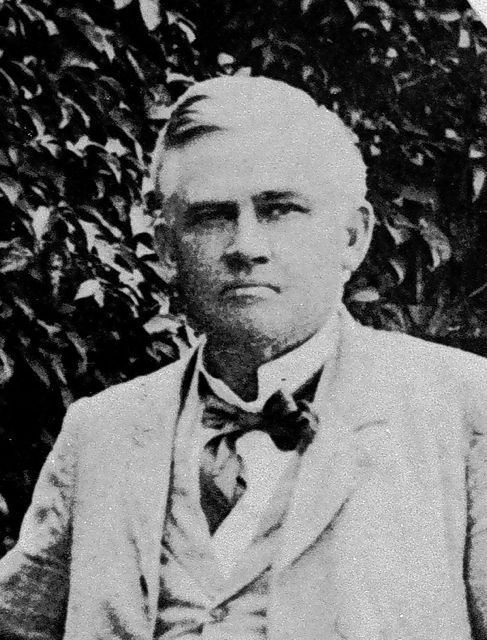

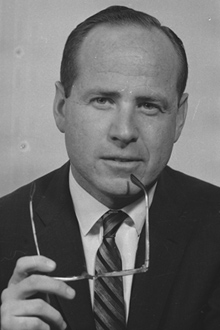

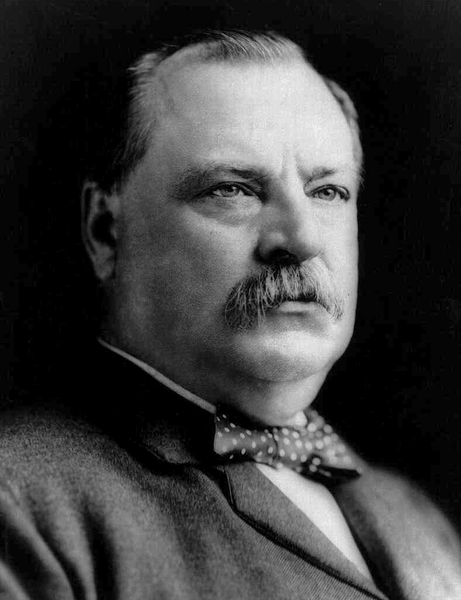

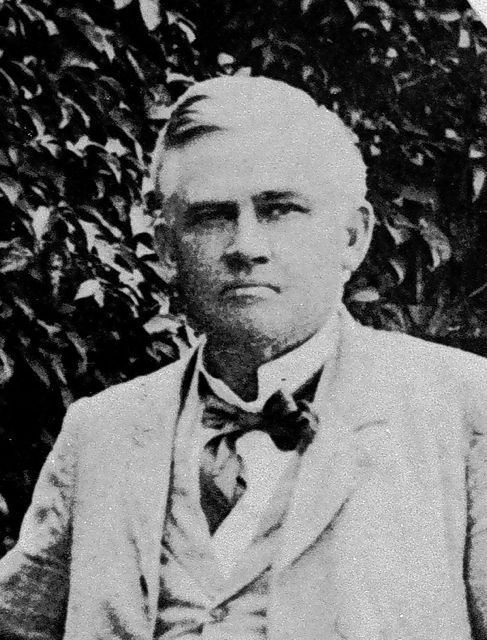

James Blount, who served by appointment of U.S. President Grover Cleveland as a Special Commissioner to investigate the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government on January 17, 1893, began his investigation in the Hawaiian Islands on April 1. For the next four months Special Commissioner Blount would submit periodic reports to U.S. Secretary of State Walter Gresham in Washington, D.C., which came to be known as the “Blount Reports.” On July 17, 1893, Blount submitted his final report. It was from these reports that Secretary of State Gresham would conclude the investigation and notify the President on October 18, 1893 that “should not the great wrong done to a feeble but independent State by an abuse of the authority of the United States be undone by restoring the legitimate government? Anything short of that will not, I respectfully submit, satisfy the demands of justice.” Here follows a portion of the final report of July 17, 1893 that centers on the insurgents calling themselves the “Committee of Safety” and at the end identifies their nationalities (citizenry).

James Blount, who served by appointment of U.S. President Grover Cleveland as a Special Commissioner to investigate the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government on January 17, 1893, began his investigation in the Hawaiian Islands on April 1. For the next four months Special Commissioner Blount would submit periodic reports to U.S. Secretary of State Walter Gresham in Washington, D.C., which came to be known as the “Blount Reports.” On July 17, 1893, Blount submitted his final report. It was from these reports that Secretary of State Gresham would conclude the investigation and notify the President on October 18, 1893 that “should not the great wrong done to a feeble but independent State by an abuse of the authority of the United States be undone by restoring the legitimate government? Anything short of that will not, I respectfully submit, satisfy the demands of justice.” Here follows a portion of the final report of July 17, 1893 that centers on the insurgents calling themselves the “Committee of Safety” and at the end identifies their nationalities (citizenry).

