Smithsonian Institute—Hawaiian Kingdom Episode 2: Hawaiian Diplomacy

3

On MSNBC’s Meet the Press, Dr. Michael Osterholm, Director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, said in an interview with host Chuck Todd, “What we have to do is figure out how not just to die with the virus, but also how to live with it. And we’re not having that discussion.”

Instead, the discussion around the world has been focused on a vaccine, which some have said could be done within 12 to 18 months from now. But Dr. Rick Bright, former director of the U.S. government’s Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, told members of Congress, “It’s critical to note that when we say 12 to 18 months, that doesn’t mean for an FDA-approved vaccine, it means to have sufficient data and information on the safety and immunogenicity, if not efficacy, to be able to use on an emergency basis, and that is the consideration we have in mind when we talk about an accelerated timeline.”

World Health Organization’s emergencies expert, Dr. Mike Ryan, said on an online briefing, “It is important to put this on the table: this virus may become just another endemic virus in our communities, and this virus may never go away.”

Even after flattening the curve of infections throughout the islands, health experts are expecting a second wave. Unless preventive measures are taken to effectively control the entry of the virus from foreign countries, which includes the United States, a second wave could be devastating on the health and well-being of Hawai‘i’s people and the economy.

A New Legal Reality for Hawai‘i Has Emerged

Before the pandemic crisis reached the islands, undeniable facts had begun to reveal that Hawai‘i has been under a prolonged American occupation since January 17, 1893 after United States troops invaded the Hawaiian Kingdom and overthrew its government.

People have been under the false impression that since Queen Lili‘uokalani was overthrown so was the country. International law distinguishes between the government of the country and the country itself. It was the Queen as head of the government that was illegally overthrown by the United States and not the country the Hawaiian Kingdom.

This would be analogous to the United States military defeat of Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi government in Baghdad on April 9, 2003. The overthrow of the government did not affect the status of Iraq as a country, but it did bring the United States, as an occupying power, under the international law of occupation.

For over a century, the United States violated the international law of occupation in the Hawaiian Kingdom which led to the commission of war crimes and human rights violations committed with impunity.

International awareness of Hawai‘i’s occupation was accelerated due to the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom arbitral proceedings held at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague from 1999-2001 that was based on the American occupation and the unlawful imposition of American laws within Hawaiian territory. Of significance, the Permanent Court acknowledged the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State, which is another word for country, and the Hawaiian Council of Regency as its interim government.

On the subject of Hawai‘i’s occupation and the commission of war crimes, Professor William Schabas, recognized expert in international criminal law, wrote: “In addition to crimes listed in applicable treaties, war crimes are also recognized under customary international law. Customary international law applies generally to States regardless of whether they have ratified relevant treaties. The customary law of war crimes is thus applicable to the situation of Hawai‘i.” Schabas also stated, “Statutory limitation of war crimes is prohibited by customary law.”

Also commenting on the prolonged occupation, international human rights expert, Professor Federico Lenzerini, stated, “among the rights which may be supposed of having been violated by the United States as a result of the occupation of the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom particular attention should be devoted to those inherently connected to the violations of international humanitarian law determined by the occupation. These violations…would first of all need to be treated as war crimes, which are primarily to be considered under the lens of international criminal law.”

To read Professors Schabas’ and Lenzerini’s full opinions on war crimes and human rights violations and the role of the Hawaiian Royal Commission of Inquiry download the free eBook The Royal Commission of Inquiry: Investigating War Crimes and Human Rights Violations Committed in the Hawaiian Kingdom.

What effect does this new legal reality have in dealing with COVID-19? The simple answer is that international law broadens the scope as to how to deal with the virus that did not exist before. In particular, it provides for legal authority to close the borders.

Here is a relevant Hawaiian proverb. “I ke au i hala ka lamaku o ke ala i ke kupukupu.” (The past is the beacon that will guide us into the future)

Why the International Law of Occupation Applies to Hawai‘i

The silver lining in the international law of occupation takes the position that Hawai‘i, which is known internationally as the Hawaiian Kingdom, remains its own separate country despite over a century of an illegal occupation by the United States. As an occupied country, decisions are not made by inept leadership at the United States federal level but rather by the rules of international humanitarian law, which includes the law of occupation, by those who are in effective control of Hawaiian territory.

There are two important tenets of the law of occupation. First, is the duty of the occupying power or its proxy to administer the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and, second, the protection of the health and well-being of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s inhabitants that are both Hawaiian subjects and resident aliens. Occupations by foreign countries are regulated by the 1907 Hague Regulations and the 1949 Fourth Geneva Convention.

However, before the Hague Regulations and the Geneva Convention can be applied over the Hawaiian Islands, the occupying power or its proxy has to be in effective control of the territory. For without effective control, there would be no enforcement mechanism for ensuring effective governance. Article 42 of the Hague Regulations states that “Territory is considered occupied when it is actually placed under the authority of the hostile army.”

Article 42 has three requisite elements before the duty to administer the laws of the occupied country becomes obligatory upon the occupying power or its proxy. First, there must be the presence of a foreign country’s forces; second, the exercise of authority over the occupied territory by the foreign country or its proxy; and, third, the non-consent by the occupied country’s government.

In March of 1893, President Grover Cleveland initiated a presidential investigation into the overthrow of the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom on January 17, 1893 and the creation of the provisional government. After completing the investigation, he notified the Congress of his findings on December 18.

In his message to the Congress, he stated, that a protest “signed by the Queen and her ministers at the time she made way for the provisional government, which explicitly stated that she yielded to the superior force of the United States, whose Minister had caused United States troops to be landed at Honolulu and declared that he would support such provisional government.”

As to the status of the provisional government, the President stated, “I believe that a candid and thorough examination of the facts will force the conviction that the provisional government owes its existence to an armed invasion by the United States. Fair-minded people with the evidence before them will hardly claim that the Hawaiian Government was overthrown by the people of the islands or that the provisional government had ever existed with their consent.”

The President also concluded, “In this state of things if the Queen could have dealt with the insurgents alone her course would have been plain and the result unmistakable. But the United States had allied itself with her enemies.”

The President entered into an agreement of restoration with the Queen as head of the Hawaiian government but political wrangling in the Congress prevented the restoration because proponents in the Congress wanted Hawai‘i as a military outpost.

The only change in the Hawaiian governmental infrastructure was the Queen and her Cabinet that was replaced by 18 insurgents calling themselves the Executive and Advisory Councils. Everyone else in the governing body remained but were coerced into signing oaths of allegiance to the regime while United States military forces were present.

A colloquial term for the illegal overthrow would be a “car-jacking.” All that was changed was the driver and not the car.

Five years later on July 7, 1898, during the Spanish-American War, the Congress passed a law purporting to have annexed the Hawaiian Islands. The United States took control of their insurgents, who were then calling themselves the Republic of Hawai‘i, in 1900 when Congress renamed them as the Territory of Hawai‘i. In 1959, the Congress renamed the Territory to the State of Hawai‘i. What changed was merely the names of purported governments and not the legality of the situation.

A basic principle of United States law is that legislation has no legal effect outside of its territory. In other words, the Congress could no more annex the Hawaiian Islands in 1898 by enacting a law than it could no more annex Canada today by enacting a law. Acquisition of foreign territory is a matter of international law and is done by a treaty. There is no treaty of cession between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States.

