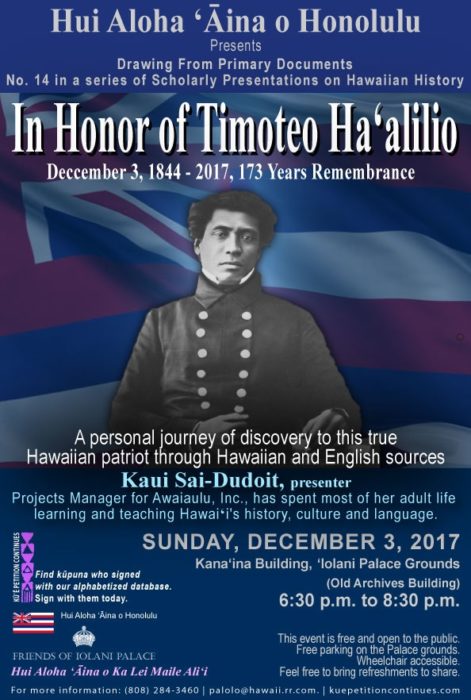

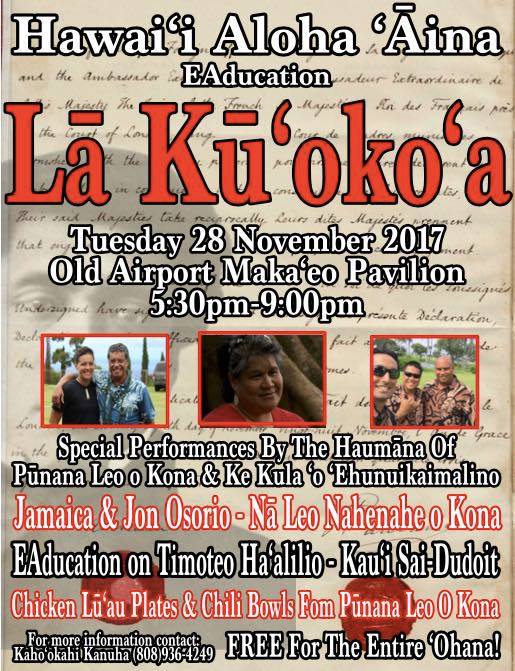

Kau‘i Sai-Dudoit to Present on Timoteo Ha‘alilio

1

The term “war crimes” was not coined until 1919 after the First World War ended in Europe. A common misunderstanding is that individuals whose criminal conduct constituted a war crime could only be prosecuted if that conduct arose after 1919. This is not the case because under the principles of international law, war crimes could have been committed since, at least, 1874, when delegates of fifteen European States gathered in Brussels, Belgium, at the request of Russia’s Czar Alexander II, in order to draft an international agreement concerning the laws and customs of war.

Among these fifteen States an agreement was made, but it wasn’t ratified by these States. It did, however, lead to the adoption of the Manual of the Laws and Customs of War at Oxford in 1880. Both the Brussels Declaration and the Oxford Manual formed the basis of the two Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907.

At the Peace Conference held in The Hague, Netherlands in 1899, countries from across the world met in order to codify what was already accepted as customary international law regarding the rules of warfare and occupation, which is known today as international humanitarian law. The cornerstone of international humanitarian law during the occupation of a State is the duty of the occupying State to administer the laws of the occupied State, which is reflected in Article 43 of the 1899 Hague Convention, II.

Article 43 states, “The authority of the legitimate power having actually passed into the hands of the occupant, the latter shall take all steps in his power to re-establish and insure, as far as possible, public order and safety, while respecting, unless absolutely prevented, the laws in force in the country.” This article is a combination of Article 2, “The authority of the legitimate Power being suspended and having in fact passed into the hands of the occupants, the latter shall take all the measures in his power to restore and ensure, as far as possible, public order and safety,” and Article 3, “With this object he shall maintain the laws which were in force in the country in time of peace, and shall not modify, suspend or replace them unless necessary,” of the 1874 Brussels Declaration. The Brussels Declaration was referenced in the Preamble of the 1899 Hague Convention, II. Article 43 was restated in the 1907 Hague Convention, IV.

Although the United States signed and ratified both the 1899 and the 1907 Hague Regulations, which post-date the occupation of the Hawaiian Islands, the “text of Article 43,” according to Benvenisti, author of The International Law of Occupation (1993), p. 8, “was accepted by scholars as mere reiteration of the older law, and subsequently the article was generally recognized as expressing customary international law.” Graber, author of The Development of the Law of Belligerent Occupation: 1863-1914 (1949), p. 143, also states, that “nothing distinguishes the writing of the period following the 1899 Hague code from the writing prior to that code.”

As an occupying State, the United States was obligated to establish a military government, whose purpose would be to provisionally administer the laws of the occupied State—the Hawaiian Kingdom—until a treaty of peace or agreement to terminate the occupation has been done. According to United States Army Field Manual 27-10 (1956), sec. 362, “Military government is the form of administration by which an occupying power exercises governmental authority over occupied territory.” The administration of occupied territory is set forth in the Hague Regulations, being Section III of the 1907 HC IV. According to Schwarzenberger, author of “The Law of Belligerent Occupation: Basic Issues,” 30 Nordisk Tidsskrift Int’l Ret (1960), p. 11, “Section III of the Hague Regulations … was declaratory of international customary law.”

Also, consistent with what was generally considered the international law of occupation in force at the time of the Spanish-American War, the “military governments established in the territories occupied by the armies of the United States were instructed to apply, as far as possible, the local laws and to utilize, as far as seemed wise, the services of the local Spanish officials (Munroe Smith, “Record of Political Events,” 13(4) Political Science Quarterly (1898), 745, p. 748).”

