Dr. Keanu Sai on Keep It Aloha Podcast

5

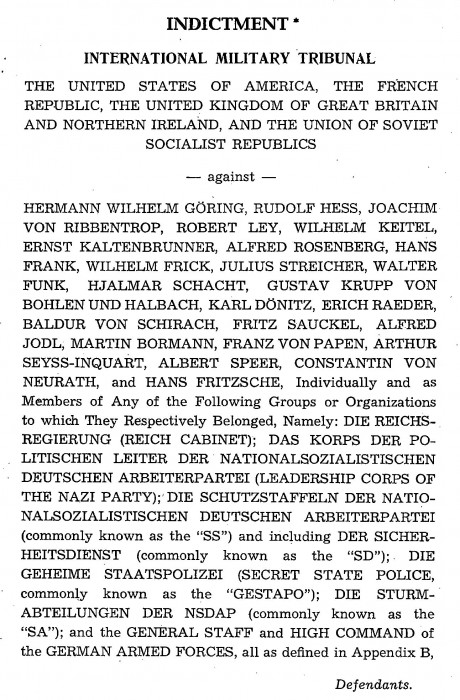

There is confusion on the role and function of the International Criminal Court (ICC) regarding the prosecution of war crimes being committed in the Hawaiian Kingdom. What is its role on this subject?

The ICC was established in 2002 by a treaty called the Rome Statute. Although the United States participated in negotiations and signed the treaty that eventually established the court, President Bill Clinton did not submit the treaty to the Senate for ratification. President George W. Bush, in 2002, sent a diplomatic note to the United Nations Secretary-General that the United States intends not to ratify the treaty. There are currently 137 countries that signed the treaty, but there are 124 countries that are State Parties to the Rome Statute.

According to the Rome Statute, the 124 countries have committed to be the ones primarily responsible for the prosecution of war crimes called complementarity jurisdiction. Article 1 of the Rome Statute states that the ICC “shall be a permanent institution and shall have the power to exercise its jurisdiction over persons for the most serious crimes of international concern, as referred to in this Statute, and shall be complementary to national criminal jurisdictions.”

This principle of complementarity is implemented through Articles 17 and 53 of the Rome Statute. The principle states that the ICC will not accept a case if a State Party with jurisdiction over it is already investigating it or unless the State Party is unwilling or genuinely unable to proceed with an investigation. According to Human Rights Watch:

Under international law, states have a responsibility to investigate and appropriately prosecute (or extradite for prosecution) suspected perpetrators of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and other international crimes. The ICC does not shift this responsibility. It is a court of last resort. Under what is known as the “principle of complementarity,” the ICC may only exercise its jurisdiction when a country is either unwilling or genuinely unable to investigate and prosecute these grave crimes.

On November 28, 2012, the Hawaiian Kingdom acceded to the Rome Statute and deposited its instrument of accession with the United Nations Secretary-General in New York City the following month on December 12, 2012. Under the principle of complementarity and its responsibility to investigate war crimes committed in the Hawaiian Islands, the Royal Commission of Inquiry (RCI) was established by proclamation of the Council of Regency on April 17, 2019. According to Article 2 of the proclamation:

The purpose of the Royal Commission shall be to investigate the consequences of the United States’ belligerent occupation, including with regard to international law, humanitarian law and human rights, and the allegations of war crimes committed in that context. The geographical scope and time span of the investigation will be sufficiently broad and be determined by the head of the Royal Commission.

The RCI has already conducted 18 war criminal investigations and published these war criminal reports on its website. The failure of the State of Hawai‘i to transform itself into a U.S. military government to administer the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom has put a temporary hold on prosecutions. However, once the U.S. military government is established, prosecutions will begin. As a result, the ICC does not have jurisdiction over the Hawaiian Islands to investigate war crimes because the RCI has already initiated its investigative authority and published its war criminal reports.

Under the principle of complementarity, the other State Parties to the Rome Statute could initiate prosecution proceedings for those persons who were the subjects of the RCI war criminal reports when these individuals enter the territory of a State Party.

CLARIFICATION: At first glance, it would appear that Major General Hara can escape criminal culpability by not transforming the State of Hawai‘i into a U.S. military government. This is incorrect because MG Hara is not the subject of a war criminal report by the RCI yet. However, he will be the subject of a war criminal report if he does not delegate full authority to Brigadier General Stephen Logan who must establish the military government by 12 noon on July 31, 2024.

If MG Hara is derelict in the performance of his duties by not delegating authority to BG Logan, he would be the subject of an RCI war criminal report for the war crime by omission. From the date of the publication of MG Hara’s war criminal report, BG Logan will have one week to transform the State of Hawai‘i into a military government.

If BG Logan is derelict in the performance of his duties to establish a military government, he would be the subject of an RCI war criminal report for the war crime by omission. From the date of the publication of BG Logan’s war criminal report, Colonel David Hatcher, Commander of the 29th Infantry Brigade, and who is next in the chain of command below BG Logan, will have one week to transform the State of Hawai‘i into a military government.

These chain of events will continue down the chain of command of the entire Hawai‘i Army National Guard, and possibly the Hawai‘i Air National Guard, until there is someone who sees the “writing on the wall” that he/she either performs their military duty or become a war criminal subject to prosecution.

On July 1, 2024, Dr. Keanu Sai, as Head of the Royal Commission of Inquiry, sent a letter to State of Hawai‘i Adjutant General Kenneth Hara giving him notice to delegate authority and title to Deputy Adjutant General Brigadier General Stephen Logan so that he can establish a Military Government of Hawai‘i no later than 1200 hours on July 31, 2024. There are severe consequences for failure to do so that could implicate the chain of command of the Army National Guard for the war crime by omission. Here is a link to the letter.

Major General Hara:

In my last communication to you, on behalf of the Council of Regency, dated February 10, 2024, I made a “final appeal for you to perform your duty of transforming the State of Hawai‘i into a military government on February 17, 2024, in accordance with Article 43 of the 1907 Hague Regulations, Article 64 of the Fourth Geneva Convention, and Army regulations.” You ignored that appeal despite your admittance, on July 27, 2023, to John “Doza” Enos that the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist.

This communication is not an appeal, but rather a notice to perform your duty, as the theater commander in the occupied State of the Hawaiian Kingdom, to establish a military government of Hawai‘i by 1200 hours on July 31, 2024. If you fail to do so, you will be the subject of a war criminal report by the Royal Commission of Inquiry (“RCI”) for the war crime by omission. The elements of the war crime by omission are the Uniform Code of Military Justice’s (“UCMJ”) offenses under Article 92(1) for failure to obey order or regulation, and Article 92(3) for dereliction in the performances of duties. The maximum punishment for Article 92(1) is dishonorable discharge, forfeiture of all pay and allowances, and confinement for 2 years. The maximum punishment for Article 92(3) is bad-conduct discharge, forfeiture of all pay and allowances, and confinement for 6 months.

Despite the prolonged nature and illegality of the American occupation since January 17, 1893, the sovereignty has remained vested in the Hawaiian Kingdom. In 1999, this was confirmed in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, PCA Case no. 1999-01. In that case, the Permanent Court of Arbitration (“PCA”) recognized the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State, under international law, and the Council of Regency as its government. At the center of the Larsen case was the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws within the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom, which is the war crime of usurpation of sovereignty. This fact renders the State of Hawai‘i unlawful because it was established by congressional legislation in 1959, which is an American municipal law. Ex injuria jus non oritur (law does not arise from injustice) is a recognized principle of international law.

After the Council of Regency returned from the oral proceedings, held at the PCA, in December of 2000, it directly addressed the devastating effects of denationalization through Americanization. This effectively erased the national consciousness of the Hawaiian Kingdom in the minds of the Hawaiian population and replaced it with an American national consciousness that created a false narrative that Hawai‘i became a part of the United States. Denationalization, under customary international law, is a war crime.