In 1936, the United States Supreme Court, in United States v. Curtiss Wright Export Corp, made clear, “Neither the Constitution nor the laws passed in pursuance of it have any force in foreign territory unless in respect of our own citizens, and operation of the nation in such territory must be governed by treaties, international understandings and compacts, and the principles of international law.”

Mindful of the territorial limits of American legislation, the Office of Legal Counsel for the U.S. Department of Justice, in 1988, concluded “it is therefore unclear which constitutional power Congress exercised when it acquired Hawaii by joint resolution.” If it was unclear how the Congress could annex a foreign country, it would be equally unclear how the Congress could have created the Territory of Hawai‘i in 1900 or the State of Hawai‘i in 1959 in a foreign country.

Instead of a treaty, the United States embarked on an effective policy of denationalization through Americanization in the schools throughout the kingdom. It was here that young school children were brainwashed into believing that the Hawaiian Islands had become a part of the United States and that English was the new language. Within three generations, Hawaiian national consciousness was replaced with American national consciousness and the greatest travesty of international law would go unnoticed for over a century.

For a comprehensive explanation of the overthrow and the subsequent American occupation visit the National Education Association’s website neaToday that published three articles on the subject. The “NEA’s 3 million members work at every level of education—from pre-school to university graduate programs. NEA has affiliate organizations in every state and in more than 14,000 communities across the United States.”

How Does the Law of Occupation Apply to COVID-19 in Hawai‘i

The United States presence in the Islands is illegal and its current form of governance has been unlawfully imposed for over a century. But to apply international laws, there needs to be an understanding of the current system, albeit unlawful, in order to understand how to transform the State of Hawai‘i into something recognizable under international law in order begin to comply with the laws of occupation so that administration of the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom can begin.

The United States is a multitiered governing system called a federation. At the top is the national or federal government, headed by a president, and below it are the various States that are headed by governors. In the case of the State of Hawai‘i, there are the four County governments below the State who are headed by mayors.

As a proxy of the United States, only the State of Hawai‘i and its Counties, and not the federal government, are in effective control of Hawaiian territory. By being in effective control, the State of Hawai‘i and the Counties meets the requirement of effectiveness under Article 42 of the Hague Regulations.

Under Article 43 of the Hague Regulations and Article 64 of the Geneva Convention, the State of Hawai‘i and its Counties are obligated to administer the “laws in force in the country,” which in this case would be the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom as it stood before the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Government on January 17, 1893.

With particular focus on infectious diseases, Article 54 of the Geneva Convention states that the occupying power or its proxy has the obligation to ensure and maintain, “public health and hygiene in the occupied territory, with particular reference to the adoption and application of the prophylactic and preventative measures necessary to combat the spread of contagious diseases and epidemics.”

Professor Marco Sassòli, an expert on the law of occupation, explains, “The expression ‘laws in force in the country’ in Article 43 refers not only to laws in the strict sense of the word, but also to the constitution, decrees, ordinances, court precedents (especially in territories of common law tradition), as well as administrative regulations and executive orders.” Administrative regulations that would specifically apply to the pandemic would include those of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s Board of Health and the Board of Immigration.

As smallpox and COVID-19 are both viruses, there is much to learn from the Hawaiian Kingdom’s past. Like COVID-19, the smallpox virus would spread from person to person by inhaling respiratory droplets or contact with infected persons or material. Smallpox was not eradicated until 1977.

In the nineteenth century, inoculation was the form of a vaccine, but this was a preventive measure. Also, inoculation was not full proof but it was all the nineteenth century had at the time. Once a person became infected there was no medical treatment and all that could be done was to provide hospital care until the virus ran its course. Once an outbreak occurred, quarantine was the only effective response in order to contain the virus. According to the World Health Organization, smallpox had “an incubation period of between 7 and 17 days after exposure and only becomes infectious once the fever develops,” and had a 30% death rate.

Living with Infectious Viruses in the Hawaiian Kingdom

The 1853 smallpox epidemic in the Hawaiian Kingdom was the most devastating health disaster in Hawai‘i’s history with over 5,000 deaths, which meant roughly 16,500 people were infected. The infections and death were predominantly in the city of Honolulu.

Hawaiian historian, Samuel Kamakau, who witnessed the ravage, wrote, “From the last week in June until September the disease raged in Honolulu. The dead fell like dried kukui twigs tossed down by the wind. Day by day from morning till night horse-drawn carts went about from street to street of the town, and the dead were stacked up like a load of wood, some in coffins, but most of them just piled in, wrapped in cloth with heads and legs sticking out.”

The government reported, “No new cases of smallpox has been reported. Those already existing are doing well. The health of the city is otherwise generally good.” After two-months the epidemic passed and Honolulu was virus free.

This was a test for the newly created Smallpox Commission that was established by statute on May 16, 1853. The statute’s preamble stated, “Whereas, the Small-Pox is believed to exist in this Kingdom, and humanity and a just regard to life require that all who are affected with that disease should receive strict care and attention, and whereas it is desirable that the disease shall not extend through the Islands.” Following the outbreak, an Act was passed by the legislature on August 10, 1854 making “compulsory the practice of vaccination throughout the Hawaiian Islands.” The Board of Health eventually assumed complete control in response to future smallpox outbreaks.

After the King, in Privy Council, in 1869 concluded that smallpox was endemic to the west coast of the United States and posed a direct threat to the health and well-being of Hawai‘i’s people, Mokuakulikuli—known today as Sand Island, was designated as the Quarantine Ground. The Hawaiian Gazette reported, “Altogether, about ninety persons can be comfortably accommodated at the quarantine buildings.”

Vaccinations in the nineteenth century were not full proof and another outbreak of smallpox hit Honolulu in 1881 that lasted just over five months. 282 people lost their lives.

There were hard lessons learned from the second outbreak that eventually culminated in the Board of Health’s adoption of a more comprehensive and authoritative quarantine regulations in 1891. The regulations focused on incoming passenger and merchant ships arriving from foreign ports.

Under these quarantine regulations, full authority and centralized control was vested in the Board of Health to make on the spot decisions that had the backing of the Hawaiian government through enforcement. The regulations were driven by medical experts and not politicians.

The regulations also provided who was responsible for the costs of the quarantine, which would not be incurred by the Hawaiian government. If payment was refused, the ship and/or assets were seized and liquidated to pay for the costs the government incurred.

1891 Quarantine Regulations

Although these regulations were applied to arriving ships throughout the kingdom, they are applicable today to airplanes arriving throughout the various airports as well.

If the United States or its proxy the State of Hawai‘i was complying with the international law of occupation by administering the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom, COVID-19 would have been detected much sooner and quarantine measures would have taken effect followed by a lockdown of the borders to prevent foreign travelers from re-introducing the virus.

Hawaiian Bureau of Immigration and the Authority to Deny Entry

The legislature in 1864 established a Bureau of Immigration within the Ministry of the Interior. Its purpose was “superintending the importation of foreign laborers, and the introduction of immigrants.” The Bureau came under the control of the Minister of the Interior who was “assisted by a committee of five members of the Privy Council of State, to be appointed by His Majesty the King for that purpose.”