Many other authorities also viewed the 1907 Hague Regulations as mere codification of customary international law, which was applicable at the time of the overthrow of the Hawaiian government and subsequent occupation. These include: Gerhard von Glahn, The Occupation of Enemy Territory: A Commentary on the Law and Practice of Belligerent Occupation (1957), 95; David Kretzmer, The Occupation of Justice: The Supreme Court of Israel and the Occupied Territories (2002), 57; Ludwig von Kohler, The Administration of the Occupied Territories, vol. I, (1942) 2; United States Judge Advocate General’s School Tex No. 11, Law of Belligerent Occupation (1944), 2 (stating that “Section III of the Hague Regulations is in substance a codification of customary law and its principles are binding signatories and non-signatories alike”).

The contracting States to the 1899 Hague Convention, II, also recognized that they were codifying existing customary international law and not creating new law. In its Preamble, it states, “Until a more complete code of the laws of war is issued, the High Contracting Parties think it right to declare that in cases not included in the Regulations adopted by them, populations and belligerents remain under the protection and empire of the principles of international law, as they result from the usages established between civilized nations, from the laws of humanity, and the requirements of the public conscience.” This particular provision of the Preamble has come to be known as the Martens clause. Professor von Martens was the Russian delegate at the 1899 Hague Peace Conference, that recommended this provision be placed in the Preamble after the delegates were unable to agree on the status of civilians who took up arms against the occupying State.

The Commission on the Responsibility of the Authors of the War and on Enforcement of Penalties was established at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 after World War I. Its role was to investigate the allegations of war crimes and recommend who should be prosecuted. In its report (Pamphlet No. 32, p. 18), the Commission identified 32 war crimes, two of which were “usurpation of sovereignty during military occupation” and “attempts to denationalise the inhabitants of occupied territory.”

Although these crimes were not specifically identified in 1899 Hague Convention, II, or the 1907 Hague Convention, IV, the Commission relied solely on the Martens clause in the 1899 Hague Convention, II. In other words, the Commission concluded that the war crimes of “usurpation of sovereignty during military occupation” and “attempts to denationalise the inhabitants of occupied territory” were recognized under principles of international law since at least the 1874 Brussels Declaration.

Under the war crime of usurpation of sovereignty during military occupation, the Commission concluded that from 1915-1918, Bulgaria engaged in criminal conduct when it “Proclaimed that the Serbian State no longer existed, and that Serbian territory had become Bulgarian,” and that “official orders show efforts of Bulgarisation (Pamphlet No. 32, p. 38).” The Commission also concluded Bulgaria committed the following acts of usurpation of sovereignty:

The Commission also concluded that Austrian and German authorities also engaged in the following criminal conduct of usurpation of sovereignty during military occupation from 1915 to 1918 during the occupation of Serbia (Pamphlet No. 32, p. 38).

Under the war crime of attempts to denationalize the inhabitants of occupied territory, the Commission concluded that from 1915-1918, Bulgaria engaged in the following criminal conduct in occupied Serbia (Pamphlet No. 32, p. 39).

The Commission also concluded that Austrian and German authorities also engaged in the following criminal conduct of attempts to denationalize the inhabitants of occupied territory from 1915 to 1918 during the occupation of Serbia (Pamphlet No. 32, p. 39).

The prosecution of German officials and their Allies for war crimes committed during World War I, however, was dismal. Of 5,000 individuals reported for war crimes only 12 were tried and 6 were convicted. Despite this failure, it was the beginning of imposing criminal liability on individuals for violations of international law that eventually became firmly grounded after the Second World War, which led to war crimes legislation in countries who were contracting parties to the 1949 Geneva Conventions, and also the establishment of the International Criminal Court.

Under the principles of international law, officials of the United States were capable of committing war crimes when the Hawaiian Kingdom was first invaded on January 16, 1893 and occupied since January 17 when the Hawaiian government was unlawfully seized. The criminal conduct committed by German, Austrian and Bulgarian officials against Serbia and its people during the First World War (1914-1918) are very similar to the criminal conduct by the United States since January 16, 1893 against the Hawaiian Kingdom and its people.

The International Commission of Inquiry in Incidents of War Crimes in the Hawaiian Islands—The Larsen Case that stems from the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom arbitration held at the Permanent Court of Arbitration from 1999-2001, will be holding its first hearing on the grounds of ‘Iolani Palace at the Kana‘ina Building on January 16 and 17, 2018.

The hearing will be closed to the public, but the proceedings will be live streamed on the Internet. At the core of these proceedings will be the unlawful imposition of American laws that led to the unfair trial, unlawful confinement and pillaging of Lance Paul Larsen, a Hawaiian subject and victim of war crimes committed against him by the United States through its armed force—the State of Hawai‘i. These war crimes were committed in 1999.