**************************************************************

Special Commissioner James Blount reported:

Nearly all of the arms on the island of Oahu, in which Honolulu is situated, were in the possession of the Queen’s government. A military force, organized and drilled, occupied the station house, the barracks, and the palace—the only points of any strategic significance in the event of a conflict.

The great body of the people moved in their usual course. Women and children passed to and fro through the streets, seemingly unconscious of any impending danger, and yet there were secret conferences held by a small body of men, some of whom were Germans, some Americans, and some native-born subjects of foreign origin.

On Saturday evening, the 14th of January, they took up the subject of dethroning the Queen and proclaiming a new Government with a view of annexation to the United States.

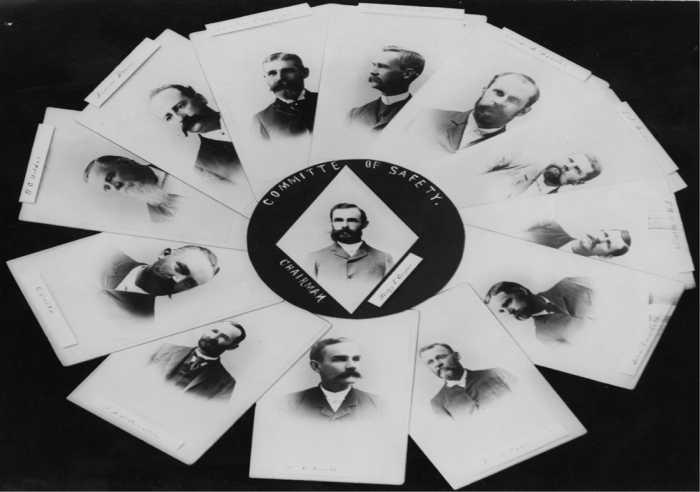

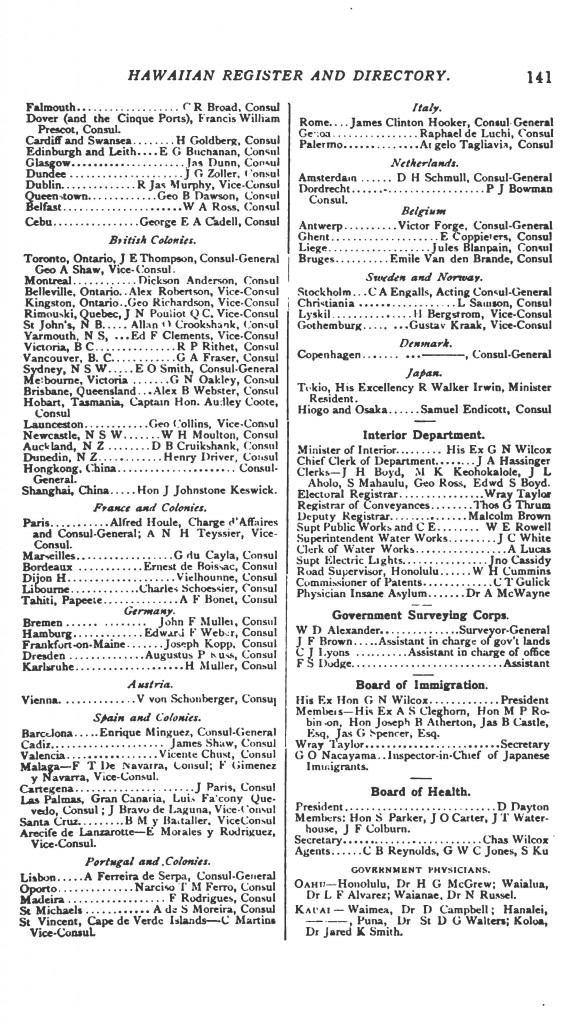

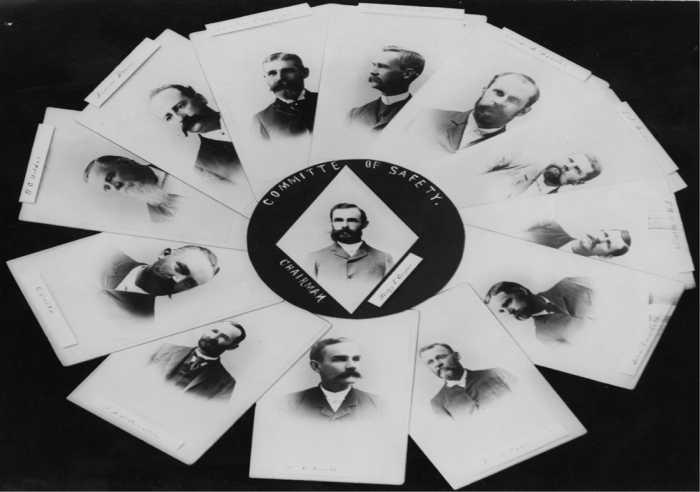

The first and most momentous question with them was to devise some plan to have the United States troops landed. Mr. Thurston, who appears to have been the leading spirit, on Sunday sought two members of the Queen’s cabinet and urged them to head a movement against the Queen, and to ask Minister Stevens to land the troops, assuring them that in such an event Mr. Stevens would do so. Failing to enlist any of the Queen’s cabinet in the cause, it was necessary to devise some other mode to accomplish this purpose. A committee of safety, consisting of thirteen members, had been formed from a little body of men assembled in W. O. Smith’s office. A deputation of these, informing Mr. Stevens of their plans, arranged with him to land the troops if they would ask it “for the purpose of protecting life and property.” It was further agreed between him and them that in the event they should occupy the government building and proclaim a new government he would recognize it. The two leading members of the committee, Messrs. Thurston and Smith, growing uneasy as to the safety of their persons, went to him to know if he would protect them in the event of their arrest by the authorities, to which he gave his assent.

At the mass meeting, called by the committee of safety on the 16th of January, there was no communication to the crowd of any purpose to dethrone the Queen or to change the form of government, but only to authorize the committee to take steps to prevent a consummation of the Queen’s purposes and to have guarantees of public safety. The committee on public safety had kept their purposes from the public view at this mass meeting and at their small gatherings for fear of proceedings against them by the government of the Queen.

