his book The Creation of States in International Law (2nd ed., 2006), “does not affect the continuity of the State, even where there exists no government claiming to represent the occupied State (p. 34).” Without a treaty of peace, the laws of war and neutrality would continue to apply.

Addressing Americanization by the Hawaiian Council of Regency

The seventeenth of January will mark 126 years of the United States’ belligerent occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom. This outcome was initiated by “acts of war” committed by U.S. forces when the U.S. diplomat ordered an invasion on January 16, 1893, which led to the unlawful overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government on January 17th.[1] President Grover Cleveland, in his manifesto to the Congress on December 18, 1893, acknowledged that a “substantial wrong has thus been done which a due regard for our national character as well as the rights of the injured people requires we should endeavor to repair.”[2]

Instead of restoring the Hawaiian government under Queen Lili‘uokalani and repairing the “rights of the injured people,” the United States embarked on a history of deception, lies, the establishment of 118 military installations, and international crimes committed against civilians within Hawaiian territory. These injustices led to the restoration of the Hawaiian government, in situ, in 1995, in similar fashion to the formation of governments in exile during World War II under the doctrine of necessity, and to the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom arbitration, which sought to address the rights of one of those “injured people,” Lance Paul Larsen, a Hawaiian subject. Mr. Larsen was subjected to an unfair trial, unlawful confinement and pillaging by the State of Hawai‘i. These are violations of the 1907 Hague Convention, IV, and the 1949 Geneva Convention, IV, which are considered war crimes.

Lance Paul Larsen v. the Hawaiian Kingdom

The dispute centered on the allegation by Mr. Larsen that the Hawaiian government was liable for “allowing the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws over [him] within the territorial jurisdiction of the Hawaiian Kingdom.” What Mr. Larsen had to overcome was whether he could proceed to hold the Hawaiian government liable for the violation of his rights without the participation of the United States who was the entity that allegedly violated his rights.

On March 3, 2000, a meeting was held in Washington, D.C., with Mr. John Crook from the U.S. State Department, Dr. Sai as Agent for the Hawaiian government, and Ms. Ninia Parks, counsel for Mr. Larsen, where the United States was formally invited to join in the arbitration. A few weeks later, the United States notified the Permanent Court of Arbitration (“PCA”) that it will not join in the proceedings but they asked permission from the Hawaiian government and Mr. Larsen if it could have access to all pleadings and records of the case. Permission was granted. For Mr. Larsen, this gave rise to the indispensable third-party rule and whether or not he could proceed against the Hawaiian government without the participation of the United States. Unlike national courts, international courts do not have subpoena powers.

The Larsen Tribunal eventually ruled that the United States was an indispensable third-party, and without its participation in the proceedings, the Tribunal could not determine what rights of Mr. Larsen were violated by the United States in order to hold the Hawaiian government accountable for the violation of those rights. The Tribunal, however, did state in its decision that the parties could pursue fact-finding through a commission of inquiry under the jurisdiction of the PCA whenever it may enter into an agreement to do so. Fact-finding is not affected by the indispensable third-party rule, which operates in similar fashion to a United States grand jury.

After the last day of the Larsen hearings were held at the PCA on December 11, 2000, the Council, was called to an urgent meeting by Dr. Jacques Bihozagara, Ambassador for the Republic of Rwanda assigned to Belgium. Ambassador Bihozagara had been attending a hearing before the International Court of Justice on December 8, 2000, (Democratic Republic of the Congo v. Belgium), where he became aware of the Hawaiian arbitration case at the PCA.

The following day, the Council, which included Dr. Sai, as Agent, and two Deputy Agents, Peter Umialiloa Sai, acting Minister of Foreign Affairs, and Mrs. Kau‘i P. Sai-Dudoit, formerly known as Kau‘i P. Goodhue, acting Minister of Finance, met with Ambassador Bihozagara in Brussels, Belgium.[3] In that meeting, Ambassador Bihozagara explained, that since he accessed the pleadings and records of the Larsen case on December 8, he had been in communication with his government. This prompted the meeting where he conveyed to Dr. Sai, as Chairman of the Council and agent in the Larsen case, that his government was prepared to bring to the attention of the United Nations General Assembly the prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom by the United States.

After careful deliberation, the Council decided that it could not, in good conscience, accept this offer. The Council felt the timing was premature because Hawai‘i’s population remained ignorant of Hawai‘i’s profound legal position due to institutionalized denationalization—Americanization by the United States. Therefore, on behalf of the Council, Dr. Sai graciously thanked Ambassador Bihozagara for his government’s offer but stated that the Council first needed to address over a century of this denationalization. After an exchange of salutations, the meeting came to an end, and the Council returned that afternoon to The Hague.

Exposure of the Continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom through the medium of Education

The decision by the Council to forego Ambassador Bihozagara’s invitation was made in line with section 495—Remedies of Injured Belligerent, United States Army FM-27-10, which states, “In the event of violation of the law of war, the injured party may legally resort to remedial action of the following types: a. Publication of the facts, with a view to influencing public opinion against the offending belligerent.”[4] Publication of the facts was the means the Council would focus its attention on to expose the prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the circumstances of the Larsen case.

“When a well packaged web of lies has been sold to the masses over generations, the truth will seem utterly preposterous, and its speaker, a raving lunatic.” -Donald James Wheal

The belligerent occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom by the United States rests squarely within the regime of the law of occupation in international humanitarian law. The application of the regime of occupation law “does not depend on a decision taken by an international authority”,[5] and “the existence of an armed conflict is an objective test and not a national ‘decision.’”[6] According to Article 42 of the 1907 Hague Convention, IV, a State’s territory is considered occupied when it is “actually placed under the authority of the hostile army.”

Article 42 has three requisite elements: (1) the presence of a foreign State’s forces; (2) the exercise of authority over the occupied territories by the foreign State or its proxy; and (3) the non-consent by the occupied State. U.S. President Grover Cleveland’s aforementioned manifesto to the Congress, which is Annexure 1 in the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom Award, and the continued U.S. presence today without a treaty of peace firmly meets all three elements of Article 42. Hawai‘i’s people, however, have become denationalized and the history of the Hawaiian Kingdom has been, for all intents and purposes, obliterated since the United States’ takeover.

The Council needed to explain to Hawai‘i’s people that before the Permanent Court of Arbitration (“PCA”) could facilitate the formation of the Larsen tribunal the PCA had to ensure that it possessed “institutional jurisdiction.”[7] This jurisdiction required that the Hawaiian Kingdom be an existing “State.” This finding authorized the Hawaiian Kingdom’s access to the PCA pursuant to Article 47 of the 1907 Hague Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes, as a non-Contracting Power to the convention.

The PCA accepted the Larsen case as a dispute between a “State” and “private entity” and, in its annual reports from 2001 to 2011, acknowledged the Hawaiian Kingdom as a non-Contracting Power under Article 47 of the 1907 Hague Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes. For Hawai‘i’s people, this acknowledgement is significant on two levels, first, the Hawaiian Kingdom had to exist as a State under international law, otherwise the PCA would not have accepted the dispute to be settled through international arbitration, and, second, the PCA explicitly recognized the Hawaiian Kingdom as a non-Contracting Power (State) to the 1907 Hague Convention, I. A non-Contracting Power is a State that is not a signatory to the Convention.

To accomplish this educational goal, it was decided by the Council that Dr. Sai enter the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa political science department and secure an M.A. degree specializing in international relations, and then a Ph.D. with focus on the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent and sovereign State that has been under a prolonged occupation. From the University of Hawai‘i political science department, Professor Neal Milner, Professor John Wilson, and Professor Katherina Hyer; from the University of Hawai‘i Hawaiian Studies department, Professor Jon Osorio; from the University of Hawai‘i William S. Richardson School of Law—Professor Aviam Soifer; and from the University of London, SOAS, Professor Matthew Craven, served as members of his doctoral committee.

The Council’s objective was to engage over a century of denationalization through the medium of academic research and publications, both peer review and law review. As a result, awareness of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s political status has grown exponentially with multiple master’s theses, doctoral dissertations, and publications being written on the subject. What the world knew, before the Larsen case was held from 1999-2001, was drastically transformed to now. This transformation was the result of academic research in spite of the continued American occupation. The “injured people” began to ask the right questions.