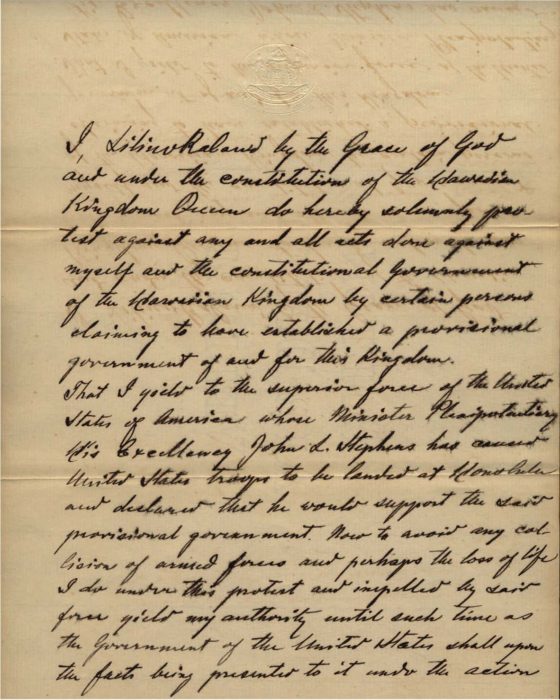

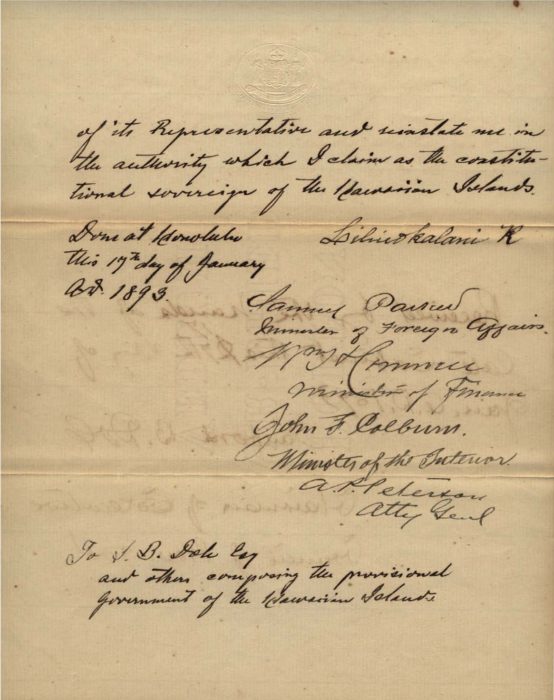

These two days will mark 125 years of the American invasion of the Hawaiian Kingdom on January 16th and the conditional surrender of the Hawaiian government by Queen Lili‘uokalani on January 17th calling upon the President of the United States to investigate the unlawful actions taken by its diplomat who ordered the landing of U.S. troops. While in the Palace, the Queen drafted the following conditional surrender to the United States:

These two days will mark 125 years of the American invasion of the Hawaiian Kingdom on January 16th and the conditional surrender of the Hawaiian government by Queen Lili‘uokalani on January 17th calling upon the President of the United States to investigate the unlawful actions taken by its diplomat who ordered the landing of U.S. troops. While in the Palace, the Queen drafted the following conditional surrender to the United States:

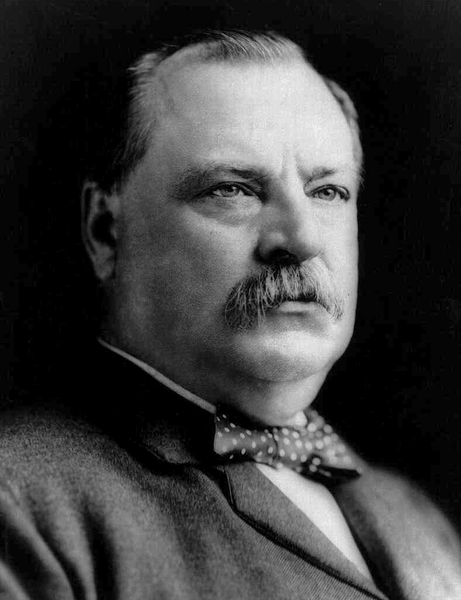

After investigating the overthrow of the Hawaiian government, President Cleveland notified Congress on December 18, 1893, that the “military demonstration upon the soil of Honolulu was of itself an act of war.” Cleveland noted “that on the 16th day of January, 1893, between four and five o’clock in the afternoon, a detachment of marines from the United States steamer Boston, with two pieces of artillery, landed at Honolulu. The men, upwards of 160 in all, were supplied with double cartridge belts filled with ammunition and with haversacks and canteens, and were accompanied by a hospital corps with stretchers and medical supplies.” He then concluded that by “an act of war, committed with the participation of a diplomatic representative of the United States and without authority of Congress, the Government of a feeble but friendly and confiding people has been overthrown.”

After investigating the overthrow of the Hawaiian government, President Cleveland notified Congress on December 18, 1893, that the “military demonstration upon the soil of Honolulu was of itself an act of war.” Cleveland noted “that on the 16th day of January, 1893, between four and five o’clock in the afternoon, a detachment of marines from the United States steamer Boston, with two pieces of artillery, landed at Honolulu. The men, upwards of 160 in all, were supplied with double cartridge belts filled with ammunition and with haversacks and canteens, and were accompanied by a hospital corps with stretchers and medical supplies.” He then concluded that by “an act of war, committed with the participation of a diplomatic representative of the United States and without authority of Congress, the Government of a feeble but friendly and confiding people has been overthrown.”

Under international law, when a Head of State concludes that an act of war was committed by its military on foreign soil it changes the state of affairs from a state of peace to a state of war. According to McDougal and Feliciano, authors of “The Initiation of Coercion: A Multi-temporal Analysis,” 52 American Journal of International Law (1958) p. 247, a state of war “automatically brings about the full operation of all the rules of war and neutrality.” And, according to Venturini, author of “The Temporal Scope of Application of the Conventions,” in Andrew Clapham, Paola Gaeta, and Marco Sassòli (eds), The 1949 Geneva Conventions: A Commentary (2015), p. 52, if “an armed conflict occurs, the law of armed conflict must be applied from the beginning until the end, when the law of peace resumes in full effect.”