The Council of Regency decided to address the effects of Americanization through academic and scholarly research at the University of Hawai‘i. The Council of Regency’s decision was guided by paragraph 495—Remedies of Injured Belligerent, FM 27-10, that states, “[i]n the event of violation of the law of war, the injured party may legally resort to remedial action of the following […] a. [p]ublication of the facts, with a view to influencing public opinion against the offending belligerent.” Since then, a plethora of doctoral dissertations, master’s theses, peer review articles, and books have been published on the topic of the American occupation. The latest peer review articles, by myself as Head of the RCI, and by Professor Federico Lenzerini as Deputy Head of the RCI, were published in June of 2024 by the International Review of Contemporary Law:

Professor Federico Lenzerini, “Military Occupation, Sovereignty, and the ex injuria jus non oritur Principle. Complying with the Supreme Imperative of Suppressing “Acts of Aggression or Other Breaches of the Peace” à la carte?,” 6(2) International Review of Contemporary Law 58-67 (2024).

Dr. David Keanu Sai, “All States have a Responsibility to Protect their Population from War Crimes—Usurpation of Sovereignty During Military Occupation of the Hawaiian Islands,” 6(2) International Review of Contemporary Law 72-81 (2024).

In addition, legal opinions on this subject were authored by experts in the various fields of international law:

Professor Matthew Craven, “Continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State under International Law,” in David Keanu Sai (ed.) Royal Commission of Inquiry: Investigating War Crimes and Human Rights Violations Committed in the Hawaiian Kingdom 125-149 (2020).

Professor William Schabas, “War Crimes Related to the United States Belligerent Occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom,” in David Keanu Sai (ed.) Royal Commission of Inquiry: Investigating War Crimes and Human Rights Violations Committed in the Hawaiian Kingdom 151-169 (2020).

Professor Federico Lenzerini, “International Human Rights Law and Self-Determination of Peoples related to the United States Occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom,” in David Keanu Sai (ed.) Royal Commission of Inquiry: Investigating War Crimes and Human Rights Violations Committed in the Hawaiian Kingdom 173-216 (2020).

Professor Federico Lenzerini, “Legal Opinion on the Authority of the Council of Regency of the Hawaiian Kingdom,” 3 Hawaiian Journal of Law and Politics 317-333 (2021).

Professor Federico Lenzerini, Legal Opinion of Civil Law on Juridical Fact of the Hawaiian State and the Consequential Juridical Act by the Permanent Court of Arbitration (December 5, 2021).

Notwithstanding your failure to obey an Army regulation and dereliction of duty, both being offenses under the UCMJ and the war crime by omission, you are the most senior general officer of the State of Hawai‘i Department of Defense. And despite your public announcement that you will be retiring as the Adjutant General on October 1, 2024, and resigning from the U.S. Army on November 1, 2024, you remain the theater commander over the occupied territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom. You are, therefore, responsible for establishing a military government in accordance with paragraph 3, FM 27-5. Article 43 of the 1907 Hague Regulations and Article 64 of the 1949 Fourth Geneva Convention imposes the obligation on the commander in occupied territory to establish a military government to administer the laws of the occupied State. Furthermore, paragraph 2-37, FM 41-10, states that “commanders are under a legal obligation imposed by international law.”

However, since paragraph 3 of FM 27-5 also states that you also have “authority to delegate authority and title, in whole or in part, to a subordinate commander” to perform the duty of establishing a military government. The RCI will consider this provision as time sensitive to conclude willfulness, on your part, to not delegate authority and title, thereby, completing the elements necessary for the war crime by omission. Therefore, you will delegate full authority and title to Brigadier General Stephen Logan so that he can establish a Military Government of Hawai‘i no later than 1200 hours on July 31, 2024. BG Logan will be guided in the establishment of a military government by the RCI’s memorandum on bringing the American occupation of Hawai‘i to an end by establishing an American military government (June 22, 2024), and by the Council of Regency’s Operational Plan for transitioning the State of Hawai‘i into a Military Government (August 14, 2023).

Should you fail to delegate full authority and title to BG Logan, the RCI will conclude that your conduct is “willful,” and you will be the subject of a war criminal report for the war crime by omission. Military governments are under an obligation, under international law, to prosecute war criminals in occupied territory, and the Army National Guard is obligated to hold you accountable, by court martial, for violating Articles 92(1) and (3) of the UCMJ. The war criminal report for your war crime by omission will be based on the elements of the offenses of the UCMJ. Thus, your court martial will be based on the evidence provided in the war criminal report. Military law provides for your prosecution under the UCMJ, while international law provides for your prosecution for war crimes. One prosecution does not cancel out the other prosecution. Furthermore, war crimes have no statutes of limitations. In 2022, Germany prosecuted a 97-years old woman for Nazi war crimes.

I am aware that you stated to a former Adjutant General that State of Hawai‘i Attorney General Anne E. Lopez, who is a civilian, instructed you and Brigadier General Stephen Logan to ignore me and any organization calling for the performance of a military duty to establish a military government. This conduct is not a valid defense for disobedience of an Army regulation and dereliction of duty because Mrs. Lopez is a civilian interfering with a military duty.

This is tantamount to a soldier, under your command, refusing to follow your order given him because a civilian instructed him to ignore you. For you not to perform your military duty is to show that there is no such military duty to perform because the Hawaiian Kingdom does not continue to exist as an occupied State under international law. There is no such evidence. The RCI considers Mrs. Lopez’s conduct and action to be an accomplice to the war crime by omission and she will be included in your war criminal report should you fail to delegate your authority to BG Logan.

Once the war criminal report is made public on the RCI’s website, BG Logan is duty bound to immediately assume the chain of command and perform the duty of establishing a military government. The RCI will give BG Logan one week from the date of the war criminal report to establish a military government. Should BG Logan also be “willful” in disobeying an Army regulation and of dereliction of duty, then he will be the subject of a war criminal report. Thereafter, the next in line of the Army National Guard shall assume the chain of command. This will continue until a member of the Army National Guard performs the duty of establishing a military government.

On June 15, 2024, the Royal Order of Kamehameha I sent a letter to State of Hawai‘i Adjutant General Major General Kenneth Hara to perform his duty of transforming the State of Hawai‘i into a Military Government. Here is a link to download the letter.

Aloha Major General Hara:

We the members of the Royal Order of Kamehameha I (including Na Wahine O Kamehameha), was established in the early 1900s to maintain a connection to our country, the Hawaiian Kingdom, despite the unlawful overthrow of our country’s government on January 17, 1893, by the United States.

Our people have suffered greatly in the aftermath of the overthrow, but we, as Native Hawaiian subjects, have survived. Our predecessors, who established the Royal Order of Kamehameha I, had a national consciousness of their country that we didn’t have because of the Americanization of these islands. We, today, were taught that our country no longer existed and that we are now American citizens. We now know that this is not true.

When the Government was restored in 1997, the Council of Regency embarked on a monumental task to ho‘oponopono (right the wrong) from a legal standpoint. Their success to get the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague, Netherlands, to recognize the continued existence of our country and the Council of Regency as our government was no small task. When the Council of Regency returned from the Netherlands in 2000, they embarked on an educational campaign to restore the national consciousness of the Hawaiian Kingdom in the minds of its people. This led to classes being taught on the American occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom at the University of Hawai‘i, High Schools, Middle Schools, Elementary Schools, and Preschools throughout the Hawaiian Islands.

In 2018, the Hawai‘i State Teachers Association was able to get their resolution passed at the annual conference of the National Education Association in Boston, Massachusetts. The resolution stated, “The NEA will publish an article that documents the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Monarchy in 1893, the prolonged illegal occupation of the United States in the Hawaiian Kingdom and the harmful effects that this occupation has had on the Hawaiian people and resources of the land.” The HSTA asked Dr. Keanu Sai to write three articles, which were published on the NEA website. Dr. Sai is the Chairman of the Council of Regency, and he led the legal team for the Hawaiian Kingdom at the Permanent of Court of Arbitration in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom.