On January 14, 1880, the Bureau enacted an ordinance regulating immigration. In particular, Section 7 of the ordinance provided, “Immigrants not desiring to make engagements for labor shall, before leaving the depot, furnish to the President of the Board of Immigration satisfactory evidence that they will not become vagrants or a charge on the community for their support.”

Section 7 was the basis for the denial of a petition for writ of habeas corpus to the Hawaiian Kingdom Supreme Court by two passengers that completed quarantine for smallpox but were still detained by the Minister of the Interior because they did not satisfy section 7 of the regulations of the Board of Immigration.

Before the second outbreak of smallpox in Honolulu, the steamship Septima arrived in Honolulu from China on February 13, 1880. It was determined by the Board of Health that the virus existed amongst the passengers and they were removed to Sand Island for quarantine.

After they were cleared of smallpox by the Board of Health, authority was then passed over to the Board of Immigration. They were further detained by the Minister of the Interior until each of the passengers provided evidence that “they will not become vagrants or a charge on the community for their support.”

Two of the passengers from China refused to agree with section 7 of the regulations and claimed that the ordinance, itself, was unlawful because it was not a law passed by the legislature. In the Matter of Chow Bick Git and Wong Kuen Leong, the Hawaiian Kingdom Supreme Court, in 1881, not only denied the petition by upholding the Board of Immigration’s ordinance as constitutional, it also addressed the authority of the Hawaiian government to deny entry of foreigners.

After the Court cited Vattel’s Law of Nations and the passenger cases before the United States Supreme Court on a State’s authority to deny entry into its territory by foreigners, Associate Justice Albert F. Judd provided a separate opinion in agreement with the Chief Justice. He further stated:

“the State has a right to impose such terms and conditions precedent to the entry of foreigners within its borders as in its opinion are essential to its welfare, peace and good government. I see no reason why a sovereign State may not prescribe these terms, even in the absence of municipal law declaring what they shall be. The State may say to those who seek to become residents within its territory, ‘We will admit you, providing you accede to these terms which we deem to be reasonable and necessary.’”

Living with COVID-19 in the Hawaiian Islands

The American response of “flattening the curve” is an American policy to prevent its hospitals from being overwhelmed until a vaccine can be found. A full proof smallpox vaccine did not exist until the twentieth century where the last natural outbreak of smallpox in the United States occurred in 1949. In the meantime, the Hawaiian Kingdom had to live with the virus and its defense was hospital care and quarantine measures.

Instead of “flattening the curve,” Hawai‘i, like in the nineteenth century, should focus on “eliminating the virus” throughout the Islands by closing the borders until the virus completes its infectious incubation period. During this time, test, tracing and quarantine continues.

In an interview on KITV Island News, Dr. Bruce Anderson from the State of Hawai‘i Board of Health acknowledged that countries that have good quarantine programs and who have the ability to control their borders are relying largely on quarantine and not testing.

New Zealand, like Hawai‘i, is an island country that can control their borders much more effectively than landlocked States of the United States. The ocean now becomes a moat for the defense of a castle.

Advised by epidemiologists, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern announced on March 14 that almost everyone coming into New Zealand would have to self-quarantine for 14 days. It was one of the earliest moves to isolate a country in the world. A total lockdown for the country followed on March 26 with a moratorium on domestic travel.

The government eventually closed its borders except for “New Zealand citizens, permanent residents and residents with valid travel conditions.” It later allowed transiting travelers to certain countries but they were required to remain in the airport and if the transit flight would be more than 24 hours they cannot enter New Zealand.

The Prime Minister explained, “We’re going hard and we’re going early. We only have 102 cases, but so did Italy once.” The goal of the New Zealand government, with the closing of the borders, was to not have any more community transmissions.

By late April, infections dropped to seven, which motivated the government to ease on its domestic lockdown. On April 21, the Prime Minister told Radio New Zealand, “We can say with confidence that we do not have community transmission in New Zealand. The trick now is to maintain that.”

The Prime Minister, being advised by epidemiologists, said she was not seeking to eradicate the virus from the country but rather have “zero tolerance for cases.” Her advisors stated their approach would be similar to a response to measles with swift response of medical treatment for those infected, contact tracing and isolation. This is how the Hawaiian Kingdom lived with infectious viruses in the nineteenth century that arrived into the country, swiftly moving to identify infected persons, provide care and quarantine.

According to New Zealand’s Ministry of Health, “effective border control becomes even more important than before. As people within New Zealand are able to travel and mix more freely, the ability of COVID-19 to spread potentially increases. So we must keep it out at the border. We already know the border is one of the main sources of new cases of COVID-19.”

Hawai‘i should follow New Zealand’s lead but it first needs to comply with the law occupation as a governing body recognizable under international law. Once COVID-19 is eliminated in the islands and the borders remain closed under the regulations of the Hawaiian Board of Immigration, interisland flights can resume and Hawai‘i can get back to pre-pandemic life with some adjustments just as the country did after the 1881 breakout of smallpox.

No Choice for the State of Hawai‘i to Comply with the Law of Occupation

Since 1898, the United States, through its proxy the Territory of Hawai‘i since 1900 and now the State of Hawai‘i since 1959, has been illegally imposing its municipal laws throughout the Hawaiian Islands. Customary international law refers to this unlawful imposition of one country’s laws into the territory of an occupied country as “usurpation of sovereignty,” which is a war crime.

“In the situation of Hawai‘i, the usurpation of sovereignty would appear to have been total since the beginning of the twentieth century,” says Professor Schabas. He argues “that usurpation of sovereignty is a continuous offense, committed as long as the usurpation of sovereignty persists.”

Professor Schabas states that the criminal act, or actus reus, of usurpation of sovereignty “would consist of the imposition of legislation or administrative measures by the occupying power that go beyond those required by what is necessary for military purposes of the occupation.” In other words, if a person or persons imposed American legislative or administrative measures in Hawai‘i you committed the war crime.

The volitional element, or criminal intent, of usurpation of sovereignty,” according to Professor Schabas, is that the “perpetrator was aware of factual circumstances that established the existence of the armed conflict and subsequent occupation.” What is important is not just the criminal act but was there criminal intent to commit the criminal act.

If there was no awareness of the American occupation, there was no intent for prosecution purposes. In other words, was Governor David Ige aware of Hawai‘i’s occupation?

On three separate occasions in June of 2015, Governor Ige’s Chief of Staff Mike McCartney met with Dr. Keanu Sai who was at the time the attorney-in-fact for two war crime victims who were in communication with the Swiss Attorney General’s office for war crimes. Dr. Sai conveyed to McCartney that his clients were willing to forgo filing war crime complaints if the Governor would take corrective measures to address the circumstances of the two victims.

The following month on July 2, Dr. Sai provided McCartney a Report that covered what was discussed in the three meetings and a proposed remedy in line with international law and the relevant rules of the States of Hawai‘i. The opening statement in Dr. Sai’s cover letter stated:

“Enclosed please find a report I authored, titled Military Government: Transformation of the State of Hawai‘i, for your consideration. As you know after we met on three previous occasions, this is a serious matter with profound political and economic consequences. After our last meeting I scoured through the laws and customs of war and international humanitarian law, and I discovered that the State of Hawai‘i is fully authorized to declare itself as a Military Government in accordance with provisions in the State Constitution and the laws and customs of war during occupation.”