“If they can get you asking the wrong questions, they don’t have to worry about answers.” -Thomas Pynchon

This scholarship prompted a well-known historian in Hawai‘i, Tom Coffman, to change the subtitle of his book in 2009, which Duke University republished in 2016, from The Story of America’s Annexation of the Nation of Hawai‘i to The History of the American Occupation of Hawai‘i. Coffman explained:

I am compelled to add that the continued relevance of this book reflects a far-reaching political, moral and intellectual failure of the United States to recognize and deal with its takeover of Hawai‘i. In the book’s subtitle, the word Annexation has been replaced by the word Occupation, referring to America’s occupation of Hawai‘i. Where annexation connotes legality by mutual agreement, the act was not mutual and therefore not legal. Since by definition of international law there was no annexation, we are left with the word occupation.

In making this change, I have embraced the logical conclusion of my research into the events of 1893 to 1898 in Honolulu and Washington, D.C. I am prompted to take this step by a growing body of historical work by a new generation of Native Hawaiian scholars. Dr. Keanu Sai writes, ‘The challenge for…the fields of political science, history, and law is to distinguish between the rule of law and the politics of power.’ In the history of Hawai‘i, the might of the United States does not make it right.[8]

In 2016, Japan’s Seijo University’s Center for Glocal Studies published an article by Dennis Riches titled This is not America: The Acting Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom Goes Global with Legal Challenges to End Occupation. At the center of this article was the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom, the Council of Regency, and the commission war crimes. Riches, who is Canadian, wrote:

[The history of the Baltic States] is a close analog of Hawai‘i because the occupation by a superpower lasted over several decades through much of the same period of history. The restoration of the Baltic States illustrates that one cannot say too much time has passed, too much has changed, or a nation is gone forever once a stronger nation annexes it. The passage of time doesn’t erase sovereignty, but it does extend the time which the occupying power has to neglect its duties and commit a growing list of war crimes.

Additionally, school teachers, throughout the Hawaiian Islands, have also been made aware of the American occupation through course work at the University of Hawai‘i and they are teaching this material in the middle schools and the high schools. This exposure led the Hawai‘i State Teachers Association (“HSTA”), which represents public school teachers throughout Hawai‘i, to introduce a resolution—New Business Item 37, on July 4, 2017, at the annual assembly of the National Education Association (“NEA”) in Boston, Massachusetts. The NEA represents 3.2 million public school teachers, administrators, and faculty and administrators of universities throughout the United States. The resolution stated:

The NEA will publish an article that documents the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Monarchy in 1893, the prolonged illegal occupation of the United States in the Hawaiian Kingdom, and the harmful effects that this occupation has had on the Hawaiian people and resources of the land.

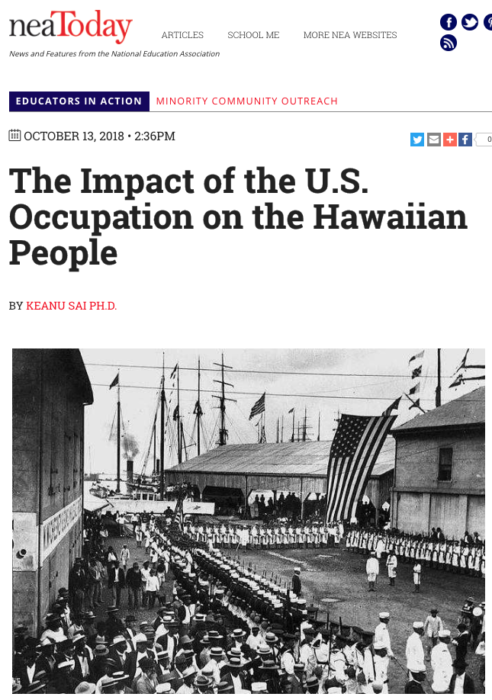

When the HSTA delegates in attendance returned to Hawai‘i, they asked Dr. Sai to write three articles for the NEA to publish: first, The Illegal Overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom Government (April 2, 2018); second, The U.S. Occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom (October 1, 2018); and, third, The Impact of the U.S. Occupation on the Hawaiian People (October 13, 2018). Awareness of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s situation has reached countless classrooms across the United States. These publications by the NEA was the Council’s crowning jewel which stemmed from the Council’s decision to address denationalization after returning home from the PCA in 2000.

Russian Government Admits Hawai‘i was Illegally Annexed

This exposure also prompted the Russian government, on October 4, 2018, to admit that Hawai‘i was illegally annexed by the United States. This acknowledgement occurred at a seminar entitled “Russian America: Hawaiian Pages 200 Years After” held at the PIR-CENTER, Institute of Contemporary International Studies, Diplomatic Academy of the Russian Foreign Ministry, in Moscow. The topic of the seminar was the restoration of Fort Elizabeth, a Russian fort built on the island of Kaua‘i in 1817.

Leading the seminar was Dr. Vladimir Orlov, director of the PIR-CENTER. Notable participants included Deputy Foreign Minister Sergej Ryabkov, Head of the Department of European Co-operation and specialist on nuclear and other disarmament negotiations, and Russian Ambassador to the United States, Anatoly Antonov. In his concluding remarks Dr. Orlov, who incidentally referred to the U.S. military installations at Barking Sands, mentioned as an aside and in a relatively low voice: “The annexation of Hawai‘i by the US was of course illegal and everyone knows it.”

United Nations Independent Expert on Hawai‘i’s Occupation

This educational exposure also prompted United Nations Independent Expert, Dr. Alfred M. deZayas, to send a communication, dated February 25, 2018, to members of the State of Hawai‘i Judiciary stating that the Hawaiian Kingdom is an occupied State and that the 1907 Hague Convention, IV, and the 1949 Geneva Convention, IV, must be complied with. In that communication, Dr. deZayas stated:

I have come to understand that the lawful political status of the Hawaiian Islands is that of a sovereign nation-state in continuity; but a nation-state that is under a strange form of occupation by the United States resulting from an illegal military occupation and a fraudulent annexation. As such, international laws (the Hague and Geneva Conventions) require that governance and legal matters within the occupied territory of the Hawaiian Islands must be administered by the application of the laws of the occupied state (in this case, the Hawaiian Kingdom), not the domestic laws of the occupier (the United States).

This UN Independent Expert clearly stated the application of “the Hague and Geneva Conventions” requires the administration of Hawaiian Kingdom law, not United States law, in Hawaiian territory. This issue was at the center of the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom arbitration case. His characterization of a “strange occupation” is not a diminishment of the law of occupation, but rather a consequence of not complying with the law of occupation. This noncompliance has created the façade of an incorporated territory of the United States called the State of Hawai‘i. The State of Hawai‘i is a de facto proxy for the United States and maintains effective control over Hawaiian territory. The War Report 2017 refers to such entities as an armed non-state actor (ANSA) “operating in another state when that support is so significant that the foreign state is deemed to have ‘overall control’ over the actions of the ANSA.”[9]

Between the years of 1893 to 1898, the Hawaiian Kingdom was occupied by an American proxy of insurgents. There is no treaty of peace between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States except for the unilateral annexation of the Hawaiian Islands by a joint resolution of Congress. Whether by proxy or not, the United States is the occupying State and “as the right of an occupant in occupied territory is merely a right of administration, he may [not] annex it, while the war continues.”[10] The ICRC Commentary on Article 47 also emphasize, “It will be well to note that the reference to annexation in this Article cannot be considered as implying recognition of this manner of acquiring sovereignty.”[11]

The “Occupying Power cannot…annex the occupied territory, even if it occupies the whole of the territory concerned. A decision on that point can only be reached in a peace treaty. This is a universally-recognized rule and is endorsed by jurists and confirmed by numerous rulings of international and national courts.”[12] Therefore, according to the ICRC, “an Occupying Power continues to be bound to apply the Convention as a whole even when, in disregard of the rules of international law, it claims to have annexed all or part of an occupied territory.”[13] In other words, since there is no treaty of peace between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States, there was no annexation.