Because of this educational campaign, we are now aware that our country still exists and, as a people, we must owe allegiance to the Hawaiian Kingdom as our predecessors did. This is not a choice, but an obligation as Hawaiian subjects. We also acknowledge that the Council of Regency is our government that was lawfully established under extraordinary circumstances, and we support its effort to bring compliance with the law of occupation by the State of Hawai‘i on behalf of the United States, which will eventually bring the American occupation to close. When this happens, our Legislative Assembly will be brought into session so that Hawaiian subjects can elect a Regency of our choosing. The Council of Regency is currently operating in an acting capacity that is allowed under Hawaiian law.

We have read the Minister of the Interior’s memorandum dated April 26, 2024 (https://hawaiiankingdom.org/pdf/Memo_re_Rights_of_Hawaiians_(4.26.24).pdf), and the Council of Regency’s Operational Plan for the State of Hawai‘i to transform into a Military Government (https://hawaiiankingdom.org/pdf/HK_Operational_Plan_of_Transition.pdf), and we support this plan. After watching Dr. Sai’s presentation to the Maui County Council on March 6, 2024 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X-VIA_3GD2A), we were made aware of your reluctance to carry out your duty to transform the State of Hawai‘i into a Military Government.

Because of the high cost of living brought here because of the unlawful American presence, the majority of Native Hawaiians now reside in the United States. The U.S. Census reported that in 2020, that of the total of 680,442 Native Hawaiians, 53 percent live in the United States. The driving factors that led to the move were not being able to afford a home and adequate health care. Dr. Sai, as the Minister of the Interior, clearly explains this in his memorandum where he states,

While the State of Hawai‘i has yet to transform itself into a Military Government and proclaim the provisional laws, as proclaimed by the Council of Regency, that brings Hawaiian Kingdom laws up to date, Hawaiian Kingdom laws as they were prior to January 17, 1893, continue to exist. The greatest dilemma for aboriginal Hawaiians today is having a home and health care. Average cost of a home today is $820,000.00. And health care insurance for a family of 4 is at $1,500 a month. According to the Office of Hawaiian Affairs’ Native Hawaiian Health Fact Sheet 2017, “Today, Native Hawaiians are perhaps the single racial group with the highest health risk in the State of Hawai‘i. This risk stems from high economic and cultural stress, lifestyle and risk behaviors, and late or lack of access to health care.”

Under Hawaiian Kingdom laws, aboriginal Hawaiian subjects are the recipients of free health care at Queen’s Hospital and its outlets across the islands. In its budget, the Hawaiian Legislative Assembly would allocate money to the Queen’s Hospital for the healthcare of aboriginal Hawaiian subjects. The United States stopped allocating moneys from its Territory of Hawai‘i Legislature in 1909. Aboriginal Hawaiian subjects are also able to acquire up to 50 acres of public lands at $20.00 per acre under the 1850 Kuleana Act. With the current rate of construction costs, which includes building material and labor, an aboriginal Hawaiian subject can build 3-bedroom, 1-bath home for $100,000.00.

Hawaiian Kingdom laws also provide for fishing rights that extend out to the first reef or where there is no reef, out to 1 mile, exclusively for all Hawaiian subjects and lawfully resident aliens of the land divisions called ahupua‘a or ‘ili. From that point out to 12 nautical miles, all Hawaiian subjects and lawfully resident aliens have exclusive access to economic activity, such as mining underwater resources and fishing. Once the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea is acceded to by the Council of Regency, this exclusive access to economic activity will extend out to 200 miles called the Exclusive Economic Zone.

On behalf of the members of the Royal Order, I respectfully call upon you to carry out your duty to proclaim the transformation of the State of Hawai‘i into a Military Government so that all Hawaiian subjects, and their families, would be able to exercise their rights secured to them under Hawaiian Kingdom law and protected by the international law of occupation. We urge you to work with the Council of Regency in making sure this transition is not only lawful but is done for the benefit of all Hawaiian subjects that are allowed under Hawaiian Kingdom law, the 1907 Hague Regulations and the 1949 Fourth Geneva Convention.

The International Review of Contemporary Law released its volume 6, no. 2, earlier this month. The theme of this journal is “77 Years of the United Nations Charter.” The Head, Dr. Keanu Sai, and Deputy Head, Professor Federico Lenzerini, of the Royal Commission of Inquiry that investigates war crimes and human rights violations committed in the Hawaiian Kingdom, each had an article published in the journal.

Dr. Sai’s article is titled “All States have a Responsibility to Protect their Population from War Crimes—Usurpation of Sovereignty During Military Occupation of the Hawaiian Islands.” Dr. Sai’s article opened with:

At the United Nations World Summit in 2005, the Responsibility to Protect was unanimously adopted. The principle of the Responsibility to Protect has three pillars: (1) every State has the Responsibility to Protect its populations from four mass atrocity crimes—genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and ethnic cleansing; (2) the wider international community has the responsibility to encourage and assist individual States in meeting that responsibility; and (3) if a state is manifestly failing to protect its populations, the international community must be prepared to take appropriate collective action, in a timely and decisive manner and in accordance with the UN Charter. In 2009, the General Assembly reaffirmed the three pillars of a State’s responsibility to protect their populations from war crimes and crimes against humanity. And in 2021, the General Assembly passed a resolution on “The responsibility to protect and the prevention of genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity.” The third pillar, which may call into action State intervention, can become controversial.

Rule 158 of the International Committee of the Red Cross Study on Customary International Humanitarian Law specifies that “States must investigate war crimes allegedly committed by their nationals or armed forces, or on their territory, and, if appropriate, prosecute the suspects. They must also investigate other war crimes over which they have jurisdiction and, if appropriate, prosecute the suspects.” This “rule that States must investigate war crimes and prosecute the suspects is set forth in numerous military manuals, with respect to grave breaches, but also more broadly with respect to war crimes in general.”

Determined to hold to account individuals who have committed war crimes and human rights violations throughout the Hawaiian Islands, being the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom, the Council of Regency, by proclamation on 17 April 2019, established a Royal Commission of Inquiry (“RCI”) in similar fashion to the United States proposal of establishing a Commission of Inquiry after the First World War “to consider generally the relative culpability of the authors of the war and also the question of their culpability as to the violations of the laws and customs of war committed during its course.” The author serves as Head of the RCI and Professor Federico Lenzerini from the University of Siena, Italy, as its Deputy Head. This article will address the first pillar of the principle of Responsibility to Protect.

Professor Lenzerini’s article is titled “Military Occupation, Sovereignty, and the ex injuria jus non oritur Principle. Complying with the Supreme Imperative of Suppressing ‘Acts of Aggression or Other Breaches of the Peace’ à la carte?” After covering the Iraqi military occupation of Kuwait and the Russian military occupation of Ukraine, Professor Lenzerini’s article draws attention to the American military occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Professor Lenzerini writes:

As a factual situation, the occupation of Hawai‘i by the US does not substantially differ from the examples provided in the previous section. Since the end of the XIX Century, however, almost no significant positions have been taken by the international community and its members against the illegality of the American annexation of the Hawaiian territory. Certainly, the level of military force used in order to overthrow the Hawaiian Kingdom was not even comparable to that employed in Kuwait, Donbass or even in Crimea. In terms of the illegality of the occupation, however, this circumstance is irrelevant, because, as seen in section 2 above, the rules of international humanitarian law regulating military occupation apply even when the latter does not meet any armed resistance by the troops or the people of the occupied territory. The only significant difference between the case of Hawai‘i and the other examples described in this article rests in the circumstance that the former occurred well before the establishment of the United Nations, and the resulting acquisition of sovereignty by the US over the Hawaiian territory was already consolidated at the time of their establishment. Is this circumstance sufficient to uphold the position according to which the occupation of Hawai‘i should be treated differently from the other cases? An attempt to provide an answer to this question will be carried out in the next section, through examining the possible arguments which may be used to either support or refute such a position.

