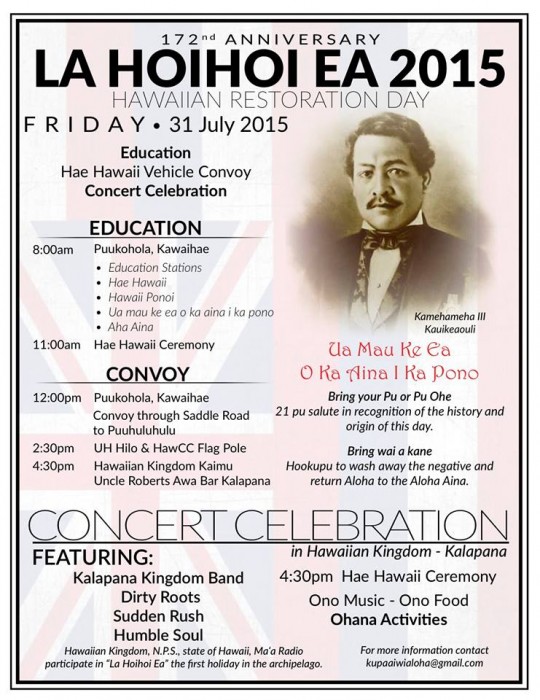

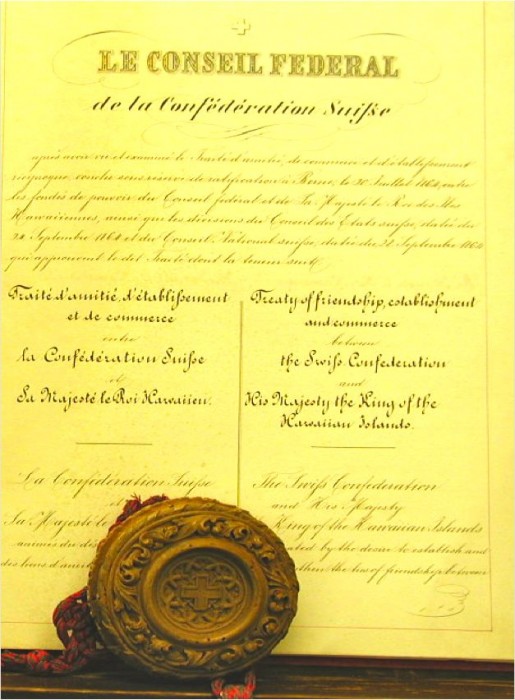

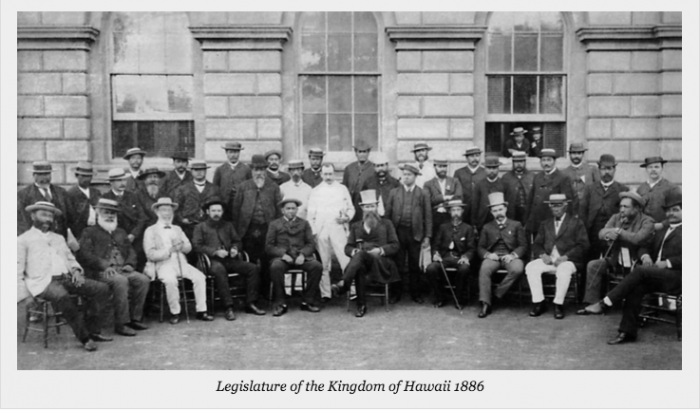

In 2001, the Permanent Court of Arbitration acknowledged that, “in the nineteenth century the Hawaiian Kingdom existed as an independent State recognized as such by the United States of America, the United Kingdom and various other States, including by exchanges of diplomatic or consular representatives and the conclusion of treaties (Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, 119 Int’l L. Rep. 566, 581 (2001).” As an independent state, the Hawaiian Kingdom was a subject of international law, which prohibited intervention in its domestic affairs by other states. According to Brownlie,

In 2001, the Permanent Court of Arbitration acknowledged that, “in the nineteenth century the Hawaiian Kingdom existed as an independent State recognized as such by the United States of America, the United Kingdom and various other States, including by exchanges of diplomatic or consular representatives and the conclusion of treaties (Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, 119 Int’l L. Rep. 566, 581 (2001).” As an independent state, the Hawaiian Kingdom was a subject of international law, which prohibited intervention in its domestic affairs by other states. According to Brownlie,

“The principal corollaries of the sovereignty and equality of states are: (1) a jurisdiction, prima facie exclusive, over a territory and the permanent population living there; (2) a duty of non-intervention in the area of exclusive jurisdiction of other states; and (3) the dependence of obligations arising from customary law and treaties on the consent of the obligor (Ian Brownlie, Principles of Public International Law 287 (4th ed. 1990).”