After the mass meeting had closed a call on the American minister for troops was made in the following terms, and signed indiscriminately by Germans, by Americans, and by Hawaiian subjects of foreign extraction:

Hawaiian Islands,

Honolulu, January 16, 1395.

To His Excellency John L. Stevens,

American Minister Resident:

SIR: We, the undersigned, citizens and residents of Honolulu, respectfully represent that, in view of recent public events in this Kingdom, culminating in the revolutionary acts of Queen Liliuokalani on Saturday last, the public safety is menaced and lives and property are in peril, and we appeal to you and the United States forces at your command for assistance.

The Queen, with the aid of armed force and accompanied by threats of violence and bloodshed from those with whom she was acting, attempted to proclaim a new constitution; and while prevented for the time from accomplishing her object, declared publicly that she would only defer her action.

This conduct and action was upon an occasion and under circumstances which have created general alarm and terror.

We are unable to protect ourselves without aid, and, therefore, pray for the protection of the United States forces.

Henry B. Cooper,

P.W. McChesney,

W.C. Wilder,

C. Bolte,

A. Brown,

William O. Smith,

Henry Waterhouse,

Theo. F. Lansing,

Ed. Suhr,

L. A. Thurston,

John Emmeluth,

Wm. B. Castle,

J.A. McCandless,

Citizen’s Committee of Safety.

The response to that call does not appear in the files or on the records of the American legation. It, therefore, can not speak for itself. The request of the committee of safety was, however, consented to by the American minister. The troops were landed.

On that very night the committee assembled at the house of Henry Waterhouse, one of its members, living the next door to Mr. Stevens, and finally determined on the dethronement of the Queen; selected its officers, civil and military, and adjourned to meet the next morning.

Col. J. H. Soper, an American citizen, was selected to command the military forces. At this Waterhouse meeting it was assented to by all that Mr. Stevens had agreed with the committee of safety that in the event it occupied the Government building and proclaimed a Provisional Government he would recognize it as a de facto government.