In the next section, Professor Lenzerini undermines the argument that international law in 1893 allowed the occupying State, in this case the United States, to have acquired the sovereignty of the Hawaiian Kingdom because the United States exercised effective control over the territory. He wrote:

The main argument that could be used to deny the illegality of the US occupation of Hawai‘i rests in the doctrine of intertemporal law. According to this doctrine, the legality of a situation “must be appraised […] in the light of the rules of international law as they existed at that time, and not as they exist today”. In other words, a State can be considered responsible of a violation of international law—implying the determination of the consequent “secondary” obligation for that State to restore legality—only if its behaviour was prohibited by rules already in force at the time when it was held. In the event that one should ascertain that at the time of the occupation of Hawai‘i by the US international law did not yet prohibit the annexation of a foreign territory as a consequence of the occupation itself, the logical conclusion, in principle, would be that the legality of the annexation of Hawai‘i by the United States cannot reasonably be challenged. In reality even this conclusion could probably be disputed through using the argument of “continuing violations”, by virtue of the violations of international law which continue to be produced today as a consequence of the American occupation and of its perpetuation. In fact, it is a general principle of international law on State responsibility that “[t]he breach of an international obligation by an act of a State having a continuing character extends over the entire period during which the act continues and remains not in conformity with the international obligation”.

However, it appears that there is no need to rely on this argument, for the reason that also an intertemporal-law-based perspective confirms the illegality—under international law—of the annexation of the Hawaiian Islands by the US. In fact, as regards in particular the topic of military occupation, the affirmation of the ex injuria jus non oritur rule predated the Stimson doctrine, because it was already consolidated as a principle of general international law since the XVIII Century. In fact, “[i]n the course of the nineteenth century, the concept of occupation as conquest was gradually abandoned in favour of a model of occupation based on the temporary control and administration of the occupied territory, the fate of which could be determined only by a peace treaty”, in other words, “the fundamental principle of occupation law accepted by mid-to-late 19th-century publicists was that an occupant could not alter the political order of territory”. Consistently, “[l]es États qui se font la guerre rompent entre eux les liens formés par le droit des gens en temps de paix; mais il ne dépend pas d’eux d’anéantir les faits sur lesquels repose ce droit des gens. Ils ne peuvent détruire ni la souveraineté des États, ni leur indépendance, ni la dépendance mutuelle des nations”. This was already confirmed by domestic and international practice contemporary to the occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom by the United States. For instance, in 1915, in a judgment concerning the case of a person who was arrested in a part of Russian Poland occupied by Germany and deported to the German territory without the consent of Russian authorities, the Supreme Court of Germany held that an occupied enemy territory remained enemy and did not become national territory of the occupant as a result of the occupation.

Professor Lenzerini when on to state:

In light of the foregoing, it appears that the theories according to which the effective and consolidated occupation of a territory would determine the acquisition of sovereignty by the occupying power over that territory—although supported by eminent scholars—must be confuted. Consequently, under international law, “le transfert de souveraineté ne peut être considéré comme effectué judiquement que par l’entrée en vigueur du Traité qui le stipule et à dater du jour de cette mise en vigueur”, which means that “[t]he only form in which a cession [of territory] can be effected is an agreement embodied in a treaty between the ceding and the acquiring State. Such treaty may be through the outcome of peaceable negotiations or of war.” This conclusion had been confirmed, among others, by the US Supreme Court Justice John Marshall in 1928, holding that the fate of a territory subjected to military occupation had to be “determined at the treaty of peace.”

There is no treaty where the Hawaiian Kingdom ceded its territorial sovereignty to the United States. The American military occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom is now at 131 years.

There’s been a change in schedule for Dr. Keanu Sai’s presentation at the Festival of the Pacific Culture and Arts held at the Hawai‘i Convention Center. Dr. Sai was previously scheduled to present on the American Occupation at 11:00am to 12:30pm in the Kaua‘i Room 311. It is now changed to 10:30am to 12 noon in the same Kaua‘i Room 311.

Dr. Keanu Sai will do a presentation on the American occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom at the 13th Festival of Pacific Arts and Culture. Dr. Sai’s presentation will be on Thursday, June 13, 2024, from 11:00am to 12:30pm in the Kaua‘i Room 311 at the Hawai‘i Convention Center.

The Festival of Pacific Arts & Culture (FestPAC) is the world’s largest celebration of indigenous Pacific Islanders. The South Pacific Commission (now The Pacific Community – SPC) launched this dynamic showcase of arts and culture in 1972 to halt the erosion of traditional practices through ongoing cultural exchange. It is a vibrant and culturally enriching event celebrating the unique traditions, artistry, and diverse cultures of the Pacific region. FestPAC serves as a platform for Pacific Island nations to showcase their rich heritage and artistic talents.

The roots of FestPAC trace back to the 1970s when Pacific Island nations commenced discussion on the need to preserve and promote their unique cultural identities. The hope was to create a space where Pacific Islanders could convene to share their traditional arts, crafts, music, dance, and oral traditions with the world. This initiative was driven by the desire to strengthen cultural bonds among Pacific Island communities and foster a greater understanding of their cultures.

The inaugural Festival of Pacific Art and Culture took place in 1972 in Suva, Fiji. Over the years, FestPAC has evolved and grown in stature, becoming a highly anticipated event for both Pacific Islanders and visitors from around the world. The festival has not only preserved traditional arts and culture but has also served as a platform for contemporary Pacific Island artists to express their creativity and address contemporary issues.

One of the festival’s most important objectives is to promote cultural exchange and understanding among the participating nations. It provides an opportunity for artists and cultural practitioners to learn from each other, share stories, and forge lasting connections. FestPAC serves as a reminder of the common heritage that binds Pacific Island nations and highlights the importance of preserving and celebrating their heritage.

Since its inception, FestPAC has been hosted by different Pacific Island nations on a rotational basis. Each host country takes on the responsibility of organizing and hosting the festival, providing a unique opportunity to showcase their own culture and hospitality. Host nations have all played a pivotal role in the festival’s success. They have worked tirelessly to create a welcoming and vibrant atmosphere for artists and visitors alike, ensuring that FestPAC remains a foundation of cultural exchange and celebration in the Pacific.

In an unprecedented move by 37 Police Officers, both active and retired across the Hawaiian Islands, they have collectively called upon the State of Hawai‘i Adjutant General Army Major General Kenneth Hara to comply with international law and the law of occupation.

International law requires that since the State of Hawai‘i is in effective control of 10,931 square miles of Hawaiian territory, and the federal government is in effective control of less than 500 square miles, it is the State of Hawai‘i that is responsible for transforming itself into a military government. Under the law of occupation, a military government is responsible for temporarily administering the laws of the occupied State, the Hawaiian Kingdom, until a peace treaty has been agreed upon between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States. The peace treaty will bring the occupation to an end. In the meantime, a military government will enforce the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and it is only through effective control of territory that it can enforce Hawaiian laws.

On January 17, 1893, the insurgents, calling themselves the executive and advisory councils under the armed protection of U.S. Marines, only replaced the Queen, her Cabinet of 4 Ministers, and the Marshal. Everyone in the executive and judicial branches of government were told to stay in place and sign oaths of allegiance to the new regime. The civilian government name was changed from the Hawaiian Kingdom Government to the provisional government. On July 4, 1894, the name was changed to the Republic of Hawai‘i.

After the United States unlawfully annexed the Hawaiian Islands in 1898, the name of the government was changed to the Territory of Hawai‘i in 1900. In 1959, the name was again changed to the State of Hawai‘i. The State of Hawai‘i is the civilian government of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Under international law, this civilian government’s executive and judicial branches of government continue with the exception of the legislative branch. Major General Hara, who would be called the Military Governor, only replaces civilian Governor Josh Green. Major General Hara is the highest Army general officer in the State of Hawai‘i command structure.