Koman, author of The Right of Conquest: The Acquisition of Territory by Force in International Law and Practice (1996), p. 224, states that “the laws of war … continue to apply in the occupied territory even after the achievement of military victory, until either the occupant withdraws or a treaty of peace is concluded which transfers sovereignty to the occupant.” In the Tadić case, decision on the Defense Motion for Interlocutory Appeal on Jurisdiction (Appeals Chamber), October 2, 1995, §70, the International Criminal Court for the Former Yugoslavia indicated that the laws of war—international humanitarian law—applies from “the initiation of … armed conflicts and extends beyond the cessation of hostilities until a general conclusion of peace is reached.”

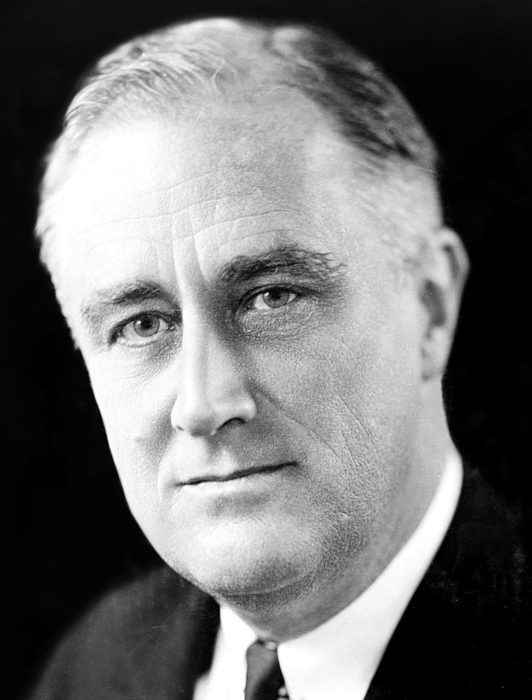

The political determination by President Cleveland, regarding the actions taken by the military forces of the United States since January 16, 1893, was the same as the political determination by President Roosevelt regarding actions taken by the military forces of Japan on December 7, 1945 in its attack of Pearl Harbor. On December 8, 1941, President Roosevelt notified Congress:

The political determination by President Cleveland, regarding the actions taken by the military forces of the United States since January 16, 1893, was the same as the political determination by President Roosevelt regarding actions taken by the military forces of Japan on December 7, 1945 in its attack of Pearl Harbor. On December 8, 1941, President Roosevelt notified Congress:

“Yesterday, December 7th, 1941—a date which will live in infamy—the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan. The United States was at peace with that nation… [and] since the unprovoked and dastardly attack by Japan on Sunday, December 7th, 1941, a state of war has existed between the United States and the Japanese Empire.”

Both political determinations by these Presidents created a “state of war” for the United States under international law. Japan entered into a peace treaty in 1951, which came into effect the following year. However, there is no treaty of peace between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States. Consequently, the United States was bound by customary international law to administer the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom until a peace treaty has been negotiated. After Japan signed a treaty of surrender in 1945, the United States occupied Japan until 1952 whereby a military government was formed, with General MacArthur as its military governor, and who administered Japanese law and not American law.

The deliberate failure by the United States to administer Hawaiian Kingdom law has led to the unlawful imposition of American laws in the Hawaiian Kingdom that formed the basis of the dispute between Lance Larsen, a Hawaiian subject, and the Provisional Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom at the Permanent Court of Arbitration, The Hague, Netherlands. The unlawful imposition of American laws within Hawaiian territory is the war crime of “usurpation of sovereignty” of the occupied State. And the failure to comply with the law of occupation in the administration of Hawaiian Law according to Article 43 of the 1907 Hague Convention, IV, is a war crime as well.

Professor William Schabas is the final commissioner to be appointed as a member of the International Commission of Inquiry in Incidents of War Crimes in the Hawaiian Islands—The Larsen Case that stems from the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom arbitration held at the Permanent Court of Arbitration from 1999-2001. Professor Schabas was appointed by the Provisional Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom and Dexter Kaiama, attorney for Lance Larsen, on October 14, 2017.

Professor William Schabas is the final commissioner to be appointed as a member of the International Commission of Inquiry in Incidents of War Crimes in the Hawaiian Islands—The Larsen Case that stems from the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom arbitration held at the Permanent Court of Arbitration from 1999-2001. Professor Schabas was appointed by the Provisional Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom and Dexter Kaiama, attorney for Lance Larsen, on October 14, 2017.

The Commission of Inquiry has been duly constituted which comprises of Professor Schabas from Middlesex University London and the University of Leiden, Professor Pierre D’Argent from the University of Louvain and Professor Jean d’Aspremont from the University of Manchester.

In these proceedings, the Provisional Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom is represented by Dr. Keanu Sai, as Agent, Professor Federico Lenzerini, Ph.D., as Deputy-Agent, and Ben Emmerson, QC, from the Matrix Chambers in London, as Counsel.

William Schabas is professor of international law at Middlesex University in London. He is also professor of international criminal law and human rights at the University of Leiden. Professor Schabas is also emeritus professor of human rights law at the National University of Ireland Galway and honorary chairman of the Irish Centre for Human Rights, invited visiting scholar at the Paris School of International Affairs (Sciences Politiques), honorary professor at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing, visiting fellow of Kellogg College of the University of Oxford, visiting fellow of Northumbria University, and professeur associé at the Université du Québec à Montréal. Prof. Schabas is a ‘door tenant’ at the chambers of 9 Bedford Row, in London.