McCartney, for whatever reason, did not follow up with Dr. Sai. What is not clear is why there was no follow up. What is unquestionably clear, for the purpose of criminal culpability under international law, is that Governor Ige’s administration was “aware of factual circumstances that established the existence of the armed conflict and subsequent occupation” for the past five years.

Governor Ige was also made aware of Hawai‘i’s occupation by Maui County Council member Tamara Paltin who was communicating with University of Hawai‘i President David Lassner regarding the proposed building of the thirty-meter telescope on the summit of Mauna Kea. Governor Ige and the Attorney General were carbon copied in the communications.

How the State of Hawai‘i Will Comply with the Law of Occupation

In decision theory, a negative-sum game is where everyone loses. Any decision from a loss can only have the effect of a loss—a lose-lose situation. The State of Hawai‘i is presently operating from a position of no lawful authority, and everything that it has done or that it will do is unlawful. There can be no fruit from a poisonous tree. The rapidly growing knowledge and awareness of the prolonged occupation of Hawai‘i has the effect of causing the State of Hawai‘i to speedily descend and crash.

The State of Hawai‘i has found itself in a mammoth negative-sum game. In order to stave off the inevitable, the Council of Regency and the State of Hawai‘i must cooperate so that positive-sums are realized. The law of occupation provides the legal basis for the State of Hawai‘i to realize positive-sums.

Critical to the administration of Hawaiian law is the establishment of a Military government recognizable under international law, which is “defined as the supreme authority exercised by an armed occupying force over the lands, properties, and inhabitants of an enemy, allied, or domestic territory.”

The establishment of a Military government is not limited to the U.S. military, but to a proxy of the Occupying power that is in effective control of occupied territory. Section 4(b), U.S. Army Field Manual FM 27-5, provides that an occupying Power “has the duty of establishing [Military government] when the government of such territory is absent or unable to function properly.”

What distinguishes the U.S. military stationed in the Hawaiian Islands from the State of Hawai‘i is that the State of Hawai‘i, as a proxy of the United States, is in effective control of the majority of Hawaiian territory. U.S. military sites number 118 that span 230,929 acres of the Hawaiian Islands, which is only 20% of the total acreage of Hawaiian territory. The balance of Hawaiian territory is controlled by the State of Hawai‘i and its Counties.

As a proxy for the Occupying power, the State of Hawai‘i has no choice but to establish itself as a Military government, which is allowable under the laws of occupation, to provisionally serve as the administrator of the “laws in force in the country.”

According U.S. Army FM 27-10, “Military government is exercised when an armed force has occupied such territory, whether by force or agreement, and has substituted its authority for that of the sovereign or previous government. The right of control passes to the occupying force limited only by the rules of international law and established customs of war.”

The proclamation for the establishment of a Military government would be done in like fashion to the declaration of martial law for the Hawaiian Islands from December 7, 1941 to April 4, 1943. Governor Joseph Poindexter and Lieutenant General Walter Short relied on section 67 of the 1900 Territorial Act as the basis to establish a Military government. The Governor appointed General Short as the Military Governor in charge of the Military government.

The 1941 proclamation, however, required the prior approval of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, since the Governor of the Territory of Hawai‘i was a Presidential appointee.

When the Territory was transformed to the State of Hawai‘i in 1959, section 67 was replaced by Article V, section 5 of the State of Hawai’i Constitution, which gives the Governor full and complete authorization to declare the establishment of a Military government without the prior approval of the President.

In order to transform the State of Hawai‘i into a Military government, the Governor will need to decree, by proclamation, the establishment of a Military government in accordance with Article V, section 5 of the State of Hawai’i Constitution, which will bring it in conformity with section 5(3) of FM 27-5 that states the purpose of a Military government is to “fulfill the obligation of the occupying force under international law.”

Additionally, the proclamation should also decree that all State of Hawai‘i judicial and executive officers and employees remain in operation with the exception of the legislative bodies to include the Legislature and County Councils. This reasoning is because “since supreme legislative power is vested in the military governor, existing legislative bodies will usually be suspended.”

Although the Council of Regency recognized “the State of Hawai‘i and its Counties, for international law purposes, as the administration of the Occupying Power whose duties and obligations are enumerated in the 1907 Hague Convention, IV, the 1949 Geneva Convention, IV, and international humanitarian law,” by proclamation on June 3, 2019, it failed to transform itself into a Military government.

A condition of the recognition, as stated in the proclamation, was “that the State of Hawai‘i and its Counties shall preserve the sovereign rights of the Hawaiian Kingdom government, and to protect the local population from exploitation of their persons and property, both real and personal, as well as their civil and political rights under Hawaiian Kingdom law.”

The State of Hawai‘i and its Counties have not preserved the sovereign rights of the Hawaiian Kingdom and has continued to exploit the local population by imposing the legislative and administrative measures of the United States. Once the State of Hawai‘i transforms itself into a Military government, the recognition takes effect.

Until such time, members of the State of Hawai‘i and its Counties could find themselves under investigation for war crimes by the Royal Commission of Inquiry that was established by the Council of Regency on April 17, 2019.

The mandate of the Royal Commission is “to investigate the consequences of the United States’ belligerent occupation, including with regard to international law, humanitarian law and human rights, and the allegations of war crimes committed in that context. The geographical scope and time span of the investigation will be sufficiently broad and be determined by the head of the Royal Commission.”

The Royal Commission recently published an eBook Investigating War Crimes and Human Rights Violations Committed in the Hawaiian Kingdom, as well as its first preliminary report The Material Elements of War Crimes and Ascertaining the Mens Rea.

Bringing Hawaiian Kingdom Law Up To Date

Because United States laws, to include the current federal laws and laws of the State of Hawai‘i and its Counties, are unlawful, the only valid laws in Hawai‘i are the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom, which include “the constitution, decrees, ordinances, court precedents, as well as administrative regulations and executive orders.”

In order to bring these laws up to date, the Council of Regency proclaimed on October 10, 2014, that “all laws that have emanated from an unlawful legislature since the insurrection began on July 6, 1887 to the present, to include United States legislation, shall be the provisional laws of the Realm subject to ratification by the Legislative Assembly of the Hawaiian Kingdom once assembled, with the express proviso that these provisional laws do not run contrary to the express, reason and spirit of the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom prior to July 6, 1887, the international laws of occupation and international humanitarian law, and if it be the case they shall be regarded as invalid and void.”

Once the Military government has been proclaimed, the Governor should follow up with a supplemental proclamation announcing the Council of Regency’s proclamation of provisional laws.

Reality Check

These are serious times in Hawai‘i for those in power. Since 1893, this power has been unchecked and unbridled but now under the international law of occupation and international criminal law the rule of law has now taken its place front and center.

The decision to transform the State of Hawai‘i into a Military government is not a political decision. It is a decision made in light of indisputable facts, international law, and awareness of the American occupation of a sovereign State.

As Professor Schabas stated, which is also acknowledged by the International Criminal Court, there “is no requirement for a legal evaluation by the perpetrator” of Hawai‘i’s occupation. Rather, there “is only a requirement for the awareness of the factual circumstances that established the existence” of Hawai‘i’s occupation.

Without evidence that denies the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom, international criminal law is a vice grip on individuals where the potential for the prosecution of war crimes can last up to a person’s elderly years. As Professor Schabas stated, “human longevity means that the inquiry into the perpetration of war crimes becomes abstract after about 80 years, bearing in mind the age of criminal responsibility.”