To understand what the UN Independent Expert called a “fraudulent annexation,” attention is drawn to the floor of the Senate on July 4, 1898, where U.S. Senator William Allen of Nebraska stated:

“The Constitution and the statutes are territorial in their operation; that is, they can not have any binding force or operation beyond the territorial limits of the government in which they are promulgated. In other words, the Constitution and statutes can not reach across the territorial boundaries of the United States into the territorial domain of another government and affect that government or persons or property therein.”[14]

Two years later, on February 28, 1900, during a debate on senate bill no. 222 that proposed the establishment of a U.S. government to be called the Territory of Hawai‘i, Senator Allen reiterated, “I utterly repudiate the power of Congress to annex the Hawaiian Islands by a joint resolution such as passed the Senate. It is ipso facto null and void.”[15] In response, Senator John Spooner of Wisconsin, a constitutional lawyer, dismissively remarked, “that is a political question, not subject to review by the courts.”[16] Senator Spooner explained, “The Hawaiian Islands were annexed to the United States by a joint resolution passed by Congress. I reassert…that that was a political question and it will never be reviewed by the Supreme Court or any other judicial tribunal.”[17]

Senator Spooner never argued that congressional laws have authority beyond United States territory. Instead, he said this issue would never see the light of day because United States courts would not review it due to the political question doctrine. What Senator Spooner meant was no matter how illegal the annexation was, the American courts will have to accept it because Congress did it. For an explanation of the evolution of the political question doctrine regarding Hawai‘i go to this link. This exchange between the two Senators is troubling, but it acknowledges the limitation of congressional laws and the political means by which to conceal an internationally wrongful act. The Territory of Hawai‘i is the predecessor of the State of Hawai‘i.

It would take another ninety years before the U.S. Department of Justice addressed this issue. In a 1988 legal opinion, the Office of Legal Counsel examined the purported annexation of the Hawaiian Islands by a congressional joint resolution. Douglas Kmiec, Acting Assistant Attorney General, authored this opinion for Abraham D. Sofaer, legal advisor to the U.S. Department of State. After covering the limitation of congressional authority, which, in effect, confirmed the statements made by Senator Allen, Assistant Attorney General Kmiec concluded:

Notwithstanding these constitutional objections, Congress approved the joint resolution and President McKinley signed the measure in 1898. Nevertheless, whether this action demonstrates the constitutional power of Congress to acquire territory is certainly questionable. … It is therefore unclear which constitutional power Congress exercised when it acquired Hawaii by joint resolution. Accordingly, it is doubtful that the acquisition of Hawaii can serve as an appropriate precedent for a congressional assertion of sovereignty over an extended territorial sea.[18]

War Crimes—Violations of the Hague and Geneva Conventions

All this education and exposure has motivated an elected official for the State of Hawai‘i, while still in office, to take steps to conform to the 1907 Hague Convention, IV, and the 1949 Geneva Convention, IV. Her story was published by the British news outlet The Guardian, titled Hawai‘i politician stops voting, claiming islands are ‘occupied sovereign country.’ Other public officials of the State of Hawai‘i have also become aware of the American occupation and are taking steps to conform with international humanitarian law. They have reached out to Dr. Sai for consultation.

Moreover, on October 11, 2018, the Federal Bureau of Investigation was sent a letter, from Jennifer Ruggles, the aforementioned State of Hawai‘i public official, reporting war crimes committed by the Queen’s Hospital, in violation of 18 U.S.C. §2441 and §1091, and war crimes committed by thirty-two Circuit Judges of the State of Hawai‘i, in violation of 18 U.S.C. §2441.[19] Thereafter, Ms. Ruggles reported additional war crimes of pillaging committed by State of Hawai‘i tax collectors, in violation of §2441,[20] the war crime of unlawful appropriation of property by the President of the United States and the Internal Revenue Service, in violation of §2441,[21] and the war crime of destruction of property by the State of Hawai‘i on the summit of Mauna Kea, in violation of §2441.[22]

Naboth’s Vineyard

Within nearly two decades the Council has effectively changed the discourse of Hawai‘i politics and history from the façade of American colonization and the formation of the State of Hawai‘i to the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a sovereign and independent State that has and continues to be under an illegal and prolonged occupation by the United States.

As we are entering over a century of non-compliance with the law of occupation and the commission of war crimes, accountability for these war crimes is just over the horizon. In her last chapter titled “Hawaiian Autonomy” of her 1898 autobiography, Hawai‘i’s Story by Hawai‘i’s Queen, Queen Lili‘uokalani warned:

Oh, honest Americans, as Christians, hear me for my down trodden people! Their form of government is as dear to them as yours is precious to you. Quite as warmly as you love your country, so they love theirs. With all your goodly possessions, covering a territory so immense that there yet remain parts unexplored, possessing islands that, although near at hand, had to be neutral ground in time of war, do not covet the little vineyard of Naboth’s so far from your shores, lest the punishment of Ahab fall upon you, if not in your day in that of your children, for “for be not deceived, God is not mocked.”

[1] Award (Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom), Annexure 1, President Cleveland’s message to the Senate and House of Representatives dated 18 December 1893, 119 ILR (2001), 566, 608.

[2] Id.

[3] David Keanu Sai, A Slippery Path towards Hawaiian Indigeneity, 10 J. L. & Soc. Challenges 69, 130-131 (2008).

[4] “United States Basic Field Manual F.M. 27-10 (Rules of Land Warfare), though not a source of law like a statute, prerogative order or decision of a court, is a very authoritative publication.” Trial of Sergeant-Major Shigeru Ohashi and Six Others, 5 Law Reports of Trials of Law Criminals (United Nations War Crime Commission) 27 (1949).

[5] C. Ryngaert and R. Fransen, “EU extraterritorial obligations with respect to trade with occupied territories: Reflections after the case of Front Polisario before EU courts,” [2018] 2(1): 7. Europe and the World: A law review [20], p. 8. (online at https://www.scienceopen.com/document_file/e5cc1ac6-41ee-40de-bbe9-25c9df97ab1e/ScienceOpen/EWLR-2-7.pdf).

[6] Stuart Casey-Maslen (ed.), The War Report 2012 ix (2013).

[7] United Nations, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: Dispute Settlement (United Nations New York and Geneva, 2003), at 15.

[8] Tom Coffman, Nation Within: The History of the American Occupation of Hawai‘i xvi (2016).

[9] The War Report 2017, 22.

[10] Oppenheim, International Law, vol. II, 6th ed., 237 (1921).

[11] International Committee of Red Cross, Commentary: IV Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War 276 (1958).

[12] Id., 275.

[13] Id., 276.

[14] 31 Cong. Rec. 6635 (1898).

[15] 33 Cong. Rec. 2391 (1900).

[16] Id.

[17] Id.

[18] 12 Opinions of the Office of Legal Counsel 238, 252 (1988) (online at https://hawaiiankingdom.org/pdf/1988_Opinion_OLC.pdf).

[19] Letter from Jennifer Ruggles, Hawai‘i County Council member, State of Hawai‘i, to Sean Kaul, FBI Special Agent in Charge (11 Oct. 2018) (online at https://jenruggles.com/wp-content/uploads/Reporting_to_FBI_10.11.18.pdf).

[20] Letter from Jennifer Ruggles, Hawai‘i County Council member, State of Hawai‘i, to State of Hawai‘i officials regarding unlawful collection of taxes (15 Nov. 2018) (online at https://jenruggles.com/wp-content/uploads/Ltr-to-State-of-HI-re-Taxes.pdf).

[21] Letter from Jennifer Ruggles, Hawai‘i County Council member, State of Hawai‘i, to U.S. President Trump regarding unlawful appropriation of property (28 Nov. 2018) (online at https://jenruggles.com/wp-content/uploads/Ltr_to_President_Trump.pdf).

[22] Letter from Jennifer Ruggles, Hawai‘i County Council member, State of Hawai‘i, to State of Hawai‘i Governor Ige and Supreme Court Justices regarding unlawful destruction of property on the summit of Mauna Kea (3 Dec. 2018) (online at https://jenruggles.com/wp-content/uploads/Ltr-to-Gov.-and-Sup.-Ct.pdf).

A Reenactment of a Historic Meeting in Hilo in 1897 Protesting Annexation to the United States

National Holiday – Independence Day (November 28)

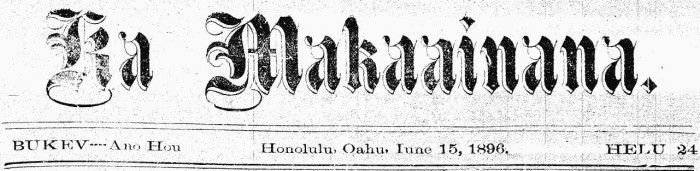

November 28th is the most important national holiday in the Hawaiian Kingdom. It is the day Great Britain and France formally recognized the Hawaiian Islands as an “independent state” in 1843, and has since been celebrated as “Independence Day,” which in the Hawaiian language is “La Ku‘oko‘a.” Here follows the story of this momentous event from the Hawaiian Kingdom Board of Education history textbook titled “A Brief History of the Hawaiian People” published in 1891.