Professor Schabas holds BA and MA degrees in history from the University of Toronto and LLB, LLM and LLD degrees from the University of Montreal, as well as honorary doctorates in law from several universities. He is the author of more than twenty books dealing in whole or in part with international human rights law, including: The Universal Declaration of Human Rights: travaux préparatoires (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013); Unimaginable Atrocities, Justice, Politics and Rights at the War Crimes Tribunals (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), The International Criminal Court: A Commentary on the Rome Statute (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), Introduction to the International Criminal Court (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011, 4th ed.), Genocide in International Law (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2nd ed., 2009) and The Abolition of the Death Penalty in International Law (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2003, 3rd ed.). He has also published more than 350 articles in academic journals, principally in the field of international human rights law and international criminal law. His writings have been translated into Russian, German, Spanish, Portuguese, Chinese, Japanese, Arabic, Persian, Turkish, Nepali and Albanian.

Professor Schabas is editor-in-chief of Criminal Law Forum, the quarterly journal of the International Society for the Reform of Criminal Law.He is President of the Irish Branch of the International Law Association and chair of the International Institute for Criminal Investigation. From 2002 to 2004 he served as one of three international members of the Sierra Leone Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Professor Schabas has worked as a consultant on capital punishment for the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime, and drafted the 2010 and 2015 reports of the Secretary-General on the status of the death penalty.

Professor Schabas was named an Officer of the Order of Canada in 2006. He was elected a member of the Royal Irish Academy in 2007. He has been awarded the Vespasian V. Pella Medal for International Criminal Justice of the Association internationale de droit pénal, and the Gold Medal in the Social Sciences of the Royal Irish Academy.

The Commission of Inquiry will hold its first hearing in Honolulu on January 16 and 17, 2018, which marks the 125th year of the United States’ invasion on the 16th, the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian government on the 17th, and the ensuing prolonged occupation since. According to Article III of the Special Agreement to form an International Commission of Inquiry:

“The Commission is requested to determine: First, what is the function and role of the Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom in accordance with the basic norms and framework of international humanitarian law; Second, what are the duties and obligations of the Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom toward Lance Paul Larsen, and, by extension, toward all Hawaiian subjects domiciled in Hawaiian territory and abroad in accordance with the basic norms and framework of international humanitarian law; and, Third, what are the duties and obligations of the Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom toward Protected Persons who are domiciled in Hawaiian territory and those Protected Persons who are transient in accordance with the basic norms and framework of international humanitarian law.”

On October 9, 2017, Dr. Keanu Sai was interviewed on a show “Law Across the Sea” hosted by Mark Shklov who is a practicing attorney. The interview centered on the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom arbitration and the International Commission of Inquiry in Incidents of War Crimes in the Hawaiian Islands—The Larsen Case that stemmed from the arbitration case.

Professor Pierre D’Argent is the second of three commissioners to be appointed as a member of the International Commission of Inquiry in Incidents of War Crimes in the Hawaiian Islands—The Larsen Case that stems from the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom arbitration held at the Permanent Court of Arbitration from 1999-2001. Professor D’Argent was appointed by the Provisional Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom and Dexter Kaiama, attorney for Lance Larsen, on October 8, 2017.

Professor Pierre D’Argent is the second of three commissioners to be appointed as a member of the International Commission of Inquiry in Incidents of War Crimes in the Hawaiian Islands—The Larsen Case that stems from the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom arbitration held at the Permanent Court of Arbitration from 1999-2001. Professor D’Argent was appointed by the Provisional Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom and Dexter Kaiama, attorney for Lance Larsen, on October 8, 2017.

In these proceedings, the Provisional Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom is represented by Dr. Keanu Sai, as Agent, Professor Federico Lenzerini, Ph.D., as Deputy-Agent, and Ben Emmerson, QC, from the Matrix Chambers in London, as Counsel.

Pierre D’Argent is full professor at the University of Louvain in Belgium, where he holds the Public International Law Chair. He is also a guest professor at Leiden University in the Netherlands. He is Associate Member of the Institut de droit international and member of the Brussels Bar, acting as special counsel to Foley Hoag LLP. He specializes in advising and representing states before international courts and tribunals. He appeared as counsel before the International Court of Justice and later served the court as first secretary.

He has published extensively in matters relating to international law and has lectured in many universities around the world. He has been director of studies at The Hague Academy of International Law and has taught a specialized course at the Academy. He has contributed to the UN Audiovisual Library of International Law.

The Commission of Inquiry will hold its first hearing in Honolulu on January 16 and 17, 2018, which marks the 125th year of the United States’ invasion on the 16th, the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian government on the 17th, and the ensuing prolonged occupation since. According to Article III of the Special Agreement to form an International Commission of Inquiry:

“The Commission is requested to determine: First, what is the function and role of the Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom in accordance with the basic norms and framework of international humanitarian law; Second, what are the duties and obligations of the Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom toward Lance Paul Larsen, and, by extension, toward all Hawaiian subjects domiciled in Hawaiian territory and abroad in accordance with the basic norms and framework of international humanitarian law; and, Third, what are the duties and obligations of the Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom toward Protected Persons who are domiciled in Hawaiian territory and those Protected Persons who are transient in accordance with the basic norms and framework of international humanitarian law.”