In response to the prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom by the United States since 1893, and the commission of war crimes and human rights violations that continue to take place with impunity, the Royal Commission of Inquiry was established by the Council of Regency on April 17, 2019. The Council of Regency represented the Hawaiian Kingdom at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, PCA case no. 1999-01, from 1999-2001. The Royal Commission’s mandate is to “ensure a full and thorough investigation into the violations of international humanitarian law and human rights within the territorial jurisdiction of the Hawaiian Kingdom.”

Dr. David Keanu Sai was appointed as Head of the Royal Commission and he has commissioned recognized experts in various fields of international law who are the authors of chapters 3, 4 and 5 of this publication. These experts include Professor Matthew Craven, University of London, SOAS; Professor William Schabas, Middlesex University London; and Professor Federico Lenzerini, University of Siena.

Its first 378 page publication, Royal Commission of Inquiry: Investigating War Crimes and Human Rights Violations in the Hawaiian Kingdom, provides information on the Royal Commission of Inquiry, Hawaiian Constitutional Governance, the United States Belligerent Occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom, the Continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State, Elements of War Crimes committed in the Hawaiian Kingdom, and Human Rights violations and Self-determination. The Royal Commission will provide periodic reports of its investigation of war crimes committed by individual(s) that meet the constituent elements of mens rea and actus reus, and human rights violations.

There is no statute of limitation for war crimes but it is customary for individual(s) to be prosecuted for the commission of war crimes up to 80 years after the alleged war crime was committed given the life expectancy of individuals. As a matter of customary international law, States are under an obligation to prosecute individuals for the commission of war crimes committed outside of its territory or to extradite them for prosecution by other States or international courts should they enter their territory.

**The book is free of charge and authorization is given, in accordance with its copyright under Hawaiian law, to print in soft-cover or hard-cover so long as the content of the book is not altered or edited.

Posted on the National Lawyers Guild’s website on January 13, 2020.

The National Lawyers Guild (NLG), the oldest and largest progressive bar association in the United States, calls upon the United States to immediately begin to comply with international humanitarian law in its prolonged and illegal occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom since 1893. As the longest running belligerent occupation of a foreign country in the history of international relations, the United States has been in violation of international law for over a century.

THE HAWAIIAN KINGDOM AS A SOVEREIGN AND INDEPENDENT STATE

On November 28, 1843, Great Britain and France jointly recognized the Hawaiian Kingdom as a sovereign and independent State, which was followed by formal recognition by the United States on July 6, 1844. By 1893, the Hawaiian Kingdom maintained over 90 legations (embassies) and consulates throughout the world, to include a legation in Washington, D.C., and consulates in the cities of New York, San Francisco, Philadelphia, San Diego, Boston, Portland, Port Townsend and Seattle. The United States also maintained a legation and consulate in Honolulu.

The Hawaiian Kingdom also held treaties with the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Belgium, Bremen, Denmark, France, Germany, Great Britain, Hamburg, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Russia, Samoa, Spain, Switzerland, the unified Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway, and the United States. It was also a member of the Universal Postal Union.

As a constitutional monarchy, the kingdom provided universal healthcare for the aboriginal Hawaiian population since 1859 with the establishment of Queen’s Hospital, and it became the fifth country in the world to provide compulsory education for all youth in 1841. This predated compulsory education in the United States by seventy-seven years and its literacy rate was universal and second to Scotland. Also, between 1880 and 1887, a study abroad program was launched where 18 young Hawaiian subjects attended schools in the United States, Great Britain, which included Scotland, Italy, Japan and China where they studied engineering, law, foreign language, medicine, military science, engraving, sculpture, and music.

PRESIDENT GROVER CLEVELAND’S MESSAGE TO THE CONGRESS IN DECEMBER 18, 1893

After completing an investigation into the United States role in the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government on January 17, 1893, President Cleveland apprised the Congress of his findings and conclusions. In his message to the Congress, he stated, “And so it happened that on the 16th day of January, 1893, between four and five o’clock in the afternoon, a detachment of marines from the United States steamer Boston, with two pieces of artillery, landed at Honolulu. The men, upwards of 160 in all, were supplied with haversacks and canteens, and were accompanied by a hospital corps with stretchers and medical supplies. This military demonstration upon the soil of Honolulu was of itself an act of war.” He concluded, that “the military occupation of Honolulu by the United States on the day mentioned was wholly without justification, either as an occupation by consent or as an occupation necessitated by dangers threatening American life and property.”

This invasion coerced Queen Lili‘uokalani, executive monarch of the Hawaiian Kingdom, to conditionally surrender to the superior power of the United States military, where she stated, “Now, to avoid any collision of armed forces and perhaps the loss of life, I do, under this protest, and impelled by said force, yield my authority until such time as the Government of the United States shall, upon the facts being presented to it, undo the action of its representatives and reinstate me in the authority which I claim as the constitutional sovereign of the Hawaiian Islands.” The President acknowledged, that by “an act of war…the Government of…friendly and confiding people has been overthrown.”

Through executive mediation between the Queen and the new U.S. Minister to the Hawaiian Islands, Albert Willis, that lasted from November 13, 1893 through December 18, 1893, an agreement of peace was reached. According to the executive agreement, by exchange of notes, the President committed to restoring the Queen as the constitutional sovereign, and the Queen agreed, after being restored, to grant a full pardon to the insurgents. Political wrangling in the Congress, however, blocked President Cleveland from carrying out his obligation of restoration of the Queen.

LIMITATION OF THE UNITED STATES CONSTITUTION AND LAWS

Five years later, at the height of the Spanish-American War, President Cleveland’s successor, William McKinley, signed a congressional joint resolution of annexation on July 7, 1898, unilaterally seizing the Hawaiian Islands for military purposes. In the Lotus case, the Permanent Court of International Justice stated that “the first and foremost restriction imposed by international law upon a State is that…it may not exercise its power in any form in the territory of another State.”

This rule of international law was acknowledged by the Supreme Court in United States v. Curtiss-Wright, Corp. (1936), when the court stated, “Neither the Constitution nor the laws passed in pursuance of it have any force in foreign territory unless in respect of our own citizens, and operations of the nation in such territory must be governed by treaties, international understandings and compacts, and the principles of international law.” In 1988, the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel concluded, it is “unclear which constitutional power Congress exercised when it acquired Hawaii by joint resolution.”

Under international law, “a disguised annexation aimed at destroying the independence of the occupied State, represents a clear violation of the rule preserving the continuity of the occupied State (Marek, Identity and Continuity of States in Public International Law, 2nd ed. 110 (1968)).”

Despite the limitations of United States legislation, the Congress went ahead and enacted the Territorial Act (1900) changing the name of the governmental infrastructure to the Territory of Hawai‘i. Fifty-nine years later, the Congress changed the name of the Territory of Hawai‘i to the State of Hawai‘i in 1959 under the Statehood Act. The governmental infrastructure of the Hawaiian Kingdom continued as the governmental infrastructure of the State of Hawai‘i.