**************************************

The First Embassy to Foreign Powers—In February, 1842, Sir George Simpson and Dr. McLaughlin, governors in the service of the Hudson Bay Company, arrived at Honolulu  on business, and became interested in the native people and their government. After a candid examination of the controversies existing between their own countrymen and the Hawaiian Government, they became convinced that the latter had been unjustly accused. Sir George offered to loan the government ten thousand pounds in cash, and advised the king to send commissioners to the United States and Europe with full power to negotiate new treaties, and to obtain a

on business, and became interested in the native people and their government. After a candid examination of the controversies existing between their own countrymen and the Hawaiian Government, they became convinced that the latter had been unjustly accused. Sir George offered to loan the government ten thousand pounds in cash, and advised the king to send commissioners to the United States and Europe with full power to negotiate new treaties, and to obtain a guarantee of the independence of the kingdom.

guarantee of the independence of the kingdom.

Accordingly Sir George Simpson, Haalilio, the king’s secretary, and Mr. Richards were appointed joint ministers-plenipotentiary to the three powers on the 8th of April, 1842.

Mr. Richards also received full power of attorney for the king. Sir George left for Alaska, whence he traveled through Siberia, arriving in England in November. Messrs. Richards and Haalilio sailed July 8th, 1842, in a chartered schooner for Mazatlan, on their way to the United States*

Mr. Richards also received full power of attorney for the king. Sir George left for Alaska, whence he traveled through Siberia, arriving in England in November. Messrs. Richards and Haalilio sailed July 8th, 1842, in a chartered schooner for Mazatlan, on their way to the United States*

*Their business was kept a profound secret at the time.

Proceedings of the British Consul—As soon as these facts became known, Mr. Charlton followed the embassy in order to defeat its object. He left suddenly on September 26th, 1842, for London via Mexico, sending back a threatening letter to the king, in which he informed him that he had appointed Mr. Alexander Simpson as acting-consul of Great Britain. As this individual, who was a relative of Sir George, was an avowed advocate of the annexation of the islands to Great Britain, and had insulted and threatened the governor of Oahu, the king declined to recognize him as British consul. Meanwhile Mr. Charlton laid his grievances before Lord George Paulet commanding the British frigate “Carysfort,” at Mazatlan, Mexico. Mr. Simpson also sent dispatches to the coast in November, representing that the property and persons of his countrymen were in danger, which introduced Rear-Admiral Thomas to order the “Carysfort” to Honolulu to inquire into the matter.

Recognition by the United States—Messres. Richards and Haalilio arrived in Washington early in December, and had several interviews with Daniel Webster, the Secretary of State, from whom they received an official letter December 19th, 1842, which recognized the independence of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and declared, “as the sense of the government of the United States, that the government of the Sandwich Islands ought to be respected; that no power ought to take possession of the islands, either as a conquest or for the purpose of the colonization; and that no power ought to seek for any undue control over the existing government, or any exclusive privileges or preferences in matters of commerce.” *

Secretary of State, from whom they received an official letter December 19th, 1842, which recognized the independence of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and declared, “as the sense of the government of the United States, that the government of the Sandwich Islands ought to be respected; that no power ought to take possession of the islands, either as a conquest or for the purpose of the colonization; and that no power ought to seek for any undue control over the existing government, or any exclusive privileges or preferences in matters of commerce.” *

*The same sentiments were expressed in President Tyler’s message to Congress of December 30th, and in the Report of the Committee on Foreign Relations, written by John Quincy Adams.

Success of the Embassy in Europe—The king’s envoys proceeded to London, where they had been preceded by the Sir George Simpson, and had an interview with the Earl of Aberdeen, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, on the 22d of February, 1843.

they had been preceded by the Sir George Simpson, and had an interview with the Earl of Aberdeen, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, on the 22d of February, 1843.

Lord Aberdeen at first declined to receive them as ministers from an independent state, or to negotiate a treaty, alleging that the king did not govern, but that he was “exclusively under the influence of Americans to the detriment of British interests,” and would not admit that the government of the United States had yet fully recognized the independence of the islands.

Sir George and Mr. Richards did not, however, lose heart, but went on to Brussels March 8th, by a previous arrangement made with Mr. Brinsmade. While there, they had an interview with Leopold I., king of the Belgians, who received them with great courtesy, and promised to use his influence to obtain the recognition of Hawaiian independence. This influence was great, both from his eminent personal qualities and from his close relationship to the royal families of England and France.

Encouraged by this pledge, the envoys proceeded to Paris, where, on the 17th, M. Guizot, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, received them in the kindest manner, and at once engaged, in behalf of France, to recognize the independence of the islands. He made the same statement to Lord Cowley, the British ambassador, on the 19th, and thus cleared the way for the embassy in England.

They immediately returned to London, where Sir George had a long interview with Lord Aberdeen on the 25th, in which he explained the actual state of affairs at the islands, and received an assurance that Mr. Charlton would be removed. On the 1st of April, 1843, the Earl of Aberdeen formally replied to the king’s commissioners, declaring that “Her Majesty’s Government are willing and have determined to recognize the independence of the Sandwich Islands under their present sovereign,” but insisting on the perfect equality of all foreigners in the islands before the law, and adding that grave complaints had been received from British subjects of undue rigor exercised toward them, and improper partiality toward others in the administration of justice. Sir George Simpson left for Canada April 3d, 1843.

Recognition of the Independence of the Islands—Lord Aberdeen, on the 13th of June, assured the Hawaiian envoys that “Her Majesty’s government had no intention to retain possession of the Sandwich Islands,” and a similar declaration was made to the governments of France and the United States.

At length, on the 28th of November, 1843, the two governments of France and England united in a joint declaration to the effect that “Her Majesty, the queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and His Majesty, the king of the French, taking into consideration the existence in the Sandwich Islands of a government capable of providing for the regularity of its relations with foreign nations have thought it right to engage reciprocally to consider the Sandwich Islands as an independent state, and never to take possession, either directly or under the title of a protectorate, or under any other form, of any part of the territory of which they are composed…”

This was the final act by which the Hawaiian Kingdom was admitted within the pale of civilized nations. Finding that nothing more could be accomplished for the present in Paris, Messrs. Richards and Haalilio returned to the United States in the spring of 1844. On the 6th of July they received a dispatch from Mr. J.C. Calhoun, the Secretary of State, informing them that the President regarded the statement of Mr. Webster and the appointment of a commissioner “as a full recognition on the part of the United States of the independence of the Hawaiian Government.”

This was the final act by which the Hawaiian Kingdom was admitted within the pale of civilized nations. Finding that nothing more could be accomplished for the present in Paris, Messrs. Richards and Haalilio returned to the United States in the spring of 1844. On the 6th of July they received a dispatch from Mr. J.C. Calhoun, the Secretary of State, informing them that the President regarded the statement of Mr. Webster and the appointment of a commissioner “as a full recognition on the part of the United States of the independence of the Hawaiian Government.”

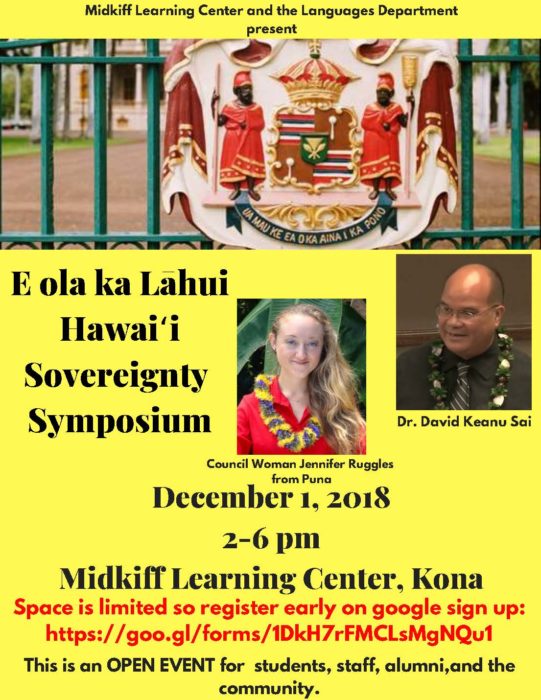

Kamehameha Schools Midkiff Learning Center: Hawai‘i Sovereignty Symposium

NEA Teachers Union Published Third and Final Article on the American Occupation of Hawai‘i

As part of a three part series the National Education Association (NEA) has published the third and final article on the American occupation of Hawai‘i. The NEA is the largest labor union in the United States comprised of public school teachers, administrators, and faculty and administrators of universities. This third and final article is titled “The Impact of the U.S. Occupation on the Hawaiian People.”