According to the U.S. Manual for Courts-Martial, a duty may be imposed by treaty, statute, regulation, lawful order, standard operating procedure, or custom of the Service. In this case, MG Hara’s duty is imposed upon him by Article 43 of the 1907 Hague Regulations, and U.S. Department of Defense Directive 5000.1, which states it is the function of the Army in occupied territories abroad to provide for the establishment of a military government pending transfer of this responsibility to the Hawaiian Kingdom Government when the occupation comes to an end. The Council of Regency’s Operational Plan for transitioning the State of Hawai‘i into a Military Government explains this in full.

On May 29, 2024, these 37 Police Officers mailed a letter to Major General Hara, Deputy Adjutant General Brigadier General Stephen Logan, and Staff Judge Advocate Lloyd Phelps explaining why they have taken this position. The letter stated:

We hope this letter finds you in good health and high spirits. We are writing to you on behalf of a deeply concerned group of Active and Retired law enforcement officers throughout the Hawaiian Islands, about the current governance of Hawaii and its impact on the vested rights of Hawaiian subjects under Hawaiian Law.

As you are well aware, the historical transition of Hawai‘i from a sovereign kingdom to a U.S. state is fraught with significant legal and ethical issues. The overthrow of the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893 and its subsequent annexation by the United States in 1898 continue to be an illegal act. The Hawaiian Kingdom was recognized as a Sovereign State by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague, Netherlands, in Larsen vs. Hawaiian Kingdom (https://pca-cpa.org/en/cases/35/).

At the center of the dispute, as stated on the PCA’s website on the Larsen case, was the unlawful imposition of American laws over Lance Larsen, a Hawaiian subject, that led to an unfair trial and incarceration. It was a police officer, who believed that Hawai‘i was a part of the United States and that he was carrying out his lawful duties, that cited Mr. Larsen, which led to his incarceration. That police officer now knows otherwise and so do we. This is not the United States but rather the Hawaiian Kingdom as an occupied State under international law.

It is deeply troubling that the State of Hawaii has not been transitioned into a military government as mandated by international law. This failure of transition places current police officers on duty that they may be held accountable for unlawfully enforcing American laws. This very issue was brought to the attention of the Maui County Corporation Counsel by Maui Police Chief John Pelletier in 2022. In their request to Chief Pelletier, which is attached, Detective Kamuela Mawae and Patrol Officer Scott McCalister, stated:

We are humbly requesting that either Chief John Pelletier or Deputy Chief Charles Hank III formally request legal services from Corporation Counsel to conduct a legal analysis of Hawai‘i’s current political status considering International Law and to assure us, and the rest of the Police Officers throughout the State of Hawai‘i, that we are not violating International Law by enforcing U.S. domestic laws within what the federal lawsuit calls the Hawaiian Kingdom that continues to exist as a nation state under international law despite its government being overthrown by the United States on 01/17/1893.

Police Chief Pelletier did make a formal request to Corporation Counsel, but they did not act upon the request, which did not settle the issue and the possible liability that Police Officers face.

Your failure to initiate such a transition may be construed as a violation of the 1907 Hague Regulations and the 1949 Geneva Convention, which outlines the obligations of occupying powers. Also, your actions, or lack thereof, deprive Hawaiian subjects of the protections and rights they are entitled to under Hawaiian Kingdom laws and international humanitarian law. According to the Geneva Convention, occupying powers are obligated to respect the laws in force in the occupied territory and protect the rights of its inhabitants. Failure to comply with these obligations constitutes a serious violation and can result in accountability for war crimes for individuals in positions of authority.

The absence of a military government perpetuates an unlawful governance structure that has deprived the rights of Hawaiian subjects which is now at 131 years. The unique status of these rights is explained at this blog article on the Council of Regency’s weblog titled “It’s About Law—Native Hawaiian Rights are at a Critical Point for the State of Hawai‘i to Comply with the Law of Occupation” (https://hawaiiankingdom.org/blog/native-hawaiians-are-at-a-critical-point-for-the-state-of-hawaii-to-comply-with-the-law-of-occupation/). It is imperative that steps be taken to rectify these historical injustices and ensure the protection of the vested rights of Hawaiian subjects.

We also acknowledge that the Council of Regency is our government that was lawfully established under extraordinary circumstances, and we support its effort to bring compliance with the law of occupation by the State of Hawai‘i, on behalf of the United States, which will eventually bring the American occupation to a close. When this happens, our Legislative Assembly will be brought into session so that Hawaiian subjects can elect a Regency of our choosing. The Council of Regency is currently operating in an acting capacity that is allowed under Hawaiian law.

We urge you to work with the Council of Regency in making sure this transition is not only lawful but is done for the benefit of all Hawaiian subjects. Please consider the gravity of this situation and take immediate action to establish a military government in Hawaii. Such a measure would align with international law and demonstrate a commitment to justice, fairness, and the recognition of the rights of Native Hawaiians. Thank you for your attention to this critical issue. We look forward to your prompt response and to any actions you will take to address these concerns.

The 37 names and ranks of Police Officers, that included both active and retired, is a very impressive list. The names are listed in order of rank, which includes a Police Chief, an Assistant Chief, a Deputy Chief, 2 Captains, 5 Lieutenants, 5 Detectives, 10 Sergeants, and 12 Officers. Alika Desha, a retired Honolulu Police Department Officer, signed the letter on behalf of the 36 named Police Officers. Desha was asked why did they send their letter to Major General Hara. He responded:

Having learned the truth about the illegal overthrow of Hawai‘i’s government and the continued illegal occupation of the United States in Hawai‘i has a profound impact on our Law Enforcement Officers enforcing US laws. Trying to get clarity with Corp Council on liability issues Officers face by enforcing laws of an invading country is like riding on a never ending merry go round.

There is a code of ethics that we as police officers understand that assist in guiding us throughout our life. Part of it says that it is our fundamental duty to serve mankind; to protect the innocent against deception and the weak against oppression or intimidation. An invading country thought that the truth can be hidden with cover-ups and decorations. But as time goes by, what is true is revealed, and what is fake fades away.

As Law Enforcement Officers we will continue to share the truth and fight the wrong.

The Police Departments trace their origin to May 4, 1847, when King Kamehameha III signed into law a Joint Resolution to amend “Act to Organize the Executive Departments of the of the Hawaiian Islands.” The highest ranking officer was the Marshal, who was also the Sheriff for the Island of O‘ahu. Upon the Marshal’s recommendation, the Governors of Hawai‘i Island, Maui, and Kaua‘i would appoint Sheriffs. Under the Sheriffs, the cadre of officers were called Constables.

The purpose of this blog of the Council of Regency is to provide accurate information to inform the people of Hawai‘i about the prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the steps the Council of Regency are taking to eventually bring the American occupation to an end. Misinformation will not be tolerated, especially on matters that have severe consequences for the population that resides within the occupied State of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

It has been asserted, as a comment on the recent blog article “It’s About Law—Native Hawaiian Rights are at a Critical Point for the State of Hawai‘i to Comply with the Law of Occupation,” that there is now a showdown between U.S. Army Major General Kenneth Hara’s duty to transform the State of Hawai‘i into a Military Government and the plenary power of the U.S. Congress. There exists no such thing.

The Congress is the legislative branch of the Government of the United States whose authority includes the enactment of laws and providing oversight of the executive branch. The term plenary power refers to the complete or absolute authority, which is frequently used to describe the commerce power of the Congress. Complete or absolute authority means that only the Congress has this power of enacting commercial laws.

Of the three branches of the U.S. Government—the legislative, the executive, and the judicial, only the executive branch can exercise its authority outside of U.S. territory through the Department of State and the Department of Defense. In United States v. Curtiss-Wright Corporation (1936), U.S. Supreme Court explained:

Not only, as we have shown, is the federal power over external affairs in origin and essential character different from that over internal affairs, but participation in the exercise of the power is significantly limited. In this vast external realm, with its important, complicated, delicate and manifold problems, the President alone has the power to speak or listen as a representative of the nation. He makes treaties with the advice and consent of the Senate; but he alone negotiates. Into the field of negotiation the Senate cannot intrude, and Congress itself is powerless to invade it.