Should a state seek to merge into another state, international law only allows it through cession. “Cession of State territory is the transfer of sovereignty over State territory by the owner-State to another State (L. Oppenheim, International Law, vol. 1, 499 (7th ed. 1948),” says Oppenheim. “The only form in which a cession can be effected is an agreement embodied in a treaty between the ceding and the acquiring State. Such treaty may be the outcome of peaceable negotiations or of war (Id., at 500).” Through peaceful negotiations, the United States acquired by treaty, the former territories of the French in Louisiana in 1803 (8 U.S. Stat. 200), the Spanish in Florida in 1819 (8 U.S. Stat. 252), the British in Oregon in 1846 (9 U.S. Stat. 869), the Russian in Alaska in 1867 (15 U.S. Stat. 539), and the Danish in the Virgin Islands in 1916 (39 U.S. Stat. 1706). The United States acquired, through treaties of conquest, the former territories of the British in the Americas in 1783 (8 U.S. Stat. 80), the Mexicans in territory north of the Rio Grande in 1848, which includes Texas (9 U.S. Stat. 922), and the Spanish in the Philippines, Guam and Puerto Rico in 1898 (30 U.S. Stat. 1754). Hawai‘i is the only territory the United States claims without a treaty.

International law also distinguishes between the state and its government, where the latter is the physical manifestation that exercises the sovereignty of the former. Hoffman emphasizes that a government “is not a State any more than man’s words are the man himself,” but “is simply an expression of the State, an agent for putting into execution the will of the State (Frank Sargent Hoffman, The Sphere of the State or the People as a Body-Politic 19 (1894).” Wright also concluded, “international law distinguishes between a government and the state it governs (Quincy Wright, The Status of Germany and the Peace Proclamation, 46(2) Am. J. Int’l L. 299, 307 (Apr. 1952).” Therefore, a sovereign State would continue to exist despite its government being overthrown by military force. “There is a presumption that the State continues to exist, with its rights and obligations…despite a period in which there is no, or no effective, government,” explains Crawford. “Belligerent occupation does not affect the continuity of the State, even where there exists no government claiming to represent the occupied State (James Crawford, The Creation of States in International Law 34 (2d ed. 2006).” Crawford states,

“The occupation of Iraq in 2003 illustrated the difference between ‘government’ and ‘State’; when Members of the Security Council, after adopting SC res. 1511, 16 October 2003, called for the rapid ‘restoration of Iraq’s sovereignty,’ they did not imply that Iraq had ceased to exist as a State but that normal governmental arrangements should be restored (Id.).”

The Hawaiian Kingdom Civil Code provides, “The laws are obligatory upon all persons, whether subjects of this kingdom, or citizens or subjects of any foreign State, while within the limits of this kingdom, except so far as exception is made by the laws of nations in respect to Ambassadors or others. The property of all such persons, while such property is within the territorial jurisdiction of this kingdom, is also subject to the laws (Hawaiian Kingdom Civil Code, §6 (Compiled Laws 1884).” The Hawaiian Kingdom Penal Code defines treason “to be any plotting or attempt to dethrone or destroy the King, or the adhering to the enemies thereof, giving them aid and comfort, the same being done by a person owing allegiance to this kingdom (Hawaiian Kingdom Penal Code, Chapter VI, sec. 1 (1869).” For any person committing the crime of treason “shall suffer the punishment of death; and all his property shall be confiscated to the government (Id., at sec. 9).”