The NEA’s article stems from a resolution that was passed by its delegates who met at their annual convention in 2017 in Boston, Massachusetts.

The resolution was introduced by the delegates of the Hawai‘i State Teachers Association, which is an affiliate labor union of the NEA, and it passed on July 4, 2017. The resolution was referred to as New Business Item 37, which stated:

“The NEA will publish an article that documents the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Monarchy in 1893, the prolonged occupation of the United States in the Hawaiian Kingdom and the harmful effects that this occupation has had on the Hawaiian people and resources of the land.”

#ProtectedPersonsHawaii

#WarCrimesHawaii

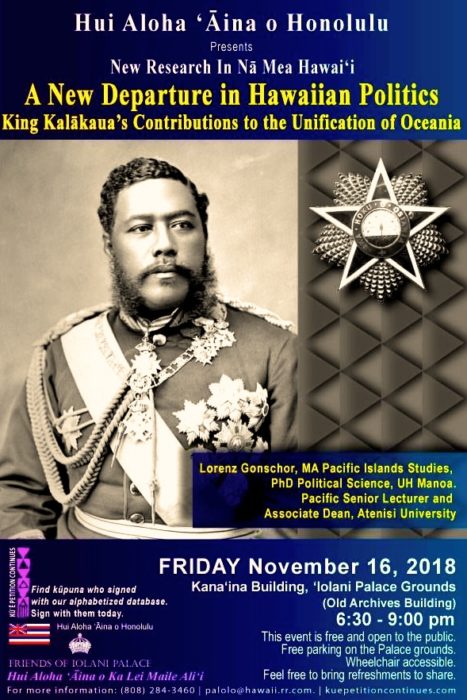

King Kalakaua’s Contribution to the Unification of Oceania

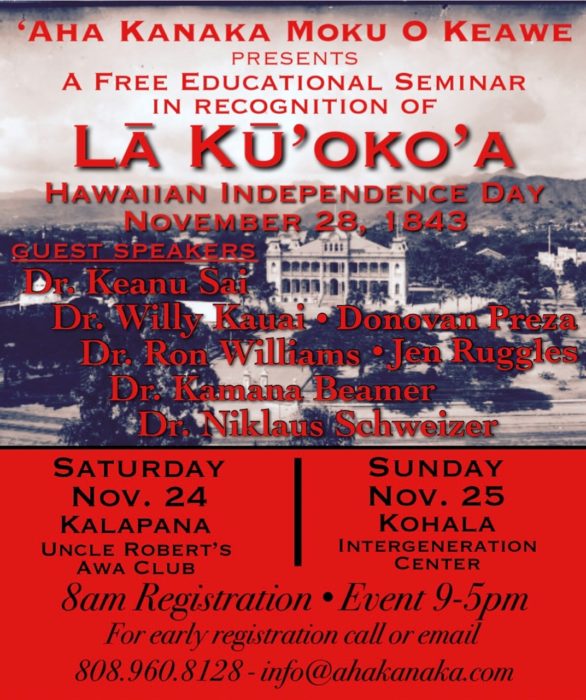

La Ku‘oko‘a (Independence Day) on Hawai‘i Island

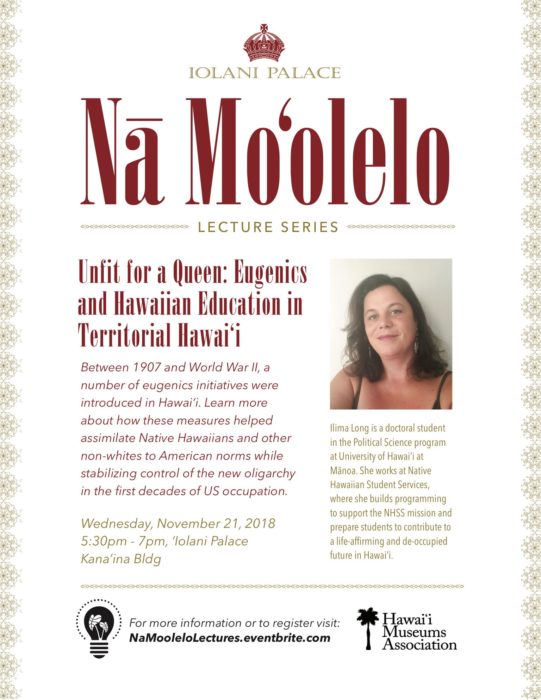

Unfit for a Queen: Eugenics and Hawaiian Education in Territorial Hawai‘i

NEA Teachers Union Published Second Article on the American Occupation of Hawai‘i

As part of a three part series the National Education Association (NEA) has published a second article on the American occupation of Hawai‘i. The NEA is the largest labor union in the United States comprised of public school teachers, administrators, and faculty and administrators of universities. This second of three articles is titled “The U.S. Occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom.”

The NEA’s article stems from a resolution that was passed by its delegates who met at their annual convention in 2017 in Boston, Massachusetts.

The NEA’s article stems from a resolution that was passed by its delegates who met at their annual convention in 2017 in Boston, Massachusetts.

The resolution was introduced by the delegates of the Hawai‘i State Teachers Association, which is an affiliate labor union of the NEA, and it passed on July 4, 2017. The resolution was referred to as New Business Item 37, which stated:

“The NEA will publish an article that documents the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Monarchy in 1893, the prolonged occupation of the United States in the Hawaiian Kingdom and the harmful effects that this occupation has had on the Hawaiian people and resources of the land.”

#ProtectedPersonsHawaii

#WarCrimesHawaii

The Three Estates of the Hawaiian Kingdom

There are some today who mistakenly believe that if they can show a family genealogy that traces back to a Hawaiian ali‘i (nobility) they can lay claim to the throne. If this were true than anyone can lay claim. But it is not true because the Hawaiian Kingdom is a constitutional monarchy that provides rules and protocol.

The first rule is that under Hawaiian law titles of nobility are not inheritable. However, in Europe titles of nobility are inheritable, which traces back to the Middle Ages. This is a feudal rule that developed when the nobility were able to inherit their lands and consequently their titles were also inheritable within the family. The Hawaiian Kingdom did not rise from the Middle Ages. It is Polynesian. According to Article 35 of the 1864 Hawaiian Constitution “All Titles of Honor, Orders, and other distinctions, emanate from the King.”

Three Estates of the Hawaiian Kingdom

The government of the Hawaiian Kingdom is a constitutional and limited monarchy comprised of three Estates: the Monarch, Nobles and the People. An Estate is defined as a “political class.” All three political classes work in concert and provides for the legal basis of the government and its authority. Article 45 of the 1864 Hawaiian constitution, provides: “The Legislative power of the Three Estates of this Kingdom is vested in the King, and the Legislative Assembly; which Assembly shall consist of the Nobles appointed by the King, and of the Representatives of the People, sitting together.”

This provision is further elaborated under §768, Hawaiian Civil Code (Compiled Laws, 1884), “The Legislative Department of this Kingdom is composed of the King, the House of Nobles, and the House of Representatives, each of whom has a negative on the other, and in whom is vested full power to make all manner of wholesome laws, as they shall judge for the welfare of the nation, and for the necessary support and defense of good government, provided the same is not repugnant or contrary to the Constitution.” As each Estate has a negative on each other, no law can be passed without all three Estates agreeing.

According to Hawaiian law “No person shall ever sit upon the Throne, who has been convicted of any infamous crime, or who is insane, or an idiot (Article 25, 1864 Constitution),” which, by extension, extends to the Nobles whereby “The King appoints the members of the House of Nobles, who hold their seats during life, unless in case of resignation, subject, however, to punishment for disorderly behavior. The number of members of the House of Nobles shall not exceed thirty (§771, Compiled Laws).”

Representatives of the People shall be Hawaiian subjects or denizens “who shall have arrived at the full age of twenty-five years, who shall know how to read and write; who shall understand accounts, and who shall have resided in the Kingdom for at least one year immediately preceding his election; provided always, that no person who is insane, or an idiot, or who shall at any time have been convicted of theft, bribery, perjury, forgery, embezzlement, polygamy, or other high crime or misdemeanor, shall ever hold seat as Representative of the people (§778, Compiled Laws).”