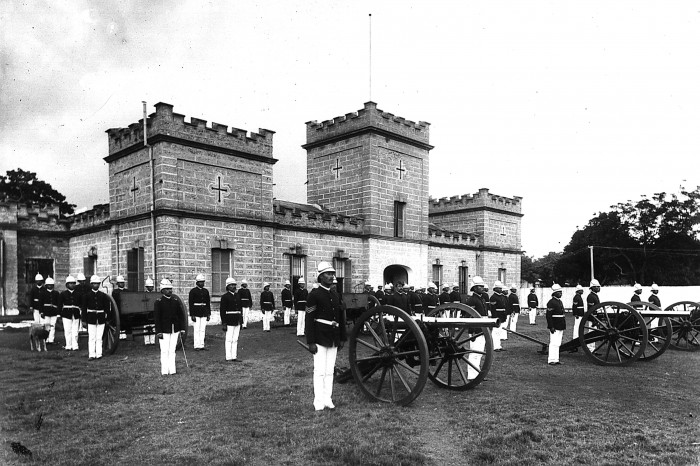

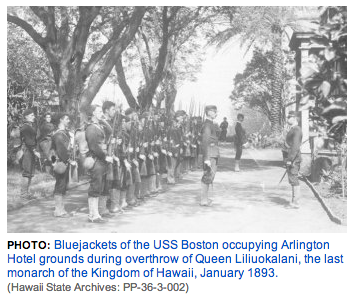

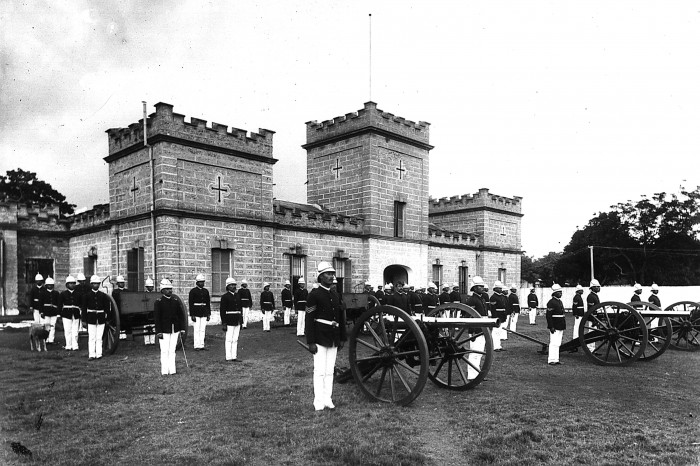

When the troops were landed on Monday evening, January 16, about 5 o’clock, and began their march through the streets with their small arms, artillery, etc., a great surprise burst upon the community. To but few was it understood. Not much time elapsed before it was given out by members of the committee of safety that they were designed to support them. At the palace, with the cabinet, amongst the leaders of the Queen’s military forces, and the great body of the people who were loyal to the Queen, the apprehension came that it was a movement hostile to the existing Government. Protests were filed by the minister of foreign affairs and by the governor of the island against the landing of the troops.

Messrs. Parker and Peterson testify that on Tuesday at 1 o’clock they called on Mr. Stevens, and by him were informed that in the event the Queen’s forces assailed the insurrectionary forces he would intervene.

At 2:30 o’clock of the same day the members of the Provisional Government proceeded to the Government building in squads and read their proclamation. They had separated in their in march to the Government building for fear of observation and arrest. There was no sign of an insurrectionary soldier on the street. The committee of safety sent to the Government building a Mr. A. S. Wilcox to see who was there and on being informed that there were no Government forces on the grounds proceeded in the manner I have related and read; their proclamation. Just before concluding the reading of this instrument fifteen volunteer troops appeared. Within a half hour afterward some thirty or forty made their appearance.

A part of the Queen’s forces, numbering 224, were located at the station house, about one-third of a mile from the Government building. The Queen, with a body of 50 troops, was located at the palace, north of the Government building about 400 yards. A little northeast of the palace and some 200 yards from it, at the barracks, was another body of 272 troops. These forces had 14 pieces of artillery, 386 rifles, and 16 revolvers. West of the Government building and across a narrow street were posted Capt. Wiltse and his troops, these likewise having artillery and small-arms.

The Government building is in a quadrangular-shaped piece of ground surrounded by streets. The American troops were so posted as to be in front of any movement of troops which should approach the Government building on three sides, the fourth being occupied by themselves. Any attack on the Government building from the east side would expose the American troops to the direct fire of the attacking force. Any movement of troops from the palace toward the Government building in the event of a conflict between the military forces would have exposed them to the fire of the Queen’s troops. In fact, it would have been impossible for a struggle between the Queen’s forces and the forces of the committee of safety to have taken place without exposing them to the shots of the Queen’s forces. To use the language of Admiral Skerrett, the American troops were well located if designed to promote the movement for the Provisional Government and very improperly located if only intended to protect American citizens in person and property.

They were doubtless so located to suggest to the Queen and her counselors that they were in cooperation with the insurrectionary movement, and would when the emergency arose manifest it by active support.

It did doubtless suggest to the men who read the proclamation that they were having the support of the American minister and naval commander and were safe from personal harm.

Why had the American minister located the troops in such a situation and then assured the members of the committee of safety that on their occupation of the Government building he would recognize it as a government de facto, and as such give it support? Why was the Government building designated to them as the place which, when their proclamation was announced therefrom, would be followed by his recognition. It was not a point of any strategic consequence. It did not involve the employment of a single soldier.

A building was chosen where there were no troops stationed, where there was no struggle to be made to obtain access, with an American force immediately contiguous, with the mass of the population impressed with its unfriendly attitude. Aye, more than this—before any demand for surrender had even been made on the Queen or on the commander or any officer of any of her military forces at any of the points where her troops were located, the American minister had recognized the Provisional Government and was ready to give it the support of the United States troops!

Mr. Damon, the vice-president of the Provisional Government and a member of the advisory council, first went to the station house, which was in command of Marshal Wilson. The cabinet was there located. The vice-president importuned the cabinet and the military commander to yield up the military forces on the ground that the American minister had recognized the Provisional Government and that there ought to be no blood shed.

After considerable conference between Mr. Damon and the ministers he and they went to the government building.

The cabinet then and there was prevailed upon to go with the vice-president and some other friends to the Queen and urge her to acquiesce in the situation. It was pressed upon her by the ministers and other persons at that conference that it was useless for her to make any contest, because it was one with the United States; that she could file her protest against what had taken place and would be entitled to a hearing in the city of Washington. After consideration of more than an hour she finally concluded, under the advice of her cabinet and friends, to order the delivery up of her military forces to the Provisional Government under protest. That paper is in the following form:

I, Liliuokalani, by the grace of God and under the constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Queen, do hereby solemnly protest against any and all acts done against myself and the constitutional Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom by certain persons claiming to have established a provisional government of and for this Kingdom.