On the subject of the limits of the Congress to enact laws, whether commercial laws or not, the U.S. Supreme Court, in the Curtiss-Wright case, also stated:

Neither the Constitution nor the laws passed in pursuance of it have any force in foreign territory unless in respect of our own citizens (see American Banana Co. v. United Fruit Co., 213 U. S. 347, 213 U. S. 356), and operations of the nation in such territory must be governed by treaties, international understandings and compacts, and the principles of international law.

Because the Hawaiian Kingdom is foreign territory and cannot exist within the territory of the United States, Major General Hara’s duty to transform the State of Hawai‘i into a Military Government stem from him being a part of the executive branch, the U.S. Department of Defense. The presence of the United States can only be allowed under the strict guidelines and rules of the 1907 Hague Regulations and the 1949 Fourth Geneva Convention, and not the plenary power of the Congress. The transformation into a military government will bring the United States into compliance with “treaties, international understandings and compacts, and the principles of international law.”

On April 26, 2024, the Minister of the Interior published a memorandum addressing the effects of an illegal occupation by the United States since January 17, 1893, the restoration of the Hawaiian Kingdom Government on February 28, 1997, the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s recognition of the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the Council of Regency as its government on November 8, 1999, exposure of the continuity of Hawaiian Kingdom Statehood since 2001, transforming the State of Hawai‘i into a Military Government, and the continuity of rights of Hawaiian subjects under Hawaiian Kingdom laws to land, healthcare, and fishing.

The Minister of the Interior’s purpose was to have the memorandum disseminated amongst the national population of the Hawaiian Kingdom so that they know certain rights they have under Hawaiian Kingdom law and to know the circumstances by which these rights can be exercised for their benefit. The exercising of these rights to land, healthcare, and fishing, would greatly enhance their lives and their families in Hawai‘i. Under the law of occupation, it is the responsibility of a Military Government that would ensure these rights can be exercised.

Now at 131 years of an illegal and prolonged occupation, the Hawaiian Kingdom is finally at the stage of actionable compliance with the law of occupation by the State of Hawai‘i, on behalf of the United States, setting the course to bring the American occupation to an end. This process begins when Army Major General Kenneth Hara, Director of the State of Hawai‘i Department of Defense, proclaims that the State of Hawai‘i has been transformed into a Military Government so that it will begin to administer the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom that existed prior to the occupation on January 17, 1893, and the provisional laws proclaimed by the Council of Regency in 2014, so that these nineteenth century laws can be brought up to date. The proclamation stated:

And, We do hereby proclaim that from the date of this proclamation all laws that have emanated from an unlawful legislature since the insurrection began on July 6, 1887 to the present, to include United States legislation, shall be the provisional laws of the Realm subject to ratification by the Legislative Assembly of the Hawaiian Kingdom once assembled, with the express proviso that these provisional laws do not run contrary to the express, reason and spirit of the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom prior to July 6, 1887, the international laws of occupation and international humanitarian law.

On August 1, 2023, the Minister of the Interior published a memorandum that provides the formula for determining which laws of the United States, State of Hawai‘i, and Counties, presently being imposed in the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom, shall be considered the provisional laws.

Why is this important for Native Hawaiians who comprise the majority of the national population of the Hawaiian Kingdom called Hawaiian subjects? Because the greatest dilemma facing Native Hawaiians today is not having a home and not having adequate health care. According to the Office of Hawaiian Affairs’ Native Hawaiian Health Fact Sheet 2017, “Today, Native Hawaiians are perhaps the single racial group with the highest health risk in the State of Hawai‘i. This risk stems from high economic and cultural stress, lifestyle and risk behaviors, and late or lack of access to health care.”

The cost of living under American control has placed Hawai‘i as the most expensive place in the United States to live. According to the Missouri Economic Research and Information Center in 2023, Hawai‘i has the highest cost of living in the United States with an index of 180.3. The national average index was at 100. The cost of living is calculated by combining the cost for groceries, housing, utilities, transportation, and health care. This reality forced Native Hawaiians to move to America, where they outnumber the population of Native Hawaiians in Hawai‘i. The U.S. Census report indicated that in 2020, there were a total of 680,442 Native Hawaiians, with 47 percent residing in Hawai‘i, and 53 percent residing in the United States.

The average cost of a home in Hawai‘i is $820,000.00, and health care insurance for a family of 4 is approximately at $1,500 a month. Under Hawaiian Kingdom laws, Native Hawaiians, who are called aboriginal Hawaiian subjects under Hawaiian law, are the recipients of free health care at Queen’s Hospital and at its outlets across the islands today. Aboriginal Hawaiian subjects are also able to acquire up to 50 acres of public lands at $20.00 per acre under the 1850 Kuleana Act, which has not been repealed. With the current rate of construction costs, which includes building material and labor, an aboriginal Hawaiian subject can build a 3 bedroom 1 bath home for $100,000.00, which is far less than the average cost of a home today.

Hawaiian Kingdom laws also provide for fishing rights that extend out to the first reef or where there is no reef, out to 1 mile, exclusively for all Hawaiian subjects and lawfully resident aliens of the land divisions called ahupua‘a or ‘ili, such as the ahupua‘a of Waimanalo and the ‘ili of Kuli‘ou‘ou. This is an important Hawaiian law because, since the American presence, anyone can access and deplete these resources from the exclusive rights of the residents of the ahupua‘a or ‘ili.

From the first reef or from the one nautical mile marker point out to twelve nautical miles, all Hawaiian subjects and lawfully resident aliens have exclusive access to economic activity, such as access to underwater resources and fishing. Once the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea is acceded to by the Council of Regency, this exclusive access to economic activity will extend out to 200 miles called the Exclusive Economic Zone.

The 2024-2025 State of Hawai‘i $19.2 billion budget, gives MG Hara the resources to transform the State of Hawai‘i into a Military Government by reallocating monies in line with returning to the status quo ante of the Hawaiian Kingdom and its institutions as they were prior to the American occupation. In particular, MG Hara can immediately allocate monies to the Queen’s Hospital so that Native Hawaiians have access to free healthcare that has been secured under Hawaiian Kingdom law.

Since the restoration of the Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1997, the Council of Regency has been on a track of compelling the United States and the State of Hawai‘i to comply with the international law of occupation. Its three-phase strategic plan was framed in order to achieve this objective.

Phase I—verification of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State and a subject of international law. Phase II—exposure of Hawaiian Statehood within the framework of international law and the laws of occupation as it affects the realm of politics and economics at both the international and domestic levels. Phase III—restoration of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State and a subject of international law. Phase III occurs when the American occupation comes to an end by a treaty of peace.

Critical to this strategy was to have a reputable international body recognize the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State under international law, which is phase 1. Phase 1 was not seeking international recognition of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a new State because recognition was already afforded in the nineteenth century. Rather, phase 1 was seeking the recognition of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s “continuity” as a State and its laws. The Regency knew that international law clearly provided for the Hawaiian Kingdom’s continued existence despite the illegal overthrow of its Government by the United States on January 17, 1893. What was needed, however, was to have an international body conclude, by an application of relevant international laws, that the Hawaiian State indeed “continues” to exist. Phase 1 would be a very complex legal situation to play out.