The number of the Representatives of the people in the Legislature shall be twenty-eight: eight for the Island of Hawai‘i (one for the district of North Kona, one for the district of South Kona, One for the district of Ka‘u, one for the district Puna, two for the district of Hilo, one for the district Hamakua, one for the district of Kohala); seven for the Island of Maui (two for the districts of Lahaina, Olowalu, Ukumehame, and Kaho‘olawe, one for the districts of Kahakuloa and Ka‘anapali, one for the districts of Waihe‘e and Honuaula, one for the districts of Kahikinui and Ko‘olau, one for the districts of Hamakualoa and Kula); two for the Islands of Molokai and Lanai; eight for the Island of O‘ahu (four for the districts of Honolulu that extends from Maunalua to Moanalua, one for the districts of Ewa and Waianae, one for the district of Waialua, one for the district of Ko‘olauloa, and one for the district of Ko‘olaupoko); and three for the island of Kaua‘i (one for the districts of Waimea, Nualolo, Hanapepe and the Island of Ni‘ihau, one for the districts of Puna, Wahiawa and Wailua, and one for the districts of Hanalei, Kapa‘a and ‘Awa‘awapuhi) (§780, Compiled Laws).

Electors of the Representatives shall be Hawaiian subjects or denizens “who shall have paid his taxes, who shall have attained the age of twenty years, and shall have been domiciled in the Kingdom for one year immediately preceding the election, and shall know how to read and write, if born since the year 1840, and shall have caused his name to be entered on the list of voters of his district…shall be entitled to one vote for Representative or Representatives of that district; provided, however, that no insane or idiotic person, or any person who shall have been convicted of any infamous crime within this Kingdom unless he shall have been pardoned by the King, and by the terms, and by the terms of such pardon have been restored to all the rights of a subject, shall be allowed to vote (p. 222, Compiled Laws).”

The Estate of the Crown

The first constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom was promulgated in 1840 by King Kamehameha III, which was superseded by the 1852 Constitution. Article 25 of the 1852 Constitution provided: “The crown is hereby permanently confirmed to His Majesty Kamehameha III. during his life, and to his successor. The successor shall be the person whom the King and the House of Nobles shall appoint and publicly

The first constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom was promulgated in 1840 by King Kamehameha III, which was superseded by the 1852 Constitution. Article 25 of the 1852 Constitution provided: “The crown is hereby permanently confirmed to His Majesty Kamehameha III. during his life, and to his successor. The successor shall be the person whom the King and the House of Nobles shall appoint and publicly  proclaim as such, during the King’s life; but should there be no such appointment and proclamation, then the successor shall be chosen by the House of Nobles and the House of Representatives in joint ballot.” Kamehameha III proclaimed his adopted son, Alexander Liholiho, to be his heir apparent after receiving confirmation from the Nobles in 1853. Alexander ascended to the Throne upon the death of King Kamehameha III on December 15, 1854.

proclaim as such, during the King’s life; but should there be no such appointment and proclamation, then the successor shall be chosen by the House of Nobles and the House of Representatives in joint ballot.” Kamehameha III proclaimed his adopted son, Alexander Liholiho, to be his heir apparent after receiving confirmation from the Nobles in 1853. Alexander ascended to the Throne upon the death of King Kamehameha III on December 15, 1854.

King Kamehameha V ascended to the Throne through the process of appointment by the Premier (Kuhina Nui) Victoria Kamamalu, and confirmation by the Nobles in 1863, because Kamehameha IV had no surviving children. His son and heir, Prince Albert Kamehameha, died at the age of four

King Kamehameha V ascended to the Throne through the process of appointment by the Premier (Kuhina Nui) Victoria Kamamalu, and confirmation by the Nobles in 1863, because Kamehameha IV had no surviving children. His son and heir, Prince Albert Kamehameha, died at the age of four  on August 27, 1862. Since the young Prince’s death, Kamehameha IV did not appoint a successor before he died on November 30, 1863. According to the 1852 Constitution, Article 47 provided, “Whenever the throne shall become vacant by reason of the King’s death…the Kuhina Nui, for the time being, shall…perform all the duties incumbent on the King, and shall have and exercise all the powers, which by this Constitution are vested in the King.”

on August 27, 1862. Since the young Prince’s death, Kamehameha IV did not appoint a successor before he died on November 30, 1863. According to the 1852 Constitution, Article 47 provided, “Whenever the throne shall become vacant by reason of the King’s death…the Kuhina Nui, for the time being, shall…perform all the duties incumbent on the King, and shall have and exercise all the powers, which by this Constitution are vested in the King.”

In 1864, a new constitution was promulgated by King Kamehameha V, and Article 22 of the 1864 Constitution provides that, “The Crown is hereby permanently confirmed to His Majesty Kamehameha V. and to the Heirs of His body lawfully begotten, and to their lawful Descendants in a direct line; failing whom, the Crown shall descend to Her Royal Highness the Princess Victoria Kamamalu Kaahumanu, and the heirs of her body, lawfully begotten, and their lawful descendants in a direct line. The Succession shall be to the senior male child, and to the heirs of his body; failing a male child, the succession shall be to the senior female child, and to the heirs of her body.” Princess Kamamalu died on May 29, 1866 without any lineal descendants, leaving the successors to the Throne solely with King Kamehameha V.

Since Kamehameha V had no children, Article 22 of the 1864 Constitution provides that a “successor shall be the person whom the Sovereign shall appoint with the consent of the Nobles, and publicly proclaim as such during the King’s life; but should there be no such appointment and proclamation, and the Throne should become vacant, then the Cabinet Council, immediately after the occurring of such vacancy, shall cause a meeting of the Legislative Assembly, who shall elect by ballot some native Ali‘i of the Kingdom as Successor to the Throne.” The Cabinet Council replaced the function of the Premier (Kuhina Nui) under the former constitution, whose office was repealed by the 1864 Constitution, and according to Article 33 would serve as a Council of Regency.

On December 11, 1872, Kamehameha V died without children and he did not appoint a successor. Kamehameha V’s Cabinet, as a Council of Regency, convened the Legislative Assembly in special session on January 8, 1873. A regent is a person or persons who serve in the absence of a monarch. In their speech to the Legislature, the Council stated:

“His late Majesty did not appoint any successor in the mode set forth in the Constitution, with the consent of the Nobles or make Proclamation thereof during his life. There having been no such appointment or Proclamation, the Throne became vacant, and the Cabinet Council immediately thereupon considered the form of the Constitution in such case made and provided, and Ordered—That a meeting of the Legislative Assembly be caused to be holden at the Court House in Honolulu, on Wednesday which will be the eighth day of January, A.D. 1873, at 12 o’clock noon; and of this order all Members of the Legislative Assembly will take notice and govern themselves accordingly. By virtue of this Order you have been assembled, to elect by ballot, some native Ali‘i of this Kingdom as Successor to the Throne. Your present authority is limited to this duty, but the newly elected Sovereign may require your services after his accession.”

On that day the Legislature elected Lunalilo as King. From December 11, 1872 to January 8, 1873, the Kingdom was headed by a Council of Regency. Article 33 of the 1864 Constitution provides that “the Cabinet Council at the time of such decease shall be a Council of Regency…who shall administer the Government in the name of the King, and exercise all the Powers which are Constitutionally vested in the King.”

On that day the Legislature elected Lunalilo as King. From December 11, 1872 to January 8, 1873, the Kingdom was headed by a Council of Regency. Article 33 of the 1864 Constitution provides that “the Cabinet Council at the time of such decease shall be a Council of Regency…who shall administer the Government in the name of the King, and exercise all the Powers which are Constitutionally vested in the King.”