That I yield to the superior force of the United States of America, whose minister plenipotentiary, His Excellency John L. Stevens, has caused United States troops to be landed at Honolulu and declared that he would support the said provisional government.

Now, to avoid any collision of armed forces and perhaps the loss of life, I do, under this protest, and impelled by said force, yield my authority until such time as the Government of the United States shall, upon the facts being presented to it, undo the action of its representatives and reinstate me in the authority which I claim as the constitutional sovereign of the Hawaiian Islands.

Done at Honolulu this 17th day of January, A. D. 1893.

Liliuokalani R.

Samuel Parker,

Minister of Foreign Affairs.

Wm H. Cornwell,

Minister of finance.

Jno. F. Colburn,

Minister of the Interior.

A.P. Peterson,

Attorney- General.

All this was accomplished without the firing of a gun, without a demand for surrender on the part of the insurrectionary forces until they had been converted into a de facto government by the recognition of the American minister with American troops, then ready to interfere in the event of an attack.

In pursuance of a prearranged plan, the Government thus established hastened off commissioners to Washington to make a treaty for the purpose of annexing the Hawaiian Islands to the United States.

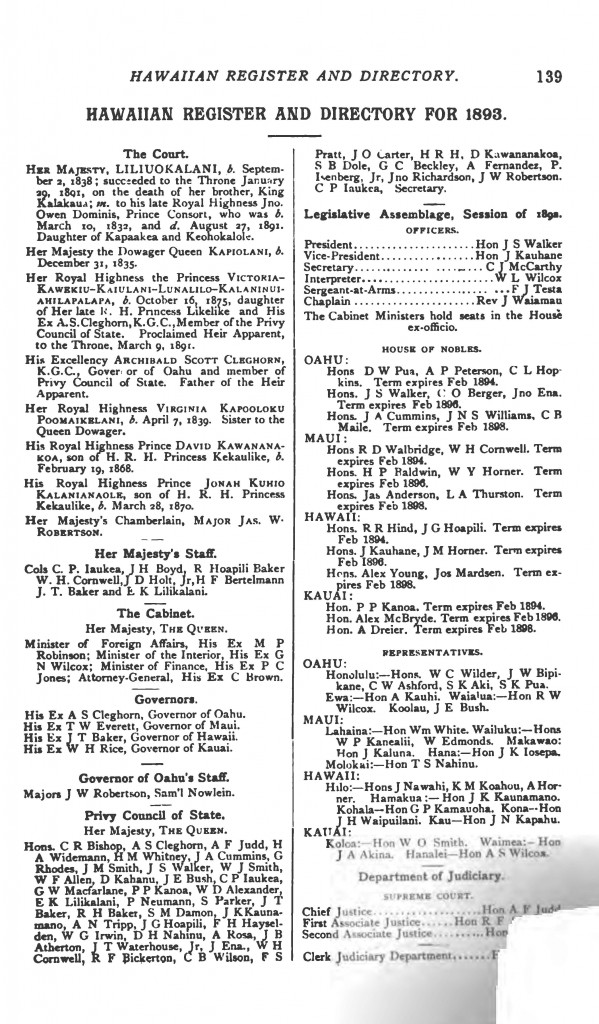

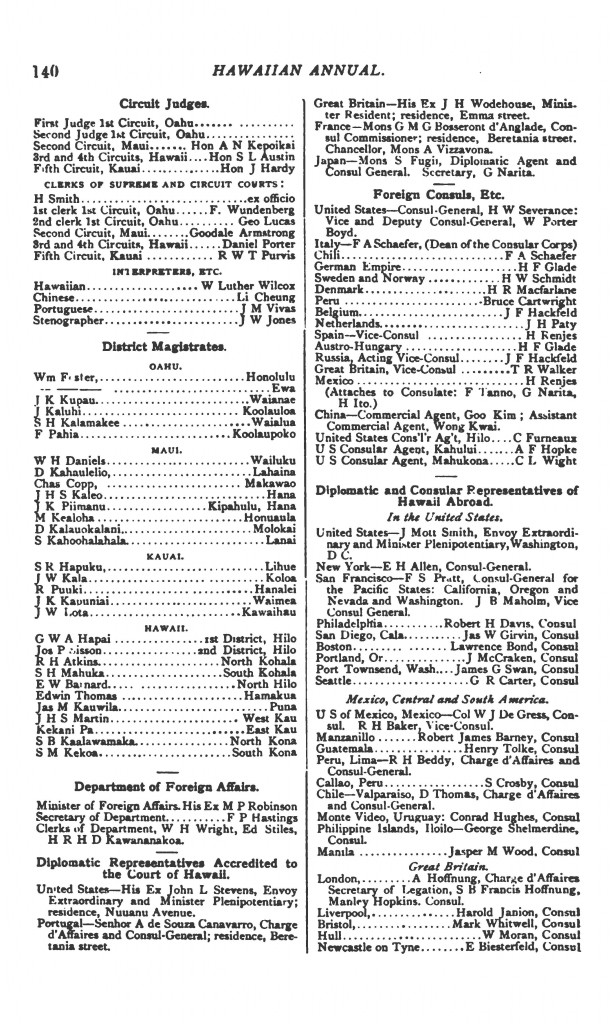

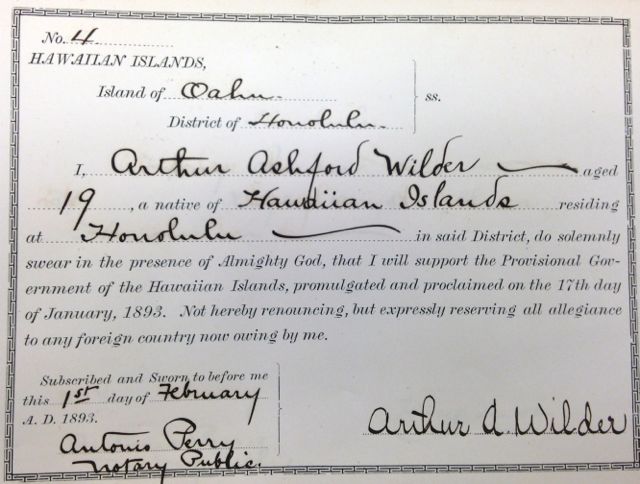

During the progress of the movement the committee of safety, alarmed at the fact that the insurrectionists had no troops and no organization, dispatched to Mr. Stevens three persons, to wit, Messrs. L. A. Thurston, W. C. Wilder, and H. F. Glade, “to inform him of the situation and ascertain from him what if any protection or assistance could be afforded by the United States forces for the protection of life and property, the unanimous sentiment and feeling being that life and property were in danger.” Mr. Thurston is a native-born subject; Mr. Wilder is of American origin, but has absolved his allegiance to the United States and is a naturalized subject; Mr. Glade is a German subject.

The declaration as to the purposes of the Queen contained in the formal request for the appointment of a committee of safety in view of the facts which have been recited, to wit, the action of the Queen and her cabinet, the action of the Royalist mass meeting, and the peaceful movement of her followers, indicating assurances of their abandonment, seem strained in so far as any situation then requiring the landing of troops might exact.

The request was made, too, by men avowedly intending to overthrow the existing government and substitute a provisional government therefor, and who, with such purpose in progress of being effected, could not proceed therewith, but fearing arrest and imprisonment and without any thought of abandoning that purpose, sought the aid of the American troops in this situation to prevent any harm to their persons and property. To consent to an application for such a purpose without any suggestion dissuading the applicants from it on the part of the American minister, with naval forces under his command, could not otherwise be construed than as complicity with their plans.

The committee, to use their own language, say: “We are unable to protect ourselves without aid, and, therefore, pray for the protection of the United States forces.”

In less than thirty hours the petitioners have overturned the throne, established a new government, and obtained the recognition of foreign powers.

Let us see whether any of these petitioners are American citizens, and if so whether they were entitled to protection, and if entitled to protection at this point whether or not subsequently thereto their conduct was such as could be sanctioned as proper on the part of American citizens in a foreign country.