Professor Jean D’Aspremont is the first of three commissioners to be appointed as a  member of the International Commission of Inquiry in Incidents of War Crimes in the Hawaiian Islands—The Larsen Case that stems from the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom arbitration held at the Permanent Court of Arbitration from 1999-2001. Professor D’Aspremont was appointed by the Provisional Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom and Dexter Kaiama, attorney for Lance Larsen, on October 7, 2017.

member of the International Commission of Inquiry in Incidents of War Crimes in the Hawaiian Islands—The Larsen Case that stems from the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom arbitration held at the Permanent Court of Arbitration from 1999-2001. Professor D’Aspremont was appointed by the Provisional Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom and Dexter Kaiama, attorney for Lance Larsen, on October 7, 2017.

In these proceedings, the Provisional Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom is represented by Dr. Keanu Sai, as Agent, Professor Federico Lenzerini, Ph.D., as Deputy-Agent, and Ben Emmerson, QC, from the Matrix Chambers in London, as Counsel.

Jean d’Aspremont is Professor of Public International Law at the University of Manchester where he founded the Manchester International Law Centre (MILC) with Professor Iain Scobbie. He is General Editor of the Cambridge Studies in International and Comparative Law and director of the Oxford Database on International Organizations. He is a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of the European Journal of International Law. He is series editor of the Melland Schill Studies in International Law.

He used to be Editor-in-Chief of the Leiden Journal of International Law as well as series editor of the Elgar International Law Series. He was guest professor at the Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights (HEID/University of Geneva), the University of Louvain, and the University of Lille. He acted as counsel in proceedings before the International Court of Justice. Before moving to Manchester, he was Associate Professor of International Law at the University of Amsterdam and Assistant Professor of International Law at the University of Leiden. He received his LL.M. from the University of Cambridge and his Ph.D. from the University of Louvain. In 2005-06, he was a Global Research Fellow at New York University (NYU), affiliated with the Institute of International Law and Justice (IILJ).

The Commission of Inquiry will hold its first hearing in Honolulu on January 16 and 17, 2018, which marks the 125th year of the United States’ invasion on the 16th, the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian government on the 17th, and the ensuing prolonged occupation since. According to Article III of the Special Agreement to form an International Commission of Inquiry:

“The Commission is requested to determine: First, what is the function and role of the Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom in accordance with the basic norms and framework of international humanitarian law; Second, what are the duties and obligations of the Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom toward Lance Paul Larsen, and, by extension, toward all Hawaiian subjects domiciled in Hawaiian territory and abroad in accordance with the basic norms and framework of international humanitarian law; and, Third, what are the duties and obligations of the Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom toward Protected Persons who are domiciled in Hawaiian territory and those Protected Persons who are transient in accordance with the basic norms and framework of international humanitarian law.”

Dr. Keanu Sai recently returned from London after meeting with the Matrix Chambers who has joined his legal team in the international commission of inquiry proceedings stemming from the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom (1999-2001) case held under the auspices of the Permanent Court of Arbitration. Matrix Chambers is one of the leading law firms in the United Kingdom and has represented countries before international courts and tribunals.

These proceedings were initiated on January 19, 2017 by Special Agreement between the Provisional Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom and Lance Paul Larsen. Both Parties agreed to the rules provided under Part III—International Commissions of Inquiry (Articles 9-36) of the 1907 Hague Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes. Once the Commission of Inquiry has been formed they will hold their hearings in the Hawaiian Kingdom. The formation of the Commission is moving forward. According to the Special Agreement,

“The Commission is requested to determine: First, what is the function and role of the Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom in accordance with the basic norm and framework of international humanitarian law; and, Second, what are the duties and obligations of the Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom toward Lance Paul Larsen, and, by extension, toward all Hawaiian subjects domiciled in Hawaiian territory and abroad in accordance with the basic norm and framework of international humanitarian law.”

Dr. Sai heads the Hawaiian Kingdom legal team as Agent, Professor Federico Lenzerini from the University of Siena Law School in Italy is the Deputy-Agent, and Ben Emmerson, QC, from the Matrix Chambers is Counsel. Mr. Emmerson is the former United Nations Special Rapporteur on Counter Terrorism and Human Rights. He was also elected by the United Nations General Assembly as one of the Judges for the International Criminal Court for Rwanda and the International Criminal Court for the former Yugoslavia. His expertise is in international criminal law and served as Special Advisor to the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court.

Dr. Sai heads the Hawaiian Kingdom legal team as Agent, Professor Federico Lenzerini from the University of Siena Law School in Italy is the Deputy-Agent, and Ben Emmerson, QC, from the Matrix Chambers is Counsel. Mr. Emmerson is the former United Nations Special Rapporteur on Counter Terrorism and Human Rights. He was also elected by the United Nations General Assembly as one of the Judges for the International Criminal Court for Rwanda and the International Criminal Court for the former Yugoslavia. His expertise is in international criminal law and served as Special Advisor to the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court.

The first allegations of war crimes committed in Hawai‘i, being unfair trial, unlawful confinement and pillaging, were made the subject of an arbitral dispute in Lance Larsen vs. Hawaiian Kingdom at the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA). Oral hearings were held at the PCA on December 7, 8, and 11, 2000. As an intergovernmental organization, the PCA must possess institutional jurisdiction before it can form ad hoc tribunals. The jurisdiction of the PCA is distinguished from the subject-matter jurisdiction of the ad hoc tribunal over the dispute between the parties.