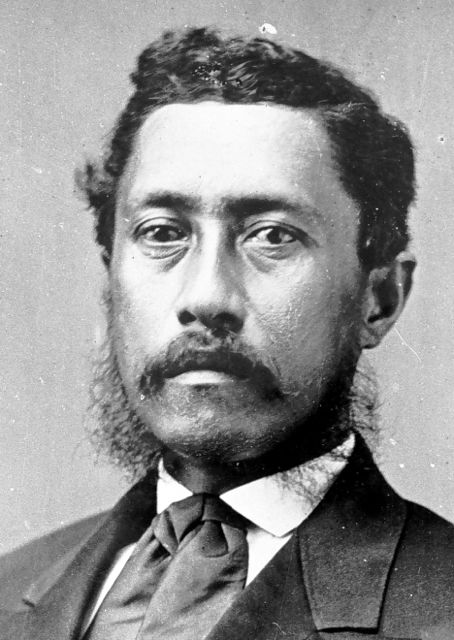

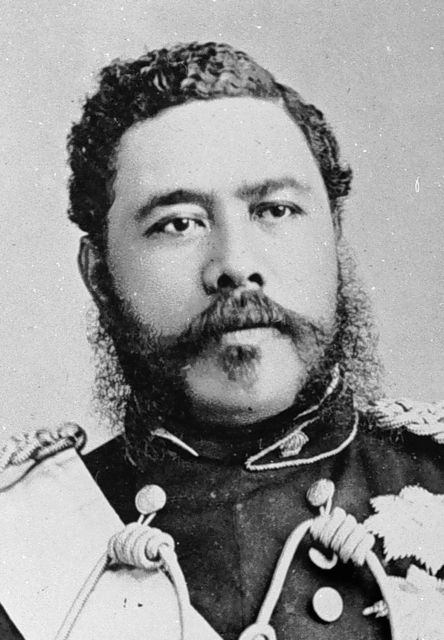

The Legislative Assembly convened again in special session on February 12, 1874 and elected King Kalakaua after Lunalilo, who died without children, failed to appoint a successor. Upon ascension to the Throne, King Kalakaua appointed his brother Prince William Pitt Leleiohoku as his heir apparent and received confirmation from the Nobles. Leleiohoku died April 10, 1877, which prompted

The Legislative Assembly convened again in special session on February 12, 1874 and elected King Kalakaua after Lunalilo, who died without children, failed to appoint a successor. Upon ascension to the Throne, King Kalakaua appointed his brother Prince William Pitt Leleiohoku as his heir apparent and received confirmation from the Nobles. Leleiohoku died April 10, 1877, which prompted  Kalakaua to immediately appoint his sister on the same day, Princess Lili‘uokalani, as his heir apparent and he received confirmation from the Nobles. An heir apparent is a person who is first in line of succession to the Throne according to Hawaiian law and cannot be displaced. An heir presumptive, however, is the person, male or female, entitled to succeed to the Throne, but can be replaced by an heir apparent pronounced according to Hawaiian law.

Kalakaua to immediately appoint his sister on the same day, Princess Lili‘uokalani, as his heir apparent and he received confirmation from the Nobles. An heir apparent is a person who is first in line of succession to the Throne according to Hawaiian law and cannot be displaced. An heir presumptive, however, is the person, male or female, entitled to succeed to the Throne, but can be replaced by an heir apparent pronounced according to Hawaiian law.

When the Legislative Assembly elected King Kalakaua in 1874, a new Stirps had effectively replaced the former Stirps, being the Kamehameha dynasty, with the Keawe-a-Heulu dynasty. Although Lunalilo was an elected King, he was of the Kamehameha dynasty, through Kamehameha’s father, Keoua. Stirps is a direct “line descending from a common ancestor,” and applies to monarchical dynasties. The Stirps for the Kamehameha Dynasty was a direct line from Kamehameha with Keopuolani, being the highest ranking of his wives. Lunalilo was not a direct descendant of Kamehameha, but a direct descendant of Kamehameha’s father, Keoua, whose son, Kalaimamahu, was Kamehameha’s half-brother.

Keawe-a-Heulu was one of the four counselor chiefs to Kamehameha I when the  islands were consolidated under one kingdom. The other three counselor chiefs were Ke‘eaumoku, Kamanawa and Kame‘eiamoku. Ke‘eaumoku was the father of Ka‘ahumanu, one of Kamehameha’s wives and who later served as Prime Minister after Kamehameha’s death in 1819. Kamanawa and Kame‘eiamoku were brothers and are also represented in the Hawaiian Kingdom’s coat of arms.

islands were consolidated under one kingdom. The other three counselor chiefs were Ke‘eaumoku, Kamanawa and Kame‘eiamoku. Ke‘eaumoku was the father of Ka‘ahumanu, one of Kamehameha’s wives and who later served as Prime Minister after Kamehameha’s death in 1819. Kamanawa and Kame‘eiamoku were brothers and are also represented in the Hawaiian Kingdom’s coat of arms.

The Kamehameha dynasty also included the descendants of Kamehameha’s other wives, other than Keopuolani who was the mother of Kamehameha II and III, and the young Princess Nahienaena. These wives and children included: Peleuli who had Maheha Kapulikoliko, Kahoanoku Kina‘u, Kaiko‘olani and Kiliwehi; Kaheiheimalie who had Kamamalu and Kina‘u, who was the mother of Kamehameha IV and V, and Premier Victoria Kamamalu.

In 1883, the Keawe-a-Heulu Stirps was formally declared at the Coronation of King Kalakaua and Queen Kapi‘olani. Princess Lili‘uokalani as the heir apparent, and the heirs presumptive, being Princess Virginia Kapo‘oloku Po‘omaikelani, Princess Kinoiki, Princess Victoria Kawekiu Kai‘ulani Lunalilo Kalaninuiahilapalapa, Prince David Kawananakoa, Prince Edward Abnel Keli‘iahonui, and Prince Jonah Kuhio Kalaniana‘ole comprised the new royal lineage.

Queen Lili‘uokalani appointed Princess Ka‘iulani as her heir apparent in 1891, but was unable to get confirmation by the Nobles because they were prevented from entering the Legislative Assembly as a result of the so-called 1887 bayonet constitution that began the insurgency. In 1917, Queen Lili‘uokalani died with no such appointment or Proclamation leaving the Throne vacant. After the Queen’s death, only Prince Kuhio was left of the heirs presumptive. All the rest had died. Of the heirs presumptive, only Prince David Kawananakoa died with lineal descendants, but these lineal descendants did not inherit the title of heirs presumptive because they were not proclaimed as such by a reigning Monarch, as King Kalakaua did by proclamation in 1883. While these lineal descendants have no claim to the Throne, they are part of the Estate of the Ali‘i (Chiefs).

Queen Lili‘uokalani appointed Princess Ka‘iulani as her heir apparent in 1891, but was unable to get confirmation by the Nobles because they were prevented from entering the Legislative Assembly as a result of the so-called 1887 bayonet constitution that began the insurgency. In 1917, Queen Lili‘uokalani died with no such appointment or Proclamation leaving the Throne vacant. After the Queen’s death, only Prince Kuhio was left of the heirs presumptive. All the rest had died. Of the heirs presumptive, only Prince David Kawananakoa died with lineal descendants, but these lineal descendants did not inherit the title of heirs presumptive because they were not proclaimed as such by a reigning Monarch, as King Kalakaua did by proclamation in 1883. While these lineal descendants have no claim to the Throne, they are part of the Estate of the Ali‘i (Chiefs).

Crown Lands

Under the 1848 Great Mahele (Division), the King and Chiefs divided their interest between themselves and the Government. Under an Act Act relating to the lands of His Majesty the King and of the Government of June 7, 1848, the King separated his lands to be called Crown lands from the Government. In the Act it stated:

Know all men by these presents, that I, Kamehameha III, by the grace of God, King of the Hawaiian Islands, have given this day of my own free will and have made over and set apart forever to the chiefs and people the larger part of my royal land, for the use and benefit of the Hawaiian Government, therefore by this instrument I hereby retain (or reserve) for myself and for my heirs and successors forever, my lands inscribed at pages 178, 182, 184, 186, 190, 194, 200, 204, 206, 210, 212, 214, 216, 218, 220, 222, of this book, these lands are set apart for me and for my heirs and successors forever, as my own property exclusively.

The “book” Kamehameha was referencing the page numbers was the 1848 Buke Mahele also called the Mahele Book.

In 1863, the Hawaiian Kingdom Supreme Court decided a case titled In the Matter of the Estate of His Majesty Kamehameha IV, 2 Haw. 715 (1863). The case centered on dower rights of Queen Kalama wife of Kamehameha III and Queen Emma wife of Kamehameha IV. The case also clarified who are the successors to the nearly one million acres of Crown land. The Supreme Court stated:

By the said Act, which is entitled “An Act relating to the lands of his Majesty the King and of the Government,” the lands reserved to the then reigning sovereign, descend in fee, the inheritance being limited to the successors to the throne, each successive possessor having the right to dispose of the same as private property.