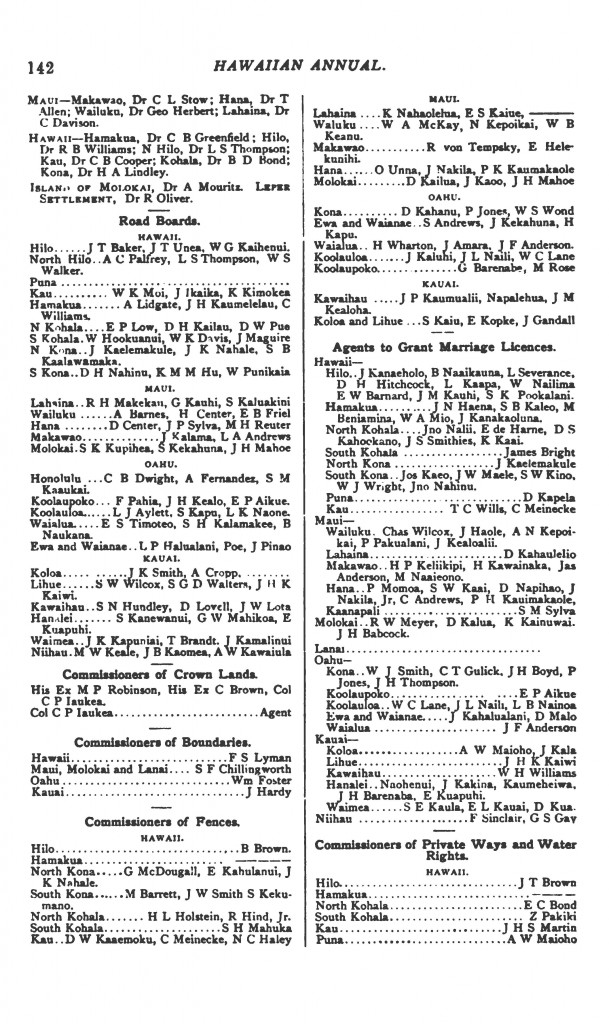

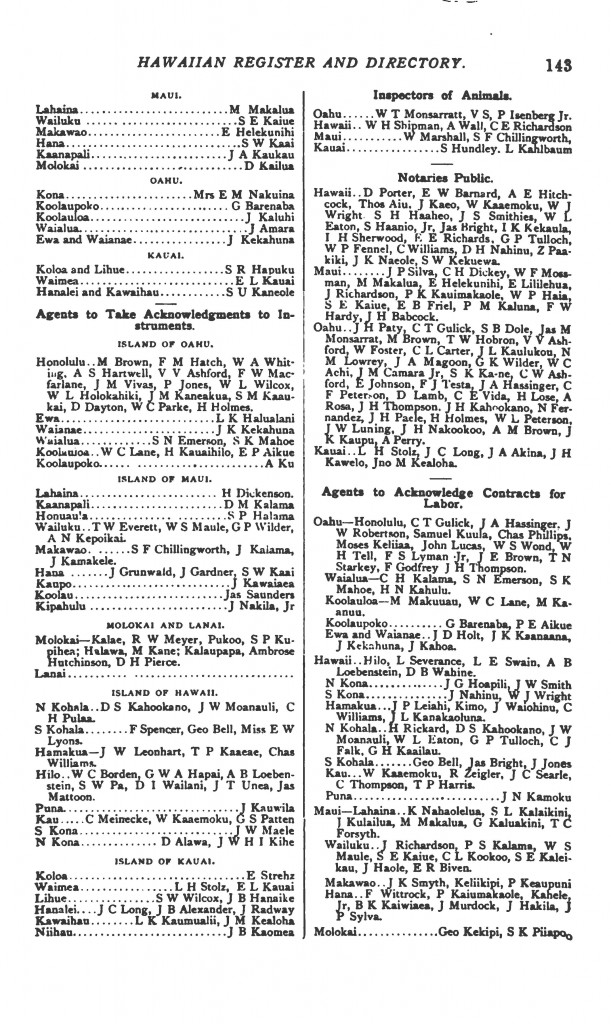

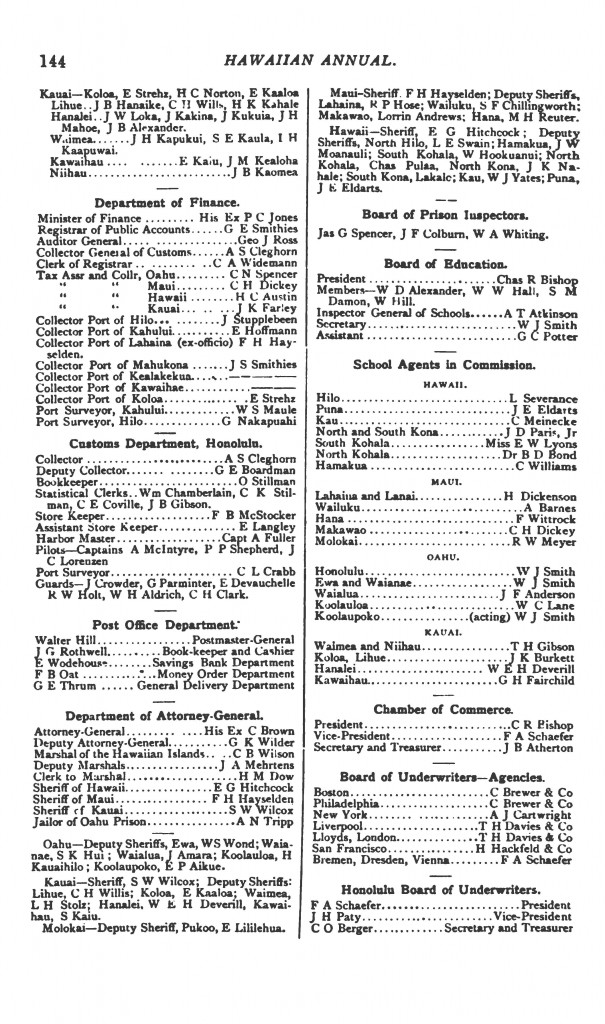

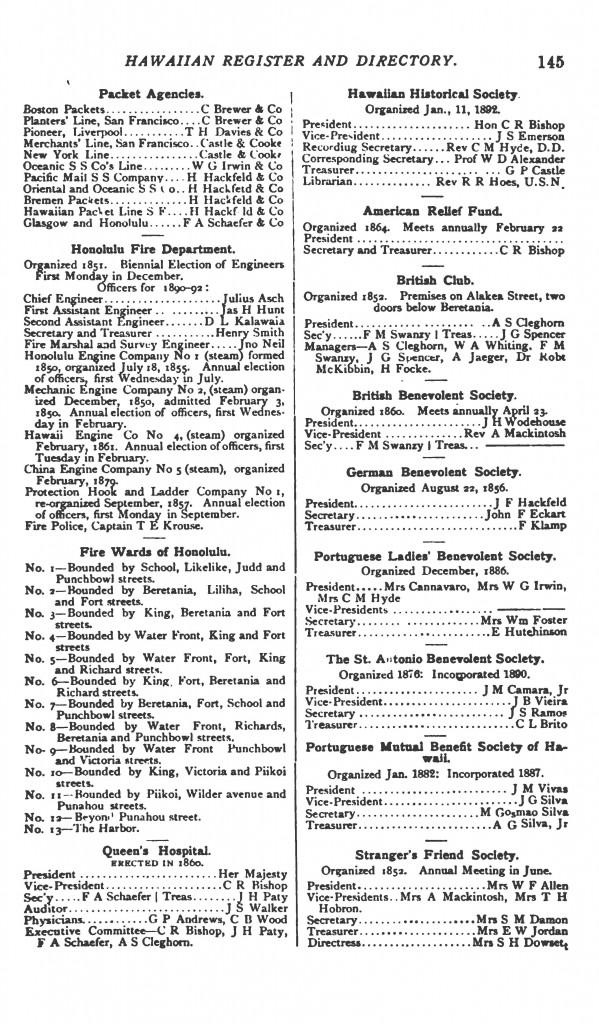

Mr. Henry E. Cooper is an American citizen; was a member of the committee of safety; was a participant from the beginning in their schemes to overthrow the Queen, establish a Provisional Government, and visited Capt. Wiltse’s vessel, with a view of securing the aid of American troops, and made an encouraging report thereon. He, an American citizen, read the proclamation dethroning the Queen and establishing the Provisional Government.

Mr. Henry E. Cooper is an American citizen; was a member of the committee of safety; was a participant from the beginning in their schemes to overthrow the Queen, establish a Provisional Government, and visited Capt. Wiltse’s vessel, with a view of securing the aid of American troops, and made an encouraging report thereon. He, an American citizen, read the proclamation dethroning the Queen and establishing the Provisional Government.

Mr. F. W. McChesney is an American citizen; was cooperating in the revolutionary movement, and had been a member of the advisory council from its inception.

Mr. W. C. Wilder is a naturalized citizen of the Hawaiian Islands, owing no allegiance to any other country. He was one of the original members of the advisory council, and one of the orators in the mass meeting on the morning of January 16.