According to Professor Matthew Craven in his 2002 legal opinion for the Hawaiian Council of Regency concluded, “That authority exercised by [the United States] over Hawai‘i is not one of sovereignty i.e. that the [United States] has no legally protected ‘right’ to exercise that control and that it has no original claim to the territory of Hawai‘i or right to obedience on the part of the Hawaiian population. Furthermore, the extension of [United States] laws to Hawai‘i, apart from those that may be justified by reference to the law of (belligerent) occupation would be contrary to the terms of international law.”

INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW OBLIGATES THE UNITED STATES TO ADMINISTER THE LAWS OF THE HAWAIIAN KINGDOM

Despite over a century of occupation, international humanitarian law, otherwise known as the laws of war, obligates the United States to administer the laws of the occupied State. In 2018, United Nations Independent Expert, Dr. Alfred deZayas, sent a communication from Geneva to the State of Hawai‘i that read:

“As a professor of international law, the former Secretary of the UN Human Rights Committee, co-author of [the] book, The United Nations Human Rights Committee Case Law 1977-2008, and currently serving as the UN Independent Expert on the promotion of a democratic and equitable international order, I have come to understand that the lawful political status of the Hawaiian Islands is that of a sovereign nation-state in continuity; but a nation-state that is under a strange form of occupation by the United States resulting from an illegal military occupation and a fraudulent annexation. As such, international laws (the Hague and Geneva Conventions) require that governance and legal matters within the occupied territory of the Hawaiian Islands must be administered by the application of the laws of the occupied state (in this case, the Hawaiian Kingdom), not the domestic laws of the occupier (the United States).”

Violations of the provisions of the 1907 Hague Regulations and the 1949 Fourth Geneva Convention are war crimes. Professor William Schabas, recognized expert in international criminal law, determined in a 2019 legal opinion for the Hawaiian Royal Commission of Inquiry, that war crimes have and continue to be committed in the Hawaiian Islands since January 17, 1893. He states, “In addition to crimes listed in applicable treaties, war crimes are also recognized under customary international law. Customary international law applies to States regardless of whether they have ratified relevant treaties. The customary law of war crimes is thus applicable to the situation in Hawai‘i. Many of the war crimes set out in the first Additional Protocol and in the Rome Statute codify customary international law and are therefore applicable to the United States despite its failure to ratify the treaties.” And according to Professor Lenzerini in his 2019 legal opinion for the Royal Commission of Inquiry, that violations of human rights in the Hawaiian Kingdom “would first of all need to be treated as war crimes, which are primarily to be considered under the lens of international criminal law.”

CONCEALING THE ILLEGAL OCCUPATION THROUGH AMERICANIZATION—DENATIONALIZATION

How could such a travesty have gone unnoticed until now? The answer is obliteration of Hawaiian national consciousness through a process of denationalization. Predating the policy of Germanization in the German occupied State of Serbia from 1915-1918, a formal policy of Americanization was initiated in 1906 that sought to obliterate the national consciousness of the Hawaiian Kingdom in the minds of school children throughout the islands. Classroom instruction was in English and if the children spoke Hawaiian they were severely punished. The Hawaiian Gazette reported, “It will be remembered that at the time of the celebration of the birthday of Benjamin Franklin, an agitation was begun looking to a better observance of these notable national days in the schools, as tending to inculcate patriotism in a school population that needed that kind of teaching, perhaps, more than the mainland children do.”

In 1907, a reporter from New York’s Harper’s Weekly visited Ka‘iulani public school in Honolulu and showcased the seeds of indoctrination. The reporter wrote:

“At the suggestion of Mr. Babbitt, the principal, Mrs. Fraser, gave an order, and within ten seconds all of the 614 pupils of the school began to march out upon the great green lawn which surrounds the building.… Out upon the lawn marched the children, two by two, just as precise and orderly as you find them at home. With the ease that comes of long practice the classes marched and counter-marched until all were drawn up in a compact array facing a large American flag that was dancing in the northeast trade-wind forty feet above their heads.… ‘Attention!’ Mrs. Fraser commanded. The little regiment stood fast, arms at side, shoulders back, chests out, heads up, and every eye fixed upon the red, white and blue emblem that waived protectingly over them. ‘Salute!’ was the principal’s next command. Every right hand was raised, forefinger extended, and the six hundred and fourteen fresh, childish voices chanted as one voice: ‘We give our heads and our hearts to God and our Country! One Country! One Language! One Flag!’”

The word “inculcate” imports force such as to convince, implant, or to indoctrinate. Brainwashing is its colloquial term. Within three generations, the national consciousness of the Hawaiian Kingdom was effectively obliterated from the minds of the Hawaiian people.

THE RISE OF NATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS OF THE HAWAIIAN KINGDOM

The year 1993, which marked the 100th anniversary of the American invasion and occupation, began the resurgence of Hawaiian national consciousness. It was also the year that the Congress enacted a joint resolution apologizing for the United States role in illegally overthrowing the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Six years later on November 8, 1999, the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague accepted a dispute between Lance Larsen, a Hawaiian subject, and the restored Hawaiian government—the Council of Regency (Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom). Larsen alleged the Council of Regency was legally liable for “allowing the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws over the claimant’s person within the territorial jurisdiction of the Hawaiian Kingdom.” The Regency’s position was that it was not liable and that the United States was responsible under international humanitarian law. Due to the United States decision not to participate in the arbitral proceedings after being invited by the Regency and Larsen’s counsel, Larsen was unable to maintain his suit against the Hawaiian government.

These proceedings, however, drew international attention to the American occupation which prompted the NLG’s International Committee to form the Hawaiian Kingdom Subcommittee in March of 2019. The Subcommittee “provides legal support to the movement demanding that the U.S., as the occupier, comply with international humanitarian and human rights law within Hawaiian Kingdom territory, the occupied. This support includes organizing delegations and working with the United Nations, the International Committee of the Red Cross, and NGOs addressing U.S. violations of international law and the rights of Hawaiian nationals and other Protected Persons.”

In December of 2019, the NLG’s membership voted and passed a resolution where “the National Lawyers Guild calls upon the United States of America immediately to begin to comply with international humanitarian law in its prolonged and illegal occupation of the Hawaiian Islands.”

The National Lawyers Guild, whose membership includes lawyers, legal workers, jailhouse lawyers, and law students, was formed in 1937 as the United States’ first racially-integrated bar association to advocate for the protection of constitutional, human and civil rights.

This past Monday defense lawyers Dexter Kaiama and Stephen Laudig filed their response to the State of Hawai‘i Attorney General’s opposition to their clients’ motion to dismiss. They argued that the Attorney General “cannot be allowed to knowingly and with intent benefit from the ‘war crime’ of usurpation of sovereignty that consists in the ‘imposition of legislation or administrative measures by the occupying power,’ which, in effect, leads to the violation of international law by denying a Protected Person of the right to a fair and regular trial by a properly constituted court. The prohibition of ‘war crimes’ is a jus cogens norm under customary international law and neither the [Attorney General] nor this Court can derogate from these peremptory norms.”

Kaiama and Laudig represent Deena Oana-Hurwitz, Loretta and Walter Ritte, Pualani Kanakaole-Kanahele, Kaliko Kanaele, Gene P.K. Burke, Alika Desha and Desmon Haumea. Both attorneys are also members of the National Lawyers Guild that “provides legal support to the movement demanding that the U.S., as the occupier, comply with international humanitarian and human rights law within Hawaiian Kingdom territory, the occupied.”