Because the State under international law is a legal entity, it needs a government to speak on its behalf no different than how a business corporation is a legal entity that needs a CEO and a Board of Directors to speak on its behalf. Without a physical body, the legal entity is silent but still legally exists. So, to get this matter before an international body, the Hawaiian Government had to first be in place in order to speak for the Hawaiian State. Another aspect to this, would be the legal competency for the Regency to be the lawful Government representing the Hawaiian State. This raises two issues, first the legal competency for the Regency to be established in accordance with Hawaiian Kingdom laws, and, second, whether the Regency needed diplomatic recognition to be the Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

Under international law, once recognition of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a sovereign and independent State was achieved in the nineteenth century, it was also the recognition of its government being a constitutional monarchy. Any successor Head of State since the original recognition of King Kamehameha III, as the Head of State, would not require diplomatic recognition so long as the successor became the Head of State in accordance with the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

The legal doctrines of recognition of new governments only arise “with extra-legal changes in government” of an existing State. Successors to King Kamehameha III were not established through “extra-legal changes,” but rather under the constitution and laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom. According to Restatement (Third) of Foreign Relations Law of the United States, “Where a new administration succeeds to power in accordance with a state’s constitutional processes, no issue of recognition or acceptance arises; continued recognition is assumed.”

Under Hawaiian law, the Council of Regency serves in the absence of the Executive Monarch. While the last Executive Monarch was Queen Lili‘uokalani, who died on November 11, 1917, the office of the Executive Monarch remained vacant under Hawaiian constitutional law. There was no legal requirement for the Council of Regency, being the successor in office to Queen Lili‘uokalani under Hawaiian constitutional law, to obtain recognition from the United States to be the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

The United States’ recognition of the Hawaiian Kingdom, as an independent State on July 6, 1844, was also a recognition of its government—a constitutional monarchy. Successors in office to King Kamehameha III, who at the time of international recognition was King of the Hawaiian Kingdom, did not require diplomatic recognition. These successors included King Kamehameha IV in 1854, King Kamehameha V in 1863, King Lunalilo in 1873, King Kalākaua in 1874, Queen Lili‘uokalani in 1891, and the Council of Regency in 1997.

If the successor arose out of a revolution, which comes about through “extra-legal changes in government,” it would need diplomatic recognition as the de facto government that replaced the previous form of government. This is why the insurgency, calling itself the provisional government, needed diplomatic recognition as a de facto government by resident U.S. Minister John Stevens on January 17, 1893, to have any semblance of legality under international law. President Grover Cleveland, after investigating the overthrow, told the Congress, by message, on December 18, 1893:

When our Minister recognized the provisional government the only basis upon which it rested was the fact that the Committee of Safety had…declared it to exist. It was neither a government de facto [in fact] nor de jure [in law]. That it was not in such possession of the Government property and agencies as entitled it to recognition.

President Cleveland also undermined the status of the provisional government when he told the Congress, “the Government of the Queen…was undisputed and both the de facto and the de jure government.” In other words, they were not a successful revolution, and that the lawful government was the Hawaiian Kingdom as a constitutional monarchy. Instead, they were an insurgency and a puppet creation by the United States. On this note, the President told the Congress that the “provisional government owes its existence to an armed invasion by the United States.”

With the government in place since 1997, the legal complexities to achieve phase I were set and it played out at the Permanent Court of Arbitration (“PCA”) in The Hague, Netherlands. The PCA was established in 1899 by the United States and twenty-five other countries as an intergovernmental organization that provides a variety of dispute resolution services to the international community. In 1907, the 1899 Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes was superseded by the 1907 Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes. Presently, there are currently 122 countries that became contracting States to either the 1899 or the 1907 Conventions, which includes the United States.

On November 8, 1999, a dispute between Lance Paul Larsen, a Hawaiian subject, and the Hawaiian Kingdom was submitted to the PCA for settlement, which came to be known as Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom. Larsen was alleging that the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom, by its Council of Regency, should be liable for allowing the unlawful imposition of American laws. He alleged that these laws denied him a fair trial, which led to his incarceration.

Before the PCA could establish an arbitration tribunal to resolve the dispute, it had to verify that the Hawaiian Kingdom “continues” to exist as a State under international law and that its government is the Council of Regency. It did, and on June 9, 2000, the PCA established the arbitration tribunal comprised of three arbitrators. With phase 1 completed, phase 2 was initiated, which began the exposure of Hawaiian Statehood during oral hearings at the PCA on December, 7, 8, and 11, 2000.

Phase 2 was continued at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, where for the past twenty-four years research, publications, and classroom instructions have begun to normalize the circumstance of the American occupation and the role of how the law of occupation will bring the American occupation to a close. This exposure phase will trigger compliance to the law of occupation by the State of Hawai‘i, but not the United States federal government.

The law of occupation obligates the entity of the occupying State, who is in effective control of a majority of the territory of the occupying State, to establish a military government to begin to administer the laws of the occupied State. When the United States occupied Japan from 1945 to 1952, General Douglas MacArthur served as the Military Governor overseeing the Japanese civilian government. The function of a military government is to provisionally administer the laws of the occupied State until there is a treaty of peace where the occupation will come to an end. When the 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty with Japan came into force on April 28, 1952, the United States occupation of Japan came to an end.

In 1893, the United States did not establish a military government and it allowed their puppet governments, called the provisional government who later changed its name to the Republic of Hawai‘i on July 4, 1894, to impose its will on the population. After illegally annexing the Hawaiian Islands on July 7, 1898, the United States unlawfully imposed its own laws over the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom through its puppets the Territory of Hawai‘i from 1900 to 1959, and the State of Hawai‘i from 1959 to the present. Under international law, all acts done by the United States are void and invalid because the United States does not have sovereignty over the Hawaiian Islands.

President Cleveland also stated to the Congress that the overthrow of the Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom was directly tied to an incident of war. He stated that by “an act of war, committed with the participation of a diplomatic representative of the United States and without authority of Congress, the Government of a feeble but friendly and confiding people has been overthrown.” The overthrow of the Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom did not affect the sovereignty and legal order of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State. U.S. Army Field Manual 27-10 regulates the actions taken by U.S. troops during the military occupation of a foreign State. Paragraph 358 states:

Being an incident of war, military occupation confers upon the invading force the means of exercising control for the period of occupation. It does not transfer the sovereignty to the occupant, but simply the authority or power to exercise some of the rights of sovereignty. The exercise of these rights results from the established power of the occupant and from the necessity of maintaining law and order, indispensable both to the inhabitants and to the occupying force. It is therefore unlawful for a belligerent occupant to annex occupied territory or to create a new State therein while hostilities are still in progress.

Only the Hawaiian Kingdom has sovereignty over the Hawaiian Islands and not the United States. International law does not allow two sovereignties to exist within one and the same State. In the S.S. Lotus case, which was a dispute between France and Turkey, the Permanent Court of International Justice explained:

Now the first and foremost restriction imposed by international law upon a State is that—failing the existence of a permissive rule to the contrary—it may not exercise its power in any form in the territory of another State. In this sense jurisdiction is certainly territorial; it cannot be exercised by a State outside its territory except by virtue of a permissive rule derived from international custom or from a convention (treaty).

The permissive rule under international law that allows one State to exercise authority over the territory of another State is Article 43 of the 1907 Hague Regulations and Article 64 of the 1949 Geneva Convention, that mandates the occupant to establish a military government to provisionally administer the laws of the occupied State until there is a treaty of peace. For the past 131 years, there has been no permissive rule of international law that allows the United States to exercise any authority in the Hawaiian Kingdom. Instead, it imposed its will over the population of the Hawaiian Kingdom by unlawfully imposing its laws, which was at the center of the Larsen case. The PCA described the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom arbitration case on its website as:

Lance Paul Larsen, a resident of Hawaii, brought a claim against the Hawaiian Kingdom by its Council of Regency (“Hawaiian Kingdom”) on the grounds that the Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom is in continual violation of: (a) its 1849 Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation with the United States of America, as well as the principles of international law laid down in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 1969 and (b) the principles of international comity, for allowing the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws over the claimant’s person within the territorial jurisdiction of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

To bring compliance with the law of occupation and to allow the presence of the United States, by virtue of the permissive rule embodied in the 1907 Hague Regulations and the 1949 Geneva Convention, the State of Hawai‘i must be transformed into a Military Government. The determining factor as to what entity of the United States has the duty to become a Military Government is the “effectiveness” test. Article 42 of the 1907 Hague Regulations clearly states, “Territory is considered occupied when it is actually placed under the authority of the hostile army. The occupation extends only to the territory where such authority has been established and can be exercised.” In other words, an entity cannot enforce the laws of the occupied State without being in effective control of the territory of the occupied State.