Disputes capable of being accepted under the PCA’s institutional jurisdiction include disputes between: any two or more states; a state and an international organization, such as an agency of the United Nations; two or more international organizations; a state and a private party; and an international organization and a private entity. The PCA accepted the case as a dispute between a state and a private party, and acknowledged the Hawaiian Kingdom as a non-Contracting Power under Article 47 of the 1907 Hague Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes. As stated on the PCA’s website:

“Lance Paul Larsen, a resident of Hawaii, brought a claim against the Hawaiian Kingdom by its Council of Regency (“Hawaiian Kingdom”) on the grounds that the Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom is in continual violation of: (a) its 1849 Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation with the United States of America, as well as the principles of international law laid down in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 1969 and (b) the principles of international comity, for allowing the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws over the claimant’s person within the territorial jurisdiction of the Hawaiian Kingdom.”

The Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom, as it stood on January 17 1893, was restored in 1995, in situ and not in exile. An acting Council of Regency comprised of four Ministers—Interior, Foreign Affairs, Finance and the Attorney General—was established in accordance with the Hawaiian constitution and the doctrine of necessity to serve in the absence of the executive monarch. By virtue of this process a Provisional Government, comprised of officers de facto, was established. According to U.S. constitutional scholar Thomas Cooley,

“A provisional government is supposed to be a government de facto for the time being; a government that in some emergency is set up to preserve order; to continue the relations of the people it acts for with foreign nations until there shall be time and opportunity for the creation of a permanent government. It is not in general supposed to have authority beyond that of a mere temporary nature resulting from some great necessity, and its authority is limited to the necessity.”

Like other governments formed in exile during foreign occupations, the Hawaiian government did not receive its mandate from the Hawaiian citizenry, but rather by virtue of Hawaiian constitutional law, and therefore represents the Hawaiian state. The Provisional Government is not a new government, but rather a restoration of the Hawaiian Government that existed on January 17, 1893, before it was illegally seized and transformed into an insurgency by the United States. In 2001, Bederman and Hilbert reported in the American Journal of International Law,

“At the center of the PCA proceedings was … that the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist and that the Hawaiian Council of Regency (representing the Hawaiian Kingdom) is legally responsible under international law for the protection of Hawaiian subjects, including the claimant. In other words, the Hawaiian Kingdom was legally obligated to protect Larsen from the United States’ ‘unlawful imposition [over him] of [its] municipal laws’ through its political subdivision, the State of Hawaii. As a result of this responsibility, Larsen submitted, the Hawaiian Council of Regency should be liable for any international law violations that the United States had committed against him.”

The Tribunal concluded that it did not possess subject matter jurisdiction in the case because of the indispensible third party rule. The Tribunal explained:

“It follows that the Tribunal cannot determine whether the respondent [the Hawaiian Kingdom] has failed to discharge its obligations towards the claimant [Larsen] without ruling on the legality of the acts of the United States of America. Yet that is precisely what the Monetary Gold principle precludes the Tribunal from doing. As the International Court of Justice explained in the East Timor case, ‘the Court could not rule on the lawfulness of the conduct of a State when its judgment would imply an evaluation of the lawfulness of the conduct of another State which is not a party to the case.’”

The Tribunal, however, acknowledged that the parties to the arbitration could pursue fact-finding. The Tribunal stated, “At one stage of the proceedings the question was raised whether some of the issues which the parties wished to present might not be dealt with by way of a fact-finding process. In addition to its role as a facilitator of international arbitration and conciliation, the Permanent Court of Arbitration has various procedures for fact-finding, both as between States and otherwise.”

The Tribunal noted “that the interstate fact-finding commissions so far held under the auspices of the Permanent Court of Arbitration have not confined themselves to pure questions of fact but have gone on, expressly or by clear implication, to deal with issues of responsibility for those facts.” The Tribunal pointed out that “Part III of each of the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 provide for International Commissions of Inquiry.”

To date, there have only been five international commissions of inquiry held under the auspices of the PCA—the first in 1905, The Dogger Bank Case (Great Britain – Russia), and the last in 1962, Red Crusader’ Incident (Great Britain – Denmark). These commissions of inquiry formed under the 1907 Hague Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes serve in similar fashion to grand juries where they not only inquire into the facts of the case but also assign criminal or civil liability for another court or tribunal to prosecute.

(BIVN) – “This is big,” announced Dr. Keanu Sai in the gymnasium of the Boys & Girls Club in Hilo on Saturday.

Sai, one of several featured speakers in a two day educational seminar organized in celebration of the Hawaiian holiday of La Ho‘iho‘i ‘Ea, was talking about the news that came from the National Education Association’s Annual Meeting and Representative Assembly in Boston, Massachusetts on July 4th.

A group with the Hawai‘i State Teachers Association – the NEA affiliate union representing the public school teachers of Hawaii – successfully convinced the teachers of America to approve New Business Item 37, which stated:

HSTA credited Chris Santomauro, a teacher at Kaneohe Elementary, with introducing the proposal and Uluhani Waialeale, a teacher at Kualapuu charter school on Moloka’i, for presenting an “impassioned and articulate argument in favor of the Hawaiian overthrow measure” which “swayed a majority of teachers from across the country to support it.”

“That’s big. This is not political, this is education,” Sai said as he explained the HSTA proposal to those gathered for his talk in Hilo.