After state law enforcement officers arrested 39 Kia‘i Mauna (protectors of the mountain) who were opposing the building of the Thirty-Meter Telescope (TMT) on Mauna Kea on July 17, 2019, the Attorney General filed charges of obstruction in the Hilo District Court. On behalf of the 8 defendants, Kaiama and Laudig filed their motions to dismiss on November 13, 2019, which provided clear and unequivocal evidence that because the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist under international law the District Court “is not a regularly constituted court” and therefore does not have lawful jurisdiction to preside over the case.

An opposition to the motion to dismiss was filed by the Attorney General on December 6, 2019. In its opposition, the Attorney General provided no counter evidence of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s existence and that the Hawaiian Islands have never been lawfully a part of the United States. Instead, the Attorney General argues three points as to why Judge Kanani Lauback should deny defendants’ motion to dismiss. The first argument is that the political question doctrine prevents courts from adjudicating the legality of the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the validity of the State of Hawai‘i. Second, the legal status of the State of Hawai‘i has been adjudicated. And, third, international law does not override acts of Congress.

On December 9, Kaiama and Laudig filed a reply that starts off by stating that the Attorney General’s “statement of relevant facts violates the principle of jus cogens and is not relevant to the Court’s consideration of the instant motion.” Jus cogens is a legal term that federal courts say “enjoy[s] the highest status within international law,” and as such cannot be denigrated. International crimes, which includes war crimes, are jus cogens norms.

In its reply, the defense pointed out that the unlawful imposition of United States laws and administrative policies constitute a war crime under customary international law. For their evidence, the defense cited a legal opinion written by Professor William Schabas, a leading expert in international criminal law and war crimes, titled Legal opinion on war crimes related to the United States occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom since 17 January 1893. The defense argues that all “three fit squarely within the provisions of United States internal law—being legislation and administrative rules, which customary international law precludes a State from invoking as justification for its failure to comply with Article 43 of the Hague Regulations.” Article 43 of the Hague Regulation is a ratified treaty by the United States that obligates an Occupying State to administer the laws of the Occupied State. In this case the Occupying State is the United States and the Occupied States is the Hawaiian Kingdom.

A hearing on the motion to dismiss is scheduled for 8:30am on Friday, December 13, 2019, at the Hilo District Court.

In response to over a century of the United States’ violations of international humanitarian law and the commission of war crimes with impunity that have occurred within the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom, the acting Council of Regency established the Royal Commission of Inquiry (Commission), by proclamation, on April 17, 2019. The Commission was established by “virtue of the prerogative of the Crown provisionally vested in [the Council of Regency] in accordance with Article 33 of the 1864 Constitution, and to ensure a full and thorough investigation into the violations of international humanitarian law and human rights within the territorial jurisdiction of the Hawaiian Kingdom.”

The Commission’s mandate “shall be to investigate the consequences of the United States’ belligerent occupation, including with regard to international law, humanitarian law and human rights, and the allegations of war crimes committed in that context”—Article 1(2). To accomplish this mandate, Dr. David Keanu Sai”—Article 1(1), who currently serves as Minister of the Interior and Minister of Foreign Affairs ad interim, shall head the Commission and has been authorized to seek “recognized experts in various fields”—Article 3, whose opinions shall form the basis of the Commission’s reports.

The Commission shall first come out with a preliminary report that will provide the “geographical scope and time span of the investigation”—Article 1(2), and the identification of the specific war crimes to be investigated as well as a list of human rights recognized during belligerent occupations. The preliminary report will be followed by periodic reports that will identify the perpetrators of these war crimes and human rights violations. These periodic reports will have the evidential basis of mens rea and actus reus that have a direct nexus to the elements that constitute a particular war crime(s) as provided in the legal opinion of Professor William Schabas. War crimes have no statute of limitations, and, for those war crimes that are recognized under customary international law, States are obligated to prosecute perpetrators of war crimes under its universal jurisdiction.

These reports “will be presented to the Council of Regency, the Contracting Powers of the 1907 Hague Convention, IV, respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land, the Contracting Powers of the 1949 Geneva Convention, IV, relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, the Contracting Powers of the 2002 Rome Statute, the United Nations, the International Committee of the Red Cross, and the National Lawyers Guild”—Article 1(3).

The Commission has been convened with experts in international law in the fields of State continuity, humanitarian law, human rights law and self-determination of a people of an existing State under belligerent occupation. These experts authored legal opinions for the Commission, which include: Professor Matthew Craven, University of London SOAS, School of Law; Professor William Schabas, Middlesex University London, School of Law; and Professor Federico Lenzerini, University of Siena (Italy), Department of Political and International Sciences. Dr. Sai, who is also from the University of Hawai‘i, will also provide his expertise in the legal and political history of Hawai‘i.

Dr. David Keanu Sai, Memorandum—Hawaiian Constitutional Governance (2019).

Dr. David Keanu Sai, Memorandum—United States Belligerent Occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom (2019).

Professor Matthew Craven, Legal Opinion—Continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom under international law (2002).

Professor William Schabas, Legal Opinion—War crimes related to the United States occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom since 17 January 1893 (2019).

Professor Federico Lenzerini, Legal Opinion—International Human Rights Law and Self-Determination of Peoples Related to the United States Occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom since 17 January 1893 (2019)

The United States’ Prolonged Occupation of Hawai‘i: War Crimes and Human Rights Violations

Date and Time: Tuesday, 15 October 2019 17:30-19:00 BST

Location: Middlesex University The College Building, 2nd Floor, C219-220 The Burroughs London NW4 4BT United Kingdom

Registration: The event is free and open to the public as well as faculty, staff and students of Middlesex University London. Click here to Register

About this Event: From a British Protectorate in 1794 to an Independent State in 1843, the Hawaiian Kingdom’s government was illegally overthrown by U.S. forces in 1893. U.S. President Cleveland, after conducting a presidential investigation into the overthrow, notified the Congress that the Hawaiian government was overthrown by an “act of war” and that the U.S. was responsible. Annexationists in the Congress thwarted Cleveland’s commitment, by exchange of notes with Queen Lili‘uokalani, to restore the Hawaiian government and Hawai‘i was unilaterally annexed in 1898 during the Spanish-American War after Cleveland left office in order to secure the islands as a military outpost. Today there are 118 U.S. military sites in the islands, headquarters for the U.S. Indo-Pacific Unified Military Command, and is currently targeted for nuclear strike by North Korea, China, and Russia.

This legal and political history of Hawai‘i has been kept from the international community until the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom arbitral proceedings were initiated in 1999 at the Permanent Court of Arbitration, The Hague, Netherlands. At the core of the dispute were the unlawful imposition of U.S. laws, which led to grave breaches of the Fourth Geneva Convention by the U.S. against Lance Larsen, a Hawaiian subject, and whether the Hawaiian Kingdom, by its Council of Regency, was liable for the unlawful imposition of U.S. laws in the territory of an occupied State.

This talk by Dr. Keanu Sai, who served as Agent for the Hawaiian Kingdom in the Larsen case, will provide a historical and legal context of the current situation in Hawai‘i and the mandate of the Royal Commission of Inquiry to investigate war crimes and human rights violations taking place in Hawai‘i. Dr. Sai encourages attendees to view beforehand “The acting Council of Regency: Exposing the American Occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom” at:

WAILUKU, Hawaii – In her second letter to University of Hawaii President David Lassner, Maui County Councilmember Tamara Paltin has reiterated her concern over what appears to be the invalidity of General Lease S-4191, originally granted to University of Hawaii by the Board of Land and Natural Resources in 1968 and now subleased to TMT.