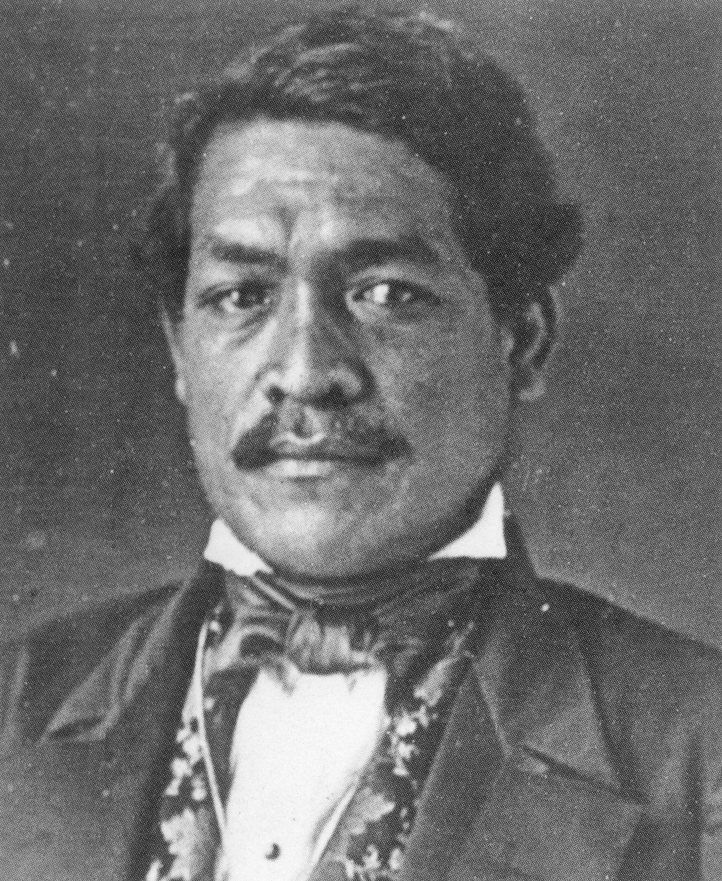

On January 16, 1893, the United States intervened in the internal affairs of the kingdom when its diplomat—Minister John Stevens, ordered the landing of U.S. troops to actively participate in the treasonous take over of the Hawaiian government. The following day, U.S. troops forcibly removed the executive Monarch—Queen Lili’uokalani, and her Cabinet of four ministers, and replaced them with insurgents led by Hawai‘i Supreme Court Judge Sanford Dole. The insurgents’ proclamation of January 17, 1893 stated:

“All officers under the existing Government are hereby requested to continue to exercise their functions and perform the duties of their respective offices, with the exception of the following named person: Queen Liliuokalani, Charles B. Wilson, Marshal, Samuel Parker, Minister of Foreign Affairs, W.H. Cornwell, Minister of Finance, John F. Colburn, Minister of the Interior, Arthur P. Peterson, Attorney-General, who are hereby removed from office. All Hawaiian Laws and Constitutional principles not inconsistent herewith shall continue in force until further order of the Executive and Advisory Councils (Robert C. Lydecker, Roster Legislatures of Hawaii 188 (1918).”

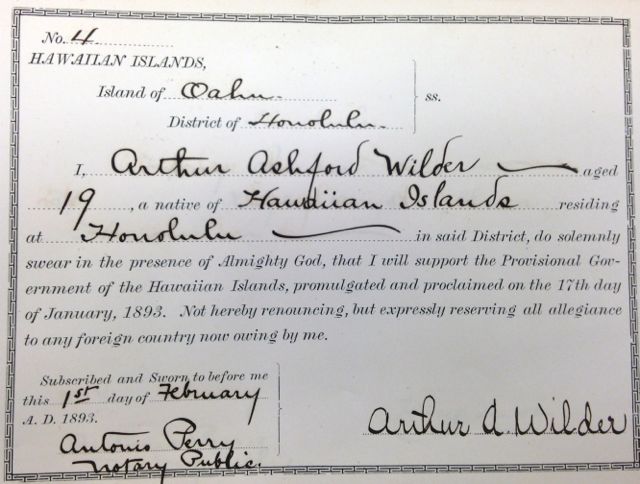

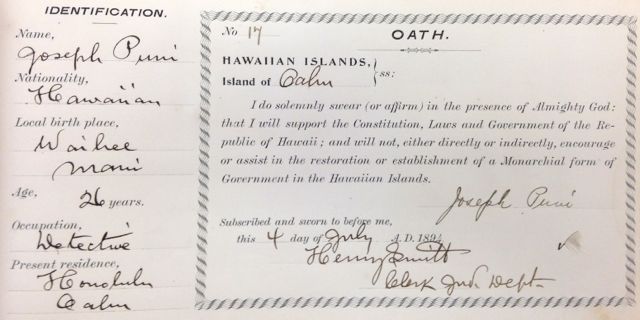

Once the regime change was effected, all government officers and employees were forced to sign oaths of allegiance or face termination or arrest. This being done under the oversight of U.S. troops after Minister Stevens declared Hawai‘i to be an American Protectorate on February 1, 1893. The purpose of the regime change was for the provisional government to cede, by treaty, Hawai‘i’s sovereignty and territory to the United States.