The heirs and successors to the Crown lands are successors to the throne and not the family. In 1864, Kamehameha V asked the Legislature to remove all encumbrances such as mortgage liens on the property that had greatly encumbered the Crown lands.

That year on January 3, the Legislature passed An Act to Relieve the Royal Domain from Encumbrances (January 3, 1865).This Act authorized the Minister of Finance to issue government bonds up to $30,000.00, and the money received through the bonds would pay off the debt lenders had on the Crown in order to release the mortgages. After the debts were cleared, the Act made Crown lands inalienable and limited the ownership of tenants to 30 year leases. By making the Crown lands inalienable they were no longer capable of being mortgaged.

The Act also established a Board of Commissioners of Crown Lands who collected the lease rent. The Commissioners of Crown Lands managed the purse of the Crown. There was no tax that the people paid for to maintain the office of the Crown.

Currently, there are pretenders to the Estate of the Crown. Some claims are well known, while others are not, but all claims to the Crown lands have no basis in Hawaiian law because Her late Majesty Queen Lili‘uokalani did not appoint and thereafter proclaim her successor in accordance with the law as it was done in the past. The office of the Crown can only be filled by an election by the Legislative Assembly as it was done in the case of King Lunalilo in 1873 and King Kalakaua in 1874.

The Estate of Nobles (Chiefs)

The political class of Ali‘i is an integral component of the Hawaiian Kingdom and its government and has its origin deeply rooted in Polynesian society. The entire land system of the Kingdom that continues to exist today is grounded and based on actions taken by the Ali‘i such as the granting of Royal Patents, Land Commission Awards, and the Great Land Division (Mahele) between the Government and Chiefs, which also set the terms of division between both the Government and Chiefs and native tenants desiring to get a fee-simple title to their lands.

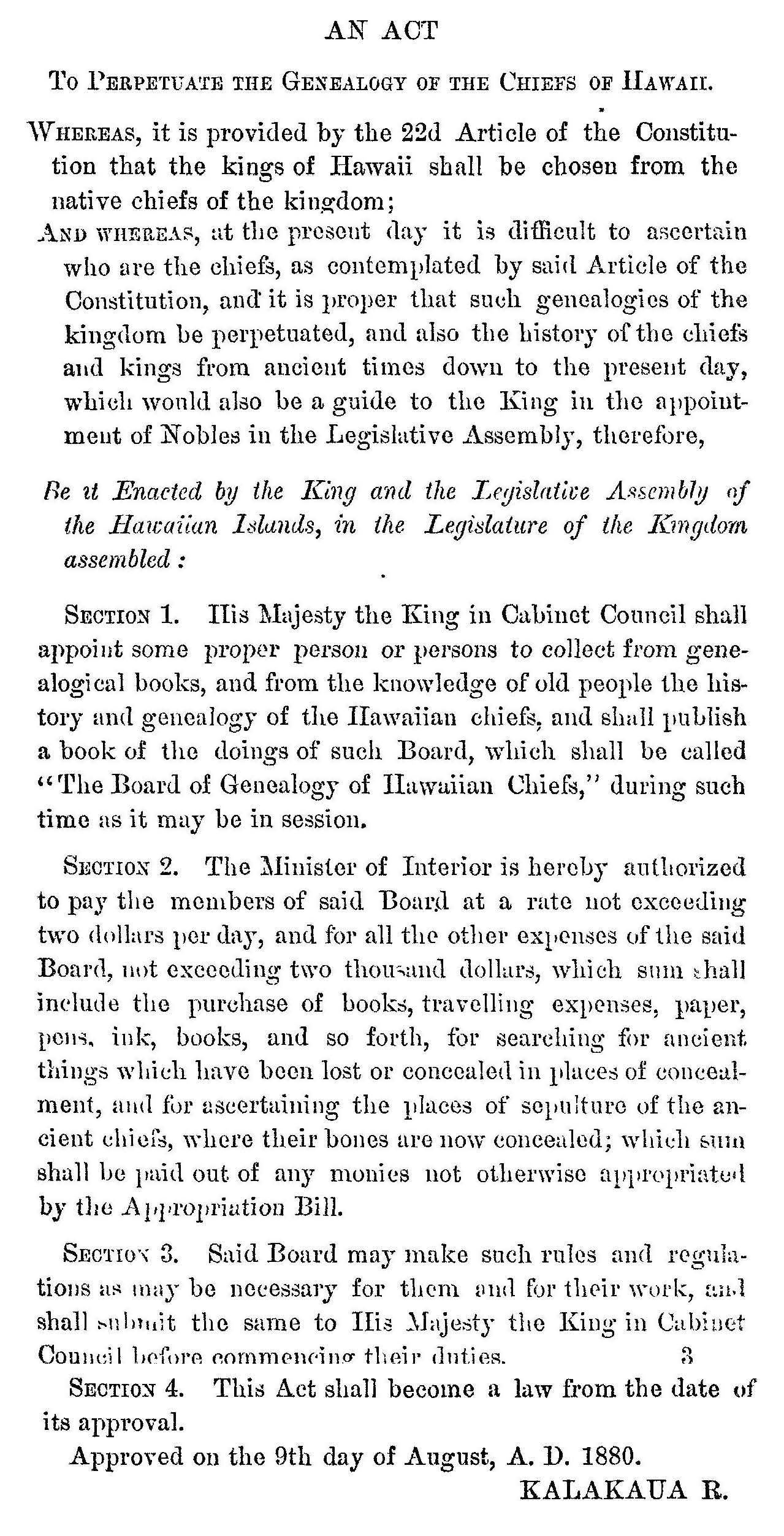

In 1880, confusion as to who comprises the Hawaiian nobility got the Hawaiian Legislature to enact “An Act to Perpetuate the Genealogy of the Chiefs of Hawaii.” In the preamble of the act it stated, “at the present day it is difficult to ascertain who are the chiefs, as contemplated by said Article of the Constitution, and it is proper that such genealogies of the kingdom be perpetuated.”

According to the Rules of the Board, their principle duties are: “1. To gather, revise, correct and record the Genealogy of Chiefs. 2. To gather, revise, correct and record all published and unpublished Ancient Hawaiian History. 3. To gather, revise, correct and record all published and unpublished Meles (Songs), and also to ascertain the object and the spirit of the Meles, the age and the History of the period when composed and to note the same on the Record Book. 4. To record all the tabu customs of the Mois (Kings) and Chiefs.”

According to the Rules of the Board, their principle duties are: “1. To gather, revise, correct and record the Genealogy of Chiefs. 2. To gather, revise, correct and record all published and unpublished Ancient Hawaiian History. 3. To gather, revise, correct and record all published and unpublished Meles (Songs), and also to ascertain the object and the spirit of the Meles, the age and the History of the period when composed and to note the same on the Record Book. 4. To record all the tabu customs of the Mois (Kings) and Chiefs.”

In its Report in 1884, the Board stated it was examining copies of genealogical books by Kamokuiki, Kaoo, Kaunahi, Unauna, Hakaleleponi, Piianaia, Kalaualu and David Malo, and that the “Board has not entered into revision of these books and those written by foreign historians as the time has been taken up mostly in attesting the genealogy of those that have applied to have their genealogy established.” The Board also reported, that it “has avoided entering into controversies with the genealogical discussions that have been going on for a year or more in the local Hawaiian newspapers, as these discussions have been more or less conducted in a partisan spirit instead of on scientific principles. They loose the merit of usefulness by the hostilities assumed by the contending writers.”

On July 5, 1887, the newly appointed Cabinet Council and two members of the Supreme Court committed the high crime of treason by coercing King Kalakaua to sign a new constitution under threat of assassination. This so-called constitution came to be known as the Bayonet Constitution and was never submitted to the Legislative Assembly for approval, which is required under law. Hawaiian constitutional law provides that any proposed change to the constitution must be submitted to the Legislative Assembly, and upon majority agreement, would be deferred to the next legislative session for action. Once the next legislature convened, and the proposed amendment or amendments were “agreed to by two-thirds of all members of the Legislative Assembly, and be approved by the King, such amendment or amendments shall become part of the Constitution of this country (Article 80, 1864 Constitution).”

This so-called constitution was drafted by a select group of twenty individuals and effectively placed control of the Legislature and Cabinet in the hands of individuals who held foreign allegiances, which led to the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian government by the United States of America. The leader of this insurgency, Lorrin Thruston, was the Minister of the Interior, and he refused to fund the Board of Genealogists