In this situation, it is the State of Hawai‘i and not the federal government that is in effective control of the majority of Hawaiian Kingdom territory, where the latter is only in effective control of less then 500 square miles while the former is in effective control of 10,931 square miles.

The officer of the State of Hawai‘i that has the duty to transform the State of Hawai‘i into a Military Government is the Director of the State of Hawai‘i Department of Defense U.S. Army Major General Kenneth Hara. Governor Josh Green is a civilian, and he has no direct link to the United States Department of Defense whose Directive no. 5100.01 explicitly states that one of the functions of the Army in “[occupied] territories abroad [is to] provide for the establishment of a military government pending transfer of this responsibility to other authority.”

Like General MacArthur, MG Hara would serve as the Military Governor. His actions, though, are constrained by international law and the law of occupation. International law also provides for the sharing of authority between the Military Governor and the Council of Regency. MG Hara does not have absolute authority. On this topic of shared authority, Professor Federico Lenzerini, in his legal opinion, explains:

Despite the fact that the occupation inherently configures as a situation unilaterally imposed by the occupying power—any kind of consent of the ousted government being totally absent—there still is some space for “cooperation” between the occupying and the occupied government—in the specific case of Hawai’i between the State of Hawai‘i and its Counties and the Council of Regency. Before trying to specify the characteristics of such a cooperation, it is however important to reiterate that, under international humanitarian law, the last word concerning any acts relating to the administration of the occupied territory is with the occupying power. In other words, “occupation law would allow for a vertical, but not a horizontal, sharing of authority […] [in the sense that] this power sharing should not affect the ultimate authority of the occupier over the occupied territory”. This vertical sharing of authority would reflect “the hierarchical relationship between the occupying power and the local authorities, the former maintaining a form of control over the latter through a top-down approach in the allocation of responsibilities”.

The Council of Regency has provided MG Hara an Operational Plan, with essential and implied tasks, to transform the State of Hawai‘i into a Military Government.

While the State of Hawai‘i has yet to transform itself into a Military Government and proclaim the provisional laws proclaimed by the Council of Regency, Hawaiian Kingdom laws as they were prior to January 17, 1893, continue to exist. Because of phase 2 there is a growing awareness among Native Hawaiians on not only the circumstances of the American occupation but also the denial of their rights secured under Hawaiian Kingdom law, which the American presence took away from them and their families.

MG Hara’s delay in proclaiming the establishment of the Military Government of Hawai‘i has now a direct impact on the rights of Native Hawaiian families and their ability to exercise and benefit from these rights under Hawaiian Kingdom law. According to international law, the enforcement of the law of occupation is with MG Hara, but the pressure placed upon MG Hara to enforce Hawaiian Kingdom laws are with Native Hawaiians whose rights are being denied by his inaction. In other words, MG Hara’s reluctance to carry out his duty can now be directly tied to Native Hawaiians lack of a home and adequate healthcare.

In 2011, Dr. Keanu Sai wrote a book titled Ua Mau Ke Ea – Sovereignty Endures: An Overview of the Political and Legal History of the Hawaiian Islands. Pū‘ā Foundation is the publisher of this book that can be purchased online at their website. This book draws from Dr. Sai’s doctoral dissertation in political science titled The American Occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom: Beginning the Transition from Occupied to Restored State. Ua Mau is currently being used to teach Hawaiian history in the Middle Schools, High Schools, and entry level collage classes.

In 2020, Dr. Sai is an editor and author of a free eBook titled Royal Commission of Inquiry: Investigating War Crimes and Human Rights Violations Committed in the Hawaiian Kingdom. Contributing authors include Professor Matthew Craven from the University of London, SOAS, Law Department, on the subject of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s continued existence as a State under international law; Professor William Schabas from Middlesex University London, Law Department, on the subject of war crimes being committed in the Hawaiian Kingdom; and Professor Federico Lenzerini from the University of Siena, Italy, Department of Political and International Science, on the subject of human rights violations committed in the Hawaiian Kingdom and the right of self-determination of a population under military occupation. In 2022, a book review of the Royal Commission of Inquiry’s eBook was done by Dr. Anita Budziszewska from the University of Warsaw, which was published in the Polish Journal of Political Science. This book is currently being used in undergraduate and graduate courses at universities.

To access Dr. Sai’s other publications you can visit his University of Hawai‘i website. Dr. Sai firmly believes in the power of education. He often states, “The practical value of history, is that it is a film of the past, run through the projector of today, on to the screen of tomorrow.” It is through education and awareness that the national consciousness of the Hawaiian Kingdom will be restored to its rightful place.

When the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom was restored in 1997 by a Council of Regency, it came into existence where the population of the Hawaiian Islands effectively had their national consciousness of the Hawaiian Kingdom from the nineteenth century obliterated and replaced with an American national consciousness. The process by which this obliteration occurred was by a deliberate and consistent policy of denationalization through Americanization that was formally instituted in the public and private school system in 1906 by the Department of Public Instruction, which is currently called the Department of Education.

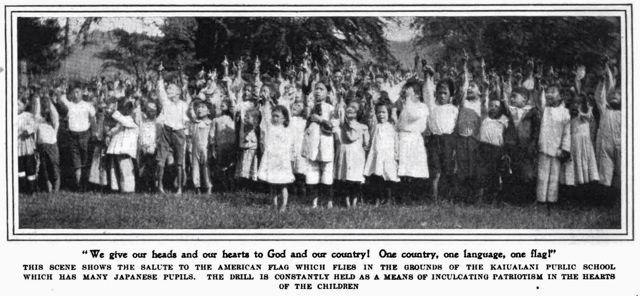

According to the Programme, “The teacher will call one of the pupils to come forward and stand at one side of the desk while the teacher stands at the other. The pupil shall hold an American flag in military style. At second signal all children shall rise, stand erect and salute the flag, concluding with the salutation, ‘We give our heads and our hearts to God and our Country! One Country! One Language! One flag!’”

In 1907, Harper’s Weekly magazine covered the Americanization taking place at Ka‘ahumanu and Ka‘iulani Public Schools, which has students from the first to eighth grade. When the reporter visited Ka‘iulani Public School, he documented the policy being carried out and took a picture of the 614 school children saluting the American flag. He wrote:

At the suggestion of Mr. Babbitt, the principal, Mrs. Fraser, gave an order, and within ten seconds all of the 614 pupils of the school began to march out upon the great green lawn which surrounds the building. Hawaii differs from all our other tropical neighbors in the fact that grass will grow here. To see beautiful, velvety turf amid groves of palms and banana trees and banks of gorgeous scarlet flowers gives a feeling of sumptuousness one cannot find elsewhere.

Out upon the lawn marched the children, two by two, just as precise and orderly as you can find them at home. With the ease that comes of long practice the classes marched and countermarched until all were drawn up in a compact array facing a large American flag that was dancing in the northeast trade-wind forty feet above their heads. Surely this was the most curious, most diverse regiment ever drawn up under that banner—tiny Hawaiians, Americans, Britons, Germans, Portuguese, Scandinavians, Japanese, Chinese, Porto-Ricans, and Heaven knows what else.

‘Attention!’ Mrs. Fraser commanded.

The little regiment stood fast, arms at sides, shoulders back, chests out, heads up, and every eye fixed upon the red, white, and blue emblem that waved protectingly over them.

‘Salute!’ was the principal’s next command.

Every right hand was raised, forefinger extended, and the six hundred and fourteen fresh, childish voices chanted as one voice:

‘We give our heads and our hearts to God and our Country! One Country! One Language! One Flag!’