One month after the treaty of annexation was signed in Washington, D.C., on February 14, 1893, under President Benjamin Harrison and submitted to the Senate for ratification, President Grover Cleveland, Harrison’s successor, withdrew the treaty and initiated an investigation into the overthrow of the Hawaiian Government. President Cleveland concluded that the provisional government was neither de facto nor de jure, but self-declared (United States House of Representatives, 53d Cong., Executive Documents on Affairs in Hawai‘i: 1894-95, 453 (Government Printing Office 1895), and the U.S. “military demonstration upon the soil of Honolulu was itself an act of war (Id., at 451).” The President then notified the Congress that he began executive mediation with the Queen to reinstate her and her Cabinet of ministers on condition she would grant amnesty to the insurgents. The first of several meetings were held at the U.S. Legation in Honolulu on November 13, 1893 (Id., at 1241-43). An agreement was reached on December 18, 1893 (Id., at 1269-73), but President Cleveland was unable to get Congressional authorization for the use of force in order to redeploy the troops to Hawai‘i. The agreement was not carried out. This executive agreement is recognized under international law as a treaty.

On July 4, 1894, the insurgency declared the Provisional Government to be the Republic of Hawai‘i and continued to have government officers and employees sign oaths of allegiance under threat by American mercenaries who were employed by the insurgency. The proclamation of the insurgents stated,

“it is hereby declared, enacted and proclaimed by the Executive and Advisory Councils of the Provisional Government and by the elected Delegates, constituting said Constitutional Convention, that on and after the Fourth day of July, A.D. 1894, the said Constitution shall be the Constitution of the Republic of Hawaii and the Supreme Law of the Hawaiian Islands (Lydecker, at 225).”

On June 17, 1897, the day after a second treaty of annexation was signed in Washington, D.C., under President William McKinley, Cleveland’s successor; Queen Lili‘uokalani submitted a formal protest to the U.S. State Department. Her protest stated,

On June 17, 1897, the day after a second treaty of annexation was signed in Washington, D.C., under President William McKinley, Cleveland’s successor; Queen Lili‘uokalani submitted a formal protest to the U.S. State Department. Her protest stated,

“I declare such a treaty to be an act of wrong toward the native and part-native people of Hawaii, an invasion of the rights of the ruling chiefs, in violation of international rights both toward my people and toward friendly nations with whom they have made treaties, the perpetuation of the fraud whereby the constitutional government was overthrown, and, finally, an act of gross injustice to me.”

President McKinley ignored the protest and submitted the treaty to the Senate for ratification. Additional protests were filed with the Senate from the people, which included a 21,269 signature-petition of members and supporters of the Hawaiian Patriotic League protesting the annexation of Hawai‘i. By March of 1898, the treaty is dead after the Senate was unable to garner enough votes for ratification.

Keokani Marciel is a lifelong aloha ʻāina (Hawaiian patriot) and kanaka ʻōiwi (aboriginal Hawaiian) who holds a B.S. in Nutrition Science from the University of California at Davis, and an M.S. in Exercise Science from California University of Pennsylvania. In 2008, Keokani made a career change to mathematics education, and is now beginning an actuarial career. With his background, he brings a quantitative and scientific outlook to the discourse regarding the legal status of Hawaiʻi as an occupied nation-state.

Keokani Marciel is a lifelong aloha ʻāina (Hawaiian patriot) and kanaka ʻōiwi (aboriginal Hawaiian) who holds a B.S. in Nutrition Science from the University of California at Davis, and an M.S. in Exercise Science from California University of Pennsylvania. In 2008, Keokani made a career change to mathematics education, and is now beginning an actuarial career. With his background, he brings a quantitative and scientific outlook to the discourse regarding the legal status of Hawaiʻi as an occupied nation-state.