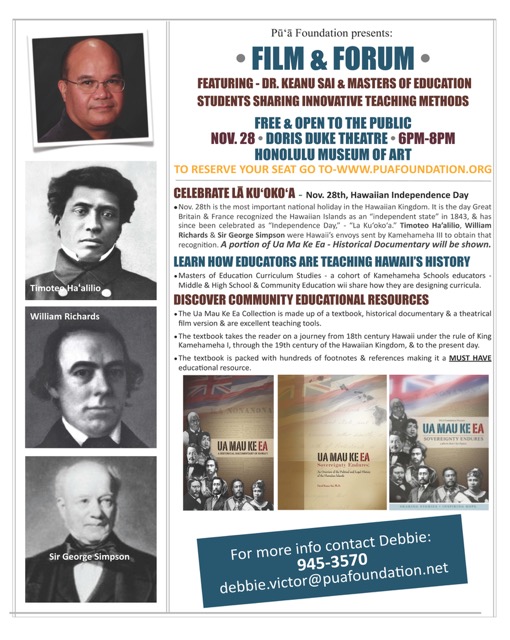

According to Sai, the HSTA Secretary/Treasurer is Amy Perruso, a teacher from Mililani High School. She was one of the first teachers to begin teaching about the illegal overthrow of the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the illegal American occupation that followed. Perruso even teaches from Sai’s textbook, Ua Mau Ke Ea—Sovereignty Endures: An Overview of the Political and Legal History of the Hawaiian Islands.

“I pretty much can guarantee you that the teachers that are teaching about Hawaii’s occupation probably came through one of our classes at the University of Hawaii,” Sai said, claiming he had nothing to do with the HSTA’s plan to draw up the agenda item. “That’s the impact right there,” Sai said, “where they are taking their kuleana and maximizing it.”

Ever since Sai’s first trip to the Permanent Court of Arbitration in 2001, where he represented the Hawaiian Kingdom government in the Larsen v the Hawaiian Kingdom case, Sai has made the education of Hawaii’s people his top priority.

Now, inspired by stories like the one of the HSTA in Boston, Sai feels affirmed that “it’s time to go fact-finding.”

“I think the time is right. Let’s enter into an agreement with Lance Larsen, go fact-finding,” Sai said, adding that during the 2001 proceedings before the the Permanent Court of Arbitration, the tribunal “didn’t say you can create the fact-finding within 20 years. It said all it needs is an agreement.”

Sai said two of the arbitrators are now sitting judges on the International Court of Justice.

“So, what we’re going to do is convene the original arbitrators who made the statement to be that Commission of Inquiry,” Sai said. “Because I found out that sitting judges on the International Court of Justice can also serve as arbitrators and commissioners at the permanent Court of Arbitration.”

Commissions of inquiry under the auspices of the Permanent Court serve in a similar capacity as grand juries, Sai told the audience. Commissions of Inquiry not only review sets of facts, but also assign responsibilities regarding these facts. That could be civil liability or criminal liability in international law, Sai said.

To date there have only been five International Commission’s of Inquiry, Sai said. The first was Great Britain and Russia in 1905. The most recent was Great Britain and Denmark in 1962.

“This is not… a happy time, but this is a serious time,” Sai said. “Now, what’s important here is, this agreement which will form three commissioners under the Hague Convention… they will answer the first question. First, what is the function and role of the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom in accordance with the basic norm and framework of international humanitarian law?”

Humanitarian law is the law of occupation and laws of war, Sai said. “Before you can address what is the role of the Hawaiian government during occupation, you have to do that in the light of what happened since 1893. You have to address what the United States did or didn’t do that got us into this situation of possible culpability of the Hawaiian government toward one of its Nationals. Is it our fault that everybody’s brainwashed?

Who’s responsible for that?”

Before the commission can answer that question, they have to “address over a hundred years of non-compliance to humanitarian law,” Sai said. “That’s how it works. Then, in light of all this… what do we do? Are we liable?”

Sai says the commission will also ask, “what are the duties and obligations of the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom toward Lance Larson and – by extension – toward all Hawaiian subjects residing in Hawaii, and abroad?”

“What do we do about Lance Larson? Do we sign a reparation where we now have to pay him?” Sai asked. “Do we report the crimes to the International Criminal Court for prosecution? Where do we go?”

“Let them tell us,” Sai said. “They have the authority. We’re in the procedures. So, I don’t know what they’re going to say. I don’t. Just as I didn’t know what they would say during the proceedings of arbitration. I just know I have to take every step to protect the Hawaiian government. Because we’re in it. We’re now being put to that test.”

Sai added that once the Commission has been convened, they are going to make an important recommendation. “We’re gonna have the hearings in Hawaii,” Sai said, to a round of applause.

“I mean, this is not a political stunt. This is procedural,” Sai said. “Because… back in the year 2000, we entertained whether or not the tribunal could have their hearings in Hawaii. That was under consideration. And, after complete review, we said ‘no, there is confusion at home’. Now, I think our people are ready. They have the knowledge, they have the understanding.”

Sai again pointed to the recent HSTA victory in getting their “illegal occupation” proposal passed at the NEA meeting in Boston.

“Can you now understand,” Sai asked the crowd, “the Commission of Inquiry will probably be looking into these very issues.”

(BIVN) – As a part of the two day La Hoʻihoʻi ʻEa educational seminar held at the Boys & Girls Club in Hilo, Dr. Wille Kauai gives a talk, Understanding the impact of denationalization in the Hawaiian Kingdom.

The presenter delved into the history and issues surrounding nationality, race, and citizenship in the context of the prolonged occupation of Hawaii by the Untied States.

(BIVN) – As a part of the two day La Hoʻihoʻi ʻEa educational seminar held at the Boys & Girls Club in Hilo, Dr. Keanu Sai gives a presentation, The current role of the Acting Hawaiian Kingdom government in the prolonged occupation.

Sai talks about how there is a state of war between the United States and the Hawaiian Kingdom, his efforts as lead agent for the Kingdom at the Permanent Court of Arbitration, and the ongoing education of Lāhui.