President Lassner assured Paltin in his July 18th response to her July 12th letter that “the project has all approvals required by law.” However, his brief correspondence did not address the concerns for native tenant rights and the war crime of destruction of property presented in Paltin’s original letter.

Councilmember Paltin reminded President Lassner that the general public’s understanding of Hawaii’s legal and political history has evolved significantly since the lease was originally granted to the University of Hawaii. In her latest letter, Paltin has suggested that the information that has come to light since 1968, including that found in the Apology Resolution of 1993, sets the general lease in a new context.

Referencing this new understanding of Hawaii’s legal history, Paltin wrote, “The United States Congress, in its Apology Resolution in 1993 (107 Stat. 1512), admitted…the so-called transfer of Hawaiian government and crown lands, which included the ahupua‘a of Ka‘ohe, to the United States in 1898, was done ‘without the consent of or compensation to the Native Hawaiian people of Hawai‘i or their sovereign [Hawaiian Kingdom] government.’” Therefore, because the transfer of property occurred without consent, Paltin continued, the sublease to TMT is invalid.

Councilmember Paltin once again requested that President Lassner have the University’s legal counsel review the assessment of the situation presented in her original letter and defend the validity of the general and sublease.

A full copy of Councilmember Tamara Paltin’s 07/26/19 letter to UH President Lassner can be located at mauicounty.us/paltin/.

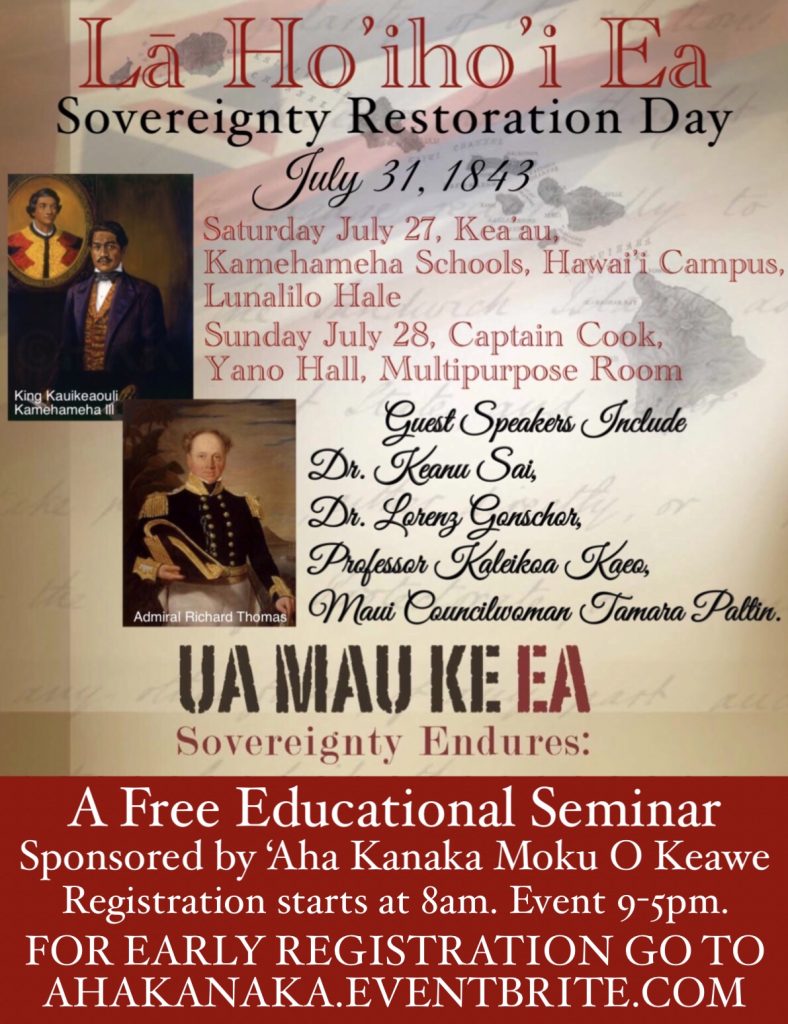

Today is July 31st which is a national holiday in the Hawaiian Kingdom called “Restoration day,” (La Ho‘iho‘i) and it is directly linked to another holiday observed on November 28th called “Independence day” (La Kuoko‘a). Here is a brief history of these two celebrated holidays.

In the summer of 1842, Kamehameha III moved forward to secure the position of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a recognized independent state under international law. He sought the formal recognition of Hawaiian independence from the three naval powers of the world at the time—Great Britain, France, and the United States. To accomplish this, Kamehameha III commissioned three envoys, Timoteo Ha‘alilio, William Richards, who at the time was still an American Citizen, and Sir George Simpson, a British subject. Of all three powers, it was the British that had a legal claim over the Hawaiian Islands through cession by Kamehameha I, but for political reasons the British could not openly exert its claim over the other two naval powers. Due to the islands prime economic and strategic location in the middle of the north Pacific, the political interest of all three powers was to ensure that none would have a greater interest than the other. This caused Kamehameha III “considerable embarrassment in managing his foreign relations, and…awakened the very strong desire that his Kingdom shall be formally acknowledged by the civilized nations of the world as a sovereign and independent State.”

While the envoys were on their diplomatic mission, a British Naval ship, HBMS Carysfort, under the command of Lord Paulet, entered Honolulu harbor on February 10, 1843, making outrageous demands on the Hawaiian government. Basing his actions on complaints made to him in letters from the British Consul, Richard Charlton, who was absent from the kingdom at the time, Paulet eventually seized control of the Hawaiian government on February 25, 1843, after threatening to level Honolulu with cannon fire. Kamehameha III was forced to surrender the kingdom, but did so under written protest and pending the outcome of the mission of his diplomats in Europe. News of Paulet’s action reached Admiral Richard Thomas of the British Admiralty, and he sailed from the Chilean port of Valparaiso and arrived in the islands on July 25, 1843. After a meeting with Kamehameha III, Admiral Thomas determined that Charlton’s complaints did not warrant a British takeover and ordered the restoration of the Hawaiian government, which took place in a grand ceremony on July 31, 1843. At a thanksgiving service after the ceremony, Kamehameha III proclaimed before a large crowd, ua mau ke ea o ka ‘aina i ka pono (the life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness). The King’s statement became the national motto.

The envoys eventually succeeded in getting formal international recognition of the Hawaiian Islands “as a sovereign and independent State.” Great Britain and France formally recognized Hawaiian sovereignty on November 28, 1843 by joint proclamation at the Court of London, and the United States followed on July 6, 1844 by a letter of Secretary of State John C. Calhoun. The Hawaiian Islands became the first Polynesian nation to be recognized as an independent and sovereign State.

The ceremony that took place on July 31 occurred at a place we know today as “Thomas Square” park, which honors Admiral Thomas, and the roads that run along Thomas Square today are “Beretania,” which is Hawaiian for “Britain,” and “Victoria,” in honor of Queen Victoria who was the reigning British Monarch at the time the restoration of the government and recognition of Hawaiian independence took place.