Mr. C. Bolte is of German origin, but a regularly naturalized citizen of the Hawaiian Islands.

Mr. A. Brown is a Scotchman and has never been naturalized.

Mr. W. O. Smith is a native of foreign origin and a subject of the Islands.

Mr. Henry Waterhouse, originally from Tasmania, is a naturalized citizen of the islands.

Mr. Theo. F. Lansing is a citizen of the United States, owing and claiming allegiance thereto. He has never been naturalized in this country.

Mr. Ed. Suhr is a German subject.

Mr. L. A. Thurston is a native-born subject of the Hawaiian Islands, of foreign origin.

Mr. John Emmeluth is an American citizen.

Mr. W. it Castle is a Hawaiian of foreign parentage.

Mr. J. A. McCandless is a citizen of the United States—never having been naturalized here.

Six are Hawaiians subjects; five are American citizens; one English, and one German. A majority are foreign subjects.

It will be observed that they sign as “Citizens’ committee of safety.”

This is the first time American troops were ever landed on these islands at the instance of a committee of safety without notice to the existing government.

It is to be observed that they claim to be a citizens’ committee of safety and that they are not simply applicants for the protection of the property and lives of American citizens.

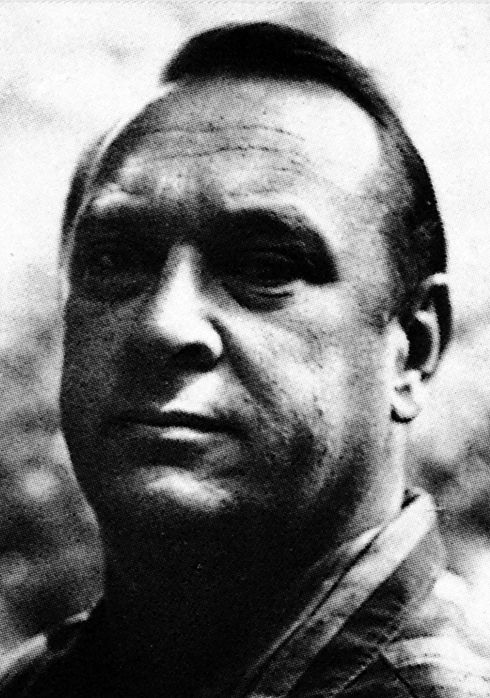

The chief actors in this movement were Messrs. L. A. Thurston and W.O. Smith.